Abstract

Homogalacturonan (HG), a component of pectin, is synthesized in the Golgi apparatus in its fully methylesterified form. It is then secreted into the apoplast where it is typically de-methylesterified by pectin methylesterases (PME). Secretion and de-esterification are critical for normal pectin function, yet the underlying transcriptional regulation mechanisms remain largely unknown. Here, we uncovered a mechanism that fine-tunes the degree of HG de-methylesterification (DM) in the mucilage that surrounds Arabidopsis thaliana seeds. We demonstrate that the APETALA2/ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR (AP2/ERF) transcription factor (TF) ERF4 is a transcriptional repressor that positively regulates HG DM. ERF4 expression is confined to epidermal cells in the early stages of seed coat development. The adhesiveness of the erf4 mutant mucilage was decreased as a result of an increased DM caused by a decrease in PME activity. Molecular and genetic analyses revealed that ERF4 positively regulates HG DM by suppressing the expression of three PME INHIBITOR genes (PMEIs) and SUBTILISIN-LIKE SERINE PROTEASE 1.7 (SBT1.7). ERF4 shares common targets with the TF MYB52, which also regulates pectin DM. Nevertheless, the erf4-2 myb52 double mutant seeds have a wild-type mucilage phenotype. We provide evidence that ERF4 and MYB52 regulate downstream gene expression in an opposite manner by antagonizing each other’s DNA-binding ability through a physical interaction. Together, our findings reveal that pectin DM in the seed coat is fine-tuned by an ERF4–MYB52 transcriptional complex.

The ERF4–MYB52 transcriptional complex fine-tunes the degree of homogalacturonan de-methylesterification in the seed coat to regulate seed mucilage adherence.

Introduction

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) seed coat mucilage provides a model for studying the molecular mechanisms that control pectin synthesis, secretion, and modification. The mucilage is a specialized extracellular matrix composed predominantly of the pectin rhamnogalacturonan I (RG-I, ∼90%) together with smaller amounts of partially methyl-esterified homogalacturonan (HG) and hemicellulose (Arsovski et al., 2010; Haughn and Western, 2012; Francoz et al., 2015; Šola et al., 2019). In mature Arabidopsis seeds, the dehydrated mucilage is located between the primary wall and the columella, a volcano-shaped secondary wall (Western et al., 2000; Francoz et al., 2015). The mucilage rapidly rehydrates when mature dry seeds imbibe water, which causes the radial primary wall to rupture. The mucilage then expands to form a gelatinous halo that surrounds the seed (Stork et al., 2010; Šola et al., 2019). This halo is composed of an inner, adherent mucilage (AM) layer that is tightly attached to the seed and an outer, non-AM (NM) layer that is readily released when the seeds are suspended in water (Western et al., 2001; Macquet et al., 2007).

Arabidopsis seed mucilage RG-I has a backbone composed of the repeating disaccharide [-4)-α-d-GalpA-(1-2)-α-l-Rhap-(1-] (GalA, galacturonic acid; Rha, rhamnose). Few if any other glycoses or non-carbohydrate substituents are attached to this backbone. The mucilage HG is composed of linear 1,4-linked α-d-GalA residues (Voiniciuc et al., 2015). Some of these GalA residues are methylesterified at their C-6 carboxyl (Ridley et al., 2001; Macquet et al., 2007). Methyl-esterification occurs in the Golgi apparatus, where HG is synthesized. The methylesterified HG is then secreted into the apoplast where it is selectively de-methylesterified by pectin methylesterases (PMEs). The extent of de-methylesterification (DM) may be controlled by PME inhibitors (PMEIs). These proteins are believed to interact directly with PME and thereby inhibit its enzymatic activity (Wolf et al., 2009; Wormit and Usadel, 2018).

The pattern and degree of methylesterification (DM) may have a substantial effect on the biological and physical properties of pectin (Wolf et al., 2009; Peaucelle et al., 2012; Wormit and Usadel, 2018). For example, PMEs that perform blockwise DM generate regions of contiguous GalA residues. Such regions are readily crosslinked by Ca2+ to form the so-called “egg-box” structures (Micheli, 2001). By contrast, PMEs that perform random DM generate HG that does not form extensive crosslinks with Ca2+. These pectins are often susceptible to pectin-degrading enzymes including endopolygalacturonases (Micheli, 2001; Sénéchal et al., 2014; Levesque-Tremblay et al., 2015). Thus, there is considerable interest in understanding the molecular factors that control HG methylesterification status and how this contributes to plant growth and development and to plants’ responses to biotic and abiotic stresses (for review, see Sénéchal et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2018).

Several PMEs and PMEIs have been reported to be involved in the DM of Arabidopsis seed mucilage HG. For example, mutant plants lacking PME58 produce mucilage with a moderate increase in the DM of HG and reduced adherence (Turbant et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2020). By contrast, loss-of-function mutations in two PMEI genes (PMEI6 and PMEI14), SUBTILISIN-LIKE SERINE PROTEASE 1.7 (SBT1.7), and FLYING SAUCER1 (FLY1) result in higher PME activity, a lower DM of HG and an increased mucilage adherence (in pmei14) or a severe mucilage extrusion defect (in pmei6, sbt1.7, and fly1; Rautengarten et al., 2008; Saez-Aguayo et al., 2013; Voiniciuc et al., 2013; Turbant et al., 2016; Shi et al., 2018). Together these studies provide evidence that the DM of HG affects the adherence of the seed mucilage and its extrusion from the seed coat (Šola et al., 2019).

PME and PMEI are encoded by large, multigene families that exist in all land plants (Wang et al., 2013; Wormit and Usadel, 2018). Thus, complex transcriptional networks have likely evolved to fine-tune the tissue location and the extent of pectin methylesterification and de-esterification. To date, only five transcription factors (TFs) involved in the regulation of this process have been identified. It is notable that all five TFs were identified exclusively in studies of Arabidopsis seed coat development (Walker et al., 2011; Ezquer et al., 2016; Shi et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2020). SEEDSTICK (STK) negatively regulates HG DM through direct activation of PMEI6 (Ezquer et al., 2016). MYB52 also negatively regulates pectin DM by directly activating PMEI6, PMEI14, and SBT1.7 (Shi et al., 2018). The seeds of the stk mutant have a severe extrusion defect, whereas myb52 mucilage extrudes normally but the proportion of mucilage in the AM layer is increased compared with those of the wild type. LEUNIG_HOMOLOG/MUCILAGE MODIFIED1 (LUH/MUM1) activates all the direct target genes of STK and MYB52. Nevertheless, PME activity is reduced in the luh mutant and the DM of its seed mucilage HG is increased. The luh seed coat also has a mucilage extrusion defect similar to stk, pmei6, and sbt1.7 seeds (Rautengarten et al., 2008; Huang et al., 2011; Saez-Aguayo et al., 2013).

We recently showed that BEL1-LIKE HOMEODOMAIN2 (BLH2) and BLH4 directly activate the expression of PME58 and thereby redundantly regulate mucilage DM (Xu et al., 2020). BLH2 and BLH4 also repress the expression of STK and MYB52, in contrast to LUH/MUM1, which activates the expression of MYB52 (Shi et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2020). Thus, controlling the DM of HG is likely critical for the adhesion of the mucilage to the seed coat. This adhesion must be maintained for normal mucilage extrusion as both higher and lower DM levels cause extrusion defects. Together these data provide further evidence for the complexity of the regulatory network involved in regulating HG methylesterification (Shi et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2020). Nevertheless, additional studies are required to reveal the fundamental molecular and biochemical mechanisms underlying this process.

Here, we report that HG DM in the Arabidopsis seed coat is positively regulated by the APETALA2/ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR (AP2/ERF) TF ERF4. ERF4 directly represses the expression of PMEI13, 14, 15, and SBT1.7. We provide gene expression and genetic evidence that ERF4 interacts with MYB52 and that this interaction antagonizes each of their transcriptional activities. Thus, ERF4 and MYB52 have opposing roles in HG DM. Based on these results, we have developed a model that depicts a fine-tuned regulatory mechanism in which ERF4 and MYB52 antagonistically regulate pectin DM in the seed coat.

Results

ERF4 is specifically expressed in seed coat epidermal cell

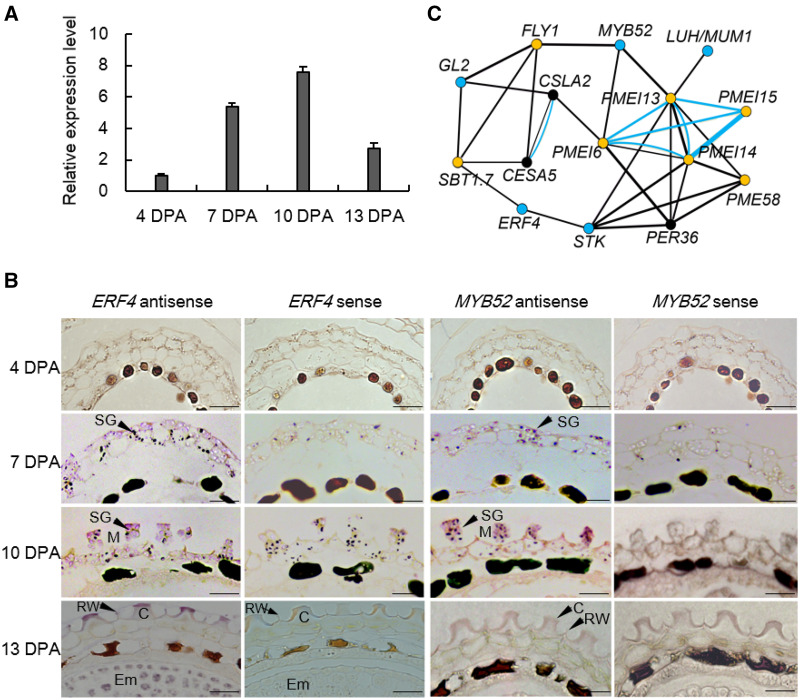

Searches of the Arabidopsis eFP public database indicated that ERF4 is expressed predominantly in developing seeds (Winter et al., 2007; Le et al., 2010; Supplemental Figures S1, S2). We further investigated ERF4 expression in developing siliques at 4 days post-anthesis (DPA) and in seed coats at 7, 10, and 13 DPA (Figure 1, A). ERF4 expression was maintained at its maximum level from 7 DPA to 10 DPA, corresponding to seeds from cotyledon stage to mature cotyledon stage based on our section analysis (Supplemental Figure S3, A), when mucilage production in seed coats is at its peak. At 13 DPA, the expression of ERF4 in seed coats decreased greatly.

Figure 1.

