Abstract

Aim of study:

To assess knowledge, attitude and practice of health care professionals working in Abha primary health care (PHC) centers regarding standard precautions of infection control.

Subjects and Methods:

This cross sectional study included 212 health care professionals in Abha PHC centers. An electronic questionnaire was constructed by the researchers and was used for data collection. It consisted of five parts, i.e., socio-demographic characteristics, knowledge questions about infection control and standard precautions, statements about attitude of participants, practice of health care providers regarding infection control and perceived obstacles against adequate application of standard precautions.

Results:

Most participants were physicians with Bachelor degree (68.9%, and 45.3%, respectively), while 51.9% had an experience less than five years in PHC. About two thirds of PHC centers (60.8%) had a special and separate room for medical waste. Only 55.7% attended training programs on infection control and 72.6% viewed a memo about coronavirus. About one third of participants (31.6%) had poor knowledge about infection control, 88.2% had positive attitude toward infection control policy and procedures, while 49.5% had poor practice level. There were no significant differences in participants' knowledge or attitude according to their socio-demographic characteristics, while their practices were significantly better among those who got a training program about infection control and those who had an experience <5 years in primary care (p = 0.040, and P = 0.032, respectively).

Conclusions:

Health professionals have suboptimal knowledge and practice levels regarding standard precautions of infection control, while most of them have positive attitude. Therefore, it is recommended to enforce their training and to increase the supervision in PHC settings regarding infection control policy and procedures.

Keywords: Infection control, standard precautions, knowledge, attitude and practices, primary health care, health professionals

Introduction

Healthcare professionals (HCPs) are more prone to develop infections through contact with infected body parts, blood and body fluids during their work.[1,2,3] The occupational risk of acquiring respiratory infection to HCPs increases when the measures of infection control are not properly applied.[4,5]

According to WHO, the prevalence of healthcare acquired infection in developed countries is 7.6% while in developing countries is about 10%.[6,7] The WHO has estimated that every year, about 3 million HCPs globally experience exposure to blood-borne Hepatitis C and B and HIV viruses while 2.5% of HIV cases and 40% of HBV and HCV cases among HCPs all over the world are caused by exposures to such infections.[8]

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended using standard precautions by both health care workers and patients.[9] Many studies conclude that adherence to standard precautions measures is fundamental to control healthcare associated infections among health care workers as well as patients.[10,11,12,13]

Despite of standard precautions are nowadays widely promoted in all countries and many relevant guidelines are issued the level of knowledge, attitudes and practice of these precautions for infection control among health care professionals is still substantially suboptimal, and their application is insufficiently reported.[14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]

Studies have reported that failure of HCPs to comply with standard precautions of infection control was associated with lack of knowledge in this area, negative attitudes, and lack of support from both of institutions and patients.[22,23]

Despite the importance of this subject, relevant studies are quite scarce in Aseer Region, Saudi Arabia.

This study aimed to assess knowledge, attitude and practice of health care professionals working in primary health care centers in Abha City, Aseere region, regarding standard precautions of infection control.

Methodology

This Cross-sectional study was conducted among HCP who are working at PHCCs in Abha city, Aseer region, KSA during 2018. In Abha health sector, there was 500 health care providers, who constituted the target population for this study. According to Dahiru et al.,[24] the minimum sample size of participants has been calculated as follows:

where:

- n: Calculated sample size

- Zα/2: The z-value for the selected level of confidence (1-α) = 1.96.

- P: The proportion of those with good knowledge (estimated to be 0.5).

- Q: (1 – P), i.e., 0.5.

- D: The maximum acceptable error = 0.07.

The calculated minimum sample size (n) is:

participants

participants

After taking ethical permission from the Regional Ethical Committee with number (REC-2018-03-40) on 22 May 2018, The study was conducted using an electronic questionnaire for data collection. It was developed and modified from two similar studies which were carried out in Nigeria and Ethiopia.[25,26] REC NO (2018-03-40) dated 22nd May 2018. It was mentioned in methodology section

The questionnaire consisted of the following five parts

Socio-demographic characteristics: Gender, nationality, age, profession, highest qualification and experience in PHC practice.

-

Knowledge regarding infection control and standard precautions (16 questions dealing with sharps and needles, standard precaution application and diseases transmitted by dirty needles and sharps). Total knowledge score was defined as correct response and given one score, while incorrect or incomplete response was given zero. According to the total percent score, participants were classified into two groups:

- Those who achieved ≥60% were considered to have acceptable knowledge (Good).

