Abstract

Introduction:

Successful sex is one of the greatest behavioral needs of couples, especially those who marry at an early age. The best way to access information is education and learning. Face to face training is one of the most common methods, with the advancement of technology, multimedia training can be a good alternative method to sex education. This study was designed to comparison between two educational method Multimedia and Face to face on sexual function of Afghan Migrant Adolescent Women.

Methods:

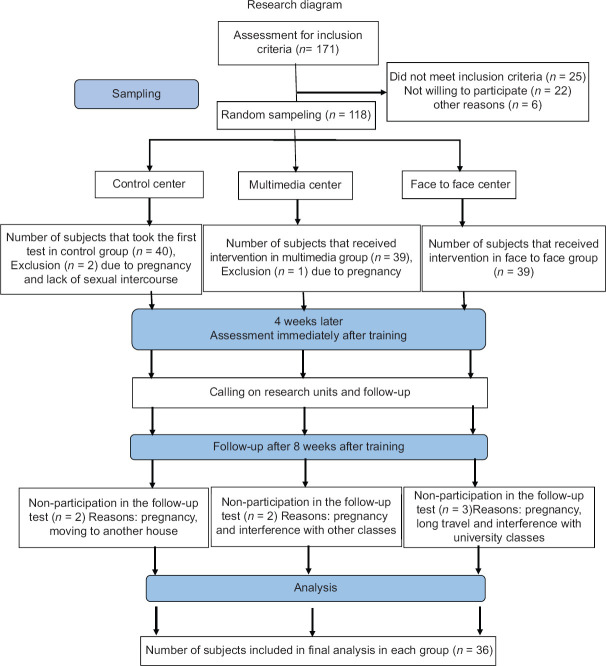

The study was a quasi-experimental educational intervention conducted in selected charity centers in Mashhad. The selected centers were randomly chosen as face to face intervention (n = 36), multimedia intervention (n = 36) and control (n = 36) groups. Our method of sampling was convenient at each center. Intervention groups received four one-hour sessions of sex education using various face to face and multimedia methods. Sexual function were measured using female sexual function index (FSFI) before, immediately and 8 weeks after the intervention. Data were analyzed with SPSS version 16.

Results:

The level of sexual function did not show a significant difference in groups before the intervention, but these increased significantly immediately (P = 0.005) and 8 weeks later (P < 0.001).

Conclusion:

Because of the taboo of sexual issues and the lack of difference between the two methods in improving sexual function, multimedia method is a good alternative educational method.

Keywords: Face to face, multimedia, sex education, sexual function

Introduction

More than one-third of women marry in adolescence,[1] and half of these marriages occur in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.[2] Afghanistan is one of the South Asian countries[3] And the 2016 census shows the extensive migration of Afghans to Iran.[4,5] Teen marriage occurs in some Afghan ethnic populations due to deep cultural roots and weak socioeconomic status.[3,6] There are no accurate statistics of Afghan migrants' marriage in Iran.[7] According to the National organization for Civil Registration website in 2015, the largest population group for marriage is for women aged 15-19 years.[8] Although open communication between parents and their children regarding sex-related issues is important[9] but unfortunately it is forbidden to talk about marriage and sex in Afghan society.[3] One of the factors affecting the success of sexual relationship is satisfaction with married life which depend on sexual function[10] and plays an important role in the health, quality of life and life satisfaction of the couples.[11] Due to the high prevalence of sexual dysfunction[12,13,14] and existence a relationship between sexual Function and age in women, which underlines the importance of sexual education at lower ages.[15] Lack of adequate knowledge and incorrect attitudes regarding sexual matters.[16,17] are among factors affecting divorce, especially among newly married couples.[18,19] The best tool to achieve a desirable sexual Function is education and creating a positive attitude towards sexual matters.[20,21] Sex education is one of the priorities of women's health[22] and has been heralded as effective in promoting sexually healthy behavior in youth.[23,24,25] Even with the spread of sex education in developing countries compared to the past,[26] Cultural background and some strict rules may be effective in the failure of sex education.[27] Therefore, synchronizing the education with cultural norms of the society that is compatible with the needs of the target group with regards to the religious background of these societies may be very helpful.[28,29,30] Face to Face training is common and traditional methods of education in the health care system.[31,32] Given the widespread use of technology and the success of sex education in European countries,[33,34] the use of new methods of sex education and update and modernize standards[35] in Islamic countries seems to be necessary given the taboo of sexual issues.[3,36,37] Multimedia is a new and interesting educational method that encourages learning.[38,39] Sexual matters cannot be discussed openly according to cultural norms in Iran and[3,37] and Not addressing these barriers[40] may undermine the policy's intention of increasing knowledge about sexuality and reproduction,[41] Therefore, this study was conducted to determine the comparison between two educational method Multimedia and Face to face about Sexual issues on sexual function of Afghan Migrant Adolescent Women.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This study was a quasi-experimental educational intervention conducted in 2018 on 108 women who referring to three selected charity centers in three immigrant neighborhoods of Mashhad.