Expression analysis of ERF4 and MYB52. (A) Relative expression level of ERF4 in 4 DPA siliques and 7, 10, and 13 DPA seed coat obtained by qPCR analysis. Gene expression was measured relative to ATACTIN2. Total RNA was extracted from three different batches of siliques or seed coats as biological replicates. Each batch of siliques or seed coats was pooled from more than 50 plants. For each biological replicate, ∼100 siliques of the same batch were collected at 7–10 DPA. Values are mean ± sd of three independent biological replicates. The expression level at 4 DPA was set as 1. (B) In situ hybridization of ERF4 and MYB52 transcripts in the 4, 7, 10, and 13 DPA seed coat. SG, starch granule; M, mucilage; C, columella; RW, radial cell wall. Bars = 50 μm. (C) Co-expression network of ERF4 with genes being involved in mucilage production based on GeneMANIA. GL2, GLABRA2; LUH/MUM1, MUCILAGE-MODIFIED1; MYB52, MYB DOMAIN PROTEIN 52; STK, SEEDSTICK; FLY1, FLYING SAUCER 1; CSLA2, CELLULOSE SYNTHESIS-LIKE A2; CESA5, CELLULOSE SYNTHEASE 5; SBT1.7, SUBTILISIN-LIKE SERINE PROTEASE 1.7; MUCI10, MUCILAGE-RELATED 10; PER36, PEROXIDASE 36; PMEI6, 13, 14, 15, PETIN METHYLESTERASE INHIBITOR 6, 13, 14, 15; PME58, PETIN METHYLESTERASE 58. Nodes for TFs are colored in blue, genes involved in cellulose synthesis are in black and genes involved in mucilage modification are in orange. Co-expression is indicated with black lines. Proteins that share similar domains are linked with blue lines.

We next transformed wild-type plants with a ProERF4:GUS construct to obtain information on the spatial and developmental expression profile of ERF4. GUS expression was discernible in most vegetative and reproductive tissues and organs (Supplemental Figure S4). Strong GUS signals were present in the integument of developing seeds at 7, 10, and 13 DPA (Supplemental Figure S4, J–L). At 10 DPA, GUS activity is mainly present in the seed coat, although at 13 DPA, it was detected in both the seed coat and embryo (Supplemental Figure S4, M and N). Thus, ERF4 is preferentially expressed in the seed coat at early developmental stages.

To examine the specific cell types in which ERF4 is expressed in the seed, we performed in situ hybridization. Our results demonstrate that ERF4 expression is confined to the epidermal cell layer or mucilage secretory cells (MSCs) of the outer integument at 7, 10, and 13 DPA (Figure 1, B). Almost no hybridization signal was discernible in the MSCs at 4 DPA. At 13 DPA, the hybridization signal was also observed in the embryo, which is consistent with our GUS staining data. Taken together, these results confirm that ERF4 is expressed in 7–10 DPA MSCs when seed coat mucilage begins to accumulate (Francoz et al., 2015).

ERF4 is predicted by Cytoscape v3.7.1 with GeneMANIA (Warde-Farley et al., 2010) to be co-expressed with multiple mucilage-related genes including the TFs STK, LUH/MUM1, MYB52, and GLABRA2 (GL2), and the DM-modifiers PMEI6, PMEI14, PME58, SBT1.7, and FLY1 (Figure 1, C). The co-expression of ERF4 and MYB52 in the seed coat was confirmed by an in situ hybridization assay (Figure 1, B). Collectively, the expression pattern and co-expression network of ERF4 led us to suspect that it has a role in seed mucilage modification.

Mucilage adhesiveness is reduced in erf4 seeds

Two independent homozygous T-DNA insertion lines, erf4-1 (SALK_200761) and erf4-2 (SALK_073394), were obtained (Supplemental Figure S5, A). The expression of ERF4 in these mutants was examined by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using RNA extracts from developing seeds. No amplification was obtained with erf4-1 using primers located at the 5′-side of the erf4-1 insertion. A discernible amplification was observed in erf4-2 for its 5′-side region (Supplemental Figure S5, B). No full-length transcript was recreated by splicing out the T-DNA insertion when amplification was performed with primers encompassing the entire ERF4 coding sequence (CDS). Together, these results indicate that erf4-1 and erf4-2 homozygotes do not produce the wild-type ERF4 transcript.

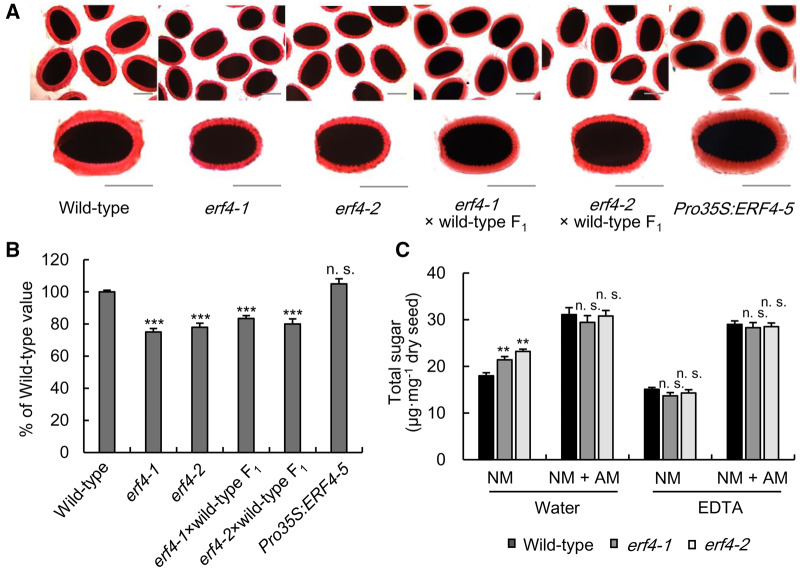

Mature erf4 seeds were stained with ruthenium red (RR) to determine if ERF4 has a role in seed mucilage production and morphology (Western et al., 2000). Wild-type and erf4 mucilage had similar morphologies when the seeds were suspended in deionized water and shaken moderately (Supplemental Figure S5, C and D). However, the erf4 seeds had a thinner mucilage halo and the thickness of the AM was reduced by ∼30% compared with wild type when the seeds were shaken for 2 h at 200 rpm (Figure 2, A and B). The reduced AM phenotype was complemented by transforming erf4-2 with Pro35S:ERF4, suggesting it likely results from a loss-of-function mutation in ERF4 (Supplemental Figure S5, E and F).

Figure 2.

Mucilage-related phenotypes of erf4 seeds. (A) RR staining of AM of wild type, erf4, F1 progeny of the cross between erf4 and wild type, and Pro35S:ERF4 seeds. Mature dry seeds were shaken for 2 h at 200 rpm in deionized water containing 0.01% (w/v) RR before being photographed with an optical microscope. Bars = 200 μm. (B) Thickness of the AM layers. Measurements were made from the top to the bottom of the red halo across the short axis. Data represent average thickness ± sd from three independent biological replicates. For each biological replicate, more than 20 seeds were measured. The average thickness of wild-type seeds was set to 100%. n.s., not significant; ***, P < 0.001; Student’s t test. (C) Comparison of total sugar amounts in the NM and AM layers of wild-type and erf4 seeds shaken for 2 h at 200 rpm in water or 50 mM EDTA (pH 8.0). Total sugars were extracted from three different batches of dry seeds (∼5 mg) as biological replicates. Each batch of seeds was pooled from more than 50 plants. Values represent means ± sd of three independent biological replicates. **, P < 0.01; Student’s t test.

We next sectioned seeds at 4, 7, 10, and 13 DPA and then stained them with toluidine blue O, a metachromatic dye that colors mucilage pink (Western et al., 2000) to determine if eliminating ERF4 affects mucilage deposition. Our data show that the shape of the MSCs is similar in erf4-2 and wild type, and that the deposition of mucilage was unaffected (Supplemental Figure S3, B). Even though erf4 seed coat morphology is visibly unaltered, its AM layer is more readily extracted with water than wild type suggesting that the mucilage is somewhat less tightly bound. This led us to suspect that mutating ERF4 affected pectin structure and organization.

Mucilage re-partitioning between NM and AM occurred in erf4 seeds

We have shown that the erf4 AM layer has a reduced thickness than wild-type seeds. To examine whether the distribution of mucilage was affected, we sequentially extracted the NM and AM layers from mature erf4 and wild-type seeds (Supplemental Figure S6, A and B) and analyzed their sugar contents. Rha and GalA (molar ratio ∼1) were the predominant monosaccharides detected in the NM and AM layers of wild-type and erf4 mucilage (Supplemental Table S1). Small amounts of mannose, galactose, and xylose were also detected. The amounts of mucilage sugars in the combined AM and NM layers were similar in erf4 and wild-type seeds. However, the amounts of mucilage sugars were reduced to 64% and 57% of wild type in the AM layer of erf4-1 and erf4-2, respectively. Conversely, in the NM layer of erf4-1 and erf4-2, mucilage sugars were 14% and 28% more abundant than in the wild type, respectively, (Figure 2, C and Supplemental Table S1). These results suggest that loss-of-function mutations in ERF4 do not affect the total amounts of mucilage formed. Rather, they lead to reduction in mucilage adhesiveness, which in turn increases the abundance of pectin in the NM layer.

The divalent cation chelator EDTA would be expected to disrupt ionic cross links between HG chains and thus alter the ability of the AM layer to adhere to the seed coat (Voiniciuc et al., 2013; Ezquer et al., 2016; Turbant et al., 2016). Our previous study showed that EDTA extracts more mucilage sugars from the myb52 seeds than water (Shi et al., 2018). In this study, EDTA extracts slightly less polysaccharides than water for both wild-type and erf4 seeds (Figure 2, C and Supplemental Figures S6, S7). Thus, in contrast to myb52, the seed coat mucilage of erf4 is sensitive to water extraction, but not to EDTA extraction.

For comparison, we also stained EDTA treated myb52, erf4-2 myb52, fly1, pme58, and blh2 blh4 seeds with 0.01% RR. For wild type and all the mutants studied, either EDTA at pH 6.0 or 8.0 treatment increased the halo thickness compared with water treatment, suggesting that EDTA treatment causes the pectin structure to swell (Supplemental Figure S7, A and B). Similar results were also obtained by treating the seeds with Na2CO3 (pH 11.0; Supplemental Figure S7, A and B).

ERF4 mutation affects DM of HG in seed coat mucilage

Previous studies have established that the physical properties of mucilage are affected by its DM, which in turn can alter mucilage extrusion and partitioning between the AM and NM layers (Ezquer et al., 2016; Šola et al., 2019). Our co-expression data showed that ERF4 is co-expressed with a group of PME-related genes (Figure 1, C). To determine if DM is altered in the erf4 seed mucilage, we measured DM indirectly by quantifying the amounts of formaldehyde produced from the released methanol by alcohol oxidase. DM was increased by ∼10% and ∼19% in erf4-1 and erf4-2, respectively, compared with wild type (Figure 3, A).

