Abstract

Objective:

Variability of Cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, including racial difference, is not fully accounted for by the variability of traditional CVD risk factors. We used a multiple biomarker model as a framework to explore known racial differences in CVD burden.

Design:

We measured associations between accelerated aging (AccA) measured by a combination of biomarkers, and cardiovascular morbidity and all-cause mortality using data from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study (CARDIA). AccA was defined as the difference between biological age, calculated using biomarkers with the Klemera and Doubal method, and chronological age. Using logistic regression, we assessed overall and race-specific associations between AccA, CVD, and all-cause mortality.

Results:

Among our cohort of 2959 Black or White middle-aged adults, after adjustment, a one-year increase in AccA was associated with increased odds of CVD (Odds Ratio (OR) = 1.04; 95% CI: 1.02, 1.06), stroke (OR = 1.12; 95% CI: 1.07, 1.17), and all-cause mortality (OR = 1.05; 95% CI: 1.02, 1.08). We did not find significant overall racial differences, but we did find race by sex differences where Black men differed markedly from White men in the strength of association with CVD (OR = 1.06, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.12).

Conclusions:

We provide evidence that AccA is associated with future CVD.

Keywords: Health disparities, accelerated aging, biological aging, cardiovascular disease

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD), including myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure, are an immense burden of morbidity, mortality, and healthcare related costs on the U.S. population, with a disproportionate burden on Blacks (Benjamin et al. 2017). Stroke especially has been found to disparately affect Blacks as far back as the 1960’s and 1970’s so that even as stroke incidence and mortality has improved over time it remains more problematic and deadly for Blacks (Howard 2013). Although important risk factors for CVD such as hypertension, high cholesterol, smoking, obesity, age, and physical inactivity are known, these traditional risk factors do not account for racial differences in CVD risk (Khot et al. 2003; Greenland et al. 2003) or the racial differences in traditional CVD risk factors (Mendis and Banerjee 2010). Consequently, multiple biomarker prediction is gaining popularity in accounting for the variation missed by traditional risk factors (Wang et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2007). Multiple biomarker measures such as biological dysregulation such as allostatic load and biological are also associated with social factors that affect health (Forrester et al. 2019; Brooks et al. 2014; Seeman et al. 2014) making them natural options for better understanding racial differences in health outcomes such as CVD.

Blacks in the US are more likely to face chronic stressors due to their minority status (Williams, Priest, and Anderson 2016) and many of these stressors stem from one fundamental cause – racism (Phelan and Link 2015). Both structural racism, or institutional, historical, cultural, and social dynamics that advantage Whites and cumulatively and chronically disadvantage people of color; and interpersonal racism, such as prejudice, and personal bias have been found to negatively affect health outcomes such as cardiovascular disease, birth outcomes, hypertension, and abdominal obesity (Williams and Mohammed 2013; Gee and Ford 2011; Goosby, Cheadle, and Mitchell 2018; Bailey et al. 2017). The cumulative effect of physiological responses to these chronic stressors appears to translate into disparate health outcomes (Sternthal, Slopen, and Williams 2011). Due to these established associations it seems likely that a cumulative biological measure that is associated with stress would be more strongly predictive of outcomes such as cardiovascular disease and mortality in minority populations since minority populations deal with more chronic stress causing “repeated hits” on the bodily systems that respond to stress. Indeed, biological age, measured by an index of multiple clinical biomarkers including, but not limited to, C-Reactive Protein, Serum Creatinine, Glycosylated Hemoglobin, and Forced Expiratory Volume (one second), has been shown to mediate the relationship between Black race and mortality with race no longer an independent predictor of mortality in statistical models that included biological age (Levine and Crimmins 2014). We recently showed that accelerated aging, defined as biological age based on clinical biomarkers minus chronological age, similarly, was significantly higher for Blacks than Whites and was associated with psychosocial stressors (Forrester et al. 2019). Herein, we investigate whether accelerated aging (AccA) is associated with future cardiovascular events and mortality and whether there are racial differences in that association. As CVD and mortality outcomes are generally moderated by sex, sex by race differences are likely. Research has shown that socioeconomic health disadvantages were worse for women and that certain predictors such as obesity are growing at a faster rate among Black women (Geronimus et al. 2010). The original work on “weathering” (accelerated biological decline) was illustrated with a cohort of women (Geronimus 1996) and subsequent weathering literature using allostatic load showed that Black women had the highest burden of allostatic load (Geronimus et al. 2006). Given this and previous research in CARDIA showing race and sex differences in 5-year change in blood pressure (Knutson et al. 2009), sex differences in left ventricular structure (Kishi et al. 2015), an the association between SES and blood pressure (Janicki-Deverts et al. 2012), and women having higher biological age (Forrester et al. 2019) we hypothesize that there will be a race-sex interaction in the association between CVD and mortality and AccA with Black women having the most risk.

