Abstract

Introduction

Mainstream Australian mental health services are failing Aboriginal young people. Despite investing resources, improvements in well-being have not materialised. Culturally and age appropriate ways of working are needed to improve service access and responsiveness. This Aboriginal-led study brings Aboriginal Elders, young people and youth mental health service staff together to build relationships to co-design service models and evaluation tools. Currently, three Western Australian youth mental health services in the Perth metropolitan area and two regional services are working with local Elders and young people to improve their capacity for culturally and age appropriate services. Further Western Australian sites will be engaged as part of research translation.

Methods and analysis

Relationships ground the study, which utilises Indigenous methodologies and participatory action research. This involves Elders, young people and service staff as co-researchers and the application of a decolonising, strengths-based framework to create the conditions for engagement. It foregrounds experiential learning and Aboriginal ways of working to establish relationships and deepen non-Aboriginal co-researchers’ knowledge and understanding of local, place-based cultural practices. Once relationships are developed, co-design workshops occur at each site directed by local Elders and young people. Co-designed evaluation tools will assess any changes to community perceptions of youth mental health services and the enablers and barriers to service engagement.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has approval from the Kimberley Aboriginal Health Planning Forum Kimberley Research Subcommittee, the Western Australian Aboriginal Health Ethics Committee, and the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee. Transferability of the outcomes across the youth mental health sector will be directed by the co-researchers and is supported through Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal organisations including youth mental health services, peak mental health bodies and consumer groups. Community reports and events, peer-reviewed journal articles, conference presentations and social and mainstream media will aid dissemination.

Keywords: change management, health & safety, quality in health care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The project approach draws on the strength, wisdom and knowledge of Aboriginal Elders and young people within local areas.

Indigenous methodologies and participatory action research enhances respect for local Aboriginal traditions, customs and cultural worldviews at each site including varying experiences of colonisation.

Co-designing with youth mental health services has the potential for comparability and national generalisability, however, there is also potential tension between standardised models of care and ensuring that local community needs and cultural practices guide model development.

Partnerships with peak bodies and service providers facilitates rapid policy change.

The project benefits from Aboriginal leadership to facilitate two-way knowledge exchange.

Introduction

Colonial policies resulting in the systematic loss of land, language, culture, family connection and spiritual identity have had cumulative and intergenerational effects for Aboriginal peoples in Australia.1–3 Young people can be particularly vulnerable to the ongoing impact of colonisation, evidenced by the continued removal of children from their families into the care of non-Aboriginal people.4 Aboriginal young people in Australia face heightened risk for poor mental health,5 with Aboriginal children and adolescents aged 5–17 years dying from suicide at five times the rate of non-Aboriginal young people.6

Mental health systems, policies and practices continue to reinforce colonial ideologies in service provision.7 A lack of leadership and truth telling about the shared history of Australia has resulted in Aboriginal people having a deep mistrust of institutions including mainstream mental health services.8 Self-determination is critical to mental health services for Aboriginal people but is lacking from policy and practice.9 Culturally secure health service must therefore recognise Aboriginal cultural practices and worldviews, and work toward establishing relationships that engender a sense of trust between services, staff and Aboriginal people, their families and communities.10 11

Building the cultural capability of non-Aboriginal health professionals to increase the accessibility, responsiveness and cultural security12 of mainstream services is essential to improve outcomes for Aboriginal people.13 However, terminology surrounding the cultural capability of non-Aboriginal health professionals is contestable as there is a tendency to rely on cultural awareness training. Although an important step, the impact of awareness training is limited as it does little to change organisational culture or practice.14 It is widely acknowledged that cultural capability development is a continuum that occurs over time through ongoing contact to foster and build meaningful relationships that lead to greater understanding and respect for culture.10 14

Government policy emphasises co-designed responses to health inequities characterised by equal partnerships.15 16 However, what is lacking are directions on how to engage in culturally secure co-design processes that address colonialism, power inequalities, racism, white privilege and unconscious bias.10 17 Meaningfully engaging in a decolonising process requires co-design with Aboriginal people to reframe current responses to health inequities and to improve the accessibility and responsiveness of mainstream youth mental health services.10 18

