Abstract

Objectives

To examine the safety of an agonist-type treatment, lisdexamfetamine (LDX), at 250 mg/day among adults with methamphetamine (MA) dependence.

Design

A dose-escalating, phase-2, open-label, single-group study of oral LDX at two Australian drug treatment services.

Setting

The study was conducted at two Australian stimulant use disorder treatment clinics.

Participants

There were 16 participants: at least 18 years old, MA dependent for at least the preceding 2 years using ICD-10 criteria, reporting use of MA on at least 14 of the preceding 28 days.

Interventions

Daily, supervised LDX of 100–250 mg, single-blinded to dose, ascending-descending regimen over 8 weeks (100–250 mg over 4 weeks; followed by 4-week dose reduction regimen, 250–100 mg). Participants were followed through to week 12.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes were safety, drug tolerability and regimen completion at the end of week 4. Participants were followed to week 12. Secondary outcomes included: change in MA use; craving; withdrawal; severity of dependence; risk behaviour; change in other substance use; medication acceptability; potential for non-prescription use; adherence and neurocognitive functioning.

Results

Fourteen of 16 participants (87.5%) completed escalation to 250 mg/day. Two participants withdrew from the trial in the first week: one relocated away from the study site, the other self-withdrew due to a possible, known side effect of LDX (agitation). There was one serious adverse event of suicidal ideation which resolved. All other adverse events were mild or moderate in severity and known side effects of LDX. No participant was withdrawn due to adverse events. MA use decreased from a median of 21 days (IQR: 16–23) to 13 days (IQR: 11–17) over the 4-week escalation period (p=0.013).

Conclusions

LDX at a dose of up to 250 mg/day was safe and well tolerated by study participants, warranting larger trials as a pharmacotherapy for MA dependence.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12615000391572.

Keywords: substance misuse, clinical pharmacology, clinical trials

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first to demonstrate the safety, tolerability and acceptability of higher doses of lisdexamfetamine (LDX) in people with methamphetamine (MA) dependence than those currently approved in the treatment attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and binge eating disorder.

There are currently no pharmacotherapies approved for the treatment of MA dependence, research into medication options could provide a complementary adjunct to the success of psychosocial therapies.

This pilot study demonstrated the safety and tolerability of LDX in this population, which may encourage further larger scale trials of LDX as a pharmacotherapy for MA dependence.

The small sample size and short duration of treatment is typical of pilot safety studies, limiting the clinical extrapolation of findings.

The study is not powered to explore efficacy of LDX and this precludes more sophisticated statistical analysis.

Introduction

Amphetamine-type stimulants, including methamphetamine (MA), make up the second most commonly used illicit drug class. An estimated 29 million people used amphetamines in 2019,1 with 7 million estimated to be dependent.2 Poor health outcomes are seen particularly among people who use MA several times a week,3 including psychosis, depression, anxiety, bloodborne virus transmission, sexually transmitted infections, and cardio/cerebral vascular events.4 5

Currently, treatment for MA dependence is based on psychological therapies such as cognitive–behavioural therapy.6 7 Psychological therapies are labour-intensive and predicated on high levels of attendance and participation by patients. No pharmacotherapy has yet achieved comparable efficacy, and there are as yet none licensed for the treatment of MA dependence. Though agonist therapies show some promise,8 their efficacy for treatment of MA dependence is uncertain, with one systematic review showing no benefit over placebo, although limitations in retention and power of published studies were noted.9 Dexamphetamine, an MA agonist, has similar neurochemical and behavioural effects to MA,10 and has been used off-label for both amphetamine and MA dependence in the UK11 12 and Australia.13

Lisdexamfetamine (LDX) is a pharmacologically inactive prodrug of dexamphetamine approved for the treatment of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in Australia, Brazil (in children only), Canada, several European countries, the UK and the USA14 and more recently for binge eating disorder (BED) in Australia and the USA. Potential advantages of LDX over immediate release dexamphetamine include once-daily dosing, a slower onset, lower peak concentration, longer duration of action and lower abuse potential.15 LDX presents a candidate pharmacotherapy for MA dependence.

There are no clinical trial data on the effectiveness of LDX for the treatment of MA dependence. Chronic use of high doses of MA may lead to physiological adaptation so that a dose higher than the licenced therapeutic range of medication is required.9 For the treatment of ADHD and BED in stimulant-naïve populations, LDX is licensed for doses ranging from 30 to 70 mg/day. A previous study of dexamphetamine has trialled doses up to 110 mg for this population without serious adverse events (SAEs),16 which is approximate to 275 mg of LDX using a mole weight equivalent of 100 mg LDX to 40 mg dexamphetamine.17 The highest dose for which safety data of LDX are available is 250 mg/day, equivalent to 100 mg dexamphetamine, tolerated in a safety and pharmacokinetic study of LDX in non-MA dependent volunteers18 and in participants with clinically stable schizophrenia adherent to antipsychotic pharmacotherapy.19

This study aimed to determine the safety of LDX in people with MA dependence, at doses higher than those currently approved for the treatment of ADHD and BED. The primary objectives of the study were to describe the safety, tolerability and regimen completion of ascending doses of LDX in adults with MA dependence. Secondary objectives included measures of efficacy, drug-liking and neurocognition.

Methods

Trial design

A phase-2, open-label, single-group trial was undertaken at two stimulant use disorder treatment outpatient clinics in New South Wales, Australia.20 All participants provided written, informed consent prior to undergoing study assessments. An independent data safety and monitoring board reviewed safety data during and at completion of the study.

Patient and public involvement

The original idea for the study was proposed by a patient at the St Vincent’s Hospital Outpatient Stimulant TreatmentProgramme.

Recruitment and enrolment

Notices were displayed at clinics at both sites, as well as at other drug and alcohol services, associated community organisations, and local general practice clinics. Interested individuals either approached or were referred to a research nurse who undertook a standardised prescreening. If basic inclusion criteria and no exclusion criteria were met, potential participants attended a screening visit with a site principal investigator.

Participants

Eligible participants were at least 18 years of age who had been dependent on MA for at least the preceding 2 years, determined by an addiction medicine physician (AD and NE) using International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10) criteria.21 Inclusion additionally required reported use of MA on 14 days or more of the previous 28 days at the time of screening, confirmed by two urine samples positive for MA 1 week apart. Patients who had used dexamphetamine in the previous 4 weeks were excluded, as were those with known sensitivity or previous adverse reaction to LDX or prescribed drugs which may interact with LDX (venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, monoamine oxidase inhibitors), known contraindications to LDX (severe and symptomatic peripheral vascular disease or Raynaud’s phenomenon, significant prior or symptomatic cardiovascular disease, moderate to severe hypertension, glaucoma, phaeochromocytoma, hyperthyroidism, motor and phonic tics, Tourette’s syndrome, high suicide risk, voicing suicidal ideation, active psychosis, severe agitation or unstable use of alcohol or drugs other than MA as assessed by a specialist in addiction medicine22). Patients with well-controlled mild to moderate hypertension on a single antihypertensive agent were permitted, and those with a history of psychosis were permitted on review by a psychiatrist. Pregnant or breastfeeding women and women not willing to avoid becoming pregnant during the study were also excluded.

