Abstract

Context

Few substance use disorder (SUD) treatment programs provide on-site HIV and/or hepatitis C (HCV) testing, despite evidence that these tests are cost-effective.

Objective

To understand how methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) programs that offer on-site HIV and/or HCV (HIV/HCV) testing have integrated testing services, and the challenges related to offering on-site HIV/HCV testing.

Design

We used the 2014 National Drug Abuse Treatment System Survey to identify outpatient SUD treatment programs that reported offering on-site HIV/HCV testing to ≥75% of their clients. We stratified the sample to identify programs based on combinations of funding source, type of drug treatment offered, and Medicaid managed care arrangements. We conducted semi-structured qualitative interviews with leadership and staff in 2017–2018 using a directed content analysis approach to identify dominant themes.

Setting

Seven MMT programs located in 6 states in the United States.

Participants

Fifteen leadership and staff from seven MMT programs with on-site HIV/HCV testing.

Main Outcome Measure

Themes related to integration of on-site HIV/HCV testing

Results

MMT programs identified three domains related to the integration of HIV/HCV testing on-site at MMT programs: 1) payment and billing, 2) internal and external stakeholders, and 3) medical and SUD treatment coordination. Programs identified the absence of state policies that facilitate medical billing and inconsistent grant funding as major barriers. Testing availability was limited by the frequency at which external organizations could provide services on-site, the reliability of those external relationships, and MMT staffing. Poor electronic health record (EHR) systems and privacy policies that prevent medical information sharing between medical and SUD treatment providers also limited effective care coordination.

Conclusion

Effective and sustainable integration of on-site HIV/HCV testing by MMT programs in the US will require more consistent funding, improved billing options, technical assistance, EHR system enhancement and coordination, and policy changes related to privacy.

Keywords: HIV testing, HCV testing, methadone maintenance treatment, substance use disorder treatment

Introduction

Substance use disorder (SUD) treatment programs provide medication treatment and/or counseling for individuals with SUD. Comprehensive approaches to HIV and HCV prevention, testing and treatment for people who inject drugs (PWID) are critical to address the public health challenge of these infections.1 While SUD treatment programs are appropriate locations for HIV and HCV screening given their high risk populations of PWID, the availability of on-site HIV and HCV testing has been declining over time in the United States. 2–4 In 2017, less than 30% of SUD treatment programs in the US offered HIV testing and HCV testing on-site.5 In comparison to HIV and HCV testing at all SUD treatment programs, a greater proportion of methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) programs provided HIV testing (59%) and HCV testing (63%) on-site.5 MMT programs are highly regulated in the US, with methadone dispensed only in government-certified opioid treatment programs, and state-specific restrictions describing conditions under which patients can take home methadone doses, usually after a defined period of directly-observed treatment.6 MMT has been shown to reduce HIV and HCV risk behavior among patients by reducing injection frequency.7,8

Previous studies of SUD treatment programs in the US identified funding, patient health insurance benefits, and patient and staff acceptability as barriers to offering on-site HIV/HCV testing.9,10 Given the urgent need to address HIV and HCV infection in the current opioid crisis and the declining availability of on-site HIV and HCV testing at SUD treatment programs, we sought to better understand how MMT programs are currently integrating on-site HIV and/or HCV testing into SUD treatment.

Methods

Research team

The research team included health services and clinical researchers, all of whom had prior experience conducting qualitative research. Three investigators (CB, BS, JF) designed the interview guides and each interview was conducted by two out of the three. Two investigators (CB and SK) conducted the qualitative data analysis, with full team discussions to finalize themes. The research team had no pre-existing relationships with interview participants.

Theoretical framework

We based our approach on the Integration of Behavioral Health and Primary Care framework developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which focuses on integrating behavioral health care and medical care.11 The framework takes into consideration care team expertise, clinical workflow, identification of patients in need of integrated health, patient engagement, treatment monitoring, leadership alignment, operational reliability, business model sustainability, data collection, and desired outcomes. Our analysis explores these areas for HIV/HCV testing integration at SUD treatment programs by asking about 1) the testing program characteristics (i.e., HIV and HCV testing practices and process, rapid vs. venipuncture testing, frequency of testing, uptake, and costs), 2) organizational characteristics (i.e., staffing, leadership, clinical space and infrastructure, billing, and electronic health record (EHR) capabilities for tracking testing data), and 3) the external environment (i.e., policies, relationships with external stakeholders, etc.) (Appendix I).

