Abstract

Background

The opioid overdose crisis underscores the need for health services among people who use drugs (PWUD) with concurrent pain.

Aims

Investigating the effect of pain on barriers to accessing health services among PWUD.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Settings

A setting of universal access to no-cost medical care in Vancouver, Canada from June 2014 to May 2016.

Participants/Subjects

PWUD who completed at least one study interview.

Methods

Data derived from interviewer-administered questionnaires were used for multivariable generalized linear mixed-effects multiple regression (GLMM) analyses.

Results

Among 1,348 PWUD, 469 (34.8%) reported barriers to accessing health services at least once during the study period. The median average pain severity was 3 (IQR: 0–6) out of 10. A dose-response relationship was observed between greater pain and increased odds of reporting barriers to accessing health services (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]: 1.59, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.15–2.21, p = .005 for mild versus no pain; AOR: 1.76, 95% CI: 1.30–2.37, p < .001 for moderate versus no pain; AOR: 2.55, 95% CI: 1.92–3.37, p < .001 for severe versus no pain). Common barriers included poor treatment by health professionals, socio-structural barriers such as transportation or mobility, and long wait lists or wait times.

Conclusions

Pain may be a significant risk factor associated with increased barriers to accessing health services among PWUD. Attention to pain management may improve access to health services, and reducing barriers to health services may conversely improve pain management and its related risks and harms.

Keywords: Health Services Accessibility, Drug Users, Health Services, Pain, Social Stigma, Substance-Related Disorders

INTRODUCTION

Illicit drug use is associated with a range of health-related harms, such as overdose-related morbidity and mortality, infectious disease transmission (e.g., HIV, hepatitis C), cellulitis and soft tissue infections, and drug-related accidents and injuries (Fischer, Murphy, Rudzinski, & MacPherson, 2016). Pain is also a common concern among people who use drugs (PWUD), which may result in reduced quality of life; increased duration, frequency, and intensity of medical treatment; and increased risk for drug-related harms and risk behaviours such as injecting heroin and other illicit opioids, obtaining diverted pain medication, and subsequent increased risk for overdose (Dassieu, Kabore, Choiniere, Arruda, & Roy, 2019; Voon et al., 2014). As such, timely access to health services is essential for PWUD in order to reduce risks for morbidity and mortality, as well contribute to considerable health care cost savings (Lewer et al., 2020).

Unfortunately, many PWUD experience multiple barriers to accessing health services. Such barriers may include exclusion of PWUD from clinical care guidelines or service mandates; stigma or discrimination related to drug use or complex comorbidities such as mental illness; or structural barriers such as unstable housing or incarceration (Barker, Kerr, Nguyen, Wood, & DeBeck, 2015; Prangnell et al., 2016; L. Wang et al., 2016). As a result, the inability to access health services may lead to more severe and costly health complications and hospital admissions (Lewer et al., 2020).

PWUD who have concurrent pain concerns present a particularly complex subpopulation that may be at even greater risk of experiencing barriers to health services due to the clinical complexity of assessing and managing concurrent pain among individuals actively using substances. The prevalence of chronic non-cancer pain among substance-using populations is considerably higher (estimated to be 48% to 60%) compared to the general population (11% to 19%) (Voon, Karamouzian, & Kerr, 2017). Past research suggests that PWUD who have concurrent pain may be more likely to be denied pain medication, experience stigma due to perceived “drug-seeking,” and self-discharge from or avoid healthcare due to perceived inadequacy of pain management approaches (Biancarelli et al., 2019; Voon et al., 2015). Consequently, they may self-manage pain in ways that pose high risk for morbidity and mortality (e.g., injection drug use, obtaining illicit or diverted opioids from street-based drug markets) (Voon et al., 2014), which is particularly concerning in light of the current crisis of opioid-related overdose mortality (Fischer, Pang, & Tyndall, 2019; Huang, Keyes, & Li, 2018).

Given the high prevalence of pain among PWUD and the potential barriers and consequences that pain may pose for this complex population, we sought to investigate the effect of pain on experiencing barriers to health services in two cohorts of PWUD in Vancouver, Canada. Specifically, we sought to explore whether increasing pain severity was significantly associated with increased barriers to accessing health care services, and what specific barriers to accessing health services were significantly associated with pain, in a setting of universal access to no-cost medical care including a network of primary care clinics that endorse harm reduction.

METHODS

Two ongoing prospective cohort studies of PWUD in Vancouver, Canada were the source of data for this study: the Vancouver Injection Drug Users Study (VIDUS) and the AIDS Care Cohort to evaluate Exposure to Survival Services (ACCESS) (Strathdee et al., 1998). Participants were recruited using community-based methods such as street outreach. Eligibility for the studies required participants to be 18 years of age or older; have injected illicit drugs in the month prior to enrolment (VIDUS) or used an illicit drug other than or in addition to cannabis in the month prior to enrolment (ACCESS); and be HIV-seronegative (VIDUS) or HIV-seropositive (ACCESS). Written informed consent was obtained from participants. The University of British Columbia and Providence Health Care Research Ethics Boards provided ethical approval for these studies.

