Abstract

Objective

The aim of this economic evaluation was to assess whether home management could represent a cost-effective strategy in the patient pathway of type 1 diabetes (T1D). This is based on the Delivering Early Care In Diabetes Evaluation trial (ISRCTN78114042), which compared home versus hospital management from diagnosis in childhood diabetes and found no statistically significant difference in glycaemic control at 24 months.

Design

Cost-effectiveness analysis alongside a randomised controlled trial.

Setting

Eight paediatric diabetes centres in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Participants

203 clinically well children aged under 17 years, with newly diagnosed T1D and their carers.

Outcome measures

The base-case analysis adopted n National Health Service (NHS) perspective. A scenario analysis assessed costs from a broader societal perspective. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), expressed as cost per mmol/mol reduction in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), was based on the mean difference in costs between the home and hospital groups, divided by mean differences in effectiveness (HbA1c). Uncertainty was considered in terms of the probability of cost-effectiveness.

Results

At 24 months postintervention, the base-case analysis showed a difference in costs between home and hospital, in favour of home management (mean difference −£2,217; 95% CI −£2825 to −£1,609; p<0.001). Home care dominated, with an ICER of £7434 (saved) per mmol/mol reduction of HbA1c. The results of the scenario analysis also favoured home management. The greatest driver of cost differences was hospitalisation during the initiation period.

Conclusions

Home management from diagnosis of children with T1D who are medically stable represents a less costly approach for the NHS in the UK, without impacting clinical effectiveness.

Trial registration number

Keywords: health economics, diabetes & endocrinology, paediatric endocrinology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Cost-effectiveness analysis based on a randomised controlled trial, using patient-level data on resource use, collected prospectively.

Methods were consistent with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence reference case, as recommended for the National Health Service in the UK.

Quality-adjusted life years were not used as the health outcome and therefore interpretation of cost-effectiveness is more challenging.

Cost-effectiveness was assessed over the trial period only; lifetime extrapolation was not performed to identify long-term costs and benefits.

Clinical practice has evolved since the trial commenced and consequently resource use and costs will have changed.

Introduction

A diagnosis of type 1 diabetes (T1D) poses a significant economic burden on healthcare systems, due to the resources required for effective management, the associated complications, and its life-long course. As a result, it is estimated that the National Health Service (NHS) spends £1 billion a year on T1D; 11% of this expenditure is on inpatient care.1 The cost of keeping someone in hospital is high and, as a result, there has been a growing emphasis on delivery of care within primary care and community settings.2 Patients’ attitudes are also shifting towards wanting to be more involved in their own care and wishing to be treated closer to home, as highlighted in the NHS England Five Year Forward Plan.3 Evidence suggests that initial management of T1D can be successfully delivered at home rather than in hospital4–6 although the cost-effectiveness of this approach is unknown in the UK.

T1D affects 25.1 per 100 000 children and young people in the UK and the incidence is rising.7 It is a life-long condition, which can lead to serious short (eg, diabetic ketoacidosis) and long-term (eg, renal, vascular and retinal damage) complications.8 The risk of complications is reduced if blood glucose is kept within healthy targets.9 To achieve this, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends offering children and their families intensive education on insulin management from diagnosis and a long-term package of care, delivered through a multidisciplinary team. The NICE guidelines state that the choice of where this initial care is delivered should be made based on clinical need, family circumstances and wishes.10 Hospitalisation has been shown to be a substantially stressful event for both the child and their parents11 and so should be avoided unless clinically necessary. Most children with T1D are not acutely unwell at diagnosis and therefore could be managed at home.6 12

However, there have been few, well-designed studies evaluating home versus hospital management. A Cochrane review in 2007 concluded that the results of prior studies were inconclusive but suggested that home management at diagnosis does not lead to any clinical, psychological or cost disadvantages.5 Since this review, further randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have been conducted. One was carried out in Sweden, where home management was described as ‘hospital-based home care’ as it involved staying in a facility which was designed to replicate a home environment but was located in the hospital grounds.13 There was no difference between ‘hospital-based home care’ and ‘hospital care’, in terms of glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) (mean difference between groups 0.6 mmol/mol; p=0.777) but a cost-effectiveness analysis reported significantly lower healthcare (direct) costs in the home managed group (−SEK 16 212 (−£1318); p<0.05).13

More recently, the Delivering Early Care In Diabetes Evaluation (DECIDE) RCT evaluated home vs hospital management at diagnosis in childhood diabetes.14 It was conducted between 2008 and 2013 in eight paediatric diabetes centres in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. The primary outcome was HbA1c at 24 months postdiagnosis and secondary outcomes included coping, anxiety, quality of life and use of NHS resources. The trial found no statistically significant difference in HbA1c between home and hospital management (1.01 mmol/mol, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.09) and there were no differences in secondary outcomes at 24 months, other than a higher self-esteem in children who were managed at home.

The aim of the present analysis was to estimate the cost-effectiveness of home vs hospital management of children diagnosed with T1D from the perspective of the NHS in the UK.

Methods

The DECIDE trial protocol and results are described in detail elsewhere.14 15 Briefly, DECIDE was a superiority RCT, designed to compare the clinical effectiveness of home care from diagnosis with hospital-based care in the management of T1D. The sample size needed to detect a difference in mean HbA1c of 5 mmol/mol (with an SD of 14 mmol/mol; equivalent to an effect size of 0.4) was 200 participants (100 per group) at a 5% significance level and 80% power.

