Abstract

Very preterm infants are at risk for germinal matrix hemorrhage- intraventricular hemorrhage (GH-IVH). Severe GH-IVH may cause death or severe neurodevelopmental disability while mild GH-IVH is considered a static, non-progressive disease. This retrospective study aimed to determine if infants with no GH-IVH or mild GH-IVH on initial screening head ultrasound (HUS) advanced to severe GH-IVH. A total of 353 eligible infants with birth gestational age ≤32 0/7 weeks who received a HUS during hospitalization were identified. Of the 343 (97%) infants who had mild GH-IVH (grade II or less) on initial screening, only 4 (1.2%) progressed to severe (grade III or IV). Each of these infants required mechanical ventilation for at least 40 days. Therefore, premature infants who have no GH-IVH or mild GH-IVH on initial routine screening HUS without other risk factors may not require follow-up HUSs. Infants with prolonged mechanical ventilation may require further screening despite reassuring initial HUS findings.

Keywords: intraventricular hemorrhage, head ultrasound, preterm birth

Background

Premature infants are known to be at increased risk for germinal matrix hemorrhage- intraventricular hemorrhage (GH-IVH) in the first week of life.1 Prematurity is the most important neonatal risk factor for GH-IVH. The risk of developing GH-IVH decreases with each additional week of gestation.2,3 Other postnatal factors that are associated with an increased risk of developing GH-IVH include respiratory distress with episodes of hypocapnia, hypercapnia, hypoxia, and/or acidemia,4 or mechanical ventilation.5 Both respiratory distress and mechanical ventilation are thought to influence changes in cerebral blood flow and central venous pressure and thus may contribute to GH-IVH development.5

Due to advances in neonatal care over the past 10 years, the mortality of preterm infants has decreased.6 However, the incidence of GH-IVH remains significant. In 2018, GH-IVH was reported in 24.2% of infants born <32 weeks, with the highest risk in 22 to 23 6/7 weekers (36.1%). The risk decreased with increasing gestational age (GA)—20.8% in 24 to 25 6/7, 9.5% in 26 to 27 6/7, 3.3% in 28 to 29 6/7 and 1.2% in 30 to 31 6/7.7 Severe GH-IVH (grade III and IV) is associated with reduced survival of premature infants and enhances the risk of several later neurological complications.1,8,9

Significant GH-IVH may be present in the absence of obvious immediate clinical symptoms. Standard screening protocols to identify GH-IVH have therefore become routine. Cranial or head ultrasonography (HUS) is most commonly used to diagnose GH-IVH.1,10 In premature infants, GH-IVH almost exclusively presents within the first 5 days of life, with 50, 25, 15, and 10% of cases occurring on the first, second, third, and fourth and beyond days of life (DOL).11,12 Therefore, the current recommendations for HUS screening in preterm infants suggest imaging be performed in the first few days of life.13 Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society recommends screening “on all infants of 30 weeks’ or less gestation once between 7 and 14 days of life and repeated between 36 and 40 weeks’ postmenstrual age” (PMA).14 The repeat HUS is to screen for new GMH-IVH, PVL, and PHVD. However, there is no universally accepted standard of care for initial HUS screening.