This research addresses the lack of cultural security (which affects the accessibility and responsiveness of youth mental health services) and culturally appropriate evaluation tools to determine the effectiveness of services in meeting the needs of Aboriginal young people. The intended outputs and outcomes will occur through a culturally grounded, relationship-based process that will create and sustain partnerships with Aboriginal Elders, young people and youth mental health service staff. Participants will work together to co-design appropriate service models, system change interventions and evaluation tools to measure organisational change. Unique to this project is the drawing together of cultural protocols and research to develop innovative, decolonised service provision to improve the social and emotional well-being of Aboriginal youth. (the term ‘Aboriginal’ has been used in this article to refer to both the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of Australia. Our intention in using ‘Aboriginal’ is to acknowledge the significance of place and that this project will be conducted on Aboriginal country in Western Australia with different clan groups. The authors acknowledge that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples may identify with their local clan or group name and mean no disrespect in using the term Aboriginal).

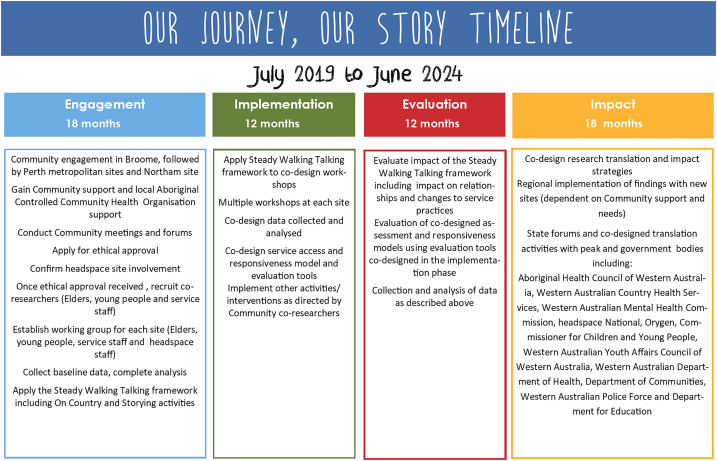

Steady Walking Talking co-design framework

The Steady Walking Talking co-design framework (figure 1) acknowledges and privileges Aboriginal ways of being, knowing and doing and underpins the participatory action research and co-design study methods.19 It, therefore, constitutes the methodological approach and informs the research methods that embody an Aboriginal worldview through the application of seven culturally informed conditions for the development of relationships. The seven conditions outlined in the co-design framework (see figure 1) are supported through immersive experiential learning sessions led and held by Elders as the cultural knowledge holders (described in more detail under the Methods section). The framework models the interconnected relationship between Aboriginal protocols, values, beliefs and research practices within Indigenous methodologies.20 The framework is decolonising and strengths-based and has proven to build the capability and confidence of non-Aboriginal people to change health service organisational culture. It was developed, tested and validated over 7 years of participatory action research with Nyoongar Elders in metropolitan Perth.19

Figure 1.

Steady Walking Talking co-design framework.

The framework was co-designed as one of three foundational components of a larger decolonising systemic change framework,19 and subsequently applied to improve the delivery of Aboriginal youth mental health services.21 Findings from prior research have shown that this type of engagement will build relationships, trust and mutual understanding.21 The process for building relationships takes time and is circular rather than didactic and linear. Importantly, non-Aboriginal service staff need to commit to being fully present and open to learning with humility.10

Methods and analysis

Study aims

This research aims to enhance the capacity of mainstream youth mental health service providers to be flexible, confident and competent when responding to the needs of Aboriginal young people. Specifically, the project will provide an evidence base that describes optimal youth mental health service accessibility and responsiveness to improve the social, emotional and mental well-being of Aboriginal young people. To achieve this, the Steady Walking and Talking co-design framework will be implemented across metropolitan Perth and regional Western Australia locations with different language and clan groups (the specific groups and settings are described in more detail under ‘Patient and public involvement’ and ‘Participants and setting’).

The research harnesses the cultural leadership of Aboriginal Elders and young people to alter the way services work with and for Aboriginal youth, their families and communities by:

Applying the co-design framework at each site in Western Australia so that local Elders, young people and youth mental health service staff can build and sustain relationships.

Co-designing governance structures, culturally secure clinical practices, community engagement and workforce strategies with local Aboriginal Elders, young people and service staff.