At baseline and semi-annually, trained study interviewers and research nurses administered questionnaires eliciting data on socio-demographics, drug use patterns, risk behaviours, and health care utilization. As per the prospective cohort study design, participants were encouraged to complete follow-up interviews every six months. While the exact timing of interviews varied for each individual, participants were eligible to return for a follow-up interview so long as at least six months had passed since their last interview. Each follow-up interview lasted approximately two hours and took place in private rooms within a research office located in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside neighbourhood. Participants received $40 (CDN) after each study visit. Data from interviews completed between June 1, 2014 and May 31, 2016 were used for the present study. Missing responses were excluded from the present analyses.

The primary outcome of interest, barriers to accessing health services, was defined using the question: “What barriers to accessing health services have you recently experienced?” and coded as “No barriers” versus an endorsement of any of the following list of barriers: do not have a regular doctor, not taking new patients, limited hours of operation, long wait lists/times, didn’t know where to go, transportation, language barrier, jail/detention/prison, difficulty keeping appointments, restricted to one physician, was treated poorly by health care professional, drug use, look like a drug user, discrimination for being on methadone/Methadose, or other. Participants who endorsed “other” barriers were able to provide an ad-lib response that was recorded by the interviewer, either directly into the computerized questionnaire software or on a paper questionnaire that was later transcribed into the computerized questionnaire software by data entry personnel. The ad-lib responses were compiled as string data that were analysed and categorized by the study authors.

The explanatory variable, average pain severity, was measured at each follow-up interview using the numeric zero-to-ten average past-week pain severity scale of the Brief Pain Inventory (Cleeland & Ryan, 1994) and coded as none (0), mild (1–4), moderate (5–6), or severe (7–10) for the primary analysis. These cut-points were determined based on literature describing optimal cut-points for pain severity scales (Von Korff, Ormel, Keefe, & Dworkin, 1992). Linear trend tests were also performed using average pain severity as a numeric (i.e., non-categorical) variable for the full sample as well as for a sub-analysis restricting the sample to only individuals reporting pain (i.e., average pain severity score ≥ 1).

At each study visit, covariate data were collected via the interviewer-administered questionnaires. The covariates selected for this analysis were identified based on conceptual understanding as well as other research (L. Wang et al., 2016) and included: age (per year older); HIV serostatus (positive versus negative); hepatitis C serostatus (positive versus negative); gender (male versus female or other); ethnicity (white versus other); homelessness (yes versus no); highest education completed (≥ versus < high school completion); incarceration (yes versus no); having attacked, assaulted, or suffered violence (yes versus no); having ever been diagnosed with a mental illness (yes versus no); non-fatal overdose (yes versus no); heroin use (≥ versus < daily); prescription opioid use (≥ versus < daily); cocaine or crack use (≥ versus < daily; collapsed into one variable due to small frequencies when disaggregated); methamphetamine use (≥ versus < daily); and heavy alcohol use (more than four drinks per day or 14 drinks per week for men, or more than three drinks per day or seven drinks per week for women). These covariates pertain to the six months prior to the participant’s interview, unless otherwise noted. Enrolment in methadone maintenance treatment or other addiction treatment was not found to be a statistically significant confounding variable, and was therefore not included.

Pearson’s chi-squared tests and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare categorical and continuous variables, respectively, by the primary outcome of interest (barriers to accessing health services: yes versus no) at the most recent study visit. Generalized linear mixed-effects models (GLMM) with logit link and binomial distribution were then used to investigate the association between pain and barriers to accessing health services (“Fitzmaurcie GM, Laird NM, Ware JH: Applied Longitudi- nal Analysis. New Jersey, John Wiley, 2004,”). To account for random variation and repeated measurements from the participants over time, random intercepts were used. An a-priori-defined model building procedure was used that involved first analyzing bivariable GLMM associations between the explanatory and outcome variables of interest; then constructing a multivariable confounding model using variables that were significant at p≤0.1 in the bivariable analyses (Lang, 2007). All p-values were two-sided and significant associations were defined as p<0.05. The analyses were performed using R version 3.1.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2016).

As a sub-analysis, among individuals reporting any barriers to accessing health services, the frequencies of specific responses to the question “What barriers to accessing health services have you recently experienced?” were categorized and stratified by any pain (i.e., average pain severity ≥1) versus no pain (i.e., average pain severity = 0). Participants responded ad libitum to this question and were able to provide more than one response if desired.

RESULTS

One thousand three hundred forty-eight participants completed at least one study interview between June 2014 and May 2016 and were eligible for inclusion in this analysis. Thirty-eight observations with missing responses to the primary explanatory or outcome variable of interest were excluded. Participants in this sample contributed 4,240 complete observations with a median of four (mean: 3; range: 1–4; interquartile range [IQR]: 3–4) follow-up interview visits.

