Abstract

Objective

To understand how a child with a stable chronic disease and his/her parents shape his/her daily life participation, we assessed: (1) the parents’ goals regarding the child’s daily life participation, (2) parental strategies regarding the child’s participation and () how children and their parents interrelate when their goals regarding participation are not aligned.

Methods

This was a qualitative study design using a general inductive approach. Families of children 8–19 years with a stable chronic disease (cystic fibrosis, autoimmune disease or postcancer treatment) were recruited from the PROactive study. Simultaneous in-depth interviews were conducted separately with the child and parent(s). Analyses included constant comparison, coding and categorisation.

Results

Thirty-one of the 57 invited families (54%) participated. We found that parents predominantly focus on securing their child’s well-being, using participation as a means to achieve well-being. Moreover, parents used different strategies to either support participation consistent with the child’s healthy peers or support participation with a focus on physical well-being. The degree of friction between parents and their child was based on the level of agreement on who takes the lead regarding the child’s participation.

Conclusions

Interestingly, parents described participation as primarily a means to achieve the child’s well-being, whereas children described participation as more of a goal in itself. Understanding the child’s and parent’s perspective can help children, parents and healthcare professionals start a dialogue on participation and establish mutual goals. This may help parents and children find ways to interrelate while allowing the child to develop his/her autonomy.

Keywords: cystic fibrosis, qualitative research, rheumatology

What is known about the subject?

An increasing number of children grow up with a chronic disease that majorly impacts their participation in daily life.

A child’s parents play an essential role in driving the child’s participation.

Understanding the parent’s as well as the child’s perspective helps lay the foundation for establishing mutual goals and a patient-centred approach regarding the child’s participation.

What this study adds?

Parents described participation as primarily a means to achieve the child’s well-being, whereas children described participation as more of a goal in itself.

The degree of friction between parents and their child was based on the level of agreement on who takes the lead regarding the child’s participation.

Starting a conversation regarding the child’s and parent’s goals and decisions may help children and parents find effective ways to interrelate.

Introduction

Children with a chronic disease are often unable to achieve the same level of participation in daily life as healthy children.1 WHO defines participation as ‘involvement in a life situation’, such as engaging in social interactions or taking on a role in sports or academia.2 A chronic disease can have a major impact on many aspects of life of both the child and his/her family.3–5 As an increasing number of children grow up with a chronic disease, the consequences of their disease on their daily life participation become increasingly evident.1 We previously described the child’s perspective on ‘full participation’ among children with a chronic disease.6 We found that these children feel that participation encompasses more than engaging in activities; indeed, they described having a sense of belonging, the ability to affect social interactions, and the capacity to keep up with healthy peers as key elements.6–10

Parents form their child’s primary social network and can have a major impact on their child’s daily life participation, especially because the presence of a chronic disease can affect the parent–child relationship and increases the child’s dependency.11–13 It is crucial to understand how parents perceive their child’s daily life participation, as well as their goals regarding their child’s participation.14 In addition to the child’s perspective, this can help lay the foundation for establishing mutual goals and a patient-centred approach regarding the child’s participation.12 15 16 Paired qualitative analyses in this field are scarce, but provide important insights into the child–parent relationship and the role of their collaboration in shaping the child’s daily life.17–19 The aim of this study was to determine: (1) the parent’s goal regarding the daily life participation of their child with a chronic disease, (2) parental strategies regarding the child’s participation and (3) how the child and his/her parents interrelate when their goals regarding the child’s participation are not aligned.

Methods

We used an explorative qualitative interview study design to examine parents’ view regarding their child’s participation, as well as how the child and his/her parents interrelate regarding the child’s participation. We used a general inductive approach and the Qualitative Analysis Guide of Leuven method proposed by Dierckx de Casterlé et al 20

Patient organisations were involved in setting the agenda and the priorities for this research. Children and their parents were involved in the conduct of this study. Patient organisations and societal partners are involved in the dissemination of our research.