Evaluating the impact of the changes to systems and work practices on community perceptions, and the accessibility and responsiveness of youth mental health services and their effectiveness in meeting the needs of Aboriginal young people from different clan groups.

Ensuring the cultural and age appropriate services and systems changes have occurred. The evaluation measures will also be locally co-designed with Elders and young people.

Accordingly, the research aims to answer the following questions:

How do the seven conditions stated in the Steady Walking and Talking co-design framework establish relationships and trust between services and the Aboriginal community so they can work together in different regions?

How do the key attributes of a culturally secure health service meet the needs of young Aboriginal people who differ across Aboriginal clan groups?

How do the key criteria of a culturally secure youth mental health service evaluation differ across Aboriginal clan groups?

Has the framework resulted in more young Aboriginal people accessing these mental health services and with greater levels of satisfaction with the partner services?

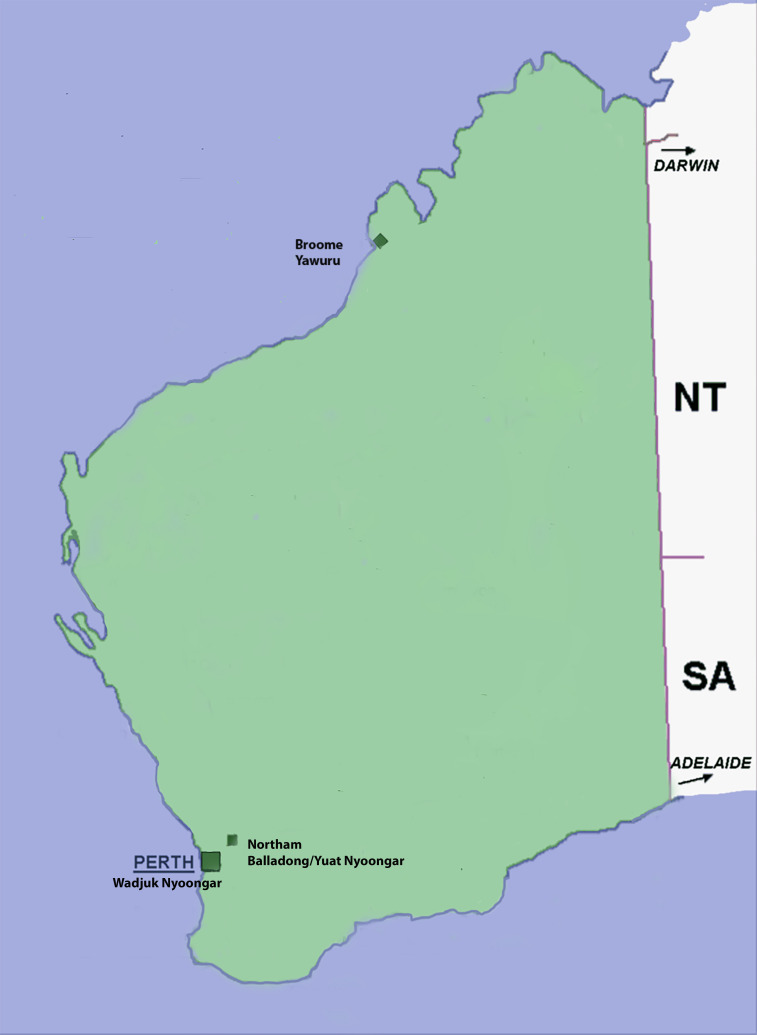

Study design

Participatory action research grounded in Indigenous research methodologies22–24 allows services and clinical models to evolve during the project. Aboriginal research and evaluation must respect Aboriginal worldviews, and be responsive to the self-determined intentions, priorities and drivers expressed by Aboriginal people.24 As Tuhiwai Smith has argued, Indigenous research methodologies involve ‘talking up to’ Western research practices that are ‘embedded in a global system of imperialism and power’ (Tuhiwai-Smith,20 pxi). In this study, therefore, the application of Indigenous research methodologies involves legitimising holistic Indigenous knowledge systems, reciprocity and relationship between researcher and participants as a natural part of research, collectivity and obligation as a way of knowing and valorising Indigenous methods such as storytelling.25 Participatory action research has been adopted as it aligns with collective consultative cultural practices and emphasises mutual respect and co-learning; individual and community building; systems change and a balance between research and action.24 26 Through participatory action research, Elders, young people and service staff engage as co-researchers, which is characterised by cyclical, narrative, dynamic and reflective processes. Additionally, the iterative nature of the research design and implementation promotes success.26 Figure 2 provides a timeline for the project activities.

