Abstract

Longitudinal cohort studies present unique methodological challenges, especially when they focus on vulnerable populations, such as pregnant women. The purpose of this review is to synthesize the existing knowledge on recruitment and retention (RR) of pregnant women in birth cohort studies and to make recommendations for researchers to improve research engagement of this population. A scoping review and content analysis were conducted to identify facilitators and barriers to the RR of pregnant women in cohort studies. The search retrieved 574 articles, with 38 meeting eligibility criteria and focused on RR among English-speaking, adult women, who are pregnant or in early postpartum period, enrolled in birth cohort studies. Selected studies were birth cohort (including longitudinal) (n=20), feasibility (n=14), and other (n=4) non-interventional study designs. The majority were from low-risk populations. Abstracted data were coded according to emergent theme clusters. The majority of abstracted data (79%) focused on recruitment practices, with only 21% addressing retention strategies. Overall, facilitators were reported more often (75%) than barriers (25%). Building trusting relationships and employing diverse recruitment methods emerged as major recruitment facilitators; major barriers included heterogeneous participant reasons for refusal and cultural factors. Key retention facilitators included flexibility with scheduling, frequent communication, and culturally sensitive practices, whereas participant factors such as loss of interest, pregnancy loss, relocation, multiple caregiver shifts, and substance use/psychiatric problems were cited as major barriers. Better understanding of facilitators and barriers of RR can help enhance the internal and external validity of future birth/pre-birth cohorts. Strategies presented in this review can help inform investigators and funding agencies of best practices for RR of pregnant women in longitudinal studies.

Keywords: Pregnant women, birth cohort, recruitment, retention, facilitators, barriers

1. Introduction

Longitudinal studies tracking child development since birth or even during the fetal stage can provide an optimal window into life course development. Prospective birth cohort studies have historically been used to answer basic questions relative to child development and human behavioral teratology. Since the prenatal period presents one of the most important and vulnerable stages of fetal development, accurate characterization of maternal environment and environmental exposures during this period is crucial in understanding long-term pediatric developmental outcomes. Although prospective cohort studies assess the development of older children, such as the ABCD study (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2021) that is focused on children ages 9–10 years and follows them into adulthood, there is a scarcity of long-term, large-scale studies on younger children, especially those that begin with in-utero assessments. While the pregnant woman is the focus of recruitment and retention in this review, it is recognized that approaches that are successful will account for the fact that the mother is participating both while pregnant and with and on behalf of her child after delivery.

In the context of the Barker hypothesis also known as the developmental origins of health and diseases, intrauterine environment and perinatal factors play a crucial role in the programming of key physiological processes influencing the future development of adult-onset disorders (Calkins & Devaskar, 2011). Epigenetic changes during these crucial periods of child development are thought to be key mechanisms for susceptibility to chronic diseases later in life (Lunde et al., 2016). As a result, characterization of pre- and perinatal factors is paramount for longitudinal studies tracking child development over time. While some indirect assessment of prenatal exposures and environment is feasible after birth, recruitment during pregnancy is less prone to recall bias and often allows incorporation of prospective repeated objective measures, such as physiological and biological indices in addition to maternal self-report. Thus, contemporaneous assessment of the prenatal environment by initiating recruitment during pregnancy is preferable notwithstanding substantial challenges associated with recruitment and longitudinal follow-up of maternal-infant dyads.

Although research involving pregnant women and environmental perturbations in utero that can impact future child development are needed, pregnant women remain underrepresented in clinical research studies. However, involving pregnant women in research presents a unique opportunity to examine the effects of maternal health behaviors as well as other factors in the prenatal environment and their effect on short and long-term child outcomes. This underrepresentation of pregnant women in studies has been partially due to concerns of research impacting not only the woman, but also a vulnerable fetus. In the past, federal regulations classified pregnant women, regardless of their overall health or legal status, as a vulnerable population (Lyerly et al., 2008).

Through a meta-analysis of the literature, Van der Zande et al. (2017) explored to what extent pregnant women are a vulnerable population. The authors found that the vulnerability of pregnant women is largely attributable to the lack of scientific knowledge about this class of individuals, which further illustrates the importance of including this underrepresented population when conducting research. To that end, the recently revised federal policy for the protection of human subjects, 45 CFR 46 (Subpart B), outlines specific protections for pregnant women involved in research (Office for Human Research Protections, 2018a). These regulations have removed pregnant women as a class from the list of those categorized as vulnerable (Office for Human Research Protections, 2018b). Furthermore, guidance has been recently drafted by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the ethical inclusion of pregnant women in clinical trials (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018). Information about retention of children – another vulnerable group, is even more scarce. While some strategies have been identified for retention of children recruited into intervention studies in community settings, e.g., optimizing consent and follow-up procedures, offering appropriate incentives to children and parents, and minimizing participant burden (Schoeppe et al., 2014), those strategies typically apply to older children who are able to give assent for participation.

Of particular concern in observational longitudinal studies is the risk of selection bias, which can compromise internal validity, due to self-selection of participants and differential losses to follow-up in which subjects that are recruited and retained in the cohort are systematically different from non-participants and drop-outs and are not representative of the population. Despite concerted efforts for inclusion of women, children, and ethnic minorities in research, data on evidence-based strategies to increase enrollment of these populations are limited (UyBico et al., 2007).

Two prior reviews have highlighted what is known about recruitment and retention practices for pregnant and postpartum women involved in clinical research (Frew et al., 2014; van der Zande et al., 2018). Presently, there is a dearth of comprehensive recruitment and retention best practices for pregnant and early postpartum women engaged in long-term longitudinal cohort studies. The objectives of this scoping review were: (1) to synthesize the existing knowledge on recruitment and retention of pregnant women from diverse populations; and (2) to identify practical strategies that researchers can apply for effective recruitment and retention of these women and their children in birth cohort studies. Better understanding of the facilitators and barriers to recruitment and retention can help enhance the internal and external validity of future birth/pre-birth cohorts.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

A scoping review of three databases was electronically conducted to identify facilitators and barriers to recruitment and retention of pregnant women with variable risk in prospective birth cohort studies. Recruitment activities generally refer to identifying and approaching potential participants and consenting them to participate in the study. Retention is defined as the completion of follow-up visits and procedures as specified in a study protocol. We reviewed the existing literature, then analyzed the content of the abstracted data to identify emerging themes. This review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines (Tricco et al., 2018).

2.2. Search Strategy

Peer-reviewed publications in PubMed, Scopus, and CINAHL were searched from the inception of each database through April 28, 2020. A medical librarian was consulted on the search terms and strategy. A broad search of the literature was conducted to include studies that would accurately reflect a representative sample from the population. The search strategy cross-referenced the following Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms: perinatal care, pregnant women, postpartum period, patient participation, healthy volunteers, cohort studies, longitudinal studies, prospective studies. Examples of search strategies used are presented in Supplemental 1.

2.3. Study Selection and Eligibility Criteria

A researcher (EG) and medical librarian independently assessed titles and abstracts for relevance. Full text articles were independently reviewed and cross-checked for inclusion by study researchers with expertise in women’s health. Any disagreements in eligibility were discussed to reach a consensus among reviewers. Eligibility criteria included: (a) adults age ≥ 18 years, (b) pregnant women or the immediate to early postpartum period, (c) prospective, observational birth cohort studies, (d) written in English, and (e) published in peer-reviewed journals. Studies not compatible with an observational birth cohort design (e.g., clinical trials) and those reporting on primary outcomes without substantive information on recruitment strategies were excluded. Reporting on recruitment or retention outcomes was not a specifically stated inclusion criteria, since it would have substantially narrowed our eligibility criteria and consequently, the number of included articles. Studies were selected based upon detailed information provided on recruitment methodology and included some discussion on the utility of the various strategies utilized to enroll and engage pregnant women in research. Studies that contained sufficient recruitment information yet lacked retention details were also included.

2.4. Data Abstraction and Analysis

The following contextual data were collected: study design, study population, recruitment setting and methods, recruitment stage, eligible participants, enrollment number and rate, retention number and rate, and study duration. The abstracted data were entered and managed using Microsoft Excel. Data were initially abstracted into six subsections that comprised the coding framework and subsequent thematic analysis: (1) recruitment facilitators, (2) recruitment barriers, (3) retention facilitators, (4) retention barriers, (5) incentives, and (6) lessons learned, which were later described as study success factors. One researcher (SH) parsed the abstracted data into meaning units, defined as a word, phrase, sentence, or paragraph that represented a singular phenomenon, for further categorical analysis.