Sampling and data collection

We sampled our participants from the 2014 wave of the National Drug Abuse Treatment System Survey (NDATSS). The NDATSS asks directors and clinical supervisors from a nationally representative sample of U.S. SUD treatment programs to complete an internet-based survey that covered a broad range of topics concerning organizational structures, operating characteristics, and services provided (including HIV and HCV testing) at these programs.3,12 We used the 2014 NDATSS survey to identify inclusion criteria of outpatient SUD treatment programs that reported offering HIV or HCV testing on-site to 75% or more of their clients’ in the past year.

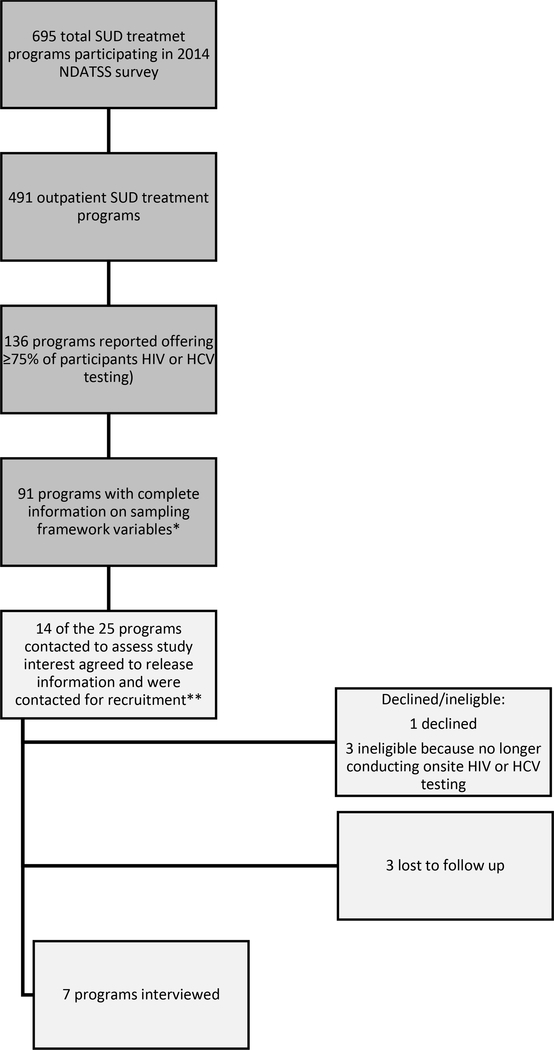

The sampling flow diagram for this qualitative study is described in Figure 1. We sampled to obtain a diversity of programs by using a stratified sampling approach based on the organization type (private for-profit, private not-for-profit, and public), whether the SUD treatment program had a Medicaid managed care arrangement, and whether the program was identified as an opioid treatment program (OTP) offering methadone or buprenorphine treatment. We did not stratify by organization type for non-OTP programs because of a low sample size (N=24) unlike OTPs (N=67). This resulted in 7 sampling strata including 6 OTP program strata and one non-OTP program stratum.

Figure 1. NDATSS Sampling for Outpatient SUD Treatment Programs Offering On-site HIV or HCV Testing to 75% of Patients or more.

*Sampling framework included: opioid treatment program (OTP) status (yes/no); in a Medicaid managed care arrangement (yes/no), and program type (private for profit, private not for profit, and public)

**The 7 sampling categories were the following: 1) Engaged in Medicaid managed care arrangement, non-OTP (1 released information/1 recruited); 2) No Medicaid managed care arrangement, Non-OTP (2 released information/0 recruited); 3) Engaged in Medicaid managed care arrangement, OTP, private for-profit (1 released information/0 recruited); 4) No Medicaid managed care arrangement, OTP, private for-profit (3 released information/2 recruited); 5) Engaged in Medicaid managed care arrangement, OTP, private not-for-profit (1 released information/1 recruited); 6) No Medicaid managed care arrangement, OTP, private not-for-profit (2 released information/1 recruited);7) OTP, public program (4 released information/2 recruited).

