Abstract

The respiratory tract is a vital, intricate system for several important biological processes including mucociliary clearance, airway conductance, and gas exchange. The Wnt signaling pathway plays several crucial and indispensable roles across lung biology in multiple contexts. This review highlights the progress made in characterizing the role of Wnt signaling across several disciplines in lung biology, including development, homeostasis, regeneration following injury, in vitro directed differentiation efforts, and disease progression. We further note uncharted directions in the field that may illuminate important biology. The discoveries made collectively advance our understanding of Wnt signaling in lung biology and have the potential to inform therapeutic advancements for lung diseases.

Subject terms: Cell signalling, Lung cancer, Developmental biology, Respiration

Cody Aros, Carla Pantoja, and Brigitte Gomperts review the key role of Wnt signaling in all aspects of lung development, repair, and disease progression. They provide an overview of recent research findings and highlight where research is needed to further elucidate mechanisms of action, with the aim of improving disease treatments.

Introduction

The lung is a structurally and functionally intricate organ, with over 40 different, known cell types1. The advent of single-cell sequencing and other technologies continues to increase this number and contributes to the striking complexity of the lung. At its most proximal portion, the cartilaginous conducting airways harbor a pseudostratified mucociliary epithelium that plays a vital role in host defense. Inhaled harmful particles, pathogenic organisms, and debris are expectorated from the airways via a process known as mucociliary clearance (MCC). Inhaled contents are first entrapped by a layer of mucus, produced by goblet cells, that are then transported proximally by the unidirectional beating of cilia from terminal bronchioles to the trachea2. The coordinated removal of debris by ciliated cells and mucus-producing goblet cells is facilitated by lubrication from a periciliary water layer. The concerted undertaken by these multiple cell types together comprise the mucociliary escalator2. The bronchioles, also referred to as the conducting airways, are additionally important for moving gases to and from the distal lung, which contain the alveolar sacs necessary for gas exchange. Atmospheric oxygen undergoes exchange for blood carbon dioxide, a process that promotes cellular respiration for all tissues of the body.

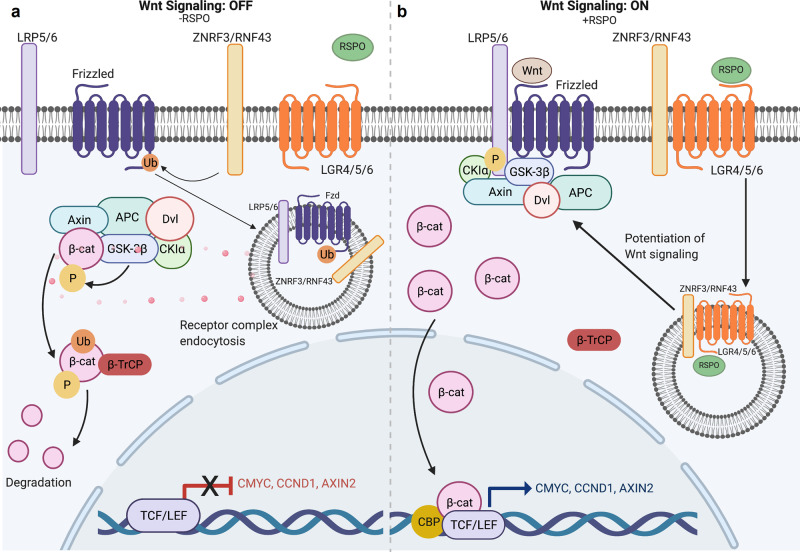

The wingless related-integration site (Wnt)/β-catenin signaling pathway plays an instrumental role in stem cell self-renewal across several tissue epithelia3. R-spondin ligands are cysteine-rich glycoproteins that bind to their cognate leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein coupled receptor (LGR) LGR4/5/6 receptors and E3 ubiquitin ligases ring finger protein (RNF)43/ZNRF3 via their furin-like domains4,5. In the absence of R-spondins, RNF43/ZNR43 ubiquitinate the Frizzled receptors that targets them for degradation (Fig. 1a, b). As such, Wnt signaling is dampened. Under canonical conditions in the absence of Wnt ligand, β-catenin is in complex with several other proteins including Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), Glycogen synthase kinase-3a, Glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK3β), casein kinase I (CKI), Axin, and Disheveled, among others (Fig. 1a)3. These proteins together comprise a destruction complex. CKIγ first phosphorylates β-catenin at residue serine 45, a priming event that allows for recognition by GSK3β, which phosphorylates β-catenin at serine 33, serine 37, and threonine 413. These N-terminal post-translational modifications mark β-catenin for ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation by the E3 ubiquitin ligase β-transducin repeat-containing protein (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1. Overview of canonical Wnt signaling.

a In the absence of RSPO binding to LGR4/5/6, ubiquitin ligase ZNRF43/RNF43 ubiquitinates the Frizzled receptor which leads to receptor complex endocytosis, β-catenin degradation and subsequent inhibition of Wnt-driven transcriptional activity5. b The binding of RSPO to LGR4/5/6 potentiates Wnt signaling by removing ZNR43/RNF43 ubiquitin ligase from the cell membrane, which would otherwise mark Frizzled receptor for ubiquitination. Frizzled receptors are then able to interact with both Wnt ligand and LRP5/6 co-receptor to drive Wnt signaling cascade. β-catenin then escapes cytoplasmic proteasomal degradation, resulting in its nuclear translocation, interactions with transcription factors. TCF/LEF, and subsequent transactivation of Wnt target genes like c-MYC, CyclinD1, and Axin25.

However, upon Wnt transcription and translation, the ligand enters to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and encounters Porcupine, an ER-resident protein that palmitoylates N-terminal cysteine residues of Wnt proteins. This lipid tail modification has been shown to be necessary for Wnt ligand secretion6,7. Wnt ligand then binds to LRP5/6 and appropriate Frizzled co-receptor on the same or neighboring cell. Moreover, R-spondins can potentiate and amplify Wnt signaling by forming complexes with their cognate LGR pair and binding to RNF43/ZNR43 to prevent Frizzled receptor ubiquitination. Together, these events allow for a cascade of molecular events that results in disassembly of the cytoplasmic destruction complex (Fig. 1b). β-catenin then accumulates in the cytoplasm, subsequently translocates to the nucleus, and interacts with transcription factors T-cell factor/Lymphoid enhancer factor 1 (TCF/LEF) (Fig. 1b). In this way, β-catenin drives transactivation of downstream target genes such as c-MYC, AXIN2, and CYCLIN D1 among others (Fig. 1b). The canonical Wnt signaling described above is important in a variety of cellular processes including proliferation, self-renewal, epithelial to mesenchymal transitions, and migration and motility.

In contrast, non-canonical Wnt signaling is often thought of as the β-catenin-independent pathway. One arm of this pathway regulates planar cell polarity (PCP), during which Frizzled receptors trigger downstream activation of RhoA and Rac GTPases that promote cytoskeletal remodeling8. A second arm of non-canonical Wnt signaling lies in Wnt-Frizzled binding that triggers Phospholipase C and downstream Ca2+ activity for regulation of cell migration and fate decisions8. It is important to note that Porcupine palmitoylates all 19 mammalian Wnt ligands and is therefore necessary for their secretion, including those that partake in non-canonical signaling.

Over the past several years, much research has been put forth toward carefully dissecting the nuanced role of Wnt signaling across several disciplines pertaining to lung biology. This review aims to highlight the major contributions made to our current understanding of the Wnt signaling pathway in lung and airway development, its role in proximal and distal airway homeostasis and relevant niche biology, as well as its role in directed differentiation efforts of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and embryonic stem cells (ESCs) to the lung lineage, in organoid culture models, and its perturbations in disease states.

Development

Detailed staging and mechanisms of both human and murine lung development have been well reviewed by others9–12. To briefly summarize murine lung development, during the embryonic stage, the ventral anterior foregut endoderm (AFE) expresses the transcription factor Nkx2.1 at mouse embryonic day (E) 9.0 as a sign of the specification to promote initial lung budding. From E9.5–E12.5, two lung buds with high Nkx2.1 expression and a proximal portion with low Nkx2.1 that later forms the trachea emerge concomitantly with tracheo-esophageal septation. From E12.5–E16.5 during the pseudoglandular stage, the lung buds undergo a period of branching morphogenesis to form the lung tree and terminal bronchioles. Upon completion of the canalicular and saccular stages of development (E16.5-Postnatal (P) day 4), the terminal bronchioles narrow and begin to form epithelial sacs. These structures later form fully mature alveolar structures for gas exchange by P21 during the alveolarization phase9. In contrast, alveolarization begins pre-partum during human lung development and continues postnatally into childhood13.

