Summary

Esophageal neuroendocrine neoplasms (E-NENs) are much rarer than other gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms, the majority showing aggressive behavior with early dissemination and poor prognosis. Among E-NENs, exceptionally rare well differentiated neuroendocrine tumors (E-NET) and more frequent esophageal poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas (E-NEC) and mixed neuroendocrine-non neuroendocrine neoplasms (MiNEN) can be recognized. E-NECs usually exhibit a small cell morphology or mixed small and large cells. Esophageal MiNEN are composed of NEC component admixed with adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma. Gastric (G) NENs encompass a wide spectrum of entities ranging from indolent G-NETs to highly aggressive G-NECs and MiNENs. Among G-NETs, ECL-cell NETs are the most common and, although composed of histamine-producing cells, are a heterogeneous group of neoplastic proliferations showing different clinical and prognostic features depending on the patient’s clinico-pathological background including the morphology of the peri-tumoral mucosa, gastrin serum levels, presence or absence of antral G-cell hyperplasia, and presence or absence of MEN1 syndrome. In general, NET associated with hypergastrinemia show a better outcome than NET not associated with hypergastrinemia. G-NECs and MiNENs are aggressive neoplasms more frequently observed in males and associated with a dismal prognosis.

Key words: neuroendocrine neoplasms, neuroendocrine tumor, neuroendocrine carcinoma, MiNEN, stomach, esophagus

NEUROENDOCRINE NEOPLASMS OF THE ESOPHAGUS

Introduction

Esophageal neuroendocrine neoplasms (E-NENs) are much rarer than other gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors accounting for only 0.04-1%. More than 4000 cases have been described in the international literature 1, where E-NENs represent 0.03-0.05% of all esophageal malignancies 2-4. Their incidence has been increased in the last decades, probably as a secondary effect of improvement in diagnosis and clinician awareness. The majority of E-NENs show an aggressive behavior with early dissemination and poor prognosis depending on size and grade. Unfortunately, the rarity of this neoplasm has not yet permitted the prospective recruitment of patients in clinical trials, in order to establish biological features and the optimal therapeutic regimen.

Clinical presentation

Mean age of E-NEN patients at diagnosis is 66 years with a male prevalence (6:1 ratio). More than 50% of cases originate in the lower third of the esophagus 5. Only a small fraction of patients with E-NEN are asymptomatic and incidentally discovered during endoscopy, while most patients present with dysphagia and weight loss. Less frequent symptoms are pain, hoarseness, and bleeding1. Given the frequent high grade of these neoplasms, carcinoid syndrome is extremely rare, while paraneoplastic syndromes are slightly more frequent.

Less than 1% of E-NENs are well differentiated, while the great majority are high grade poorly differentiated small cell neuroendocrine carcinomas, which present with common lymph node and distant metastases (31-90% of cases) 1,6. Distant metastases are usually located in the liver, lung and bone, while brain metastases are relatively rare7.

Prognostic factors are unclear because of the rarity of this neoplasm and the scarcity of collected data in international literature. Age, disease extent, TNM classification and type of treatment (local +/- systemic) are the main prognostic factors affecting survival.

E-NENs treatment is dependent on histological subtype, grade and stage, but the most effective therapeutic algorithm has not been established. Guidelines suggest, in analogy with lung small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, similar therapeutic protocols including chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgery 7. Recently, a retrospective study analyzing 250 stage I-III E-NEN patients, suggests that patients treated with surgical resection plus chemo and/or radiotherapy show a better 2 year survival than patients without surgical resection of the primary tumour 8. Radical surgery alone provides limited benefits. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the esophagus has a worse prognosis in comparison to esophageal adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma 5.

Histological features

DEFINITION AND TERMINOLOGY

E-NENs are defined as epithelial neoplasms with predominant neuroendocrine differentiation 7. In this category the following are included: esophageal well differentiated neuroendocrine tumors (E-NET), esophageal poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas (E-NEC), and mixed neuroendocrine-non neuroendocrine neoplasms (MiNEN).