Materials and Methods

Cohort description

CARDIA is a multicenter longitudinal study of 5,114 Black or White individuals aged 18 to 30 years old in 1985–86. Following the baseline examination at year 0 (Y0) in 1985–86, examinations were conducted at Y2, Y5, Y7, Y10, Y15, Y20, Y25, and Y30 (2015–16) with yearly interim phone contacts to ascertain vital status and hospitalizations through year 33. At baseline, CARDIA participants had to be free from chronic disease and disability and were selected by stratified random sampling so that there would be approximately equal numbers of Blacks and Whites, men and women, younger and older individuals, and those with higher vs. lower educational attainment at each of the four CARDIA field centers in Birmingham, AL; Chicago, IL; Minneapolis, MN; and Oakland, CA (Friedman et al. 1988). Biological age was calculated at year 20 so we excluded 2,155 participants who did not attend the Y20 exam (N=1565, of whom 175 had died), attended but did not have complete biological data at Y20 (N=565), or attended and had full biological data but had a cardiovascular event prior to 2007 for a present study sample size of 2,959 individuals. Participants were excluded if they were missing biological variables or covariate data.

Measures

Biological age/Accelerated aging

“Accelerated Aging” (AccA) was defined as the difference between biological age (BA) and chronological age (CA) (AccA = BA – CA). Thus, a positive value indicates that a person is biologically older than their CA and a negative value indicates they are biologically younger than their CA. BA was calculated with the Klemera & Doubal Method (KDM) (Klemera and Doubal 2006) which minimizes the distance between m regression lines and m biomarker points, within an m dimensional space of all biomarkers through the equation:

| (1) |

In equation 1, kj is the slope of the regression of biomarker j on CA, qj is the intercept, xj is the value of biomarker j, m is the number of biomarkers, and sj is the root mean squared error of the regression of biomarker j on CA. Thus, BA is a weighted average of expected biomarker values minus the biomarker value at CA that is determined through regressing each biological marker on CA (Forrester et al. 2019). KDM has been shown to be the best method of BA computation compared to multiple linear regression and principal components analysis (Cho, Park, and Lim 2010).

We selected biomarkers based on their association with aging, availability in CARDIA, and significant association with CA in CARDIA: total and HDL cholesterol (mg/dL), fasting glucose (mg/dL), waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) (mg/L), forced expiratory volume-1 second (FEV1/h2) (liters), and mean arterial pressure (MAP) (mmHg) ((Friedman et al. 1988) and (Lakoski et al. 2006) have more detail on biomarker measurement). We used biomarkers from Y20 (2005–2006, ages 38–55 years). We measured biological age at Y20 because currently we have no outcome data beyond year 33 and we sought enough time for outcomes to occur while still measuring biological age at a chronological age (around middle age) where some cumulative dysregulation has likely occurred.

Morbidity and mortality

Morbidity and mortality events are determined through annual participant contacts, death certificates, and relevant medical and hospital records. Events are adjudicated according to established protocol (The CARDIA Endpoints Surveillance and Adjudication Committee (ESAS) 2012), with details regarding outcome ascertainment published elsewhere (Bibbins-Domingo et al. 2009). In examining the temporal relationship between AccA and morbidity and mortality, we only used endpoints from 2007 onward (1 year after the Y20 exam to allow for time between AccA measurement and outcomes) and ending in 2018, excluding participants with events before 2007. Our morbidity endpoints were myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, non-MI acute coronary syndrome, chronic heart failure, stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter, and death attributed to CVD.

Race and Sex

Race was self-reported in 1985–1986 and verified at Y2 as Black/African American or White/Caucasian; ethnicity was not ascertained. Sex was self-reported at baseline as male or female.

Additional covariates

Smoking was defined as never/former smokers versus current smokers at Y20. Alcohol use was defined as mL alcohol consumed/day in a typical week in the past year, at Y20. Physical activity was assessed with the CARDIA Physical Activity History Questionnaire which measures leisure-time physical activity in 13 categories over the last 12 months. We used total exercise score at Y20 including both moderate and vigorous activities and expressed in exercise units (EU), where 300 EU was roughly equivalent to 30 minutes of activity on 5 days (Jacobs et al. 1989). Longer duration and higher intensity of exercise equal more EUs.

Statistical analysis

We compared biological age, chronological age, accelerated aging, outcomes, and covariates by race using t-tests and chi-square analysis. Most morbidity endpoints (listed above) had a prevalence ≤1% between 2007 and 2018 so we created a composite CVD endpoint. CVD was modeled as present or absent where present indicated that at least one cardiovascular endpoint was adjudicated between 2007 and 2018. This is based on the American Heart Association’s definition of CVD (American Heart Association 2017). Although hypertension and diabetes were prevalent in CARDIA, we omitted them as individual outcomes because serum glucose and mean arterial pressure are included in the biological age equation. Our analysis was completed separately for the following outcomes – CVD, stroke, and all-cause mortality. Although stroke is included in the CVD definition, we analyzed stroke as a separate endpoint because it is historically very racially disparate (Oh 1971; Heyman et al. 1971; Howard 2013). Given the low prevalence of most outcomes, we used Firth logistic regression models using penalized maximum likelihood estimation for rare events to address the small sample bias that affects logistic regression (Firth 1993). Since we hypothesize that Blacks will have a stronger association between AccA and outcomes we included an interaction term for AccA and race. In addition, since sex by race differences in cardiovascular factors have previously been found in CARDIA, we included a sex by race interaction term. For each of the three outcomes we first ran an unadjusted model and then we ran a fully adjusted model for the main association, a fully adjusted model for each interaction, and a fully adjusted model stratified by race. Fully adjusted models were adjusted for sex, race, chronological age, study site, smoking status, ML of alcohol per week, and exercise score. All analyses were done using Stata.