Coordinated development of the conducting and distal airways is a vital process during which both the epithelial and mesenchymal compartments play integral roles. The developing lung endodermal buds penetrate the splanchnic mesoderm and mesothelium around E9.5. The developing distal lung then acquires four distinct layers, each with its own unique anatomical, cellular, morphologic, and molecular profiles: endoderm (epithelium), subepithelial mesoderm (mesenchyme), submesothelial mesoderm (mesenchyme), and mesothelium. Transient amplifying submesothelial cells give rise to a parabronchial smooth muscle cell (PSMC) progenitor population. This cell population then migrates more proximally around the bronchi and differentiates into smooth muscle cells (SMCs)14,15. Studies assessing the expression levels of various Wnt/β-catenin signaling members and activity reporters in these aforementioned compartments during lung development have identified contrasting findings16,17. However, a myriad of studies collectively demonstrates that the developing lung mesenchyme displays several highly regulated interactions with the lung endoderm in both mouse and human that together coordinate normal lung organogenesis9, many of which are Wnt-mediated.

Embryonic stage (E9.5–E12.5)

Wnt signaling plays a role in some of the earliest stages of cardiopulmonary specification. Wnt2+ Gli1+ Isl1+ cells comprise the multipotent cardiopulmonary mesoderm progenitors (CPPs) that orchestrate heart and lung development. Lineage tracing of Wnt2+ CPPs at E8.5 demonstrates their capacity to generate the cardiac inflow tract and pulmonary mesoderm cell lineage by E17.518. These cells are important for the vital epithelial–mesenchymal interactions that occur during lung development.

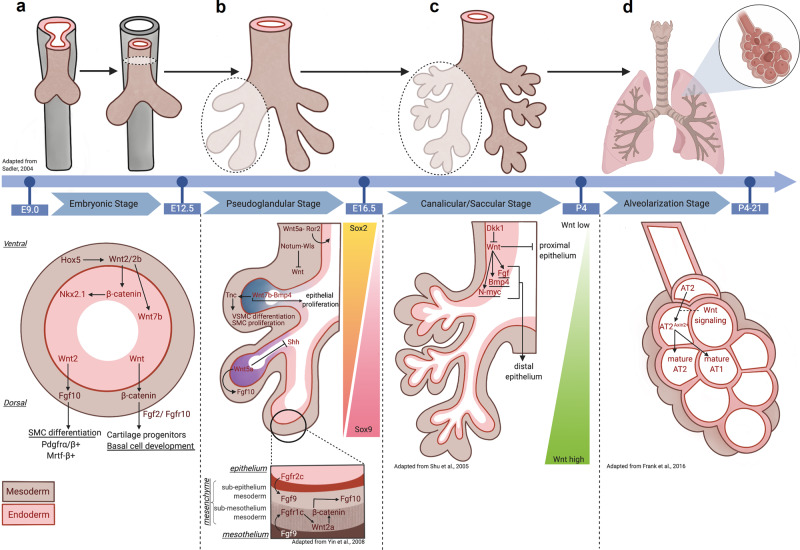

Crosstalk from developing mesenchyme to endoderm

Wnt-driven mesenchymal-to-endodermal crosstalk is critically important from the earliest stages of lung development. From E9.5–12.5, there is active Wnt/β-catenin signaling in both the epithelium and the mesenchyme adjacent to the future proximal airway as measured by TOPGAL and AXIN2-LacZ Wnt activity reporters19,20. Canonical Wnt2/2b ligands are spatiotemporally regulated by Hox5 genes during this stage, with notable mesodermal expression near the ventral aspect of the anterior foregut between E9.0 and E10.521 (Fig. 2a). Together, Wnt2/2b cooperate to promote Nkx2.1+ lung endodermal specification (Fig. 2a), as mice without them display lung agenesis22–24. Wnt2/2b converges on canonical signaling in the developing endoderm, as deletion of β-catenin in the anterior foregut also display lung agenesis, resulting in the upregulation of a Sox2+ digestive progenitor identity19,22. In contrast, constitutive activation of β-catenin prevents tracheo-esophageal septation and instead drives Nkx2.1+ lung endodermal progenitor expansion19,22.

Fig. 2. Wnt signals mediate epithelial–mesenchymal interactions during lung development.

a During the embryonic stage (E9.0–12.5) of development, lung bud emerges from tracheal-esophageal septation occurs9. Mesenchymal (brown) HOX5 spatiotemporally regulates endodermal (pink) Wnt2/2b to establish NKX2.1 lung progenitor via downstream β-catenin signaling21–24. Endodermal Wnt ligands also promote mesenchymal FGF10 and β-catenin, which then allow for SMC differentiation and cartilage and basal cell development27. b During the pseudoglandular stage (E12.5–E16.5), lung buds undergo branching morphogenesis to develop terminal bronchioles9. Mesenchymal Wnt5a promotes tracheal and cartilage formation via ROR2-dependent mechanisms33. Wntless (Wls)-regulated Notum suppresses mesenchymal Wnt and is necessary for tracheal development and branching morphogenesis39,40. A Wnt7b-BMP4 signaling axis also promotes epithelial proliferation and mesenchymal vascular SMC (VSMC) differentiation and SMC proliferation35–38. Further, epithelial Wnt5a expression is highest in distal tips31,33 and works to promote branching morphogenesis via suppression and activation of SHH and Fgf10 signaling, respectively34. A closer examination of the mesenchyme reveals FGF9 signaling from both the epithelium and mesothelium converge to promote submesothelial Wnt2a and facilitate mesenchymal cell proliferation14. c During the canalicular/saccular stages of development (E16.5-P4), terminal bronchioles become more defined and form epithelial sacs9. Negative regulation of Wnt by DKK1 results in proximalization of lung epithelium. High levels of Wnt signaling drive a distal airway phenotype, mediated in part by N-MYC-BMP4-FGF signaling44. d The alveolarization stage (P4–21) concludes with the maturation of alveolar structures13. Wnt-responsive (AXIN2+) ATII cells regulate lung alveologenesis by skewing toward a mature ATII lineage and in lieu of an ATI lineage47.

The developing embryonic lung also has measures in place to curb canonical Wnt signaling. While homeobox protein 1 (Barx1) is prominently expressed in the developing stomach mesenchyme where it orchestrates endodermal differentiation, its expression throughout the dorsal foregut mesenchyme and mainstem bronchi has been shown to inhibit endodermal Wnt signaling to promote thoracic foregut specification25. Similar to constitutive β-catenin activation, deletion of Barx1 results in the loss of tracheo-esophageal septation as evidenced by single, contiguous luminal layer of Nkx2.1+ tracheal and Sox2+ esophageal epithelium by E10.519,22,25.

Crosstalk from developing endoderm to mesenchyme

As early as E11.5, canonical Wnt2 ligand signaling promotes fibroblast growth factor 10 (Fgf10) signaling that, in turn, facilitates differentiation of immature platelet-derived growth factor receptor (Pdgfr)α/β+ smooth muscle cells by regulating the expression of myocardin and Mrtf-B, critical transcription factors in myogenesis26 (Fig. 2a). Mesenchymal Wnt2 also promotes endodermal Wnt7b expression that later signals back to the subepithelial mesenchyme to further drive SMC differentiation26. More recently, epithelial Wnt ligands were shown to activate mesenchymal β-catenin, which alongside Fgf10/Fgfr2, regulate both cartilage progenitors and basal cell development27 (Fig. 2a).

Pseudoglandular stage (E12.5–E16.5)

Constitutive activation of β-catenin in surfactant protein C (Sftpc)+ cells drives distal conducting airway dilatation concomitant with no differentiation to either the secretory or ciliated cell fate28. Consistent with this, R-spondin 2 (Rspo2) facilitates normal embryonic lung growth and the start of branching morphogenesis by potentiating Wnt/β-catenin signaling29. A recent study identified, however, that Rspo2 antagonizes RNF43 and zinc and ring finger (ZNRF)3 to regulate limb and lung formation in xenopus4. These efforts resulted in a paradigm shift, demonstrating that Rspo2 can potentiate Wnt signaling in the absence of LGR4,30. Interestingly, while Rspo2 drives branching morphogenesis earlier in development, it has no role in the differentiation of epithelial or mesenchymal cell types29. This suggests functional redundancy in the varying upstream regulators of Wnt signaling in embryonic lung development.

Several Wnt ligands have been well characterized in the pseudoglandular stage. Wnt5a is diffusely expressed in both the epithelium and mesenchyme as early as E12.031 (Fig. 2b). Its expression is dynamic and highest in the distal epithelium at branching point tips at E16.0 and is critical for tracheal elongation, cartilage ring patterning, and constraining distal airway expansion31–33. Furthermore, epithelial Wnt5a regulates distal lung morphogenesis via suppression and activation of sonic hedgehog (Shh) and Fgf10 signaling, respectively34. Mesenchymal Wnt5a is primarily responsible for tracheal elongation and cartilage ring formation via Ror2-dependent mechanisms in the dorsal tracheal mesenchyme33.