For the qualitative analysis, we assessed the placement of the meaning units in each of the subsections and indicated whether the unit of analysis was a facilitator or barrier. In the second level of analysis, a general inductive approach was used to create a coding scheme categorizing the abstracted meaning units from each subsection into themes, domains, and categories. To prevent bias in coding the data, intercoder reliability was established by calculating the percentage of agreement between coders. One researcher (KN) completed the first pass of coding, which was then reviewed by a second researcher (AT), followed by a group discussion (EG, KN, AT, SH) for consensus and discrepancy resolution. Intercoder reliability was established by calculating the percentage of agreement between coders that resulted in a total agreement of 97.5% (312/320 meaning units) between coders. Means and standard deviations were calculated in addition to reporting the rate of enrollment and retention across birth cohort studies that provided this information.

3. Results

3.1. Search and Selection

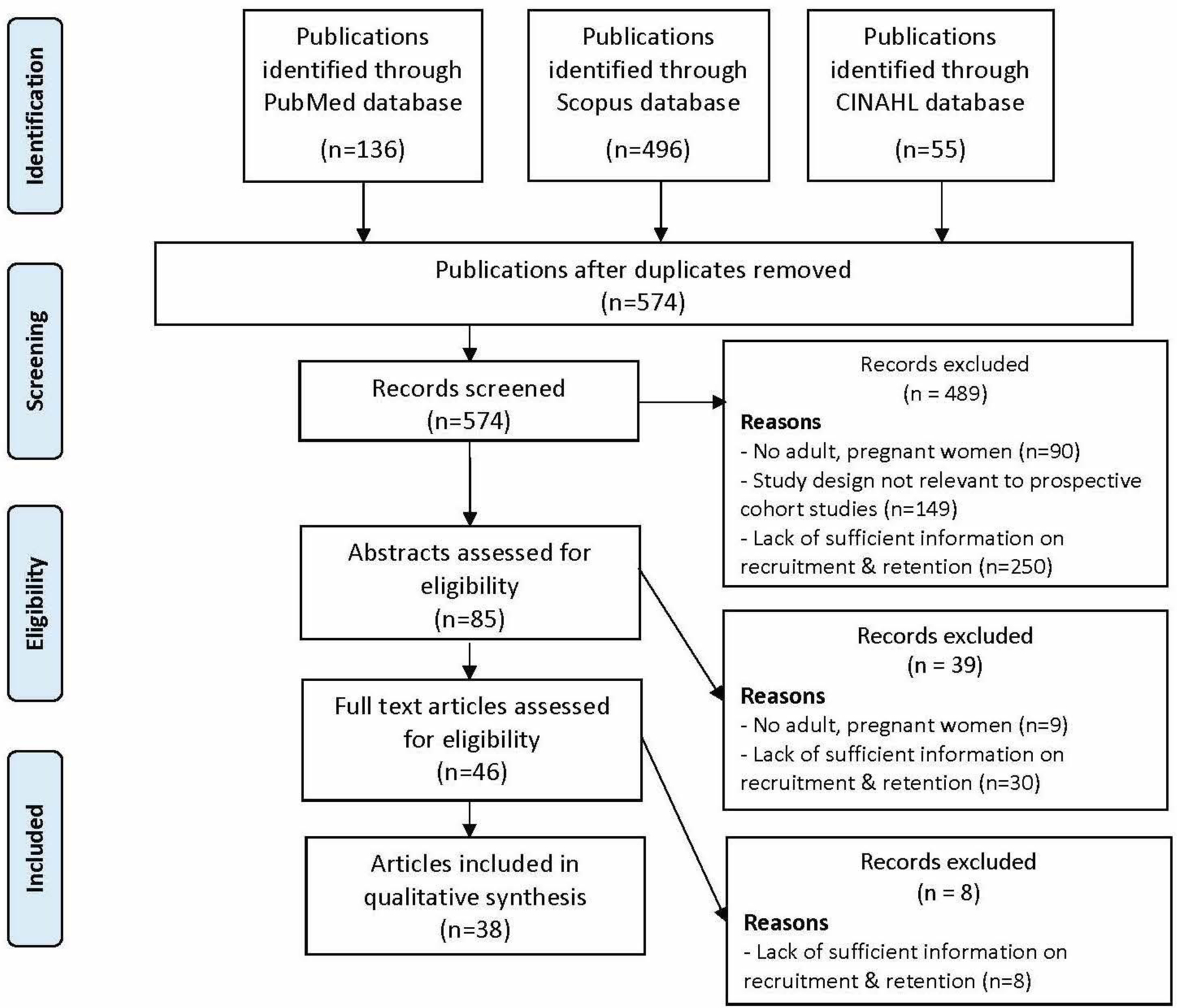

A literature search of PubMed, Scopus, and CINAHL databases resulted in 686 articles with 574 articles that were screened for eligibility after duplicates were removed. Altogether, 489 records were excluded due to lack of sufficient information on recruitment (n=288), study designs not relevant to birth cohort studies (n=149), or samples not including adult, pregnant women (n=99). Of the 47 studies that met the eligibility criteria, 38 articles were included in the synthesis and content analysis (see Fig. 1 Prisma Flowchart). The majority of meaning units (250, 79%) focused on recruitment practices and (68, 21%) on retention strategies. Overall, facilitators (241, 80%) were reported more often than barriers (77, 20%).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart

Note. Studies that lacked substantive detail about recruitment methodology, including elaboration on facilitators or barriers of engaging pregnant women in research were excluded.

3.2. Synthesis of Study Characteristics

Table 1 displays summary of findings that characterize the selected birth cohort studies. From the articles selected for inclusion in this scoping review (n=38), the majority were from birth cohort studies (n=20). Table 2 represents study designs (n=18), including 14 feasibility studies, 1 qualitative analysis of key informant interviews, 1 retrospective survey, and 2 monographs. Study sites described in the included articles were located in the United States (n=20) and international sites (n=19), including Canada (n=6), Australia (n=4), United Kingdom (n=3), and 1 each from Brazil, Netherlands, Lebanon, Oman, Italy, and China. Of the included studies, 6 publications represented pregnant women of diverse cultural backgrounds, including Hispanic (Chasan-Taber et al., 2009; Handler et al., 1997; Lara-Cinisomo et al., 2016; Phillips et al., 2011), South Asian (Neelotpol et al., 2016), African American (Handler et al., 1997), Pakistani (Raynor, 2008), and Lebanese, Syrian, and Palestinian (Ayoub et al., 2018) descent. Three studies recruited pregnant women of minority status impacted by socioeconomic disadvantage (Chasan-Taber et al., 2009; Phillips et al., 2011; Raynor, 2008).

Table 1.

Characteristics of prospective, observational birth cohort studies, including longitudinal studies (N = 20).

| Author / Date | Study Title | Study Population | Recruitment Setting/Methods | Recruitment Stage | Eligible (N) | Enrollment Rate N (%) | Retention Rate N (%) | Study Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chasan-Taber/2009 | Proyecto Buena Salud | Pregnant women of Caribbean Islander descent ages 16–40 | Obstetric practices during prenatal care visits | ≤20 weeks’ gestation | NA | 1,626 | 1,308 (80%) | 6 yrs |

| Dighe/2013 | Fetal Growth Longitudinal Study in US | Healthy pregnant women age <35 years and BMI <30 | Hospitals and medical centers | <14 weeks’ gestation | 13,108 | 4,607 (35%) | 3,976 (92%) | 5 yrs |

| Giuliani/2013 | Fetal Growth Longitudinal Study in Italy | Healthy pregnant women age <35 years and BMI <30 | Hospitals in eight recruitment settings that provide prenatal care services in Italy | <14 weeks’ gestation | 13,108 | 4,607 (35%) | 3,976 (92%) | 5 yrs |

| Jaffer/2013 | Fetal Growth Longitudinal Study in Oman | Healthy pregnant women age <35 years and BMI <30 | Hospitals in eight recruitment settings in Oman | <14 weeks’ gestation | 13,108 | 4,607 (35%) | 3,976 (92%) | 5 yrs |

| Leung/2013 | Alberta Pregnancy Outcomes and Nutrition Study (APrON) and All Our Babies (AOB) | APrON: Pregnant women age >16 years AOB: Pregnant, maternal age >18 years | APrON: community-based & face-to-face recruitment in maternity clinics; AOB: primary health care offices, & public health laboratory (Alberta, Canada) | APrON: <27 weeks’ pregnant AOB: <24 weeks’ pregnant | APrON: NA AOB: 4,011 | APrON: NA AOB: 3,300 (82%) | APrON: NA AOB: 2,969 (90%) | APrON: Ongoing AOB: 3 yrs |

| Manca/2013 | Alberta Pregnancy Outcomes and Nutrition (APrON) Study | Pregnant women age >16 years | High-volume maternity care, ultrasound clinics, and community-based outreach in Alberta, Canada | <27 weeks’ gestation | NA | NA | NA | Ongoing |