Figure 2.

Project timeline.

Patient and public involvement

To decolonise youth mainstream mental health services and strengthen the well-being of Aboriginal young people, decolonising processes are essential to challenge the taken-for-granted assumptions, practices, hierarchies and language of Western knowledge systems including those evident in youth mental health services.27 To that end—and to honour Aboriginal collective consultation and decision-making processes—‘patient and public involvement’ in this project is better understood as ‘meaningful community involvement’ which encompasses Elders, young people (and through their connection to the broader community) others with lived experience of youth mental health services. ‘Meaningful community involvement’ is designed to ‘push back’ on transactional Western ways of being, doing and knowing by emphasising Aboriginal collective ways of working characterised by obligation and reciprocity.

‘Community’ has thus led and directed the formative research and leads and directs this project. First, the Steady Walking Talking framework, which holds and informs the research process, was co-designed by Nyoongar Elders. Second, Nyoongar Elders instructed the Our Journey, Our Story project’s focus on mainstream youth mental health services by highlighting the need for youth mental health services to improve their accessibility and responsiveness.21 Third, Aboriginal researchers are accountable to their communities, and are bound by cultural protocols and a constant feedback loop that ensures accountability. Fourth, participatory action research and co-design methods amplify and legitimise community voices and provide community members opportunities to further develop capacity to lead change for the benefit of their communities.24

The research team believes the community-led process of relationship building creates conditions that empower communities to influence strategic action for impact.8 Trusting and meaningful relationships are crucial as they enable non-Aboriginal service staff co-researchers to deepen their understanding of culture and spirit to inform changes to service delivery. The research questions for the project therefore reflect an Aboriginal worldview and are primarily concerned with processes that support relationship building. In the absence of trust, relationships that are formed, developed and maintained create positive local, place-based change that meets the collective priorities and needs of the communities involved.

The research team acknowledges the Nyoongar and Yawuru peoples as the custodians of the lands on which they are working. We wish to acknowledge those Aboriginal communities who guide and support the research and give consent to work on their country. Our heartfelt appreciation go to the Aboriginal Elders, young people and youth mental health service staff involved as co-researchers.

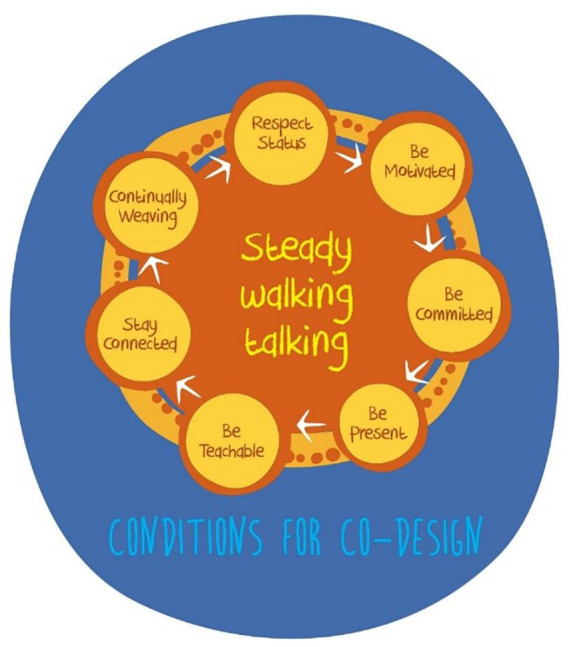

Setting and participants

The 5-year project runs from June 2019 to May 2024 and will be undertaken across metropolitan Perth and regional Western Australia in partnership with local headspace centres (henceforth referred to as sites). headspace is a federal government-funded youth mental health service that operates nationally with more than 110 centres offering tailored psychological intervention. The Steady Walking Talking co-design framework is currently being applied across three Perth metropolitan sites on Nyoongar Wadjuk country, one satellite site in rural Northam on Nyoongar Yuat/Balladong country and one on Yawuru country in Broome in the Kimberley region of Western Australia (see figure 3). Other Western Australian sites are planned as part of the research translation and their involvement will be determined by each community.