- Those who achieved <60% were considered to have unacceptable knowledge (Poor).

-

Attitude of participants was measured by seven statements regarding infection control and standard precautions using a five-point Likert scale (ranged between strongly agree to strongly disagree). Attitude was classified into three main groups after calculate the total attitude score (of 35 points):

- Those who achieved ≥60% (i.e., >21 points out of 35 points), were considered to have positive attitude.

- Those who achieved <60% (i.e., less than 21 points out of 35 points) considered to have negative attitude).

- Those who achieved 60% (i.e., 21 points out of 35 points) were considered to have neutral attitude.

-

Practice of health care providers regarding infection control was assessed through six questions using a five-point scale, which ranged between always to never. Participants' practice scores were classified into two main groups after calculating the total practice score (out of 30 points):

- Those who achieved ≥70% (i.e., 21 points or more out of 30 points) were considered to have good practice.

- Those who achieved <70% (i.e., 20 points or less out of 30 points) were considered to have poor practice.

Perceived obstacles against adequate application of standard precautions and infection control were classified into “not important”, “important”, or “very important”.

Data coding, entry and analysis were managed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS ver 23.0). Descriptive statistics were calculated and the appropriate tests of significance (i.e., χ2) were applied accordingly. Statistically significant differences were considered if P values are less than 0.05.

Result

A total of 212 health care providers were participated in this study. Table 1 shows that more than half of participants (59.9%) aged less than 30 years, and 55.7% were males. Most participants were physicians (68.9%), 45.3% had Bachelor degrees, and 51.9% had less than five years' experience in PHC.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of health care professionals, Abha City, KSA, 2018

| Characteristics | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age groups | |

| <30 years | 127 (59.9) |

| 30-40 years | 82 (38.7) |

| >40 years | 3 (1.4) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 118 (55.7) |

| Female | 94 (44.3) |

| Nationality | |

| Saudi | 199 (93.9) |

| Non-Saudi | 13 (6.1) |

| Position | |

| Physician | 146 (68.9) |

| Dentist | 10 (4.7) |

| Nurse | 50 (23.6) |

| Lab technician | 3 (1.4) |

| Dental assistant | 3 (1.4) |

| Qualification | |

| PhD/MD/equivalent | 8 (3.8) |

| Master | 60 (28.3) |

| Bachelor | 96 (45.3) |

| Diploma | 41 (19.3) |

| Others | 7 (3.3) |

| Experience in PHC | |

| <5 years | 110 (51.9) |

| 5-10 years | 64 (30.2) |

| >10 years | 38 (17.9) |

Table 2 shows that about one third of participants (35.8%) were CBAHI (Central Board for Accreditation of Healthcare Institution) accredited, 40.6% of PHC centers had a special room for sterilization, while 38.8% of PHC centers had well trained responsible persons for sterilization. Only 60.8% of PHC centers had a special and separate room for medical waste, while only 55.7% of participants attended training programs on infection control, and 72.6% received a memo about coronavirus. About (27.8%) of participants were exposed to needle stick injury, 25% were exposed to sharp injury, 28.8% were exposed to blood or body splash to their eyes and/or mouth, 86.3% were vaccinated against hepatitis B virus, 57.5% were vaccinated against tetanus, 18.4% discard needles into back bags after use while 75% discard gloves into yellow bags after use.

Table 2.

Profile of primary health care centers and health care professionals regarding infection control, Abha, KSA, 2018

| Characteristics | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| CBAHI accreditation | |

| Yes | 76 (35.8) |

| No | 136 (64.2) |

| Availability of a special room for sterilization in PHC center | |

| Yes | 86 (40.6) |

| No | 126 (59.4) |

| Availability of a special and separate room for medical waste | |

| Yes | 129 (60.8) |

| No | 83 (39.2) |

| Having attended a training program on infection control | |

| Yes | 118 (55.7) |

| No | 94 (44.3) |

| Receiving a memo on MERS-CoV during the last 3 years | |

| Yes | 154 (72.6) |

| No | 58 (27.4) |

| Previous exposure of participants to incidents related to blood-borne infections: | |