Study procedures

At the screening visit, informed consent was obtained as well as a detailed medical and substance use history, physical and mental state examinations, an ECG and a urine human chorionic gonadotrophin test (for women of childbearing potential) to verify eligibility.

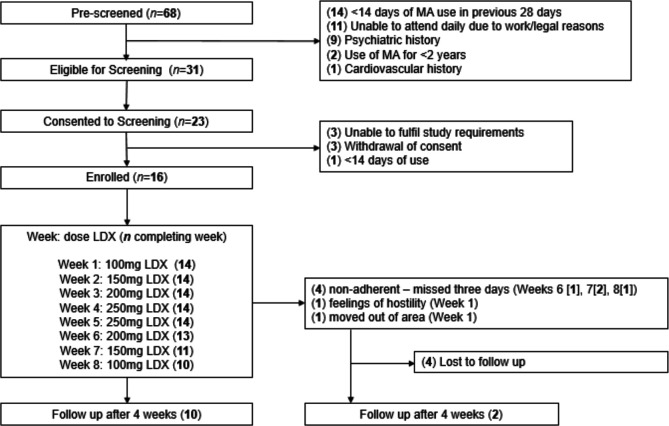

All participants were commenced on a dose escalation regimen of supervised daily dispensing of ascending doses of LDX from 100 to 250 mg over 4 weeks, followed by a 4-week dose reduction regimen from 250 to 100mg, and attended a follow-up visit 4 weeks after ceasing the study drug (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study participant flow chart. LDX, lisdexamfetamine; MA, methamphetamine.

Five capsules were dispensed to each participant daily, with the number containing active study drug or placebo varying with the dose phase to maintain blinding. Both participants and dispensing nurses were aware of dose escalation and reduction, and of the dose range (100–250 mg), but they were blinded to the time points at which the doses changed. Participants received each dose for 7 days, based on the data that steady state for LDX is achieved after 5 days,23 and were reviewed by a medical officer weekly.

Participants not already engaged with psychological therapy were offered concurrent standard of care weekly counselling, although attendance was not mandatory. Participants were offered supermarket vouchers with a value of $A80 at the end of each of six visits: baseline; weeks 1–4 (escalation phase); and follow-up (week 12) (total possible value of $A480).

Criteria for withdrawing participants were: resting heart rate greater than 120 beats per minute (BPM) for more than 60 min; hypertension (two consecutive readings within 1 hour of each other where the systolic blood pressure (SBP) was greater than 160 mm Hg, or the diastolic blood pressure (DBP) greater than 100 mm Hg); clinically significant psychosis; or significant or SAE related to the study drug. Other withdrawal criteria were diversion of study medication, missing more than one planned medical review and missing three or more doses of study drug over a 7-day period. Full details of the study protocol were published prior to study completion.20

Outcome measures

The primary outcomes of the study were the safety, tolerability and regimen completion of ascending doses of LDX in adults with MA dependence.

Safety was assessed with a number of measures. Blood pressure, pulse and temperature were recorded daily. Participants were assessed weekly by a physician and had treatment emergent adverse events (TEAEs) recorded. TEAEs were volunteered by the participants during or between visits, as well through physical examination, laboratory test or other assessments. Severity of TEAEs was determined by a site principal investigator (both addiction medicine specialists). Severity of symptoms was graded as mild if they caused no or minimal interference with usual social and function activities and required no intervention. Moderate TEAEs were those which caused greater than minimal interference with usual social and functional activities, requiring only minimal intervention. Severe TEAEs were classified as those which resulted in an inability to perform usual social and functional activities and medically significant events which required intervention. SAEs were medically significant events that were; fatal or life-threatening; resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity; or required unplanned inpatient hospitalisation. The Psychosis and Hostility items of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)24 were administered weekly. The Insomnia Severity Index,25 Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ9)26 and the Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD7) scale27 were administered every 2 weeks and at follow-up, measuring insomnia, depression and anxiety, respectively. The PHQ1528 was administered to assess for changes to somatic symptoms and weight in kilograms measured every 4 weeks. ECGs were recorded at Baseline and at weeks 2 and 4.

Tolerability of LDX was assessed by the side-effects item of the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM),29 administered weekly from week 1, and at follow-up.

Regimen completion was defined as the proportion of participants enrolled who completed the escalation phase to the end of week 4, at which point they would have received at least 5 days of 250 mg of LDX.

Secondary outcomes were: efficacy measures; change in other substance use; medication acceptability; potential for non-prescription use; adherence and neurocognitive functioning. Efficacy measures comprised changes in MA use (self-reported and urine screen), withdrawal, craving, severity of dependence, HIV transmission risk and criminal behaviours as well as participant-reported effectiveness measures. MA and other substance use was recorded weekly with a validated self-report tool, the Time Line Follow Back Questionnaire.30 31 Urine samples were obtained weekly, and tested for the presence of MA. Craving and withdrawal were measured weekly from Baseline and at Follow-up. Craving was measured with a single item 0–100 Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)32 and withdrawal with the Amphetamine Withdrawal Scale.33 Severity of dependence was measured with the Severity of Dependence Scale34 at Baseline, week 8 and follow-up. The HIV risk behaviour and crime sections of the Opiate Treatment Index35 were completed at baseline, weeks 4 and 8, and at follow-up. The TSQM Questionnaire29 was administered weekly from week 1 and at Follow-up to measure self-rated medication effectiveness, convenience and global satisfaction. Potential for non-prescription drug use was measured weekly from baseline to week 4 using the Drug Effects Questionnaire 5 (DEQ5),36 the Acute Subjective Response to Substances questionnaire for amphetamines,37 a VAS to measure similarity to MA, and asking participants what price they would pay for the drug (PWP).38

General cognition was assessed using the Wechsler test of adult reading39 and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment40 at Baseline. Paper-based neurocognitive tests were administered at baseline, week 2, week 4 and at follow-up 4 weeks after drug discontinuation assessing switching (Trail making test41 42), working memory (Digit-sequencing43) and verbal learning and memory (Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Task, RAVLT44). Electronic neurocognitive testing was conducted using the Penscreen Six software45 on an Android 7 tablet assessing: processing speed (Digit-symbol test43), sustained attention (Rapid Visual Information Processing, RVIP), attention/focus (Arrow flankers46) and inhibition (go/no-go46) weekly from Baseline until week 4 and at follow-up.47

Statistical analysis

Adverse events were described by the proportion of participants who experienced TEAE by type, severity and dose. Non-parametric tests of paired data (Wilcoxon signed rank test) were performed for measures taken at the beginning of week 1 (baseline), and compared with those taken at the primary endpoint, the end of week 4 (at presumed steady state of 250 mg/day of LDX). Mixed models for repeated measures (MMRM) were performed for primary cardiovascular (SBP, DBP and heart rate) and neurocognitive outcomes. MMRM analyses makes use of all available data and is reliable for effect estimates under missing at random assumption. The secondary outcomes of dose adequacy, medication acceptability and potential for non-prescription use are described using median scores and IQRs at each dose. Missing urine drug results are assumed positive for MA. As per protocol, change in days of MA use were analysed separately for participants who partook in at least four sessions of counselling over the 8-week trial period. Other secondary outcomes were tested for statistical significance with Wilcoxon rank-sum test for non-parametric data.