| Morton/2014 | Growing Up in New Zealand | Pregnant women from a defined geographic location in New Zealand | Direct engagement with prospective participants and community and indirect engagement via media in New Zealand | Unspecified gestational age | 10,315 | 6,822 (66%) | In progress | 21 yrs |

| Neelotpol/2016 | Mother and Baby’s Exposure to Lead Study | Pregnant women of South Asian or Caucasian origin | Government hospital and antenatal clinic in North England | Unspecified gestational age | 244 | 197 (81%) | 184 (93%) | 5 mos |

| Oken/2015 | Project Viva | Pregnant women | Prenatal care practices | <22 weeks’ gestation | 4,102 | 2,670 (64%) | 1,279 (48%) | 16 yrs |

| Promislow/2004 | Right From The Start Study | Women age 18–45 years trying to conceive for ≤6 mos and pregnant women | Private and prenatal care clinics, public clinics, community outreach | <12 weeks’ gestation | 963 | 803 (83%) | 781 (97%) | 1yr 9 mos |

| Qiu/2017 | Born in Guangzhou Cohort Study | Chinese pregnant women living in Guangzhou | Two birth centers in Guangzhou, China | <20 weeks’ gestation | 22,569 | 17,214 (76.3%) | 16,197 (94%) | 18 yrs |

| Raynor/2008 | Born in Bradford Cohort Study Fetal Growth | Low-income, multi-ethnic pregnant women | Bradford Royal Infirmary in UK | Between 26–28 weeks’ gestation | >80% | 12,452 (43%) | Ongoing through 2021 | 5 yrs |

| Roseman/2013 | Longitudinal Study in UK | Healthy pregnant women age <35 years and BMI <30 | University hospital in the United Kingdom | Between 5–12 weeks’ gestation | 13,108 | 4,607 (35%) | 3,976 (92%) | 5 yrs |

| Saiepour/2019 | Mater–University of Queensland Study | Pregnant women age 13–46 years | Hospital in Brisbane, Australia | Between 5–39 weeks’ gestation | 7,816 | 6,753 (87%) | 3,558 (53%) | 27 yrs |

| Savitz/1999 | Pregnancy, Infants, and Nutrition Study | Higher risk pregnant women age >16 years | Prenatal clinics at a teaching hospital and county health department | Between 24–29 weeks’ gestation | 1,843 | 1,051 (57%) | 956 (90%) | 2 yrs 4 mos |

| Silveira/2013 | Fetal Growth Longitudinal Study in Brazil | Healthy pregnant women age <35 years and BMI <30 | Obstetric hospitals in Pelotas, Brazil | <14 weeks’ gestation | 13,108 | 4,607 (35%) | 3,976 (92%) | 5 yrs |

| Thompson/2019 | Pregnancy and Influenza Project | Pregnant women following medical encounters for acute respiratory illness | Women were invited to join the study by telephone | Unspecified gestational age | 6,717 | 1,374 (20.4%) | 1,264 (92%) | 1 yr |

| Vuillermin/2015 | Barwon Infant Study | Pregnant women residing in the Barwon region of Australia | Public and private hospital in Australia | <28 weeks’ gestation | 1,158 | 1,074 (92.7%) | 894 (83%) | 4 yrs |

| Webster/2012 | Chemicals, Health and Pregnancy Study | Pregnant women with low-risk pregnancies | Community outreach in Vancouver, Canada | <15 weeks’ gestation | 349 | 171 (49.5%) | 152 (89%) | 1 yr 5 mos |

| White/2017 | Raine Study | Pregnant women | Tertiary obstetric hospital and private clinics in Western Australia | 16–20 weeks’ gestation | 3,535 | 2,900 (82%) | 636 (23%) | 26 yrs |

Note. Studies took place in the United States unless otherwise noted. Studies with a duration of ≥16 years were considered longitudinal. Abbreviations. NA = not applicable or unspecified; mos = months; yrs = years

Table 2.

Characteristics of feasibility and other studies (N = 18).

| Author / Date | Study Design | Study Population | Recruitment Setting/Methods | Recruitment Stage | Eligible (N) | Enrollment Rate N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ayoub/2018 | Qualitative focus groups and in-depth interviews | Pregnant women of Lebanese, Syrian, or Palestinian nationality | Pregnant women at public prenatal events & clinics and enrolled in a previous birth cohort study, and key informants (Lebanon) | Unspecified gestational age | NA | 44 |

| Baker/2014 | NCS Vanguard Study | Non-pregnant and pregnant women age 18 to 49 years | Community outreach and engagement | Unspecified gestational age | 2,286 | 1,399 (61%) |

| Bandstra/1992 | Monograph of longitudinal studies | Pregnant and postpartum women | NA | Unspecified gestational age | NA | NA |

| Blaisdell/2016 | NCS Vanguard Study | Non-pregnant and pregnant women age 18 to 49 years | Household canvassing and community outreach across 10 study locations | Unspecified gestational age | NA | 1,404 |

| Daniels/2006 | Retrospective survey | Women who participated in the most recent phase of the Pregnancy, Infants, and Nutrition study | Women who had indicated they were interested in further research during the study were mailed the follow-up survey. | 20 weeks’ gestation | 262 | 183 (70%) |

| Hale/2016 | NCS Vanguard Study | Non-pregnant and pregnant women age 18 to 49 years | Prenatal care provider (hospital or clinic) | Unspecified gestational age | 1,479 | 1,181 (80%) |

| Handler/1997 | Feasibility study of recruitment using Medicaid managed care lists | Pregnant African American and Latina women enrolled in Medicaid | Medicaid record abstraction | Unspecified gestational age | 1,009 | 348 (35%) |

| Kaar/2016 | NCS Vanguard Study | Non-pregnant and pregnant women age 18 to 49 years | Community-based recruitment (e.g., direct mailing, media, provider referral, social networking) | Unspecified gestational age | NA | NA |

| Lara-Cinisomo/2016 | Feasibility of recruiting Latina women in biomedical research | Perinatal immigrant and US-born Latinas | Outpatient prenatal visits in clinics & community centers | 3rd trimester | 65 | 34 (52%) |

| McGovern/2016 | NCS Vanguard Study | Non-pregnant and pregnant women age 18 to 49 years | Broad community outreach (e.g., study mailings) | Unspecified gestational age | 2,786 | 2,259 (81.1%) |

| Monk/2013 | Feasibility of booking midwife to recruit eligible women | Low-risk pregnant women | Midwifery units in hospitals in Australia | <28 weeks’ gestation | 436 | 146 (33%) |

| Phillips/2011 | Feasibility of recruiting Latina women | Mothers and full-term newborns | Hospital | Post-birth before hospital discharge | 422 | 255 (60%) |

| Richiardi/2007 | Feasibility of internet-based recruitment | Pregnant women | Posters and fliers at prenatal classes at Turin Hospital in Italy | Unspecified gestational age | 5,959 | 670 (10.1%) |

| Stanford/2015 | NCS Vanguard Study | Non-pregnant and pregnant women age 18 to 49 years | Household-based recruitment | <20 weeks’ gestation | 1,692 | 1,399 (61%) |

| Streissguth/1992 | Monograph of longitudinal studies | Pregnant and postpartum women | NA | Unspecified gestational age | NA | NA |

| Trasande/2011 | NCS Vanguard Study | Preconceptual and pregnant women age 18 to 49 years | Household-based recruitment | <27 weeks’ gestation | 4,889 | 2,811 (60.3%) |

| van Delft/2013 | Feasibility of recruitment of pregnant women | Pregnant women | University hospital in London, UK | 36 weeks’ gestation | 1,473 | 269 (18.3%) |

| van Gelder/ 2019 | Feasibility of recruitment using social media | Pregnant women | Clinicians and social media (Netherlands) | Between 8–12 weeks’ gestation | 456 | 392 (86%) |

Note. Study took place in the United States unless otherwise stated.

Abbreviations. NCS = National Children’s Study; NA = not applicable or unspecified

The birth cohort studies addressed a variety of pregnancy health conditions. Those represented included: spontaneous abortion (Promislow et al., 2004), gestational diabetes (Chasan-Taber et al., 2009), prenatal maternal nutrition related to mental health (Manca et al., 2013) and preterm delivery (Savitz et al., 1999), environmental (Vuillermin et al., 2015) and chemical exposure (Webster et al., 2012), and elevated lead levels (Neelotpol et al., 2016) exposure. Other studies examined issues of prenatal diet (Oken et al., 2015), influenza illness and vaccination (Thompson et al., 2019), selective loss to follow-up (Saiepour et al., 2019), and other factors related to maternal/child health and neurodevelopmental outcomes (Leung et al., 2013; Morton et al., 2014; Qiu et al., 2017; Raynor, 2008; White et al., 2017). The Intergrowth-21st Project, (n=5 publications), was a multi-ethnic, multi-center study dedicated to improving perinatal health.