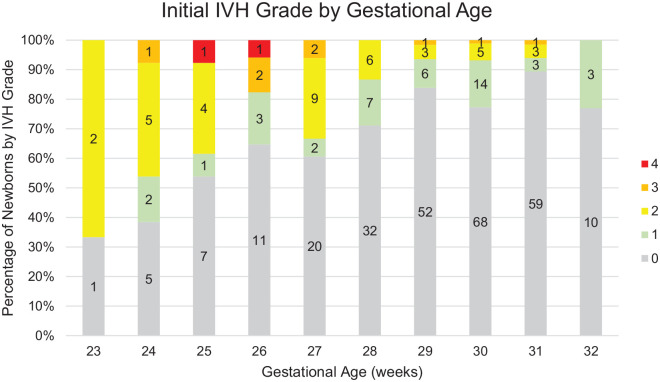

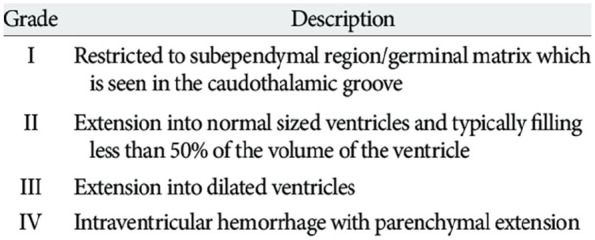

The severity of GH-IVH is determined by the extent of the bleeding, whether it is limited to the germinal matrix region or if it involves the adjacent ventricular system or white matter (Figure 1).13 Grades I and II are considered mild and grades III and IV severe. GH-IVH may be either unilateral or bilateral and either symmetric or asymmetric. Mild GH-IVH is less frequently associated with later morbidity. The presence of severe GH-IVH may lead to severe neurodevelopmental disability or death.

Figure 1.

Papile grading system of intraventricular hemorrhage.

GH-IVH is generally considered a static, rather than progressive disease. Thus, infants with low grade GH-IVH or those that do not present with GH-IVH are unlikely to advance to a higher grade in the absence of significant clinical deterioration. The majority of GH-IVH cases that are initially classified as mild (grade I or II) GH-IVH resolve spontaneously and less frequently result in long-term complications. If infants with a normal HUS and those with mild GH-IVH are unlikely to progress or suffer long term complications, subsequent head ultrasounds may be unnecessary. The purpose of this study is to determine the likelihood of progression of GH-IVH after initial screening in preterm neonates.

Methods

This is a retrospective, single-center study. Institutional review board approval was obtained per hospital protocol. We identified all preterm infants with a birth gestational age ≤32 0/7 weeks admitted the institutions tertiary level Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2016 with available HUS during hospitalization. Screenings were performed by trained ultrasound technicians specialized in neonatal ultrasonography. Sonographic evaluation via the anterior fontanelle, posterior fontanelle, and a right transmastoid approach was performed portably in the NICU using a curved 8 to 5 MHz probe and a linear 17 to 5 MHz probe. Each HUS was classified according to the attending radiologist’s documentation at that time. Grades of GH-IVH were defined per the Papile classification.15 The standard protocol in the UMMMC NICU is consistent with national guidelines, and includes a screening ultrasound once in the first week of life and a second follow-up HUS, at either DOL 28 or 36 weeks PMA, whichever comes first. Initial HUS was defined as HUS performed on DOL 3 to 10 per our institution’s protocol; HUS obtained prior to DOL#3 were assumed to be ordered for clinical suspicion of GH-IVH due to symptoms and not for routine screening. DOL 3, and not before, is chosen to ensure we capture 90% of GH-IVH on our initial HUS, and do not miss those that develop GH-IVH after DOL 1.6,13 Subsequent HUS studies throughout the hospitalization were also graded and recorded. Although we did not have a standardized validated classification system in this study, to reduce potential inter-rater discrepancies, 1 blinded radiologist reviewed a random selection of HUS studies (100% of grades 3 and 4 and 10% of grades 1 and 2) from our cohort to ensure consistency of final interpretations. On review, the independent reviewer did not find any changes in severity, mild GH-IVH remained mild and severe cases of GH-IVH were confirmed and remained severe.

Other information collected included demographic information, antenatal steroid use, bacterial sepsis or meningitis, diagnosis of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), days on a ventilator, respiratory support at 36 weeks, steroids for chronic lung disease, oxygen at discharge, and hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy.

Results

We identified 682 preterm infants who met gestational age eligibility criteria. Of these, 237 had an initial HUS outside of the inclusion time (DOL 3-10) and 88 were excluded due to no HUS performed. A total of 4 infants were excluded for other genetic/congenital conditions associated with GH-IVH. Our final cohort included 353 infants suitable for GH-IVH analysis (Figure 2). The infants who had early HUS performed were statistically different from the study cohort. The infants who did not have a screening HUS performed were all close to 32 0/7 weeks gestation without other risk factors (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Initial GH-IVH grade for infants with initial HUS DOL 3-10.

Table 1.