Results

Study sample

Of the 68 potential participants prescreened for the study, 16 were enrolled and commenced on the LDX regimen (figure 1) between June 2015 and December 2016. Mean age of the 16 participants was 41 years (SD 6.7), and 75.0% (n=12) were male. Participants had a mean of 12 years (SD 8.4) problematic MA use and had used MA a mean of 21 days (SD 5.4) of the previous 28. Other sample demographics at study enrolment are provided in table 1.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics at enrolment

| Demographics | All (n=16) n (% (unless otherwise indicated)) |

| Mean age (SD) | 41 (6.7) |

| Gender | |

| Cis-male | 12 (75.0) |

| Cis-female | 4 (25.0) |

| Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander | 2 (12.5) |

| Sexual Identity | |

| Heterosexual | 9 (56.3) |

| Gay or lesbian | 3 (18.8) |

| Bisexual | 3 (18.8) |

| Something else | 1 (6.3) |

| Medical history | |

| HIV infection | 3 (18.8) |

| Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection | 5 (31.3) |

| Self-reported history of childhood ADHD diagnosis | 2 (12.5) |

| Wender Utah Rating Scale* >46 | 7 (43.8) |

| Current opioid agonist therapy | 2 (12.5) |

| Concomitant psychiatric medication | 2 (12.5) |

| Other substance use (prior 28 days) | |

| Tobacco | 10 (62.5) |

| Cannabis | 5 (31.3) |

| Gamma hydroxybutyrate (GHB) | 4 (25.0) |

| Alcohol | 3 (18.8) |

| Opioids (oxycodone/heroin) | 2 (12.5) |

| Methamphetamine use | Mean (SD) |

| Age at first use (years) | 22 (9.0) |

| Years of self-reported problematic use | 12 (8.4) |

| Days use of previous 28 | 21 (5.4) |

| Reported injecting MA in past 28 days n (%) | 12 (69.0) |

| Neurocognition | Mean (SD) |

| Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) | 26 (2.6) |

| MoCA <26, n (%) | 8 (50.0) |

| Wechser Test of Adult Reading (Estimated Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale -III IQ) | 105 (11.4) |

*Score >46 considered positive for the retrospective assessment of the presence of symptoms of ADHD in childhood

ADHD, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; MA, methamphetamine.

Primary outcomes

Regimen completion

Fourteen (87.5%) participants achieved each of the doses of 100 mg, 150 mg, 200 mg and the primary endpoint of 250 mg at the end of 4 weeks. Ten participants (62.5%) completed 8 weeks of study drug and 12 (75.0%) were followed up 4 weeks after the last dose.

Two participants (12.5%) withdrew prior to the primary endpoint at the end of Week 4. One participant stopped presenting to the clinic after 5 days of 100 mg LDX in week 1. The participant declined to attend for further follow-up but responded by text message: ‘I’m OK pills made me angry and not nice feeling don’t won’t [sic] to continue’. The other participant withdrew in week 1 due to relocation away from study site.

Four participants (25.0%) were withdrawn due to non-adherence (missing three doses in a 5-day period after the escalation regimen was completed) after reaching the primary endpoint but prior to study completion: one (6.3%) in week 6 (at the 200 mg dose); two (12.5%) in week 7 (150 mg dose) and one (6.3%) in week 8 (100mg dose) (see figure 1).

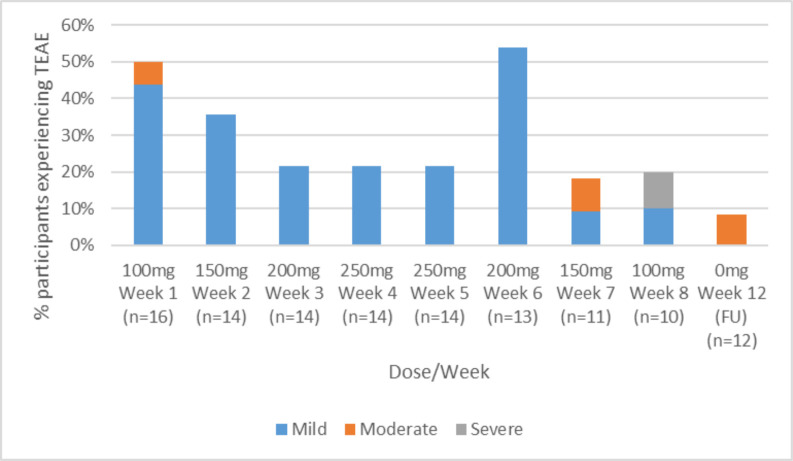

Adverse events

No participant was withdrawn due to TEAEs. The proportion of participants experiencing TEAEs by dose, week and severity are shown in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Proportion of participants experiencing adverse events by dose, week, and severity. TEAE, treatment emergent adverse event.

Daily measurements of tympanic temperature were within normal range. There was one (6.3%) SAE of suicidal ideation requiring hospitalisation, deemed possibly study drug related and classified as severe. This SAE occurred on the final day of the de-escalation regimen. The participant had a prior history of self-harm, which had not been disclosed during screening. The SAE resolved following a 7-day admission in a short stay psychiatric emergency care centre during which time atomoxetine was commenced. There were three moderate TEAEs (18.8% of participants who received at least one dose of study drug): irritability (week 1, 100 mg); viral respiratory illness (week 7, 150 mg de-escalation phase) and an episode of hypomania during the follow-up period (4 weeks after LDX cessation). All were determined to be possibly study related. An additional eight (50.0%) participants experienced at least one mild TEAE. TEAEs occurring in at least two participants throughout the 12-week study are shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Adverse events reported by at least two participants at any time (baseline to week 12)

| Adverse event category | n (%) |

| Agitation/irritability | 4* (25.0) |

| Cardiovascular | 2 (12.5) |

| Gastrointestinal | 4 (25.0) |

| Headache | 3 (18.8) |

| Loss of appetite | 2 (12.5) |

| Muscular tension/jaw clenching | 3 (18.8) |

| Pain | 3 (18.8) |

| Psychiatric | 2† (12.5) |

| Respiratory complaints | 3 (18.8) |

| Skin/soft tissue/mucosal infections | 5 (31.3) |

| Sleep disturbances | 2 (12.5) |

n=number of people reporting AE, %=of total sample (n=16).

*Including one participant in Week one who was subsequently withdrawn due to lack of adherence to protocol (missed three doses).

†Including one participant meeting definition of a serious adverse event (admission to hospital).

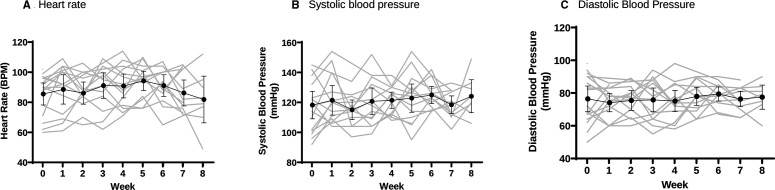

No clinically significant hostility or psychosis was detected using the relevant BPRS items.24 No participant met the study protocol discontinuation parameters for elevated SBP or experienced a treatment-limiting adverse cardiovascular event. One participant had a single DBP reading of 101 mm Hg and heart rate of 134 bpm after 5 days of 100 mg LDX. Another participant had a single pulse reading of 124 bpm during week 3 (after 5 days of 200 mg LDX), assessed to be not clinically significant. Participants’ mean change in SBP over the escalation regimen (baseline to end of week 4) was +3.4 mm Hg (range −21.0 to +27.0, SD 14.6), mean change in DBP was −0.4 mm Hg (range −22.0 to +24.0, SD 14.5), and mean change in heart rate was 7.3 bpm (range −17.0 to +37.0, SD 13.4). Individual-level change for cardiovascular outcomes are shown in figure 3. No clinically significant ECG changes were detected at week 4 following dose escalation to 250 mg.