Figure 3.

Mucilage DM and localization in erf4 seeds. (A) Degree of HG methylesterification (DM%) of whole seed mucilage. Total mucilage was extracted from three different batches of dry seeds as biological replicates. For each biological replicate, about 20-mg seeds of the same batch was extracted with 400 μL water using ultrasonic extraction. Error bars represent sd values from three independent biological replicates. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; n.s., not significant; Student’s t test. (B) Immunolabeling of AM layer of seeds. Optical sections of AM were visualized by confocal microscopy. HGs with no methylesterification, low methylesterification, and high methylesterification are recognized by CCRC-M38, JIM7, and JIM5, respectively. Bars = 50 μm.

To obtain additional evidence that ERF4 affects HG DM, we used monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that recognize highly methylesterified HGs (JIM7), poorly methylesterified HGs (JIM5), and non-methylesterified HGs (CCRC-M38) to immunolabel wild-type and erf4 seeds (Willats et al., 2001b; Macquet et al., 2007). JIM7 labeling was observed throughout the AM layer of wild-type seeds (Macquet et al., 2007), with labeling substantially increased in erf4-1 and erf4-2 (Figure 3, B and Supplemental Figure S8). In contrast, the intensity of JIM5 and CCRC-38 labeling was lower along the ray structures of erf4 when compared with wild type (Figure 3, B and Supplemental Figures S9, S10). Taken together, our results suggest that in the seed coat ERF4 may have a role in promoting HG DM.

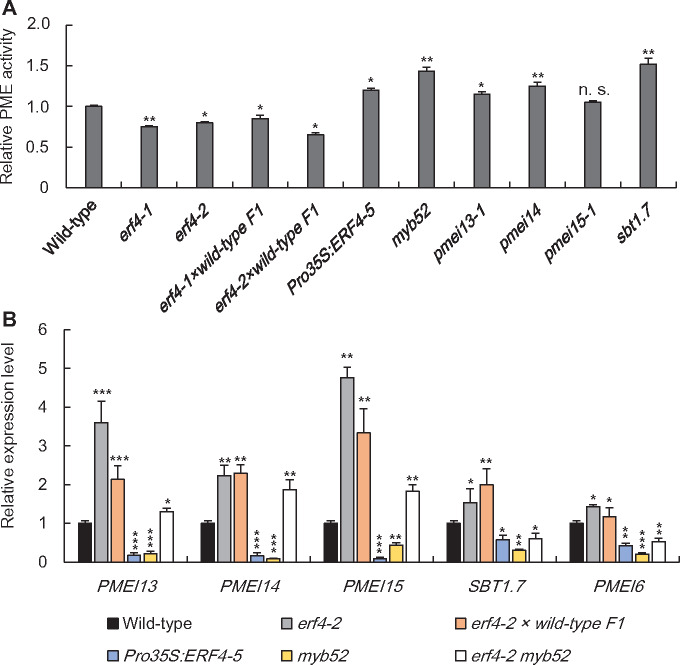

PME activity is decreased in erf4 seed coat

To determine if the increased DM of erf4 seed mucilage was a result of decreased PME activity, we measured PME activity in total proteins extracted from 7 to 10 DPA seed coats of wild-type and erf4 mutants as well as erf4-2:Pro35S:ERF4 and Pro35S:ERF4 overexpressors. PME activity in erf4 was reduced to 70%–80% of wild type, whereas it was greater in Pro35S:ERF4 (Figure 4, A). PME activity in three independent erf4-2:Pro35S:ERF4 transformed lines was similar to wild type (Supplemental Figure S5, G). Collectively, our results demonstrate that eliminating ERF4 results in a discernible decrease in PME activity and an increase in DM, indicating that in the seed coat ERF4 positively regulates mucilage DM.

Figure 4.

PME activity in selected mutants and PME-related genes that are modulated by ERF4 and MYB52. (A) PME activities were determined in total protein extracts from the developing seed coat at 7–10 DPA. The relative PME activity was measured using a gel diffusion assay and is normalized to the average wild-type activity (=1). Total protein was extracted from three different batches of seed coats as biological replicates. Each batch of seed coats was pooled from ∼100 siliques from more than 50 plants. Values are means ±sd from three independent biological replicates. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; n.s., not significant; Student’s t test. (B) Expression patterns of PMEI13, PMEI14, PMEI15, PMEI6, and SBT1.7 in 7–10 DPA seed coats of mutant seeds, including erf4-2, myb52, F1 progeny (erf4-2 × wild-type), Pro35S:ERF4, and erf4-2 myb52, compared with the wild type. Gene expressions are shown relative to ATACTIN2. Total RNA was extracted from three different batches of seed coats as biological replicates. Each batch of seed coats was pooled from ∼100 siliques from more than 50 plants at 7–10 DPA. Two technical replicates were performed for each biological replicate. Values are means ± sd of three independent biological replicates. The expression level for each gene in wild type was set as 1. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; Student’s t test.

The erf4 mucilage phenotype results from a loss of function of ERF4 in the seed coat rather than the embryo

A previous study showed that the mucilage extrusion defect in hms seeds is caused by a loss-of-function mutation in HMS in the embryo rather than in the seed coat (Levesque-Tremblay et al., 2015). To assess if the erf4 mucilage phenotype was caused by the genotype of the seed coat, the embryo, or both, we crossed erf4-1 and erf4-2 (female parent) with wild type (male parent) to obtain F1 seeds. The seed coat cells are homozygous whereas the embryo is heterozygous for the ERF4 mutation. The F1 and erf4 seeds had similar mucilage adhesiveness, DM, and PME activity (Figures 2, A and B, 3, A, and 4, A). Thus, the erf4 mucilage phenotype results from a loss of ERF4 function in the seed coat and is independent of its function in embryo development. We also analyzed the seed mucilage phenotype of the F2 progenies and found that genetic segregation for both populations is consistent with the Mendelian inheritance of a single recessive nuclear mutation (Supplemental Table S2).

The erf4 mucilage defect is associated with decreased cross-linking of mucilage by calcium

Lowering the DM of HG is known to facilitate the formation of calcium-mediated cross links between HG chains and thereby increase the stiffness of the mucilage gel matrix (Ezquer et al., 2016). To investigate if the increased DM in erf4 affects Ca2+ cross linking, we immunolabeled seed coat mucilage with 2F4, a mAb that recognizes regions of HG crosslinked by Ca2+ (Liners et al., 1989). 2F4 labeling intensity was reduced in erf4-2 seeds compared with the wild type (Supplemental Figure S11), suggesting that there are fewer Ca2+ crosslinked HGs in erf4 mucilage than in the wild type. Thus, decreased calcium-mediated cross-links between HGs may contribute to the reduced cohesiveness seed coat mucilage phenotype observed in erf4. It has been reported that treating wild-type and fly1 seeds with aqueous CaCl2 results in a more compact mucilage halo (Voiniciuc et al., 2013). We treated erf4 seeds with aqueous CaCl2 and found that the mucilage halo of wild type and erf4 was more condensed compared with water treated seeds (Supplemental Figure S7, A and B). A similar effect was also observed with myb52, erf4 myb52, fly1, pme58, and blh2 blh4 seeds (Supplemental Figure S7, A and B).

ERF4 regulates the expression of PME-related genes

To investigate how ERF4 positively regulates HG DM in the seed coat, we performed whole transcriptome RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) with wild type and erf4-2 developing seeds at 7 DPA. A total of 2,668 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified in erf4-2 compared with the wild type. In total, 1,356 genes were upregulated and 1,312 downregulated (Supplemental Figure S12, A and B and Supplemental Data Set S1). Since ERF4 was previously reported to be a transcription repressor (Fujimoto et al., 2000), we focused our efforts on the upregulated DEGs in erf4. Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis indicates that the 1,356 upregulated DEGs are involved in cellular component organization or biogenesis, developmental processes, cellular processes, and metabolic processes (Supplemental Figure S12, C). Furthermore, we identified 125 upregulated genes including 10 PMEI genes and SBT1.7 that were annotated with cellular component of extracellular region, i.e. the plant cell wall, which is consistent with the ERF4 function in HG modification.

We verified the accuracy of the transcriptomic data by examining the expression of selected DEGs by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) using RNA extracts from 7 to 10 DPA seed coats from wild-type, erf4-2 and Pro35S:ERF4 plants. The expression of SBT1.7 and all 10 PMEIs, including AT1G09370, AT1G56100 (PMEI14), AT1G70720, AT3G05741, AT3G17130, AT4G00872, AT4G15750 (PMEI13), AT5G20740, AT5G50060, and AT5G62350, was downregulated in seeds overexpressing ERF4 but upregulated in erf4 compared with the wild type (Figure 4, B and Supplemental Figure S12, D). According to our RNA-seq data, all DM-modifying genes except SBT1.7, i.e. LUH/MUM1, STK, MYB52, BLH2, BLH4, FLY1, PME58, and UDP-URONIC ACID TRANSPORTER1 (UUAT1), are not regulated by ERF4. Our qPCR analyses validate these data except that we found PMEI6 could also be a potential target of ERF4 (Figure 4, B and Supplemental Figure S13).

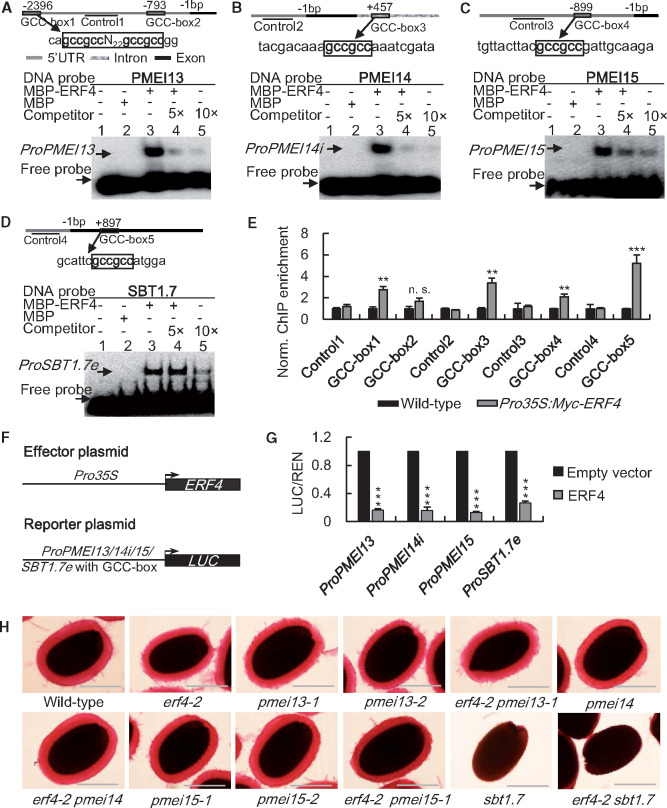

ERF4 binds the GCC-box motifs in PMEI13, 14, 15, and SBT1.7

Previous studies established that Group VIII ERF TFs bind to the cis-acting element of the GCC-box motif (GCCGCC) in regulating downstream target genes (Fujimoto et al., 2000). Cis-acting elements are typically located in the promoter region. However, cis-elements that are located in the region of an intron or an exon have also been reported (de Vooght et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2015). We analyzed the genomic sequences of SBT1.7 and PMEI6 and the 10 PMEI genes that are regulated by ERF4 and found that SBT1.7, PMEI13, PMEI14, and AT3G05741 (referred to as PMEI15 hereafter) have GCC-box motifs in their promoter, intron or exon regions (Figure 5, A–D and Supplemental Data Set S2). Thus, they may be direct targets of ERF4. In contrast, PMEI6 may be indirectly regulated by ERF4 as no GCC-box binding site was identified.