Following informed consent, 203 clinically well children aged less than 17 years old with newly diagnosed diabetes, from eight paediatric diabetes centres across the UK, were randomised to home or hospital management. Participants were eligible to take part if they or their carers were deemed able to complete the study requirements and gave informed assent or consent. Participants were excluded if they were not medically stable at diagnosis or required hospitalisation for other reasons. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in the trial protocol.15 The economic evaluation considered the intention to treat population.

Study perspective

The base-case analysis of this economic evaluation follows the cost perspective of the NHS.16 Indirect costs (impact on productivity) and direct non-medical costs (incurred by the patient and his/her carer) were also evaluated through separate scenario analyses as T1D has been shown to have wider economic impacts.17

Intervention and comparator

The intervention involved management of the initiation period from diagnosis in the family’s own home, for a minimum of 3 days, to include at least six supervised injections and delivery of pragmatic educational care. This meant that children were discharged on the day of diagnosis, with no overnight stays in hospital. All subsequent management, education (diabetes and dietetic) was provided by nursing staff and dietitians either in the child’s home or as an outpatient. In comparison, participants in the hospital group were admitted to hospital on the day of diagnosis, for a minimum of 3 days and received education and support in line with local practice.

Discount rate

A discount rate of 3.5% per annum was applied to costs and consequences after 12 months, as recommended by NICE.16 We used this rate because all economic evaluations require that future costs and effects are discounted to present value to account for time preference. In the UK, the discount rate is set at 3.5% per annum.

Estimating resources and costs

Data on resource use were collected using case report forms (CRFs) at baseline, then at 3, 12 and 24 months which were summed to calculate total resource use over 24 months (online supplemental table 1). Baseline data comprised data collected from the day of diagnosis until day 3 of either home or hospital management. Resource use prior to diagnosis was not included.

bmjopen-2020-043523supp001.pdf (221.3KB, pdf)

The base-case analysis considered direct NHS resource use. This encompassed hospital stay, tests and investigations, insulin usage, nurse and dietician travel, and contacts with healthcare professionals.

Contacts with healthcare professionals, along with distance travelled, was collected with each CRF. These were costed using the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) 2019 compendium of NHS unit costs.18

The unit costs of a paediatric overnight hospital stay were sourced from the NHS Reference Costs database 2019/2020.19

Tests and investigations were costed through contacting the Biochemistry and Immunology Department within the University Hospital of Wales, the main centre for the trial. Unit costs not provided were inflated from previously supplied figures from Cwm Taf Health Board to 2019/2020 figures, using the Campbell & Cochrane Economics Methods Group - Evidence for Policy and Practice Information - Centre (CCEMG-EPPI-Centre) Cost Converter.20

Insulin regimen data were collected at all time points. This included type of insulin, number of units prescribed throughout the day and related equipment usage (at follow-up only). Medical equipment included items such as testing strips, needles and lancets. The British National Formulary for Children and the NHS Electronic Drug Tariff were used to reference insulin costs and equipment.21 22

Broader perspectives, considering non-healthcare resource use, were adopted in scenario analyses. These covered productivity losses incurred by the patient and their family (indirect costs), including days off school and work, as well as travel and out of pocket expenses (direct costs) related to managing T1D. Days taken off work were costed based on average salary earnings in the UK.23 Time taken off school was costed based on calculating an average cost spent per pupil per day, based on the Annual Report on Education Spending in England.24 Reported out of pocket expenses incurred by patients and their carers were inflated to 2019/2020 costs using the UK Consumer Price Index.25

Currency and cost year

Costs were reported in British pounds sterling for 2019/2020.

Choice of model

The results of the main DECIDE trial demonstrated no statistically significant clinical difference between home and hospital groups and therefore it was deemed that an evaluation of lifetime costs using an economic model was neither necessary nor informative.

Assumptions

The CRFs did not collect data on length of consultations with healthcare professionals and so assumptions were made based on PSSRU data and through communication with healthcare professionals. Further assumptions relating to the calculation and estimation of costs are reported in online supplemental tables 2–7.

Outcome measures and economic analysis

The primary measure of clinical effectiveness was HbA1c at 24 months. As alternative measures to enable the calculation of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) were not used in DECIDE, HbA1c was used as the measure of effect for the cost-effectiveness analysis.

The mean total costs of each scenario were calculated for both the intervention and control groups over 24 months. This follow-up period was chosen as it was expected that most participants would have no significant endogenous insulin secretion by this time point. Costs are also reported for the initiation period (0–3 days).

Cost-effectiveness was assessed through estimation of the incremental cost per unit change in HbA1c (mmol/mol). This is based on the difference in mean total cost per patient between the intervention and control group (home and hospital management), divided by the difference in mean HbA1c. The resulting incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was compared with reference to what the NHS is willing to pay (WTP) for an additional unit change in HbA1c; this being inferred from existing interventions in diabetes.

A cost–consequences analysis was conducted, in which the costs and outcomes are presented in a tabular format to support decision-makers and allow them to attach their own weighting to each result. These outcomes include measures of physical, psychological and social consequences based on parent answers about their child.

Analytical methods

Data collected were inputted into IBM SPSS V.25 for analysis.26 The data were assessed for accuracy and missing data. Any outliers identified were checked against the original CRF and then investigated through a sensitivity analysis. An analysis of randomness was carried out on missing data to compare against patients’ sociodemographic data.27 If participants left a blank response, we assumed that zero items of resources were used.