| Needle stick injury | 59 (27.8) |

| Sharp injury | 53 (25.0) |

| Blood or body splash to the eye and/or mouth | 61 (28.8) |

| Recent vaccination against hepatitis B infection | 183 (86.3) |

| Vaccination against tetanus (Clostridiumtetani) infection | 122 (57.5) |

| Discarding needles into black bags after use | 39 (18.4) |

| Discarding gloves into yellow bags after use | 159 (75.0) |

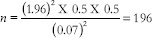

Table 3 shows the knowledge of the participants about infection control. Almost half of participants (45.3%) stated that sharp containers are utilized for used injection needles, 34.9% knew that tetanus-causing agent (Clostridium tetani) can be transmitted via dirty needles and sharps, while 35.8% and 28.3% thought that causative agents of malaria (Plasmodium spp.) and tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) can be transmitted via contaminated needles and sharps. Only 61.4% knew the proper type of isolation for pulmonary tuberculosis patients, and 34.9% thought that there is treatment for those infected with coronavirus. In general, knowledge of 31.6% of participants was lower than 60%, i.e., “poor” knowledge grade, while 68.4% had “good” knowledge grade, as shown in Figure 1.

Table 3.

Knowledge about infection control policy and procedures among primary health care professionals in Abha health sector, KSA, 2018

| Statements | TRUE No. (%) | FALSE No. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Dirty needle and sharp materials can transmit disease causing agents (TRUE) | 206 (97.2) | 6 (2.8) |

| Standard precautions should be practiced on all patients and laboratory specimen serology irrespective of diagnosis (TRUE) | 197 (92.9) | 15 (7.1) |

| Sharps should never be recapped (TRUE) | 171 (80.7) | 41 (19.3) |

| Needles should be bent or broken after use (FALSE) | 51 (24.1) | 161 (75.9) |

| When you have a patient who vomited in dressing room or clinic, the first step in infection control procedure is to isolate infected area (TRUE) | 193 (91.0) | 19 (9.0) |

| Sharp containers are utilized for used injection needles (TRUE) | 96 (45.3) | 116 (54.7) |

| Hepatitis B causing agent can be transmitted with dirty needles and sharps (TRUE) | 201 (94.8) | 11 (5.2) |

| Hepatitis C causing agent can be transmitted with dirty needles and sharps (TRUE) | 198 (93.4) | 14 (6.6) |

| HIV/AIDS causing agent can be transmitted with dirty needles and sharps (TRUE) | 207 (97.6) | 5 (2.4) |

| Tetanus (Clostridium tetani) causing agent can be transmitted with dirty needles and sharps (TRUE) | 74 (34.9) | 138 (65.1) |

| Malaria causing agent (Plasmodium spp) can be transmitted with dirty needles and sharps (FALSE) | 76 (35.8) | 136 (64.2) |

| Tuberculosis causing agent (M. tuberculosis) can be transmitted with dirty needles and sharps (FALSE) | 74 (28.3) | 132 (71.7) |

| Type of isolation with pulmonary tuberculosis is airborne precaution (TRUE) | 130 (61.4) | 82 (38.6) |

| There is treatment for MERS-CoV (coronavirus) (FALSE) | 138 (65.1) | 74 (34.9) |

| The best disinfecting material to clean exposed skin after contamination is soap (TRUE) | 48 (22.6) | 164 (77.4) |

| The appropriate immediate action after pricking finger by I.V. line needle is dressing wound and inform infection control supervisor (TRUE) | 169 (79.7) | 43 (20.3) |

Figure 1.

