Abstract

In March 2020, the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) became a global pandemic that would cause most in-person visits for clinical studies to be put on pause. Coupled with protective stay at home guidelines, clinical research at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ISMMS ADRC) needed to quickly adapt to remain operational and maintain our cohort of research participants. Data collected by the ISMMS ADRC as well as from other NIA AD centers, follows the guidance of the National Alzheimer Coordinating Center (NACC). However, at the start of this pandemic, NACC had no alternative data collection mechanisms that could accommodate these safety guidelines. In order to stay in touch with our cohort and to ensure continued data collection under different stages of quarantine, the ISMMS ADRC redeployed their work force to continue their observational study via telehealth assessment. Based on this experience and that of other centers, NACC was able to create a data collection process to accommodate remote assessment in mid-August. Here we review our experience in filling the gap during this period of isolation and describe the adaptations for clinical research, which informed the national dialogue for conducting dementia research in the age of COVID-19 and beyond.

Keywords: COVID-19, clinical research, Alzheimer disease research center, remote assessment, telephone assessment

Introduction

In early March 2020, a novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19), was quickly becoming a growing concern and was declared a global pandemic1. At that time, there were approximately 153,517 globally confirmed cases, a number that by April 2020 would skyrocket to 1,914,9162,3. Following the declaration of the pandemic, the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital (ISMMS) suddenly halted all in-person human research on March 15th. Due to this decision, coupled with New York’s sudden protective guidelines such as stay at home orders, social distancing, immediate closing of all non-essential businesses, and sheltering in place of all non-essential workers4, clinical research at the Mount Sinai Alzheimer Disease Research Center (ADRC) had to quickly adapt to remain functional. What emerged during this pandemic was a drastically new landscape that the ISMMS ADRC needed to quickly learn to navigate. The aim of this paper is to 1) review the problems that appeared during this uncertain time including changes in workflow and staff responsibilities, 2) present our adaptations for clinical research evaluations during the COVID-19 pandemic, and 3) review the telehealth data collected to fill the void while national data collection methods were unavailable and examine how they compare to previous data collected from the ISMMS ADRC cohort.

Scope of the ADRC Pre-Pandemic

The ISMMS ADRC (P30 AG066514 01, P50 AG005138), an NIA funded research center in operation since 1984, focuses on the study of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias as well as the transition from normal aging to cognitive impairment. The Center is currently organized around seven cores (Administrative, Clinical, Data Management and Statistical Analysis, Genetics and Genomics, Outreach and Education, Neuropathology, and Biomarker Cores) and one component for research education (REC). The Clinical Core performs comprehensive clinical and neuropsychological evaluations using a standardized evaluation to contribute to the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center5. The neuropsychological battery from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center’s Uniform Data Set (NACC UDS) evaluation was developed by the Alzheimer’s Disease Centers (ADC) program of the National Institute on Aging (NIA) for assessing cognitive function and changes over time in older adults. The ADRC coordinates data transfer from the Clinical Core to the Data Management Core and conducts annual longitudinal follow-up of research participants. The Clinical Core also refers participants to other studies and pilot studies, some of which are funded by the National Institutes of Health. The Clinical Core maintains the current cohort of participants with the support of the Outreach and Engagement Core that is tasked with recruiting new participants and retaining them.

In addition to Senior Investigators, the ISMMS ADRC is comprised of 10 Clinical Research Coordinators (CRCs) within the Clinical Core. Each CRC is responsible for managing one of our ADRC clinical trials, including activities such as recruitment, testing, and data submission. Upon first joining the ADRC team, all CRCs receive training and demonstrate proficiency through a certification process in administration of the UDS battery. The battery refers to the domains of cognition most impaired in dementia (i.e., memory, attention, executive function, language, and visuospatial skills) and are strongly correlated with patients’ daily function. These tests require paper, pencils, and a stopwatch and last approximately one hour. The UDS undergoes routine updating of its cognitive assessments5 and as such, routine in service meetings to review changes with all CRCs occurs. This process allows for uniformity in test administration and data collection. Following collection of UDS data through in-person assessment and physician visits, a multidisciplinary team consisting of CRCs, neuropsychologists, clinical dementia experts, and study physicians conduct weekly consensus meetings to determine clinical diagnosis. If a participant has been tested more than once, the team reviews previous data to establish if there has been any change. Following the consensus meeting, a letter of results is mailed to the participant. More advanced cases, not readily available for in-person visits may be assessed by phone through standardized informant interviews about status but do not include cognitive testing6. Table 1 describes the typical UDS clinical tasks of the CRCs and Physicians.