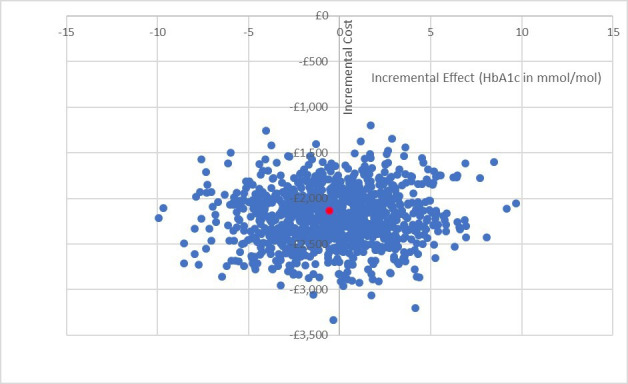

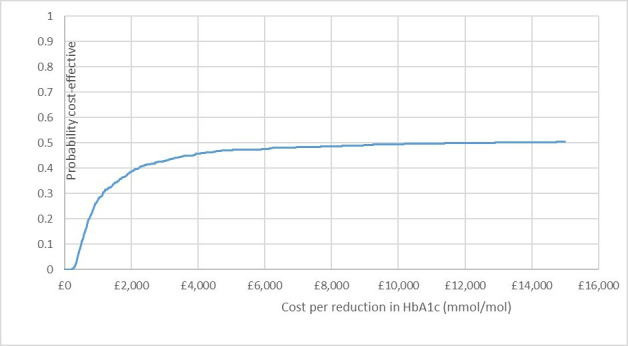

Uncertainty in the cost-effectiveness ratio was considered by use of non-parametric bootstrapping using Stata.28 This involved sampling (with replacement) pairs of mean cost and HbA1c 10 000 times as a means of estimating the sampling distribution.29 Separate regression analyses were conducted to adjust total costs (by arm and centre) and 24-month HbA1c (on arm, centre and baseline HbA1c). This produced 95% CIs for each cost variable and the differences in both costs and effect for calculating the ICER. This was done for direct healthcare costs with and without patient or carer borne costs. Microsoft Excel was then used to bootstrap HbA1c and total direct healthcare costs at 24 months (1000 replications) and results are displayed on a cost-effectiveness plane. The cost-effectiveness plane is used to visually represent the differences in costs and health outcomes between arms in two dimensions. A cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC) was drawn to represent the probability of cost-effectiveness for different values of WTP.30 This was repeated for the wider perspective, encompassing direct non-healthcare costs and indirect productivity losses. The CEAC is used to summarise the impact of uncertainty on the result of an economic evaluation. It represents the probability of an intervention being cost-effective for any given value of the cost-effectiveness threshold.

A univariate sensitivity analysis was also conducted, adjusting the cost of an overnight stay in hospital for an alternative value, to assess the impact on the ICER.

Reporting

The economic analysis of DECIDE is reported in accordance with the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards.31

Patient and public involvement

There was no direct involvement of patients or the public in this health economics study. However, two parents of children diagnosed with T1D were involved in the initial design of the DECIDE trial. One of these parents was a coapplicant on the funding application and was instrumental in ensuring that the trial was informed by the families’ experience. She also attended the ethics committee meeting to provide a service user perspective of the value of the trial to inform the committee’s decision. She and another parent were part of the Trial Management Group which met monthly and provided input on the conduct of the trial throughout.

Results

Sample

Of the 203 children involved in the trial, one participant dropped out within the first few days, eight were missing a 24-month HbA1c measurement and one patient did not have a baseline HbA1c. Therefore, the primary analysis of the clinical data reported results on the remaining 193 participants. To ensure consistency and allow for calculation of the ICER, the same participants were included in the economic analysis.

Healthcare outcomes

The DECIDE trial found no significant difference in HbA1c at 24 months between home and hospital management (72.1 mmol/mol and 72.6 mmol/mol; p=0.863, respectively). This was not affected by repeated measures or sensitivity analyses. Baseline characteristics were explored and both groups were considered to have reasonable similarities.14

Direct healthcare resource use and costs

Over 24 months, home management was less costly than hospital management (−£2217; 95% CI −£2825 to -£1609; p<0.001) (table 1). The greatest difference in direct NHS costs, in favour of home management, was seen during days 0–3 (−£2,223; 95% CI −£2373 to −£2,072; p<0.001). During this time, participants in the home management group had fewer contacts with consultants and junior doctors but more non face-to-face interactions with nurses (ie, telephone calls and email correspondence) (table 2). Overall, this led to costs during days 0–3 of £974 per child for home management and £720 for hospital management, in terms of contacts with the Diabetes Team (mean difference in cost of £254; 95% CI £147 to £361; p<0.001). The cost of nurse travel was also significantly higher for home management (mean difference £115; 95% CI £86 to £143; p<0.001). However, this increased expense was outweighed by the cost of the hospital stay in the first 3 days for those in the hospital group (£2,583; 95% CI £2464 to £2702 per child). This had the greatest contribution to the total direct healthcare costs.

Table 1.