Random sampling per strata was adjusted by replacement if the overall sample did not have representation from different regions, Medicaid expansion state status, leadership score (composite score of 8 questions on leadership efforts to learn about developments in SUD treatment; coded as high if equal or above median score and low if below median score),13 and participation in an accountable care organization or patient-centered medical home. Our selection of these inclusion criteria was informed by findings from prior studies on barriers to testing.9,10

Twenty-five programs that fit within the strata criteria were contacted after completion of the 2016 wave of NDATSS to assess interest in the study. A total of 7 MMT programs passed eligibility requirements and agreed to participate; no programs were successfully recruited from the non-OTP stratum but at least one program was successfully recruited from each of the other strata. Programs were offered an honorarium of $750 for the participation of leadership and staff in semi-structured interviews, which were conducted in person or by phone. We interviewed 1–4 people (median=2) at each organization for a total of 15 interviews. We interviewed the HIV/HCV testing program director at all locations and additional staff members as needed to fill in program directors’ knowledge gaps on testing process and funding. We interviewed nursing staff at all 4 locations that provided testing using their own staff and one external program that provided testing for one SUD treatment program. One financial staff person was interviewed to provide additional funding information; program leaders at other locations responded to the financial questions. We did not pursue further sampling once data saturation was reached.

The interview guide included questions that address HIV/HCV testing integration as guided by the conceptual framework (Appendix I). All individual interviews were conducted with two interviewers in person or over the phone. Interviews were recorded when possible (n=11); for unrecorded interviews, detailed notes were taken by both interviewers. Oral consent was obtained from all participants, and the study protocol was approved by the Weill Cornell Medical College Institutional Review Board (IRB) for human subjects’ protections. Interviews were conducted from May 2017 to August 2018 and took on average one hour per interview (maximum: 3 hours).

Data analysis

Transcripts or notes were coded independently by two researchers. We used directed content analysis,14 with a priori codes determined based on a few major domains that encompass the functional domains within the conceptual framework, such as the HIV/HCV testing process characteristics, organizational factors (e.g. billing/payment, internal stakeholders), and local policies related to implementation. We iteratively updated the codebook during data analysis and allowed for inductive codes to emerge outside of our initial structure. Each transcript was then reviewed with the final codebook (Appendix II) to ensure that no new themes emerged. We held regular team meetings during analysis to discuss categorization of codes and emerging themes. All analyses were completed using NVivo Version 11 (QSR International).

Results

Most of the programs (5 out of 7) offered both HIV and HCV testing on-site, one program offered HIV testing only, and one offered HCV testing only. Only one program offered both on-site HIV and HCV treatment; the remaining programs provided treatment referrals. The programs represented a diverse range of regions, organizational funding sources, and sizes (Table 1). Most (5 of 7) were using electronic health records, which emerged as a relevant characteristic in the analysis.

Table 1:

Program Description of Interviewed Methadone Maintenance Programs from NDATSS 2018 Survey

| Program | State | Type of program | Number of Patients Currently Receiving Substance Abuse Treatment | HIV/HCV Testing Status* | Medicaid Managed Care Relationship | Accountable Care Organization or Patient Centered Medical Home Participation | Leadership Score (high leadership vs. low leadership) | Electronic Health Record |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Florida | Private for-profit | 260 | HIV only | yes | No | High | yes |

| 2 | Illinois | Private for-profit | 330 | HIV and HCV testing** | no | No | High | no |

| 3 | Pennsylvania | Private not-for-profit | 214 | HCV only | yes | ACO only | High | yes |

| 4 | Washington | Private not-for-profit | 645 | HIV and HCV testing | yes | No | Low | yes |

| 5 | New Jersey | Private not-for-profit | 116 | HIV and HCV testing | no | No | Low | no |

| 6 | California | Public | 376 | HIV and HCV testing | yes | PCMH only | High | yes |

| 7 | California | Public | 575 | HIV and HCV testing | no | No | High | yes |

ACO = accountable care organization; PCMH = patient-centered medical home

As reported by sites at the time of the interviews

Recently lost onsite testing provider at time of interview; interviews asked about previous recent testing availability

We present results that describe the integration of HIV/HCV testing practices in SUD treatment settings under the following domains: 1) payment and billing, 2) internal and external stakeholders, and 3) medical and SUD treatment coordination.