Demographics.

| Demographics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study cohort N = 353 | Excluded cohort (Infants with HUS performed DOL 0-2) N = 230 | P value | |

| Birth gestational age, weeks (mean, SD) | 28.89 (2.02) | 26.82 (2.45) | <.0001 |

| 23 weeks (n, %) | 3 (0.8) | 18 (7.8) | <.00001 |

| 24 weeks (n, %) | 13 (3.7) | 30 (13.0) | <.00001 |

| 25 weeks (n, %) | 13 (3.7) | 27 (11.7) | .0002 |

| 26 weeks (n, %) | 17 (4.8) | 39 (17.0) | <.00001 |

| 27 weeks (n, %) | 33 (9.3) | 24 (10.4) | .666 |

| 28 weeks (n, %) | 45 (12.7) | 25 (10.9) | .495 |

| 29 weeks (n, %) | 62 (17.6) | 28 (12.2) | .078 |

| 30 weeks (n, %) | 88 (24.9) | 18 (7.8) | <.00001 |

| 31 weeks (n, %) | 66 (18.7) | 16 (7.0) | .0001 |

| 32 weeks (n, %) | 13 (3.7) | 4 (1.7) | .173 |

| Birth weight, grams (mean, SD) | 1214.54 (323.82) | 967.80 (348.39) | <.0001 |

| Male/Total (n, %) | 194 (55.0) | 123 (53.5) | .726 |

| Race (n, %): | .030 | ||

| Black | 47 (13.3) | 46 (20.0) | |

| White | 284 (80.5) | 168 (73.0) | |

| Asian | 14 (4.0) | 5 (2.2) | |

| Other | 8 (2.3) | 11 (4.8) | |

| Rate of antenatal steroids (n, %) | 332 (94.1) | 205 (89.1) | .031 |

| Bacterial sepsis, on or before DOL3 (n, %) | 3 (0.8) | 3 (1.3) | .595 |

| Sepsis or meningitis, late after DOL3 (n, %) | |||

| Bacterial (n, %) | 10 (2.8) | 30 (13.0) | <.00001 |

| Coagulase negative staph (n, %) | 6 (1.7) | 7 (3.0) | .283 |

| Fungal (n, %) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.9) | .333 |

| Any respiratory support at 36 weeks (Chronic Lung disease) (n, %) | 67 (19.0) | 98 (42.6) | <.00001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 3 (0.8) | 7 (3.0) | .046 |

| High frequency oscillatory ventilation | 1 (0.3) | 0 | .419 |

| High flow nasal canula | 18 (5.1) | 47 (20.4) | <.00001 |

| Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation | 5 (1.4) | 8 (3.5) | .099 |

| Continuous positive airway pressure | 8 (2.3) | 6 (2.6) | .792 |

| Oxygen at discharge | 31 (8.8) | 48 (20.9) | <.00001 |

| Steroids for chronic lung disease (n, %) | 28 (7.9) | 58 (25.2) | <.00001 |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) (n, %) | 20 (5.7) | 19 (8.3) | .220 |

| Surgery for NEC, suspected NEC, or bowel perforation (n, %) | 5 (1.4) | 10 (4.3) | .029 |

| Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (n, %) | 0 | 0 | |

The initial HUS was negative for GH-IVH in 265 of the 353 (75%) infants included (Figure 2). Of these, only 2 infants progressed to severe GH-IVH (grade III in both cases). Seventy-eight infants had an initial HUS of mild GH-IVH (grade I/II) and only 2 infants progressed to severe GH-IVH (both grade III).

Of the 343 (97%) infants who had an initial grade 0-II GH-IVH, only 4 babies (1.2%) were found to have a grade III GH-IVH on subsequent HUS (Table 2). Closer evaluation of the clinical course of these 4 infants revealed a unifying factor—prolonged ventilator requirement. Each of these infants had increased days on ventilator (>40 days). The average days on a ventilator for these infants was 58.75 days compared with 8.85 days (P < .0001) in the cohort of infants that did not progress to a more severe grade but required ventilatory support (N = 137). Sixty-nine percent of infants with severe GH-IVH on their highest HUS screening required a ventilator for ≥30 days. Average days on a ventilator was 26.67, 23, 8.51, 4.31, and 2.24 for GH-IVH grades IV, III, II, I, and no GH-IVH, respectively. Severe GH-IVH grade III/IV was uncommon in this cohort and recognized in only 10/353 infants.