Figure 3.

Change in cardiovascular parameters. Grey: individual measures; black—mean; error bars—95% CI. BPM, beats per minute.

Post hoc analysis did not detect significant correlation between frequency of MA use on enrolment and change in blood pressure (SBP: r=0.04, p=0.88; DBP: r=0.16, p=0.57). MMRM demonstrated no significant overall difference across the five time-points in either SBP (F4 39 =1.43, p=0.241), DBP (F4 35 =0.07, p=0.990) or HR (F4 35 =1.30, p=0.288), all measured at peak LDX concentrations (4 hours postdose) over the course of the escalation regimen, the multiple comparison of each post-baseline measure vs baseline are summarised in table 3.

Table 3.

Cardiovascular safety parameters (n=16)

| BL to week 1: estimate (SE) p value* | BL to week 2: estimate (SE) p value* | BL to week 3: estimate (SE) p value* | BL to week 4: estimate (SE) p value* | |

| Unadjusted | ||||

| SBP (4 hours postdose) | 5.5 (3.4) p=0.00.370 | −1.6 (3.5) p=0.985 | 2.7 (3.6) p=0.919 | 3.3 (3.8) p=0.853 |

| DBP (4 hours postdose) | −0.8 (2.9) p=0.998 | 0.9 (3.1) p=0.998 | 0.1 (3.1) p=1 | −0.7 (3.4) p=0.999 |

| HR (4 hours postdose) | 4.2 (2.9) p=0.497 | 3.0 (3.1) p=0.810 | 6.6 (3.1) p=0.162 | 6.2 (3.4) p=0.271 |

| Adjusted (for: age; sex at birth; baseline methamphetamine use (days)) | ||||

| SBP (4 hours postdose) | 5.8 (3.4) p=0.321 | −1.7 (3.5) p=0.981 | 2.5 (3.5) p=0.928 | 3.2 (3.7) p=0.863 |

| DBP (4 hours postdose) | −0.3 (2.9) p=1 | 0.3 (3.1) p=1 | −0.5 (3.1) p=1 | −1.4 (3.4) p=0.990 |

| HR (4 hours postdose) | 4.1 (2.9) p=0.514 | 2.9 (3.1) p=0.817 | 6.6 (3.1) p=0.165 | 6.2 (3.4) p=0.271 |

All analyses use mixed models for repeated measures.

*Sidak correction for multiple comparisons (four pairs) applied.

BL, baseline; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Study drug tolerability

Participant-rated treatment tolerability of LDX using the TSQM side effects item29 was high, with no significant difference detected (z=−0.639, p=0.524) between the lowest dose at week 1 and the highest escalated dose at the end of week 4 (table 4).

Table 4.

Outcomes

| All enrolled (n=16) |

Completed week 4 (n=14) | Completed week 4 (n=14) | Mean difference (95%CI) | P value* | Completed week 8 (n=10) |

Followed up week 12 (n=12) |

|

| Baseline | Baseline | Week 4 | |||||

| Primary outcomes | |||||||

| SBP mm Hg (median (IQR]) | 119 (101–136) | 119 (103–130) | 123 (112–130) | 3.4 (-5.0 to 11.9) | 0.327 | 124 (118–130) | 129 (106–131) |

| DBP mm Hg (median (IQR)) | 77 (65–90) | 77 (65–89) | 74 (67–85) | −0.4 (-8.8 to 8.0) | 0.975 | 78 (76–82) | 80 (72–83) |

| Heart rate bpm (median (IQR)) | 90 (76–96) | 89 (73–93) | 90 (76–103) | 7.3 (-0.4 to 15.0) | 0.059 | 81 (75–91) | 82 (77–83) |

| Weight (kg) (median (IQR)) | 73 (68–82) | 73 (68–76) | 74 (69–83) | 0.9 (0.1 to 1.8) | 0.024 | – | 73 (67–80) |

| Insomnia (ISI) (median (IQR)) | 11 (5–15) | 10 (5–13) | 7 (3–9) | −3.3 (-6.0 to 0.5) | 0.027 | 9 (1–14) | 7 (3–10) |

| Physical health (PHQ15) (median (IQR)) | 8 (5–10) | 7 (5–9) | 6 (3–8) | −2.1 (-3.2 to -0.9) | 0.004 | 7 (3–10) | 5 (2–9) |

| Depression (PHQ9) (median (IQR)) | 11 (7–14) | 11 (7–14) | 4 (3–9) | −4.6 (-7.0 to -2.1) | 0.002 | 8 (6–10) | 9 (8–11) |

| Anxiety (GAD7) (median (IQR)) | 9 (5–11) | 9 (5–10) | 4 (1–9) | −3.9 (-7.3 to -0.6) | 0.009 | 6 (1–8) | 7 (4–10) |

| TSQM—tolerability (median (IQR)) | 100 (86–100) | 100 (88–100) | 100 (98–100) | 2.4 (-5.2 to 10.0) | 0.524 | 100 (84–100) | 100 (89–100) |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||||

| Methamphetamine use (days out of last 28) (median (IQR)) | 21 (16–23) | 21 (18–26) | 13 (11–17) | 0.013 | 11 (2–13) | 13 (9–19) | |

| Urine drug screen for MA (n (%) negative) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – | – | 3 (18.8%) | 1 (6.3%) |

| Cravings (VAS) (median (IQR)) | 64 (20–85) | 64 (23–82) | 31 (12–52) | −25.9 (-47.3 to -4.6) | 0.035 | 40 (22–67) | 42 (22–87) |

| Withdrawal (AWQ) (median (IQR)) | 16 (9–18) | 16 (10–18) | 12 (7–18) | −1.4 (-4.5 to 1.8) | 0.307 | 9 (7–22) | 13 (11–20) |

| Medication efficacy (TSQM) (median (IQR)) | 50 (37–68)† | 50 (39–67)† | 64 (50–79) | 12.4 (3.8 to 21.0) | 0.021 | 69 (58–82) | 80 (63–83) |

| Medication convenience (TSQM) (median (IQR)) | 78 (61–83)† | 78 (67–83)† | 83 (56–100) | 0.2 (-9.4 to 9.7) | 0.608 | 78 (63–83) | 61 (56–78) |

| Medication global satisfaction (TSQM) (Median (IQR)) | 64 (48–87)† | 64 (50–86)† | 71(63-88) | 7.6 (-0.9 to 16.2) | 0.073 | 75 (66–79) | 79 (71–100) |

| Crime (OTI) (median (IQR)) | 2 (0–5) | 3 (0–7) | 0 (0–2) | −1.7 (-3.3 to 0.0) | 0.042 | – | 0 (0–0) |