1. Payment and Billing

Payment and billing for HIV and HCV testing services was the most commonly described barrier to providing HIV and HCV testing on-site at SUD treatment programs. Most programs struggled to cover the costs of testing consistently over time, but they identified a few different ways that they were covering costs. One way that programs covered HIV and HCV testing costs were through patient intake payments, which are bundled payments to SUD treatment programs that cover the costs of a standard patient intake process (i.e., physical exam and screening tests): “Those are mandatory…and that comes out of the pot of money that behavioral health reimburses the laboratories [for intake services].” However, the required intake screening tests differ from state to state, resulting in some programs using intake funds to cover HIV/HCV testing even if not required by state policy and others expressing hesitancy in using those funds for HIV/HCV when not required since this was one of the few sources of income for the organization.

Further limiting the reimbursement options for testing, programs were generally unable to separately bill insurance for HIV and HCV testing services. Billing was limited by state Medicaid policy that maintains medical services and behavior health services (which includes SUD treatment) as separately reimbursed entities:

“Physical health and mental health are carved out, so you’ve got a pot of money for mental health, a pot of money for physical health, and they don’t overlap, so that means only certain services we are able to get reimbursement for and some that you would think we would, but we don’t. Specific aspects of HIV, hepatitis C care, are designated through the physical health side, so we don’t have any say over that and we don’t get reimbursed for certain activities in that area.”

Most programs were receiving government grants or other government funding to provide on-site testing, with the most common source of funding being HIV-specific funding from health departments:

“What happens is historically, the [local jurisdiction] bills as much …as they can for our services and then the rest gets filled in with other sources of funding, which is either some specialty funding like used to be HIV set aside, HIV treatment services money […].The rest gets filled in with general fund [money]…”

However, programs expressed that this form of funding resulted in uncertainty for the sustainability of services over time since these funding streams are short-term and/or one-time opportunities. In fact, several programs reported recently losing government funding. Programs responded to that loss of funding in different ways. Some leaders strongly believed that testing was important and continued to provide testing regardless of funding loss. These organizations absorbed the costs of those tests to cover lab costs: “[HIV testing] went on for at least 10 years, if I’m not mistaken, and then we just integrated it [after funding was lost], because it’s good care. We’ve just been doing it without getting reimbursement for the lab expenses.” One program decided not to continue testing for HIV after their funding loss: “There’s been such a dearth in resources out there to have [HIV testing] on site…so we leave it to making sure that [patients] have a referral to the many resources that I know are available.” In most of these cases though, programs overcame funding barriers through persistence of staff or leadership in finding new grant resources or by partnering with external entities to provide service on-site.

Even for programs that were able to obtain reimbursement for medical services, there were substantial administrative barriers to receiving reimbursement. In some instances, this was due to contracts between the program and a managed care plan. One respondent reported “beating my head bloody on the wall trying to get contracts with Medicaid managed care organizations.” Other regulatory barriers to providing medical services include requiring a license to provide medical care or obtaining state approval to provide rapid testing on-site. In addition, programs that are interested in working more collaboratively with community-based health centers are challenged by the way Medicaid managed care plans assign patients to a primary care provider. The administrative burden of changing the assigned provider may be time consuming. This prevents programs from establishing steady referral relationships with primary care practices:

There are plans to try to work more collaboratively with the federal qualified health centers, but like I said, even if you did, the way it’s structured, when the patient signs up for under [name of Medicaid plan] for behavioral treatment, they’re assigned to us and to an HMO plan designated physician who is in charge of their physical health. Now that physical health provider may not be and more than likely is not in the federal qualified health center.

Despite these challenges, programs still relied on these community-based partnerships to provide on-site testing services.

2. Internal and external stakeholders

Program leaders identified various stakeholders within the organization, such as staff and executive leaders who influenced the culture and organizational motivation for providing HIV/HCV testing on-site. All programs also identified the importance of external stakeholders in helping provide HIV/HCV testing services, either by providing the services on-site or helping acquire funding to support testing.

Staff

Many programs indicated that having enough staff to provide HIV and HCV testing was challenging:

“…it would be nice if we had the capability of a staff person to be able to do the training and the outreach […] but right now, I’m stretched. We’re short-staffed, so I don’t have the resource of a person that could take over...”

To provide testing, the organizations identified a need to train their staff to do pre and post-test counseling and in some cases rapid tests, but this requires sufficient staffing to cover the time required for staff to receive training, which in some cases was lacking in these organizations. In addition to staff availability, there was also concern that a culture of only “treating the addiction” among staff was a barrier to training and expanding staff roles in providing additional non-addiction healthcare services like HIV/HCV testing. “If we could get forward thinking staff, I’d do [testing] in a heartbeat.”