Sensitivity analysis

Our main analysis was a complete case analysis including only those who had complete biological and covariate data at Y20. Among participants with a CVD outcome, 34% were missing biological data at Y20. And among participants who died between 2007 and 2018, 75% were missing biological data at Y20; to examine whether these exclusions influenced our results, we completed a sensitivity analysis using multiple imputation with the multivariate normal distribution for those who were lost due to attrition at Y20. We created 10 sets of imputed data and pooled the results across the 10 datasets. We then used the imputed datasets in the KDM calculations and conducted the same analyses from the main analysis using the imputed dataset. The sensitivity analysis showed that the missingness in our main analysis slightly attenuated the results, but direction of association and overall significance did not change. In comparing those who were missing from our sample with those who were present at baseline we found that the most likely to be missing were Blacks (38%) and in particular Black men (44%) as well as those with less than a high school education (47%).

Results

Cohort description

Our sample consisted of 2,984 Black or White participants with a mean chronological age of 45 years in 2005–2006 (Y20 -Table 1). Overall, 45% of the sample was Black. Among Blacks, 62% were women and among Whites, 53% were women

Table 1.

Means and Proportions of Demographics, Biological Age, Biomarkers, and Outcomes at Year 20, Overall and by Race/Sex Categories: CARDIA 2005–2006

| Total (n = 2984) m (sd) or % | Black Women (n = 825) m (sd) or % | Black Men (n = 505) m (sd) or % | White Women (n = 885) m (sd) or % | White Men (n = 769) m (sd) or % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45.3 (3.6) | 44.6 (3.8) | 44.6 (3.8) | 45.8 (3.4) | 45.8 (3.4) | |

| Biological Age | 45.1 (9.2) | 47.3 (9.9) | 46.4 (9.0) | 43.5 (8.40) | 43.6 (8.8) |

| Accelerated Aging | −0.2 (8.5) | 2.7 (8.6) | 1.8 (8.4) | −2.3 (7.6) | −2.1 (8.1) |

| Current Smoker | 17.7% | 21.0% | 27.3% | 12.5% | 14.1% |

| mL Alcohol/week | 10.9 (21.9) | 5.3 (14.6) | 14.1 (30.8) | 10.0 (15.2) | 15.9 (26.2) |

| Exercise score (EU) | 343.2 (274.7) | 227.9 (220.4) | 410.3 (330.5) | 343.9 (256.1) | 421.3 (265.5) |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 186.3 (34.8) | 185.1 (34.7) | 183.4 (37.1) | 187.0 (31.7) | 188.8 (36.6) |

| HDL Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 54.3 (16.6) | 57.5 (15.8) | 49.4 (15.3) | 61.4 (16.8) | 45.9 (12.8) |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 97.3 (24.3) | 98.1 (30.8) | 101.6 (27.5) | 91.8 (14.8) | 100.1 (22.0) |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 2.7 (4.5) | 4.2 (5.5) | 2.5 (4.7) | 2.4 (4.2) | 1.4 (2.4) |

| FEV1/h2 (liters) | 3.1 (0.8) | 2.4 (0.5) | 3.2 (0.6) | 2.9 (0.5) | 3.9 (0.6) |

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 87.3(12.0) | 90.1 (13.0) | 92.3 (11.3) | 81.6 (10.5) | 87.5 (10.2) |

| Outcomes [incidence rate 2007–2018 (average time to outcome, in years)] | |||||

| Cardiovascular Disease | 0.007 (9.7) | 0.009 (8.6) | 0.010 (9.5) | 0.004 (9.8) | 0.007 (9.6) |

| Stroke | 0.001 (9.9) | 0.002 (9.9) | 0.002 (9.9) | 0.0002 (10.0) | 0.001 (10.0) |

| Mortality | 0.001 (10.0) | 0.001 (10.0) | 0.001 (10.0) | 0.001 (10.0) | 0.001 (10.0) |

FEV1/h2 = Forced expiratory volume in 1 second/height2; EU = Exercise Units

CVD includes myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, non-MI acute coronary syndrome, chronic heart failure, stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter, and death attributed to CVD

Chronological age was similar by race. For the biomarkers used to estimate biological age (BA), Whites had significantly higher total cholesterol than Blacks (187.8 mg/dL vs 184.4 mg/dL), and HDL cholesterol (54.2 mg/dL vs 54.4 mg/dL) and waist-to-hip ratio (0.83 for both races) did not differ significantly by race. All other biological variables were significantly worse for Blacks than Whites. Overall means for each biomarker were 186.3 mg/dL (total cholesterol), 54.3 mg/dL (HDL cholesterol), 97.3 mg/dL (glucose), 0.83 (WHR), 2.7 mg/L (CRP), 3.1 liters (FEV1/h2), and 87.3 mmHg (MAP).

Predictors.

Mean BA in the sample was 45 years and was higher among Blacks than Whites (47 years versus 43 years). Mean AccA was plus 2.4 years among Blacks and minus 2.2 years among Whites. Within race-sex groups AccA was highest among Black women (2.7 years) and Black men (1.8 years) and lowest among White women (−2.3 years) and White men (−2.1 years). The proportion of current smokers was higher for Blacks than Whites (highest among Black men at 27.3% and lowest among White women at 10%) and alcohol consumed in a week was higher among Whites than Blacks (highest among White men at 15.9 mL per week and lowest among Black women at 5.3 mL per week) indicating that more Blacks reported being current smokers but Whites reported drinking more alcohol per week. Whites report exercising longer and more intensely than Blacks, on average (highest among White men at 421.3 EUs and lowest among Black women at 227.9 EUs).