Families were purposefully recruited in accordance with qualitative sampling strategies21 from the PROactive study cohort, which consists of children with cystic fibrosis, an autoimmune disease, or children within 1-year postcancer treatment at the Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital and the Princess Máxima Centre for Paediatric Oncology in the Netherlands. Children who were interviewed were 8–19 years of age, in a stable phase of their disease, and able to verbally communicate about their participation (both determined by their treating physician). Maximum variation was sought in the children’s age, sex, school absences and fatigue and pain levels.21 In the PROactive cohort, fatigue was assessed using the Multidimensional Fatigue Scale of the Paediatric Quality of Life Inventory,22 school absences over the previous 2 weeks and 6 months were reported, and average pain experienced over the previous week was reported on a Visual Analogue Scale.23

Families were approached by the child’s treating physician. If they were willing to participate, the child and his/her parent(s) were interviewed face to face at the same time (in separate interviews) by trained interviewers on qualitative interview techniques. The interviewers did not know the participants beforehand, and no characteristics or motivations of the interviewers were revealed before the interview. An in-depth semistructured interview lasting 60–90 min was used.24 The interviews were held by two female psychologists (EEBvdS and LNN; MSc) and one female medical doctor (MMN-vdV). We used separate interview guides covering the same topics for the children and parents, based on the published literature and the research team’s expertise. The interview began with an open-ended question. For parents this was: ‘What do you notice with respect to the impact that your child’s disease has on his/her participation in daily life?’. For children this was: ‘To what extent does your disease affect your daily life?’. We then focused on the children’s and parents’ experiences and perspectives. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim and field notes were made.

Data were analysed using two intertwined strategies, namely coding and theoretical thinking, while alternating between data collection and analysis.20 25 26 Our previous report focused on our analysis of the children’s interviews.6 Here, we first analysed all of the transcripts of the parents’ interviews and then analysed the children’s and parents’ paired transcripts in order to determine how children and their parents interrelate when their participation goals are not aligned. Two researchers (MMN-vdV and EEBvdS) started with open coding, after which the identified codes were reviewed by the remaining core team researchers (MCK and SLN) in order to reach consensus on the interpretation of the concepts. We used researcher triangulation and constant comparisons in order to achieve a thorough understanding of the qualitative material.20 25 The whole team, consisting of seven researchers from a variety of backgrounds, including paediatric nursing, medicine and psychology, checked the findings and validated the results. No repeat interviews were carried our nor were transcripts returned. Coding was achieved using the MAXQDA software program.27

Results

Of the 57 invited families, 31 (54%) participated. Reasons given for declining to participate included currently being involved in another study and the child finding it too burdensome to talk about his/her disease. We interviewed all 31 children (median age 13.1 (8.0–19.1); 61% girls) individually, as well as 22 mothers, 1 father and 8 parental couples (median parental age 48.1 (35.4–54.2); table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of the participating children and their parents

| Variable | Category | N | % | Median (IQR) |

| Parent(s) present at the interview | Mother | 22 | 71.0 | |

| Father | 1 | 3.2 | ||

| Both parents | 8 | 25.8 | ||

| Parent’s age (N=28)* | <40 years | 3 | 10.7 | 48.1 (35.4–54.2) |

| 40–49 years | 15 | 53.6 | ||

| ≥50 years | 10 | 35.7 | ||

| Child’s sex | Female | 19 | 61.3 | |

| Male | 12 | 38.7 | ||

| Child’s age | 8–11 years | 12 | 38.7 | 13.1 (8.0–19.1) |

| 12–15 years | 11 | 35.5 | ||

| 16–19 years | 8 | 25.8 | ||

| Disease/ condition |

Cystic fibrosis | 11 | 35.5 | |

| Autoimmune disease | 11 | 35.5 | ||

| Postcancer treatment | 9 | 29.0 | ||

| School presence in the past 2 weeks | Total | 31 | 100 | 100 (0–100) |

| ≥90% of the time | 21 | 77.8 | ||

| <90% of the time | 10 | 32.2 | ||

| Fatigue† | PedsQL general fatigue score (range 0–100) | 31 | 100 | 79.2 (25–100) |

| Fatigued (score of >1 SD below the reference values on PedsQL MFS) | 12 | 38.7 | ||

| Pain | VAS (range 0–10) | 31 | 100 | 2.0 (0–9) |

| VAS≥3 over the past week | 11 | 35.5 |

*Only available for 28 parents.

†Score 0–100, with lower scores indicating increased fatigue.

PedsQL MFS, Paediatric Quality of Life Inventory Multidimensional Fatigue Scale; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

Parental goals regarding the child’s participation

Parents reported they predominantly focus on securing their child’s current and future well-being. Well-being was defined as their child feeling good/happy or having a sense of fulfilment. Several domains can contribute to the child’s well-being; physical, social, spiritual and psychological well-being. Interestingly, we found that how parents react to their child with respect to his/her participation was not necessarily motivated by the disease specific factors; rather, they were motivated by their perception of their child’s well-being.