Table 2.

Matrix of GH-IVH Progression—Comparing Initial & Subsequent GH-IVH Grade for Infants with Initial HUS DOL 0-10 (All Infants).

| Initial IVH grade vs. Final IVH grade for all infants with HUS DOL 0-10 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial IVH grade (N, %) | Final IVH grade (N, %) | ||||||

| Total on initial HUS (N, %) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 0 | 403 (69.1) | 292 (50.1) | 74 (12.7) | 30 (5.1) | 5 (0.9) | 2 (0.3) | |

| 1 | 78 (13.4) | 58 (9.9) | 17 (2.9) | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | ||

| 2 | 79 (13.6) | 76 (13.0) | 3 (0.5) | 0 (0) | |||

| 3 | 13 (2.2) | 10 (1.7) | 3 (0.5) | ||||

| 4 | 10 (1.7) | 10 (1.7) | |||||

| Total | 583 | 292 (50.1) | 132 (22.6) | 123 (21.1) | 20 (3.4) | 16 (2.7) | |

To determine if inclusion of the infants that received HUS for clinical suspicion (DOL 0-2) changed the outcome of GH-IVH progression, we also performed data analysis including this cohort. Of the 237 that were excluded for having HUS outside of the screening window, 230 had HUS on DOL 0-2 totaling 583 infants to be analyzed. 560 (96%) of these had mild GH-IVH (grade II or less) and only 13 (2.3%) progressed to a more severe grade (Table 3). The progression was statistically different among the cohorts with 1.2% in the study cohort and 4.1% in the excluded infants (P = .0393). Thirteen (5.7%) of these infants had severe GH-IVH on initial HUS compared with 3% in the study cohort (Table 4). On initial HUS, 8 (3.5%) infants in the excluded cohort had grade IV GH-IVH versus 2 (0.6%) infants in the study cohort (P = .0169).

Table 3.

Matrix of GH-IVH Progression—Comparing Initial & Subsequent GH-IVH Grade for Infants with Initial HUS DOL 0-2 (Excluded Cohort).

| Initial IVH grade vs. Final IVH grade for infants with HUS DOL 0-2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial IVH grade (N, %) | Final IVH grade (N, %) | ||||||

| Total on Initial HUS | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 0 | 138 (60.0) | 85 (37.0) | 29 (12.6) | 19 (8.3) | 3 (1.3) | 2 (0.9) | |

| 1 | 37 (16.1) | 22 (9.6) | 13 (5.7) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | ||

| 2 | 42 (18.3) | 40 (17.4) | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0) | |||

| 3 | 5 (2.2) | 3 (1.3) | 2 (0.9) | ||||

| 4 | 8 (3.5) | 8 (3.5) | |||||

| Total | 230 | 85 (37.0) | 51 (22.2) | 72 (31.3) | 9 (3.9) | 13 (5.7) | |

Table 4.

Matrix of GH-IVH Progression—Comparing Initial & Subsequent GH-IVH Grade for Infants with Initial HUS DOL 3-10 (Study Cohort).

| Initial IVH grade vs. Final IVH grade | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial IVH grade (N, %) | Final IVH grade (N, %) | ||||||

| Total on Initial HUS (N, %) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 0 | 265 (75.0) | 207 (58.6) | 45 (12.7) | 11 (3.1) | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0) | |

| 1 | 41 (11.6) | 36 (10.2) | 4 (1.1) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | ||

| 2 | 37 (10.5) | 36 (10.2) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | |||