Table 1:

CRC and Physician Clinical Tasks

| CRC Clinical Tasks | Physician Clinical Tasks |

|---|---|

|

|

Research participant records are kept on site at ISMMS either in locked physical storage or on secured network drives. Physical records consist of charts including participant testing results as well as medical records and signed consent forms. Charts are deidentified and stored by participant ID number to allow for easy access when subjects return for their yearly evaluations.

The workflow for Clinical Core evaluations is organized by a central tracking system that provides historical information on cognitive diagnosis staging and prior assessment type. The CRC, and the clinician investigators who are co-located in the same office space determine the plan for participant assessment. This usually includes an in-person visit with the CRC and a clinician.

Methods

Pandemic associated changes: Working Remotely

In order to comply with social distancing and sheltering in place guidelines, as well as to ensure the safety of its workforce, ISMMS encouraged all staff who could complete their work at home, to work remotely. This was made possible by providing resources such as IT support, remote access reference guides, and institutional video conferencing accounts to assist staff in remaining functional while working from home. This allowed the ADRC to develop a safe method to access participant information off campus. Additionally, CRCs all had access to internet, computers, and cameras which made it feasible to work remotely from home.

With IT support from ISMMS, staff at the ADRC was able to quickly learn how to access the virtual private network (VPN). This ensured that information stored in institutional networks onsite could be securely transmitted to CRCs working at home. Additionally, it allowed for CRCs to store collected data to the network, therefore avoiding the risk of losing it.

To support the staff, weekly meetings that were previously held in person were now held over HIPAA compliant video conferencing to maintain social distancing while maximizing connectivity. Additional meetings were scheduled with the full staff to rapidly alleviate any issues that could potentially arise. For example, weekly recruitment meetings were helpful when troubleshooting difficulty reaching a participant and determining the best point of contact. Occasionally, remote meetings were frustrating as they could be repetitive or feel unproductive; however, utilizing the share screen function boosted connectivity and improved productivity and efficiency during meetings.

Workforce Redeployment to Critical Tasks

Most CRCs were responsible for studies and clinical trials in addition to their ADRC Clinical Core activities prior to working remotely. However, most clinical trials requiring in person visits were discontinued. Therefore, staff was reassigned to the longitudinal observational study within the ADRC that collected the Uniform Data Set (UDS)7. The loss of face-to-face connection among the staff required a reorganization of workflow to expedite the planning for assessments. A centralized algorithm was used to determine visit type considering participant severity and previous assessment type. Using the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR) participants with mild or no impairment (CDR 0–1) would be offered a two-stage assessment with remote cognitive assessment and a separate clinician assessment with the participant and study partner. Those with greater impairment would be evaluated by a clinician with the standardized phone interview6 as was the pre-pandemic process. With this decision, the workload of upcoming participants due for an evaluation could be divided among the CRCs and clinicians and communicated via Excel data sheets in which progress could be tracked and stored on a shared network drive. A problem that emerged is that Excel sheets did not allow more than one CRC to edit at a time. To mitigate this issue, a secure, anonymized, document sharing platform was created to track evaluation progress.

Selecting Remote Modalities and a Modified Cognitive Assessment

The ISMMS ADRC needed to identify the best telehealth methods (e.g., telephone or video) to collect cognitive data from elderly participants. Several factors led to the choice of phone testing over video. First, it was determined that relying solely on an available internet connection and video devices could leave some participants unfairly ineligible for testing. Additionally, speech delays, common with internet connectivity could compromise the participant’s ability to accurately hear certain tasks as well as interfere with timed tasks. Therefore, telephone testing was optimal to video testing.