Wnt2a is expressed in the distal lung submesothelial layer during branching morphogenesis20. Epithelial- or mesothelial-derived FGF9 triggers activation of mesenchymal FGFR1/2 at E13.514. Fgfr1/2 then activates submesothelial Wnt2a to converge on β-catenin signaling that, in turn, promotes mesenchymal cell proliferation that is important for organ growth14 (Fig. 2b). Mesodermal β-catenin additionally promotes Fgf10+ PSMC progenitor amplification but plays no role in their differentiation to SMCs. However, proper endothelial cell differentiation is contingent on β-catenin signaling, indicating its necessity for the formation of multiple mesenchymal lineages via paired-like homeodomain transcription factor 2 (PITX2)-dependent mechanisms15.

Wnt7b is expressed throughout the airway epithelium by the start of the pseudoglandular stage, with the greatest expression localized to the distal airway, specifically the lung bud tips35,36 (Fig. 2b). Wnt7b loss-of-function mice retain proximodistal patterning despite their smaller lung architecture and incomplete cartilaginous ring formation35,37. Furthermore, autocrine Wnt7b signaling governs epithelial proliferation, in part, by Bmp4-dependent mechanisms37.

Epithelial Wnt signals delivered to the overlying mesenchyme also play an instrumental role in this stage of lung development. Endodermal-derived Wnt7b promotes lung mesenchymal proliferation and pulmonary vasculature growth in this stage35,37 (Fig. 2b), as its inactivation results in mouse lung hypoplasia, weakened vascular smooth muscle integrity, and death within minutes postnatally due to respiratory failure35. Wnt7b also provides a paracrine signal to the adjacent mesenchyme to promote Pdgfrβ+ pulmonary SMC proliferation and commitment to vascular SMCs38, which is mediated by extracellular matrix protein tenascin C38 (Fig. 2b).

As with the embryonic phase, tight regulation of canonical Wnt signaling activity is also important in the pseudoglandular stage. Notum, a deacylase that removes Wnt lipid modifications and therefore inhibits Wnt secretion, is critical for tracheal development39. Notum knockout mice exhibit tracheal stenosis, reduction in cartilaginous rings, and trachealis muscle by E16.539. Notum is regulated by Wntless (Wls), a cargo protein involved in trafficking lipid-modified Wnt from the Golgi to the cell surface. Epithelial deletion of Wls also impairs tracheal development, branching morphogenesis, and proximo-distal patterning as early as E12.539,40. Further, in cultured lung explants, canonical Wnt signaling inhibitor dickkopf1 (Dkk1) inhibits lung tree branching and mesenchymal differentiation by decreasing distal mesenchymal Wnt2a, Pdgfrα, fibronectin, and alpha-smooth muscle actin expression20.

Inhibition of canonical Wnt signaling in the pseudoglandular stage is also achieved by activation of non-canonical Wnt signaling. Epithelial expression of the Cadherin EGF LAG seven-pass G-type receptor 1 (Celsr1) and PCP protein 2 (Vangl2) proteins involved with PCP axis promote branching morphogenesis, as mice with mutations in either of these proteins display misshapen lungs and fewer, more narrow airway lumens41. In addition, transcription factor Gata binding factor 6 (Gata6) activates non-canonical receptor Frizzled (Fzd2), which inhibits canonical Wnt signaling to constrain bronchioalveolar stem cell expansion during development42. The loss of Gata6 in Sftpc+ lung epithelium leads to dilated airways and neonatal death42.

Canalicular/saccular stages (E16.5-P4)

While dispensable for early proximo-distal patterning, canonical Wnt7b ligand promotes distal Aquaporin5+ ATI lung epithelial cell differentiation during the canalicular and saccular stages35. These findings stand in contrast to those found by another group identifying normal, preserved cell differentiation from Wnt7b−/− mouse lungs37. Others report that β-catenin in Sftpc-expressing lung endodermal progenitor cells is necessary for the formation of terminal alveolar saccules, as its loss results in a proximalized lung with enlarged bronchial tubes as early as E13.543,44. Ectopic Dkk1 expression phenocopies these findings, likely through activation of Fgf10-Fgfr2 signaling44. During this stage, β-catenin is sufficient but not necessary for Sftpc+ lung endodermal progenitor cell proliferation45. Constitutive activation of β-catenin decreases differentiation of distal pulmonary cell types and instead promotes ectopic expression of gut and intestinal cell lineages45. This is accomplished by β-catenin binding to the N-myc, Bmp4, and Fgf promoters44 (Fig. 2c).

Alveolarization stage (P4–P21)

Although studies have well characterized the mechanisms underpinning several early stages of lung development and the involvement of Wnt signaling, this remains poorly understood in the alveolarization stage. Early studies by Mucenski et al. demonstrate that a constitutively active form of β-catenin results in Forkhead boxa2 (Foxa2) inhibition, thereby contributing to epithelial cell dysplasia and goblet cell hyperplasia46. More recently, a study found a wave of Wnt signaling emerges in the late sacculation/early alveologenesis stage, marked by the expansion of Wnt-dependent AXIN2+ alveolar type II (ATII) cells that contribute to the budding alveolus47 (Fig. 2d). In contrast, low Wnt signaling skews the cellular fate toward an alveolar type I (ATI)-like lineage47. These results not only indicate the critical role of β-catenin, but also suggest that its tight spatiotemporal regulation is important for proper respiratory epithelial differentiation.

Prospective/discussion of Wnt signaling in lung development

While all of these studies have proven instrumental in allowing us to define the role of Wnt signaling throughout the varying stages of lung development, much remains to be learned. It is apparent that the phases of lung development are interdependent on each other, rendering it difficult to interpret the biology that is specifically responsible for a given phase in isolation from other phases of development. It is critical that we begin to further dissect the dynamic nature of niche interactions during distinct phases of development. As such, development of novel tools to achieve this level of granularity and isolation will yield more nuanced insight of not only Wnt signaling, but other signaling cascades, in lung developmental biology. In addition, the advent of in vitro organoid systems has and will continue to allow for us to better understand human airway and lung development specifically. At the molecular level, much remains to be understood about the dynamic receptor–ligand interactions. The seminal work of Szenker-Ravi et al. and Lebensohn et al. raises the question: how does Rspo2 mechanistically potentiate Wnt signaling in the absence of LGR receptors4,30? Under what circumstances is R-spondin interaction with its cognate LGR required for distinct phases of development?

Submucosal gland biology

Submucosal glands (SMGs) are tubuloacinar structures of the submucosal region of the airway that are contiguous with the surface airway epithelium (SAE) by connecting ducts and play a critical role in mucous secretions that facilitate MCC, a function that is vital for host defense. SMGs contain several cell types including myoepithelial cells (MECs), ciliated cells, secretory cells, and basal cells. It was recently observed that SMGs also harbor glandular progenitors and that these cell types act as a reserve stem cell population to facilitate proximal airway regeneration following severe injury48–51.

In humans, SMGs localize throughout the trachea and bronchi of the proximal airway. However, in diseases such as cystic fibrosis, SMGs have been reported to extend more distally into the bronchioles of humans in addition to being more hyperplastic and hypertrophic52. In contrast, mice have primitive SMGs that are restricted to only the most proximal tip of the trachea. As such, ferrets and pigs have recently emerged as a more tractable model system to study SMG biology, as their SMGs develop postnatally and localize throughout the proximal airway and are therefore more similar to what is observed in humans48,51.

Early studies in ferret airways offered insight into Lef1 localization at the invaginating tips of the SMG buds in early development53. Using human, ferret, and mouse model systems, Lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 (LEF1) was then shown to be necessary but not sufficient for SMG morphogenesis52 despite no reportedly appreciable changes in β-catenin nuclear localization54. Sox2 and Sox17 each function to suppress Wnt/β-catenin-mediated activation of the Lef1 promoter55–58, indicating that these signaling axes are key regulators of SMG morphogenesis.