| 3 | 8 (2.3) | 7 (2.0) | 1 (0.3) | ||||

| 4 | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.6) | |||||

| Total | 353 | 207 (58.6) | 81 (22.9) | 51 (14.4) | 11 (3.2) | 3 (0.9) | |

The difference in GA and birth weight between the infants who had an early HUS performed (excluded cohort) and the study cohort were statistically significant (P < .0001, in both cases). The average birth weight in these infants was 967.8 g, compared to 1214.54 g in the cohort which received their initial HUS between DOL 3 to 10. As well, the excluded cohort had significantly more black infants than study cohort (P = .03). Incidence of bacterial sepsis was significantly different affecting 13% of infants in this cohort vs 2.8% in the study cohort (P < .0001). Surgery for necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), suspected NEC, or bowel perforation was also significantly higher with 4.3% in the excluded cohort versus 1.4% in the study cohort (P = .029). Infants in the excluded cohort also required respiratory support at 36 weeks more frequently than the study cohort, 42.6% and 19.0%, respectively (P < .00001). Significantly more infants required oxygen at discharge in the excluded cohort (20.9%) compared to the study cohort (8.8%) (P < .0001). In addition, the difference in need for steroids for chronic lung disease was statistically significant with 25.2% in the excluded cohort versus 7.9% in the study cohort (P < .0001). The study cohort required more antenatal steroids, 94.1%, than the 89.1% in the excluded cohort (P = .031).

The average number of HUS performed throughout hospitalization in our cohort was 3, but ranged anywhere from 0 to 18. Potentially unnecessary HUS studies were defined as any additional HUS study performed on infants with no GH-IVH or mild GH-IVH on initial HUS in excess of the initial and 36-week PMA study. Of the 970 HUS performed on babies with grade II GH-IVH or less, 331 (34%) were categorized as potentially unnecessary.

Of the HUSs that were reread, 76% were graded the same and 22% differed by a single grade. Of the 22%, no HUS interpretation changed from mild to severe GH-IVH during this regrade.

Discussion

GH-IVH is a common problem in premature neonates that can lead to significant neurological complications and even death. Our study reveals an overall GH-IVH incidence of 25% confirming the high prevalence in preterm infants. Fortunately, most cases were low grade; 22% were classified as mild GH-IVH (grade I and II) and only 3% were classified as severe GH-IVH (grade III and IV). The standard protocol in our NICU is consistent with national guidelines and includes a screening HUS once in the first week of life and a second follow-up HUS, at either DOL 28 or 36 weeks PMA, whichever comes first. It is generally assumed that infants with no GH-IVH or low grade GH-IVH do not progress. Our study revealed that the rate of progression was indeed quite low in our cohort, with only 4 out of 343 (1.2%) progressing from a negative or mild GH-IVH to a severe grade. Each of these 4 infants required mechanical ventilation for at least 40 days. Thus, in the absence of prolonged mechanical ventilation or clinical suspicion of clinical deterioration, our data suggests that additional HUS studies for mild cases of GH-IVH may be extraneous. It is possible the progression seen represents post-hemorrhagic ventricular dilation (PHVD) and not progression to a more severe GH-IVH grade. However, PHVD is typically a result of severe GH-IVH and thus we would not expect mild GH-IVH to lead to PHVD.16-18

Concern for progression of GH-IVH warrants performance of additional HUS. However, in the absence of clinical deterioration or suspicion of worsening of HUS, additional HUS studies may be unnecessary. Three hundred thirty-one HUSs in our cohort were felt to be potentially unnecessary; chart review did not reveal risk factors for GH-IVH progression (hypotension, sudden onset of anemia, etc.). HUS studies are relatively low cost, minimally invasive, and the scans and results can be completed quickly, typically within hours. However, babies in the NICU are typically quite ill, connected to multiple monitors, and are subjected to many different screening tests, procedures, and exams. Reducing any one of these diminishes the burden on the baby. HUSs also require time and resources of NICU providers and staff. Eliminating even a fraction of the 331 HUSs considered excessive would translate into significant cost savings as well as a savings of valuable NICU time and resources.

In our analysis, we excluded 237 infants because they did not receive a HUS during DOL 3 to 10. While this is a substantial portion of our population, our hospital’s protocol for routine head ultrasound screening begins at DOL 3. This is because any HUS performed before DOL3 is done primarily for clinical suspicion of GH-IVH and not for routine screening. In fact, because of the potential for false negative scans on DOL1, and the increased sensitivity of later head ultrasounds, most institutions have initial screens on DOL3, as is our policy. HUS performed prior to DOL 3 are more commonly conducted, not for routine screening, but for clinical suspicion of hemorrhage. However, given this large portion of infants, we reran our analyses on the total cohort. Of the 237 excluded infants, 230 had scans on DOL 0 to 2 indicating a strong clinical suspicion in the group. If an infant’s clinical course is severe enough to require HUS before DOL 3, their chance of having an abnormal HUS increases significantly. However, the focus of this study was to look at the progression of standard screening HUS based on risk factors, and not clinical status.