Feasibility studies examined the barriers of recruiting Latina women (Lara-Cinisomo et al., 2016; Phillips et al., 2011), and the use of booking midwives (Monk et al., 2013), Medicaid managed care lists (Handler et al., 1997), social media (van Gelder et al., 2019), and other forms of internet-based recruitment as facilitators (Richiardi et al., 2007), as well as identifying specific factors that could influence recruitment (van Delft et al., 2013). The National Children’s Study (NCS) Vanguard Pilot Study, (n=7 publications), evaluated the feasibility and yield of a household-based sampling design to recruit pregnant and nonpregnant women in population-based research.

One study recruited women in the immediate postpartum period, but prior to discharge from the hospital (Phillips et al., 2011), whereas all other studies recruited women prenatally. Pregnant women were recruited between 5 and 39 weeks’ gestation, with 7 out of 20 birth cohort studies recruiting women during the first part of pregnancy (i.e., ≤ 20 gestational weeks). Studies utilized direct (e.g., face-to-face or telephone contact/email, household canvassing, community events), indirect (e.g., internet/social media, media advertisements, mailings, printed materials), and third party (e.g., word of mouth, provider and organization referrals) recruitment methods.

The average number of enrolled participants across birth cohort studies (n=14) was (4,172 +/− 5,067; range 171–17,214 participants). Several studies did not include retention outcomes as a result of being in progress with data collection. On average, 68% of participants were enrolled across 13 studies and 77.67% of participants were retained for the duration across 12 studies. The average study duration across birth cohort studies (n=14) was (9.44 +/− 9.94 years; range: 5 months – 26 years).

3.3. Incentives

Most studies reported incentives as an important motivator for participation. Free ultrasounds (Daniels, 2006, Dighe, 2013, Promislow 2004), providing bus passes (Webster et al., 2012) and gift cards to local businesses (Promislow 2004) were specifically discussed as recruitment incentives to encourage women to enroll in studies. While most publications did not delve into the impact that specific incentives provided, participants indicated that gaining information about their pregnancy through free ultrasound images was an important reason for choosing to participate in the study (Daniels, 2006).

Medical services were the most commonly cited retention incentive, including antenatal advice (Roseman et al., 2013), and nutrition counseling. Women were provided access to social support such as a “mom’s club” (Qiu et al., 2017). Transportation related retention incentives were also cited in multiple publications, e.g., free parking (Dighe et al., 2013; Oken et al., 2015; Roseman et al., 2013), travel reimbursement (van Delft et al., 2013), and bus passes to and from assessments (Webster et al., 2012). Additionally, incentives meant to help mothers meet the basic needs of her child and herself, such as diapers, meals, gift cards, and monetary compensation, were commonly used for completing assessments throughout the study. In some studies, access to food was offered in the form of meals or gift cards to grocery stores (Chasan-Taber et al., 2009; Phillips et al., 2011), while ultrasound images of the baby also improved retention. (Dighe et al., 2013; Giuliani et al., 2013; Roseman et al., 2013; Silveira et al., 2013). A few studies further explained the impact of provided incentives on participant retention. For example, the INTERGROWTH-21 study, which provided participants with highly personalized antenatal advice and ultrasound images of the child, stated that women were less likely to drop out of the study as a result (Roseman, 2013). A few studies cited baby apparel with and without the study logo as an incentive, but did not specify whether this was specifically aimed to improved study recruitment or retention (Chasan-Taber et al., 2009; Webster et al., 2012).

3.4. Recruitment Qualitative Themes

The results of this scoping review highlight facilitators and barriers of recruiting pregnant women in birth cohort studies (Table 3). All of the selected studies reported on recruitment methods, which totaled 253 meaning units. The majority of abstracted data (79%) focused on recruitment practices. Recruitment facilitators (n = 184) were reported more often than barriers (n = 69). The predominant recruitment themes included: role of clinics, direct, indirect, and third-party recruitment; contacting participants; participant factors; and cultural considerations.

Table 3.

Content analysis of recruitment facilitators (N = 184) and barriers (N = 69) from the included studies

| Theme | Domain | Category |

|---|---|---|

| Who (n = 28) | Recruitment Facilitators (n = 28) | |

| Medical provider (n=11) | “Champion” midwives, nurses, primary care provider, gynecologist | |

| Research study staff (n=8) | Research assistant, trained recruiter/interviewer | |

| Clinic staff (n=7) | Clinical staff, local ‘onsite’ staff, e.g., receptionist, office manager, nursing personnel | |

| Other (n=1) | Contract agency | |

| Recruitment Barriers (n = 1) | ||

| Medical provider (n=1) | Direct contact via physicians and midwives was relatively expensive and unsuccessful. | |

| Where (n = 48) | Recruitment Facilitators (n = 39) | |

| Clinic/hospital (n=30) | Prenatal visit/exam (n=11), on-site (unspecified; n=8), waiting room (n=5), routine blood collection/tests (n=2), hospital tour, satellite clinic, physician offices | |

| Community (n=6) | Public prenatal events, community classes, e.g., birthing, parenting and breastfeeding | |

| Prior studies (n=2) | Phone numbers on file, subset of existing longitudinal study | |

| Home (n=1) | Household-based recruitment | |

| Recruitment Barriers (n = 9) | ||

| Clinic (n=8) | Unregistered pregnant women, missed/cancelled/rescheduled visit, prenatal care bias, medical exam took priority, recruiters busy with other participants, clinical demands and priorities, lack of engagement | |

| Gated community (n=1) | Restricted access | |

| Direct Recruitment (n = 21) | Recruitment Facilitators (n = 21) | |

| Postal mail (n=9) | Targeted outreach by mail, multiple mailings, study leaflets included with screening results, personalized letters | |

| In-person (n=6) | Personal recruitment positively influenced initial enrollment, e.g., offering leaflets by research staff, gynecologists during medical exams, and in prenatal classes, community classes, clinics, hospital wards, and shops. | |

| Clinic (n=2) | Electronic health records, patient addresses and clinical schedules | |

| Door-to-door (n=2) | Targeted households | |

| Phone (n=2) | Phone response was higher when local staff made invitation calls. | |

| Indirect Recruitment (n = 31) | Recruitment Facilitators (n = 26) | |

| Posters/pamphlets (n=7) | Pharmacy, community, physician offices, clinics, hospitals, bookstores, childcare facilities, coffee shops, gym, in-person, etc | |

| Media (n=8) | TV, radio, newspapers, local news story, press releases, advocacy campaign | |

| Internet (n=4) | Facebook, Google AdWords, study website, articles on university websites | |

| Internet/social media (n=2) | Facebook, Google AdWords | |

| Paid advertising (n=3) | Billboards, advertising campaigns, internet, print advertising | |

| Branding (n=2) | Recognizable study brand, e.g., study logo, study website, baby T-shirts, refrigerator magnets, | |

| Recruitment Barriers (n = 5) | ||

| Internet/social media (n=2) | Social media bias, e.g., inequitable recruitment, costly w/o high return | |

| Awareness (n=2) | Poor public awareness of research, better advertising could lead to higher response rates | |

| Newspaper (n=1) | No detailed study information, time limited, e.g., only runs for one day | |

| Third-Party Recruitment (n = 23) | Recruitment Facilitators (n = 21) | |

| Outreach (n = 13) | Community outreach activities, e.g., press conferences, presentations, community events (e.g., information booths at “baby” trade shows and pregnancy fairs), leaflets at birth classes, charitable events; networking with pregnancy community; engagement of local stakeholders; links with community organizations; gaining trust and permission of “gatekeepers” such as apartment managers or homeowners’ boards, public health officials; prominent members of clinical community; public relations activities between research team and clinicians and community leaders; introduce study to hospital teams and encourage them to refer eligible women | |

| Partnerships (n = 5) | Advocacy campaigns with organizations, collaboration with ‘Moeders voor Moeders’ (Mothers for Mothers), community organizations, Department of Health and Human Services, Medicaid Managed Care Agency | |

| Word of mouth (n=3) | Study participants, friends, colleagues | |

| Recruitment Barriers (n = 2) | ||

| Partnership (n=1) | Time-consuming for researchers to establish those relationships | |

| Outreach (n=1) | Difficult to ascertain which strategies were most effective given idiosyncratic nature of community-based outreach. | |