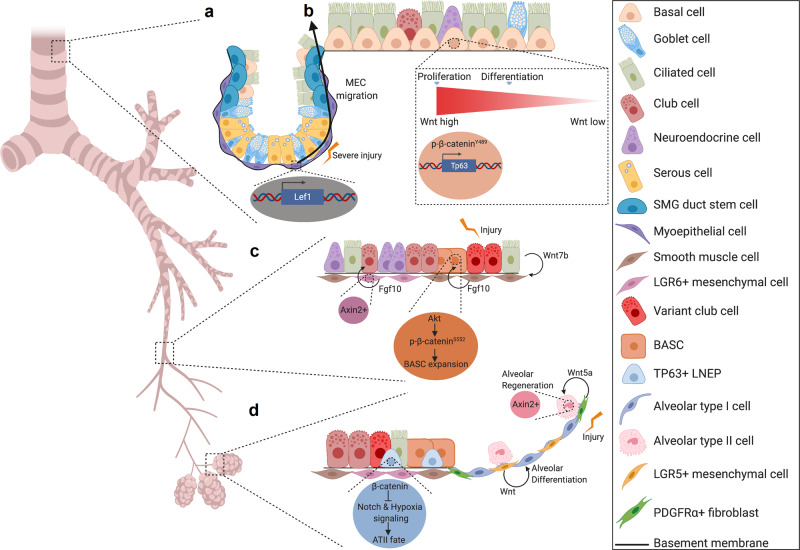

Wnt signaling is dynamically activated in SMGs following proximal airway injury concomitant with the proliferative phase of repair59. Further, Wnt3a is sufficient to promote glandular progenitor proliferation. Wnt-active cells reside near label-retaining cells of the SMG and were thought to be a regulatory component of the stem cell niche for repair59. This was later confirmed in a follow-up study that illustrated the capacity of MECs to migrate to the SAE and contribute to the repair process by giving rise to several differentiated cell types of the airway48,51. Further, Lef1 overexpression is sufficient to induce cell movement and migration programs that promotes MEC commitment to differentiated lineages of the proximal airway48 (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3. Wnt signaling plays pivotal roles in submucosal gland, proximal airway, bronchiolar, and distal lung regeneration.

a Following severe injury, Lef1 transcription within MECs of the SMGs promotes their migration to the surface airway epithelium and their subsequent ability to give rise to the differentiated cell types of the proximal airway48,51. b In the proximal airway ABSCs employ high levels of Wnt signaling to facilitate proliferation and medium levels of Wnt signaling to promote differentiation to the ciliated cell fate. At the molecular level, this appears to be accomplished by nuclear localization of p-β-cateninY489 65. Further, Tp63 is regulated by upstream Wnt signaling to promote basal cell stemness, thereby inhibiting differentiation to ciliated cells66. c In the bronchioles after injury, ciliated cells produce Wnt7b ligand that signals to airway smooth muscle cells (SMCs). SMCs then secrete Fgf10 ligand to promote an Akt/p-β-cateninS552 signaling cascade. These events then, in turn, promote BASC expansion76,77. Another study identified that Wnt-responsive (Axin2+) Lgr6+ mesenchymal cells are a key source of Fgf10 ligand to promote bronchiolar repair81. d At the bronchioalveolar duct junction, LNEPs employ β-catenin signaling to inhibit Notch and hypoxia signaling that is permissive for formation of an ATII-like cell fate80. Further, Lgr5+ mesenchymal cells secrete Wnt ligands that promote alveolar differentiation81. In the alveolus, Pdgfrα+ fibroblasts are also a key source of Wnt5a to signal to Axin2+ ATII cells to drive alveolar regeneration83.

Proximal airway homeostasis and regeneration

The proximal airway harbors a pseudostratified epithelium that is comprised of basal cells, mucus-secreting goblet and secretory (club) cells, and ciliated cells. Under the majority of circumstances, the basal cell is the resident adult stem cell responsible for giving rise to differentiated progeny. However, because the trachea of mice has a slow turnover rate of approximately one cell every 7–11 days, injury repair models are often employed to understand the cellular dynamics of stem cell fate decisions60.

The development of an understanding for how Wnt signaling modulates proximal airway homeostasis and regeneration remains in its infancy. It is known that basal cell β-catenin signaling is dynamically activated and necessary for the proliferative phase in murine injury repair models59,61–63. In addition, as described above, Wnt signals facilitate MEC contribution to proximal airway regeneration following severe injury48. At the cellular level, a recent group identified that a subset of Pdgfrα+ cells in the intercartilaginous zone are transiently, dynamically activated to secrete Wnt ligand that signals to the airway epithelium to promote its proliferation64. During differentiation, β-catenin activity is increased in air–liquid interface (ALI) cultures, a culturing system used to model airway epithelial remodeling, and enhances specification for the ciliated cell lineage61. In vivo, this phase is also driven by Wnt secretion from K5+ ABSCs that are necessary for differentiation to the ciliated cell fate64.

While Wnt signaling promotes ciliated cell differentiation, this is not true at all doses of pathway activation65. In contrast, high levels of Wnt signaling drive ABSC hyperproliferation concomitant with a phosphorylated form of nuclear β-catenin at Y489 (p-β-cateninY489) and abolishment of differentiation to the ciliated cell fate65 (Fig. 3b). Haas et al. demonstrated that high Wnt signaling triggers transcription of Tp63, which then acts as a master regulator of basal cell stemness66. A recently identified novel Wnt signaling inhibitor can promote restoration of Wnt-induced dysregulation of proximal airway homeostasis via p-β-cateninY489/TP63-related mechanisms65 (Fig. 3b), further implicating the importance of the pathway in proximal airway homeostasis.

Distal lung homeostasis and regeneration

As the trachea branches and forms the distal lung, there are appreciable changes in the cell types that act as stem or progenitor cells in homeostasis and regeneration that are spatially defined. In the mouse bronchiole, Scgb1a1+ Scgb3a2+ club cells, Scgb1a1− Upka3+ club cells, and Cgrp+ neuroendocrine cells can all act as stem/progenitor cells in either homeostatic or regenerative conditions67–69. The bronchoalveolar duct junction (BADJ) houses the Scgb1a1+ Sftpc+ Sca1+ bronchoalveolar stem cell (BASC)70,71. Further, Sftpc+ ATII cells in the alveolar region undergo self-renewal and give rise to ATI cells72. Most recently, a family of stem/progenitor cells referred to as the lineage-negative epithelial progenitors (LNEPs) have been characterized as quiescent at homeostasis but are mobilized under injurious conditions to regenerate the lungs73,74. Although the intricate complexity of the identity of these stem cell progenitors continues to be an area of current investigation, Wnt signaling plays critical roles in several of these regional compartments in regeneration.

From a cell biology perspective, several of the aforementioned identified progenitor populations or non-stem supporting niche cells employ Wnt signaling in bronchiolar, bronchioalveolar, or alveolar regeneration. Although an early study reported that β-catenin in club cells is dispensable for bronchiolar epithelial repair75, several subsequent findings indicate a highly important and intricately regulated role for this pathway at the cellular level in repair.

In the bronchioles and BADJ following naphthalene injury, ciliated cells induce Wnt7b expression that signals to the PSMCs to induce Fgf10 expression76,77 (Fig. 3c). Mesenchymal Fgf10 then induces Ak strain transforming (AKT)-mediated phosphorylation of β-catenin at S552 to promote BASC expansion and subsequent epithelial regeneration78 (Fig. 3c). Constitutive activation of β-catenin increases bronchiolar stem cell expansion and attenuates differentiation79. β-catenin stabilization also skews sex-determining region Y-box 2 (Sox2)+ LNEPs toward an ATII-like rather than K5+ cell fate by inhibiting Notch and hypoxia signaling following influenza infection80 (Fig. 3d). More recently, a study also identified that bronchiolar Lgr6+ mesenchyme is a Wnt-responsive cell population that secretes Fgf10 to signal to promote epithelial club cell differentiation81 (Fig. 3c).

In contrast, Wnt production from the alveolar Lgr5+ mesenchyme facilitates alveolar differentiation81 (Fig. 3d). A subset of Pdgfrα+ alveolar fibroblasts are Wnt-responsive (AXIN2+) signal to adjacent to ATII cells to promote their self-renewal and differentiation to ATI cells82. Interestingly, Pdgfrα+ alveolar fibroblasts also serve as key source of Wnt5a that signals to Axin2+ ATII cells to facilitate their self-renewal during homeostasis83, together suggesting the potential dual function of Wnt production and Wnt responsiveness of a single-cell (Fig. 3d). In the context of injury, however, ATII cells become Axin2+84 and induce autocrine Wnt signaling to promote progenitor expansion83. A recent study also demonstrated that neutrophil transmigration facilitates epithelial regeneration by inducing β-catenin signaling in neighboring ATII cells85.

At the molecular level, transcription factors and co-activators within the nucleus also play pivotal roles in modulation of bronchiolar and alveolar progenitor differentiation. In the bronchioles, interaction between β-catenin and P300 facilitates mucus cell formation86. Further, β-catenin interaction with either c-AMP element response binding protein or P300 inhibits generation of ciliated cells86. In the alveolus, a Wnt5a/Pyruvate kinase C signaling axis also activates the interaction between P300 and β-catenin, which is necessary for ATII differentiation to ATI cells87. Transcription factor Gata6 also prevents excessive BASC expansion by suppressing canonical Wnt signaling in response to injury42.