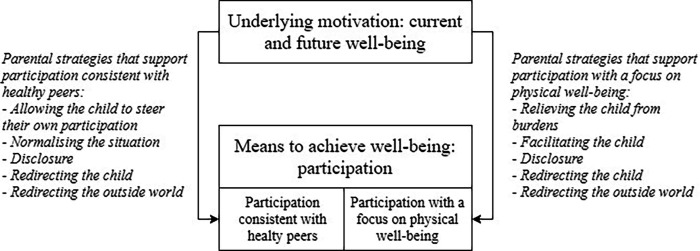

Participation was used as a means to accomplish well-being, but was not seen as a goal in itself. To increase their child’s participation, parents predominantly used two approaches: (1) participation that matches the level of their child’s healthy peers and (2) participation with a focus on physical well-being. Although parents sometimes switched between these approaches to secure well-being, many had a preference for one (box 1).

Box 1. Example illustrating a mother using the two participation approaches.

The mother of a 10-year-old boy with cystic fibrosis described: ‘It is difficult when he goes to a party or a disco that goes on a bit late. I want him to be able to join in, but for two days afterwards he is very bad-tempered and tired, and he complains of having a stomach ache.’ With the child’s well-being in mind, she can choose to let her son go to the party because she considers this beneficial to his current social, spiritual (sense of fulfilment) and psychological well-being, thereby meeting his desire to achieve full participation. Alternative, she can choose to not let her son go to the party because she believes the party would be dangerous to his physical well-being and that staying home will improve her son’s social and emotional well-being in the near future.

When parents used the first approach, their goal was for their child to be perceived by his/her peers as not different, even though he/she was unable to perform the same activities. Parents attempted to treat their child similarly to his/her siblings and friends. Parents chose this approach because it aligned with their child’s preferences, which supported his/her current well-being, or to help their child grow socially from a developmental perspective, which was expected to support his/her future well-being.

On the other hand, when parents used the second approach, they strive for their child to have as few symptoms as possible, investing in an optimal therapeutic regimen in order to control their child’s disease. Consequently, their child’s ability to participate at the same level as his/her healthy peers was replaced by other forms of participation they considered less threatening to the child’s physical well-being.

Parental strategies regarding the child’s participation

Figure 1 illustrates how the child’s well-being plays a role in how the child’s parents shape his/her participation, including the strategies parents can use to support the two approaches discussed above; these strategies are described in more detail in table 2. It is important to note that these various strategies require different amounts of parental investment, either personal, social or financial.

Figure 1.

How the child’s well-being, participation and parental strategies interrelate.

Table 2.

Parental strategies regarding their child’s participation identified in this study

| Parental strategy | Description | Example case |

| Allowing the child to steer their own participation | Using this strategy, parents attempted to let their child take the lead with as little interference as possible, in order to promote the child’s self-sufficiency and autonomy. | ‘I’m not the one who should forbid it. For example, she tried dancing for six months, and it didn’t go well at all. I could have forbidden it, but thought it was better that she found out for herself. Now she really likes free running, even though she can’t keep up. But the kids there know that, and she does what she can. She’s getting exercise, and she enjoys being part of a group. I can see she is benefitting from it and that it’s going well. But do I think it’s sensible? No, I don’t.’ |

| Normalising the situation | Using this strategy, parents promoted the belief that their child participates just like his/her healthy peers. They also either avoided or tried to change the perspective of others who view their child as limited compared with his/her peers. | ‘She now thinks her situation is normal; maybe she’s always in pain, but she doesn’t know any better. She just does everything. She says herself that this is her “normal” and that she doesn’t know any better than this. It has been like this since she was 5, and she doesn’t really know what normal is.’ |

| Relieving the child from burdens | Using this strategy, parents attempted to relieve their child from obligatory activities such as school, appointments, their therapeutic regimen or the child’s responsibility to disclose his/her limitations to others. | ‘So, we said it was OK to get a dog, but everyone will have to walk the dog every day, especially J, even in bad weather. But that’s not strictly true. I often do it in bad weather, because this time of year (fall), her symptoms are often worse.’ |