However, modifying in person testing to be conducted over the telephone presented challenges. ISMMS ADRC Core leaders met daily to modify the tests administered in the UDS. As there could be no visual or writing/drawings components, test tasks needed to be omitted or modified. There were multiple training sessions with neuropsychologists and CRCs to review changes and avoid potential issues during remote testing. Additionally, UDS data is collected utilizing paper and pencil methods. Printing multiple packets, consisting of hundreds of pages, for staff to take home or mailing packets home to staff, while a quick solution, was time consuming and costly. An improved solution was to digitize data collection packets into an editable PDF so that all CRCs had access to packets on their computers from home. Creating an editable PDF required multiple rounds of formatting and testing and utilizing feedback from CRCs to ensure usability and functionality.

Maximize Participant Comfort with Remote Assessment

With the increase of scam phone calls and the vulnerability of seniors with cognitive issues8, it was important to create trusted communication channels while working remotely and calling from new, unidentified phone numbers. If CRCs needed to leave a voicemail for a participant, they included both their personal cell phone number and the ISMMS ADRC main line number. Occasionally, there were instances in which participants relied on prepaid minutes for cellphone use and did not want to utilize all their minutes for an hour-long cognitive assessment. In these instances, services such as internet-based phone applications were utilized which allowed for free voice calling through their phone’s internet connection rather than the cellular plan’s voice minutes.

Preparing the Participant for Remote Cognitive Testing

Because remote testing would occur in the participant’s home, a standard operating procedure (SOP) was developed to maximize good testing conditions and test reliability. CRCs asked standardized set of questions to each participant to ensure testing conditions were quiet, and sufficiently private, to allow them to focus and reduce interruptions. Participants were asked to turn off electronic devices (e.g., radio, television, etc.) and to ask other household members to not assist during the testing. Once participants agreed to assessment over the phone and were in a quiet and private place, the issue of how to adequately engage seniors in telehealth assessment emerged. Telephone assessment is not as engaging as in person assessment. For example, while pauses during telephone conversation are expected during in person conversation, during telephone assessment pauses in conversation needed to be reduced to maintain the same level of engagement and maximize communication. In person conversation relies on not only verbal communication, but nonverbal communication as well. On the phone, these types of cues are restricted, therefore CRCs were expected to talk through each aspect of the assessment and check in with the participant to ensure that they were comfortable, engaged, and understood all tasks. It required CRCs to develop a new awareness of when a pause in conversation was too long and how to determine if participants were attentive (e.g., ask participants questions to ensure understanding).

Remote Clinician’s Visit

In addition to cognitive testing, participants meet face-to-face with a physician as a part of their yearly visit with the ISMMS ADRC. However, due to similar constraints as described above, clinician visits were primarily completed over the phone using an adaptation of the UDS clinician instruments5. For cognitively intact participants or those with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), the interview included reviewing memory concerns, exploring medical and neurological review of systems and assessing for psychiatric symptoms, particularly depression, in the context of social isolation associated with the pandemic. There were limitations with conducting the neurologic exam via the telephone. For example, vital signs could not be obtained (e.g., blood pressure) nor could gait be assessed. Therefore, neurologic symptoms were assessed by focused questioning about tremors, focal weakness, changes in gait, falls or neuropathy. For subjects with dementia, a brief interview with the participants when available and then a more comprehensive interview with the informants was performed. In addition, a brief survey of caregiver stress and coping strategies was administered to identify those who would benefit from outreach from our social worker. This interview format with patients with dementia was utilized prior to the pandemic and was expanded upon to meet the needs of participants and physicians during COVID-19. In the handful of cases where video conferencing technologies were available, a modified neurologic exam assessing for tremors, and observing gait was performed.

Virtual Diagnostic Consensus Meetings

Consensus meetings were typically held several times per week in-person and needed to be amended to facilitate a working from home environment. An online document that did not include identifying information was created. The online document could be accessed by all staff remotely and included the CRC responsible for the case, their subject number, visit date, submission for consensus date, date of consensus, and any relevant comments.