Inclusion criteria

Young Afghan females aged 10-24 years who could communicate in Farsi, married officially, were the only wives of her husbands, married for at least one year, did not receive official sexual education in the past, lacked medical diseases, were not addicted to opium and psychedelics, did not experience stressful events in the past six months, were not pregnant or lactating, did not have an abortion in the past three months, lived with her husband, had sexual intercourse with him, had access to a computer or CD player and knew how to work with them.

Exclusion criteria

Pregnancy, lack of sexual intercourse and occurrence of stressful events during the study, withdrawal from the study and missing the third and fourth educational sessions.

Sample size

To determine the sample size according, use the formula  [42] and k = 3, ƛ was calculated as 12.66. Δ was calculated as follows from past study[43] and sample size was calculated 40 in each group with 10% of the falls.

[42] and k = 3, ƛ was calculated as 12.66. Δ was calculated as follows from past study[43] and sample size was calculated 40 in each group with 10% of the falls.

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (Ethics approval code: IR.IUMS.REC1397.027) and registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (Registration code: IRCT20180611040054N1). The study started after obtaining approval from Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (approval number: 97/32620).

Data collection

Data collection was done by demographic and FSFI questionnaires that were completed by self-report. The FSFI is a 19-item questionnaire that evaluates female sexual Function in 6 domains of desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain. It was developed by Rosen et al. The six domain scores are added to obtain the full scale score, ranging from 2 to 36.[44] In Iran, the validity of the Persian version of the tool had been approved by Fakhri et al.[45]

Procedure

After receiving ethical clearance, an introduction letter was issued by Iran University of Medical Sciences, which was presented to Mashhad University of Medical Sciences. Then, three charity centers in three different suburbs regions of the Mashhad city that had the largest number of female Afghan visitors were selected. The selected centers were divided into face to face intervention, multimedia intervention and control groups by lottery. The eligible subjects were enrolled and informed consent was obtained from them. Then, they were asked to complete the demographic and FSFI questionnaire. In addition to routine programs of the center, the subjects in the face to face group received four one-hour sex education sessions in four sessions, one session per week. Multimedia group received 4 CDs, one CD per week, for four weeks. Giving the next CD was dependent on the researcher's assurance of observing the previous. Details of the content of the sex education sessions follow. First session: male and female reproductive organs, menstrual cycle, puberty, masturbation, reproductive health. Second session: normal and abnormal vaginal discharge, gynecologic infections, contraceptive methods. Third session: importance of sexual relationship in married life, communication skills for couples, methods to improve the quality of sex, different sex positions, married life in Islam, legal rights of couples. Forth session: normal sexual cycle stages, sexual disorders and treatment. Finally, the FSFI were completed by all subjects. To evaluate the durability of this educational methods, the subjects were contacted via phone to attend the center and complete the questionnaires after 8 weeks. The control group only received routine programs of the charity center and after the study, the multimedia CD was also distributed among them. Data were analyzed using SPSS software version 16 with Descriptive statistics and inferential statistics [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Comparison of trend of sexual Function score changes in groups before and after 4 and 8 weeks after the intervention