Figure 5.

ERF4 regulates PME activity in the seed coat by directly modulating the expression of PMEI13, 14, 15, and SBT1.7. (A)–(D) EMSA showing that ERF4 binds to DNA fragments containing the GCC-box motif. The GCC-box motifs were located in the promoters of PMEI13 (A) and PMEI15 (C), intron of PMEI14 (B), and exon of SBT1.7 (D). Relative nucleotide positions of the putative ERF binding site are indicated (with the first base preceding the ATG start codon designated −1). The DNA probes were 5′-biotin-labeled fragments containing the GCC-box motif. Competitors were the same fragments but were non-labeled (5- and 10-fold that of the hot DNA probe). The MBP-tagged ERF4 fusion protein (MBP–ERF4) was purified. The MBP tag alone was used as negative control. The sequences show the GCC-box motif which is highlighted in bold. (E) ChIP-qPCR analysis of chromatin extracts from transgenic plants expressing the Myc-ERF4 fusion protein and wild type. Three different batches of developing seeds of wild type and Pro35S:Myc-ERF4 were pooled from more than 50 plants as biological replicates. Nuclei from each batch of seeds were immunoprecipitated with an anti-Myc antibody. The precipitated chromatin fragments from each replicate were then analyzed by qPCR with primers amplifying the GCC-box containing regions (GCC-box1, -box2, -box3, -box4, and -box5) with the promoter region without GCC-box as negative control as indicated in (A)–(D). Data represent means ± sd from three independent biological replicates using different batches of developing seeds. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; Student’s t test. (F) Vectors used in the dual-LUC transient transcriptional activity assays. Expression of ERF4 and the REN internal control was driven by the CaMV 35S promoter. The LUC reporter gene was driven by genomic sequences from the promoters of PMEI13 or PMEI15, first intron of PMEI14 (PMEI14i) or exon of SBT1.7 (SBT1.7e) containing GCC-box motif (ProPMEI13, ProPMEI14i, ProPMEI15, or ProSBT1.7e:LUC). (G) Relative LUC activity demonstrates that ERF4 suppresses the expression of PMEI13, PMEI14, PMEI15, and SBT1.7. Dual-LUC transient transcriptional activity assays were performed in wild-type Arabidopsis protoplasts. LUC/REN represents the relative activity of promoters. Data represent the means ± sd from three independent biological replicates. ***, P < 0.001, Student’s t test. (H) RR staining showed genetic interactions between ERF4 and its downstream target genes. For mucilage extrusion analysis, mature dry seeds were shaken for 2 h at 200 rpm in deionized water containing 0.01% RR. Bars = 200 μm.

We next used an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) to assess the ability of ERF4 to bind to 5′-biotin labeled probes containing the GCC-box motif in vitro. The purified maltose binding protein (MBP)-ERF4 fusion protein bound to the GCC-box containing fragments of both PMEI13, 14, 15, and SBT1.7 (Figure 5, A–D).

To assess whether ERF4 binds to the GCC-box motifs in vivo, we conducted chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-qPCR assays with chromatin extracts from developing seeds of wild-type plants and plants overexpressing Myc-tagged ERF4 (Pro35S:Myc-ERF4). The presence of ERF4 substantially enhanced detection of the GCC-box containing sequences in the promoters of PMEI13 and PMEI15, intron of PMEI14 (PMEI14i), and exon of SBT1.7 (SBT1.7e), indicating that ERF4 bound to these sequences in planta (Figure 5, E).

Finally, we evaluated the transcriptional regulation of these targets of ERF4 by detecting relative luciferase (LUC) activity in wild-type Arabidopsis protoplasts, with Renilla luciferase (REN) used as an internal control, using the effector plasmid Pro35S:ERF4 and reporter plasmids ProPMEI13, 14i, 15, and SBT1.7e:LUC (Figure 5, F). When Pro35S:ERF4 was co-transformed with either reporter plasmid, LUC activity significantly decreased (Figure 5, G). To verify the notion that ERF4 suppresses SBT1.7 expression by binding to the GCC-box motif in its exon region, we co-transformed the protoplasts with Pro35S:ERF4 and PromuSBT1.7e with a mutated GCC-box and observed that the mutation abolished this binding (Supplemental Figure S14). Together, these results indicate that ERF4 represses the expression of PMEI13, 14, 15, and SBT1.7 by directly binding to the regulatory elements in their promoter, intron, or exon regions.

Role of ERF4 in DM modification is mediated by PMEI13, 14, 15, and SBT1.7

PMEI13, 14, 15, and SBT1.7 are all predominantly expressed in developing seeds at either 4 or 7 DPA and are rarely if ever expressed in the embryo (Supplemental Figures S1, S2, S15), suggesting that their roles are restricted to the seed coat. Indeed, the roles of PMEI14 and SBT1.7 in seed mucilage maturation have been well documented (Rautengarten et al., 2008; Shi et al., 2018). To determine if PMEI13 and PMEI15 have similar functions, we obtained two homozygous T-DNA insertion lines for pmei13 and for pmei15 (Supplemental Figure S16, A). RT-PCR analysis confirmed that all four lines are null mutants (Supplemental Figure S16, B).

RR staining of vigorously shaken pmei13-1 and pmei13-2 seeds showed that their AM layers are thinner than wild type (Figure 5, H). However, the thickness of the mucilage halos for pmei15-1 and pmei15-2 seeds was not significantly different from wild type (Supplemental Figure S17, A). The DM of pmei13-1 seed mucilage was significantly lower than wild type (Figure 4, A and Supplemental Figure S17, B), a result consistent with a substantial increase in PME activity in this mutant (Supplemental Figure S17, C). By contrast, the mucilage DM and the PME activity of pmei15-1 seeds were similar to wild type. This suggests that PMEI13 represses PME activity in seed coat mucilage, whereas PMEI15 has little if any role in seed mucilage modification.

To obtain genetic evidence that ERF4 modulates DM by regulating PMEI13, 14, 15, or SBT1.7, we generated a series of double mutants (erf4-2 pmei13-1, erf4-2 pmei14, erf4-2 pmei15-1, and erf4-2 sbt1.7). erf4-2 sbt1.7 seeds had a mucilage extrusion phenotype and PME activity similar to the sbt1.7 single mutant. However, the double mutant seeds had a mucilage DM that was between erf4-2 and sbt1.7, but was still significantly decreased compared with wild type (Supplemental Figure S17, B). The DM of erf4-2 pmei13-1 and erf4-2 pmei14 double mutant seed mucilage was partially restored to wild-type level compared with erf4-2. Mutating pmei13-1 and pmei14, but not pmei15-1, partially rescued the mucilage phenotype and the reduction of PME activity in erf4-2 seeds (Figure 5, H and Supplemental Figure S17, C). Such a result is consistent with our finding that PMEI13, 14, and 15 are downstream targets of ERF4 with enhanced expression in the erf4-2 seed coat.

ERF4 physically interacts with MYB52

Our previous study has provided evidence that MYB52 directly activates the expression of PMEI6, 14, and SBT1.7 (Shi et al., 2018). In this work, we have provided evidence that ERF4 directly suppresses the expression of PMEI14 and SBT1.7. Therefore, MYB52 and ERF4 have common targets but regulate their expression in opposite ways. Moreover, our in situ hybridization revealed that both ERF4 and MYB52 are predominantly expressed in the seed coat at 7–10 DPA (Figure 1, B). These findings led us to explore the relationships between ERF4 and MYB52. To this end, we performed qPCR to determine if the expression levels of ERF4 and MYB52 differ in myb52 and erf4-2 seeds from that in the wild type, respectively. Our results showed that MYB52 expression in erf4-2 did not change (Supplemental Figure S13), whereas ERF4 expression was increased in myb52 (Supplemental Figure S18). Although the ERF4 promoter contains three MYB binding sites (MBS), our EMSA and ChIP assays showed that MYB52 does not bind to the ERF4 promoter. Thus, MYB52 may indirectly suppress the expression of ERF4, while ERF4 does not regulate MYB52 at the transcriptional level.

To extend our knowledge of the interaction between ERF4 and MYB52 we used a yeast two hybrid (Y2H) assay. Our results show that in this system ERF4 without its EAR motif interacts with MYB52 (Figure 6, A). A pull-down assay confirmed this interaction. When glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged MYB52 (GST-MYB52) was reacted with the purified MBP-ERF4 fusion protein, GST-MYB52 was pulled down by the anti-MBP antibodies (Figure 6, B). No band was detected by immunoblotting when pull-down involved the GST tag alone, suggesting that the interaction between ERF4 and MYB52 is specific.

Figure 6.