During consensus, any previous data that was collected at earlier visits and kept in physical charts, had also been submitted to the National Alzheimer Coordinating Center (NACC). Therefore, any prior data that was needed for comparison could be downloaded from the NACC website as it was not available physically while working remotely. CRCs were responsible for downloading necessary material and providing it for consensus meeting when preparing the case for review.

Following consensus meetings, in order to share results with the participant, with their permission, participant results were sent over secure email. Email addresses were verified at the time of the assessment. If a participant did not have an email address, results could be emailed to the study partner, with the participant’s permission.

Results

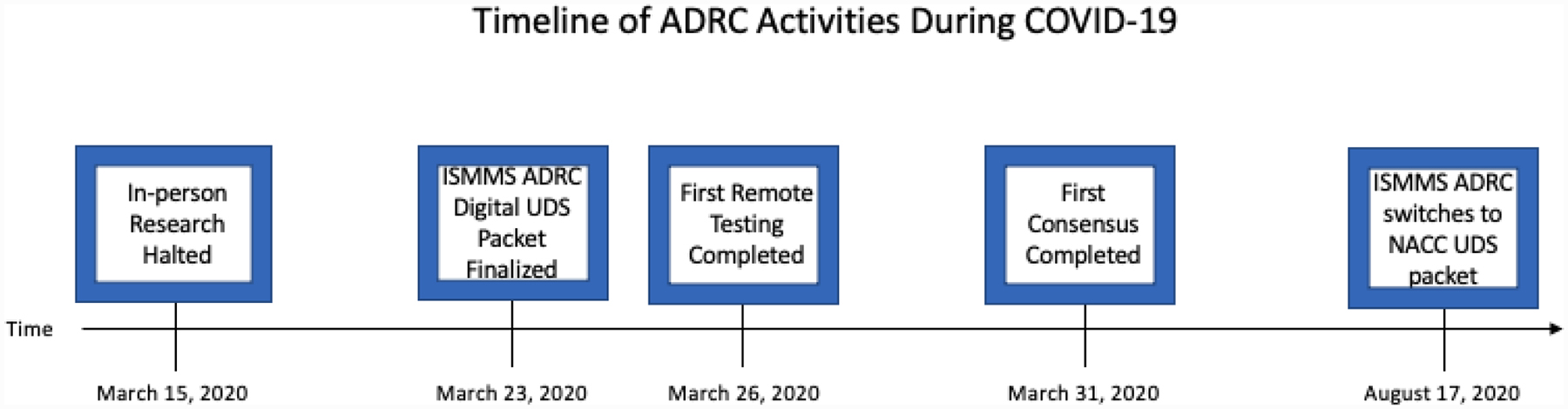

Figure 1 depicts the timeline of ADRC activities during COVID-19, from initial restriction to the availability of standardized remote data collection tool from NACC. On March 15th, in-person research was halted by ISMMS. Eight days later on March 23rd, a digitized version of the UDS assessment packet was finalized by the ISMMS ADRC team as national collection methods were unavailable, on March 26th the first remote testing was completed, and on March 31st, 16 days following research being halted, the first consensus meeting was completed. These results will focus on the first 152 cases completed between March and August by the ISMMS ADRC, while NACC testing materials were still being prepared.

Figure 1:

Timeline of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ISMMS ADRC) activities during coronavirus (COVID)-19. NACC UDS indicates National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center’s Uniform Data Set.

Table 2 depicts the demographic characteristics of the total ISMMS ADRC cohort, those that were approached for telehealth, those that agreed to participate in telehealth testing, and those that declined to participate. We attempted to approach 152 participants for telehealth, 10 could not be reached; of those, 30% identified as Black, 30% identified as Hispanic, and 40% identified as White. A total of 35 participants declined to participate in remote testing. The ISMMS ADRC cohort is approximately 58% female, with females comprising 70% of those approached for telehealth as well as agreed to participate in telehealth assessment. A majority of the ADRC cohort have a CDR score of 0 (57%) or 0.5 (23%) and this trend is similar across groups. The ADRC cohort is diverse, with close to fifty percent of the cohort comprised of minority groups (48%). Of those that were approached for telehealth, 40% of participants were comprised of minority groups, while of those that agreed to participate in telehealth 35% of participants were comprised of minority groups, and of those that declined telehealth assessment, 57% of participants were comprised of minority groups.