Figure 3.

Map of Western Australia with current sites.

Three groups of participants are being recruited for each site:

Elders, young people and headspace staff. These participants will be co-researchers and involved in co-design workshops. Approximately 3–5 local Elders (note that male and female representation for all participant groups will reflect local cultural protocols/context and will be determined through consultation with local communities through the co-researchers) (traditional owners where each of the sites are located) and 3–5 young people (ages 18–25 years) will be invited to participate. Exclusion criteria include anyone under 18 years and individuals acutely unwell with mental health difficulties, or persons with dependent relationships (such as those currently receiving treatment from the sites). It is vital that headspace co-researchers come from all levels of the organisation including executives, clinical, allied and administrative staff (approximately 3–5 from each partner service site). Although confidentiality will be maintained, co-researchers, due to their high-profile role in the co-design process, will be identifiable to other co-researchers and community members. Comprehensive culturally relevant information sheets in plain language are provided to ensure informed consent for all aspects of involvement in the research.

Clients at headspaces centres. Quantitative data will be collected from each of the sites. These data will be routinely collected and de-identified to maintain confidentiality. For example, data will include the number of Aboriginal young people triaged by each service; the number accepted by the service or referred elsewhere; and the median length of engagement with the service. Of note, due to the participatory action research methodology, the co-design process may point to other measures of service evaluation for which an ethics amendment will be sought.

Local Aboriginal community members. Community perceptions of headspace centres will be collected from an additional group of Aboriginal community members who provide informed consent. Approximately 20 people per site will be invited to participate in in-depth community interviews which will be audio recorded and transcribed.

Methods and planned analyses

Research activities conducted at each site will adopt participatory action research principles to ensure the research is community-led. Recruitment and engagement at each site will be informed by local cultural practices, context, needs and draw on existing relationships between investigators, the research team and community members. Of note, 7 of the 10 investigators are respected Aboriginal researchers with cultural connections across Western Australia and the project research team is also predominately Aboriginal. The project works to the rhythms of each community; this means a ‘steady, steady’ approach which respects and accepts the likely unavailability of the Aboriginal co-researchers due to cultural obligations. All Aboriginal community co-researchers receive proper compensation for their time in respect of their lived experience and expertise.

Engagement

In addition to the research team’s networks, co-researchers may be recruited through local forums. Relevant staff from each participating site will be recruited internally and each site’s youth reference group will also be engaged with to ensure ongoing youth participation. The relevance of the Steady Walking Talking co-design framework to different clan groups will be determined through each local communities’ engagement in the research. For example, Yawuru Elders and young people currently working with the research team at the Broome site have responded positively to the research team’s way of working—and the Steady Walking Talking co-design framework—as indicated by their regular attendance at project video conferences and engagement in research activities. Despite the framework being co-designed with Nyoongar Elders, the acceptance and positivity shown by Yawuru people suggests the seven steps to support relationship building in the framework is relevant to other clan groups.

Preparation for working together and co-design workshops

A series of workshops will be hosted in each site. As part of the preparation for co-design, Elders, young people and service staff will meet regularly for cultural teaching and mentoring including Storying and On Country experiential learning. As the name suggests, Storying provides a safe non-judgemental space for Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people to share their stories and histories and is a conduit for appreciating the impact of colonisation on health, well-being and identity.20 Findings have shown that Storying can deepen and sustain relationships over the course of a project.8 Storying provides the foundation for the On Country experience with Elders and provides the next steps for deepening relationships. This occurs through the experience of hearing and being shown how culture is experienced through the stories of being On Country.8 21 After establishing a strong foundation for working together, participants are ready for the co-design which will focus on changing work practices to increase Aboriginal youth engagement in mental health services and inform the development of outcome indicators. Comparison of co-designed service change priorities and evaluation indicators at each site with different clan groups will address Research Aims 2 and 3.