ERF4 physically interacts with MYB52. (A) DNA-BDs are required for ERF4–MYB52 interaction. In Y2H experiments, MYB52 was divided into two fragments and their interactions with ERF4 either with or without its EAR repression domain (-EAR) were analyzed. The MYB52 whole length and truncated fragments were ligated into the BD vector, and ERF4/ERF4(-EAR) into the AD vector. ERF4(-EAR) was divided into three fragments and their interactions with the MYB52 N-terminus analyzed. DDO, SD medium lacking Trp and Leu; QDO, SD medium lacking Trp, Leu, His and Ade. The AD and BD vectors were used as negative control. (B) Pull-down assay of ERF4 interaction with MYB52. GST-tagged MYB52 fusion protein (GST–MYB52) or GST alone were incubated with MBP-tagged ERF4 fusion protein (MBP–ERF4) in Sepharose 4B beads. MBP–ERF4 but not MBP was pulled down by beads containing GST–MYB52. MBP tag alone incubated with GST–MYB52 was used as negative control. (C) In vivo co-IP assay of ERF4 and MYB52 interaction. ERF4-Flag MYB52-Myc was overexpressed in Arabidopsis protoplasts. A Flag antibody was used for immunoprecipitation analysis and a Myc antibody was used for immunoblot analysis. The band detected by the Myc antibody in the precipitated protein sample indicates that a physical association between ERF4 and MYB52 occurred. (D) Interaction of ERF4 and MYB52 in Arabidopsis protoplast. Representative cells were imaged by confocal laser scanning microscopy. YFP fluorescence was only detected in Arabidopsis protoplasts producing a ERF4-YC and YN-MYB52 interaction. DAPI, nucleus labeled by DAPI in blue fluorescence; CHI auto-fluorescence in red signal; DIC, bright field. Bars = 10 μm.

We next determined if ERF4 and MYB52 interact in vivo. A co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) assay was performed using Arabidopsis protoplasts transformed with Pro35S:MYB52-Myc and with Pro35S:ERF4-Flag constructs. Total protein was then extracted from the cells and immunoprecipitated with an anti-FLAG antibody. MYB52-MYC was identified in the precipitate using an anti-MYC antibody, which indicates that ERF4 and MYB52 interact in plant cells (Figure 6, C).

To further validate the interaction between ERF4 and MYB52 in planta, we conducted a bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assay using Arabidopsis protoplasts (Figure 6, D). ERF4-YC and YN-MYB52 co-expression gave YFP fluorescence in the nucleus. In contrast, co-expression of ERF4-YC with the YFP N-terminus, the YFP C-terminus with YN-MYB52, or the YFP C-terminus and N-terminus alone did not generate a discernible fluorescence signal.

The DNA-binding domains (BDs) AP2/ERF and Myb are located in the N-terminal regions of ERF4 and MYB52, respectively. Transcriptional repression/activation domains (ADs) are likely located in the C-terminal region. We used a Y2H assay to gain insight into how these domains may interact. Only the N-terminal portion of MYB52 (amino acids [aa] 1–106), which contains the Myb domain, interacted with ERF4. We then generated three fragments of ERF4: the N-terminus (aa 1–23); the AP2/ERF domain (aa 24–87), and the C-terminus (aa 88–222). The N-terminal portion of MYB52 only interacted with the AP2/ERF domain of ERF4 (Figure 6, A). Moreover, when incomplete DNA-BDs were assayed, the interaction between MYB52 and ERF4 was abolished (Supplemental Figure S19). Our results indicate that intact DNA-BDs are required for the interaction between MYB52 and ERF4.

ERF4 and MYB52 antagonize each other’s activity in regulating genes controlling pectin DM

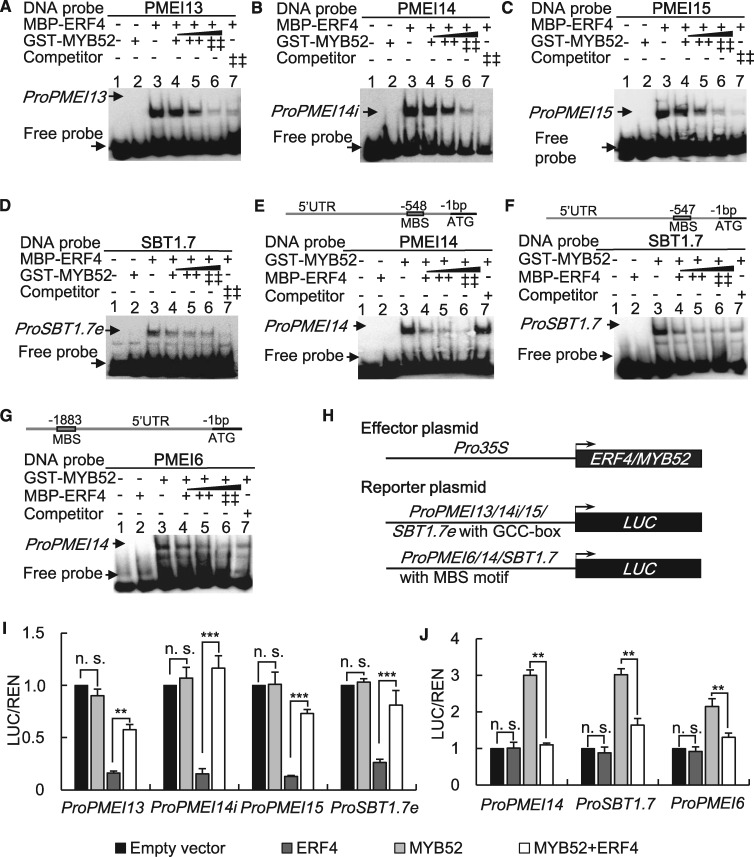

We used EMSAs to determine if the interaction between ERF4 and MYB52 affects the binding of ERF4 to PMEI13, 14, 15, and SBT1.7. To this end, purified MBP-ERF4 and GST-MYB52 fusion proteins were reacted with biotin-labeled probes that contain the GCC-box motif. ERF4 bound to the GCC-box probes (Figure 7, A–D, lane 3), while MYB52 did not (Figure 7, A–D, lane 2). The binding of ERF4 to these probes was gradually diminished when increasing amounts of MYB52 were added (Figure 7, A–D, lanes 4–6). An EMSA using probes containing MBS motifs showed that the ability of MYB52 to bind to PMEI6, 14, and SBT1.7 was gradually weakened when the amounts of ERF4 were increased (Figure 7, E–G). These findings suggest that ERF4 and MYB52 antagonize each other’s activities in a dose-dependent manner.

Figure 7.

MYB52 and ERF4 interfere with each other’s function in modulating the expression of downstream targets. (A)–(D) EMSA showing that MYB52 interferes with the DNA binding ability of ERF4. ERF4 (lane 3) binds to probes containing GCC-box motifs from PMEI13 (A), PMEI14 (B), PMEI15 (C), and SBT1.7 (D), whereas MYB52 (lane 2) did not bind to those motifs. MYB52 interferes with the binding of ERF4 to these promoters (lanes 4–6). The DNA probes were 5′-biotin-labeled fragments containing the GCC-box motif. Competitors were the same fragments but were non-labeled. MBP-ERF4 and GST-MYB52 fusion proteins were purified. (E)–(G) EMSA showing that ERF4 interferes with the DNA binding ability of MYB52. ERF4 (lane 2) did not bind to the MBS motifs in the PMEI14 (E), PMEI6 (F), and SBT1.7 (G) promoters, but MYB52 (lane 3) did bind to them. Increasing the amounts of ERF4 weakened the binding of MYB52 to these promoters (lanes 4–6). Relative nucleotide positions of MBS are indicated (with the first base preceding the ATG start codon designated as −1). The DNA probes were 5′-biotin-labeled fragments containing the MBS motif. Competitors were the same fragments but were non-labeled. (H) Vectors used in the dual-LUC transient transcriptional activity assays. Expression of ERF4 and MYB52 as well as the REN internal control was driven by the CaMV 35S promoter. The LUC reporter gene was driven by promoters of PMEI13 or PMEI15, first intron of PMEI14 (PMEI14i) or exon of SBT1.7 (SBT1.7e) containing the GCC-box motif (ProPMEI13, ProPMEI14i, ProPMEI15, or ProSBT1.7e:LUC) or promoters of PMEI6, 14, or SBT1.7 containing the MBS motif (ProPMEI6, ProPMEI14, or ProSBT1.7:LUC). (I) LUC/REN showed that ERF4 suppression of the PMEI13, 14, 15, and SBT1.7 promoters was inhibited by MYB52. Expression of REN was used as an internal control. LUC/REN represents the relative activity of promoters. For each co-transformation, three biological replicates were performed. Data represent means ± sd of three biological replicates from different co-transformations. n.s., not significant; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; Student’s t test. (J) LUC/REN showed that ERF4 inhibits MYB52 activation of the PMEI6, PMEI14, and SBT1.7 promoters. For each co-transformation, the value represents mean ± sd from three biological replicates. n.s., not significant; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; Student’s t test.

To investigate how the ERF4-MYB52 interaction affects their transcriptional activities, an effector plasmid of Pro35S:MYB52 and reporter plasmids of ProPMEI6, 14, or SBT1.7:LUC were constructed and dual-LUC transient transcriptional activity assays were performed in Arabidopsis protoplasts (Figure 7, H). Pro35S:MYB52 co-transformed with either reporter plasmid showed no influence on LUC activity, indicating that MYB52 did not activate promoters containing the GCC-box motif. When Pro35S:ERF4 and Pro35S:MYB52 were co-transformed together with either reporter plasmid, LUC activity was significantly enhanced in comparison with co-transformations without Pro35S:MYB52 (Figure 7, I). This suggests that the transcriptional suppression of ERF4 to its downstream genes was inhibited by MYB52. Similarly, the ERF4-MYB52 interaction decreased the activating regulation of both PMEI6, 14, and SBT1.7 by MYB52, compared with a single co-transformation of Pro35S:MYB52 with either effector plasmid (Figure 7, J).

To test whether ERF4 and MYB52 antagonize each other by forming a non-DNA binding complex, we constructed effector plasmids of Pro35S:ERF424-87 and Pro35S:MYB521-106 that lacked their transcriptional repression/ADs and thus could not regulate downstream targets even if they still had DNA binding activity. Trans-activation assays demonstrated that co-transformation of one TF with the other’s DNA-BD could also restore LUC activity (Supplemental Figure S20), suggesting that ERF4 and MYB52 interfere with each other’s transcriptional activity via the sequestration of their DNA-BDs. These competitive transcriptional activity assays further confirmed the competitive EMSA results that ERF4 and MYB52 attenuate each other’s regulation activity to downstream target genes by forming a non-DNA binding complex.

To further dissect the relationship between ERF4 and MYB52 in the regulation of pectin DM, we generated an erf4-2 myb52 double mutant. The mucilage phenotype and sugar content of the NM and AM layers of this double mutant are indistinguishable from that of the wild type (Figure 8, A and B and Supplemental Table S1). Furthermore, the expression of PMEI13, 14, and 15 was increased whereas PMEI6 and SBT1.7 were downregulated in erf4-2 myb52 compared with the wild type (Figure 4, B). However, they all presented a compromised expression pattern compared with their expression levels in erf4-2 and myb52, respectively. Consequently, PME activity and HG DM of erf4-2 myb52 and wild-type seeds were similar (Figures 4, A and 8, C), suggesting a complementary effect on DM in the erf4-2 myb52 seed mucilage. Taken together, these results suggest that ERF4 and MYB52 play completely opposite roles in the same pathway in regulating pectin DM in the seed coat.