Table 2:

Demographics of Total ISMMS ADRC Cohort and those that were approached for telehealth

| Characteristic | Total ISMMS ADRC Cohort (N = 410) |

Approached for Telehealth (N = 152) |

Agreed to Telehealth (n = 117) |

Declined Telehealth (n = 35) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (%) | ||||

| Female | 57.94 | 70.39 | 70.08 | 71.43 |

| Male | 42.06 | 29.61 | 29.91 | 28.57 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 76.65 (8.81) | 76.80 (8.52) | 76.80 (9.06) | 76.80 (6.47) |

| Education, mean (SD) | 15.02 (3.80) | 15.08 (4.11) | 15.16 (4.05) | 14.83 (4.36) |

| Race (%) | ||||

| White | 51.64 | 59.21 | 64.10 | 42.86 |

| Black | 17.29 | 10.53 | 7.70 | 20.00 |

| Hispanic | 24.30 | 26.97 | 24.79 | 34.29 |

| Asian | 4.91 | 1.32 | 0.85 | 2.86 |

| Other | 1.87 | 1.97 | 2.56 | 0 |

| Diagnosis (%) | ||||

| Cognitively Normal | 60.98 | 62.50 | 55.56 | 85.71 |

| MCI | 17.07 | 12.50 | 13.68 | 8.57 |

| AD | 21.95 | 25.00 | 30.77 | 5.71 |

| CDR (%) | ||||

| 0 | 57.71 | 60.53 | 54.70 | 80.00 |

| 0.5 | 23.36 | 17.11 | 17.09 | 17.14 |

| 1.0 | 7.48 | 6.58 | 8.55 | 0 |

| 2.0 | 5.61 | 8.55 | 10.26 | 2.86 |

| 3.0 | 5.84 | 7.24 | 9.40 | 0 |

Table 3 depicts telehealth testing results compared to in-person testing within the ISMMS ADRC cohort by diagnosis. The CDR yields a Sum of Boxes (SOB) score which is used to accurately stage severity of Alzheimer dementia and MCI. Average SOB score was 0.06 (SD = 0.22) for cognitively Normal, 1.96 (SD = 2.71) for MCI, and 11.06 (SD = 5.41) for AD within the telehealth cohort. Within the total ADRC cohort the average SOB score was 0.07 (SD = 0.21) for cognitively Normal, 1.28 (SD = 0.90) for MCI, and 9.89 (SD = 5.54) for AD. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is a screening assessment used for detecting cognitive impairment. The MoCA total correct score is 30 points; however, several items needed to be omitted for phone evaluations, thus the telehealth MoCA total correct score was 21 points. The average MoCA score was 82% correct for cognitively Normal, 68% for MCI, and 44% correct for AD within the telehealth cohort, and similar to the total ADRC cohort. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI) is an instrument that measures the presence and severity of a range of neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia. The average NPI score was 1.33 (SD = 2.78) for cognitively Normal, 5.14 (SD = 4.50) for MCI, and 6.91 (SD = 4.69) for AD within the telehealth cohort. Within the total ADRC cohort the average NPI score was 1.09 (SD = 2.59) for cognitively Normal, 2.39 (SD = 2.83) for MCI, and 5.14 (SD = 4.30) for AD.