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the sample at their first interview during the study period. The total study sample was 64.6% male and had a median age of 49 years (IQR: 41–55 years) at the start of the study period. The ethnicities represented in the sample included: White (55.1%); First Nations, Aboriginal, Inuit, or Métis (35.5%); Black-African; Black-Caribbean, or other Black (1.8%); Chinese, South Asian, or other Asian (1.3%); Latin American (1.3%); Other (2.2%); and Not Stated (2.2%). The median average pain severity score at baseline for the total sample was 3 (IQR: 0–6). In total, 469 (34.8%) individuals reported having experienced barriers to accessing health services at least once during the study period, and 1,008 (74.8%) individuals reported an average pain severity of ≥1 at least once during the study period.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics and Unadjusted Odds Ratios of 1348 People Who Use Drugs, Stratified by Recently Experienced Barriers to Accessing Health Service

| Characteristic | Barriers, n = 248 (18%) | No Barriers, n = 1100 (82%) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 47 (39–52) | 49 (42–55) | 0.97 (0.96–0.99) | <.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 153 (61.7) | 718 (65.3) | 0.86 (0.64–1.14) | .287 |

| Female | 95 (38.3) | 382 (34.7) | ||

| HIV serostatus | ||||

| Positive | 105 (42.3) | 485 (44.1) | 0.93 (0.70–1.23) | .615 |

| Negative | 143 (57.7) | 615 (55.9) | ||

| HCV serostatus | ||||

| Positive | 208 (83.9) | 952 (86.5) | 0.81 (0.55–1.18) | .272 |

| Negative | 40 (16.1) | 148 (13.5) | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 146 (58.9) | 601 (54.6) | 1.19 (0.90–1.57) | .226 |

| Other | 102 (41.1) | 499 (45.4) | ||

| Homeless* | ||||

| Yes | 53 (21.4) | 145 (13.2) | 1.78 (1.26–2.53) | .001 |

| No | 195 (78.6) | 952 (86.5) | ||

| ≥High school education | ||||

| Yes | 130 (52.4) | 518 (47.1) | 1.24 (0.94–1.64) | .133 |

| No | 112 (45.2) | 553 (50.3) | ||

| Incarcerated* | ||||

| Yes | 20 (8.1) | 55 (5.0) | 1.66 (0.98–2.83) | .059 |

| No | 228 (91.9) | 1,042 (94.7) | ||

| Victim or instigator of violence* | ||||

| Yes | 53 (21.4) | 114 (10.4) | 2.36 (1.6–3.39) | <.001 |

| No | 194 (78.2) | 986 (89.6) | ||

| Mental illness diagnosis | ||||

| Yes | 163 (65.7) | 674 (61.3) | 1.21 (0.91–1.62) | .192 |

| No | 85 (34.3) | 426 (38.7) | ||

| Enrolled in addiction treatment* | ||||

| Yes | 153 (61.7) | 663 (60.3) | 1.06 (0.8–1.41) | .679 |

| No | 95 (38.3) | 437 (39.7) | ||

| Overdose* | ||||

| Yes | 34 (13.7) | 66 (6.0) | 2.49 (1.60–3.86) | <.001 |

| No | 214 (86.3) | 1,034 (94.0) | ||

| ≥Daily heroin use* | ||||

| Yes | 60 (24.2) | 186 (16.9) | 1.57 (1.13–2.18) | .007 |

| No | 188 (75.8) | 914 (83.1) | ||

| ≥Daily prescription opioid use* | ||||

| Yes | 17 (6.9) | 48 (4.4) | 1.61 (0.91–2.86) | .098 |

| No | 231 (93.1) | 1,052 (95.6) | ||

| ≥Daily cocaine or crack use* | ||||

| Yes | 38 (15.3) | 190 (17.3) | 0.87 (0.59–1.27) | .459 |

| No | 210 (84.7) | 910 (82.7) | ||

| ≥Daily methamphetamine use* | ||||

| Yes | 41 (16.5) | 98 (8.9) | 2.03 (1.37–3.00) | <.001 |

| No | 207 (83.5) | 1,002 (91.1) | ||

| Heavy alcohol use† | ||||

| Yes | 39 (15.7) | 162 (14.7) | 1.08 (0.74–1.58) | .698 |

| No | 209 (84.3) | 936 (85.1) | ||

| Average pain severity*,† | ||||

| ≥1 | 168 (67.7) | 562 (51.1) | 2.01 (1.50–2.69) | <.001 |

| 0 | 80 (32.3) | 538 (48.9) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 5 (0–7) | 1 (0–6) | 1.12 (1.07–1.16) | <.001 |

CI = confidence interval; HCV = hepatitis C virus; IQR = interquartile range.

Denotes activities/events within the 6 months before the participant’s interview.

Denotes activities/events within the week before the participant’s interview.