Figure 8.

ERF4 and MYB52 antagonize each other’s function in regulating pectin DM. (A) RR staining showed genetic interactions between ERF4 and MYB52. Mature dry seeds were shaken in deionized water with 0.01% RR at 200 rpm for 2 h. Bars = 200 μm. (B) Thickness of the AM layers. Measurements were made from the top to the bottom of the red halo across the short axis. Data represent average thickness ± sd from three independent biological replicates. For each biological replicate, more than 20 seeds were measured. The average thickness of wild-type seeds was set to 100%. n.s., not significant; ***, P < 0.001; Student’s t test. (C) Relative PME activity of total protein extracts from developing seed coat of wild-type, erf4-2, myb52, and erf4-2 myb52 double mutant. The values were measured according to gel diffusion and were normalized to average wild-type activity (=1). Total protein was extracted from three different batches of seed coats as biological replicates. Each batch of seed coats was pooled from ∼100 siliques from more than 50 plants. Values are means ± sd from three independent biological replicates. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; Student’s t test. (D) Relationships among TFs that are involved in DM modification and the transcriptional regulatory network of ERF4–MYB52 in the seed coat. (E) A model showing that pectin DM is under a fine-tuned regulation of the ERF4–MYB52 transcription complex in the seed coat. ERF4 and MYB52 interact and suppress each other’s function in binding downstream genes encoding PMEIs and a protease, SBT1.7. ERF4 promotes pectin DM by directly suppressing PMEI13, PMEI14, PMEI15, and SBT1.7, and indirectly suppressing PMEI6 expression by preventing MYB52 from binding to its promoter. MYB52 negatively regulates pectin DM by direct transcriptional activation of PMEI6, PMEI14, and SBT1.7, and by indirect activation of PMEI13 and PMEI15 through inhibition of the binding of ERF4 to their promoters.

Discussion

ERF4 plays a regulatory role in seed coat mucilage development

ERF4 has been implicated in diverse processes during plant growth and development (McGrath et al., 2005; Koyama et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2017; Riester et al., 2019), but its role in pectin methylesterification has not been reported. Here, we have demonstrated that ERF4 is involved in modulating PME activity, which leads to a post-deposition modification of seed coat mucilage DM. ERF4 is predominantly expressed in the seed coat during the early stages of embryogenesis (7–10 DPA) and to a lesser extent at ∼13 DPA (Figure 1 and Supplemental Figures S1, S2). However, in contrast to HMS (Levesque-Tremblay et al., 2015), the role of ERF4 in seed coat mucilage is independent from its role in the embryo (Figures 2,A, 3,A, and 4,A and Supplemental Table S2).

The DM of mucilage is associated with its adhesion to the seed coat, which in turn is reflected by the amounts of pectic polysaccharides present in the NM and AM layers. In mutants including luh/mum1, stk, pmei6, and sbt1.7, seed mucilage extrusion was completely abolished (Rautengarten et al., 2008; Huang et al., 2011; Saez-Aguayo et al., 2013; Ezquer et al., 2016). However, in other mutants, there is a re-partitioning of mucilage between the NM and AM layers. For example, myb52, pmei14, and fly1 seeds have more polysaccharide in their AM layers than wild type (Voiniciuc et al., 2013; Shi et al., 2018). By contrast, less polysaccharide is present in the AM layers of blh2 blh4 and pme58 seeds (Xu et al., 2020). Our study demonstrates that erf4, blh2 blh4, and pme58 seeds are comparable since mucilage adhesiveness is decreased and its DM is increased (Figures 2, 3; Supplemental Table S1, and Supplemental Figures S8–S10). A lower DM level may facilitate the Ca2+ ion-mediated formation of the so-called “egg-box” structures between HG molecules (Micheli, 2001; Pelloux et al., 2007; Willats et al., 2001a, 2001b; Wolf et al., 2009). A reduction in labeling of erf4 seed mucilage by 2F4 is consistent with a decrease in such “egg-box” domains (Supplemental Figure S11). We conclude that the decreased DM of HG in erf4 seed mucilage contributes to the lower adhesiveness of its AM layer.

It is notable that EDTA extracted slightly less NM than water in wild-type and erf4 seeds (Figure 2, C). This is not consistent with the assumption that Ca2+ chelation by EDTA increases the extractability of mucilage. Seed coat mucilage RG-I has been reported to form multi-chain complexes and/or twisted fibrils, which may affect the extractability of seed mucilage by different aqueous reagents (Wiliams et al., 2020). Nevertheless, additional studies of the properties of RG-I-HG under different extraction conditions are required to understand the factors that control mucilage extractability. We suggest that even though Ca2+chelation by EDTA may loosen pectin structure as observed in our study (Supplemental Figure S7) and in a previous study (Voiniciuc et al., 2013), the extractability of the seed mucilage may not change or may even decrease. Thus, slightly smaller amounts of mucilage were extracted with EDTA than with water in seeds of erf4 and wild type (Figure 2, C).

ERF4 positively modulates HG DM by suppressing PMEI13, 14, 15, and SBT1.7

The ERF family is a member of the AP2/ERF superfamily, which is defined by the presence of the AP2/ERF DNA-BD (Nakano et al., 2006) . The ERF TFs are either transcriptional activators or repressors depending on the action of the protein on downstream target genes. Some of these proteins contain a plant-specific repression domain, the EAR motif, with a conserved sequence of DLNxxP or LxLxL which is present in Arabidopsis ERF4 (Ohta et al., 2001;Tiwari et al., 2004; Nakano et al., 2006). Therefore, the ERF4 protein contains an AP2/ERF domain and an EAR motif at its N- and C-terminus, respectively (Figure 6, A), and is likely a transcription repressor. Indeed, trans-activation assays confirmed that ERF4 is a transcriptional repressor that binds to the cis-acting element known as the GCC-box (Fujimoto et al., 2000; Tiwari et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2005). Nevertheless, the downstream target genes of ERF4 remain to be determined.

Our global gene expression studies indicated that ERF4 transcriptionally repressed a subset of genes including 11 PMEI genes and SBT1.7, which have a role in altering the DM of seed coat mucilage HG. ERF4 did indeed suppress the expression of PMEI13, 14, 15, and SBT1.7 by directly binding to the GCC-box motif (Figures 4, B and 5). PMEI13, 14, 15, and SBT1.7 all inhibit PME activity (Figure 4, A), leading us to conclude that the reduced PME activity is due to transcriptional up-regulation of the PMEI genes and SBT1.7 in the erf4 seed coat. The mucilage defect in erf4 is partially rescued in mutants lacking PMEI13 or PMEI14, which provides genetic evidence that ERF4 functions upstream of PMEI13, 14 (Figure 5, H and Supplemental Figure S17). However, the seeds of erf4-2 sbt1.7 and sbt1.7 resemble one another in terms of mucilage extrusion. We suggest that SBT1.7 is not primarily regulated by ERF4. Nevertheless, the possibility cannot be excluded that other PMEI genes including PMEI6, contribute to the mucilage phenotype, since their expressions were also upregulated in erf4 seeds (Supplemental Figure S12, D and Supplemental Data Set S1).

Function of PMEI13 and PMEI15 in seed mucilage maturation

The Arabidopsis genome encodes 66 PME and 71 PMEI genes (Wang et al., 2013). Some of these genes are preferentially expressed in the seed integument (http://bar.utoronto.ca/efp/cgi-bin/efpWeb.cgi). However, to date only one PME (PME58) and two PMEIs (PMEI6 and PMEI14) have been shown to be involved in DM of seed coat mucilage HG (Saez-Aguayo et al., 2013; Shi et al., 2018; Turbant et al., 2016). PMEI is believed to physically interact with PME (at a 1:1 ratio) and thereby modulate DM (Wolf et al., 2009; Sénéchal et al., 2015). However, there is no evidence that PME58 interacts with PMEI6 or PMEI14, indicating that other PMEs and PMEIs participate in seed mucilage maturation (Turbant et al., 2016). In this study, we have provided evidence that PMEI13 and PMEI15, which function in regulating seed mucilage DM, are direct targets of ERF4 (Figure 5). Since PME activity is increased in the pmei13 and pmei15 mutants, we conclude that PMEI13 and PMEI15 encode functional PMEIs, although PMEI15 has little if any role in seed mucilage HG DM. pmei13 seeds are similar to pmei14 and pme58 seeds, as they release mucilage normally but re-partition the mucilage between NM and AM layers. This is distinct from pmei6 seeds, which have a severe mucilage extrusion defect. PMEI13 and PMEI15 are predominantly expressed in the seed coat during the early stages of embryogenesis (4–7 DPA; Supplemental Figures S1, S2, S15). Such a spatial restriction of their expression suggests that they function exclusively in seed coat mucilage maturation.

ERF4 and MYB52 interact with each other to regulate pectin DM antagonistically

In eukaryotes, TFs typically work in combination with one another to promote or inhibit each other’s transcriptional activity in controlling the expression of target genes. The ERF–MYB transcriptional complex has been reported to control many aspects of plant development either coordinately or antagonistically in several plant species (Zeng et al., 2015; Yao et al., 2017a; Zhang et al., 2018b, 2020). Here, we have provided evidence for an interaction between Arabidopsis ERF4 and MYB52 (Figure 6). We showed that MYB52 inhibits the binding of ERF4 to PMEI13, 14, 15, and SBT1.7 and enhances their transcription activity (Figure 7, A–D, I). Thus, the ERF4–MYB52 interaction represses the transcriptional suppression of PMEI13, 14, 15, and SBT1.7 by ERF4, which decreases PME activity in the seed coat. The ERF4–MYB52 interaction also prevents MYB52 from binding to PMEI6, 14, and SBT1.7 promoters, and reduces its activating regulation (Figure 7, E–G, J), thereby enhancing PME activity in the seed coat.

We obtained genetic evidence that PME activity, HG DM, and mucilage release of the erf4-2 myb52 double mutant and wild type are virtually identical (Figures 3, A and 8, A–C, and Supplemental Table S1). This together with the expression patterns of downstream genes in erf4-2, myb52, and erf4-2 myb52 (Figure 4, B) lead us to propose that PMEI13, 14, and 15 are regulated by ERF4, whereas PMEI6 and SBT1.7 are under positive regulation by MYB52, although other TFs may also be involved. The reciprocal transcriptional inhibition between ERF4 and MYB52 provides insights into the mechanisms that have evolved in plants to regulate PME activity.