Costs relating to resource use

| Home management (n=98), mean (95% CI) (£) | Hospital management (n=95), mean (95% CI) (£) | Difference between home and hospital, mean (95% CI) (£) | P value for difference between home and hospital | ||

| Direct healthcare costs | |||||

| Days 0–3 | Contact with diabetes team | 974 (889 to 1059) | 720 (658 to 782) | 254 (147 to 361) | <0.001 |

| Other health professionals | 0 (−0. to 0) | 1 (−1 to 4) | −1 (−4 to 1) | 0.223 | |

| Tests and investigations | 55 (49 to 61) | 62 (56 to 67) | −7 (−15 to 1) | 0.100 | |

| Hospital stay | 0 | 2583 (2464 to 2702) | −2583 (−2702 to −2463) | <0.001 | |

| Nurse travel | 133 (107 to 159) | 18 (8 to 28) | 115 (86 to 143) | <0.001 | |

| Dietician travel | 3 (1 to 5) | 1 (−1 to 2) | 2 (0 to 5) | 0.039 | |

| Total cost days 0–3 | 1163 (1079 to 1248) | 3386 (3261 to 3511) | −2223 (−2373 to −2072) | <0.001 | |

| Follow-up (24 months) | Contact with the diabetes team | 1984 (1876 to 2092) | 2017 (1915 to 2119) | −33 (−182 to 116) | 0.664 |

|

1400 (1344 to 1455) | 1392 (1341 to 1443) | 8 (−67 to 83) | 0.837 | |

|

584 (502 to 667) | 625 (541 to 709) | −41 (−160 to 79) | 0.502 | |

| Hospital contacts | 897 (569 to 1225) | 860 (553 to 1167) | 37 (−413 to 487) | 0.874 | |

| Tests and investigations | 8 (5 to 11) | 8 (6 to 11) | −1 (−4 to 4) | 0.968 | |

| Total insulin | 457 (402 to 512) | 446 (397 to 495) | 11 (−63 to 85) | 0.773 | |

| Equipment | 1745 (1567 to 1924) | 1714 (1544 to 1883) | 31 (−218 to 281) | 0.803 | |

| Other health professional visits | 195 (149 to 240) | 236 (177 to 295) | −41 (−115 to 33) | 0.278 | |

| Total follow-up cost | 5287 (4864 to 5709) | 5282 (4883 to 5680) | 5 (−584 to 594) | 0.986 | |

| Total cost at 24 months | 6450 (6004 to 6897) | 8668 (8255 to 9080) | −2217 (−2825 to −1609) | <0.001 | |

| Patient/carer costs | |||||

| Days 0–3 | Days off school | 66 (56 to 75) | 57 (47 to 67) | 8 (−5 to 22) | 0.235 |

| Days off work | 250 (203 to 297) | 256 (201 to 310) | −5 (−77 to 66) | 0.886 | |

| Travel | 11 (9 to 12) | 18 (15 to 21) | −8 (−11 to −4) | <0.001 | |

| Out of pocket expenses | 8 (7 to 10) | 22 (17 to 27) | −14 (−19 to −8) | <0.001 | |

| Total cost days 0–3 | 331 (280 to 383) | 352 (292 to 412) | −21 (−101 to 59) | 0.601 | |

| Follow-up (24 months) | Days off school | 443 (363 to 523) | 454 (349 to 559) | −11 (−143 to 122) | 0.871 |

| Days off work | 869 (609 to 1128) | 1180 (679 to 1681) | −312 (−871 to 247) | 0.275 | |

| Travel | 63 (56 to 71) | 61 (49 to 72) | 3 (−11 to 17) | 0.687 | |

| Out of pocket expenses | 44 (32 to 56) | 42 (30 to 54) | 2 (−15 to 20) | 0.779 | |

| Total follow-up cost | 1420 (1134 to 1705) | 1737 (1207 to 2267) | −317 (−916 to 281) | 0.297 | |

| Total cost at 24 months | 1751 (1448 to 2054) | 2089 (1547 to 2631) | −338 (−963 to 286) | 0.290 | |

| Total cost | 8201 (7585 to 8817) | 10 757 (10 050 to 11463) | −2556 (−3494 to −1618) | <0.001 | |

Table 2.

Units of resource use

| Home management (n=98) | Hospital management (n=95) | ||||||

| Median | Range | Median | Range | ||||

| Minimum | Maximum | Minimum | Maximum | ||||

| Direct healthcare resource use | |||||||

| Days 0–3 | Contacts with the diabetes team | ||||||

|

1.0 | 0.0 | 9.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 | |

|

1.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 10.0 | |

|

|||||||

| Face to face | 6.0 | 0.0 | 13.0 | 6.0 | 0.0 | 32.0 | |

| Telephone calls/emails | 2.0 | 0.0 | 28.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.0 | |

|

1.0 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 3.0 | |

| Other healthcare professionals | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | |

| Test and investigations | |||||||

|

4.0 | 0.0 | 8.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 12.0 | |

|

2.0 | 0.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 6.0 | |

| Hospital stay (days) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 6.0 | |

| Travel | |||||||

|

40.0 | 0.0 | 214.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 192.0 | |

|

0.0 | 0.0 | 24.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 32.0 | |

| Follow-up (24 months) | Contacts with the diabetes team | ||||||

|

9.0 | 6.0 | 18.0 | 9.0 | 6.0 | 16.0 | |

|

28.5 | 2.0 | 128.0 | 31.0 | 2.0 | 158.0 | |

| Hospital contacts | |||||||

|

0.0 | 0.0 | 8.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.0 | |

|

0.0 | 0.0 | 16.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.0 | |

| Tests and investigations‡ | 0.0 | 0.0 | 11.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.0 | |