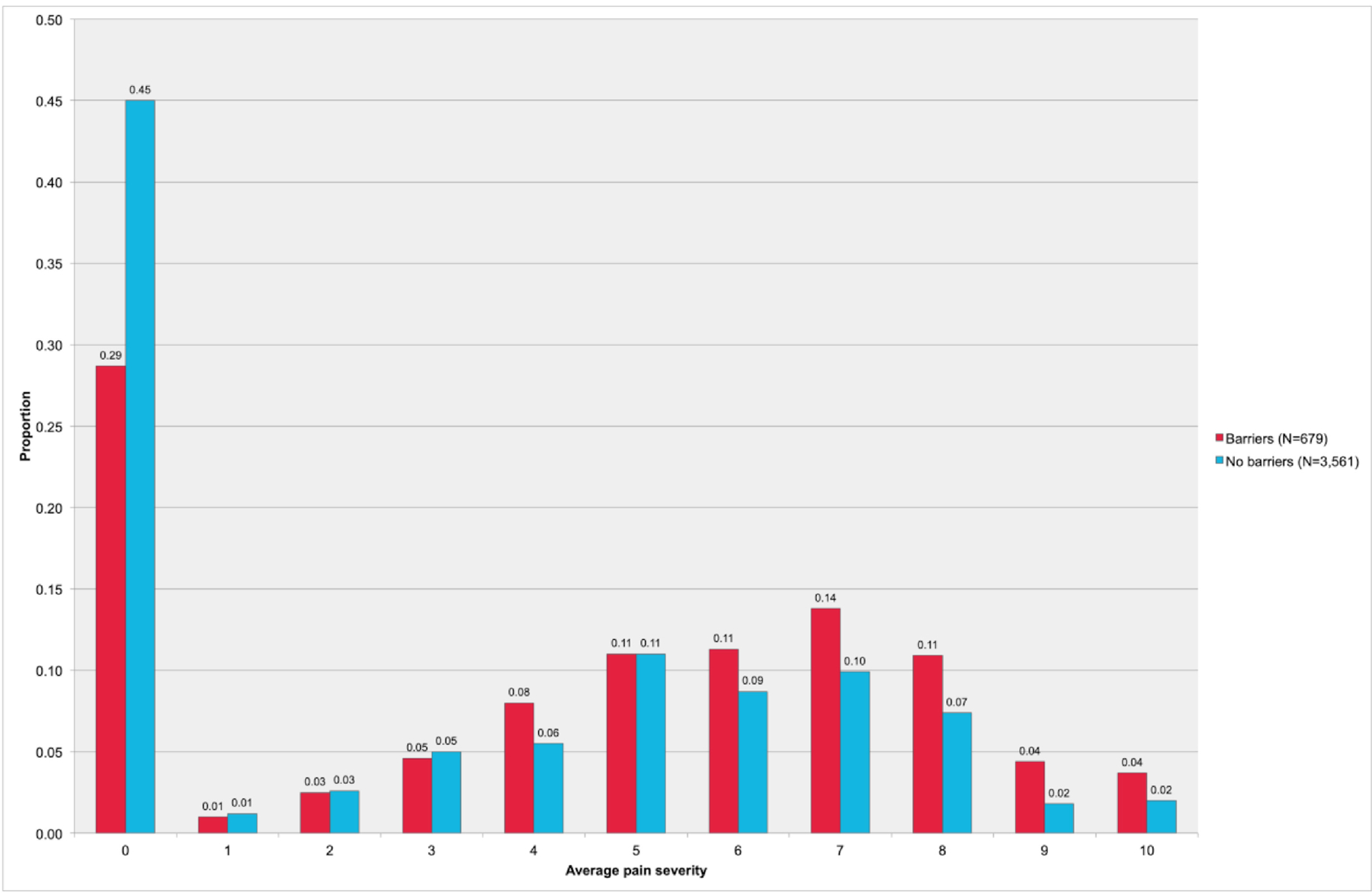

The distributions of average pain severity scores among the total sample and when stratified by barriers to accessing health services are shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. The median average pain severity was significantly higher for observations reporting barriers to accessing health services (median = 5, IQR = 0–7) compared to observations reporting no barriers to accessing health services (median = 1, IQR = 0–6; p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Distribution of average pain severity scores, total sample (n = 1,348 contributing to N = 4,240 observations).

Figure 2.

Distribution of average pain severity scores stratified by barriers to accessing health services (n = 1348 contributing to N = 4,240 observations).

Table 2 shows a dose-response relationship between higher average pain severity and increased odds of reporting barriers to accessing health services. Specifically, the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) of reporting barriers to accessing health services increased from 1.59 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.15–2.21, p = 0.005) to 1.76 (95% CI: 1.30–2.37, p < 0.001) and 2.55 (95% CI: 1.92–3.37, p < 0.001) for mild, moderate, and severe average pain severity, respectively. The trend test using numeric pain severity also showed a significant relationship with barriers to accessing health services in both bivariable and multivariable analyses for the full sample (OR: 1.13, 95% CI: 1.09–1.17, p < 0.001; AOR: 1.13, 95% CI: 1.09–1.17, p < 0.001) as well as for the sub-sample restricted to individuals with pain (OR: 1.10, 95% CI: 1.03–1.17, p = 0.004; AOR: 1.11, 95% CI: 1.04–1.18, p = 0.002).