An important contribution to the field of whole lung regeneration was made in 2019 with the work of Mori et al., who employed conditional blastocyst complementation approaches in mice88. These injected cells compete for a specific niche to subsequently undergo the developmental program within the recipient host. Mori et al. identified that wild-type donor cells injected at the blastocyst stage of Ctnnb1 null mice were capable of giving rise to functionally mature lungs with mice living into adulthood. These efforts have collectively carved new strategies for whole lung regeneration in vivo.

Prospective/discussion of Wnt signaling in SMG biology, airway, and lung regeneration

The recent identification of a novel reserve stem cell population holds promising implications for disease therapeutics. However, much remains to be learned about the molecular and cellular cues that trigger MEC migration following severe injury. In addition, it will be important to dissect the functional and cellular heterogeneity of MECs in the SMGs and how they may or may not differentially contribute to airway regeneration and/or disease progression. Although it is clear that Wnt signaling plays a pivotal role in SMG morphogenesis and contributes to repair, closer analyses at single-cell resolution will further refine the granularity of our understanding of its biology.

While these initial findings are important for the field, much remains to be explored. In particular, we need to better dissect the spatiotemporal relationship between the diverse cell types of the airway as it relates to Wnt signaling. Previous work has illustrated the critical importance of mesenchymal-epithelial cell crosstalk for mediating airway regeneration64,89. As such, these efforts should be expanded to the realm of Wnt/β-catenin signaling given its appreciated importance. Specifically, these studies have elucidated the structural, cellular, and molecular complexity and heterogeneity of the intercartilaginous zone niche that warrants further investigation. Future studies should seek to further identify and characterize the cell types that comprise this niche, as they will inherently inform our understanding of the mechanisms governing proximal airway regeneration. Further, although the use of in vitro ALI culturing systems has allowed for significant biological understanding of Wnt signaling in airway biology, this platform has inherent limitations. Differences in culture media and timing of treatments have the possibility to yield seemingly conflicting and contradictory results. Last, the creation of transgenic mouse model tools that can uniquely isolate and dissect the role of this pathway in proliferation versus differentiation in vivo, two distinct but co-variate processes, would greatly advance not only the Wnt field forward, but the field of airway biology as a whole.

In vitro directed differentiation from iPSCs and ESCs and implementation in organoid models

Reliable, efficient differentiation of human PSCs and ESCs along airway and lung lineages has garnered the attention of several groups in recent years. These efforts have far-reaching implications for regenerative medicine, disease modeling, and forging opportunities for disease gene correction. These efforts gained prominence after Gouon-Evans et al. demonstrated the efficient enrichment of definitive endoderm from mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) via Activin A, a Nodal-like TGFβ family member known to induce an endodermal fate90. The use of Activin A has also been shown to drive definitive endoderm in human ESCs, mirroring developmental cascades observed in murine models91.

While the first reports of definitive endoderm derivation focused on midgut and posterior foregut endoderm specification90,91, the first report of lung-directed differentiation was described in 2011. Green et al. first illustrated accurate specification of FOXA2+ SOX2+ AFE via inhibition of BMP and TGFβ signaling in Activin A-induced definitive endoderm92 (Fig. 4a). Further differentiation of the AFE to NKX2.1+ lung endoderm progenitors was achieved through use of a WKFBE factor cocktail (WNT3a, KGF, FGF10, BMP4, EGF) alongside retinoic acid92 (Fig. 4a). Comparative analyses of mouse ESC- and iPSC-derived definitive endoderm have demonstrated that both display similar gene expression and global transcriptome profiles93,94.

Fig. 4. Directed differentiation of iPSCs to lung lineages utilizes perturbations in Wnt signaling at various stages.

a Primary report to lung-directed differentiation utilized Activin to induce definitive endoderm specification. Use of Noggin and SB431542, a bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) and transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) family signaling inhibitor, respectively, in Activin A-induced definitive endoderm drives anterior foregut endoderm (AFE) specification92. Further differentiation of the AFE would utilize a WKFBE factor cocktail (WNT3a, keratinocyte growth factor (KGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 10, BMP4, epidermal growth factor (EGF)) alongside retinoic acid (RA) to attain lung endoderm progenitors (NKX2.1+)92. Consistent with idea that activated Wnt signaling promotes distal lung phenotype, treatment of lung endoderm progenitors with Wnt3a, FGF10, and KGF promotes a distal phenotype92. b Subsequent studies introduced Wnt3a, alongside Activin, to generate definitive endoderm. GSK3β inhibitor CHIR, alongside FGFs and BMPs, facilitates generation of NKX2.1+ lung endoderm from anterior foregut endoderm. Tankyrase inhibition via treatment with IWR-1 skewed cells toward a more proximal fate95,99. New additions to differentiation protocols are indicated in blue while Wnt-specific biology is highlighted in green. c Subsequent efforts utilized among other factors in a “ventralization” cocktail that allowed for more efficient derivation of NKX2.1+ lung endoderm from anterior foregut endoderm96. New additions to differentiation protocols are indicated in blue while Wnt-specific biology is highlighted in green. d Between 2014–2017, refined strategies emerged that indicate the importance of the level of Wnt modulation by the absence or addition of CHIR to skew cell fates toward a more proximal or distal fate from NKX2.1+ lung endoderm98,100,101. New additions to differentiation protocols are indicated in blue while Wnt-specific biology is highlighted in green. e Most recently, using mouse PSCs, Wnt3a was removed from the generative of definitive endoderm and instead utilized in a “distalization media” to skew Nkx2.1+ lung endodermal progenitors to a more distal lung epithelial fate104–106. New additions to differentiation protocols are indicated in blue while Wnt-specific biology is highlighted in green.

Subsequent groups introduced modifications to the directed differentiation of iPSC/ESC described above. Mou et al. introduced a transient 1-day activation of canonical Wnt signaling in addition to the use of Activin A to generate definitive endoderm (Fig. 4b)95. Similar to prior reports, TGFβ inhibition was maintained to induce anteriorization (FOXA2+ SOX2+) of this lineage. Wnt activation via GSK3β inhibition was identified as necessary for BMP4-dependent generation of NKX2.1-expressing lung endoderm progenitors (Fig. 4b)90,91,95. These data are suggestive of a concise, tightly regulated gene expression patterning required to promote lung endodermal progenitor formation. Subsequent Wnt inhibition using tankyrase inhibitor IWR-1 alongside Bmp7/Fgf7/18 signaling perturbations skews the lineage toward a proximal airway phenotype, while Wnt activation favors distal phenotypes (Fig. 4b)95. While the study provided an avenue to proximal airway lineage formation, it did not indicate generation of functionally mature proximal and distal lung cell types.

To address this concern, Wong et al. optimized the stepwise differentiation of iPSCs-derived lung endoderm into proximal lineage-specific epithelial cells through dynamic additions of various growth factors targeting major developmental pathways including Wnt signaling96. Consistent with prior reports, Wnt3a alongside Activin A are important for the generation of definitive endoderm progenitors (CXCR4+ CKIT+) (Fig. 4c)95. Importantly, subsequent differentiation into AFE is a Wnt-independent process and instead dependent on FGF and SHH stimulation. Downstream proximal specification (K5+ P63+) additionally requires low BMP signaling96.

To contrast Fgf/Shh-mediated AFE induction (Fig. 4a), Huang et al. then demonstrated dual BMP/TGFB inhibition sequentially followed by Wnt/Tgfβ inhibition generates increased Nkx2.1+ AFE cells (Fig. 4c). Further, a “ventralization cocktail”, similar to that reported by Green et al., with the omission of EGF, comprised of GSK3β inhibitor CHIR99021 (hereafter, CHIR), Bmp4, Fgf10, KGF and RA together was used to induce the fraction of lung progenitors92,97 (Fig. 4c). Removal of Wnt agonist CHIR from the ventralization cocktail decreases the number of NKX2.1+ cells, highlighting its functionally necessary, non-redundant role in lung endoderm specification97,98 (Fig. 4c). Thus far, Wnt signaling has been implicated in definitive endoderm formation95,96,99, its inhibition for efficient AFE induction97,98, and its activation for lung endoderm formation95 (Fig. 4c).

Recapitulating the complex temporal and regional specificity of several signaling pathway activities in lung development has contributed to stunted progress in allowing for appropriate proximo-distal lung patterning from human PSCs. To address this, McCauley et al. generated NKX2.1+ lung epithelial progenitors from human PSCs using previously published, well-established protocols98,100,101. They later use cyclical Wnt signaling modulation via treatment with GSK3β inhibitor CHIR to preferentially skew distal lung patterning over proximal airway cell fates, similar to the patterning methodology described by Mou et al.95,101 (Fig. 4d).