| HIV risk behaviour (OTI) (median (IQR)) | 11 (7–14) | 10 (7–12) | 9 (5–14) | −1.2 (-3.7 to 1.3) | 0.327 | – | 10 (8–17) |

| Severity of Dependence Scale (median (IQR)) | 11 (8–12) | 11 (8–12) | – | −0.3 (-1.6 to 1.0) | – | 11 (10–12) | 11 (9–12) |

| Drug liking | |||||||

| Price Would Pay ($A) (median (IQR)) | 8 (0–33) | 5 (0–20) | 5 (0–30) | 13.8 (−17.1 to 44.7) | 0.416 | – | – |

| ASRS (median (IQR)) | 3 (2–7) | 3 (3–7) | 3 (3–7) | 0.1 (−1.7 to 1.9) | 0.811 | ||

| Similarity to MA (median (IQR)) | 22 (8–52) | 17 (8–45) | 20 (5–57) | 10.5 (−11.3 to 32.2) | 0.241 | – | – |

| DEQ5 ‘Feel’ item (median (IQR)) | 15 (8–46) | 15 (7–46) | 26 (13–45) | 9.5 (−2.3 to 21.4) | 0.221 | – | – |

| DEQ5 ‘More’ item (median (IQR)) | 48 (17–85) | 48 (13–80) | 49 (9–86) | −3.5 (−30.8 to 23.9) | 0.421 | – | – |

| DEQ5 ‘High’ item (median (IQR)) | 9 (2–35) | 9 (2–24) | 28 (5–48) | 13.5 (3.4 to 23.6) | 0.009 | – | – |

| DEQ5 ‘Like’ item (median (IQR)) | 40 (11–58) | 40 (11–45) | 47 (20–62) | 14.7 (−4.9 to 34.3) | 0.208 | – | – |

| DEQ5 ‘Dislike’ item (median (IQR)) | 4 (0–12) | 5 (1–12) | 2 (2–28) | 6.5 (−9.5 to 22.6) | 0.916 | – | – |

*Based on Wilcoxon signed-rank test; bold values denote statistical significance at the p <0.05 level.

†Measured at week 1.

ASRS, Acute Subjective Response to Substances; AWS, Amphetamine Withdrawal Scale; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DEQ 5, Drug Effects Questionnaire 5; GAD 7, Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index; MA, methamphetamine; OTI, Opiate Treatment Index; PHQ9, Patient Health Questionnaire 9; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TSQM, Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

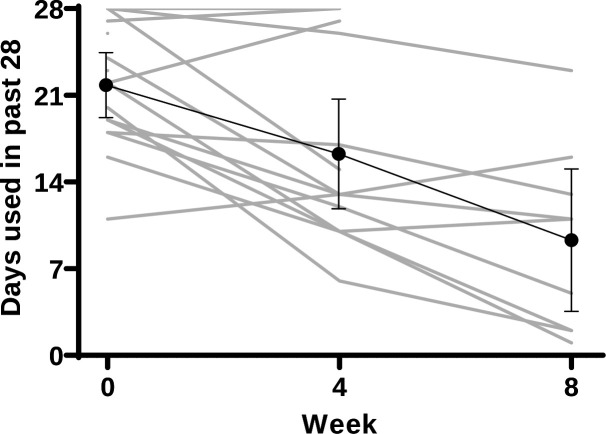

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes are provided in table 4. Days of MA use decreased significantly over the 4 weeks escalation regimen from a median of 21 (IQR: 16–23) to 13 days (IQR: 11–17) of the previous 28 days (z=−2.485, p=0.013). Individual level data of MA use are given in figure 4.

Figure 4.

Change in days of methamphetamine use. Grey: individual measures; black—mean; error bars—95% CI.

Participants who had attended four or more sessions of counselling (n=9) during the 8-week period had a mean decrease of 5.8 days (95% CI: −10.8 to −0.7, p=0.038). Those who attended fewer than four sessions (n=7), had a mean decrease of 4.0 days (95% CI:−11 to 3, p=0.144). All urine drug screens provided during the escalation phase (weeks 1–4) were positive for MA. A post hoc analysis showed three participants achieved two consecutive weeks of self-reported abstinence during the 8 weeks of LDX administration. There was a significant decrease in craving from a median of 64 mm (IQR: 20–85) to 31 mm (z=−2.105, p=0.035) on a VAS. Five (36%) of the participants reported slight increase in the frequency of other substance use over the 4 weeks (alcohol, tobacco, gamma-hydroxybutyrate, heroin), with four (29%) of these having a concurrent reduction in MA use. Self-reported medication efficacy using the TSQM was rated significantly higher at the end of week 4 than at week 1 (z=−2.301, p=0.021). Adherence to study medication was maintained from week 2 to week 5, with no participants missing more than 2 days of study medication in a 7-day period. There was an indication of improvement among participants in sleep quality, physical and mental health measures, and weight over the 4-week period. The ‘high’ item of the DEQ-5 questionnaire increased from a median score of 9 (IQR: 2–35) to 28 (IQR: 5–48) (z=−2.622, p=0.009). Other non-significant changes are reported in table 4.

All analyses use MMRM; Adjusted for: sex at birth; Wender-Utah ADHD score; WTAR performance and baseline days MA use; RAVLT % retained is RAVLT Trial 6 (delay) as a proportion of words recalled at Trial 5.

Large magnitude improvements in focused attention (Hedges’ g=1.59 at peak dose) and inhibitory control (Hedges’ g=1.12 at peak dose) were seen over the course of the trial and were maximal at 200 mg and above. Moderate magnitude but non-significant improvements were apparent on measures of processing speed and sustained attention (Hedges’ g>0.6 at peak dose for Digit Symbol, Trails A, RVIP). No meaningful changes were observed in working memory, learning, retention and switching (Hedges’ g<0.4 at peak for all) (table 5).

Table 5.

Cognitive effects of lisdexamfetamine (n=16)

| Domain | Measure | Overall effect | BL to 100 mg: Estimate (SE) Sidak-adj p value |

BL to 150 mg: Estimate (SE) Sidak-adj p value |

BL to 200 mg: Estimate (SE) Sidak-adj p value |

BL to 250 mg: Estimate (SE) Sidak-adj p value |

BL to FU: estimate (SE) Sidak-adj p value |

| Unadjusted | |||||||

| Processing speed | Trail making test (A) | F(3, 11)=4.80, p=0.022 | 1.8 (1.9) p=0.931 | 6.4 (1.9) p=0.017 | 3.8 (2.4) p=0.577 | ||

| Processing speed | Digit symbol RT | F(5, 16)=3.43, p=0.026 | 237.3 (135.8) p=0.795 | 366.1 (150.4) p=0.300 | 313.6 (137.5) p=0.425 | 345.0 (136.7) p=0.289 | 317.9 (140.0) p=0.423 |

| Attention | Flankers RT | F(5, 38)=9.07, p<0.001 | 27.8 (13.5) p=0.496 | 44.4 (14.0) p=0.035 | 50.1 (12.5) p=0.010 | 58.3 (12.5) p<0.001 | 16.6 (17.1) p=0.998 |

| Attention | Flankers Per cent Correct | F(5, 29)=2.18, p=0.084 | 0.5 (0.2) p=0.188 | 0.2 (0.3) p=0.999 | 0.5 (0.2) p=0.085 | 0.3 (0.2) p=0.768 | 0.2 (0.3) p=0.999 |