When examined the outcomes of the 230 infants, they differed in a number of ways, including demographics, clinical course, and progression of GH-IVH. Infants who received a HUS prior to DOL 3 had lower birth GA and birth weight which is identified as a risk factor for GH-IVH. We noted that significantly more infants had grade IV GH-IVH on initial HUS in the excluded cohort. The average birth weight was significantly lower in the excluded cohort (967.8 g), considered extremely low birth weight, in comparison to the study cohort who had an average birth weight of 1214.54 g. Significantly more infants developed bacterial sepsis, required steroids for chronic lung disease, were still on oxygen at 36 weeks, and were more likely to be discharged home on supplemental oxygen. They also had significantly more surgery for NEC, suspected NEC or bowel perforation, further supporting that these babies were indeed sicker, more complicated infants. In fact, these infants’ GH-IVH progression was more frequent than our original cohort’s pattern, suggesting these infants had severe clinical courses requiring HUS’s for clinical suspicion and not routine screening. Thus, excluding these cases allowed us to appropriately focus on evaluating GH-IVH progression during routine head ultrasound screening. Even so, the overall progression of GH-IVH in both cohorts of infants with no GH-IVH or mild GH-IVH on initial HUS was still quite low (2.3%), proving that mild GH-IVH rarely progresses to a more severe grade.

Surprisingly, 88 infants lacked HUS data and were also excluded which may have impacted our results. However, most of these infants were > 30 weeks GA and thus, a HUS was presumably deemed unnecessary by attending neonatologist. Still, the protocol is in place to detect GH-IVH early and to minimize neurologic injury. The finding that many premature infants did not have an ultrasound or had an ultrasound outside of the protocol window has prompted a quality improvement project and focus on protocol compliance at our institution to address this concern.

HUSs remain a necessary screening tool, allowing clinicians to identify babies with more severe grades of GH-IVH. Those infants that are determined to have grade III or IV GH-IVH, may require intervention including shunting, drainage, or even craniotomy. The screening HUS at 28 weeks or 36 weeks gestational age is performed to screen for periventricular leukomalacia (PVL). PVL is coagulative and necrotic injury of the white matter of the brain near the lateral ventricles which can result in severe neurologic deficits.14 Early detection and treatment is important for successful outcomes in both of these high-risk populations.

The limitations of this study include the retrospective chart review study design as well as being a single-center cohort. The potential inter-radiologist variability was addressed by having 1 radiologist read and grade a random sampling of HUS in our study and cross-reference accuracy to verify validity. Of the randomly sampled HUSs that were reread, no HUS interpretation changed from mild to severe GH-IVH during this regrade; those that were originally graded as mild GH-IVH were graded as mild GH-IVH this time, as well. We interpreted these findings as confirmation that there is minimal radiologist variability, and any variability that is present does not impact the severity of the grading.

This is one of the larger single-center studies in the current literature. Given the rapid changes in the field of neonatology (differences in utilization of steroids, changes in surfactant utilization, and ventilator management strategies, etc.) this study also reflects more recent neonatology practice, as the larger prior epidemiologic studies describing GH-IVH and HUS screening recommendations were published over 7 years ago.2,3,14

Conclusion

GH-IVH is a common condition affecting preterm infants with a birth gestational age ≤ 32 0/7. Based on the results of this analysis, infants who have normal (no GH-IVH) HUS or mild GH-IVH (grade I or II) on initial screening HUS without other risk factors are unlikely to progress and may not require a follow-up HUS for GH-IVH. Infants with prolonged mechanical ventilation may require further screening despite initial low-grade HUS findings. As well, infants who receive a HUS due to clinical suspicion prior to DOL 3 or have other risk factors for progression, such as low birth weight and GA, should still receive screening follow-up HUS. All infants should still receive a HUS at 36 weeks or prior to discharge to screen for white matter injury, cystic PVL, brain atrophy, and PHVD. Future research will help to standardize GH-IVH screening protocols within NICUs.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the NICU research team at University of Massachusetts Memorial Hospital and the University of Massachusetts Memorial NICU Staff. The University of Massachusetts Medical School Summer Research Program provided funding for JD.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: JD, HW, AD, QS, JMG, LR, all made a substantial contribution to the concept or design of the work; or acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data, JD drafted the article and HW, LR revised it critically for important intellectual content, All authors approved the version to be published.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The research was partially funded by the University of Massachusetts Medical School Summer Student Research Program.