E-NETs (grade 1 to 3) are extremely rare; mitotic and Ki67 cut off values for grading are analogous to those applied in other sites. More than 90% of E-NENs are represented by small cell NECs, while a minority by large cell NECs. In a recent case series of 69 consecutive MiNENs, the esophagus and gastro-esophageal junction was identified as the second commonest site of origin (15.9% of cases) after colon-rectum 9. Among MiNEN, the most frequently reported type is the Mixed AdenoNeuroendocrine carcinoma (MANEC).

MICROSCOPIC DESCRIPTION

E-NETs are characterized by a proliferation of uniform, medium sized cells with abundant cytoplasm, ovoid nuclei with dispersed ‘salt and pepper’ chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli, growing in insular, trabecular or cribriform pattern with interposed well-vascularized stroma.

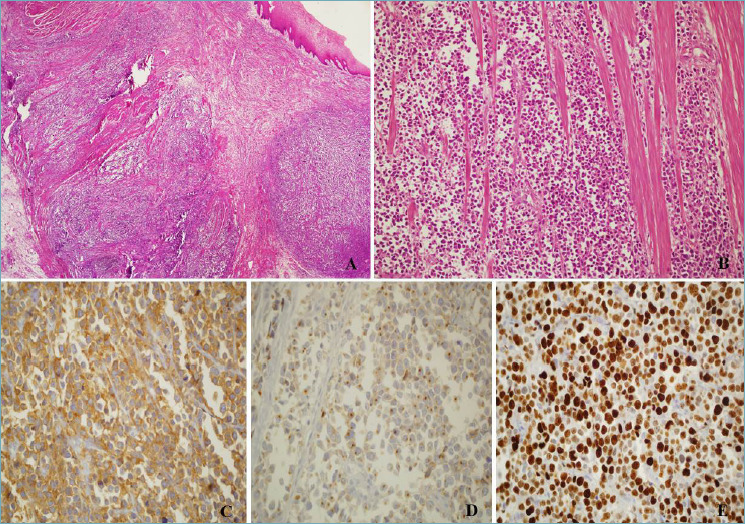

E-NECs are more frequently of the small cell subtype composed of small round, ovoid or spindle-like cells with hyperchromatic nuclei with dense chromatin organized in ample solid insulae or festoons, with multifocal necrosis and frequent mitoses (Fig. 1). A relatively small proportion of E-NECs are composed of large cells with basophilic cytoplasm and marked nuclear atypia with prominent nucleoli.

Figure 1.

(A) Esophageal small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma undermining normal squamous esophageal mucosa; H&E, magnification 4x. (B) Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma infiltrating the muscular wall of the esophagus; H&E, magnification 10x. (C) Diffuse positivity of neoplastic cells for synaptophysin, magnification 20x. (D) Faint, dot-like, positivity for Chromogranin A; magnification 20x. (E) High proliferative index, 80% (Ki-67 stain), magnification 20x.

MiNEN are usually composed of NEC admixed with an adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma (with the two components histologically and immunohistochemically distinguishable). Less than 10 cases of MiNEN composed of NEC and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus are reported in the international literature as case reports 10-11.

Immunohistochemical and molecular markers

Synaptophysin, chromogranin A, and CD56 immunohistochemical stains are used to demonstrate neuroendocrine differentiation and positivity for these markers varies between 60% and 100% of cases with chromogranin A expression usually focal and/or faint in E-NECs.

Hormones can be expressed by neoplastic cells including serotonin, glucagon and gastrin, but in general in NET.

Alcian blu-PAS and cytocheratin 7 can be used to demonstrate and quantify the adenocarcinomatous component in MiNEN, while p63, p40 and cytokeratin 5/6 are used to confirm the squamous component.

No significant data on molecular biology of these tumors is available.

Differential diagnosis

The main differential diagnosis for E-NENs, in particular E-NECs, is with metastases from lung small cell NEC. Clinical history and imaging are of particular effort in this setting, since transcription factor immunohistochemistry is not useful.