| Insulin | 18 889.5 | 2138.0 | 64 354.0 | 19 669.0 | 2351.5 | 48 858.0 | |

| Other health professionals | |||||||

|

2.0 | 0.0 | 14.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 19.0 | |

|

1.0 | 0.0 | 8.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 31.0 | |

|

0.0 | 0.0 | 11.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 22.0 | |

| Patient/carer resource use | |||||||

| Days 0–3 | Days off school | 2.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 |

| Days off work | 2.0 | 0.0 | 9.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 14.0 | |

| Travel (hours) | 2.0 | 0.0 | 7.0 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 16.0 | |

| Out of pocket expenses (£) | 11 | 0 | 38 | 16 | 0 | 87 | |

| Follow-up (24 months) | Days off school | 11.0 | 0.0 | 64.0 | 11.0 | 0.0 | 129.0 |

| Days off work | 3.3 | 0.0 | 70.0 | 4.0 | 0.0 | 164.0 | |

| Travel (hours) | 10.0 | 0.0 | 96.0 | 9.0 | 0.0 | 92.0 | |

| Out of pocket expenses (£) | 33 | 0 | 546 | 27 | 0.0 | 468 | |

| Total patient/carer resource use | Days off school | 13.0 | 0.0 | 66.0 | 13.5 | 0.0 | 132.0 |

| Days off work | 5.0 | 0.0 | 78.0 | 6.5 | 0.0 | 167.5 | |

| Travel (hours) | 12.0 | 3.0 | 99.0 | 13.0 | 0.0 | 94.0 | |

| Out of pocket expenses (£) | 43 | 0 | 546 | 48 | 0 | 555 | |

*Two patients had visits with the nurse outside of the patient setting.

†Home visits, telephone calls and emails.

‡From CRF 7 only.

CRF, case report form; GP, general practitioner.

Non-healthcare resource use and costs

There were no significant differences between home or hospital in either the number of days off school or work during the initiation period (0–3 days) (table 2); and this remained similar between groups over the 24-month follow-up period. Home management was not found to be significantly less costly than hospital management for patients and their carers at 0–3 days (−£21; 95% CI −£101 to £59; p=0.607) or 24 months (£338; 95% CI −£963 to £286; p=0.288) (table 1).

Healthcare and non-healthcare costs

Overall, home management was significantly less costly than hospital management for the base case analysis (−£2217; 95% CI −£2825 to −£1609, p<0.001). The difference in costs to the patient and their carers between home and hospital management was not statistically significant. However, adopting a wider perspective which encompasses direct NHS costs and patient/carer borne costs, led to home management being significantly less costly (−£2556; 95% CI −£3494 to −£1618; p<0.001) (table 3). Full costs, confidence intervals and significance levels for all resource use data collected are presented in online supplemental tables 8–13.

Table 3.

Cost-effectiveness results for each analysis scenario

| Analysis scenario | Incremental cost (£)*, 95% CI, p value | Incremental effect (HbA1c in mmol/mol), 95% CI, p value | ICER†, 95% CI, p value, quadrant | Cost-effectiveness probability for given WTP (%) | ||

| £5000 | £10 000 | £15 000 | ||||

| Direct healthcare perspective | −2182 to –2783 to −1581, <0.001 | −0 to –6 to 6, 0.923 | 7434, –73369 to 88237, 0.857 dominant | 51.2 | 48.8 | 48.1 |

| Direct healthcare + patient/carer perspective | −2520 to –3465 to −1576, <0.001 | −0 to –6 to 6, 0.923 | 8585, –91610 to 108781, 0.867 dominant | 51.9 | 49.6 | 48.3 |

| Sensitivity analysis | −1600 to –2198 to −1002, <0.001 | −0 to –6 to 6, 0.923 | 5451, –57926 to 68828, 0.866, dominant | 50.3 | 48.4 | 47.6 |

*Difference in cost between home and hospital management.

†(£ saved per additional unit change in HbA1c (mmol/mol)).

HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; WTP, willing to pay.

Cost-effectiveness

Home management dominated hospital management. In the base-case analysis, the ICER was £7434 saved per additional mmol/mol reduction of HbA1c (table 3). Based on the bootstrapped analysis for consideration of the joint uncertainly in costs and effects, the cost-effectiveness plane shows that home management has the potential to be cost saving for the NHS without changing clinical effectiveness (figure 1). The CEAC is somewhat counterintuitive for cost-saving interventions, in that the probability of home management being cost-effective reduces to 50% when the willingness to pay increases to £7770 per unit reduction of HbA1c (mmol/mol) (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Cost-effectiveness plane of base-case analysis. Reduction in HbA1c represents improvement. ●=point estimate ICER £7434 per mmol/mol reduction of HbA1c (−0.294, −£2182). HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin.