Table 2.

Bivariable and Multivariable Generalized Linear Mixed Multiple Regression Analyses of Effect of Average Pain Severity on Self-Reported Barriers to Accessing Health Services* Among People Who Use Drugs (n = 1348)

| Average Pain Severity†‡ | Unadjusted | Adjusted* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p Value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p Value | |

| None (reference) | ||||

| Mild (1–4) | 1.83 (1.32–2.54) | <.001 | 1.59 (1.15–2.21) | 0.005 |

| Moderate (5–6) | 1.94 (1.44–2.62) | <.001 | 1.76 (1.30–2.37) | <.001 |

| Severe (7–10) | 2.63 (1.98–3.50) | <.001 | 2.55 (1.92–3.37) | <.001 |

CI = confidence interval.

Adjusted for confounders found to be significant at the level of p ≤ .1 in bivariable analyses (i.e., age, HIV, homelessness, education, incarceration, violence, mental illness, overdose, daily heroin use, daily prescription opioid use, daily methamphetamine use, and heavy alcohol use). Activities/events refer to the 6 months before the participant’s interview.

Average pain severity estimates as a numeric (i.e., noncategorical) variable: unadjusted odds ratio: 1.13; 95% CI: 1.09–1.17; p < .001; adjusted odds ratio (adjusted for same covariates as above adjusted model): 1.13; 95% C: 1.09–1.17; p < .001.

Average pain severity estimates as a numeric variable, restricted to individuals with pain only (i.e., average pain severity score ≥ 1): unadjusted odds ratio: 1.10; 95% CI: 1.03–1.17; p = .004; adjusted odds ratio (adjusted for same covariates as above models except excluding HIV, daily prescription opioid use, and heavy alcohol use, which were not found to be significant at the level of p ≤ .1 in bivariable analyses): 1.11; 95% CI: 1.04–1.18; p = .002.

Table 3 shows the frequencies of specific barriers reported among participants reporting any barriers to accessing health services, stratified by any versus no pain. Barriers to accessing health services were commonly reported at higher frequencies among individuals with pain compared to individuals without pain. Common barriers reported included poor treatment by health professionals (any pain: N=70, 14.5%; no pain: N=11, 5.6%), transportation or mobility issues (any pain: N=62, 12.8%; no pain: N=12, 6.2%), long wait lists or wait times (any pain: N=51, 10.5%; no pain: N=29, 14.9%), difficulty keeping appointments (any pain: N=37, 7.6%; no pain: N=10, 5.1%), mental health related issues (any pain: N=31, 6.4%; no pain: N=16, 8.2%), and not having a regular doctor (any pain: N=28, 5.8%; no pain: N=36, 18.5%).

Table 3.

Barriers to Accessing Health Services Reported by People Who Use Drugs Across 649 Observations, Stratified by Pain*

| Barrier | Any Pain (n = 484) | No Pain (n = 195) |

|---|---|---|

| Treated poorly by health professional | 70 (14.5) | 11 (5.6) |

| Transportation or mobility issues | 62 (12.8) | 12 (6.2) |

| Long wait lists/times | 51 (10.5) | 29 (14.9) |

| Difficulty keeping appointments | 37 (7.6) | 10 (5.1) |

| Mental health-related issues | 31 (6.4) | 16 (8.2) |

| No regular doctor | 28 (5.8) | 36 (18.5) |

| Health care service-related issues | 21 (4.3) | 8 (4.1) |

| Financial/insurance related issues | 20 (4.1) | 14 (7.2) |

| Drug use | 16 (3.3) | 5 (2.6) |

| Physical health-related issues | 16 (3.3) | 4 (2.1) |

| Medication/prescription-related issues | 15 (3.1) | 5 (2.6) |

| Restricted to one physician | 14 (2.9) | 1 (0.5) |

| Not taking new patients | 13 (2.7) | 9 (4.6) |

| Denied care | 12 (2.5) | 2 (1.0) |

| Did not know where to go | 11 (2.3) | 8 (4.1) |

| Limited hours of operation | 11 (2.3) | 7 (3.6) |

| Negative feelings toward health care providers | 11 (2.3) | 5 (2.6) |

| Unable to access specialist | 10 (2.1) | 10 (5.1) |

| Discrimination for being on methadone | 9 (1.9) | 2 (1.0) |

| Look like a drug user | 8 (1.7) | 2 (1.0) |

| Geographical barriers | 5 (1.0) | 4 (2.1) |

| No ID | 5 (1.0) | 4 (2.1) |

| Other | 26 (5.4) | 6 (3.1) |

Restricted to observations in which any barriers to accessing health services in the 6 months before interview were reported. Participants were able to report more than one barrier.