There were 220 participants (7%) with a CVD event after 2007 and 59 deaths (2%). CVD events were significantly higher among Black men (10%) and Black Women (9.0%) compared with White men (7.4%) and White women (4.2%) (Chi2 = 22.6, p<0.001). Mortality percentage was similar for each group (Black men = 2.8%; Black women = 1.8%; White men = 2.1%; White women = 1.6%) but slightly higher for Black men, though not significantly so (Chi2 = 2.5, p = .473) Although the number of deaths was similar by race, the prevalence of CVD was higher among Blacks than among Whites (8% vs. 5%) (see supplemental table 1). The incidence of stroke between 2007 and 2016 was 1% overall and higher among Blacks than Whites (2% vs. 0.4%) with White women and men having stroke incidence below 1% (0.2% and 0.6% respectively) and Black women and men having stroke incidence higher than 2% (2.3% and 2.2% respectively).

AccA and cardiovascular events

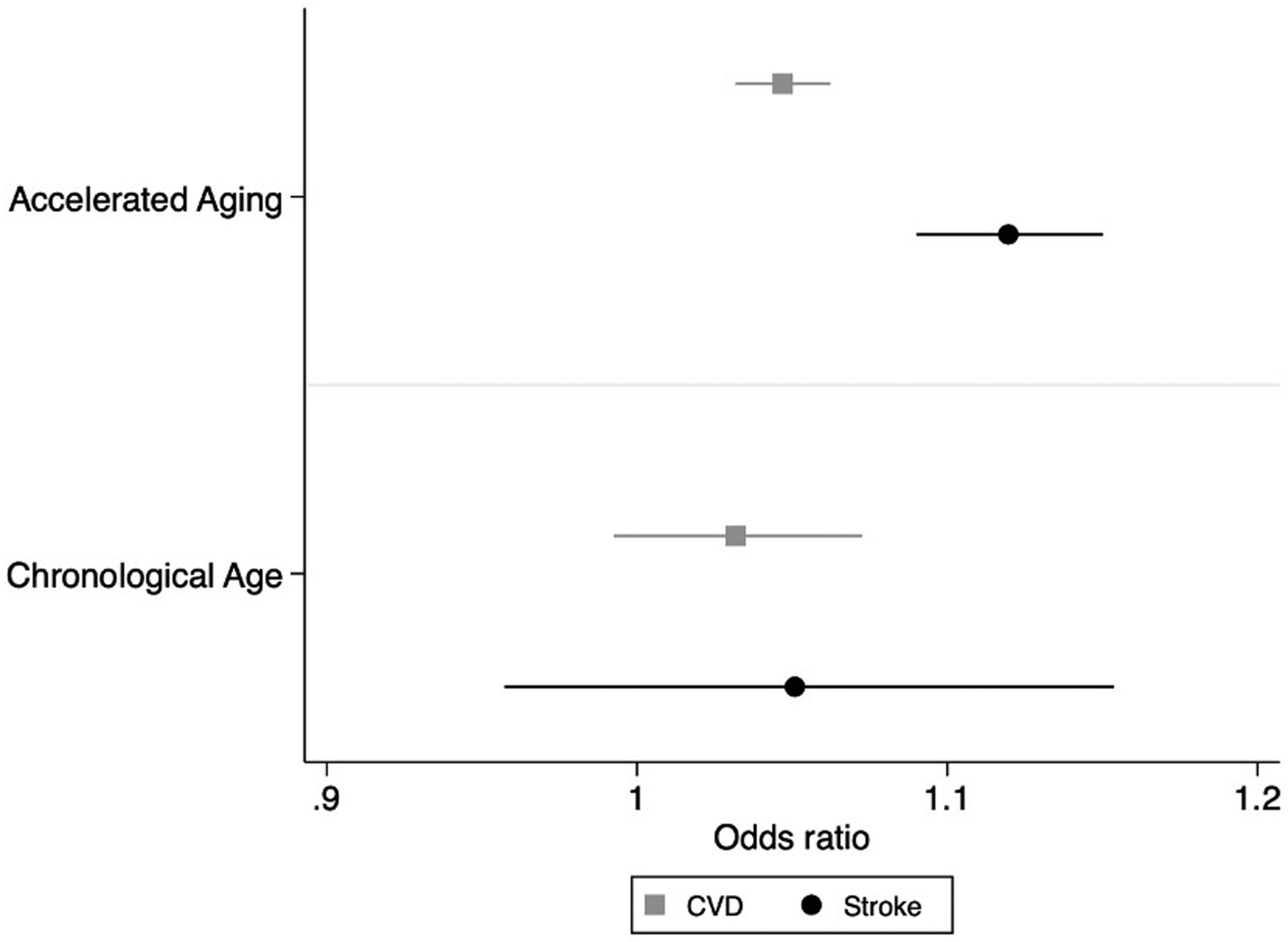

In unadjusted analysis AccA was significantly associated with higher odds of CVD (OR: 1.04, 95% CI: 1.03, 1.06) (Table 2). After adjustment, the relationship remained the same (OR: 1.04, 95% CI: 1.03, 1.06). Similarly, in unadjusted analysis AccA was significantly associated with stroke (OR: 1.12, 95% CI: 1.09, 1.15) and remained the same after adjustment (OR: 1.12, 95% CI: 1.07, 1.17).