Importantly, MiNENs have to been distinguished from carcinoma with focal neuroendocrine differentiation applying two main diagnostic criteria: the recognition of structural features of neuroendocrine morphology (i.e. organoid or solid growth pattern) and the extension of each component (at least 30%).

NEUROENDOCRINE NEOPLASMS OF THE STOMACH

Introduction

NENs of the stomach include small indolent NETs and highly aggressive NECs. They account for about 4% of all NENs with an estimated annual incidence of 0.4 cases/100,000 persons in both USA and Europe 12-13. Rare MiNENs are also observed.

GASTRIC NEUROENDOCRINE TUMORS (NETs)

ECL-cell NETs

Most gastric NETs are composed of ECL-cells and are located in the corpus-fundus (oxyntic) mucosa (Tab. I). They are commonly separated into three different clinical-pathological subtypes with prognosticsignificance, gastrin-dependent type 1 and type 2 of proven ECL-cell nature and gastrin independent type 3 of less obvious cell type characterization 14-17.

Table I.

Clinical-pathological features of gastric NENs.

| M:F ratio | % | Hyper-gastrinemia | Acid secretion | Peritumoral mucosa | ECL-cell proliferations | Grading | Metastasis | 5-year survival | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NET | About 60% | ||||||||

| ECL-cell Type 1 | 1:2.5 | 80-90% of NET | Yes | Low or absent | Atrophic gastritis | Yes | -G1 -G2, rare -G3, exceptional |

1-3% | about 100% |

| ECL-cell Type 2 | 1:1 | 5-7% of NET | Yes | High | Hypertrophic gastropathy | Yes | -G1 -G2, rare |

10-30% | 60-90% |

| Type 3 | 2.8:1 | 10-15% of NET | No | Normal | No specific change | No | -G1, rare -G2 -G3, rare |

50% | <50% |

|

Provisional ECL-cell Type 4 |

Unknown | Unknown | yes | Low or absent | Parietal cell hypertrophy | Yes | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

|

Provisional ECL-cell Type 5 |

1.7:1 | Unknown | yes | Unknown | PPI effects | Yes | -G1 | 15-17% | about 100% |

| G-cell | Unknown | 5% of NET | Possible | Norma or high | Normal or chronic gastritis | No | -G1 | Unknown | about 100% |

| D-cell | Unknown | Unknown | No | Normal | Normal or chronic gastritis | No | -G1 -G2 -G3, rare |

Unknown | about 100% |

| EC-cell | Unknown | Unknown | No | Normal | Normal or chronic gastritis | No | -G1 -G2 -G3, rare |

Unknown | Unknown |

| NEC 1 | 2.1 | 6-20% | No | Normal | Chronic gastritis | No | -G3 | 70% | 10% |

| MiNEN 2 | |||||||||

| ADC/SCC-NEC | 2:1 | 20% | No | Normal | Chronic gastritis | No | see 2 | 55% | 10% |

| ADC/SCC-NET | Unknown | Unknown | No | Normal | Chronic gastritis | No | see 2 | Unknown | Unknown |

NET: neuroendocrine tumor; NEC: neuroendocrine carcinoma; MiNEN: mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasm; ADC: adenocarcinoma; SCC: squamous cell carcinoma; M: male; F: female; PPI: proton pump inhibitor.

1: small and large cell types

2: both the neuroendocrine and the non-neuroendocrine (adenocarcinoma and/or squamous cell carcinoma) components are graded according to WHO 2019.

All gastric NETs are graded into three proliferative grades, according to WHO 2019 correlating with prognosis 16-17. The best prognostic stratification of patients is obtained by coupling the above clinico-pathological classification and the WHO tumor proliferative grade 18.

All gastric NETs are characterized by the expression of chromogranin A, synaptophysin and somatostatin receptor type 2A. ECL-cell NETs are also positive for VMAT2 and histidine decarboxylase (HDC). A few scattered cells may be immunoreactive for serotonin, ghrelin, somatostatin, and alpha-hCG.