Recent work has built on these efforts more recently by elucidating the minimum factors sufficient for functional ATII cell specification from lung endodermal progenitors, one of which is CHIR102. Interestingly, full ATII maturation necessitates transient Wnt signaling downregulation by removal and subsequent addback of CHIR102. These findings are consistent with prior work indicating a brief wave of low-level Wnt signaling in the latter stages of fetal distal lung development47. Most recently, Hurley et al. reported a more refined timeline indicating that CHIR removal from the media should be done for 4 days (starting day 17 of their protocol) and subsequently added back to promote cellular proliferation and subsequent generation of ATII cells103. In addition, the same group also utilized knowledge gained from Nkx2.1+ murine lung epithelial progenitors in vivo to efficiently generate proximalized or distalized airway epithelial cells104. Inspired by prior studies, Wnt3a was removed from the generation of the definitive endoderm and instead was included in a “distalization” media on sorted NKX2.1+ reporter cells104–106 (Fig. 4e).

All of these in vitro directed differentiation efforts have laid the groundwork for several follow-up foundational studies that have generated multi-ciliated cells107,108 and reproducible iPSC/PSC-derived lung organoids109–111. Dye et al. first described the use of these directed differentiation protocols to generate 3D organoid cultures110. More recently, Chen et al. further demonstrated their ability to undergo branching morphogenesis and proximo-distal specification112. Both groups were, however, consistent with their use of Wnt activation to promote ventralization of the AFE110,112. Several groups have additionally employed the use of human pluripotent stem cell-derived lung organoids, which uniquely contain both endoderm and mesodermal tissues, to model lung diseases such as pulmonary fibrosis and cystic fibrosis101,102,113 and to ultimately use them as a base for therapeutic drug screens114,115.

Prospective/discussion of Wnt signaling in iPSC differentiation

Through all stages of lung development, Wnt signaling, or its absence, plays a pivotal role in directing cellular differentiation. While Wnt signaling appears to be dispensable for definitive endoderm formation and is absent during anterior foregut patterning, its subsequent activation directs lung endoderm formation and distal lung specification. Many of these Wnt activation studies involve treatment with CHIR and it is important to note, however, that the effects of CHIR cannot be attributed only to Wnt signaling alone and may be perhaps due to Wnt/β-catenin-independent, GSK3β-dependent biology. Further, some studies have indicated variability in directed differentiation efficiencies between iPSC and ESC lines96,98,101. Taken together, these barriers in iPSC and ESC lung specification ultimately suggest a potential need for patient-specific differentiation protocols within the sphere of precision medicine in order to bypass cell–cell variability.

Disease pathogenesis

In light of its highly complex involvement across several normal biological processes, it follows that dysregulation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling cascade plays a similarly prevalent role in the pathogenesis of lung disease processes, including carcinogenesis, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) among others.

Lung cancer

Lung cancer kills more people than breast, colon, and prostate cancers combined, with an overall 5-year survival rate that remains 18%. Although mutations in the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway are common in malignancies in several tissue types, including colon and intestine, they remain rare in lung cancer116–119. However, early studies using β-catenin gain-of-function animals crossed with Nkx2.1 tissue-specific Cre recombinase mice developed tracheal and bronchial polyps that contain an undifferentiated epithelium that surrounds a mesenchymal core120, implicating a role for the pathway in carcinogenesis. Subsequently, a myriad of other studies has demonstrated its key role in lung tumor burden progression as well as chemoresistance, as described below.

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)

NSCLC is the most common histologically defined subtype of lung cancer, accounting for 85–90% of all lung cancers, and for which the most is known with respect to Wnt signaling. While activated Wnt/β-catenin signaling alone cannot drive tumorigenesis of the bronchiolar epithelium, its activation in the setting of KrasG12D mutations accelerates disease progression121. Further, KrasG12D;p53fl/fl;Prkci (KPI) lung adenocarcinoma (LADC) mouse model tumors arise from Tm4sf1 + Axin2+ ATII cells whereas KrasG12D;p53fl/fl (KP) tumors arise from BASCs122. In addition, KPI tumors are reliant on higher levels of Wnt/β-catenin signaling for their expansion, a signature that is also reflected in human patient tumors122.

NSCLC tumors with constitutively active β-catenin induce a more distal embryonic lung phenotype that also represses E-cadherin, consistent with a role for Wnt/β-catenin signaling in EMT-like phenotypic processes that may facilitate metastasis to distant sites62,121. Indeed, a subset of LADCs uniquely display Wnt target gene transcriptional profiles that are associated with and drive metastatic potential to brain and bone123. Specifically, TCF1, TCF4, LEF1, and HOXB9 are key transcription factors that mediate cancer cell metastatic behavior123.

While many efforts have mechanistically dissected the molecular biology of Wnt signaling within the Wnt-responsive cancer cells, it is also important to recognize the source of Wnt ligand that triggers these downstream signaling and cellular events. Recent work has identified the presence of Wnt-producing (Porcupine+) epithelial cells that are closely apposed to Wnt-responding (LGR5+) epithelial cells in LADC124. Human premalignant lesions and squamous lung cancer samples also display increased stromal and epithelial Porcupine as well as nuclear p-β-cateninY489 65, further elucidating the Wnt signaling niche networks that are targetable with small molecule inhibitors.

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC)

SCLC is a rare, yet aggressive disease characterized by tumors with neuroendocrine features, expressing markers such as Chromogranin A, Synaptophysin, UCHL1, ASCL1, and NEUROD1. Although initially responsive to chemotherapy, resistant disease rapidly emerges, accounting for its high mortality rate. Tracheal and bronchial polyps with constitutive activation of β-catenin contain higher levels of neuroendocrine marker Uchl1120. The Wnt pathway is also implicated in the biology underpinning chemoresistance, as negative regulators of the pathway, APC and CHD8, were mutated in one-third of relapsed patients relative to their primary lesion samples prior to chemotherapy treatment125. In vitro APC knockdown studies conferred activated Wnt signaling and subsequent chemoresistance in SCLC cell lines125. Future studies in both NSCLC and SCLC should investigate the cellular heterogeneity of the transcriptional profiles of Wnt production and responsiveness in the context of chemoresistance biology.

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)

IPF is a rare, progressive disease marked by chronic lung scarring that results in poor lung function and for which there is currently no therapy to halt or reverse the fibrosis. The role of Wnt signaling in IPF remains convoluted, although studies have observed nuclear β-catenin in bronchiolar lesions, alveolar structures, and fibrotic foci126, specifically p-β-cateninY489 127. Subsequent studies further elucidated a pathogenic role of the pathway in the disease process that is associated with poor prognosis128. Specifically, Wnt/β-catenin signaling is activated in humans with IPF and mouse models of the disease in both the mesenchyme as well as epithelium129–132. Further, administration of various Wnt signaling inhibitors attenuates the fibrotic phenotype both in vitro and in vivo129,130,133.

Wnt target gene Wnt-inducible signaling protein 1 is responsible, in part, for the fibrotic phenotype and decreased survival observed in animal models129. Further, LRP5 promotes β-catenin driven fibrosis by, in part, increasing TGFβ abundance128. LRP5 also acts to regulate the differentiation of alveolar macrophages and promote persistence of fibrosis134. In addition, the TGFβ pathway activates canonical Wnt signaling in human fibroblasts130 as well as induces extracellular vesicle secretion and subsequent release of Wnt5a ligand135. Together, these events trigger fibroblast proliferation and the fibrotic response. These findings also suggest multiple nodes of crosstalk between Wnt and TGFβ signaling cascades in IPF that warrants further investigation.

At the single-cell level, Wnt-producing cells are distinct from Wnt-responsive cells in humans with IPF136, suggesting the presence of an intricate epithelial-mesenchymal niche that parallels work identifying its functionality in normal injury repair of the distal lung83. Once internalized, the Wnt-responsive ATII cell secretes IL1β, which may then act as a profibrotic cytokine137.

In contrast, some have purported a protective role for β-catenin in the alveolar epithelium in bleomycin mouse models of fibrosis by promoting wound healing138. Taken together, these findings suggest complex, multi-faceted roles for Wnt/β-catenin signaling in IPF prevention, pathogenesis, persistence, and resolution.

Other lung diseases

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) is a rare pediatric lung disease characterized by abnormal distal lung development, declined lung function, increased inflammation, and increased fibrosis. BPD is often seen in premature infants or neonates that have received mechanical ventilation. In vitro and in vivo models of BPD employing hyperoxia injuries demonstrate reliance on mesenchymal Wnt5a on disease phenotypes139. BPD also shares a common downstream activated, phosphorylated form of β-catenin at Y489 that is also observed in IPF127,140, though much remains to be explored in this disease context. COPD also displays perturbed non-canonical Wnt signaling biology, as pulmonary fibroblasts secrete Wnt5a to inhibit alveolar canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling, thereby preventing epithelial repair141. Recent work has also begun to think about the role of Wnt signaling in the context of aging as well. Lehmann et al. reported that aged ATII cells exhibit increase senescence that is driven by activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling and is associated with profibrotic changes142.