DISCUSSION

Approximately one-third of PWUD in this study reported barriers to accessing health services, and three-quarters reported pain at least once during the study period. A dose-response relationship was observed between greater average pain severity and increased odds of experiencing barriers to accessing health services. This dose-response effect of pain severity remained after controlling for significant confounders that may be related to accessing health services, such as drug use, mental illness, and socio-demographic factors. All intensities of pain (i.e., mild, moderate, and severe) were significantly associated with barriers to accessing health services, as was the non-categorized numeric pain severity variable. Individuals in the highest pain severity categories demonstrated more than double the odds of experiencing barriers to accessing health services compared to individuals reporting no pain. Individuals reporting barriers to accessing health services also had significantly higher median average pain severity scores than individuals reporting no barriers. Collectively, these findings suggest that pain may compromise access to health services among PWUD. Conversely, these findings may suggest that barriers to accessing health services may be associated with increased pain severity among PWUD.

Poor treatment by health professionals was reported as the most common barrier to accessing health services in this study (among individuals reporting any barriers and any pain: N=70, 14.5%; any barriers and no pain: N=11, 5.6%). Substance use is frequently and disproportionately associated with stigma (Yang, Wong, Grivel, & Hasin, 2017), and PWUD who have pain concerns may be particularly prone to negative stereotypes and marginalization. Previous research has described the phenomenon of health providers who may discount requests for pain medication from PWUD as “drug seeking,” which may lead to feelings of stigma or mistreatment and subsequent avoidance of health care or self-management of pain in ways that may pose high risk for morbidity or mortality (Biancarelli et al., 2019; Voon et al., 2015). Alternatively, physiological mechanisms such as withdrawal-related pain or opioid-induced hyperalgesia may contribute to pain intensity (Bluthenthal et al., 2020; Volkow & McLellan, 2016), yet some individuals may be unaware of the potential for such mechanisms to influence pain. Therefore, it is possible that some individuals may perceive that health professionals are treating them poorly with regard to their pain management, when in actuality there may be a complex array of factors with potential to influence the decision-making process of health providers. This underscores the importance of patient-provider communication and education in the context of pain management and mechanisms.

Accessibility barriers such as transportation or mobility issues (any barriers and any pain: N=62, 12.8%; any barriers and no pain: N=12, 6.2%), long wait lists or wait times (any barriers and any pain: N=51, 10.5%; any barriers and no pain: N=29, 14.9%), difficulty keeping appointments (any barriers and any pain: N=37, 7.6%; any barriers and no pain: N=10, 5.1%), and limited hours of operation (any barriers and any pain: N=11, 2.3%; any barriers and no pain: N=7, 3.6%) were also identified as barriers to accessing health care among individuals with pain in this study. Many of these barriers could potentially be related to the physical effects of pain in terms of immobility, disability, or other challenging bio-psychosocial factors associated with pain such as fatigue or distress, which may make basic actions and behaviours required for accessing health services (e.g., waiting for or getting to appointments) difficult for PWUD experiencing pain. Pain disability, defined as the extent to which pain may interfere with an individual’s ability to engage in various life activities (Pollard, 1984), has been described in the general chronic pain population, but little research has been conducted in this area among PWUD. Thus, further research in this area may help to inform strategies to reduce accessibility barriers related to pain among PWUD.

Some individuals with pain in this study reported not having a regular doctor (any barriers and any pain: N=28, 5.8%; any barriers and no pain: N=36, 18.5%), health care service related issues (any pain: N=31, 6.4%; no pain: N=16, 8.2%), drug use (any pain: N=16, 3.3%; no pain: N=5, 2.6%), attending clinics that were not taking new patients (any pain: N=13, 2.7%; no pain: N=9, 4.6%), being denied care (any pain: N=12, 2.5%; no pain: N=2, 1.0%), or not knowing where to go (any pain: N=11, 2.3%; no pain: N=8, 4.1%) as barriers to accessing health services. Concurrent pain and substance use disorders can be clinically challenging to treat, and it may be difficult for PWUD to find health care providers with the willingness and knowledge to treat such complex cases (Edens, Gafni, & Encandela, 2016; Regunath et al., 2016). Such barriers are often systemic and may be related to a lack of services, research, clinical guidelines, and training related to co-occurring pain and addiction, as well as the tendency for pain and addiction to be treated as separate issues by separate disciplines, leading to patients who may encounter difficulties while trying to navigate fragmented health care systems (Edens et al., 2016).