| Facilitating the child | Using this strategy, parents adjusted their own life and their family life as much as possible. The resources for achieving this strategy can be personal (eg, time investment such as a parent who quits his/her job in order to be home for the child), social (eg, siblings taking over the child’s tasks) or financial (eg, buying additional equipment). | ‘J. is going to high school next year, and we wonder how he’s going to get on. Right now, his bag is packed for him, including snacks; his exercise is arranged, and his bike is ready for him outside the door. His brother does all that for him now, but next year he’ll have to do it himself. Other 11-year-old boys can be allowed to bike to the gym on their own, but not J; we have to take him there and pick him up.’ |

| Disclosure | Using this strategy, parents directed the disclosure of their child’s disease and limitations to the outside world. In some cases, the parents deliberately chose not to disclose the child’s condition, or even temporarily withdrew the child from participating, in order to hide their child’s illness or limitations. Other parents chose to disclose the child’s disease and limitations on their child’s behalf so that the child did not have to do this him/herself and the environment could still be adjusted to accommodate the child’s capabilities. | Ex. 1) ‘She went into a new class, and we said that no one was allowed to ask M. anything about her condition. If they wanted to know anything, they were to come to us, and we would explain what happened and that she is now better. M. didn’t want to talk about it then, but now she’s opened up a bit.’

Ex. 2) ‘Because J. had a group of close friends, it wasn’t necessary to communicate it to the entire class. When he went to play with a friend, I just said that J. had a problem with his immune system and that there were some minor hygiene rules to follow, especially when he eats (he has to take pills before he eats anything). We keep it vague, so people don’t start Googling and labelling him; he can just be J.’ |

| Redirecting the child | Using this strategy, parents directly tried to influence the child and what he/she could do either by explicitly telling the child what he/she can and cannot do (eg, they cannot go on a school trip because it would make them too tired) or by attempting to persuade the child to do or not do certain activities (eg, to take their medication when away from home or to stop physical exercise when they experience pain). | ‘Yes, she didn’t need to make that decision. But that’s me; I make a lot of decisions on her behalf. I don’t know if this is a good thing or not, but both of us are very strict at home; we don’t believe much in that ‘yes, but’ culture. I am perfectly willing to explain why I made a certain decision, but we do what I decide we will do.’ |

| Redirecting the outside world | Using this strategy, parents tried to influence their child’s environment, for example, by asking the child’s teacher to give him/her a different seat in class so the child would be less cold, or persuading other parents to invite him/her to a party, even though their child may not be able to participate in all of the activities. | ‘When she started at a dance school, we spoke with them beforehand. But within two weeks she was sitting on the side for three-quarters of the hour. So we stopped taking her there. She’s now at another dance school; we spoke to the new dance teacher first, and she includes E. in everything. Her teacher even choreographs special dances for her, so she can take part in performances and demonstrations.’ |

How parents and their child interrelate

Most children indicated that their goal was to achieve full participation, while most parents indicated their goal was to optimise their child’s well-being, using participation as means, not as goal in itself. Sometimes, achieving both full participation and optimal well-being was possible based on the child’s and parent’s perception. However, especially among children whose well-being was decreased and among older children, the parents’ goals and the child’s goals sometimes drifted apart.

In these cases, we distinguish four ways in which parents and children interrelated to each other, based on who wants to take the lead regarding the child’s participation (Scenarios one to four in table 3). In scenarios one and four parents and child agreed on who took the lead, leading to minimal discussion and friction. In scenario two and three, parents and child did not agree on who took the lead, leading to more friction and sometimes decreased disclosure in the parent–child relationship (box 2). It is important to note that both the child and the parents can change their viewpoint over time and depending on the situation (box 3).

Table 3.

Four ways parents and their child interrelate when their goals are either aligned or not aligned, based on a combination of the parents’ viewpoint and the child’s viewpoint

| The parents’ viewpoint | |||

| We take the lead regarding the child’s participation | Our child takes the lead regarding his/her own participation | ||

| The child’s viewpoint | My parents take the lead regarding my participation | Scenario 1: The parents take the lead | Scenario 3: Neither the parents nor the child want to take the lead |

| I take the lead regarding my own participation | Scenario 2: Both the parents and the child want to take the lead | Scenario 4: The child takes the lead | |

Box 2. Example illustrating how children and parents may react when their participation goals are not aligned.