Availability of Data and Material: The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent: The study was approved by the University of Massachusetts Medical School Institutional Review Board and written informed consent was waived due to the retrospective design of the study (Study Docket Number, H00012820).

Consent for Publication: All authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Research Ethics and Patient Consent: The study protocol was approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects in Research, the University of Massachusetts Medical School Institutional Review Board.

ORCID iD: Lawrence Rhein  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5703-8833

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5703-8833

References

- 1. Ballabh P. Intraventricular hemorrhage in premature infants: mechanism of disease. Pediatr Res. 2010;67:1-8. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181c1b176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, et al. Neonatal outcomes of extremely preterm infants from the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics. 2010;126:443-456. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bajwa NM, Berner M, Worley S, Pfister RE, Swiss Neonatal N. Population based age stratified morbidities of premature infants in Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly. 2011;141:w13212. doi: 10.4414/smw.2011.13212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Altaany D, Natarajan G, Gupta D, Zidan M, Chawla S. Severe intraventricular hemorrhage in extremely premature infants: are high carbon dioxide pressure or fluctuations the culprit? Am J Perinatol. 2015;32:839-44. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1543950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aly H, Hammad TA, Essers J, Wung JT. Is mechanical ventilation associated with intraventricular hemorrhage in preterm infants? Brain Dev. 2012;34:201-205. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2011.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Horbar JD, Edwards EM, Greenberg LT, et al. Variation in performance of neonatal intensive care units in the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:e164396. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.4396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Handley SC, Passarella M, Lee HC, Lorch SA. Incidence trends and risk factor variation in severe intraventricular hemorrhage across a population based cohort. J Pediatr. 2018;200:24-29 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.04.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Linsell L, Malouf R, Morris J, Kurinczuk JJ, Marlow N. Risk factor models for neurodevelopmental outcomes in children born very preterm or with very low birth weight: a systematic review of methodology and reporting. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185:601-612. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Luu TM, Ment LR, Schneider KC, Katz KH, Allan WC, Vohr BR. Lasting effects of preterm birth and neonatal brain hemorrhage at 12 years of age. Pediatrics. 2009; 123:1037-1044. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lalzad A, Wong F, Schneider M. Neonatal cranial ultrasound: are current safety guidelines appropriate? Ultrasound Med Biol. 2017;43:553-560. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2016.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Adcock LM. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of intraventricular hemorrhage in the newborn. UpToDate; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nwafor-Anene VN, DeCristofaro JD, Baumgart S. Serial head ultrasound studies in preterm infants: how many normal studies does one infant need to exclude significant abnormalities? J Perinatol. 2003;23:104-110. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7210869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kwon SH, Vasung L, Ment LR, Huppi PS. The role of neuroimaging in predicting neurodevelopmental outcomes of preterm neonates. Clin Perinatol. 2014;41:257-283. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2013.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ment LR, Bada HS, Barnes P, et al. Practice parameter: neuroimaging of the neonate: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2002;58:1726-1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Papile LA, Burstein J, Burstein R, Koffler H. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: a study of infants with birth weights less than 1,500 gm. J Pediatr. 1978;92:529-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wilson D, Kim D, Breibart S. Intraventricular hemorrhage and posthemorrhagic ventricular dilation: current approaches to improve outcomes. Neonatal Netw. 2020;39:158-169. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.39.3.158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Leijser LM, Miller SP, van Wezel-Meijler G, et al. Posthemorrhagic ventricular dilatation in preterm infants: when best to intervene? Neurology. 2018;90:e698-e706. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Murphy BP, Inder TE, Rooks V, et al. Posthaemorrhagic ventricular dilatation in the premature infant: natural history and predictors of outcome. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2002;87:F37-F41. doi: 10.1136/fn.87.1.f37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]