The co-design workshops will change and assess work practices to improve service access and responsiveness for young people. Workshop discussions will be audio-recorded and transcribed and supplemented by observation notes. The creation of a meaningful working together space, where Aboriginal people, Elders and young people are heard and can share their wisdom will deepen non-Aboriginal participants’ understanding of Aboriginal ways of working. Elders and young peoples’ relationships with service staff at all levels and continued engagement with the services—through an effective working together relationship—will similarly indicate whether there is trust in the service (Research Aim 1). Interviews, focus groups, and data gathered from co-design processes will be analysed to determine the level of commitment of all co-design participants to the process of relationship building and subsequent service changes. Evidence of meaningful changes to service practice, governance structures, inclusion of Elders and young people in decision-making, workforce, training and recruitment processes will be an indication of trust (Research Aim 1).

Staff turnover is a potential challenge to sustaining relationships. However, the period of relationship building and co-design workshops that occurs at each site over approximate two and a half years is ample time to manage staff transitioning in and out of the service. Similarly, the intention is to embed increased knowledge of Aboriginal ways of working into the organisation to sustain relationships and support service change. Young co-researchers also have the potential to move on, however, the process of working together—including the role of the Elders and research team in holding the young people—creates a safe environment for young people new to the project to build relationships.

Qualitative data analysis will employ an inductive approach, consistent with the principles of thematic content analysis.28 Two researchers (Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal) will code the data, and cross-code 10% of the dataset to establish inter-rater reliability.29 The initial themes will be presented to the co-researchers (Elders, young people and service staff co-researchers) for member checking before comprehensive coding and thematic analysis.

Clients at headspace centre sites

Service data will be analysed to track changes to service accessibility and responsiveness. Demographic and service use data for Aboriginal clients will be analysed to examine: accessibility (ie, how many are attending services), demographics (ie, who is attending services), acceptability (ie, length of time engaged), responsiveness (ie, type of services provided), severity at intake (ie, how unwell are youth at presentation) and satisfaction (ie, satisfaction with the services). Data will be analysed at baseline and annually to assess whether the co-design process results in improvements to accessibility, acceptability, intake severity and satisfaction. Analysis of this data along with qualitative community assessment data (described below) will answer Research Aim 4.

Community assessment

In-depth yarning interviews and/or focus groups will assess the local Aboriginal community’s perceptions of sites, and the enablers and barriers to service engagement. Yarning is an accepted culturally informed method of qualitative data collection using semi-structured neutral, open-ended questions that adhere to Aboriginal protocols including the use of stories to develop a relationship between interviewer and interviewee.30 The community assessment may include co-designed quantitative measures to assess service access and responsiveness and narrative based case studies consistent with Aboriginal knowledge systems. Qualitative data will be analysed using thematic content analysis (described above for co-design workshops) to determine culturally nuanced expressions of distress, factors associated with engagement and barriers to access.

Ethics and dissemination

Two documents produced by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia underpin the design of this research: Ethical conduct in research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities: Guidelines for researchers and stakeholders,31 and Keeping Research on Track II: A companion document to Ethical conduct in research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait peoples and Communities: Guidelines for researchers and stakeholders.32

Approvals for the study include the Kimberley Aboriginal Health Planning Forum Kimberley Research Subcommittee, the Western Australian Aboriginal Health Ethics Committee (HREC 955) and reciprocal approval from the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (HRE2020-0023). Ethical and respectful engagement with communities will be guided by the Elder and youth co-researchers, and consideration has been given to the role of caregivers. We have developed safety protocols in the event of participant distress, which reflect the context, needs and local mental health resources. The research team has undertaken training in Aboriginal mental health first aid. Images and video recordings and consent for image use (including cultural considerations) is sought at the initial consent process and prior to images being used.

Dissemination

The active involvement of Elders and young people alongside service staff in co-design will ensure the rapid translation of study outcomes. Their collective involvement through all research stages provides the conditions for knowledge exchange to occur across the sector. Research translation in this study is twofold. First, it will be guided and held by Aboriginal knowledge through the Elders and young people at each site. Second, the translation and dissemination of findings will be designed by participants. This approach ensures the commitment of all stakeholders to implement the findings as well as their ownership of the ensuing process and outcomes.