Results

According to the results of Chi-square and Fisher's exact tests, the three groups were homogeneous in terms of Demographic characteristics. The data of 108 subjects; 36 in each group, was finally analyzed. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the participants.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants in groups

| Groups | Variable | Mean±SD | Test result | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Face to face | Multimedia | Control | ||||||

| Age | 22/69 (± 0/261) | 22/92 (± 0/197) | 22/39 (± 0/285) | F=1/120; P=0/330 | ||||

| Husband’s age | 28/06 (± 0/343) | 27/64 (± 0/440) | 26/86 (± 0/456) | F=2/123; P=0/125 | ||||

| Age at marriage | 19/67 (± 0/340) | 18/81 (± 0/398) | 19/61 (± 0/322) | F=1/844; P=0/163 | ||||

| Demographic | Variable | Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | Test result |

| Duration of marriage (years) | 1-5 | 34 | 94/4 | 28 | 77/8 | 32 | 88/9 | df=2, P=0/130 |

| 6-10 | 2 | 5/6 | 8 | 22/2 | 4 | 11/1 | ||

| Occupation | Housewife | 34 | 94/4 | 31 | 86/1 | 31 | 86/1 | df=2, P=0/479 |

| Employed | 2 | 5/6 | 5 | 13/9 | 5 | 13/9 | ||

| Education level | Unfinished high school | 11 | 30/6 | 14 | 38/9 | 13 | 36/1 | df=2, χ2=0/568, P=0/753 |

| High school diploma and above | 25 | 69/4 | 22 | 61/1 | 23 | 63/9 | ||

| Husband’s occupation | Employed | 34 | 94/4 | 33 | 91/7 | 34 | 94/4 | df=2, P=1/000 |

| Unemployed | 2 | 5/6 | 3 | 8/3 | 2 | 5/6 | ||

| Husband’s education level | Unfinished high school | 15 | 41/7 | 19 | 52/8 | 15 | 41/7 | df=2, χ2=1/195, P=0/550 |

| High school diploma and above | 21 | 58/3 | 17 | 47/2 | 21 | 58/3 | ||

| Number of children | 0-1 | 32 | 88/9 | 24 | 66/7 | 30 | 83/3 | df=2, χ2=5/937, P=0/051 |

| 2-4 | 4 | 11/1 | 12 | 33/3 | 6 | 16/7 | ||

| Number of pregnancies | 0-1 | 27 | 75/0 | 23 | 63/9 | 28 | 77/8 | df=2, χ2=1/938, P=0/379 |

| 2-4 | 9 | 25/0 | 13 | 36/1 | 9 | 22/2 | ||

| Abortion | Positive | 9 | 25/0 | 6 | 16/7 | 3 | 8/3 | df=2, χ2=3/600, P=0/165 |

| Negative | 27 | 75/0 | 30 | 83/3 | 33 | 91/7 | ||

| Self-selected marriage | Yes | 31 | 86/1 | 34 | 94/4 | 34 | 94/4 | df=2, P=0/500 |

| No | 5 | 13/9 | 2 | 5/6 | 2 | 5/6 | ||

| Living with other people | Yes | 6 | 16/7 | 3 | 8/3 | 7 | 19/4 | df=2, χ2=1/908, P=0/385 |

| No | 30 | 83/3 | 33 | 91/7 | 29 | 80/6 | ||

| Private bedroom | Yes | 26 | 72/2 | 22 | 61/1 | 31 | 86/1 | df=2, χ2=5/751, P=0/056 |

| No | 10 | 27/8 | 14 | 38/9 | 5 | 13/9 | ||

| Economic status | Unfavorable | 3 | 8/3 | 3 | 8/3 | 7 | 19/4 | df=4, P=0/613 |

| Relatively favorable | 27 | 75/0 | 28 | 77/8 | 25 | 69/4 | ||

| favorable | 6 | 16/7 | 5 | 13/9 | 4 | 11/1 | ||

| Average duration of intercourse | 1-10 min | 5 | 13/9 | 10 | 27/8 | 5 | 13/9 | df=4, χ2=4/750, P=0/314 |

| 11-30 min | 24 | 66/7 | 20 | 55/6 | 20 | 55/6 | ||

| 31-60 min | 7 | 19/4 | 6 | 16/7 | 11 | 30/6 | ||

| Number of sexual intercourses per month | 3-8 times | 15 | 41/7 | 21 | 58/3 | 15 | 41/7 | df=4, P=0/157 |

| 9-16 times | 14 | 38/9 | 13 | 36/1 | 19 | 52/8 | ||

| 17-25 times | 7 | 19/4 | 2 | 5/6 | 2 | 5/6 | ||

Discussion

Preventive care is a key focus in a good primary care practice.[46] Sex education affects levels of prevention by affecting sexual health,[47] so that with increased sexual awareness,[48] problems such as divorce will decrease as a result of lack of awareness of sexual issues.[49,50,51,52] It can be said that educational strategies are meant to prevent and increase self-care in individuals. Given that sexual health is a major need, primary care physicians who are at the forefront of communication with clients can help address this need by having sufficient knowledge of sexual issues.[30,53] The use of various health promotion strategies such as multimedia and educational materials in clinics and by primary care physicians, can reduce sexual taboos in developing societies.[54]