Figure 2.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve for base case analysis. Represents the probability of home management being cost-effective at different willingness-to-pay thresholds. HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin

An alternative unit cost for an overnight paediatric stay in hospital was explored through a univariate sensitivity analysis. This figure was based on a previous study,32 inflated to the current year, to give a value of £692. This had no significant impact on the ICER (£5451 saving per additional unit reduction in HbA1c (mmol/mol)) and the difference in direct healthcare costs between home and hospital at 24 months remained statistically significant (table 3, online supplemental figures 1 and 2).

bmjopen-2020-043523supp002.pdf (42.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043523supp003.pdf (52.9KB, pdf)

Adopting a broader cost perspective by incorporating both direct healthcare and non-healthcare costs, the ICER increased to £8585 saving per additional mmol/mol reduction of HbA1c (table 3). This does not have a significant effect on the distribution on the cost-effectiveness plane or on the probability of home management being cost-effective (online supplemental figures 3 and 4). Home management remained the dominant strategy.

bmjopen-2020-043523supp004.pdf (36.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043523supp005.pdf (50.5KB, pdf)

Cost–consequences analysis

A table presenting costs alongside psychological, physical and social consequences reported in the main trial is displayed in online supplemental table 14. Outcomes are taken from the child questionnaires.

Discussion

This economic evaluation was designed to assess whether delivering management at home for children with T1D who are clinically well at diagnosis would represent a cost-effective strategy for the NHS. The results indicate that the difference between home and hospital management in terms of direct NHS costs over 24 months, of £2182 per patient, favours home management. Uncertainty analysis indicated that the probability of home management being cost saving was 1.0. The greatest driver of differences in healthcare costs was the cost of hospitalisation during the initiation period. The ICER for the base-case analysis indicated that home management was dominant, with £7434 saved per additional unit reduction in mmol/mol of HbA1c. Sensitivity analysis indicated that the cost-effectiveness was stable to the choice of which costs were included. However, there is considerable uncertainty around the difference in effect (HbA1c), reflected in the probability of the cost-effectiveness on the CEAC being ~0.5 even at high thresholds of willingness to pay.

Strengths and weaknesses

The major strength of this evaluation is that it is based on an RCT, which reduces the risk for potential bias and uses patient-level data. The analysis was conducted in line with the main trial to ensure consistency and methods followed the NICE reference case.

A limitation of this study is that QALYs were not used as the measure of health outcome. The main trial did not collect data on health-utility in order to estimate QALYs due to the lack of a validated paediatric utility measure at the time of study commencement, especially in younger children.33 Therefore, we are unable to determine whether the ICER would be acceptable, given the NICE threshold of £20 000–30 000 per QALY. However, HbA1c is known to be a useful surrogate outcome measure in assessing the effectiveness of interventions for T1D as it is positively associated with an increased risk of long-term complications.34 35 The A Diabetes and Psychological Therapies (ADaPT) study of a diabetes-specific psychological intervention administered by diabetes nurses is an example of a trial which reports costs alongside HbA1c improvement, in addition to QALYs. The authors state that basing cost-effectiveness on HbA1c outcomes rather than QALYs can lead to higher probabilities of cost-effectiveness and this is an important point to be aware of when interpreting our results.36 However, their ICER of £457 per 1 mmol/mol decrease in HbA1c is based on spending more for decreases in HbA1c, not saving costs as in our ICER, and therefore is not comparable for interpreting WTP.

This leads to a second limitation in that we chose not to perform long-term extrapolation to assess the cost-effectiveness over a patient’s lifetime. Life-time extrapolation relies on economic models which use QALYs as the measure of effect. However, despite many models existing for use in T1D, a lack of validation in the paediatric setting undermines their application in the context of the DECIDE trial.37 Moreover, as there was no statistically significant difference in clinical effectiveness, this would also require assumptions on long-term benefits which could introduce bias.

The accuracy of the final unit costings may have been impacted by varying interpretation of CRFs and ability to recall, as parents were asked to recall answers by nurses who then completed the forms. However, questions about resource use were limited to a 3-month recall period, which is the general recall period for trial-based economic evaluations.38 Completion rates of forms were also high, with a small proportion of missing data. In addition, there are a number of methodological challenges in assigning costs to days of missed schooling, with no clear consensus on the most appropriate approach.39 We costed the time taken off school based on calculating an average cost spent per pupil per day, based on the Annual Report on Education Spending in England.24 This may underestimate the economic consequences of forgone leisure time and educational achievement.

A final limitation is that there have been changes in practice and consequently resource use and costs since the trial commenced. For example, test and investigation use was costed from one site only and this figure is likely to differ across centres. However, all costs were updated to, or based on, most recent figures to ensure relevance to the current NHS costs and any differences between sites to the overall outcomes was considered likely to be small and therefore unlikely to effect the overall findings. It should also be noted that at the time this study was conducted, few patients were using continuous glucose monitoring to allow us to collect data on ‘time in range’.

Context in the current literature

This is the first cost-effectiveness evaluation to compare home vs hospital management of T1D at diagnosis in children and young people in a UK setting. Costs were based on the UK healthcare system (NHS) and taken from national UK databases. The trial was conducted over eight different centres throughout the UK and hospital management was pragmatic, following local standard practice, which increases our confidence in the generalisability of the results to other areas of the UK.

The findings of this evaluation are comparable to other studies.5 13 However, interpretation of previous studies is limited by the use of small sample sizes, non-UK settings and all of them involved ‘hybrid’ models of care; meaning ‘home management’ involved care within the hospital and home/outpatient setting. Therefore, previous studies have not evaluated home care exclusively from the day of diagnosis and their reproducibility within the UK healthcare setting may be limited.

Implications for practice and research

Home management led to significant cost reductions for the NHS at both 3 days and 24 months. This economic evaluation, alongside the main trial provides evidence for home care being the first line approach for management of T1D at diagnosis in children who are clinically well. However, since the start of this trial, education has become more intensive and insulin delivery and blood glucose monitoring more complex. As a result, many centres choose to admit all patients by default, despite NICE guidance supporting home management.10 The identified cost saving of around £2000 per patient (over 2 years) could be invested in community services to manage this increased demand on healthcare professionals, increasing the feasibility of delivering a package of care which would normally be delivered in hospital.