Table 2.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Odds Ratio for Each Outcome Associated with a One-Year increment in Accelerated Aging: CARDIA, 2007–2018

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |

|---|---|---|

| Endpoint | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

| Cardiovascular Disease | 1.04 (1.03, 1.06) | 1.04 (1.02, 1.06) |

| Stroke | 1.12 (1.09, 1.15) | 1.12 (1.07, 1.17) |

| All-cause mortality | 1.06 (1.03, 1.08) | 1.05 (1.02, 1.08) |

Adjusted for sex, race, chronological age, site, smoking status, mL alcohol per week, and exercise score. CVD and stroke also adjusted for presence of prior outcomes and mortality adjusted for prior CV outcomes.

For both CVD and stroke analyses, AccA was a better predictor of cardiovascular outcomes than chronological age (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Odds of cardiovascular disease and stroke predicted by each one-year increment in accelerated aging and chronological age, CARDIA, 2007–2018.

AccA and mortality

Unadjusted (OR: 1.06, 95%CI: 1.03, 1.08) and adjusted (OR: 1.05, 95% CI: 1.02, 1.08) analysis of AccA and mortality showed a similar significant relationship with AccA at Y20 predicting increased odds of mortality 1–12 years later. Although AccA still significantly predicted mortality after adjustment for chronological age, chronological aging also significantly predicted mortality with a slightly higher odds ratio (OR (AccA) = 1.05, 95% CI: 1.02, 1.08 vs. OR (age) = 1.13, 95% CI: 1.04, 1.23).

Race and sex differences

Interactions.