Work strategically commenced at the Broome site as this is a complex setting with large numbers of Aboriginal young people from the surrounding regions with high needs. Current findings indicate that there are key learnings from Broome headspace, which has as its lead agency the Kimberley Aboriginal Medical Service (headspace is nationally funded and run by a local health service selected through a competitive tender process). The Broome site is unique as it is the only headspace in Western Australia with an Aboriginal Controlled Community Organisation as its lead service or agency. The replication of findings from Broome will be a major focus of the research dissemination and impact activities. This includes working with additional regional sites (provided community consent is given) to replicate effective Broome service access and responsiveness models. In addition, the following activities will be undertaken to ensure broad uptake of the results:

Annual reports, information sheets and newsletters will be distributed to community members and the sector.

A community translation forum will be convened in each site in the final year of the study.

A co-designed media campaign with Aboriginal young people will be undertaken to extend translation impact for Aboriginal young people.

Workshops led by Elder and young co-researchers will be held for policy makers from key organisations including: national Headspace, Aboriginal Health Council of Western Australia, Western Australian Primary Health Alliance, Western Australian Country Health Services, Orygen, Commissioner for Children and Young People Western Australia, the Youth Affairs Council of Western Australia, the Aboriginal Health Council of Western Australia, the Western Australian Mental Health Commission, the Western Australian Department of Health, Department for Child Protection and Family Support, the Western Australian Police Force and Education Department.

The partnership with headspace National and Western Australian headspace centres provides the opportunity to deliver a state network of services with significantly increased ability to meet the needs of Aboriginal young people.

Peer and non-peer reviewed publications will add to the existing body of knowledge.

Seminars will be presented at local and national organisations and universities, and at representative peak organisations to highlight findings and promote their uptake.

Presentations will also be given at relevant local, national and international conferences, and wherever possible, with Elders and young people as co-presenters.

Closed briefings will be provided to state and national politicians and senior executives of mental health services for Aboriginal communities and young people.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MW, AB, PD, RM, JC, GP, AL and EN conceived the research protocol design. MW, HF and EN wrote the first draft. Critical revisions were provided by MW, AB, PD, RM, JC, GP, AL, EN, KKB, MW, AS, NC and HF. All authors contributed to writing the final manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This project is supported by the Australian Government Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) as part of the Million Minds Mental Health Research Mission (MRF1178972). AL is funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Career Development Fellowship (1148793).

Map disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on the map(s) in this article does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. The map(s) are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Moss M, Lee AD. TeaH (Turn ‘em around Healing): a therapeutic model for working with traumatised children on Aboriginal communities. Children Australia 2019;44:55–9. 10.1017/cha.2019.8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salmon M, Skelton F, Thurber KA, et al. Intergenerational and early life influences on the well-being of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children: overview and selected findings from footprints in time, the longitudinal study of Indigenous children. J Dev Orig Health Dis 2019;10:17–23. 10.1017/S204017441800017X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitzpatrick EFM, Macdonald G, Martiniuk ALC, et al. The picture talk project: starting a Conversation with community leaders on research with remote Aboriginal communities of Australia. BMC Med Ethics 2017;18:34. 10.1186/s12910-017-0191-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Donnell M, Taplin S, Marriott R, et al. Infant removals: the need to address the over-representation of Aboriginal infants and community concerns of another 'stolen generation'. Child Abuse Negl 2019;90:88–98. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Commonwealth of Australia . National strategic framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples' mental health and social and emotional wellbeing 2017–2023. Canberra: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2017. https://www.niaa.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/mhsewb-framework_0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Lancet Child Adolescent Health . Suicide in Indigenous youth: an unmitigated crisis. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2019;3:129. 10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30034-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunter E. "Best intentions" lives on: untoward health outcomes of some contemporary initiatives in Indigenous affairs. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2002;36:575–84. 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.01040.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright M, Culbong T, Crisp N, et al. "If you don't speak from the heart, the young mob aren't going to listen at all": An invitation for youth mental health services to engage in new ways of working. Early Interv Psychiatry 2019;13:1506–12. 10.1111/eip.12844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dudgeon P, Milroy H, Walker R, . Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice. 2nd ed. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2014. https://www.telethonkids.org.au/globalassets/media/documents/aboriginal-health/working-together-second-edition/working-together-aboriginal-and-wellbeing-2014.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright M, Lin A, O’Connell M. Humility, inquisitiveness, and openness: key attributes for meaningful engagement with Nyoongar people. Advances in Mental Health 2016;14:82–95. 10.1080/18387357.2016.1173516 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rix EF, Barclay L, Wilson S, et al. Service providers’ perspectives, attitudes and beliefs on health services delivery for Aboriginal people receiving haemodialysis in rural Australia: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003581–10. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coffin J. Rising to the challenge in Aboriginal health by creating cultural security. Aborig Isl Health Work J 200;31:22–4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Commonwealth of Australia . National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health plan 2013-2023. Canberra, 2013. Available: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/B92E980680486C3BCA257BF0001BAF01/$File/health-plan.pdf [Accessed 28 Feb 2021].