Being restricted to one physician (any pain: N=14, 2.9%; no pain: N=1, 0.5%) was another barrier to accessing health services that was more frequently reported among individuals with pain compared to individuals without pain. In response to the current opioid overdose crisis, prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) are being implemented in many settings in an attempt to reduce prescription opioid diversion and abuse from so-called “doctor shopping,” which is defined as the action of seeking multiple prescriptions from multiple prescribers (J. Wang & Christo, 2009). While PDMPs may be useful in addressing these concerns, such restrictions may also be discriminatory and problematic for individuals with legitimate pain concerns who are not managed appropriately by their existing provider, and subsequently may seek out alternative providers. In fact, there remains a lack of consistent evidence that PDMPs have had any significant effect on rates of opioid-related prescribing, diversion, misuse, or mortality (Finley et al., 2017). Related to this, a previous study involving the current study cohorts found that approximately 6% of participants were denied pain medication due to consulting multiple physicians, and that common actions taken after being denied pain medication included visiting a different doctor or clinic (22%), buying the requested medication off the street (40%), or obtaining heroin (33%) (Voon et al., 2015). In order to mitigate these potential harms, future clinical and policy interventions could be reframed to consider the need to engage, rather than restrict, individuals who access multiple providers (Griggs, Weiner, & Feldman, 2015).

This study has several limitations. First, the self-reported data in this study is susceptible to socially desirable reporting and recall bias. Second, the effect of pain on health service need or uptake could not be ascertained, as the primary outcome compared people who attempted to access health services but faced barriers to both those who did not attempt to access services as well as those who accessed services without barriers. Third, although people with acute or chronic pain may face different barriers to accessing health services, the present analysis did not differentiate between acute and chronic pain, given that both acute and chronic pain may have implications for the ability of PWUD to access health services. Fourth, the covariate related to having experienced violence combined those who had been a victim of violence with those who had been an instigator of violence, yet these experiences may have different associations with barriers to accessing health services. Therefore, the potential for information bias related to this covariate should be noted. Fifth, the associations observed in this study do not provide information on potential causal pathways. Finally, the results of this study may have limited generalizability, particularly given that the present study took place in a setting of universal access to no-cost medical care including a network of primary care clinics that endorse harm reduction. The characteristics of participants in this sample may also limit the generalizability of these findings, as the sample was predominantly comprised of middle-aged white males.

IMPLICATIONS FOR NURSING EDUCATION, PRACTICE AND RESEARCH

These findings highlight several areas for nursing education, practice and research, particularly given the instrumental role of nurses in addressing the current opioid overdose crisis. Attention to pain management in the clinical setting may improve access to health services for PWUD. Conversely, by reducing barriers to health services, nurses may facilitate improved pain management and mitigation of related risks and harms. Possible avenues for reducing barriers to health services may include nursing education, research, clinical practices and policies that aim to: reduce stigma and marginalisation toward PWUD with pain; facilitate patient and provider communication and education related to the complex physiological mechanisms underlying pain among PWUD (e.g., withdrawal, hyperalgesia); improve accessibility of health services (e.g., wait times, hours of operation, physically inclusive spaces); improve coordination of care, service availability, clinical guidelines, and training related to co-occurring pain and addiction; and create solutions to foster patient engagement with health services while mitigating potential risks for individuals who may access multiple health providers.

CONCLUSIONS

In sum, a significant dose-response relationship was observed between increasing pain severity and greater likelihood of reporting barriers to accessing health services in this sample of PWUD. Several barriers were significantly associated with pain, including poor treatment by health professionals and socio-structural barriers related to accessibility of appointments or health providers. These findings demonstrate that pain may be a significant risk factor associated with increased barriers to accessing health services for PWUD or, conversely, that barriers to accessing health services may be significantly associated with greater pain severity. Therefore, attention to pain management may serve to reduce barriers and increase access to health services for PWUD, and reducing barriers to accessing health services may improve pain management among PWUD.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the study participants for their contribution to the research, as well as current and past researchers and staff.

Declarations of Interest

This study was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (U01DA038886 and U01DA021525) and the Canadian In- stitutes of Health Research through the Canadian Research Initia- tive on Substance Misuse (SMNe139148). This research was undertaken, in part, thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs program through a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Inner City Medicine, which supports EW. PV is supported through a Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and a Doctoral Scholarship from The Pierre Elliott Trudeau Foundation. KH is supported by a CIHR New Investigator Award (MSH-141971), a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR) Scholar Award, and the St. Paul’s Hospital Foundation. MJM is supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (U01-DA0251525), a New Investigator award from the Ca- nadian Institutes of Health Research, and a Scholar Award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. He is the Canopy Growth professor of cannabis science at the University of British Columbia, a position established by arms’ length gifts to the uni- versity from Canopy Growth, a licensed producer of cannabis, and the Government of British Columbia’s Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions.