Knowledge grades of participants about infection control

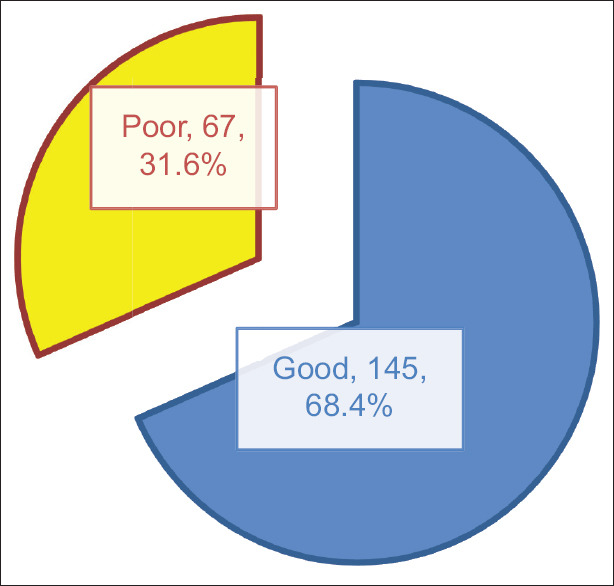

Table 4 depicts participants attitude towards infection control. More than half (58%) strongly agreed while more than one fourth (29%) agreed that standard precautions prevent infection at the health care facility. Most participants disagreed/strongly disagreed regarding no need to wash hands after touching patients' surroundings (13.2% and 68.4%, respectively). Regarding sharps recapping, most participants strongly agreed/agreed that this should never be done (51.4% and 20.8%, respectively). Most participants (65%) disagreed that sharp needles can be bent or broken after use. Most of participants strongly agreed/agreed that using gloves while patient care is a useful in reducing risk of microbial transmission (72%). Most participants strongly agreed/agreed that in absence of standard precautions, health care facilities can be the source of infection and disease epidemics (55.2% and 32.1%, respectively). Most participants strongly agreed/agreed that there is high risk of occupational infection among health workers at their work (21.7% and 37.3%, respectively). Generally, Most participants (88.2%) had positive attitude, 3.3% had neutral attitude, while 8.5% had negative attitude regarding infection control at PHCC as shown in [Figure 2].

Table 4.

Attitude of primary health care professionals toward infection control policy and procedures in Abha health sector, KSA, 2018

| Statements | Strongly agree No. (%) | Agree No. (%) | Neutral No. (%) | Disagree No. (%) | Strongly disagree No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard precautions prevent infection at health care facility | 124 (58.5) | 61 (28.8) | 17 (8.0) | 7 (3.3) | 3 (1.4) |

| There is no need to wash or decontaminate hands after touching patients’ surroundings | 18 (8.5) | 15 (7.1) | 6 (2.8) | 28 (13.2) | 145 (68.4) |

| Sharps should never be recapped | 109 (51.4) | 44 (20.8) | 13 (6.1) | 27 (12.7) | 19 (9.0) |

| Sharp needles can be bent or broken after use | 30 (14.2) | 28 (13.2) | 16 (7.5) | 50 (23.6) | 88 (41.5) |

| Using gloves while patient care is a useful strategy for reducing risk of transmission of microbes | 96 (45.3) | 67 (31.6) | 28 (13.2) | 15 (7.1) | 6 (2.8) |

| In absence of standard precautions, health care facilities can be the source of infection and disease epidemics | 117 (55.2) | 68 (32.1) | 22 (10.4) | 5 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| There is high risk of occupational infection among health workers in my work | 46 (21.7) | 79 (37.3) | 56 (26.4) | 26 (12.3) | 5 (2.4) |

Figure 2.