| Sustained attention | RVIP Reaction Time (RT) | F(5, 16)=3.26, p=0.032 | 28.3 (25.5) p=0.992 | 70.1 (19.5) p=0.031 | 58.9 (22.2) p=0.189 | 60.7 (18.1) p=0.058 | 73.3 (25.2) p=0.153 |

| Sustained attention | RVIP Per cent Correct | F(5, 14)=5.42, p=0.011 | 0.4 (1.2) p=0.999 | 3.2 (1.0) p=0.061 | 3.9 (1.1) p=0.019 | 2.8 (1.2) p=0.332 | 2.9 (1.2) p=0.262 |

| Working memory | Digit Sequencing Span | F(3, 12)=1.79, p=0.202 | 1.2 (0.6) p=0.377 | 0.3 (0.5) p=0.980 | 0.9 (0.5) p=0.510 | ||

| Immediate memory | RAVLT Trial 1 | F(3, 11)=0.55, p=0.660 | 0.3 (0.6) p=0.998 | 0.6 (0.5) p=0.791 | 0.5 (0.6) p=0.978 | ||

| Learning | RAVLT Trials 1–5 | F(3,13)=3.01, p=0.068 | 4.1 (3.2) p=0.783 | 1.9 (3.1) p=0.990 | 7.0 (2.4) p=0.125 | ||

| Retention | RAVLT % Retained | F(3, 18)=0.52, p=0.677 | −0.6 (10.3) p=0.999 | 4.3 (8.5) p=0.997 | −4.4 (10.6) p=0.999 | ||

| Switching | Trail making test (B) | F(3, 13)=5.18, p=0.015 | 5.2 (8.9) p=0.993 | 7.9 (7.6) p=0.892 | 18.0 (6.2) p=0.029 | ||

| Inhibition | Go-NoGo False Positives | F(5, 21)=6.53, p=0.001 | 2.3 (0.6) p=0.015 | 2.4 (0.7) p=0.016 | 2.6 (0.9) p=0.097 | 2.9 (0.5) p=0.001 | 3.0 (0.6) p=0.001 |

| Adjusted | |||||||

| Processing speed | Trail making test (A) | F(3,10)=2.91 p=0.090 | 0.1 (2.4) p=0.999 | 5.6 (2.6) p=0.240 | 4.2 (3.5) p=0.840 | ||

| Processing speed | Digit Symbol RT | F(5, 12)=2.08 p=0.141 | 322.5 (157.3) p=0.599 | 414.7 (177.6) p=0.362 | 383.9 (163.1) p=0.382 | 383.9 (163.1) p=0.263 | 394.7 (169.0) p=0.399 |

| Attention | Flankers RT | F(5, 40)=9.13 p<0.001 | 34.3 (14.0) p=0.227 | 51.3 (14.7) p=0.013 | 60.5 (15.3) p=0.002 | 68.8 (13.9), p<0.001 | 24.1 (18.0) p=0.956 |

| Attention | Flankers Per cent Correct | F(5, 30)=1.22 p=0.323 | 0.3 (0.2) p=0.727 | 0.1 (0.3) p=0.999 | 0.3 (0.2) p=0.863 | 0.1 (0.2) p=0.999 | 0.1 (0.3) p=0.999 |

| Sustained attention | RVIP RT | F(5, 15)=2.07 p=0.125 | 10.2 (30.7) p=0.999 | 54.6 (24.2) p=0.431 | 48.6 (31.0) p=0.876 | 48.3 (24.5) p=0.631 | 23.2 (25.6) p=0.999 |

| Sustained attention | RVIP Per cent Correct | F(5, 11)=2.37 p=0.105 | −0.1 (1.5) p=0.932 | 2.6 (1.3) p=0.055 | 3.4 (1.4) p=0.025 | 2.9 (1.6) p=0.081 | 2.6 (1.7) p=0.131 |

| Working memory | Digit Sequencing Span | F(3, 11)=0.93 p=0.461 | 1.3 (0.8) p=0.517 | 0.5 (0.6) p=0.970 | 0.4 (0.8) p=0.998 | ||

| Immediate memory | RAVLT Trial 1 | F(3, 9)=0.87 p=0.872 | 0.2 (0.8) p=0.999 | 0.2 (0.6) p=0.999 | 0.7 (0.9) p=0.969 | ||

| Learning | RAVLT Trials 1–5 | F(3, 13)=4.46 p=0.024 | 5.9 (4.3) p=0.722 | 3.0 (4.2) p=0.982 | 11.2 (3.1) p=0.088 | ||

| Retention | RAVLT % Retained | F(3, 13)=0.03 p=0.994 | −2.9 (12.3) p=0.999 | −0.7 (9.9) p=0.999 | 0.5 (13.9) p=0.999 | ||

| Switching | Trail making test (B) | F(3, 14)=2.97 p=0.067 | 8.1 (10.8) p=0.976 | 16.2 (9.5) p=0.486 |

22.2 (7.9) p=0.068 |

||

| Inhibition | Go-NoGo False Positives | F(5, 18)=5.04 p=0.005 | 2.1 (0.7) p=0.114 | 1.6 (0.8) p=0.579 | 2.9 (1.1) p=0.208 | 2.8 (0.7), p=0.010 | 3.1 (0.7) p=0.008 |

Bold values denote statistical significance at the p<0.05 level.

Discussion

Principal findings and comparison with other studies

We found that dose escalation of LDX over 4 weeks to a maximum of 250 mg/day appeared to be safe in people who use MA frequently (at least 14 out of the previous 28 days).

The physiological effects of LDX were not treatment-limiting in this sample. Cardiovascular changes were mild, with no significant change in blood pressure, and similarly mild (though trending towards significant) changes in heart rate at the completion of the escalation to 250 mg. This contrasts with a study among stimulant-naive populations where single sequential doses up to 250 mg per day observed dose-dependent adverse changes in blood pressure, with more than half of their participants (11 of 20) withdrawn due to meeting blood pressure endpoints.17 These findings were not observed in a study of up to 250 mg LDX daily among people with stable schizophrenia treated with antipsychotic medication, which may attenuate the pressor effects of LDX.19 In our study, tolerance to the pressor effects may result from chronic stimulant exposure among MA dependent participants,48 though the small study sample prevents any conclusions on inverse correlation between frequency of MA use prior to enrolment and change in blood pressure.

One SAE was reported by a participant, suicidal ideation on the last day of the 8 weeks LDX administration period, which required hospitalisation. One participant withdrew from the study due to feelings of anger and hostility. This occurred at the lowest dose (100 mg) during week 1, likely related to the drug rather than to the dose. While no clinically significant results were obtained with the BPRS, these events suggest it would be prudent to closely monitor patients’ mental state receiving higher doses of LDX, as well as comprehensive treatment planning when the drug is ceased. The slight increase in other substance use over the escalation period suggests that this should also be monitored during periods of LDX administration.

Other TEAEs reported during the study likely to be drug related were known side effects of LDX (agitation, headache, loose stool, decreased appetite and jaw clenching). Other measures of general health (weight, PHQ-15, PHQ-9, GAD-7) either improved or showed no deterioration, and participant subjective rating of side effects (TSQM-side effects) show high participant tolerability of LDX at all doses. These findings support the feasibility and acceptability of LDX as a possible pharmacotherapy for MA dependence.