In the present study, there was no significant difference in the mean score of sexual Function in the three groups before the intervention (p = 0.957), while significant differences were observed immediately (p = 0.005) and 8 weeks after the intervention (p < 0.001) [Table 2 and Table 3]. Moreover, the difference in desire (p < 0.001), arousal (p < 0.001), lubrication (p < 0.001), orgasm (p < 0.001) satisfaction (p < 0.001) and pain (p = 0.028), was significant.

Table 2.

Comparison the effect of face to face and multimedia sex education on sexual Function in groups before and 4 and 8 weeks after the intervention (n=108)

| Variable | Measurement time | Mean (SD) | F | P (Repeated measured) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After 4 weeks | After 8 weeks | ||||

| Sexual Function |

Face to face | 67/17 (14/52) | 75/78 (12/74) | 77/42 (11/97) | 36/32 | <0/001* |

| Multimedia | 66/56 (13/24) | 73/19 (12/77) | 77/11 (11/57) | 29/47 | <0/001* | |

| Control | 66/19 (14/16) | 65/89 (13/64) | 65/11 (13/36) | 3/604 | 0/054 | |

Table 3.

Comparison the effect of face to face and multimedia sex education on sexual Function in groups before and 4 and 8 weeks after the intervention (n=108)

| Time | Variable | Mean (SD) | P | Mean (SD) | P | Mean (SD) | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After 4 weeks | Before | After 8 weeks | After 4 weeks | After 8 weeks | |||||

| Sexual Function | Face to face | 67/17 (14/52) | 75/78 (12/74) | <0/001* | 67/17 (14/52) | 77/42 (11/97) | <0/001* | 75/78 (12/74) | 77/42 (11/97) | 0/226 |

| Multimedia | 66/56 (13/24) | 73/19 (12/77) | <0/001* | 66/56 (13/24) | 77/11 (11/57) | <0/001* | 73/19 (12/77) | 77/11 (11/57) | <0/001* | |

| control | 66/19 (14/16) | 65/89 (13/64) | 1/000 | 66/19 (14/16) | 65/11 (13/36) | 1/000 | 65/89 (13/64) | 65/11 (13/36) | 1/000 | |

The results of a study by Sabeti et al. showed that participation in sexual health educational sessions improved the score of sexual Function and all of its components that was consistent with the results of this study.[55] The results of a study by Nameni (2014) indicated, sex education effects on the total score of sexual Function and the scores of desire and satisfaction, which is consistent with our results. Lack of consistency in the scores of other components may originate from differences in the age range of the subjects and using immigrants as samples.[56] In a study by Baradaran-Akbarzadeh et al. Sexual function and all its dimensions were improved after intervention in the intervention group.[57]

In this study, face to face and multimedia education could help women through improving the scores of sexual function. In the study of Shams Mofarahe et al.(2019), which examined the effect of face to face marital counseling on couples' sexual satisfaction, the level of sexual satisfaction was higher in the intervention group[58] which all the mentioned studies were consistent with the present study.

In multimedia method, messages are transferred through video or audio media, which enhances message delivery.[59] A study conducted by Jeste et al. also indicated that multimedia could be used for a better interaction together with other services as a complement.[60] One study found that multimedia education improved the awareness of pregnant women regarding warning signs during pregnancy.[61]

This modern educational method can be used for sexual education in Islamic societies considering the taboo nature of these topics and the prevailing cultural, religious, social, and political beliefs in these societies. Preparing a proper sexual educational content for multimedia education decreases the costs of face-to-face education and satisfies the couples' needs for sexual information.

Key point

Most marriages occur in immigrants living in Iran during adolescence.

Women's ignorance of various aspects of sexual issues can lead to the formation of unsuccessful sexual relationships and undesirable sexual function.

Due to the existence of cultural, social and religious barriers in the sexual education of Islamic societies, the use of new educational methods such as multimedia seems necessary.