| Contacting Participants (n = 14) | Recruitment Facilitators (n = 8) | |

| Phone (n=4) | Contacted within one week of visit, up to 10 contact times on different days at different times, contact women who did not initially consent or decline | |

| Internet (n=2) | Participants can contact study team via web-based Facebook page. Study team can use email to follow-up and make procedures more efficient with participants. | |

| Text (n=1) | No fee for texting | |

| Multiple contacts (n=1) | Provide home, cell, and work telephone numbers and the name and telephone number of one relative or friend who did not live with them. | |

| Recruitment Barriers (n = 6) | ||

| Internet (n=5) | Selection bias due to self-selection and/or access, lack of access, inability or problems with using the internet, lack of physical contact with participants, (e.g., collection of biological specimens), issues of privacy | |

| Staff (n=1) | Not having adequate staff coverage to contact as high proportion of eligible women as possible | |

| Participant Factors (n = 58) | Recruitment Facilitators (n = 22) | |

| Motivators (n=16) | Helping others, helping oneself, contributing to science/research, prior participation in research, convenience, staying within one’s comfort zone, physician’s endorsement, personal relevance to the topic, high regard for academic universities/hospitals, incentives and participation, early in pregnancy, “give back” | |

| Considerations (n=6) | Work-life balance, ethics, reputation of research institution, interpersonal skills of researcher, trust in research team/institution, accessibility | |

| Recruitment Barriers (n = 36) | ||

| Reasons for refusal (n=25) | Bio-intensive protocol, participant burden, unwilling to consent, concerns of confidentiality, religious beliefs, stress in pregnancy, not interested, no permission from mother or husband, invasive, sensitive topics, child development assessments, problems using internet | |

| Other barriers (n=11) | Transportation, less certain about allowing their children to participate in future research, more educated women appeared more cautious regarding collection of biospecimen data, lack of familiarity with research, misconceptions about research, influenza epidemic, distrust of study team, unmet basic needs, preoccupied with needs of the baby, inconvenience, type of data collected | |

| Cultural Considerations (n = 29) | Recruitment Facilitators (n = 19) | |

| Multilingual staff (n=7) | Interpreters, bilingual recruiters and interviewers, team fluency in key community languages, bilingual research staff in clinical offices, interviewer-administered questionnaire | |

| Multilingual materials (n=6) | Translating recruitment materials, study documents, data collection instruments | |

| Low-income, minority women (n=3) | Diverse community engagement strategies, personal recruitment techniques, e.g., face-to-face, financial incentives | |

| Cultural sensitivity (n=2) | Sensitive to culturally specific practices, cultural norms, and religious practices; adapting research design and implementation strategies to minimize cultural differences, matching recruiters by race/ethnicity | |

| Trust (n=1) | “Development of trust and confidence between the participant and the researcher is the key to the success of a clinical and epidemiological study involving ethnic minorities (Neelotpol, 2016).” | |

| Recruitment Barriers (n = 10) | ||

| Lack of trust (n=4) | Immigrant communities, reserved about research, conservativeness, e.g., not able to get permission from other family members to participate, mistrust of government and health providers | |

| Language (n=3) | No bilingual research staff, translation/interpreter costs | |

| Cultural sensitivity (n=3) | Perceived stereotypes sustaining cultural myths held by researchers; failure of recruiters to acknowledge important values, discrepant views between potential participants and researchers | |

3.4.1. Role of clinics

On-site screening for eligibility and administration of consent at the prenatal care clinics, hospitals or maternity centers was identified as one of the most successful recruitment strategies (Hale et al., 2016; Leung et al., 2013; Promislow et al., 2004; van Delft et al., 2013; Webster et al., 2012). Pregnant women were often approached by a research assistant in the waiting room before their scheduled prenatal care appointment (Chasan-Taber et al., 2009; Morton et al., 2014; Oken et al., 2015). Involvement of bilingual research assistants was beneficial in some studies (Chasan-Taber et al., 2009) as well as a general introduction of the study by healthcare providers before a patient was approached by a research team member (Ayoub et al., 2018). In addition, direct recruitment by healthcare providers (e.g., physician or a midwife) was identified as a valuable strategy (Hale et al., 2016; Richiardi et al., 2007; van Gelder et al., 2019) and was found to be a more efficient approach than online recruitment via social media (Raynor, 2008; Trasande et al., 2011; Wright et al., 2013). Some studies identified designated liaisons among clinical personnel (e.g. ‘midwifery champions’) who coordinated recruitment activities with the research staff and helped to pre-screen potentially eligible subjects (Monk et al., 2013). Other facilitators included shortened interview time (Chasan-Taber et al., 2009) and reminders to the clinical personnel to invite patients to participate (Monk et al., 2013).

Some studies identified last minute cancellations or rescheduled appointments and staffing constraints as major barriers for on-site recruitment (Chasan-Taber et al., 2009; Savitz et al., 1999). In these situations, selection bias could potentially be introduced if women did not have regular prenatal care or initiated visits late in gestation, since those patients would be less likely to be approached and recruited (Bandstra, 1992). This would be particularly pertinent to women with substance use disorders and those with limited or intermittent access to healthcare due to a variety of factors, e.g., living in rural and/or medically underserved areas, limited transportation, migrant populations, patients with unstable housing and other social vulnerabilities. Additionally, exclusion of non-English speakers and recruitment from public hospitals might introduce selection bias (Ayoub et al., 2018). Healthcare disparities could make it harder to recruit hard-to-reach populations from prenatal clinics and to obtain a representative sample. To offset such challenges, multiple healthcare recruitment sites were cited as necessary to recruit a diverse study population (Savitz et al., 1999). To minimize or at least characterize the extent of selection bias, it was identified as important to compare characteristics of those women who were approached but did not agree to participate and those who ultimately enrolled (Saiepour et al., 2019). However, this strategy was noted to be logistically challenging for clinics to keep track of the characteristics of nonparticipants.

Other barriers identified included resources and time needed to engage healthcare providers (Blaisdell et al., 2016), develop a customized approach for study procedures in each practice, conduct comprehensive outreach with midwifes across all clinical units involved (Neelotpol et al., 2016), and address attrition of prenatal care providers from recruitment efforts over time due to demands of their clinical loads (Neelotpol et al., 2016; van Gelder et al., 2019). Often screening criteria and research protocols were found to be too complex for regular clinic staff to accommodate when serving as part-time recruiters, while engagement of clinical personnel to screen and recruit participants increased research costs (Manca et al., 2013; Savitz et al., 1999).

3.4.2. Direct recruitment strategies

Direct recruitment differs from “marketing” as it is targeted toward pre-specified individuals or groups and extends beyond raising awareness on the part of the viewer toward intentionally building a relationship with the person being contacted. While a variety of methods were employed to enlist pregnant women for research studies, direct recruitment was proven to be a universally successful strategy, especially when it involved engagement with other members in the community and professionals in health care settings (Daniels et al., 2006; Manca et al., 2013; Monk et al., 2013; Morton et al., 2014; Richiardi et al., 2007). It was found to be helpful to obtain participants’ contact information during the initial interaction so that a follow-up phone call could be made to answer additional questions and enroll subjects (Morton et al., 2014). Similarly, Manca et al. (2013) found the most effective recruitment strategy in large volume clinic settings was face-to-face interactions with physicians at clinics and ultrasound offices. Other effective direct recruitment strategies in the community included posting brochures in pharmacies and targeted mailings to new homeowners (Promislow et al., 2004).

Pregnant women from vulnerable or hard-to-reach subgroups, especially those from ethnic minorities have historically been difficult to recruit into research (Promislow et al., 2004). Although often associated with later enrollment, direct recruitment at public prenatal clinics was considered essential to increase study representation of minorities, lower income women, and women with at-risk health behaviors (Promislow et al., 2004). In addition, a “direct approach” and one-to-one engagement with participants by a researcher of a similar background, including having a shared language, cultural awareness, and appreciation was noted to be vital. The key to successful participation was described as the development of trust and confidence between the participant and the researcher, especially in populations involving ethnic minorities (Neelotpol et al., 2016). When minorities are largely located in an urban setting, directly approaching households by going door-to-door to identify eligible women has been found to have a similar success rate as that in the inpatient hospital setting, where a clinical relationship precedes study participation (Trasande et al., 2011). In contrast, when targeting eligible women in smaller, less densely populated areas, a direct outreach marketing approach through unique direct mailings with incentives and community activities was found to be effective in gaining the trust of community members (Kaar et al., 2016).