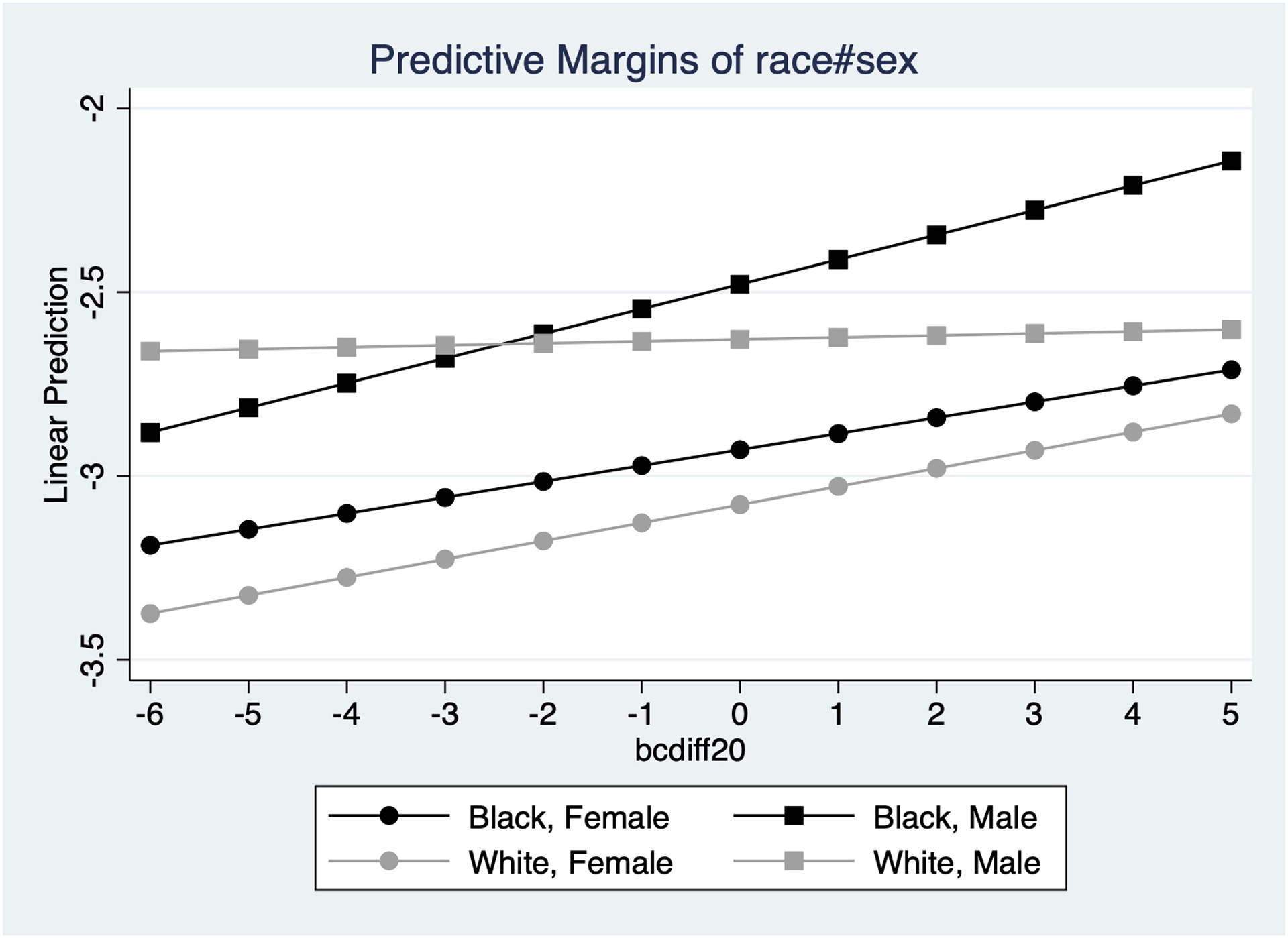

The fully adjusted model predicting CVD with an interaction term between race and AccA revealed no significant difference between the odds ratios for Blacks compared with Whites (interaction term: OR: 1.03, 95% CI: 1.00, 1.06). Similar, non-significant results were found for stroke and mortality (Table 4). The adjusted model predicting CVD including an interaction term between sex, race, and AccA, showed that the odds of having a CVD outcome for each one-year increase in AccA was significantly higher for Black men compared to White men (interaction term: OR: 1.06, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.12) (Figure 2). White women and Black women also had higher odds of a CVD outcome compared to White men but not significantly so (Table 4). No significant differences were found for stroke or mortality.

Table 4.

Interaction Terms (Odds Ratios) for each Outcome for Each Outcome Associated with a one-year increase in AccA, CARDIA 2007–2018

| Race × AccA | Race × Sex × AccA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White OR (95% CI) | Black OR (95% CI) | White Men OR (95% CI) | White Women OR (95% CI) | Black Men OR (95% CI) | Black Women OR (95% CI) | |

| REF | 1.03 (1.00, 1.06) | REF | 1.04 (0.99, 1.10) | 1.06 (1.01, 1.12) | 1.04 (1.00, 1.08) | |

| Stroke | REF | 1.04 (0.95, 1.15) | REF | 0.98 (0.84, 1.15) | 1.06 (0.95, 1.17) | 1.00 (0.90, 1.11) |

| All-Cause Mortality | REF | 1.00 (0.95, 1.06) | REF | 1.01 (0.93, 1.10) | 1.01 (0.94, 1.09) | 1.00 (0.94, 1.07) |

Figure 2.

Predicted odds of cardiovascular disease for each one-year increment in accelerated aging by race and sex, CARDIA, 2007–2018.

Stratified Analyses.

The race-stratified analysis revealed a significant relationship between AccA and each of the three outcomes among Blacks. (OR: 1.05, 95% CI: 1.03, 1.08 for CVD; OR: 1.12, 95% CI: 1.08, 1.16 for stroke; OR: 1.05, 95% CI: 1.02, 1.09 for mortality) (Table 3). For Whites, the association was significant for mortality (OR: 1.05, 95% CI: 1.01, 95% CI: 1.02, 1.10), but only marginally significant for CVD and stroke. See supplemental table 2 for all adjusted and unadjusted race-stratified results.

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds Ratio for Each Outcome Associated with a One-Year Increment in Accelerated aging by Race, CARDIA, 2007–2018

| Race | ||

|---|---|---|

| Endpoint | Black OR (95% CI)a | White OR (95% CI)a |

| Cardiovascular Disease | 1.05 (1.03, 1.08) | 1.02 (1.00, 1.05) |

| Stroke | 1.12 (1.08, 1.16) | 1.03 (0.93, 1.14) |

| Death | 1.05 (1.02, 1.09) | 1.05 (1.01, 1.10) |

Adjusted for sex, chronological age, site, smoking status, mL alcohol per week, and exercise score. CVD and stroke also adjusted for presence of prior outcomes and mortality adjusted for prior CV outcomes.

Discussion

We had hypothesized that AccA would be associated with increased odds of CVD and mortality and that these relationships would be more detrimental to Blacks than Whites. Further we hypothesized that there would be a race by sex interaction and that Black women would have the highest risk for CVD and mortality based on accelerated aging. We found mixed support for these hypotheses. The associations we hypothesized appear to exist overall and within each racial group (albeit marginally for CVD and mortality in Whites). Although we did find a race-sex interaction, it was Black men who were at the highest risk of CVD compared to other race-sex groups, and there was no difference by group for stroke or mortality.

AccA and morbidity/mortality

Our findings of an increase in the risk of CVD, stroke, and mortality with each 1-year increase in AccA establishes the proof of concept of AccA as a predictor. The timing of the variables used, AccA at exam year 20 and health outcomes between one and twelve years later, precludes reverse causation. Levine and Crimmins (Levine and Crimmins 2014) used the same method to compute biological age that we used and found an association between biological age and mortality among Blacks in particular. In our study, not only is biological age a predictor of mortality, the difference between biological age and chronological age predicts mortality. For example, the odds of having a CVD event for someone who is 10 years older biologically than chronologically are about 1.48 (1.04 increase per year over 10 years) compared to someone whose biological age coincides with their chronological age.

Race and morbidity/mortality

Our race-stratified analysis showed that the association between AccA and CVD were significant among Blacks but not clearly so among Whites. It is well known that Blacks have a higher prevalence of CVD, CVD related mortality, and risk factors for CVD (e.g. hypertension, diabetes, high cholesterol, inactivity, smoking) and poorer outcomes (Mensah et al. 2005). Blacks also develop some CVD at an earlier chronological age than Whites (Jones et al. 2000) which provides timely context for our findings. Our findings suggest that the mechanism of AccA as a predictor may work similarly in Blacks as in Whites, thus may be a useful tool for studying health disparities. These findings are especially important given that AccA appears to predict cardiovascular outcomes better than chronological age. Our finding that the association between AccA is significantly more detrimental for Black men compared to White men may be important to future efforts to eradicate this disparity. We have previously shown that AccA is associated with psychosocial stress (Forrester et al. 2019). Future research should explicitly test whether AccA is a viable mechanism for the known associations between social stress and CVD so that interventions aimed at stress reduction and coping can be tested to reduce the disparity.