REFERENCES

- Barker B, Kerr T, Nguyen P, Wood E, & DeBeck K (2015). Barriers to health and social services for street-involved youth in a Canadian setting. J Public Health Policy, 36(3), 350–363. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2015.8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biancarelli DL, Biello KB, Childs E, Drainoni M, Salhaney P, Edeza A, … Bazzi AR (2019). Strategies used by people who inject drugs to avoid stigma in healthcare settings. Drug and alcohol dependence, 198, 80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.01.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluthenthal RN, Simpson K, Ceasar RC, Zhao J, Wenger L, & Kral AH (2020). Opioid withdrawal symptoms, frequency, and pain characteristics as correlates of health risk among people who inject drugs. Drug and alcohol dependence, 211, 107932. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.107932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleeland CS, & Ryan KM (1994). Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore, 23(2), 129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dassieu L, Kabore JL, Choiniere M, Arruda N, & Roy E (2019). Chronic pain management among people who use drugs: A health policy challenge in the context of the opioid crisis. The International journal on drug policy, 71, 150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edens EL, Gafni I, & Encandela J (2016). Addiction and Chronic Pain: Training Addiction Psychiatrists. Acad Psychiatry, 40(3), 489–493. doi: 10.1007/s40596-015-0412-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley EP, Garcia A, Rosen K, McGeary D, Pugh MJ, & Potter JS (2017). Evaluating the impact of prescription drug monitoring program implementation: a scoping review. BMC health services research, 17(1), 420. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2354-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer B, Murphy Y, Rudzinski K, & MacPherson D (2016). Illicit drug use and harms, and related interventions and policy in Canada: A narrative review of select key indicators and developments since 2000. The International journal on drug policy, 27, 23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer B, Pang M, & Tyndall M (2019). The opioid death crisis in Canada: crucial lessons for public health. Lancet Public Health, 4(2), e81–e82. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30232-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzmaurcie GM, Laird NM, Ware JH: Applied Longitudi- nal Analysis. New Jersey, John Wiley, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Griggs CA, Weiner SG, & Feldman JA (2015). Prescription drug monitoring programs: examining limitations and future approaches. West J Emerg Med, 16(1), 67–70. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2014.10.24197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Keyes KM, & Li G (2018). Increasing Prescription Opioid and Heroin Overdose Mortality in the United States, 1999–2014: An Age-Period-Cohort Analysis. American journal of public health, 108(1), 131–136. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang T (2007). Documenting research in scientific articles: Guidelines for authors: 3. Reporting multivariate analyses. Chest, 131(2), 628–632. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewer D, Freer J, King E, Larney S, Degenhardt L, Tweed EJ, … Morley KI (2020). Frequency of health-care utilization by adults who use illicit drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction, 115(6), 1011–1023. doi: 10.1111/add.14892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard CA (1984). Preliminary validity study of the pain disability index. Percept Mot Skills, 59(3), 974. doi: 10.2466/pms.1984.59.3.974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prangnell A, Daly-Grafstein B, Dong H, Nolan S, Milloy MJ, Wood E, … Hayashi K (2016). Factors associated with inability to access addiction treatment among people who inject drugs in Vancouver, Canada. Substance abuse treatment, prevention, and policy, 11, 9. doi: 10.1186/s13011-016-0053-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regunath H, Cochran K, Cornell K, Shortridge J, Kim D, Akbar S, … Koller JP (2016). Is It Painful to Manage Chronic Pain? A Cross-Sectional Study of Physicians In-Training in a University Program. Mo Med, 113(1), 72–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Palepu A, Cornelisse PG, Yip B, O’Shaughnessy MV, Montaner JS, … Hogg RS (1998). Barriers to use of free antiretroviral therapy in injection drug users. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association, 280(6), 547–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, & McLellan AT (2016). Opioid Abuse in Chronic Pain--Misconceptions and Mitigation Strategies. The New England journal of medicine, 374(13), 1253–1263. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1507771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, & Dworkin SF (1992). Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain, 50, 133–149. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90154-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voon P, Callon C, Nguyen P, Dobrer S, Montaner J, Wood E, & Kerr T (2014). Self-management of pain among people who inject drugs in Vancouver. Pain management, 4(1), 27–35. doi: 10.2217/pmt.13.62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voon P, Callon C, Nguyen P, Dobrer S, Montaner JS, Wood E, & Kerr T (2015). Denial of prescription analgesia among people who inject drugs in a Canadian setting. Drug and alcohol review, 34(2), 221–228. doi: 10.1111/dar.12226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voon P, Karamouzian M, & Kerr T (2017). Chronic pain and opioid misuse: a review of reviews. Substance abuse treatment, prevention, and policy, 12(1), 36. doi: 10.1186/s13011-017-0120-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, & Christo PJ (2009). The influence of prescription monitoring programs on chronic pain management. Pain Physician, 12(3), 507–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Panagiotoglou D, Min JE, DeBeck K, Milloy MJ, Kerr T, … Nosyk B (2016). Inability to access health and social services associated with mental health among people who inject drugs in a Canadian setting. Drug and alcohol dependence, 168, 22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.08.631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang LH, Wong LY, Grivel MM, & Hasin DS (2017). Stigma and substance use disorders: an international phenomenon. Curr Opin Psychiatry, 30(5), 378–388. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]