A reduction in self-reported MA use was significantly associated with LDX administration, indicating possible efficacy as a treatment for MA dependence. In addition, three participants achieved two consecutive weeks of self-reported MA cessation by the end of the 8 weeks of LDX administration. There was also a significant decrease in MA craving, as well as subjective rating of drug efficacy, supporting the utility of larger trials of LDX for this population. Although the reimbursement may have contributed an incentivising effect, the high proportion of participants (n=14 (87.5%)) to complete the protocol to the highest dose is promising, given typically low recruitment and retention in studies among this population.8

LDX is theorised to have lower propensity for non-prescription use, having a slower onset of action than similar agonist formulations such as dexamphetamine and methylphenidate.49 50 Studies show lower drug-liking for LDX compared with other stimulant medications for doses up to 100 mg.51 In this study, the DEQ-5 item ‘Do you feel high?’, increased from 9 mm at baseline but remained low at 29 mm at 250 mg/day LDX on a 100 mm VAS, a clinically insignificant finding. PWP remained consistent at AUD $5 across dose ranges, and other changes in the drug liking effects were not significant. This indicates that LDX may have less potential for non-prescription use than other candidate agonists. Concurrent use of other substances should also be monitored in future trials of LDX, given that a small increase in other substance use was noted by participants.

Neurocognitive data showed no safety concerns and promising efficacy signals. Although interpretation is necessarily limited by the lack of a comparison group, there were moderate to large magnitude improvements in processing speed, focused attention, sustained attention and inhibitory control. No meaningful changes in measures of working memory, learning, retention and switching were seen. General improvements on speeded tasks may be due to the stimulant effects of LDX, as improvements were dose dependent. The improvement of both speed and accuracy may reflect task learning due to repeated administration of neurocognitive assessments; and/or stabilisation of cognitive performance with chronic/tonic stimulant use compared with phasic/intermittent illicit stimulant use, (most participants continued illicit stimulant use throughout). Should LDX enhance cognition, this may have additional benefits in treatment adherence and functional outcomes. Task learning effects and associations between cognition and functional outcomes can be assessed in randomised controlled trial settings.

Limitations of the study

The small sample size and short duration of treatment is typical of pilot safety studies; but the study is not powered to explore efficacy and this precludes more sophisticated statistical analysis. The lack of a control group also limits generalisability of secondary efficacy measures. Though blinded to dose escalation, the study was open label and so the participants may be subject to expectation effects. The maximum dose tested with the protocol was chosen on the basis of equivalence of doses of dexamphetamine used in agonist maintenance therapy in this population.16 Although we tested 250 mg, this was not dose-limiting. Higher rates of MA cessation could be obtained by a period of longer than 2 weeks at the highest dose of 250 mg LDX; and higher doses could be explored.

Future research

Further studies of longer duration with larger sample sizes are required. Our group is currently conducting a multicentre, randomised, controlled trial to assess efficacy (ACTRN12617000657325).52

For people with MA dependence, this study is the first to demonstrate the safety, tolerability and acceptability of higher doses of LDX than used for ADHD. Findings suggest the feasibility of larger scale studies to determine the efficacy of LDX for this indication.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the study participants. We would like to thank Duncan Graham, medical writer, for support in editing and finalising the manuscript. We would also thank the study nurses and research assistants involved (Elaine Murray and Melissa Jackson at HNELHD, and Tamara Gradden and Alex Bissaker at SVHS), the nursing and counselling staff at each of the clinical sites, Robyn Richardson at SVHS for her assistance with the protocol and Michelle Hall for project management at HNELHD.

Footnotes

Contributors: NE, BC, AD, RB, AC, KJS and NL designed the study. NE, BC and KJS drafted the manuscript. BC and ZL undertook statistical analyses. NE and AD were site leads. All authors critically revised and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was undertaken with the support of: the St Vincent’s Curran Foundation, Sydney; St. Vincent’s Hospital, Sydney; and Hunter New England Local Health District.

Competing interests: NE and AC are employed by St Vincent’s Hospital Sydney, a public health service funded by the NSW Ministry of Health. BC is employed by St Vincent’s Health Australia and has no conflicts to declare. AD is employed by Hunter New England Local Health District, a public health service funded by NSW Health and reports research and travel support from Braeburn/Camurus, research support from Indivior, and has served on an advisory board for Mundipharma, all for unrelated work. RB has received investigator-initiated untied educational grants from Reckitt Benckiser/Indivior for the development of an opioid-related behaviour scale and a study of opioid substitution therapy uptake among chronic non-cancer pain patients. RB has received an untied educational grant from Mundipharma for a postmarketing study of reformulated oxycodone. AC has received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, and ViiV Healthcare; lecture and travel sponsorships from Gilead Sciences and ViiV Healthcare; and has served on advisory boards for Gilead Sciences, MSD and ViiV Healthcare, all of which are unrelated to this present study. ZL is employed by UNSW and has no competing interests to declare. KJS is employed by UNSW and has received unrelated travel sponsorship from Gilead Sciences. NL is employed by South East Sydney Local Health District, a public health service funded by the NSW Ministry of Health; he has received research funding from Camurus, and has served on Advisory Boards for Mundipharma, Camurus and Indivior for work unrelated to this study.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the small sample size but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was granted by the St Vincent’s Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee for both study sites (HREC/14/SVH/202).