Limitations and strengths

Our results should be understood in light of limitations. Our sample was relatively healthy thus limiting generalizability to unhealthy populations. Also, the low event rates limits power to detect associations with individual events such as myocardial infarction and reduces power for stratified analysis. It also may limit our power to identify the hypothesized racial differences in overall strengths of associations. There was also some differential missingness however our results show that Blacks have higher average AccA and that AccA is highest among those with less than a high school education, so these differences are likely to attenuate our results. Additionally, our sensitivity analysis with imputation showed overall mean biological age was slightly higher and chronological age was similar, so overall mean AccA was slightly higher and the main associations were slightly stronger. The strengths of our study include longitudinal data allowing for temporal relationships and the use of a validated method of biological age computation.

Conclusion

It is important to understand whether AccA is modifiable and how in order for it to be a viable intervention target for health disparities research. Future research should focus on this, as well as on AccA as a potential mechanism to explain racial disparities in CVD outcomes. The ability of AccA to predict cardiovascular outcomes better than chronological age is an important reason to develop the concept, especially among minority populations where we do not seem to be gaining ground in eliminating CVD disparities (Cruz-Flores et al. 2011; Adams et al. 2018).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study (CARDIA) is supported by contracts HHSN268201800003I, HHSN268201800004I, HHSN268201800005I, HHSN268201800006I, and HHSN268201800007I from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI).

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: We have no real or potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Sarah N. Forrester, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Department of Population and Quantitative Health Sciences, Worcester, MA, USA,

Veronique L. Roger, Mayo Clinic, Division of Circulatory Failure, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Rochester, MN USA,

Roland J. Thorpe, Jr., Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Department of Health, Behavior, and Society, Baltimore, MD USA,

Catarina I. Kiefe, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Department of Population and Quantitative Health Sciences, Worcester, MA, USA,

References

- Adams RJ, Ellis C, Magwood G, Kindy MS, Bonilha L, Lackland DT, and Wissdom Investigators. 2018. “Commentary: Addressing Racial Disparities in Stroke: The Wide Spectrum Investigation of Stroke Outcome Disparities on Multiple Levels (WISSDOM).” Ethn Dis 28 (1):61–8. doi: 10.18865/ed.28.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Heart Association. 2019. “What is Cardiovascular Disease?”, Accessed 01/04/2019.