- 14.Downing R, Kowal E, Paradies Y. Indigenous cultural training for health workers in Australia. Int J Qual Health Care 2011;23:247–57. 10.1093/intqhc/mzr008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Council of Australian Governments . National Indigenous reform agreement (closing the gap), 2008. Available: https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.federalfinancialrelations.gov.au%2Fcontent%2Fnpa%2Fhealth%2F_archive%2Findigenous-reform%2Fnational-agreement_sept_12.docx [Accessed 28 Feb 2021].

- 16.Australian Government . National Indigenous agency marks a new era of co-design and partnership, 2019. Available: https://ministers.pmc.gov.au/wyatt/2019/national-indigenous-agency-marks-new-era-co-design-and-partnership [Accessed 28 Feb 2021].

- 17.Singer J, Bennett-Levy J, Rotumah D. "You didn't just consult community, you involved us": transformation of a 'top-down' Aboriginal mental health project into a 'bottom-up' community-driven process. Australas Psychiatry 2015;23:614–9. 10.1177/1039856215614985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sherwood J, Edwards T. Decolonisation: a critical step for improving Aboriginal health. Contemp Nurse 2006;22:178–90. 10.5172/conu.2006.22.2.178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright M. Looking forward Aboriginal mental health project final report 2011-2015. Perth, Western Australia: Telethon Kids Institute, 2015. https://waamh.org.au/assets/documents/sector-development/lfp-final-research-report-2015---ecopy.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tuhiwai-Smith L. Decolonizing methodologies: research for Indigenous peoples. 2nd ed. London: Zed Books, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wright M, et al. Building bridges community report 2018. Perth, Western Australia: Curtin University, 2018. https://91cf4966-a774-44ef-8bd3-79a653cb3a77.filesusr.com/ugd/23cdd3_315242bcf6c8405da6861ecb9e972bcd.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 22.Styres SD. Land as first teacher: a philosophical journeying. Reflective Practice 2011;12:717–31. 10.1080/14623943.2011.601083 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chino M, Debruyn L. Building true capacity: Indigenous models for Indigenous communities. Am J Public Health 2006;96:596–9. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.053801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wright M. Research as intervention: engaging silenced voices. Action Learning Action Research Journal 2011;17:25–46. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kovach M. Situating anti-oppressive theories within critical and difference-centred perspectives. : Brown L, Strega S, . Research as resistance: revisiting critical, Indigenous, and Anti-Oppressive approaches. Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholars' Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minkler M, Wallerstein N, . Community-based participatory research for health: from process to outcomes. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dudgeon P, Bray A, Darlaston-Jones D. Aboriginal participatory action research: and Indigenous research methodology strengthening decolonisation and social and emotional wellbeing. Melbourne: The Lowitja Institute, 2020. https://www.lowitja.org.au/page/services/resources/Cultural-and-social-determinants/mental-health/aboriginal-participatory-action-research-an-indigenous-research-methodology-strengthening-decolonisation-and-social-and-emotional-wellbeing [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graneheim UH, Lindgren B-M, Lundman B. Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: a discussion paper. Nurse Educ Today 2017;56:29–34. 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bessarab D, Ng'andu B, Ng’andu B. Yarning about yarning as a legitimate method in Indigenous research. IJCIS 2010;3:37–50. 10.5204/ijcis.v3i1.57 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Health and Medical Research Council . Ethical conduct in research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities: guidelines for researchers and stakeholders. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2018. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/resources/ethical-conduct-research-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples-and-communities [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Health and Medical Research Council . Keeping research on track II: a companion document to ethical conduct in research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities: guidelines for researchers and stakeholders. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2018. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/resources/keeping-research-track-ii [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.