The ERF4 protein contains an N-terminal AP2/ERF domain involved in DNA recognition and a C-terminal repression domain containing the EAR motif. MYB52 belongs to the R2R3–MYB family, the members of which contain at their N-terminus two adjacent MYB repeats that are involved in DNA binding (Ogata et al., 1995; Stracke et al., 2001). Such MYBs are known to be transcriptional activators (Shi et al., 2018). The DNA-BD and the repression/AD must operate together to modulate the rate of transcription initiation of target genes (Ptashne, 1988). Our Y2H analyses showed that intact AP2/ERF and Myb DNA-BDs are required for the ERF4–MYB52 interaction (Figure 6, A and Supplemental Figure S19), suggesting a model in which MYB52 and ERF4 bind to each other and prevent each other from binding to DNA. Trans-activation assays with truncated MYB and AP2/ERF DNA BDs, which can inhibit functional ERF4 and MYB52 transcriptional activities, respectively (Supplemental Figure S20), further substantiate our hypothesis. We conclude that MYB52 and ERF4 inhibit each other’s DNA binding ability via direct protein–protein interaction through a sequestration mechanism.

Proposed transcriptional regulatory network for pectin DM in the seed coat

The transcriptional regulatory network of HG DM in Arabidopsis seed coat has been partially elaborated (Figure 8, D). LUH/MUM1, STK, MYB52, and BLH2/BLH4 are either positive or negative regulators of mucilage methylesterification and are transcriptionally associated with each other in regulating target genes (Ezquer et al., 2016; Shi et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2020). We have shown that ERF4 expression was suppressed by MYB52, STK, and LUH/MUM1 but was promoted by BLH2/BLH4 (Supplemental Figure S18). We also discovered that some TFs regulate the expression of the same target genes. For example, PMEI14 and SBT1.7 are targets of both MYB52 and ERF4, whereas PMEI6 is a target of STK and MYB52. Together, these results suggest that the regulatory network underlying pectin DM is more complex than expected.

Based on our studies, we propose a model for the role of the ERF4–MYB52 complex in the regulation of pectin DM (Figure 8, D and E). ERF4 and MYB52 interact and suppress each other’s transcriptional activity on downstream targets. ERF4 negatively regulates PMEI13, 14, 15, and SBT1.7 expression by directly binding to their regulatory elements and suppresses PMEI6 indirectly by antagonizing MYB52, giving rise to positive regulation of pectin DM. MYB52 activates PMEI6, PMEI14, and SBT1.7 by directly binding to their promoters and positively regulates PMEI13 and PMEI15 expression indirectly by suppressing ERF4 activity, which in turn negatively regulates pectin DM in the seed coat. Taken together, our findings reveal that ERF4 and MYB52 antagonistically regulate genes controlling the DM of HG in seed coat mucilage.

The DM of HG needs to be finely controlled

Previous studies have shown that seed coat mucilage extrusion defects may result from an increase (luh/mum1) or a decrease (pmei6 and stk) in the DM of HG (Huang et al., 2011; Saez-Aguayo et al., 2013; Ezquer et al., 2016). Thus, the DM of HG must be maintained at a specific level for normal seed coat mucilage extrusion. Controlling HG DM has also been implicated in numerous other plant growth processes (Wormit and Usadel, 2018). For example, overexpressing AtPMEI2 results in enhanced root elongation whereas hypocotyl growth is delayed. Hypocotyl elongation and culm elongation is also restrained by overexpressing AtPMEI4 and OsPMEI28, in Arabidopsis and rice (Oryza sativa), respectively (Pelletier et al., 2010; Nguyen et al., 2017). Arabidopsis pollen tube growth is inhibited by AtPMEI1 but is promoted by the PME encoded by VANGUARD1 (Jiang et al., 2005; Röckel et al., 2008). Pectin DM regulated by AtPME5 also contributes to an increase in the elasticity of the shoot apical meristem (Peaucelle et al., 2011). Recently, it has been proposed that in leaf pavement cells the DM of HG rather than turgor pressure is the driving force for cell expansion and cell shape (Haas et al., 2020). PMEs and PMEIs have also been implicated in fruit ripening (Reca et al., 2012), in plant stress responses (Bethke et al., 2014; Lionetti et al., 2017), and in mediating unilateral cross-incompatibility (Zhang et al., 2018a). These findings suggest a complex relationship between DM and plant growth processes and that PME activity must be tightly controlled to fine-tune pectin’s biophysical and biochemical properties. The antagonistic interaction between the transcription repressor ERF4 and the activator MYB52 provides insights into one of the mechanisms used by Arabidopsis to control the DM of mucilage to further regulate the structure and properties of this extracellular matrix in the seed coat.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

The Arabidopsis T-DNA insertion lines erf4-1 (SALK_200761), erf4-2 (SALK_073394), myb52 (SALK_138624), blh2 blh4 double mutant (CS16377), pmei13-1 (GABI-601A06), pmei13-2 (SALK_038767), pmei14 (SALK_206157), pmei15-1 (SALK_106719), pmei15-2 (SALK_053746), sbt1.7 (GABI-140B02), pme58 (SALK_055262), and fly1 (CS67937) were obtained from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre (http://arabidopsis.info/). The erf4-2, myb52, pmei14, sbt1.7, pme58, fly1, and blh2 blh4 mutants have been described previously (Rautengarten et al., 2008; Koyama et al., 2013; Voiniciuc et al., 2013; Shi et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2020). Seeds were stratified for 3 days at 4°C and then geminated on 1/2 Murashige and Skoog solid medium (pH 5.8) at 22°C under long-day (16-h light/8-h dark) conditions in a growth chamber (65% relative humidity). The lights used were white light (Fluorescent light, Philips TL5 14/865 bulb, 6500K, 120 μmol m−2 s−1). Seven-day-old seedlings were transferred to soil (a 1:1 mixture of Pindstrup Substrate and vermiculite) and grown under the same conditions. Double mutants were obtained by crossing erf4-2 with either myb52, pmei13-1, pmei14, pmei15-1, or sbt1.7 single mutants. In all comparative analyses for mucilage phenotypes, the seeds used were collected from mutants and wild-type plants that had been grown and harvested at the same time.

PCR-based genotyping

Homozygous T-DNA insertion lines for all single and double mutants were identified by PCR using genomic DNA and primers (Supplemental Table S3) provided by T-DNA Primer Design (http://signal.salk.edu/tdnaprimers.2.html). Plants with PCR products only obtained for the insertion border and not with primers flanking the insertion sites were regarded as homozygous lines.

Expression analysis and GUS staining of plant tissues

Developing seeds at 7–10 DPA were harvested from about 100 siliques and scattered on a glass slide (Xu et al., 2020). The embryos and most of the endosperm were squeezed out by pressing the seeds with another slide. The seed coats were then harvested, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and kept at −80°C. Three different batches of seeds or seed coats of wild type, erf4-2, myb52, erf4-2 myb52, luh, stk, blh2 blh4, pmei13, pmei15, and Pro35S:ERF4 were collected as biological replicates. For each replicate, the seeds or seed coats of the same batch were harvested from more than 50 plants. Total RNA was extracted from three biological replicates using the RNeasy plant mini kit (Qiagen). RNA (1 μg) was used as the template for first-strand cDNA synthesis with the oligo(dT) primer and the PrimeScript RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The qPCR assay was performed using 1/20 diluted cDNA as templates in the reactions containing SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (TaKaRa). The qPCR assay was conducted in triplicate in an ABI 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System with the primers listed in Supplemental Table S4. The relative expression of genes was calculated by normalizing against AtACTIN2 (Dekkers et al., 2012) with the method in analyzing the data. Two technical replicates were performed for each biological replicate. The Expression data are means and sd from three independent biological replicates from the three different batches of seeds or seed coats. AtACTIN2 was also used as a loading control in the RT-PCR analysis for detecting of transcripts.

The ERF4 promoter region of 1,965 bp preceding the transcriptional ATG start codon was amplified by PCR using wild-type genomic DNA as template. After purification with the EasyPure PCR Purification Kit (TRANSGEN BIOTECH), the PCR products were recombined into the PBI121 binary vector with an Xba I site to generate ProERF4:GUS. After Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of wild-type plants, histochemical staining of positive transformants was performed using the GUS staining kit (Solarbio) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The GUS-stained tissues were examined using a MDG29 stereoscopic microscope (LEICA) equipped with a Leica MC190 camera. Primers used are listed in Supplemental Table S5.

In situ hybridization

In situ hybridization analysis was performed as previously described (Hu et al., 2016). In brief, wild-type siliques at 4, 7, 10, and 13 DPA were fixed, dehydrated, embedded, sectioned, and attached to adhesive slides. Gene-specific fragments of ERF4 and MYB52 were amplified by PCR using specific primers. The DNA fragments were then individually cloned into the pGEM-T vector. Digoxigenin-labeled sense and antisense RNA probes were generated in vitro from either T7 or SP6 promoters using the Digoxigenin RNA Labeling kit (Roche). The in situ hybridization procedure was performed as previously described (Mayer et al., 1998). The blocking reagent, anti-Digoxigenin antibody, and NBT/BCIP Stock Solution used in the experiments were purchased from Roche. The antisense and sense samples were operated in parallel throughout the procedure. Images were visualized and captured with a light microscope (Nikon).

RR staining and morphological analysis

For mucilage extrusion analysis, whole mature dry seeds were suspended in deionized water (pH 9.0), aqueous 0.01% (w/v) RR (Sigma–Aldrich), 50 mM CaCl2 (pH 6.5), 50 mM EDTA (catalog no. E1170-100, Solarbio; pH 6.0 and 8.0), and 1 M Na2CO3 (pH 11.0) and gently shaken by hand or in an incubator (2 h at 28°C and 200 rpm). After RR staining, seeds were rinsed in deionized water and visualized with a bright-field microscope (Nikon). For statistical analyses, three different batches of seeds were treated with the same solution as biological replicates. For each biological replicate, the thickness across the short axis of mucilage halo of more than 20 seeds of the same batch was measured with ImageJ software (https://imagej.en.softonic.com/download). Data represent average thickness and sd from three independent biological replicates, with the average thickness of wild-type seeds being set to 100%. For the morphological analysis of seed coat differentiation, developing siliques at 4, 7, 10, and 13 DPA of wild type and erf4-2 were fixed overnight at 4°C in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.0) containing 2.5% (w/v) glutaraldehyde, and then for 1 h in 1% (w/v) osmium tetroxide. After dehydration with a gradient series of ethanol (30%–100%, v/v), samples were embedded in Spurr’s resin and cut into 1-μm sections. The sections were stained with 0.5% (w/v) Toluidine Blue O for 5 min, and then visualized and photographed with a bright-field microscope (Nikon).