3.4.3. Indirect recruitment strategies

A number of diverse methods were employed by investigators to connect the study with the broader community. Online advertising as well as the use of posters and flyers were found to generate many inquiries, but were less cost effective due to the high cost of printing and the staff time required to curate a list of appropriate websites and advertising venues (Webster et al., 2012). Although study booths were an exceptionally time-intensive recruitment method, they allowed women to directly interact with the study staff. Additionally, some studies reported that having a recognizable study brand, such as a logo displayed on flyers, posters, magnets, and the study website, was advantageous (Blaisdell et al., 2016; Webster et al., 2012). Social media was considered a popular method to heighten public awareness, specifically platforms such as Google AdWords, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Instagram, and LinkedIn (van Gelder et al., 2019).

One of the largest barriers for research participation was poor public awareness of research among different segments of the population. Although Facebook Ads could reduce recruitment costs and time and increase recruitment numbers, this approach has been largely criticized for its potential to bias recruitment towards women that are younger, more facile with technology, and have a higher level of education (Ayoub et al., 2018; van Gelder et al., 2019). Contrary to the success of mainstream and social media, media coverage using newspapers and press releases were found to yield some of the lowest number of inquiries given the limited duration of exposure through media channels (Webster et al., 2012). Other unsuccessful marketing strategies included the use of stamped study postcards designed to collect participant contact information in the community and flyer distribution at large health trade shows without an accompanying booth or on-site staff presence (Webster et al., 2012).

3.4.4. Third-party recruitment strategies

Studies leveraged community sites that catered to the needs of pregnant women to conduct outreach by raising awareness and to form partnerships for enhancing engagement with potential participants in these settings. Community-based recruitment sites varied greatly by the target population, and often included public prenatal events (Ayoub et al., 2018), antenatal health education classes (Neelotpol et al., 2016; Richiardi et al., 2007), parenting and breast-feeding classes (Morton et al., 2014), community events including charitable events (Baker et al., 2014; Kaar et al., 2016), and pregnancy fairs (van Gelder et al., 2019). Health educators and peer support groups were identified as important partners (Jaffer et al., 2013) as well as community organizations (Raynor, 2008) and other local stakeholders (Blaisdell et al., 2016). The most cost-effective recruitment methods were word of mouth, including forwarded recruitment emails and other study materials passed on by friends and research-related listservs (Webster et al., 2012). The most efficient recruitment methods, however, were dependent on the goals of the study and patient population (Blaisdell et al., 2016).

3.3.6. Contacting participants

Several methods of communication between research team members and potential participants were identified as effective for recruitment. Specifically, calling or emailing participants to conduct their interview (Ayoub et al., 2018; Savitz et al., 1999; Webster et al., 2012), and making additional attempts to contact participants on varying days and times as well as contacting women that did not initially consent or decline were important (Webster et al., 2012). Some studies employed flexible recruitment strategies to enhance participation by obtaining multiple forms of contact in anticipation of potential interruptions during the initial baseline interview (Chasan-Taber et al., 2009). The communication skills of recruiters influenced recruitment success, including their ability to provide study information, obtain informed consent, and discuss uncertainty with potential participants such as allowing their child to participate in future research (Baker et al., 2014; Daniels et al., 2006).

Prior studies have also identified a variety of communication obstacles that lead women to decline participation. Of these challenges, language was identified as a prominent barrier that could influence participation, especially from minority groups (Brown et al., 1997; Manca et al., 2013). Another limiting factor was the difficulty for recruiters to capture and talk to each eligible patient due to staffing constraints or competing priorities with medical care (Chasan-Taber et al., 2009; Savitz et al., 1999). Additionally, studies that did not use the internet for recruitment were found to be at a disadvantage, in part because of the inability to use email as a tool to improve efficiency and coordinate follow up (Richiardi et al., 2007).

3.4.5. Participant factors

Participant factors are the conditions that influence the decision of a potential participant to join the study. General altruism, contribution to science, and the desire “to give back” to society were identified as common motivators (Daniels et al., 2006; Lara-Cinisomo et al., 2016; Savitz et al., 1999). Similarly, women’s interests in learning more about their own pregnancy, personal relevance of the research topic, and anticipated benefits were noted to facilitate participation (Ayoub et al., 2018; Daniels et al., 2006). Some studies indicated that previous research participation, physician’s endorsement, reputation of the hospital/academic center, basic underlying trust in both the research team and the research institution, and convenience also appeared to be important motivators (Ayoub et al., 2018). Additionally, specific patient characteristics, such as being early in gestation (Qiu et al., 2017), presence of co-morbidities (Thompson et al., 2019), high self-confidence and self-efficacy (Daniels et al., 2006), served as facilitators. Highlighting the successful stories from previous studies (Ayoub et al., 2018) and providing a clear explanation of the study goals, the commitment required for participation, and potential benefits (van Delft et al., 2013) were identified as approaches to minimize barriers. Participant considerations, such as balancing study participation with family and work-related activities, interpersonal skills of the researchers, and basic trust in the research team and institution, further shape decisions to enroll in a study (Ayoub et al., 2018). Allowing for participants to openly share their concerns facilitates trust and confidence in the research process leading to increased recruitment (Daniels et al., 2006).

In terms of barriers, the major contributors that could affect participant engagement were concerns about a potential breach of confidentiality, fear of legal retribution (Bandstra, 1992; Monk et al., 2013; Richiardi et al., 2007), high participation burden, and time constraints (Ayoub et al., 2018; Manca et al., 2013; Vuillermin et al., 2015). Several studies reported concerns about biospecimen collection (Ayoub et al., 2018; Manca et al., 2013; Webster et al., 2012), such as the bio-intensive nature of the protocol (Vuillermin et al., 2015). A particular concern in studies was any physical or biological data collection required from offspring (Daniels et al., 2006), especially in the neonatal period (Neelotpol et al., 2016). Other barriers included lack of transportation (Lara-Cinisomo et al., 2016), unmet basic family needs (Bandstra, 1992), lack of internet access (Richiardi et al., 2007), preoccupation with needs of a newborn infant, religious beliefs, and lack of permission for participation from other family members (Neelotpol et al., 2016). Financial constraints and the cost of outreach efforts also posed a challenge to many studies. Economic hurdles also included the constraints on the financial incentives that recruiters could offer participants (Brown et al., 1997).

3.4.6. Cultural considerations

Cultural considerations are those that can help or hinder studies to adapt to specific cultural contexts. The use of multilingual staff, availability of multilingual materials, and cultural competence were major facilitators in the recruitment of participants who were non-proficient/non-English speakers (Chasan-Taber et al., 2009; Jaffer et al., 2013; Lara-Cinisomo et al., 2016; Raynor, 2008; Silveira et al., 2013; Wright et al., 2013). It was highly beneficial for participants to be approached by someone from the same cultural/ethnic background who could understand and appreciate their language and culture (Silveira et al., 2013). Previous studies demonstrated that researcher sensitivity to cultural norms and practices was extremely important for securing the confidence of participants and establishing trust (Neelotpol et al., 2016). While language-specific materials were considered important, some studies have noted that translation of materials into a different language was time consuming and costly (Phillips et al., 2011). Other barriers included the lack of trust by members of minority and immigrant communities (Richiardi et al., 2007), concerns over residency status (Handler et al., 1997), cultural stereotypes (Neelotpol et al., 2016), and the need for approval from other family members (Ayoub et al., 2018).

4.1. Retention Qualitative Themes

The results of this scoping review also highlight facilitators and barriers of retaining pregnant women in birth cohort studies (Table 4). Of the 38 included studies, 27 studies explored retention strategies, which totaled 67 meaning units. There were far fewer descriptions of retention than recruitment throughout the included studies, with only 21% of the total meaning units addressing retention strategies. Retention facilitators (n = 57) were reported more often than barriers (n = 10). The predominant retention themes included: reducing participant burden, contacting and tracking participants, and patterns in retention and attrition.

Table 4.