It is envisaged that the results of this analysis will contribute to the evidence supporting future updates of NICE guidelines on management of T1D in children and adolescents at diagnosis. Further research could involve testing a hybrid model of care within the UK setting, incorporating updates in the management approach and measuring costs and utility.

Conclusion

Home management from diagnosis of T1D for children who are medically stable represents a saving of £2182 per patient with no significant impact on clinical effectiveness. These findings add to the main DECIDE trial which demonstrated that home management at the onset of T1D did not lead to any significant differences in glycaemic control. With incidence of T1D increasing and the demand for hospital beds rising, implementation of this approach as standard practice could prove to be a cost-saving step in the patient pathway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge with thanks the trial funders Diabetes UK and all the patients and carers participating in the trial. The Centre for Trials Research receives funding by the Welsh Government through Health and Care Research Wales and the authors gratefully acknowledge the Centre’s contribution to trial implementation. The authors acknowledge the contribution of Prof Kerry Hood who contributed to the initial trial design and conduct throughout; Mirella Longo and Prof David Cohen who contributed to the design of the health economic methodology, prior to, and during data collection. Trial Steering Committee (Adele McEvilly, Chris Patterson and Michael Bowdery), chaired by Dr Peter Swift; the trial administrator, Jackie Swain; the clinical teams at each of the 8 trial sites, the DECIDE project nurses and research nurses from NISCHR who provided support to the trial; the participating NHS Trusts and local Principal Investigators were The Royal Hospitals Belfast Health and Social Care Trust (Dr Dennis Carson), Cambridge (Dr Carlo Acerini), Cardiff and Vale NHS Trust (Prof JW Gregory and Dr JT Warner), Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust (Dr Verghese Mathew), Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust, Liverpool (Dr Princy Paul), Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals Foundation NHS Trust (Dr Tim Cheetham), Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust (Dr Tabitha Randell), University Hospital, Southampton NHS Trust (Dr Nicola Trevelyan and Dr Justin Davies); the stakeholders and others who have contributed.

Footnotes

Twitter: @HughesDyfrig

Contributors: ZM had full access to all the data in the study, conducted the analyses and drafted the manuscript. JT, JWG, TP and DAH supervised ZM and take responsibility of the study in its entirety and for the decision to submit for publication. JWG, RP and MR were responsible for developing the initial DECIDE research question and trial design, and implementation of the trial protocol. DAH, TP and RP were responsible for all statistical considerations and analysis. DAH was responsible for designing the health economics study. All those listed as authors contributed to the trial delivery and health economics study and were responsible for reading, commenting upon, and approving the final manuscript. The manuscript’s guarantors (JT, JWG and DAH) affirm that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Funding: This work was supported by Diabetes UK grant number RD06/0003353.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Deidentified participant data will be made available to the scientific community with as few restrictions as feasible, while retaining exclusive use until the publication of major outputs. Data will be available via the corresponding author.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Multicentre approval was granted by Research Ethics Committee for Wales (07/MRE09/59). Site-specific approval was granted by participating Acute Trust Research and Development Departments. The trial sponsor was Cardiff University.

References

- 1.Diabetes UK . The cost of diabetes report. Available: https://www.diabetes.org.uk/ [Accessed 17 Mar 2021].

- 2.NHS long term plan, 2019. Available: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/

- 3.NHS England . NHS five year forward view, 2014. Available: https://www.england.nhs.uk/five-year-forward-view/ [Accessed 17 Mar 2021].

- 4.Swift PG, Hearnshaw JR, Botha JL, et al. A decade of diabetes: keeping children out of hospital. BMJ 1993;307:96–8. 10.1136/bmj.307.6896.96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clar C, Waugh N, Thomas S, et al. Routine hospital admission versus out-patient or home care in children at diagnosis of type 1 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;31. 10.1002/14651858.CD004099.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lowes L, Lyne P, Gregory JW. Childhood diabetes: parents’ experience of home management and the first year following diagnosis. Diabet Med 2004;21:531–8. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01193.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health . National paediatric diabetes audit 2017 - 2018 (version 2), 2019. Available: https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/npda-annual-reports

- 8.Diabetes UK . Type 1 diabetes. Available: https://www.diabetes.org.uk/type-1-diabetes [Accessed 17 Mar 2021].

- 9.Gubitosi-Klug RA, DCCT/EDIC Research Group . The diabetes control and complications trial/epidemiology of diabetes interventions and complications study at 30 years: summary and future directions. Diabetes Care 2014;37:44–9. 10.2337/dc13-2148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.NICE . Diabetes (type 1 and type 2) in children and young people: diagnosis and management | Key-priorities-for-implementation. Guidance and guidelines, 2015. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng18/chapter/key-priorities-for-implementation#.V3uVbDnLUs8.mendeley [Accessed 17 Mar 2021].