Leadership

Most program directors interviewed were invested in providing HIV and HCV testing on-site, and in several cases provided support to staff members who strongly advocated for testing. Several programs thought that executive leaders of their programs may have some interest in testing, but were driven by competing demands for expanding and improving SUD treatment services:

I can say no, there’s probably not a lot of interest in [HIV and HCV testing]. What [the leadership is] more focused on now is to try and get more referrals for patients because…we’re under census…If the census increases overall and we can demonstrate financial viability, then there may be some interest in focusing in that direction….

In many of these cases where leadership might not prioritize HIV/HCV testing, these organizations expressed a need to improve SUD treatment services first with available funds.

External Stakeholders

Most MMT programs leveraged relationships with external organizations to provide on-site HIV/HCV testing services, but some external relationships were unreliable:

We partner and link with different social services agencies or different agencies that provide their particular services and we allow them to set up on our site. And we try to get as many patients as we can for those particular services. We’ve had a hard time being consistent. We might get a company that comes through for you know one month, five months and then they just kind of drop off the map and then somebody else comes around or we go around and we find another company and then they come in and then they’re here for a while. So yeah that’s been very inconsistent for a while.

Many programs also noted the importance of relationships with health departments for championing HIV and HCV testing. One program was able to leverage its relationship with the local health department to obtain funding for testing when their state HIV funding was cut. Another program noted the changing relationship with the health department over time:

… we used to have very particular people who were champions of our program who were highly placed [in government] and they would find the money. […] A lot of those people are turning over. They’re all getting old and retiring, moving onto other things. […] It’s mostly the philosophical shift where it felt like before we were partners and doing things together, developing programs together, trying things together, writing grants together. And now, it’s like you guys are over there and we’re over here.

Even when programs were providing services using their own staff, external relationships were essential to connecting patients to additional services, such as treatment, housing, and social services.

3. Medical and SUD treatment coordination

Most programs wanted to expand their services to provide more coordinated and comprehensive care for their patients. One of the barriers to providing coordinated care between SUD treatment and medical providers was CFR 42, which is a federal regulation that prevents the sharing of clinical information between substance use providers and medical providers to protect patient confidentiality of their substance use. Several of the MMT programs asked patients to sign a release that allows data sharing between medical and substance use providers in order to facilitate care coordination. However, several program directors identified privacy and confidentiality as important concerns for patients:

[Our patients] have issues too with privacy and confidentiality. They’re afraid that if they access medical care, then they’re going to – you know their insurance company is gonna be made aware that they have a substance use problem. That’s gonna translate into their employer finding out, who pays for their insurance. […] there was a big push in trying to have our patients access Hepatitis C care in the methadone program. But patients wouldn’t do it because of the fear of their employers finding out. They didn’t wanna go through their health insurance because they were afraid that their employers would find out and then there would be some kind of repercussion.

When external organizations provide testing, MMT programs were not notified of testing outcomes because of confidentiality rules; instead, they relied heavily on patient self-report:

Actually, I thought it was a challenge, […] patient records were somewhat confidential, and then for me not knowing whether they had HIV or not and there was a definite issue with certain medications interfering with their methadone dose, and being able to adequately adjust that, and so forth, and like I said, to be honest with you, some of the patients I found out by surprise, like, “Wow, I didn’t know they had HIV.”

Outdated or limited EHR systems at MMT programs and poor communication between EHR systems prevented effective data sharing and tracking of HIV/HCV testing outcomes. A few programs still were using paper charts, “We are very, very behind. We don’t have electronic health records.” Many programs described having very basic EHR systems specifically for SUD treatment. The main way programs documented HIV and HCV outcomes was through free text progress notes, which made it difficult to track testing rates and outcomes at the patient population level. While one program was able to add elements to the existing EHR that would allow for tracking HIV and HCV outcomes, most programs did not foresee being able to improve their EHR in this way.

Discussion and Conclusion

Although some MMT programs have successfully provided on-site HIV/HCV testing, they continue to face uncertainty in reliably and sustainably providing these services. At the root of these issues is a lack of integrated health care payment models.15,16 Instead, SUD treatment programs must spend substantial resources and time on developing, maintaining, and re-establishing external partnerships to ensure reliable delivery of testing services.