Gene cloning and plant transformation

The full-length CDS of ERF4 and MYB52 was amplified by PCR using wild-type cDNA as a template and then recombined into the pCAMBIA35tlegfps2#4 binary vector with Kpn I/Xba I restriction sites to generate Pro35S:ERF4/MYB52 overexpressing vectors. The full-length CDS of ERF4 was also recombined into a modified pCAMBIA1300 binary vector (Pro35S:Myc) with the Kpn I site to obtain the Pro35S:Myc-ERF4 overexpression vector. The vectors were introduced into Agrobacterium strain GV3101, which was then used to transform Arabidopsis wild-type or erf4-2 mutant plants by a floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). Positive transformants were selected on 1/2 MS medium containing 25 mg L−1 hygromycin or 50 mg L−1 kanamycin.

Mucilage extraction and monosaccharide composition analysis

Briefly, mature dry seeds (5 mg, with three biological replicates) from wild-type or mutant plants were placed in 2-mL tubes containing 1 mL deionized water. The NM was released by shaking for 2 h at 28°C and 200 rpm. The seeds were washed three times and the supernatants combined in 10-mL glass tubes. The seeds in 1 mL deionized water were then treated for 20 s with an ultrasonic probe to release the AM as described (Zhao et al. 2017). The seeds were washed three times with water and the combined supernatants were placed in 10-mL glass tubes. NM was also solubilized by treating seeds for 2 h at 28°C and 200 rpm with 50 mM EDTA (pH 8.0). AM was then released by shaking seeds for 20 min at 20 movements/s in EDTA using a TissueLyser II (Qiagen). Images of RR-stained seeds post-extraction are shown in Supplemental Figure S6. The mucilage extracts were lyophilized with a FreeZone freeze dryer (LABCONCO) and then used for monosaccharide composition analysis (EDTA extracts are dialyzed [molecular weight cut off 3,500] for at least 24 h against flowing deionized water). The mucilage in NM and AM fractions was hydrolyzed for 2 h with 2-M trifluoroacetic acid at 110°C and the released monosaccharide quantified by HPLC (Waters 2695 and 2998) as their 1-phenyl-3-methyl-5-pyrazolone derivatizes as described (Shi et al., 2018).

Determination of PME activity in the seed coat

Gel diffusion assays were performed to determine PME activity as described (Xu et al., 2020). In brief, developing seed coats from about 100 siliques at 7–10 DPA were ground to a paste in 400 µL of extraction buffer (1 M NaCl, 12.5 mM citric acid, and 50 mM Na2HPO4, pH 6.5) using a mortar and pestle. Three different batches of seed coats were independently processed as biological replicates. For each biological replicate, the resulting homogenate was shaken for 1 h at 4°C and then centrifuged for 15 min at 20,000 × g. Protein concentrations in the supernatant were determined using the Bradford reagent (Bradford, 1976). Equal quantities of proteins (10 µg) in the same volume (20 µL) were loaded into 6-mm-diameter wells in 1% agarose gels containing 0.1% (w/v) of esterified citrus fruit pectin (85% esterified, Sigma–Aldrich), 12.5 mM citric acid, and 50 mM Na2HPO4, pH 6.5. The gels were kept overnight at 28°C, stained for 45 min with 0.01% RR, and then washed five times with water (1 h/time). The gels were photographed and the red-stained areas were quantified with Image J software. The measurements were performed in triplicate with protein extracts from the different batches of seed coats and relative PME activity was normalized with the wild-type average area being set to 100%.

Determination of DM in the seed mucilage

Three different 20 mg batches of seeds were collected from more than 50 plants of wild type and mutants. For each replicate, seed mucilage was extracted in 400-µL 50 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) on a TissueLyser II (Qiagen). Methanol was released from mucilage by alkaline de-esterification for 1 h at 4°C using 2 M NaOH. The solutions were neutralized with 2 M HCl and the released methanol oxidized for 15 min at 25°C with alcohol oxidase (0.5 U, Sigma–Aldrich). A solution of 20 mM 2, 4-pentanedione in 2 M ammonium acetate and 50 mM acetic acid was then added and kept for 15 min at 60°C. The solutions were cooled on ice and their A412 nm was measured with a plate reader (Tecan). The methanol content was calculated as the amount of formaldehyde produced from methanol by alcohol oxidase using a standard calibration curve (Klavons and Bennett, 1986). Sulfuric acid containing 0.125 M sodium tetraborate (220 µL) was added to 40 µL of the remaining saponified mucilage supernatant on ice. The mixture was then heated for 5 min at 100°C. m-Hydroxybiphenyl (4 µL of a 1.5 mg/mL solution) was then added to the cooled solutions (Blumenkrantz and Asboe-Hansen, 1973). The A525 nm was read with a plate reader (Tecan). GalA was quantified using a d-(+)-galacturonic acid monohydrate (Sigma–Aldrich) standard curve. DM = total methanol content (µmol)/total GalA content (mg) × 100%.

Immunolabeling assays

mAbs that recognize de-esterified HG (catalog code CCRC-M38, PlantProbes, 1:200 dilution), low methylesterified HG (catalog code JIM5, PlantProbes, 1:200 dilution), fully methylesterified HG (catalog code JIM7, PlantProbes, 1:200 dilution), and Ca2+-linked HG dimers (catalog code 2F4, PlantProbes, 1:100 dilution) were used for whole-seed immunolabeling analysis. All these mAbs can be purchased from PlanProbes (www.palntprobes.net). CCRC-M38, JIM5, and JIM7 mAbs were used with PBS buffer (140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 8.0 mM Na2HPO4, 1.5 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4), whereas the 2F4 mAb required TCS buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.2, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 150 mM NaCl). Whole intact dry seeds were first blocked for 1 h at 37°C in PBS/TCS buffer (MPBS/MTCS) containing 3% (w/v) fat-free milk powder and then labeled for 1.5 h at 37°C with 10-fold MPBS/MTCS-diluted primary antibody. Seeds were then washed three times with PBS/TCS buffer. Seeds were then treated for 1.5 h at 37°C in the dark with a 200-fold MPBS/MTCS-diluted AlexaFluor488-tagged donkey anti-rat IgG (Thermofisher) secondary antibody for JIM5 and JIM7, and a donkey anti-mouse IgG (Thermofisher) for CCRC-M38 and 2F4. The seeds were treated for 15 min with Calcofluor White (Sigma–Aldrich) diluted five times in PBS/TCS buffer. Images were captured using a FluoView FV1000 spectral confocal laser microscope (OLYMPUS) with a 405-nm and 488-nm laser. Fluorescence emissions were recorded between 410 and 500 nm for Calcofluor and between 500 and 630 nm for Alexa fluor488. For each immunolabeling experiment, the same settings for image acquisition were applied.

Transcriptome analysis

Three different batches of developing seeds were harvested from wild type and erf4-2 as biological replicates. For each replicate, seeds at about 7 DPA were pooled from more than 50 plants. For RNA-seq analysis, total RNA was extracted using the Plant RNA Purification Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Genomic DNA was removed using DNase I (TaKara). For each biological replicate, sequencing libraries were generated and sequenced by OE Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). RNA quality was determined by an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). RNA concentration was measured by spectrophotometer (NanoDrop 2000). Only high-quality RNA samples (OD260/280 = 1.8–2.2, OD260/230 ≥ 2.0, RNA Integrity Number ≥6.5, 28S:18S ≥1.0, total amounts >10 μg) were subjected to further analysis. RNA libraries were prepared for sequencing using standard Illumina protocols with the TruSeq Stranded mRNA LT Sample Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. These RNA libraries were sequenced on an Illumina sequencing platform (Illumina HiSeq X Ten) as 125-bp/150-bp paired-end reads. The raw paired-end reads were trimmed and quality controlled by Fastp (https://github.com/OpenGene/fastp). Clean reads were obtained by removing low-quality reads and reads containing multiple Ns. Then the clean reads were separately aligned to The Arabidopsis Information Resources 10 (TAIR10) genome with orientation mode using the hisat2 (Version 2.2.1.0) software. Principal component analysis was used to evaluate the data. The expression level of each transcript was calculated according to the Fragments Per Kilobase of exon per Million mapped reads (FPKM) method. RSEM (http://deweylab.biostat.wisc.edu/rsem/) was used to quantify gene abundance. For differential expression analysis, we identified DEGs using the DESeq (Version1.18.0) software. The R package functions “Estimate Size Factors” and “nbinom Test,” Padj values < 0.05 and Fold Changes >1.5 were set as the threshold for significantly differential expression analysis.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Proteins were induced and purified as described (Yuan et al., 2014). Briefly, the CDS of MYB52 was cloned into the pGEX4T-1 vector to generate the GST-MYB52 fusion protein, whereas the CDS of ERF4 was cloned into pMAL-C2X vector to generate the MBP-ERF4 fusion protein. The resulting plasmids were separately transformed into Escherichia coli strain BL21 cells for induction of fusion proteins. Empty pGEX4T-1 and pMAL-C2X vectors were also transformed to obtain GST and MBP tags for control experiments. Proteins were induced by adding isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) to 0.5 mM overnight at 16°C. The GST tag and GST-MYB52 fusion protein were purified using a GST-tag Protein Purification Kit (Beyotime, P2262) with the BeyoGold GST-tag Purification Resin according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The MBP tag and MBP–ERF4 fusion protein were purified using the PurKine MBP-Tag Protein Purification Kit (Dextrin) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Oligonucleotide probes were synthesized with their 5′-end labeled with biotin. To prepare double strand probes, forward and reverse oligonucleotide probes were heated for 5 min at 95°C in the annealing buffer and then cooled to room temperature. EMSAs were performed using a LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (ThermoFisher) according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer. All primers and oligonucleotide probes used are listed in Supplemental Table S6.

ChIP-qPCR assay

Three different batches of siliques were collected as independent biological replicates. For each replicate, about 2 g of immature siliques at 7–10 DPA was harvested from wild-type and Pro35S:Myc-ERF4 or Pro35S:Myc-MYB52 transgenic plants. After washing two times with ddH2O, the siliques were fixed for 10 min under vacuum in 37 mL 1% formaldehyde. Glycine (2.5 mL 2 M) was added to terminate crosslinking and the tissue was then ground to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen. Immunoprecipitation of chromatin was performed as described (Gendrel et al., 2005) with the anti-Myc antibody (catalog no. ab9132, Abcam, 1:4000 dilution). The precipitated DNA was recovered and the enrichment of DNA fragments in the immunoprecipitated chromatin was quantified by qPCR analysis using primers listed in Supplemental Table S4. The promoter regions that do not contain a GCC-box motif were used as negative controls. The relative enrichment data represent means and sd from three independent biological replicates from different batches of siliques.

Dual-luciferase transient transcriptional activity assay