Limitations

Since all questionnaires were self-reported by the participants. The researcher was a co-host of the participants and by communicating properly they were assured of confidentiality to complete the questionnaires with integrity.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient (s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

This study was part of an MSc thesis project on midwifery conducted at the International Campus of Iran University of Medical Sciences (IUMS) and financially supported by the UNFPA and Italian Embassy.

References

- 1.Basha PC. Child marriage: Causes, consequences and intervention programmes. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research. 2016;2:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNFPA. Marrying too young: End child marriage. New York: United Nation Population Fund; 2012. p. 8. cited 2020 Mar 05. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/MarryingTooYoung.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hadi M. An Analysis of Policy and Social Factors Impacting the Uptake of Sexual and Reproductive Health Services in Kabul, Afghanistan. Durham: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.UNHCR. Global trends forced displacement in 2015 Geneva, Switzerland. 2015. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/statistics/unhcrstats/576408cd7/unhcr-global-trends-2015.html . Last cited on 2020 Mar 04.

- 5.Statics TCoI. The choice of results public statistical from population and residence. Tehran: Statistical centre of Iran. Office of the Head, Public Relations and International Cooperation; 2017. Available from: http://www.amar.org.ir . Last cited on 2020 Mar 12. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Afghanistan CSOotGotIRo. Afghanistan living conditions survey 2016-17 Kabul. 2018. [Last cited on 2019 Mar 03]. Available from: http://cso.gov.af/Content/files/ALCS/ALCS%202016-17%20Analysis%20report%20%20English%20_compressed (1).pdf .

- 7.Saidi S. An ethnographic survey of the phenomenon of early marriage among Afghan immigrants (Hazara People) in two cities of Hamburg (Germany) and Tehran (Iran) Iran J Anthropol Res. 2017;7:73–93. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Registration NOfC. The age distribution of couples during the marriage of 1394/marriage divorce ratio. 2015. Available from: http://www.sabteahval.ir/Upload/Modules/Contents/asset99/e-g-94.pdf . Last cited on 2019 May 15.

- 9.Shin H, Lee JM, Min JY. Sexual knowledge, sexual attitudes, and perceptions and actualities of sex education among elementary school parents. Child Health Nurs Res. 2019;25:312–23. doi: 10.4094/chnr.2019.25.3.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tavakol Z, Mirmolaei ST, Momeni Movahed Z, Mansori A. The relationship between sexual function and sexual satisfaction in women referring to centers sanitary health south of Tehran. Sci J Hamedan Nurs Midwifery Faculty (Nasim Danesh) 2012;19:50–4. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamyabi Nia Z, Azhari S, Mazlom SR, Asghari Pour N. Relationship between religion and sexual function of women of reproductive age. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2016;19:9–19. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fajewonyomi BA, Orji EO, Adeyemo AO. Sexual dysfunction among female patients of reproductive age in a hospital setting in Nigeria. J Health Popul Nutr. 2007;25:101–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghiasi A, Keramat A. Prevalence of sexual dysfunction among reproductive-age women in iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Midwifery Reprod Health. 2018;6:1390–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramezani Tehrani F, Farahmand M, Mehrabi Y, Malkafzali H, Abedini M. Prevalence of female sexual dysfunction and its correlated factors: A population based study. Payesh. 2012;11:869–75. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazinani R, Akbari Mehr M, Kaskian A, Kashanian M. Evaluation of prevalence of sexual dysfunctions and its related factors in women. Razi Journal of Medical Sciences. 2013;19:59–66. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kantor LM, Lindberg L. Pleasure and sex education: The need for broadening both content and measurement. Am J Public Health. 2020;110:145–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meiksin R, Campbell R, Crichton J, Morgan GS, Williams P, Willmott M, et al. Implementing a whole-school relationships and sex education intervention to prevent dating and relationship violence: Evidence from a pilot trial in English secondary schools. Sex Educ. 2020:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaur Ahuja V, Patnaik S, Gurchandandeep, Lugani Y, Sharma N, Goyal S, et al. Perceptions and preferences regarding sex and contraception, amongst adolescents. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8:3350–5. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_676_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pourmarzi D, Rimaz S, Merghati Khoei E. Sexual and reproductive health educational needs in engaged couples in Tehran in 2010. Sex Res Soc Policy. 2014;11:225–32. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Astle S, McAllister P, Emanuels S, Rogers J, Toews M, Yazedjian A. College students' suggestions for improving sex education in schools beyond 'blah blah blah condoms and STDs'? Sex Educ. 2020:1–15. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2020.1749044. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sadri Damirchi E, Poorzor P, Esmaili Ghazivaloii F. Effectiveness of sexual skills education on sexual attitude and knowledge in married women. J Family Counsel Psychother. 2016;6:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fund UNP, Fund UNP, Fund UNCs, Women UNEfGEatEo, Organization WH, UNESCO. International tchnical guidance on sexuality education: an evidence-informed approach France 2018. 2nd rev. ed. cited 2020 Mar 4. Available from: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000260770 .