Table 3:

Telehealth testing results compared to in-person testing within the ISMMS ADRC cohort divided by diagnosis

| Telehealth Cohort | Total ISMMS ADRC Cohort | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Testing M (SD) | Normal (55%) |

MCI (14%) |

AD (31%) |

Normal (58%) |

MCI (16%) |

AD (21%) |

| SOB | 0.06 (0.22) | 1.96 (2.71) | 11.06 (5.41) | 0.07 (0.21) | 1.28 (0.90) | 9.89 (5.54) |

| MoCA (% Correct) | 82* | 68* | 51* | 82 | 68 | 44 |

| NPI | 1.33 (2.78) | 5.14 (4.50) | 6.91 (4.69) | 1.09 (2.59) | 2.39 (2.83) | 5.14 (4.30) |

Note: for telehealth administration purposes, the MoCA was out of a maximum 21 points

Discussion

In this paper we describe the process of transitioning the ISMMS ADRC clinical core evaluation from in person to remote assessment. The transition was a complex team effort which included the rapid preparation of a telehealth battery in the 8 days following the halting of in-person research by the IRB (March 15th) and creation of systems to ensure maximum functionality while safely working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic. This resulted in a total of 117 completed cases in 155 days by August 17th, when the NACC created a new national standard approach which our experiences helped shape.

There are a multitude of factors that allowed for such a rapid and efficient transition of the ISMMS ADRC’s transition to working remotely. First, institutional support for IT provided the tools necessary to successfully work remotely without disrupting workflow or causing unnecessary delays. IRB flexibility allowed for assessment to be conducted over the telephone despite the initial protocol being developed for in person assessment. Additionally, the ISMMS ADRC’s common training protocol for the UDS across all CRCs allowed for an even distribution of tasks and permitted deployment to other duties. Remote assessment could not be completed without creating high acceptability among participants. This included paying careful attention to already established trusted relationships between CRCs and participants to build confidence in the communication modality selected. The use of the telephone for assessment rather than video conferencing and the flexibility to collect data via multiple phone services (e.g., utilizing an internet-based phone application, land line, etc.) maximized the diversity of the cohort which could be engaged. Using telephonic assessments also aided participant acceptance of the assessments, as all were familiar with this modality and time was not lost in training many participants in novel modalities. During this period of working from home, the flexibility and commitment of staff to learn remote assessment and adapt to new digitized forms as well as finding creative ways to contact and engage seniors was paramount to the success of the ISMMS ADRC.

While we were able to assess both normal and mildly impaired participants, there were some other differences between the overall ISMMS ADRC and the telehealth cohort. First, among those that could not be reached, a large portion (60%) were part of a minority group. While diversity was maintained in those who underwent remote assessment, it was a lower percentage than in our full cohort, particularly among those identified as Black. One possible reason for this may be the reported disproportionate effect of COVID-19 in Black communities9–11. This could result in change in living situation making contact more difficult, and therefore unable to effectively approach. A similar but smaller trend is noted among the Hispanic participants.

Second, when considering the total sample of those that agreed to telehealth assessment with other notable telehealth studies in the field, it is clear that remote assessment can be conducted with a wide range of groups including those who are diverse12. For example, approximately 41% of participants that were approached for telehealth assessment self-identified as being part of a minority group. Of the group of participants that agreed to telehealth, approximately 36% of participants self-identified as being part of a minority group. This indicates that diverse participants can not only transition from in person testing to telehealth testing, but transition during a stressful period of time.

In reviewing test results, several patterns are notable between the total ISMMS ADRC cohort and the telehealth cohort. While we were unable to capture cognitive performance via telehealth equivalently to in person testing (e.g., unable to conduct visually mediated tasks), most testing results were similar. One exception was performance on the NPI. The NPI scores were higher across all diagnostic categories within the telehealth cohort when compared to the total ISMMS ADRC cohort indicating increased behavioral symptoms, suggesting that participants are being negatively affected during the COVID-19 pandemic, which is consistent with the report of distress around the pandemic13. Additionally, while social isolation is the most effective tool in preventing the spread of COVID-1914, this practice can have a disproportionately negative impact on behavioral symptoms older adults15.