Some children stopped disclosing their limitations or symptoms to their parents, thereby reducing their parents’ ability to direct them. The mother of a 12-year-old girl which JIA describes: ‘She doesn’t want to be any different, and she wants to join in. So even if she’s in pain she won’t say so or give any indication that she’s in pain or can’t do something; she never says so.’ In response, the parents often attempted to ‘read’ how their child felt. One sixteen-year-old girl with JIA described: ‘They sometimes ask me if I’m still not feeling well. Every day I just say yes. Well, maybe not every day, you know what I mean; they ask about it sometimes, but I wouldn’t tell them myself.’

Box 3. Example illustrating a changing viewpoint of a parent regarding the child’s participation.

A mother of an 11-year-old girl with generalised morphea scleroderma describes: ‘We’ve had times when we had to be really confrontational, where we said to E., ‘You can’t do it, so you aren’t allowed to do it…’ Back then, she used to get really angry about things and cry. She understands better now. Last year one of her classmates was having a party at a trampoline centre, but E. said herself that she wasn’t going to go. She said, ‘I would really have to pay for it for three days afterwards; I wouldn’t be able to walk for three days.’ It’s still the same now; when we go there, she really goes crazy for a while. Well that’s fine, if she thinks she can do it. She knows she won’t be able to walk the next day, but she does it anyway. Fine, it’s her choice.’

We saw scenario one primarily in families in which the child was relatively young. This scenario did not lead to considerable friction, as the parent made the final decisions regarding the child’s participation, and the child followed their decisions. Scenario two was mostly seen in older children. As children grow older, they search to increase their level of autonomy and are able to guide their own participation. In some cases, however, the parents—particularly parents with a child who is more limited by his/her disease—found it difficult to allow their child to guide his/her own participation (boxes 2 and 4). This can lead to conflict between parent and child. Parents noted that they were continuously having to find a balance between their child’s growing autonomy and their own goals in securing the child’s well-being. In some cases (scenario 3), the parents wished their child was more autonomous, but the child did not want to take on the challenge of guiding his/her own participation. In the last scenario (scenario 4), the child becomes more autonomous, and the parents let him/her determine his/her own participation. The child essentially takes the lead, with the parents serving in a more advisory role. All scenarios are illustrated with examples in table 4.

Box 4. Example illustrating the way in which the child’s disease can interfere with his/her autonomy.

One mother of a 14-year-old boy with common variable immunodeficiency disorder described: ‘Because someone is ill, you start trying to fix things, which means you are actually not accepting someone for who they are. He can’t accept what he is, even though he wants nothing more than to be accepted for what he is. You very quickly notice that due to the disease the child’s ‘ownership’ of themselves is nipped in the bud, certainly when the child is so young. Ownership of the body, but also of decisions and thoughts; that’s what’s nipped in the bud, even though our society continually expects everyone to participate and be independent, and to own themselves. So, on one hand you take a lot away from the child, and on the other hand you force independence on them and expect them to undertake things. But when it comes to them wanting to make an autonomous decision about something like getting an injection, that’s different; whether they like it or not, they have to get it. It is horrible having to force a child to do awful things, both physically and mentally.’

Table 4.

Illustrative quotes for the four scenarios mentioned in table 3

| Way parents and child interrelate regarding the child’s participation | Example case |

| Scenario 1: Parents take the lead | The mother of an eight year-old girl with mixed connective tissue disease described: ‘Yes, she didn’t need to make that decision. But that’s me; I make a lot of decisions on her behalf. I don’t know if this is a good thing or not, but both of us are very strict at home; we don’t believe much in that ‘yes, but’ culture. I am perfectly willing to explain why I made a certain decision, but we do what I decide we will do.” The girl herself described it as follows: “I sometimes want to do things, but then mommy says that it’s probably better not to, because it will make me too tired.’ |

| Scenario 2: Both the parents and the child want to take the lead | The mother of a twelve-year-old girl with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) described: ‘She oversteps her boundaries. She is confrontational; she will become confrontational if she doesn’t want to do something or doesn’t want to admit something.” The girl herself described: “Most of the time my mother asks if I took my medication… Sometimes I just say ‘yes’ even if I didn’t take it; it’s annoying.’ |