Content analysis of retention facilitators (N = 57) and barriers (N = 10) from the included studies

| Theme | Domain | Category |

|---|---|---|

| Setting (n = 11) | Retention Facilitators (n = 11) | |

| Home visit (n=4) | In-person visits offered to those unable to travel | |

| Clinic/hospital visit (n=4) | Research clinic, study hospital | |

| Home assessment (n=3) | Web-based questionnaires, study kits, questionnaires by post | |

| Retention Barriers (n=1) | ||

| Clinic/hospital; (n=1) | Liaison with the hospital staff and fitting in with the daily hospital routines were essential, but not always easy to achieve. | |

| Scheduling (n = 6) | Retention Facilitators (n = 6) | |

| Flexibility (n=4) | Adaptable to needs of cohort, option to reschedule, choice of in-person or phone, not discouraged to bring relatives or children to appointments | |

| Convenience (n=2) | Coordinated visits with scheduled appointments | |

| Contacting participants (n = 27) | Retention Facilitators (n = 25) | |

| Tracking (n=5) | Frequent family contact, (e.g., holiday greeting cards with address correction requested, handwritten envelopes, attractive postage), electronic health records; computerized tracking system, database linkage techniques | |

| Multiple personal contacts (n=4) | Contact details of up to four relatives or friends, current partner, 2 non-household contacts | |

| Phone (n=3) | 24-hour answering machine, remind/schedule/confirm appointment one week in advance, remind 1-day in advance | |

| Postal mail (n=3) | ‘Thank you’ letters, confirmation of upcoming appointments | |

| Text (n=3) | Automated texting as appointment reminders | |

| Email (n=3) | Follow-up and appointment reminder | |

| Frequency (n=2) | Maintaining regular contact every 6–12 months | |

| Other (n=2) | Appointment cards, personalized messages | |

| Retention Barriers (n = 2) | ||

| Phones (n=1) | Inability to contact participants were more common in women with lower education and 3 or more children compared to one birth | |

| Text (n=1) | Not having use of texts were a missed opportunity | |

| Participant Factors (n = 12) | Retention Facilitators (n = 7) | |

| Motivators (n=7) | Fostering healthy habits, ideal number of appointments, informed of importance of study, regular updates, continued positive experiences, comfortable completing study activities, positive attitude and enthusiasm about study | |

| Retention Barriers (n = 5) | ||

| Barriers (n=5) | Loss of interest, pregnancy loss, relocation, multiple caregiver shifts, substance abuse/psychiatric problems | |

| Cultural Considerations (n = 10) | Retention Facilitators (n = 8) | |

| Cultural sensitivity (n=4) | Culturally relevant strategies, e.g., translation services, study materials, and text and phone messages received and answered in participant’s preferred language | |

| Flexibility (n=2) | Alignment of study processes with cultural and community needs, Omani women travel in the summer to cooler climates | |

| Trust (n=2) | Providing early data feedback and results regardless of length of participation, accessibility to principal investigator | |

| Retention Barriers (n = 2) | ||

| Loss of contact (n=2) | Changes of address; changes of phone numbers | |

4.1.1. Reducing participant burden

Overall, reducing participant burden was considered a major factor in retention (Ayoub et al., 2018). The location where study data was collected and the associated ease of continued participation were foremost considerations. Several studies found that offering home visits as an alternative was important in retention (Oken et al., 2015) and some participants actually preferred them (Wright et al., 2013). Follow-up home visits in combination with clinic visits were also found to be helpful for tracking and maintaining relationships with the participants (Baker et al., 2014). As an alternative to in-person clinic or home visits, some studies found mailed or web-based questionnaires were reasonable alternatives (Manca et al., 2013; Saiepour et al., 2019); however, response rates to questionnaires without an accompanying in-person visit could be low (Leung et al., 2013). In particular, mailed questionnaire responses and completion rates were found to be potentially lower than web-based versions (Richiardi et al., 2007).

Flexibility was considered essential by several studies, including the timing of scheduled study visits in the clinic, at home, or by telephone; sensitivity to holidays and vacation schedules; and high tolerance for requests to reschedule a visit (Jaffer et al., 2013; Lara-Cinisomo et al., 2016; Walker et al., 2011). Coordination of study data collection visits with other routine health care events, such as primary care, gynecological, or pediatric appointments, was also considered a facilitator (Roseman et al., 2013). Utilizing electronic health records provided a means for cost-effective follow-up with participants on a variety of health outcomes and was noted to be an important contributor to retention by limiting the burden of participant contacts (Wright et al., 2013).

4.1.2. Contacting and tracking participants

Similar to communication for initial recruitment, many studies described the importance of robust communication strategies to optimize retention. Traditional mail, email, text, social media, and phone calls were described as facilitators of retention. Mailings were best used to send ‘thank you’ letters and upcoming appointment reminders (Dighe et al., 2013; Lara-Cinisomo et al., 2016). Email and text messages were strongly advised for appointment reminders and maintaining contact (Baker et al., 2014; Dighe et al., 2013; Jaffer et al., 2013; Qiu et al., 2017; Richiardi et al., 2007; Roseman et al., 2013). White et al. (2017) found engaging study participants on social media promoted retention. Telephone reminders were associated with continued study participation. Some studies included reminder calls the day prior (Dighe et al., 2013) or one week prior to a study visit (Silveira et al., 2013). Others reported that contact with participants every 6–12 months by phone also aided in retention (Lara-Cinisomo et al., 2016; Morton et al., 2014). A 24-hour telephone answering service that was checked 3–4 times during the workday was highlighted as an important communication tool (Roseman et al., 2013). Similar to personalized mailings, personalized messages have been shown to improve retention (Bandstra, 1992; Daniels et al., 2006). Moreover, retention was also improved by emphasizing the importance of follow-up at each encounter (Dighe et al., 2013). Baker et al. (2014) noted that unclear guidance regarding the duration and importance of follow-up was a limitation of their study, which may have led to high attrition.

Protocols and tracking systems for maintaining study participant contact information were necessary to retain their involvement. Having multiple means of contacting study participants has been found to promote retention (Bandstra, 1992; Morton et al., 2014; Saiepour et al., 2019; Webster et al., 2012). Some authors recommended requesting contact information for a partner (Morton et al., 2014), up to 4 relatives or friends (Saiepour et al., 2019), or 2 non-household contacts (Webster et al., 2012), to increase the likelihood of remaining in contact with study participants. Saiepour et al. (2019) emphasized the importance of updating all of the contact information for a participant at each encounter. Four studies advised using electronic tracking systems (Bandstra, 1992; Morton et al., 2014; Phillips et al., 2011; Savitz et al., 1999) to locate participants. Bandstra (1992) recommended using database linkages to successfully track research participants. In one study, half of participants were lost to follow up due to invalid phone numbers or having moved (Baker et al., 2014). Thompson et al. (2019) noted that failing to use text reminders may have reduced retention. Inability to maintain contact with mothers was greater among impoverished women, those with lower education, and those with 3 or more children (Savitz et al., 1999).

4.1.3. Patterns in retention and attrition

Motivators that were cited for individual participants staying in the study included enjoyment of the study benefits in improved health, importance of the study on the larger scale of the community or population, and being kept informed on study progress and findings (Giuliani et al., 2013; Roseman et al., 2013). In addition, retention was influenced by the participant’s perception of a positive experience with the study team, an acceptable level of burden, and comfort with the study procedures and activities (Daniels et al., 2006; Morton et al., 2014). Participants who were impressed by study staff on the individual importance of their data were more motivated to complete study visits (Dighe et al., 2013). Assurances of confidentiality and with whom data would be shared were important for retention in some studies (Lara-Cinisomo et al., 2016), as well as the perceived anonymity of providing data via the internet.

Conversely, social or cultural factors such as disrupted family life, unstable housing, frequent relocation, substance use and loss of interest were barriers to retention (Baker et al., 2014; Bandstra, 1992; Phillips et al., 2011; van Delft et al., 2013; Webster et al., 2012). With respect to factors associated with both attrition and incomplete data capture, many studies variably noted attrition was more common in women who were low-income, less educated, younger, multiparous, and had disadvantaged social backgrounds, unstable marital partnerships, mental illness, substance use, unplanned pregnancies, and in some cases among ethnic minority groups (Manca et al., 2013; Qiu et al., 2017; Richiardi et al., 2007; Saiepour et al., 2019; Savitz et al., 1999; Vuillermin et al., 2015). While there was a high number of losses to follow-up in the first 1–5 years after enrollment noted in some studies, smaller incremental attrition in subsequent years of the study was noted to be cumulatively impactful (Baker et al., 2014).

An important consideration was the overall high cost of maintaining study participants over time. This was successfully addressed by some through developing research partnerships to pool financial resources devoted to retention activities (Oken et al., 2015). Other strategies included incorporating electronic health records as a low-cost source of data capture over time (Wright et al., 2013). However, some studies emphasized the importance of addressing high costs of retention, especially with biospecimen collection and the risk of instability in funding sources to support retention (Neelotpol et al., 2016; Wright et al., 2013). Of key importance, differential attrition rates in specific subgroups over the course of a longitudinal study were noted as a threat to internal validity (Wright et al., 2013).