Attitude grades of participants toward infection control policy and procedures

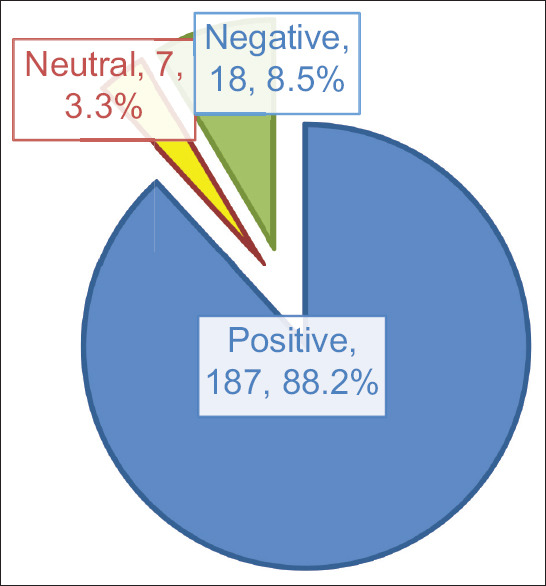

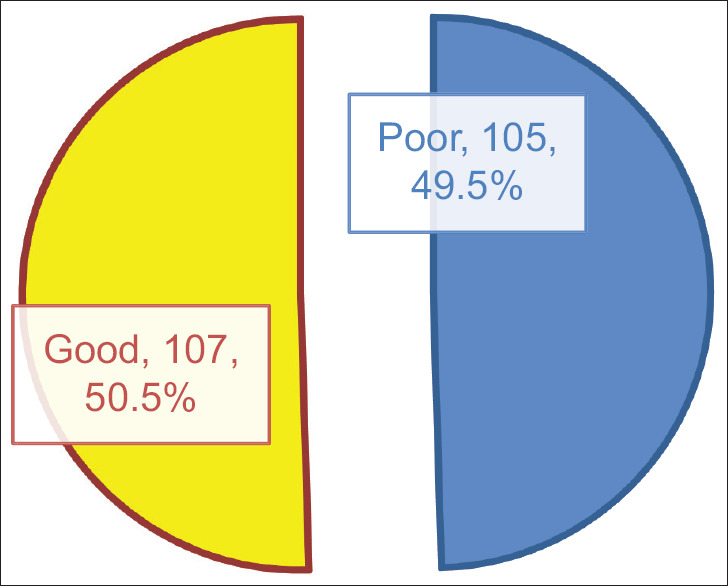

In Table 5, practice regarding infection control among participants is shown. More than half of participants (59.9%) always wash their hands before examining their patients, about one third of participants (34.4%) always recap needles immediately after use, one third of participants (38.7%) always use gloves while examining their patients, 44% always use face masks while examining possibly infective patients, 19% always wear protective goggles during procedures, less than one third (30%) of participants wear medical gowns during procedures. Generally, half of participants (49.5%) had poor practice regarding infection control, as shown in Figure 3.

Table 5.

Practice of participants regarding infection control policy and procedures, Abha health sector, KSA, 2018

| Practices | Always No. (%) | Often No. (%) | Sometimes No. (%) | Rarely No. (%) | Never No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Washing hands before examining patients | 127 (59.9) | 42 (19.8) | 32 (15.1) | 8 (3.8) | 3 (1.4) |

| Recapping needles immediately after use | 73 (34.4) | 29 (13.7) | 21 (9.9) | 12 (5.7) | 77 (36.3) |

| Using gloves while examining all patients | 82 (38.7) | 53 (25.0) | 60 (28.3) | 14 (6.6) | 3 (1.4) |

| Using face mask while examining possibly infective patients | 94 (44.3) | 49 (23.1) | 44 (20.8) | 18 (8.5) | 7 (3.3) |

| Wearing goggles during procedures | 41 (19.3) | 21 (9.9) | 50 (23.6) | 47 (22.2) | 53 (25.0) |

| Wearing medical gown during procedures | 63 (29.7) | 34 (16.0) | 56 (26.4) | 36 (17.0) | 23 (10.8) |

Figure 3.

Practice grades of participants about infection control

Table 6 shows obstacles against infection control policy and procedures. About of half participants (49%) and about one third (34%) believed that lack of training on infection control, is very important or important obstacles, while inadequate hand washing facility was considered as very important or important (93%), lack of personal protection equipment were considered as another important obstacles (93%). Moreover, about 82% considered the lack of guidelines at primary health care centers as important barriers, while 91% of participants consider non-compliance with conditions of infection control by health care providers as very important and important issue. The least important obstacles were overcrowded work place (90%) and shortage of health care workers (83%. Statistical analysis shows that participants' good practice was significantly associated with years of experience in PHC and got a training program about infection control (P value = 0.032, 0.040 respectively).

Table 6.

Obstacles against infection control policy and procedures in Abha health sector, KSA, 2018

| Statements | Not Important No. (%) | Important No. (%) | Very Important No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of training on infection control guidelines | 13 (6.1) | 73 (34.4) | 126 (49.4) |

| Lack of personal protection equipment | 14 (6.6) | 82 (38.7) | 116 (54.7) |

| Inadequate hand washing facility (alcohol solutions) | 15 (7.1) | 71 (33.5) | 126 (59.4) |

| Lack of guidelines at primary health care centers | 17 (8.0) | 90 (42.5) | 105 (49.5) |

| Non-compliance with conditions of infection control by health care providers | 19 (9.0) | 94 (44.3) | 99 (46.7) |

| Overcrowded work place | 22 (10.4) | 107 (50.5) | 83 (39.2) |

| Shortage of health care workers | 37 (17.5) | 105 (49.5) | 70 (33.0) |

Discussion

This study was conducted to assess knowledge, attitude and practice about infection control among primary care professionals. The present study showed that more than 2/3 of participants had good knowledge regarding infection control. There were no statistically significant differences regarding participants' knowledge according to their socio-demographic characteristics or their PHC center profile or previous training on infection control. Compared to previous study that was conducted among Nigerian Health care providers, s, the current knowledge status of participants was lower than that (92–97%).[27] In another study from Nigeria good and fair knowledge among participants was reported as 50% and 44% respectively.[20] In Ethiopia, Yakob et al. showed that all participants had acceptable knowledge about contaminated needles and sharp materials that transmit disease causative agents, while 70.4% knew that gloves and gowns were required for any contact with patients.[26] In Brazil, Oliveria et al. identified a gap between knowledge of standard precautions and the practical applications among physicians.[28]