| Scenario 3: Neither the parents nor their child want to take the lead | One mother of a 15-year-old boy with cystic fibrosis described her desire for her son to became more autonomous in terms of regulating his own therapeutic regimen and inviting friends over; however, when she saw that her son was not going to step up and take the lead and therefore jeopardized his well-being, she took back the lead: ‘I could tell him I wasn’t going to do it and back off. But then I know that it would all go wrong. I just think to myself, ‘Oh well, as long as he is at home and I am still able to do it for him.’ |

| Scenario 4: The child takes the lead | The mother of a 10-year-old girl with JIA: ‘I’m not the one who should forbid it. For example, she tried dancing for six months, and it didn’t go well at all. I could have forbidden it, but thought it was better that she found out for herself. Now she really likes free running, even though she can’t keep up. But the kids there know that, and she does what she can. She’s getting exercise, and she enjoys being part of a group. I can see she is benefitting from it and that it’s going well. But do I think it’s sensible? No, I don’t.’ Her daughter: ‘We often play ‘show-jumping’, where you put down blocks, lay a hockey stick across them, and then jump over the stick. Even though it isn’t very easy, I still join in and play it a lot.’ |

Discussion

We aimed to describe the parents’ and child’s perspective on the daily life participation among chronically ill children. We found that parents predominantly focus on securing their child’s well-being, using participation as a means to achieve well-being. We identified two approaches that parents take: (1) participation consistent with their child’s healthy peers and (2) participation with a focus on their child’s physical well-being. We found that parents use different strategies for supporting these approaches, and we found that friction can arise between parent and child when they felt different on who (ie, parents or child) should take the lead regarding the child’s participation.

A conceptual analysis based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health criteria describes participation as both a means and an end.28 Interestingly, in our interviews parents described participation as primarily a means to achieve well-being, whereas children described participation as more of a goal in itself, as we previously reported.6 This apparent discrepancy underscores the importance of establishing a dialogue regarding how participation should take place. Several aspects found in this study are in line with other major themes in qualitative studies among children with various chronic diseases and their parents. These include striving for normalcy or being more like the child’s healthy peers,29–34 and findings ways to manage the child’s disease and symptoms, although the way in which parents and children managed this sometimes differed.10 17 19 30 31 33 35–37

These differences in viewpoint between parents and children can give rise to friction. The presence of a chronic disease can influence both the parent–child relationship and the child’s path to autonomy, as it increases the child’s dependency, particularly when additional care is needed and given that parents wish to protect their child.12–14 34 In this regard, it is important to take the child’s age and developmental stage into account.38 In our study, we specifically saw that older children reported more friction and there was more often discussion regarding who should take the lead. Older children were also more capable to reflect on their own behaviour and that of their parents. Friction in the parent–child relationship has also been reported in other qualitative studies among young people with chronic diseases, which describe parents who find it difficult to allow their child to make his/her own choices, as well as children who feel unable to fulfil their desire for independence.10 15 17 33 Our finding that sometimes neither the parents nor the child want to take the lead is also consistent with several studies that found that young people can be hesitant to take the lead, as they feel safer with their parents.10 17 19 Therefore, opening a dialogue to discuss the parent’s and child’s perspective on the child’s participation may help children and parents better understand each other and may help them find ways to interrelate while giving the child more autonomy.

A major strength of this study is our paired analysis of qualitative material in which the child and his/her parent(s) were interviewed separately but simultaneously. This approach provides important insights into the parents’ and child’s views regarding participation and how these views interrelate among various paediatric chronic diseases.6 Finally, our analytical methods were designed to optimise both validity and reliability.21 26 Saturation was reached with respect to the goals for participation and how the child and his/her parents interrelate, although some aspects of the parental strategies may not have been fully revealed.

Limitations that warrant discussion include the limitations described in our previous report, such as the generalisability of our results, as we interviewed Caucasian families only. In addition, the parental interviews focused primarily on how their child viewed his/her participation and not necessarily how the parents defined the participation of the child, as our research design focused on the child.