References

- 1.United Nationa Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) . World drug report 2019 (United nations publication, sales No. E.19.XI.8. Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farrell M, Martin NK, Stockings E, et al. Responding to global stimulant use: challenges and opportunities. Lancet 2019;394:1652–67. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32230-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hillhouse MP, Marinelli-Casey P, Gonzales R, et al. Predicting in-treatment performance and post-treatment outcomes in methamphetamine users. Addiction 2007;102 Suppl 1:84–95. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01768.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darke S, Kaye S, McKetin R, et al. Major physical and psychological harms of methamphetamine use. Drug Alcohol Rev 2008;27:253–62. 10.1080/09595230801923702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colfax G, Santos G-M, Chu P, et al. Amphetamine-group substances and HIV. Lancet 2010;376:458–74. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60753-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee NK, Rawson RA. A systematic review of cognitive and behavioural therapies for methamphetamine dependence. Drug Alcohol Rev 2008;27:309–17. 10.1080/09595230801919494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker A, Boggs TG, Lewin TJ. Randomized controlled trial of brief cognitive-behavioural interventions among regular users of amphetamine. Addiction 2001;96:1279–87. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96912797.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siefried KJ, Acheson LS, Lintzeris N, et al. Pharmacological treatment of methamphetamine/amphetamine dependence: a systematic review. CNS Drugs 2020;34:337–65. 10.1007/s40263-020-00711-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perez-Mana C, Castells X, Torrens M. Efficacy of psychostimulant drugs for amphetamine abuse or dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;CD009695. 10.1002/14651858.CD009695.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herin DV, Rush CR, Grabowski J. Agonist-Like pharmacotherapy for stimulant dependence: preclinical, human laboratory, and clinical studies. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010;1187:76–100. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05145.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradbeer TM, Fleming PM, Charlton P, et al. Survey of amphetamine prescribing in England and Wales. Drug Alcohol Rev 1998;17:299–304. 10.1080/09595239800187131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Myton T, Carnwath T, Crome I. Health and psychosocial consequences associated with long-term prescription of dexamphetamine to amphetamine misusers in Wolverhampton 1985-1998. Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy 2004;11:157–66. 10.1080/09687630310001611170 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ezard N, Francis B, Brown A, et al. What do we know about dexamphetamine in the treatment of methamphetamine dependence? 8 years of the NSW stimulant treatment program in Newcastle and Sydney. Australian Drug Conference. Melbourne, Victoria, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sinita E, Coghill D. The use of stimulant medications for non-core aspects of ADHD and in other disorders. Neuropharmacology 2014;87:161–72. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heal DJ, Smith SL, Gosden J, et al. Amphetamine, past and present--a pharmacological and clinical perspective. J Psychopharmacol 2013;27:479–96. 10.1177/0269881113482532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Longo M, Wickes W, Smout M, et al. Randomized controlled trial of dexamphetamine maintenance for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Addiction 2010;105:146–54. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02717.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jasinski DR, Krishnan S. Abuse liability and safety of oral lisdexamfetamine dimesylate in individuals with a history of stimulant abuse. J Psychopharmacol 2009;23:419–27. 10.1177/0269881109103113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ermer J, Homolka R, Martin P, et al. Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate: linear dose-proportionality, low intersubject and intrasubject variability, and safety in an open-label single-dose pharmacokinetic study in healthy adult volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol 2010;50:1001–10. 10.1177/0091270009357346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin P, Dirks B, Gertsik L, et al. Safety and pharmacokinetics of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate in adults with clinically stable schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ascending multiple doses. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2014;34:682–9. 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ezard N, Dunlop A, Clifford B, et al. Study protocol: a dose-escalating, phase-2 study of oral lisdexamfetamine in adults with methamphetamine dependence. BMC Psychiatry 2016;16:428. 10.1186/s12888-016-1141-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization . The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shire Australia Pty Ltd . Product Informaton: VYVANSE® lisdexamfetamine dimesilate. Available: http://pi.shirecontent.com/PI/PDFs/Vyvanse_USA_ENG.pdf [Accessed 15 May 2020].

- 23.Krishnan SM, Stark JG. Multiple daily-dose pharmacokinetics of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate in healthy adult volunteers. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:33–40. 10.1185/030079908X242737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Overall JE, Gorham DR. The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychol Rep 1962;10:799–812. 10.2466/pr0.1962.10.3.799 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the insomnia severity index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med 2001;2:297–307. 10.1016/S1389-9457(00)00065-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–7. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med 2002;64:258–66. 10.1097/00006842-200203000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Atkinson MJ, Sinha A, Hass SL, et al. Validation of a general measure of treatment satisfaction, the treatment satisfaction questionnaire for medication (TSQM), using a national panel study of chronic disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2004;2:12. 10.1186/1477-7525-2-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow back: a calendar method for assessing alcohol and drug use (users guide). Toronto: Addiction Research Foundation, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rowe C, Vittinghoff E, Colfax G, et al. Correlates of validity of self-reported methamphetamine use among a sample of dependent adults. Subst Use Misuse 2018;53:1742–55. 10.1080/10826084.2018.1432649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee JW, Brown ES, Perantie DC, et al. A comparison of single-item visual analog scales with a multiitem likert-type scale for assessment of cocaine craving in persons with bipolar disorder. Addict Disord Their Treat 2002;1:140–2. 10.1097/00132576-200211000-00005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Srisurapanont M, Jarusuraisin N, Jittiwutikan J. Amphetamine withdrawal: I. reliability, validity and factor structure of a measure. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 1999;33:89–93. 10.1046/j.1440-1614.1999.00517.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gossop M, Darke S, Griffiths P, et al. The severity of dependence scale (SDS): psychometric properties of the SDS in English and Australian samples of heroin, cocaine and amphetamine users. Addiction 1995;90:607–14. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.9056072.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adelekan M, Green A, Dasgupta N, et al. Reliability and validity of the opiate treatment index among a sample of opioid users in the United Kingdom. Drug Alcohol Rev 1996;15:261–70. 10.1080/09595239600186001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morean ME, de Wit H, King AC, et al. The drug effects questionnaire: psychometric support across three drug types. Psychopharmacology 2013;227:177–92. 10.1007/s00213-012-2954-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin WR, Sloan JW, Sapira JD, et al. Physiologic, subjective, and behavioral effects of amphetamine, methamphetamine, ephedrine, phenmetrazine, and methylphenidate in man. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1971;12:245–58. 10.1002/cpt1971122part1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Comer SD, Zacny JP, Dworkin RH, et al. Core outcome measures for opioid abuse liability laboratory assessment studies in humans: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain 2012;153:2315–24. 10.1016/j.pain.2012.07.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wechsler D. Wechsler test of adult reading (WTAR). San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:695–9. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reitan RM. The relation of the TRAIL making test to organic brain damage. J Consult Psychol 1955;19:393–4. 10.1037/h0044509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reitan RM. Validity of the TRAIL making test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept Mot Skills 1958;8:271–6. 10.2466/pms.1958.8.3.271 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wechsler D. Wechsler adult intelligence scale: technical and interpretive manual. San Antonio: Pearson, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rey A. L’examen Clinique en psychologie [clinical psychological examination]. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cameron E, Sinclair W, Tiplady B. Validity and sensitivity of a pen computer battery of performance tests. J Psychopharmacol 2001;15:105–10. 10.1177/026988110101500207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eriksen BA, Eriksen CW. Effects of noise letters upon the identification of a target letter in a nonsearch task. Percept Psychophys 1974;16:143–9. 10.3758/BF03203267 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lovell ME, Bruno R, Johnston J, et al. Cognitive, physical, and mental health outcomes between long-term cannabis and tobacco users. Addict Behav 2018;79:178–88. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rush CR, Stoops WW, Lile JA, et al. Subjective and physiological effects of acute intranasal methamphetamine during d-amphetamine maintenance. Psychopharmacology 2011;214:665–74. 10.1007/s00213-010-2067-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rowley HL, Kulkarni R, Gosden J, et al. Lisdexamfetamine and immediate release d-amfetamine - differences in pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationships revealed by striatal microdialysis in freely-moving rats with simultaneous determination of plasma drug concentrations and locomotor activity. Neuropharmacology 2012;63:1064–74. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rowley HL, Kulkarni RS, Gosden J, et al. Differences in the neurochemical and behavioural profiles of lisdexamfetamine methylphenidate and modafinil revealed by simultaneous dual-probe microdialysis and locomotor activity measurements in freely-moving rats. J Psychopharmacol 2014;28:254–69. 10.1177/0269881113513850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jasinski DR, Krishnan S. Abuse liability and safety of oral lisdexamfetamine dimesylate in individuals with a history of stimulant abuse. J Psychopharmacol 2009;23:419–27. 10.1177/0269881109103113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ezard N, Dunlop A, Hall M, et al. Lima: a study protocol for a randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled trial of lisdexamfetamine for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020723. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the small sample size but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.