Future Implications and Limitations

The utilization of telehealth assessment allowed for mechanisms of follow up in time of unforeseen events such as COVID-1916. It may also have potential advantages over traditional in-person assessments, by reducing burden of travel and inconvenience of in-clinic evaluations such as wait times. While preference was not addressed in the current study, one multi-site study of Home-Based Assessment found healthy, older participants, reported dissatisfaction in not seeing staff and other participants17. This may differ among those with cognitive impairment particularly if they are dependent on study partners to attend visits. Additionally, while several studies have indicated that remote assessment measures have equal sensitivity to in-person assessment measures18–20, this does not mean that they are equivalent. Although many domains can be assessed, and a diagnosis can be determined, we cannot yet determine that telehealth assessment scores are comparable to in-person assessment. Patients with hearing loss may not be appropriate candidates for telehealth as testing depends on hearing the prompts from the examiner. Another limitation of telehealth testing includes the telehealth neuro exam in which aspects of the physical face-to-face exam (e.g., measuring vital signs, assessing for gait and tremor) do not translate readily to a remote medium. Finally, telehealth testing reduces the ability to collect biomarkers, an outcome measure often utilized in clinical trials.

Conclusions and Considerations

Telehealth assessment provided a viable means to conducted follow up during the COVID19 pandemic. Continued follow-up will need to be conducted to clarify the advantages and disadvantages of remote assessment. Acceptability for not only participants but for staff as well has to be weighed in the context of broad potential psychological stress during an ongoing pandemic.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute On Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32AG066598. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(1):157–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report-55. 2020.

- 3.World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report-86. 2020.

- 4.Government NYS. New York State on Pause 10 Point Plan. https://coronavirus.health.ny.gov/new-york-state-pause. Published 2020. Accessed.

- 5.Morris JC, Weintraub S, Chui HC, et al. The Uniform Data Set (UDS): clinical and cognitive variables and descriptive data from Alzheimer Disease Centers. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20(4):210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.NACC. NACC Uniform Data Set Telephone Follow-Up Packet. Published 2020. Accessed2020.

- 7.Weintraub S, Salmon D, Mercaldo N, et al. The Alzheimer’s Disease Centers’ Uniform Data Set (UDS): the neuropsychologic test battery. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23(2):91–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.James BD, Boyle PA, Bennett DA. Correlates of Susceptibility to Scams in Older Adults Without Dementia. Journal of elder abuse & neglect. 2014;26(2):107–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. Jama. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim SJ, Bostwick W. Social Vulnerability and Racial Inequality in COVID-19 Deaths in Chicago. Health education & behavior. 2020;47(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sood L, Sood V. Being African American and rural: a double jeopardy from Covid-19. The Journal of Rural Health. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sano M, Zhu CW, Kaye J, et al. A randomized clinical trial to evaluate home-based assessment of people over 75 years old. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2019;15(5):615–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Globalization and health. 2020;16(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferguson N, Laydon D, Nedjati-Gilani G, et al. Report 9: Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID19 mortality and healthcare demand. Imperial College London. 2020;10:77482. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perissinotto C, Holt-Lunstad J, Periyakoil VS, Covinsky K. A practical approach to assessing and mitigating loneliness and isolation in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2019;67(4):657–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicol GE, Piccirillo JF, Mulsant BH, Lenze EJ. Action at a Distance: Geriatric Research during a Pandemic. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(5):922–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sano M, Egelko S, Zhu CW, et al. Participant satisfaction with dementia prevention research: Results from Home-Based Assessment trial. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(11):1397–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buckley RF, Sparks KP, Papp KV, et al. Computerized Cognitive Testing for Use in Clinical Trials: A Comparison of the NIH Toolbox and Cogstate C3 Batteries. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2017;4(1):3–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jongstra S, Wijsman LW, Cachucho R, Hoevenaar-Blom MP, Mooijaart SP, Richard E. Cognitive Testing in People at Increased Risk of Dementia Using a Smartphone App: The iVitality Proof-of-Principle Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2017;5(5):e68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rentz DM, Dekhtyar M, Sherman J, et al. The Feasibility of At-Home iPad Cognitive Testing For Use in Clinical Trials. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2016;3(1):8–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]