With respect to the daily life participation of a chronically ill child, healthcare professionals should initiate a conversation regarding the parents’ and child’s goals, and the child’s autonomy as early as possible in order to observe and discuss changes over time.39 Helping children and parents to communicate with one another about how to adjust to life with a chronic disease, may be useful, for example using an online peer support group such as On Track.40 41 Also, interventions aimed at supporting children to grow towards autonomy may be of interest, such as Skills for growing up.42 For future studies, interventions that teach healthcare professionals how to start a dialogue with children and parents regarding their goals and preferences may be beneficial.39

Conclusions

To optimise the child’s daily life participation and well-being, understanding the parents’ goals and how parents and children interrelate can allow children, parents and healthcare professionals to start a dialogue on mutual goals. It may help children and parents find effective ways to interrelate, while allowing the child to increase his/her autonomy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of the patients and parents who participated in this study and the involved caregivers. The authors also thank dr. C.F. Barrett for his assistance with English language editing.

Footnotes

Contributors: LNN designed the study together with MCK, NN and MMN-vdV. MMN-vdV, EEBvdS, LNN collected the data. Initial coding and theoretical thinking was performed by a core team of four researchers (MMN-vdV, EEBvdS, LNN and MCK). Three researchers (LNN, EMvdP, MvG) checked the findings and validated the results. MvG, JFS, AvR-K and KvdE critically reviewed the data analyses and reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: No, there are no competing interests.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Authors can be contacted for data requests. Data are available on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The Institutional Review Board determined that this study was exempt from the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (16-797/C).

References

- 1. Perrin JM, Bloom SR, Gortmaker SL. The increase of childhood chronic conditions in the United States. JAMA 2007;297:2755. 10.1001/jama.297.24.2755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO . Global recommendations on physical activity for health; 2015. [PubMed]

- 3. Zan H, Scharff RL. The heterogeneity in financial and time burden of caregiving to children with chronic conditions. Matern Child Health J 2015;19:615–25. 10.1007/s10995-014-1547-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pinquart M, Teubert D. Academic, physical, and social functioning of children and adolescents with chronic physical illness: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Psychol 2012;37:376–89. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsr106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Leeman J, Crandell JL, Lee A, et al. Family functioning and the well-being of children with chronic conditions: a meta-analysis. Res Nurs Health 2016;39:229–43. 10.1002/nur.21725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nap-van der Vlist MM, Kars MC, Berkelbach van der Sprenkel EE, et al. Daily life participation in childhood chronic disease: a qualitative study. Arch Dis Child 2020;105:463–9. 10.1136/archdischild-2019-318062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Martin Ginis KA, Evans MB, Mortenson WB, et al. Broadening the conceptualization of participation of persons with physical disabilities: a configurative review and recommendations. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2017;98:395–402. 10.1016/j.apmr.2016.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Westergren T, Berntsen S, Ludvigsen MS, et al. Relationship between physical activity level and psychosocial and socioeconomic factors and issues in children and adolescents with asthma: a scoping review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep 2017;15:2182–222. 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Willis C, Girdler S, Thompson M, et al. Elements contributing to meaningful participation for children and youth with disabilities: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil 2017;39:1771–84. 10.1080/09638288.2016.1207716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hoefnagels JW, Kars MC, Fischer K, et al. The perspectives of adolescents and young adults on adherence to prophylaxis in hemophilia: a qualitative study. Patient Prefer Adherence 2020;14:163–71. 10.2147/PPA.S232393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Minuchin P. Families and individual development: provocations from the field of family therapy. Child Dev 1985;56:289–302. 10.2307/1129720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schmidt S, Petersen C, Bullinger M. Coping with chronic disease from the perspective of children and adolescents--a conceptual framework and its implications for participation. Child Care Health Dev 2003;29:63–75. 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2003.00309.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kars MC, Grypdonck MHF, de Bock LC, et al. The parents’ ability to attend to the “voice of their child” with incurable cancer during the palliative phase. Health Psychology 2015;34:446–52. 10.1037/hea0000166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wallander JL, Varni JW. Effects of pediatric chronic physical disorders on child and family adjustment. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1998;39:29–46. 10.1017/S0021963097001741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gutman T, Hanson CS, Bernays S, et al. Child and parental perspectives on communication and decision making in pediatric CKD: a focus group study. Am J Kidney Dis 2018;72:547-559. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Coyne I, Amory A, Kiernan G, et al. Children's participation in shared decision-making: children, adolescents, parents and healthcare professionals' perspectives and experiences. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2014;18:273–80. 10.1016/j.ejon.2014.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peeters MAC, Hilberink SR, van Staa A. The road to independence: lived experiences of youth with chronic conditions and their parents compared. J Pediatr Rehabil Med 2014;7:33–42. 10.3233/PRM-140272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fereday J, MacDougall C, Spizzo M, et al. "There's nothing I can't do--I just put my mind to anything and I can do it": a qualitative analysis of how children with chronic disease and their parents account for and manage physical activity. BMC Pediatr 2009;9:1. 10.1186/1471-2431-9-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hilberink SR, van Ool M, van der Stege HA, et al. Skills for growing Up-Epilepsy: an exploratory mixed methods study into a communication tool to promote autonomy and empowerment of youth with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2018;86:116–23. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.05.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dierckx de Casterlé B, Gastmans C, Bryon E, et al. QUAGOL: a guide for qualitative data analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 2012;49:360–71. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Creswell J. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. 3rd Ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gordijn MS, Suzanne Gordijn M, Cremers EMP, et al. Fatigue in children: reliability and validity of the Dutch PedsQL™ multidimensional fatigue scale. Qual Life Res 2011;20:1103–8. 10.1007/s11136-010-9836-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rosier EM, Iadarola MJ, Coghill RC. Reproducibility of pain measurement and pain perception. Pain 2002;98:205–16 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12098633 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00048-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded theory. 2nd Edition. USA: Sonoma State University, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ 2000;320:114–6. 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Morse JM, Barrett M, Mayan M, et al. Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods 2002;1:13–22. 10.1177/160940690200100202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. VERBI Software . MAXQDA 2018; 2018.