- 11.Commodari E. Children staying in hospital: a research on psychological stress of caregivers. Ital J Pediatr 2010;36:40. 10.1186/1824-7288-36-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dougherty G, Schiffrin A, White D, et al. Home-Based management can achieve intensification cost-effectively in type I diabetes. Pediatrics 1999;103:122–8. 10.1542/peds.103.1.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tiberg I, Lindgren B, Carlsson A, et al. Cost-effectiveness and cost-utility analyses of hospital-based home care compared to hospital-based care for children diagnosed with type 1 diabetes; a randomised controlled trial; results after two years’ follow-up. BMC Pediatr 2016;16:1–12. 10.1186/s12887-016-0632-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gregory JW, Townson J, Channon S, et al. Effectiveness of home or hospital initiation of treatment at diagnosis for children with type 1 diabetes (DECIDE trial): a multicentre individually randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2019;9:e032317. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Townson JK, Gregory JW, Cohen D, et al. Delivering early care in diabetes evaluation (DECIDE): a protocol for a randomised controlled trial to assess hospital versus home management at diagnosis in childhood diabetes. BMC Pediatr 2011;11:7. 10.1186/1471-2431-11-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Guide to the methods of technology appraisal: NICE process and methods guides No. 9. London, 2013. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27905712/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.López-Bastida J, López-Siguero JP, Oliva-Moreno J, et al. Social economic costs of type 1 diabetes mellitus in pediatric patients in Spain: CHRYSTAL observational study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2017;127:59–69. 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.02.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curtis L, Burns A. Unit costs of health and social care 2019. Canterbury 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 19.NHS Improvement and NHS England . Annex A: the national tariff workbook, 2020. Available: https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/national-tariff/

- 20.CCEMG-EPPI . CCEMG - EPPI-centre cost converter v.1.4, 2019. Available: https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/costconversion/ [Accessed 17 Mar 2021].

- 21.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . BNF for children: British National formulary, 2020. Available: https://bnfc.nice.org.uk/ [Accessed 17 Mar 2021].

- 22.NHS Business Services Authority . NHS electronic drug tariff, 2020. Available: http://www.drugtariff.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/ [Accessed 17 Mar 2021].

- 23.Office for National Statistics . Employee earnings in the UK: office for national statistics 2019, 2020. Available: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/bulletins/annualsurveyofhoursandearnings/2020 [Accessed 17 Mar 2021].

- 24.Belfield C, Farquharson C, Sibieta L. Annual report on education spending in England. London, 2018. www.ifs.org.uk [Google Scholar]

- 25.Office for National Statistics . Consumer price inflation, UK, 2020. Available: https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices/bulletins/consumerpriceinflation/previousReleases [Accessed 17 Mar 2021].

- 26.IBM Corp . IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gomes M, Ng ES-W, Grieve R, et al. Developing appropriate methods for cost-effectiveness analysis of cluster randomized trials. Med Decis Making 2012;32:350–61. 10.1177/0272989X11418372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.StataCorp . Stata statistical software: release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Briggs AH, O’Brien BJ, Blackhouse G. Thinking outside the box: recent advances in the analysis and presentation of uncertainty in cost-effectiveness studies. Annu Rev Public Health 2002;23:377–401. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.23.100901.140534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fenwick E, O’Brien BJ, Briggs A. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves – facts, fallacies and frequently asked questions. Health Econ 2004;13:405–15. 10.1002/hec.903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) - explanation and elaboration: a report of the ISPOR health economic evaluation publication guidelines good reporting practices task force. Value Health 2013;16:231–50. 10.1016/j.jval.2013.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harron K, Mok Q, Dwan K, et al. CATheter Infections in CHildren (CATCH): a randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation comparing impregnated and standard central venous catheters in children. Health Technol Assess 2016;20:1–219. 10.3310/hta20180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen G, Ratcliffe J. A review of the development and application of generic multi-attribute utility instruments for paediatric populations. Pharmacoeconomics 2015;33:1013–28. 10.1007/s40273-015-0286-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nordwall M, Abrahamsson M, Dhir M. Impact of HbAlt1c\lt followed from onset of type 1 diabetes, on the development of severe retinopathy and nephropathy: the VISS study (vascular diabetic complications in Southeast Sweden). Diabetes Care 2015;38:308 LP–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Virk SA, Donaghue KC, Cho YH, et al. Association between HbA1c variability and risk of microvascular complications in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016;101:3257–63. 10.1210/jc.2015-3604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ismail K, Maissi E, Thomas S, et al. A randomised controlled trial of cognitive behaviour therapy and motivational interviewing for people with type 1 diabetes mellitus with persistent sub-optimal glycaemic control: a diabetes and psychological therapies (ADaPT) study. Health Technol Assess 2010;14:1–101. 10.3310/hta14220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Valentine WJ, Pollock RF, Saunders R, et al. The prime diabetes model: novel methods for estimating long-term clinical and cost outcomes in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Value Health 2017;20:985–91. 10.1016/j.jval.2016.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ridyard CH, Hughes DA. Methods for the collection of resource use data within clinical trials: a systematic review of studies funded by the UK health technology assessment program. Value Health 2010;13:867–72. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2010.00788.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andronis L, Maredza M, Petrou S. Measuring, valuing and including forgone childhood education and leisure time costs in economic evaluation: methods, challenges and the way forward. Soc Sci Med 2019;237:112475. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-043523supp001.pdf (221.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043523supp002.pdf (42.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043523supp003.pdf (52.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043523supp004.pdf (36.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-043523supp005.pdf (50.5KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Deidentified participant data will be made available to the scientific community with as few restrictions as feasible, while retaining exclusive use until the publication of major outputs. Data will be available via the corresponding author.