Funding and billing capacity was the most frequently discussed challenge to integrating HIV/HCV testing services, primarily because billing is separated between medical care and SUD treatment. Most states have separated behavioral healthcare from physical healthcare delivery, resulting in distinct reimbursement streams, licensure, and regulations that impede integration of care.17 The MMT treatment intake payment, which covers the costs of laboratory testing, offers an opportunity to finance HIV/HCV testing. However, the services covered by the intake payment are determined by state policy, and only some states require HIV/HCV testing. Amending state policies to require the offer of HIV/HCV testing at intake, and to provide sufficient funds to pay for that testing, could alleviate this barrier. Furthermore, health department and federal funding could provide other routes for covering HIV/HCV testing payment at SUD treatment programs, but sustainability of those funds needs to also be addressed. It is also critical to expand the capacity of programs to bill Medicaid and other insurers, but this faces a large systemic barrier in the widespread separation of physical health and behavior health care in the US that would require moving towards more integrated health care payment models. In the near term, programs need to identify other sustainable funding streams to support testing and retesting of this high-risk population in SUD treatment settings.

The culture at many SUD treatment programs reflects their mission to treat addiction first, with secondary or limited interest in comprehensive care.18,19 This study found that both leadership and staff at some programs view HCV/HIV testing as a lower priority compared to SUD treatment. Developing a public health-oriented culture may be one approach to generate staff interest and involvement in providing HIV/HCV testing as part of a comprehensive care approach. Organizations can motivate culture change by setting goals and training staff to view HIV/HCV testing as an essential part of “treating the addiction.” All of the programs demonstrated that program leaders and staff can be empowered as “champions” for HIV/HCV testing. SUD treatment programs may also benefit from technical assistance in developing sustainable approaches to testing by supporting organizational champions. These strategies are being tested in an ongoing clinical trial.20

Previous studies show that SUD treatment programs that are larger and possess medical infrastructure are more likely to provide on-site HIV services,21 but our study identified that even smaller programs can overcome operational challenges by developing relationships with external organizations. Establishing collaborative relationships with local organizations requires investment by program leadership. Our results show, however, that external relationships can be unreliable, leading to gaps in testing availability for patients. Developing incentives for these collaborations may be one strategy for ensuring sustained HIV and HCV testing services over the long term. For instance, pay-for-performance and patient centered medical homes have been used effectively to improve HIV and HCV testing and treatment in other settings.22–24

Finally, integration of HIV and HCV testing services into MMT programs was further limited by policies, regulations, and technology that created obstacles to effectively providing comprehensive, coordinated care. MMT programs need technical assistance and funding to improve the functionality of their EHRs in order to interact with other medical care EHRs and to track non-SUD trends in their patient populations.17 In the US, privacy and confidentiality concerns have motivated separation of data between medical and SUD treatment providers through a federal regulation that protects patient data (CFR 42) and requires a patient to authorize sharing of medical information between providers. However, there is substantial debate about whether this regulation perpetuates stigma by implying that SUD treatment is not a medical condition,25 threatens patient medical safety,26 and creates legal confusion among providers around information sharing.26,27 While these policy debates remain unresolved,28 actions can be taken to educate MMT program staff about how to properly inform their patients of these policies and encourage patients to release information to improve management of their care when appropriate.

There were several limitations to this study. We used the NDATSS survey responses to create a sampling frame based on factors such as Medicaid managed care arrangements and ownership status but found that this did not add substantial insights, since themes were consistent across these sampling categories. Overall, we had a low response rate. To improve recruitment, we considered changing eligibility criteria to include programs that reported offering HIV/HCV testing to >50% of clients instead of >75%, but we found it would not have yielded a substantially larger sample. Our challenges with recruitment revealed that even programs actively testing on-site were struggling with operating and sustaining these services. For example, HIV and HCV testing availability and funding changed frequently for programs, resulting in programs initially eligible for the study no longer being eligible within the time frame that we conducted interviews. For programs that very recently lost funding, we still interviewed the program director to understand testing barriers. We were also only successful in recruiting programs that included MMT in their service offerings despite intending to interview other treatment programs. On-site testing may be important for treatment programs that treat stimulant use where high risk behaviors, such as injecting, increase risk for HIV and HCV 29. Non-OTPs may have been more difficult to recruit because of their focus on behavioral therapies for treating addiction, resulting in less investment and infrastructure for integrating medical services such as HIV/HCV testing. More investigation is warranted to understanding the specific perspectives and constraints faced by non-MMT programs, but our recruitment results suggest that MMT programs may be most engaged and primed for implementing HIV/HCV testing services. Future studies may still consider alternative sampling strategies, such as convenience sampling, to increase the sample size. Lastly, consistent with the goals of qualitative research, our findings provide a rich description of programs’ experience and should not be generalized.