- 23.Education EEGoS. Sexuality education – what is it? Sex Educ. 2016;16:427–31. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krebbekx W. What else can sex education do? Logics and effects in classroom practices. Sexualities. 2018;22:1325–41. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thin Zaw PP, McNeil E, Oo K, Liabsuetrakul T, Htay TT. Abstinence-only or comprehensive sex education at Myanmar schools: Preferences and knowledge among students, teachers, parents and policy makers. Sex Educ. 2020:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao P, Yang L, Sa Z, Wang X. Propriety, empowerment and compromise: Challenges in addressing gender among sex educators in China. Sex Educ. 2020:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smerecnik C, Schaalma H, Gerjo K, Meijer S, Poelman J. An exploratory study of muslim adolescents' views on sexuality: Implications for sex education and prevention. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:533. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leung H, Shek DTL, Leung E, Shek EYW. Development of contextually-relevant sexuality education: Lessons from a comprehensive review of adolescent sexuality education across cultures. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:621. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16040621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Refaie Shirpak K, Eftekhar Ardebili H, Mohammad K, Maticka-Tyndale E, Chinichian M, Ramenzankhani A, et al. Developing and testing a sex education program for the female clients of health centers in Iran. Sex Educ. 2007;7:333–49. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Velavan J. A family physician's journey in exploring sexual health perceptions and needs in a boarding school community. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020;9:395–401. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_888_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karimi Moonaghi H, Hasanzadeh F, Shamsoddini S, Emamimoghadam Z, Ebrahimzadeh S. A comparison of face to face and video-based education on attitude related to diet and fluids: Adherence in hemodialysis patients. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2012;17:360–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sargazi M, Mohseni M, Safar-Navade M, Iran-Pour A, Mirzaee M, Jahani Y. Effect of an educational intervention based on the theory of planned behavior on behaviors leading to early diagnosis of breast cancer among women referred to health care centers in Zahedan in 2013. Iran Quart J Breast Dis. 2014;7:45–55. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ranjbar Z, Amiri Zadeh S. An approach to the use of e-learning in education. J Sci Eng Elites. 2018;3:42–9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rogers E, Hemal K, Tembo Z, Mukanu M, Mbizvo M, Bellows B. Comprehensive sexuality education for adolescents in Zambia via the mobile-optimized website TuneMe: A content analysis. Am J Sex Educ. 2020;15:82–98. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown C, Quirk A. Momentum is building to modernize sex education American: Center for American Progress. 2019. Available from: https://cdn.americanprogress.org/content/uploads/2019/05/23052627/Modernize-Sex-Ed_brief11.pdf . Last cited on 2020 Mar 13.