In hospital-based study conducted in India by Acharya et al., it was reported that health care providers who had good knowledge about infection control standard precautions and transmission of blood-borne pathogens constituted 79.9% and 64.5%, respectively.[29]

These findings are in accordance with those of Acharya et al.,[29] who reported that 77.5% of participants were aware about hepatitis-B vaccine. Moreover, Alice et al.[20] reported that 49.8% and 46.8% of participants had fair and good compliance to standard precautions, respectively.

Ogoina et al.[25] showed that the knowledge scores regarding standard precautions were above 90%, but most health care professionals had poor knowledge about injection safety, while house officers, laboratory scientists and junior nurses had lower compliance compared with experienced doctors and nurses. Yakob et al.[26] reported that 76.3% of respondents thought that they were at risk of acquiring HIV infection during their work.

The present study showed that the participants' attitude toward infection control policy and procedures was positive (88.2%) however, there were no statistically significant differences regarding participants' attitudes according to their socio-demographic characteristics or their PHC center profile.

Practicing infection control precaution was about 60% for wash their hands, 34% recap needles immediately after using, wearing gloves (39%), face masks (44%). These results were lower than that reported by Acharya et al. who found that the washing soiled hands and using gloves were very often practiced by health care professionals were about (73% and 59%, respectively).[29] In Alice et al. study, it was reported that, 43.7% disposed sharp materials in open pails, 67.4% in sharp- and liquid-proof containers without removing syringe while standard blood and body fluid precautions were always practiced by 46.8% of respondents and 76.5% of health care professionals wear gloves while they take blood samples.[20] Yakob et al. found that 68.7% of participants wash their hands before examining their patients and 62.5% recap needle immediately after using them.[26]

The present study found that there was positive impact of training and long experience on practicing infection control among HCP while knowledge and attitude were not affected by such factors. In Acharya et al. study, it was noted that the main sources of information are the refresher training courses to improve practice.[29]

This study found that there were many barriers that stand against practicing policies and procedures of infection control among HCP. They include lack of training, lack of personal protection equipment, lack of guidelines, over-crowding and shortage of HCP. Such obstacles were reported by Amin from AlHassa, KSA.[30]

In order to overcome such barriers, it is mandatory that all HCP should be trained on infection control, to provide health care center with adequate personal protection equipment, guidelines and to monitor HCP regarding compliance with infection control precaution during their daily work.

Conclusion and Recommendations

This study revealed that the majority of primary care professionals do not attend training courses on infection control which affect their knowledge regarding infection control. Despite good attitude toward infection control policy and procedures, almost half of participants have poor practices regarding infection control and standard precautions. There are many obstacles which affected the practice of appropriate infection control guidelines among HCP. Such barriers should be overcome as soon as possible to introduce safe care services for clients attending these health care facilities. Further studies including clinical audits after making appropriate correction of the above mentioned barriers are suggested.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Sreedharan J, Muttappillymyalil J, Venkatramana M. Knowledge about standard precautions among university hospital nurses in the United Arab Emirate. East Med Health J. 2001;17:331–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster TM, Lee MG, McGaw CD, Frankson MA. Knowledge and practice of occupational infection control among health care workers in Jamaica. West Indian Med J. 2010;59:147–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jahan S. Epidemiology of needle stick injuries among health care workers in a secondary care hospital in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2005;25:233–8. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2005.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Health Canada. National Advisory Committee on SARS and public health learning from SARS: Renewal of Public Health in Canada. Health Canada, Ontario. [last accessed on July 23rd, 2020]. Available from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/English/protection/warnings/sars/learning.html .

- 5.Lemass H, McDonnell N, O'Connor N, Rochford S. Infection Prevention and Control for Primary Care in Ireland. A strategy for the control of antimicrobial resistance in Ireland. Healthcare Associated Infections and Antimicrobial Resistance. A Guide for General Practice. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allegranzi B, Bagheri Nejad S, Combescure C, Graafmans W, Attar H, Donaldson L, et al. Burden of endemic health-care associated infection in developing countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011;377:228–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61458-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Report on the Burden of Endemic Health Care-Associated Infection Worldwide. Geneva: WHO; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Report. Reducing risks, promoting healthy life. 2002. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/en . Cited 2018 May21.