Ultimately, MMT programs faced substantial barriers integrating HIV/HCV testing services, including lack of goal alignment with the primary mission of addressing addiction, human resource limitations, costs,19,30 and a lack of effective approaches for integrating addiction health services and medical care.19,31–33 Even when programs overcame some of these barriers, sustaining onsite HIV/HCV testing services in the future remained uncertain. Further implementation research, technical assistance, and policy change is needed in the US to help MMT programs overcome challenges to adopting HIV/HCV testing strategies20 and provide expanded healthcare access for MMT patients.

Supplementary Material

Implications for Policy and Practice.

Methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) programs face barriers to providing on-site HIV and HCV testing services because of a lack of integrated payment models, resulting in programs spending substantial resources and time on developing, maintaining, and re-establishing external partnerships to ensure reliable delivery of testing services.

Increasing the number of MMT programs that offer on-site HIV and HCV testing and the number of people tested will require consistent funding, improved billing options, technical assistance, enhanced electronic health record systems, and policies that facilitate offering of these services.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Thomas D’Aunno, Peter Friedmann, and Randall Hoskinson who facilitated our work with the National Drug Abuse Treatment System Survey. We also acknowledge and thank the programs that participated in this study for their insight and dedication to this work.

Funding: This research was supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (R01DA027379, P30DA040500, K01DA048172) and the National Institute of Mental Health (T32MH073553). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the funding agencies or the U.S. government.

Conflicts of Interest and Sources of Funding: Dr. Kapadia is an investigator on research grants paid to Weill Cornell Medicine from Gilead Sciences Inc, unrelated to the current work. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. Portions of this paper were presented at a Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine Prevention Science and Methodology Group grand rounds and a New York University Medical School Department of Population Health and Center for Opioid Epidemiology & Policy research seminar.

Footnotes

Human Participant Compliance Statement: The study protocol was approved by the Weill Cornell Medical College Institutional Review Board (IRB) for human subjects protections.

Contributor Information

Czarina N. Behrends, Department of Population Health Sciences, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY, USA.

Shashi N. Kapadia, Department of Population Health Sciences, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY, USA; Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY, USA.

Bruce R. Schackman, Department of Population Health Sciences, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY, USA.

Jemima A. Frimpong, Carey Business School, John Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA..