- 36.Fund UNCs. The opportunity for in East Asia and the Pacific digital sexuality education. Bangkok: UNICEF East Asia and Pacific; 2019. cited 2020 Mar 20. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/eap/media/4646/file/Digital%20sexuality%20education.pdf . Last cited on 2020 Mar 20. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mirzaii Najmabadi K, Babazadeh R, Mousavi SA, Mohammad S. Iranian adolescent girls' challenges in accessing sexual and reproductive health information and services. J Health. 2018;8:561–74. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barzegar N, Farjad S, Hosseini N. The effect of teaching model based on multimedia and network on the student learning (Case study: Guidance schools in Iran) Procedia-Soc Behav Sci. 2012;47:1263–7. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park C, Kim D-g, Cho S, Han H-J. Adoption of multimedia technology for learning and gender difference. Comput Hum Behav. 2019;92:288–96. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zulu JM, Blystad A, Haaland MES, Michelo C, Haukanes H, Moland KM. Why teach sexuality education in school? Teacher discretion in implementing comprehensive sexuality education in rural Zambia. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18:116–27. doi: 10.1186/s12939-019-1023-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scott RH, Smith C, Formby E, Hadley A, Hallgarten L, Hoyle A, et al. What and how: Doing good research with young people, digital intimacies, and relationships and sex education. Sex Educ. 2020:1–17. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2020.1732337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chow S-C, Shao J, Wang H. United States of America: Taylor and Francis Group; 2008. Sample Size Calculation in Clinical Research; p. 73. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Behboodi Moghadam Z, Rezaei E, Khaleghi Yalegonbadi F, Montazeri A, Arzaqi SM, Tavakol Z, et al. The effect of sexual health education program on women sexual function in Iran. J Res Health Sci. 2015;15:124–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, et al. The female sexual function index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fakhri A, Mohammadi Zeidi I, Pakpour Haji Agha A, Morshedi H, Mohammad Jafari R, Ghalambor Dezfooli F. Psychometric properties of iranian version of female sexual function index. Jundishapur Sci Med J. 2011;10:345–54. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rahman SM, Angeline RP, Cynthia S, David K, Christopher P, Sankarapandian V, et al. International classification of primary care: An indian experience. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2014;3:362–7. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.148111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Farnam F, Pakgohar M, Mirmohamadali M, Mahmoodi M. Effect of sexual education on sexual health in Iran. Sex Educ. 2008;8:159–68. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mellini L, Poglia Mileti F, Sulstarova B, Villani M, Singy P. HIV sexual risk behaviors and intimate relationships among young Sub-Saharan African immigrants in Switzerland: A brief report. Int J Sex Health. 2019;32:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barikani A, Sarichlow ME, Mohammadi N. The cause of divorce among men and women referred to marriage and legal office in Qazvin, Iran. Glob J Health Sci. 2012;4:184–91. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v4n5p184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bolhari J, Ramezanzadeh F, Abedinia N, Naghizadeh MM, Pahlavani H, Saberi SM. To explore identifying the influencing factors of divorce in Tehran. Iran J Epidemiol. 2012;8:83–93. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mohammadsadeg A, Kalantar-Kosheh SM, Naeimi E. The experience of sexual problems in women seeking divorce and women satisfied with their marriage: A qualitative study. J Qual Res Health Sci. 2018;7:35–47. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ramezani Farkhad A, Saleh Abadi A, Gazlan Tosi J, Safdarzade M, Sadeghi S. 1st ed. Mashhad: Avaye Rana; 2013. Identifying the Effective Factors on Emotional Divorce. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rabathaly PA, Chattu VK. An exploratory study to assess primary care physicians' attitudes toward talking about sexual health with older patients in Trinidad and Tobago. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2019;8:626–33. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_325_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rabathaly P, Chattu VK. Sexual healthcare knowledge, attitudes and practices amongst primary care physicians in Trinidad and Tobago. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2019;8:614–20. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_322_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sabeti F, Tavafian SS, Zarei F. The effect of educational intervention on sexual function of women referred to health center of South of Tehran. Nurs Pract Today. 2018;5:280–9. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nameni F, Yousefzade S, Golmakani N, Najaf Najafi M, Ebrahimi M, Modarres Gharavi M. Evaluating the effect of religious-based sex education on sexual function of married women. Evid Based Care. 2014;4:53–62. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baradaran-Akbarzadeh N, Tafazoli M, Mojahedi M, Mazlom SR. The effect of educational package on sexual function in cold temperament women of reproductive age. J Educ Health Promot. 2018;7:65. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_7_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shams Mofaraheh Z, Botlani Esfahani S, Shahsiah M. The effect of marital counselling on sexual satisfaction of couples. J Hum Health. 2015;1:85–9. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Asadi S, Ghobadi E. Multimedia taching and its effects on learning and retention of english grammar. J Inform Commun Technol. 2012;4:9–17. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jeste DV, Dunn LB, Folsom DP, Zisook D. Multimedia educational aids for improving consumer knowledge about illness management and treatment decisions: A review of randomized controlled trials. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rajabi Naeeni M, Farid M, Tizvir A. A comparative study of the effectiveness of multimedia software and face-to-face education methods on pregnant women's knowledge about danger signs in pregnancy and postpartum. J Educ Community Health. 2015;2:50–7. [Google Scholar]