- Bailey, Zinzi D, Krieger Nancy, Agénor Madina, Graves Jasmine, Linos Natalia, and Bassett Mary T. 2017. “Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions.” The Lancet 389 (10077):1453–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, Deo R, de Ferranti SD, et al. 2017. “Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2017 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association.” Circulation 135 (10):e146–e603. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibbins-Domingo K, Pletcher MJ, Lin F, Vittinghoff E, Gardin JM, Arynchyn A, Lewis CE, Williams OD, and Hulley SB. 2009. “Racial differences in incident heart failure among young adults.” N Engl J Med 360 (12):1179–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks KP, Gruenewald T, Karlamangla A, Hu P, Koretz B, and Seeman TE. 2014. “Social relationships and allostatic load in the MIDUS study.” Health Psychol 33 (11):1373–81. doi: 10.1037/a0034528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho IH, Park KS, and Lim CJ. 2010. “An empirical comparative study on biological age estimation algorithms with an application of Work Ability Index (WAI).” Mech Ageing Dev 131 (2):69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Flores S, Rabinstein A, Biller J, Elkind MS, Griffith P, Gorelick PB, Howard G, et al. 2011. “Racial-ethnic disparities in stroke care: the American experience: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association.” Stroke 42 (7):2091–116. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182213e24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth D 1993. “Bias Reduction of Maximum Likelihood Estimates.” Biometrika 80 (1):27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Forrester SN, Jacobs DR, Zmora R, Schreiner P, Roger VL, and I Kiefe C. 2019. “Racial Differences in Weathering and its Associations with Psychosocial Stress: The CARDIA Study.” SSM - Population Health 7. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman GD, Cutter GR, Donahue RP, Hughes GH, Hulley SB, Jacobs DR Jr., Liu K, and Savage PJ. 1988. “CARDIA: study design, recruitment, and some characteristics of the examined subjects.” J Clin Epidemiol 41 (11):1105–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee, Gilbert C, and Ford Chandra L. 2011. “Structural racism and health inequities: old issues, new directions.” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 8 (1):115–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus AT, Hicken M, Keene D, and Bound J. 2006. ““Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among blacks and whites in the United States.” Am J Public Health 96 (5):826–33. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.060749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus AT, Hicken MT, Pearson JA, Seashols SJ, Brown KL, and Cruz TD. 2010. “Do US Black Women Experience Stress-Related Accelerated Biological Aging?: A Novel Theory and First Population-Based Test of Black-White Differences in Telomere Length.” Hum Nat 21 (1):19–38. doi: 10.1007/s12110-010-9078-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus Arline T. 1996. “Black/white differences in the relationship of maternal age to birthweight: a population-based test of the weathering hypothesis.” Social science & medicine 42 (4):589–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goosby Bridget J, Cheadle Jacob E, and Mitchell Colter. 2018. “Stress-related biosocial mechanisms of discrimination and African American health inequities.” Annual Review of Sociology 44:319–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenland P, Knoll MD, Stamler J, Neaton JD, Dyer AR, Garside DB, and Wilson PW. 2003. “Major risk factors as antecedents of fatal and nonfatal coronary heart disease events.” JAMA 290 (7):891–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.7.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman Albert, Herbert R Karp Siegfried Heyden, Bartel Alan, Cassel John C, Tyroler Herman A, Cornoni J, Hames CG, and Stuart W. 1971. “Cerebrovascular disease in the bi-racial population of Evans County, Georgia.” Stroke 2 (6):509–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard Virginia J. 2013. “Reasons underlying racial differences in stroke incidence and mortality.” Stroke 44 (6_suppl_1):S126–S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs DR Jr., Hahn LP, Haskell WL, Pirie P, and Sidney S. 1989. “Validity and Reliability of Short Physical Activity History: Cardia and the Minnesota Heart Health Program.” J Cardiopulm Rehabil 9 (11):448–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janicki-Deverts Denise, Cohen Sheldon, Matthews Karen A, and Jacobs David R Jr. 2012. “Sex differences in the association of childhood socioeconomic status with adult blood pressure change: the CARDIA study.” Psychosomatic medicine 74 (7):728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DW, Sempos CT, Thom TJ, Harrington AM, Taylor HA Jr., Fletcher BW, Mehrotra BD, Wyatt SB, and Davis CE. 2000. “Rising levels of cardiovascular mortality in Mississippi, 1979–1995.” Am J Med Sci 319 (3):131–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khot UN, Khot MB, Bajzer CT, Sapp SK, Ohman EM, Brener SJ, Ellis SG, Lincoff AM, and Topol EJ. 2003. “Prevalence of conventional risk factors in patients with coronary heart disease.” JAMA 290 (7):898–904. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.7.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi Satoru, Gisela Teixido-Tura Hongyan Ning, Bharath Ambale Venkatesh Colin Wu, Almeida Andre, Choi Eui-Young, Gjesdal Ola, Jacobs David R, and Schreiner Pamela J. 2015. “Cumulative blood pressure in early adulthood and cardiac dysfunction in middle age: the CARDIA study.” Journal of the American College of Cardiology 65 (25):2679–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemera P, and Doubal S. 2006. “A new approach to the concept and computation of biological age.” Mech Ageing Dev 127 (3):240–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson Kristen L, Van Cauter Eve, Rathouz Paul J, Yan Lijing L, Hulley ephen B, Liu Kiang, and Lauderdale Diane S. 2009. “Association between sleep and blood pressure in midlife: the CARDIA sleep study.” Archives of internal medicine 169 (11):1055–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakoski SG, Herrington DM, Siscovick DM, and Hulley SB. 2006. “C-reactive protein concentration and incident hypertension in young adults: the CARDIA study.” Arch Intern Med 166 (3):345–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.3.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine ME, and Crimmins EM. 2014. “Evidence of accelerated aging among African Americans and its implications for mortality.” Soc Sci Med 118:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendis Shanthi, and Banerjee A. 2010. “Cardiovascular disease: equity and social determinants.” Equity, social determinants and public health programmes 31:48. [Google Scholar]

- Mensah GA, Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Greenlund KJ, and Croft JB. 2005. “State of disparities in cardiovascular health in the United States.” Circulation 111 (10):1233–41. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158136.76824.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh, SHIN JOONG. 1971. “Cerebro-vascular diseases in Negroes.” Journal of the National Medical Association 63 (2):93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan Jo C, and Link Bruce G. 2015. “Is racism a fundamental cause of inequalities in health?” Annual Review of Sociology 41:311–30. [Google Scholar]

- Seeman M, Stein Merkin S, Karlamangla A, Koretz B, and Seeman T. 2014. “Social status and biological dysregulation: the “status syndrome” and allostatic load.” Soc Sci Med 118:143–51. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternthal MJ, Slopen N, and Williams DR. 2011. “RACIAL DISPARITIES IN HEALTH: How Much Does Stress Really Matter?” Du Bois Rev 8 (1):95–113. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X11000087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The CARDIA Endpoints Surveillance and Adjudication Committee (ESAS). 2012. “CARDIA Endpoint Events Manual of Operations.” In.

- Wang TJ, Gona P, Larson MG, Levy D, Benjamin EJ, Tofler GH, Jacques PF, et al. 2007. “Multiple biomarkers and the risk of incident hypertension.” Hypertension 49 (3):432–8. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000256956.61872.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang TJ, Gona P, Larson MG, Tofler GH, Levy D, Newton-Cheh C, Jacques PF, et al. 2006. “Multiple biomarkers for the prediction of first major cardiovascular events and death.” N Engl J Med 355 (25):2631–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Priest N, and Anderson NB. 2016. “Understanding associations among race, socioeconomic status, and health: Patterns and prospects.” Health Psychol 35 (4):407–11. doi: 10.1037/hea0000242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams David R, and Mohammed Selina A. 2013. “Racism and health I: Pathways and scientific evidence.” American behavioral scientist 57 (8):1152–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.