References

- 1.Perlman DC, Jordan AE. The Syndemic of Opioid Misuse, Overdose, HCV, and HIV: Structural-Level Causes and Interventions. Current HIV/AIDS reports. 2018;15(2):96–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frimpong JA, D’Aunno T, Helleringer S, Metsch LR. Low Rates of Adoption and Implementation of Rapid HIV Testing in Substance Use Disorder Treatment Programs. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;63:46–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Aunno T, Pollack HA, Jiang L, Metsch LR, Friedmann PD. HIV testing in the nation’s opioid treatment programs, 2005–2011: the role of state regulations. Health services research. 2014;49(1):230–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frimpong JA, D’Aunno T, Jiang L. Determinants of the availability of hepatitis C testing services in opioid treatment programs: results from a national study. American journal of public health. 2014;104(6):e75–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sayas A MS, Honermann B, Blumenthal S, Millett G, Jones A. Despite Infectious Disease Outbreaks Linked To Opioid Crisis, Most Substance Abuse Facilities Don’t Test For HIV Or HCV. Health Affairs Blog, October 5, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Addiction in Opioid Treatment Programs.Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 43. DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 05–4048. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karki P, Shrestha R, Huedo-Medina TB, Copenhaver M. The Impact of Methadone Maintenance Treatment on HIV Risk Behaviors among High-Risk Injection Drug Users: A Systematic Review. Evidence-based medicine & public health. 2016;2:e1229. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nolan S, Dias Lima V, Fairbairn N, et al. The impact of methadone maintenance therapy on hepatitis C incidence among illicit drug users. Addiction (Abingdon, England). 2014;109(12):2053–2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bini EJ, Kritz S, Brown LS Jr., Robinson J, Alderson D, Rotrosen J. Barriers to providing health services for HIV/AIDS, hepatitis C virus infection and sexually transmitted infections in substance abuse treatment programs in the United States. Journal of addictive diseases. 2011;30(2):98–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kritz S, Brown LS Jr., Goldsmith RJ, et al. States and substance abuse treatment programs: funding and guidelines for infection-related services. American journal of public health. 2008;98(5):824–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korsen N, Narayanan V, Mercincavage L, et al. Atlas of Integrated Behavioral Health Care Quality Measures. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. June 2013. AHRQ Publication No. 13-IP002-EF. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pollack HA. HIV Counseling and Testing in the Nation’s Outpatient Drug Abuse Treatment System: Results from a National Survey, 1995-2005. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2010;38(4):307–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frimpong JA, D’Aunno T. Hepatitis C testing in substance use disorder treatment: the role of program managers in adoption of testing services. Substance abuse treatment, prevention, and policy. 2016;11:13–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative health research. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hobbs Knutson K Payment for Integrated Care: Challenges and Opportunities. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2017;26(4):829–838. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2017.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stokes J, Struckmann V, Kristensen SR, et al. Towards incentivising integration: A typology of payments for integrated care. Health Policy. 2018;122(9):963–969. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bachrach D, Anthony S, Detty A. State strategies for integrating physical and behavioral health services in a changing Medicaid environment. The Commonwealth Fund, August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guerrero EG, Aarons GA, Palinkas LA. Organizational capacity for service integration in community-based addiction health services. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(4):e40–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hood KB, Robertson AA, Baird-Thomas C. Implementing solutions to barriers to on-site HIV testing in substance abuse treatment: A tale of three facilities. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2014;49:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frimpong JA, D’Aunno T, Perlman DC, et al. On-site bundled rapid HIV/HCV testing in substance use disorder treatment programs: study protocol for a hybrid design randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17(1):117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aletraris L, Roman PM. Provision of onsite HIV Services in Substance Use Disorder Treatment Programs: A Longitudinal Analysis. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2015;57:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Avisar N, Heller Y, Weil C, et al. Multi-disciplinary patient-centered model for the expedited provision of costly therapies in community settings: the case of new medication for hepatitis C. Israel journal of health policy research. 2017;6(1):46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen HJ, Huang N, Chen LS, et al. Does Pay-For-Performance Program Increase Providers Adherence to Guidelines for Managing Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Taiwan? PloS one. 2016;11(8):e0161002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suthar AB, Nagata JM, Nsanzimana S, Barnighausen T, Negussie EK, Doherty MC. Performance-based financing for improving HIV/AIDS service delivery: a systematic review. BMC health services research. 2017;17(1):6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaper E, Padwa H, Urada D, Shoptaw S. Substance use disorder patient privacy and comprehensive care in integrated health care settings. Psychological services. 2016;13(1):105–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell ANC, McCarty D, Rieckmann T, et al. Interpretation and integration of the federal substance use privacy protection rule in integrated health systems: A qualitative analysis. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;97:41–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCarty D, Rieckmann T, Baker RL, McConnell KJ. The Perceived Impact of 42 CFR Part 2 on Coordination and Integration of Care: A Qualitative Analysis. Psychiatric services (Washington, DC). 2017;68(3):245–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. HHS 42 CFR Part 2 Proposed Rule Fact Sheet. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2019/08/22/hhs-42-cfr-part-2-proposed-rule-fact-sheet.html. Published August 22, 2019. Accessed February 5, 2020.

- 29.Rajasingham R, Mimiaga MJ, White JM, Pinkston MM, Baden RP, Mitty JA. A systematic review of behavioral and treatment outcome studies among HIV-infected men who have sex with men who abuse crystal methamphetamine. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2012;26(1):36–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haynes LF, Korte JE, Holmes BE, et al. HIV rapid testing in substance abuse treatment: Implementation following a clinical trial. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2011;34(4):399–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Litwin AH, Soloway I, Gourevitch MN. Integrating Services for Injection Drug Users Infected with Hepatitis C Virus with Methadone Maintenance Treatment: Challenges and Opportunities. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2005;40(Supplement 5):S339–S345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kresina TF, Hoffman K, Lubran R, Clark HW. Integrating hepatitis services into substance abuse treatment programs: new initiatives from SAMHSA. Public health reports (Washington, DC : 1974). 2007;122 Suppl 2:96–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kresina TF, Bruce RD, Lubran R, Clark HW. Integration of viral hepatitis services into opioid treatment programs. Journal of opioid management. 2008;4(6):369–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.