- 28. Imms C, Granlund M, Wilson PH, et al. Participation, both a means and an end: a conceptual analysis of processes and outcomes in childhood disability. Dev Med Child Neurol 2017;59:16–25. 10.1111/dmcn.13237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Harden J, Black R, Chin RFM. Families' experiences of living with pediatric epilepsy: a qualitative systematic review. Epilepsy Behav 2016;60:225-237. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.04.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bailey PK, Hamilton AJ, Clissold RL, et al. Young adults' perspectives on living with kidney failure: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019926. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tong A, Jones J, Craig JC, et al. Children’s experiences of living with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Arthritis Care Res 2012;64:1392–404. 10.1002/acr.21695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lambert V, Keogh D. Striving to live a normal life: a review of children and young people's experience of feeling different when living with a long term condition. J Pediatr Nurs 2015;30:63–77. 10.1016/j.pedn.2014.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jamieson N, Fitzgerald D, Singh-Grewal D, et al. Children's experiences of cystic fibrosis: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Pediatrics 2014;133:e1683–97. 10.1542/peds.2014-0009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Loades ME, James V, Baker L, et al. Parental experiences of adolescent cancer-related fatigue: a qualitative study. J Pediatr Psychol 2020;45:1093–102. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Belpame N, Kars MC, Beeckman D, et al. "The AYA Director": A Synthesizing Concept to Understand Psychosocial Experiences of Adolescents and Young Adults With Cancer. Cancer Nurs 2016;39:292–302. 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Quirk H, Blake H, Dee B, et al. "You can't just jump on a bike and go": a qualitative study exploring parents' perceptions of physical activity in children with type 1 diabetes. BMC Pediatr 2014;14:313. 10.1186/s12887-014-0313-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Smith J, Cheater F, Bekker H. Parents' experiences of living with a child with a long-term condition: a rapid structured review of the literature. Health Expect 2015;18:452–74. 10.1111/hex.12040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Heath G, Farre A, Shaw K. Parenting a child with chronic illness as they transition into adulthood: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of parents' experiences. Patient Educ Couns 2017;100:76–92. 10.1016/j.pec.2016.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fahner JC, Beunders AJM, van der Heide A, et al. Interventions guiding advance care planning conversations: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2019;20:227–48. 10.1016/j.jamda.2018.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Douma M, Maurice-Stam H, Gorter B, et al. Online psychosocial group intervention for parents: positive effects on anxiety and depression. J Pediatr Psychol 2021;46:123–34. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Scholten L, Willemen AM, Grootenhuis MA, et al. A cognitive behavioral based group intervention for children with a chronic illness and their parents: a multicentre randomized controlled trial. BMC Pediatr 2011;11:65. 10.1186/1471-2431-11-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sattoe JNT, Hilberink SR, Peeters MAC, et al. 'Skills for growing up': supporting autonomy in young people with kidney disease. J Ren Care 2014;40:131–9. 10.1002/jorc.12046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Authors can be contacted for data requests. Data are available on reasonable request.