5.1. Study success factors

In this section, we have highlighted some of the decisions that impact the entire study, including hiring and training decisions that are focused on building trusting relationships with participants. Successful teams were often multidisciplinary, and many included medical professionals (e.g., physicians, nurses, midwives, anthropometrists), social workers or case workers, and researchers (i.e., bilingual coordinators, research coordinators, interviewers) (Bandstra, 1992; Dighe et al., 2013; Giuliani et al., 2013; Jaffer et al., 2013; Roseman et al., 2013; Silveira et al., 2013; Wright et al., 2013). Team members were trained in building strong and trusting bonds with study participants (Dighe et al., 2013). Some studies suggested specific attitudes for team members, such as being non-judgmental, friendly, kind, understanding and professional (Ayoub et al., 2018; Bandstra, 1992; Daniels et al., 2006; Neelotpol et al., 2016; Qiu et al., 2017; van Delft et al., 2013). One study suggested that staff should be warm, empathetic and enthusiastic individuals with whom participants could identify (Webster et al., 2012). Relationship-building practices such as sending cards and letters (Bandstra, 1992; Leung et al., 2013; Webster et al., 2012), texting or using social media (Leung et al., 2013; Neelotpol et al., 2016), and organizing social events such as monthly cohort parties (Bandstra, 1992; Leung et al., 2013; Qiu et al., 2017) were found to be beneficial. A number of studies that emphasized relationship-building with participants reported enhanced trust and comfort with research staff and medical professionals (Daniels et al., 2006), alleviated fears of participating in research (Giuliani et al., 2013), and increased retention rates (Neelotpol et al., 2016).

3. Discussion

The purpose of this scoping review was to map the literature by comprehensively identifying and analyzing the existing knowledge on recruitment and retention of pregnant women in birth cohort studies. As a result, we were able to present a large and diverse body of literature that identified key concepts as well as gaps in the research, such as longitudinal studies reporting on retention practices that engage pregnant women in research beyond their pregnancy. Recruitment and retention efforts can be costly and labor-intensive, yet worthwhile in obtaining the long-term commitment of study participants and critically important in achieving sustainability and study success. Findings from the present analysis point to the centrality of building trusting relationships, limiting participant burden, and employing culturally relevant strategies as principal tenets of study success. Proactively addressing participant and cultural factors; in addition to demonstrating responsivity and willingness to troubleshoot concerns as they arise can help to lessen the challenges of recruitment and retention for this population.

Concordant with prior reviews (Frew et al., 2014; van der Zande et al., 2018), results from this review indicate that key recruitment facilitators include fostering relationships, implementing diverse recruitment methods, and providing cultural-specific materials. In contrast, participant factors (e.g., invasive biosampling, lack of transportation, participant disinterest) and cultural factors (e.g., mistrust, cultural insensitivity, and language barriers) were the most frequently cited barriers to participation in research. A core strategy for successful recruitment entailed creating partnerships between research study staff and clinics and/or community organizations that provided prenatal services to pregnant women. Clinic staff and clinicians were able to help researchers to identify and to meet with potential participants and often aided in the process of recruitment (Hale et al., 2016; Leung et al., 2013; Promislow et al., 2004; van Delft et al., 2013; Webster et al., 2012).

Recruitment methods were more frequently described than retention in the included articles highlighting a substantial gap in the literature pertinent to supporting women to remain in long-term studies after their child is born. Key retention facilitators that were reported included flexibility with scheduling and accommodating the needs of participants, frequent communication, and culturally sensitive practices. Participant factors were also the most frequently cited barriers to retention, including loss of interest, pregnancy loss, relocation, multiple caregiver shifts, and substance use/mental health problems. Among more vulnerable, hard-to-reach women, decreasing participant burden by maximizing convenience (e.g., coinciding study assessments with prenatal care visits, home visits and assessments, alternative meeting arrangements), increasing frequency of communication to maintain contact with participants and personalizing messaging, providing practical resources and services (e.g., well-baby checkups, medical care, baby photographs, and baby presents), and minimizing barriers by providing transportation and childcare were all found to assist in recruitment and support retention efforts (Bandstra, 1992; Robles et al., 1994; Streissguth & Giunta, 1992).

Promoting trust and confidence between researchers and participants is critical to the success of enrolling and engaging pregnant women in long term studies, and especially important for retaining substance-using populations (Bandstra, 1992) and for those participants who are facing serious life events and interpersonal problems (Robles et al., 1994). Robles (1994) found developing procedures that established and maintained rapport helped to engage women who were experiencing depression and isolation and resulted in a twofold increase in participation. Creating partnerships with professionals at community, state, and federal agencies that serve the needs of substance-using pregnant women was found to be helpful in overcoming some of the legal challenges as well as to increase access to essential services and resources. Although direct recruitment strategies were the most effective for engaging potential participants, providers, and community stakeholders (Daniels et al., 2006; Manca et al., 2013; Monk et al., 2013; Morton et al., 2014; Richiardi et al., 2007), employing a variety of methods that combine direct, indirect, and third party marketing practices have been found to bring greater awareness about the study to the individual, clinic, and broader community in addition to substantially increasing completion rates (Robles et al., 1994).

Knowledge regarding the factors that impact participant involvement and decrease overall participant burden and implementing strategies that address these can increase recruitment and retention (Ayoub et al., 2018; Daniels et al., 2006; Neelotpol et al., 2016; van Delft et al., 2013). Recruitment staff can appeal to participant motivators (e.g., fostering healthy habits). In addition, recruitment staff can offer solutions to assist participants in overcoming concerns and barriers by offering incentives or by adapting the study design (e.g., to be less invasive). Also, the focus of sustaining relationships can help with study retention, including the development of protocols for contacting, following-up and tracking participants. It is important to note that postpartum and early childhood are challenging periods for families to stay in research due to competing demands, especially for medically fragile infants. Therefore, tailoring strategies to the specific needs of pregnant women and administering them in a flexible way is needed. An identified researcher, who becomes the “face” of the study and has the motivation and autonomy to employ those methods, is critical for longer term retention.

Adequate representativeness of the target population, including hard-to-reach and traditionally under-represented groups, is essential for generalizability of results. Understanding cultural norms, values, and language is crucial when establishing working relationships with diverse populations. Particular attention should be paid to fostering relationships between researchers and participants to retain representative cohorts (Neelotpol et al., 2016). For example, researchers’ sensitivity to cultural norms and practices was extremely important for securing the confidence of participants and establishing trust, since cultural norms influence the attitudes that participants hold toward research in general. Cultural competence combined with an embodied practice of humility among the research staff is crucial for recruitment of vulnerable populations, including racial/ethnic minorities, immigrant and refugee groups (Greene-Moton & Minkler, 2019). Moreover, availability of materials in non-dominant languages are also beneficial, yet it can be associated with substantial resources and cost.

Strengths and Limitations

The recommendations emerging from this scoping review should be viewed in light of its strengths and potential limitations. The results found in this review reflect the heterogeneity of existing studies including the wide variation in subject demographic, socioeconomic status, geographical locations, population groups, and recruitment settings and approaches. Other reviews studying this topic were largely conducted in the United States limiting their generalizability (Booker et al., 2011). Furthermore, while other reviews examined recruitment and retention of pregnant women in clinical studies (Frew et al., 2014) or focused primarily on the participant factors that influence study involvement (van der Zande et al., 2018), this review offers a wider scope of study practices that may serve as facilitators and/or barriers in longitudinal birth cohort studies. Therefore, the lessons learned from this review are highly relevant and applicable to future large population studies.

It should also be acknowledged that approaches to recruitment and retention may vary based on the geographical region, target population, and local context, and, thus, should be applied with scrutiny and attention to cultural factors. For example, a site with high representation of ethnic minorities and/or non-English speakers might need to utilize bilingual research assistants of similar racial and ethnic background and translate study documents into the non-dominant language (Chasan-Taber et al., 2009). Those activities might be associated with additional costs and resources that are not applicable or beneficial to all sites. Due to considerable heterogeneity in study durations, it is important to consider that different strategies may be required for longer term versus shorter term studies. Second, we cannot exclude a potential role of publication bias in the compilation of articles included in this review (Onishi & Furukawa, 2014). For example, studies with recruitment and retention successes rather than failures may be more likely to be submitted and represented in the published literature. Consequently, it is not surprising that we found more facilitators than barriers reported in the literature. Third, this scoping review primarily focused on recruitment and retention strategies from the researchers’ perspective. Equally important is the potential participant and community perspective, which needs to be carefully ascertained and incorporated into the study design. Last, studies that lacked substantive detail about recruitment and retention methodology and analysis of the facilitators or barriers involved in engaging pregnant women in research were excluded. This resulted in the omission of some longitudinal studies that recruited at-risk pregnant women. Consequently, this review is representative of recruitment and retention strategies for general population pregnant women that are also applicable to hard-to-reach groups. The paucity of studies included in this review on the impact of prenatal drug exposure using longitudinal research designs points to a substantial gap in the recruitment and retention literature. Future studies involving at-risk pregnant women should elaborate on the specific needs and challenges of engaging these groups in research, which are likely to differ from the general population of pregnant women.

4. Conclusion