- 9.World Health Organization. Update: Universal precautions for prevention of transmission of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, and other blood borne pathogens in health-care settings. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1988;37:377–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L. Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta, Georgia: 2007. Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee, Guideline for isolation precautions: Preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia-Zapata MR-C, Souza ACS, Guimaradães JV, Tipple AFV, Prado MA, García-Zapata MTA. Standard precautions: Knowledge and practice among nursing and medical students in a teaching hospital in Brazil. Int J Infect Control. 2010;6:122–3. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan R, Molassiotis A, Chan E, Chan V, Ho B. Nurses' knowledge of and compliance with universal precautions in an acute care hospital. Int J Nurs Stud. 2002;39:157–63. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(01)00021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jawaid M, Iqbal M, Shahba S. Compliance with standard precautions: A long way ahead. Iran J Public Health. 2009;38:85–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kermode M, Jolley D, Langkham B, Thomas MS, Holmes W, Giffod SM. Compliance with universal/standard precautions among health care workers in rural north India. Am J Infect Control. 2005;33:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2004.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okechukwu EF, Modreshi C. Knowledge and practice of standard precautions in public health facilities in Abuja, Nigeria. Int J Infect Control. 2012;8:10.3396. doi: 10.3396/ijic.v8i3.022.12. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson OE, Asuzu MC, Adebiyi AO. Knowledge and practice of universal precautions among professionals in public and private health facilities in UYO, south Nigeria - A comparative study. Ibom Medical Journal. 2012;5:9–19. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oliveira AC, Cardoso CS, Mascarenhas D. Intensive care unit professionals' knowledge and behavior related to the adoption of contact precautions. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2009;17:625–31. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692009000500005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaziri S, Najafi F, Miri F, Jalalvandi F, Almasi A. Practice of standard precautions among health care workers in a large teaching hospital. Indian J Med Sci. 2008;62:292–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Motamed N, BabaMahmodi F, Khalilian A, Peykanheirati M, Nozari M. Knowledge and practices of health care workers and medical students towards universal precautions in hospitals in Mazandaran Province. East Mediterr Health J. 2006;12:653–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alice TE, Akhere AD, Ikponwonsa O, Grace E. Knowledge and practice of infection control among health workers in a tertiary hospital in Edo state, Nigeria. Direct Res J Health Pharm (DRJHP) 2013;1:20–27. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo Y, He GP, Zhou JW, Luo Y. Factors impacting compliance with standard precautions in nursing, China. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:1106–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sax H, Perneger T, Hugonnet S, Herrault P, Chraiti MN, Pittet D. Knowledge of standard and isolation precautions in a large teaching hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005;26:298–304. doi: 10.1086/502543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Askarian M, Shiraly R, McLaws ML. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of contact precautions among Iranian nurses. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005;33:486–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dahiru T, Aliyu A, Kene TS. Statistics in medical research: Misuse of sampling and sample size determination. Ann Afr Med. 2006;5:158–61. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogoina D, Pondei K, Adetunji B, Chima G, Isichei C, Gidado S. Knowledge, attitude and practice of standard precautions of infection control by hospital workers in two tertiary hospitals in Nigeria. J Infect Prev. 2015;16:16–22. doi: 10.1177/1757177414558957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yakob E, Lamaro T, Henok A. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards infection control measures among Mizan-Aman General Hospital workers, South West Ethiopia. J Community Med Health Educ. 2015;5:1–8. doi: 10.4172/2161-0711.1000370. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adinma ED, Ezeama C, Adinma JI, Asuzu MC. Knowledge and practice of universal precautions against blood borne pathogens amongst house officers and nurses in tertiary health institutions in Southeast Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2009;12:398–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliveria AC, Marziale MHP, Paiva MHRS, Lopes ACS. Knowledge and attitude regarding standard precautions in a Brazilian public emergency service: A cross-sectional study. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2009;43:313–9. doi: 10.1590/s0080-62342009000200009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Acharya AS, Khandekar J, Sharma A, Tilak HR, Kataria A. Awareness and practices of standard precautions for infection control among nurses in a tertiary care hospital. Nurs J India. 2013;104:275–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amin T, Al-Wehedy A. Healthcare providers' knowledge of standard precautions at the primary healthcare level in Saudi Arabia. Infect Dis Health. 2009;14:65–72. [Google Scholar]