Prospective/discussion of Wnt signaling in disease biology

The work of Nabhan et al. has paved the way for understanding the role of single-cell niches within distal lung regeneration83. The success of this lies, in part, because its generated understanding of the Wnt-producing (Wnt-expressing, Porcupine-positive) cells and the Wnt-responsive (Axin2+) cells via single-cell sequencing studies. This approach should be adopted in the context of disease processes, as it could hold particular promise with disease processes with known intermediates such as the malignant transformation underpinning lung squamous cell carcinoma. There also exists a plethora of outstanding questions largely underexplored within the sphere of aging. For example, how do stem cell niches throughout the airway and lung change with aging, both at the cellular and molecular levels? And how, if at all, do the alterations in Wnt signaling that occur in aging relate to distinct pathophysiology of disease processes?

Summary

Taken together, it is clear that Wnt signaling plays a major role in lung development, lung repair and regeneration, and the progression of many lung diseases. The rapid technological advances in the fields of molecular and cellular biology are greatly facilitating the study of Wnt signaling in lung biology. Advancing our knowledge on the exact mechanisms of Wnt signaling in the lung will allow for the development of more Wnt pathway targeted therapies that will hopefully lead to a therapeutic benefit for patients with lung diseases.

Author contributions

C.J.A., C.J.P.: manuscript writing, figure design and execution. B.N.G.: manuscript writing, figure design and execution, financial support.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cardoso WV, Whitsett JA. Resident cellular components of the lung: developmental aspects. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2008;5:767–771. doi: 10.1513/pats.200803-026HR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bustamante-Marin, X. M. & Ostrowski, L. E. Cilia and mucociliary clearance. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol.9, a028241 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Nusse R, Clevers H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling, disease, and emerging therapeutic modalities. Cell. 2017;169:985–999. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szenker-Ravi E, et al. RSPO2 inhibition of RNF43 and ZNRF3 governs limb development independently of LGR4/5/6. Nature. 2018;557:564–569. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0118-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clevers H, Loh KM, Nusse R. Stem cell signaling. An integral program for tissue renewal and regeneration: Wnt signaling and stem cell control. Science. 2014;346:1248012. doi: 10.1126/science.1248012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrott JJ, Cash GM, Smith AP, Barrow JR, Murtaugh LC. Deletion of mouse Porcn blocks Wnt ligand secretion and reveals an ectodermal etiology of human focal dermal hypoplasia/Goltz syndrome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:12752–12757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006437108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biechele S, Cox BJ, Rossant J. Porcupine homolog is required for canonical Wnt signaling and gastrulation in mouse embryos. Dev. Biol. 2011;355:275–285. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomez-Orte E, Saenz-Narciso B, Moreno S, Cabello J. Multiple functions of the noncanonical Wnt pathway. Trends Genet. 2013;29:545–553. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herriges M, Morrisey EE. Lung development: orchestrating the generation and regeneration of a complex organ. Development. 2014;141:502–513. doi: 10.1242/dev.098186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrisey EE, Hogan BL. Preparing for the first breath: genetic and cellular mechanisms in lung development. Dev. Cell. 2010;18:8–23. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schittny JC. Development of the lung. Cell Tissue Res. 2017;367:427–444. doi: 10.1007/s00441-016-2545-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nikolic, M. Z., Sun, D. & Rawlins, E. L. Human lung development: recent progress and new challenges. Development145, dev163485 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Warburton D, et al. Lung organogenesis. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2010;90:73–158. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(10)90003-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yin Y, et al. An FGF-WNT gene regulatory network controls lung mesenchyme development. Dev. Biol. 2008;319:426–436. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Langhe SP, et al. Formation and differentiation of multiple mesenchymal lineages during lung development is regulated by beta-catenin signaling. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1516. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al Alam D, et al. Contrasting expression of canonical Wnt signaling reporters TOPGAL, BATGAL and Axin2(LacZ) during murine lung development and repair. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e23139. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tebar M, Destree O, de Vree WJ, Ten Have-Opbroek AA. Expression of Tcf/Lef and sFrp and localization of beta-catenin in the developing mouse lung. Mech. Dev. 2001;109:437–440. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4773(01)00556-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peng T, et al. Coordination of heart and lung co-development by a multipotent cardiopulmonary progenitor. Nature. 2013;500:589–592. doi: 10.1038/nature12358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris-Johnson KS, Domyan ET, Vezina CM, Sun X. beta-Catenin promotes respiratory progenitor identity in mouse foregut. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:16287–16292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902274106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Langhe SP, et al. Dickkopf-1 (DKK1) reveals that fibronectin is a major target of Wnt signaling in branching morphogenesis of the mouse embryonic lung. Dev. Biol. 2005;277:316–331. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hrycaj SM, et al. Hox5 genes regulate the Wnt2/2b-Bmp4-signaling axis during lung development. Cell Rep. 2015;12:903–912. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goss AM, et al. Wnt2/2b and beta-catenin signaling are necessary and sufficient to specify lung progenitors in the foregut. Dev. Cell. 2009;17:290–298. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poulain M, Ober EA. Interplay between Wnt2 and Wnt2bb controls multiple steps of early foregut-derived organ development. Development. 2011;138:3557–3568. doi: 10.1242/dev.055921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rankin SA, Gallas AL, Neto A, Gomez-Skarmeta JL, Zorn AM. Suppression of Bmp4 signaling by the zinc-finger repressors Osr1 and Osr2 is required for Wnt/beta-catenin-mediated lung specification in Xenopus. Development. 2012;139:3010–3020. doi: 10.1242/dev.078220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woo J, Miletich I, Kim BM, Sharpe PT, Shivdasani RA. Barx1-mediated inhibition of Wnt signaling in the mouse thoracic foregut controls tracheo-esophageal septation and epithelial differentiation. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e22493. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goss AM, et al. Wnt2 signaling is necessary and sufficient to activate the airway smooth muscle program in the lung by regulating myocardin/Mrtf-B and Fgf10 expression. Dev. Biol. 2011;356:541–552. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hou, Z. et al. Wnt/Fgf crosstalk is required for the specification of basal cells in the mouse trachea. Development146, dev171496 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Hashimoto S, et al. beta-Catenin-SOX2 signaling regulates the fate of developing airway epithelium. J. Cell Sci. 2012;125:932–942. doi: 10.1242/jcs.092734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bell SM, et al. R-spondin 2 is required for normal laryngeal-tracheal, lung and limb morphogenesis. Development. 2008;135:1049–1058. doi: 10.1242/dev.013359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lebensohn, A. M. & Rohatgi, R. R-spondins can potentiate WNT signaling without LGRs. Elife7 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Li C, Xiao J, Hormi K, Borok Z, Minoo P. Wnt5a participates in distal lung morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 2002;248:68–81. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamaguchi TP, Bradley A, McMahon AP, Jones S. A Wnt5a pathway underlies outgrowth of multiple structures in the vertebrate embryo. Development. 1999;126:1211–1223. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.6.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kishimoto K, et al. Synchronized mesenchymal cell polarization and differentiation shape the formation of the murine trachea and esophagus. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:2816. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05189-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li C, et al. Wnt5a regulates Shh and Fgf10 signaling during lung development. Dev. Biol. 2005;287:86–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shu W, Jiang YQ, Lu MM, Morrisey EE. Wnt7b regulates mesenchymal proliferation and vascular development in the lung. Development. 2002;129:4831–4842. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.20.4831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weidenfeld J, Shu W, Zhang L, Millar SE, Morrisey EE. The WNT7b promoter is regulated by TTF-1, GATA6, and Foxa2 in lung epithelium. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:21061–21070. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111702200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rajagopal J, et al. Wnt7b stimulates embryonic lung growth by coordinately increasing the replication of epithelium and mesenchyme. Development. 2008;135:1625–1634. doi: 10.1242/dev.015495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen ED, et al. Wnt signaling regulates smooth muscle precursor development in the mouse lung via a tenascin C/PDGFR pathway. J. Clin. Investig. 2009;119:2538–2549. doi: 10.1172/JCI38079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gerhardt B, et al. Notum attenuates Wnt/beta-catenin signaling to promote tracheal cartilage patterning. Dev. Biol. 2018;436:14–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cornett B, et al. Wntless is required for peripheral lung differentiation and pulmonary vascular development. Dev. Biol. 2013;379:38–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yates LL, et al. The PCP genes Celsr1 and Vangl2 are required for normal lung branching morphogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010;19:2251–2267. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Y, et al. A Gata6-Wnt pathway required for epithelial stem cell development and airway regeneration. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:862–870. doi: 10.1038/ng.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mucenski ML, et al. beta-Catenin is required for specification of proximal/distal cell fate during lung morphogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:40231–40238. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305892200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shu W, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling acts upstream of N-myc, BMP4, and FGF signaling to regulate proximal-distal patterning in the lung. Dev. Biol. 2005;283:226–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okubo T, Hogan BL. Hyperactive Wnt signaling changes the developmental potential of embryonic lung endoderm. J. Biol. 2004;3:11. doi: 10.1186/jbiol3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mucenski ML, et al. Beta-catenin regulates differentiation of respiratory epithelial cells in vivo. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2005;289:L971–L979. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00172.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frank DB, et al. Emergence of a wave of Wnt signaling that regulates lung alveologenesis by controlling epithelial self-renewal and differentiation. Cell Rep. 2016;17:2312–2325. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lynch TJ, et al. Submucosal gland myoepithelial cells are reserve stem cells that can regenerate mouse tracheal epithelium. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;22:779. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Montoro DT, et al. A revised airway epithelial hierarchy includes CFTR-expressing ionocytes. Nature. 2018;560:319–324. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0393-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hegab AE, et al. Isolation and in vitro characterization of basal and submucosal gland duct stem/progenitor cells from human proximal airways. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2012;1:719–724. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2012-0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tata A, et al. Myoepithelial cells of submucosal glands can function as reserve stem cells to regenerate airways after injury. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;22:668–683.e666. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Duan D, et al. Submucosal gland development in the airway is controlled by lymphoid enhancer binding factor 1 (LEF1) Development. 1999;126:4441–4453. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.20.4441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Duan D, Sehgal A, Yao J, Engelhardt JF. Lef1 transcription factor expression defines airway progenitor cell targets for in utero gene therapy of submucosal gland in cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1998;18:750–758. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.18.6.2987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ritchie TC, et al. Developmental expression of catenins and associated proteins during submucosal gland morphogenesis in the airway. Exp. Lung Res. 2001;27:121–141. doi: 10.1080/019021401750069375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Driskell RR, et al. Wnt3a regulates Lef-1 expression during airway submucosal gland morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 2007;305:90–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Driskell RR, et al. Wnt-responsive element controls Lef-1 promoter expression during submucosal gland morphogenesis. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2004;287:L752–L763. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00026.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xie W, et al. Sox2 modulates Lef-1 expression during airway submucosal gland development. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2014;306:L645–L660. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00157.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu X, et al. Sox17 modulates Wnt3A/beta-catenin-mediated transcriptional activation of the Lef-1 promoter. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2010;299:L694–L710. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00140.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lynch TJ, et al. Wnt signaling regulates airway epithelial stem cells in adult murine submucosal glands. Stem Cells. 2016;34:2758–2771. doi: 10.1002/stem.2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rock JR, Randell SH, Hogan BL. Airway basal stem cells: a perspective on their roles in epithelial homeostasis and remodeling. Dis. Model Mech. 2010;3:545–556. doi: 10.1242/dmm.006031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brechbuhl HM, et al. beta-catenin dosage is a critical determinant of tracheal basal cell fate determination. Am. J. Pathol. 2011;179:367–379. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Giangreco A, et al. beta-Catenin determines upper airway progenitor cell fate and preinvasive squamous lung cancer progression by modulating epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J. Pathol. 2012;226:575–587. doi: 10.1002/path.3962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hsu HS, et al. Repair of naphthalene-induced acute tracheal injury by basal cells depends on beta-catenin. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2014;148:322–332. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aros CJ, et al. Distinct spatiotemporally dynamic Wnt-secreting niches regulate proximal airway regeneration and aging. Cell Stem Cell. 2020;27:413–429.e414. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2020.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aros CJ, et al. High-throughput drug screening identifies a potent wnt inhibitor that promotes airway basal stem cell homeostasis. Cell Rep. 2020;30:2055–2064.e2055. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.01.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Haas M, et al. DeltaN-Tp63 mediates Wnt/beta-catenin-induced inhibition of differentiation in basal stem cells of mucociliary epithelia. Cell Rep. 2019;28:3338–3352.e3336. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.08.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guha A, et al. Neuroepithelial body microenvironment is a niche for a distinct subset of Clara-like precursors in the developing airways. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:12592–12597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204710109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rawlins EL, et al. The role of Scgb1a1+ Clara cells in the long-term maintenance and repair of lung airway, but not alveolar, epithelium. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:525–534. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Guha A, Deshpande A, Jain A, Sebastiani P, Cardoso WV. Uroplakin 3a(+) cells are a distinctive population of epithelial progenitors that contribute to airway maintenance and post-injury repair. Cell Rep. 2017;19:246–254. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim CF, et al. Identification of bronchioalveolar stem cells in normal lung and lung cancer. Cell. 2005;121:823–835. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu Q, et al. Lung regeneration by multipotent stem cells residing at the bronchioalveolar-duct junction. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:728–738. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0346-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Barkauskas CE, et al. Type 2 alveolar cells are stem cells in adult lung. J. Clin. Investig. 2013;123:3025–3036. doi: 10.1172/JCI68782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vaughan AE, et al. Lineage-negative progenitors mobilize to regenerate lung epithelium after major injury. Nature. 2015;517:621–625. doi: 10.1038/nature14112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kathiriya, J. J., Brumwell, A. N., Jackson, J. R., Tang, X. & Chapman, H. A. Distinct airway epithelial stem cells hide among club cells but mobilize to promote alveolar regeneration. Cell Stem Cell (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Zemke AC, et al. beta-Catenin is not necessary for maintenance or repair of the bronchiolar epithelium. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2009;41:535–543. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0407OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Volckaert T, et al. Fgf10-Hippo epithelial-mesenchymal crosstalk maintains and recruits lung basal stem cells. Dev. Cell. 2017;43:48–59.e45. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Volckaert, T. et al. Hippo signaling promotes lung epithelial lineage commitment by curbing Fgf10 and beta-catenin signaling. Development146, dev166454 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78.Volckaert T, et al. Parabronchial smooth muscle constitutes an airway epithelial stem cell niche in the mouse lung after injury. J. Clin. Investig. 2011;121:4409–4419. doi: 10.1172/JCI58097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Reynolds SD, et al. Conditional stabilization of beta-catenin expands the pool of lung stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1337–1346. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Xi Y, et al. Local lung hypoxia determines epithelial fate decisions during alveolar regeneration. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017;19:904–914. doi: 10.1038/ncb3580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lee JH, et al. Anatomically and functionally distinct lung mesenchymal populations marked by Lgr5 and Lgr6. Cell. 2017;170:1149–1163 e1112. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zepp JA, et al. Distinct mesenchymal lineages and niches promote epithelial self-renewal and myofibrogenesis in the lung. Cell. 2017;170:1134–1148 e1110. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nabhan AN, Brownfield DG, Harbury PB, Krasnow MA, Desai TJ. Single-cell Wnt signaling niches maintain stemness of alveolar type 2 cells. Science. 2018;359:1118–1123. doi: 10.1126/science.aam6603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Flozak AS, et al. Beta-catenin/T-cell factor signaling is activated during lung injury and promotes the survival and migration of alveolar epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:3157–3167. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.070326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zemans RL, et al. Neutrophil transmigration triggers repair of the lung epithelium via beta-catenin signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:15990–15995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110144108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Malleske DT, Hayes D, Jr., Lallier SW, Hill CL, Reynolds SD. Regulation of human airway epithelial tissue stem cell differentiation by beta-catenin, P300, and CBP. Stem Cells. 2018;36:1905–1916. doi: 10.1002/stem.2906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rieger ME, et al. p300/beta-catenin interactions regulate adult progenitor cell differentiation downstream of WNT5a/protein kinase C (PKC) J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:6569–6582. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.706416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mori M, et al. Generation of functional lungs via conditional blastocyst complementation using pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Med. 2019;25:1691–1698. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0635-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tadokoro T, et al. IL-6/STAT3 promotes regeneration of airway ciliated cells from basal stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:E3641–E3649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409781111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gouon-Evans V, et al. BMP-4 is required for hepatic specification of mouse embryonic stem cell-derived definitive endoderm. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:1402–1411. doi: 10.1038/nbt1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.D’Amour KA, et al. Efficient differentiation of human embryonic stem cells to definitive endoderm. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:1534–1541. doi: 10.1038/nbt1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Green MD, et al. Generation of anterior foregut endoderm from human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:267–272. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Christodoulou C, et al. Mouse ES and iPS cells can form similar definitive endoderm despite differences in imprinted genes. The. J. Clin. Investig. 2011;121:2313–2325. doi: 10.1172/JCI43853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gomperts BN. Induction of multiciliated cells from induced pluripotent stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 111, 6120–6121 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 95.Mou H, et al. Generation of multipotent lung and airway progenitors from mouse ESCs and patient-specific cystic fibrosis iPSCs. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:385–397. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wong AP, et al. Directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into mature airway epithelia expressing functional CFTR protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30:876–882. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Huang SX, et al. The in vitro generation of lung and airway progenitor cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Protoc. 2015;10:413–425. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]