Type 1

Type 1 ECL-cell NETs are the most common type, arise in a background of autoimmune chronic atrophic gastritis associated with reduction/lack of acid secretion and consequent antral G-cells hyperplasia and hypergastrinemia. Patients are often female and may have autoantibodies against intrinsic factor and/or parietal cells. Due to the impaired absorption of vitamin B12, a sub-group of patients may also present macrocytic anemia.

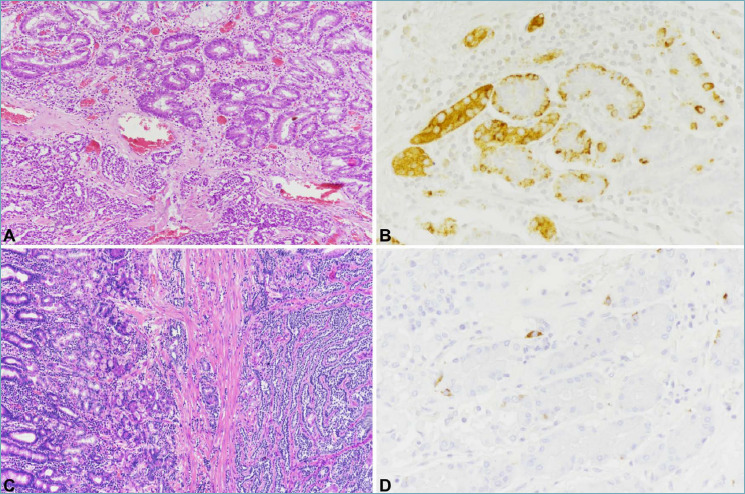

Tumors are generally multiple, small (< 1 cm), limited to the mucosa or submucosa and located in the corpus-fundus. Only larger tumors (> 1 cm) may infiltrate the muscularis propria or beyond. They are composed of well-differentiated cells with monomorphic nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, and fairly abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, arranged in small microlobular and/or trabecular structures (Fig. 2A). Mitotic activity is absent or low and necrosis is lacking. Most cases are G1, but G2 and exceptional G3 cases have been described 17. The surrounding oxyntic mucosa is atrophic, showing ECL-cell hyperplasia and dysplasia (Fig. 2A-B). In the antral mucosa G-cells hyperplasia is the rule.

Figure 2.

Type 1 ECL-cell NET is composed of well-differentiated cells arranged in small microlobular and/or trabecular structures (A, bottom). The peritumoral oxyntic mucosa (A, top) is atrophic with diffuse intestinal metaplasia and shows ECL-cell linear and micronodular hyperplasia, easily detected with chromogranin A immunostaining (B). Type 3 NETs is composed of well differentiated neuroendocrine cells as well, deeply invading the gastric wall (C, right). Peritumoral oxyntic mucosa is normal (C, left) without ECL-cell proliferations (D).

Patients with type 1 ECL-cell NETs have an excellent prognosis with a 10-year survival rate of more than 90%. No significant difference for patient outcome was found between G1 and G2 cases, suggesting tumor grade may not be the most important predictor in this subgroup 17. The risk for lymph node metastasis correlates with tumor size and deep wall invasion 17.

Type 2

Type 2 ECL-cell NETs account for about 5-7% of ECL-cell NETs and are observed in patients with MEN1 syndrome, without gender predilection. Tumors are generally multiple, measure < 2 cm and arise in hypertrophic-hypersecretory oxyntic mucosa due to gastrin stimulation. Hyperplastic and dysplastic ECL-cell proliferations are observed in the hypertrophic peritumoral mucosa. Hypergastrinemia is caused by a duodenal or, more rarely, a pancreatic gastrinoma. Patients with sporadic gastrinomas do not develop ECL-cell NETs 19, suggesting the MEN1 defect is required for ECL-cell transformation upon gastrin stimulus 20.

Type 3

Type 3 NETs were traditionally considered ECL-cell NETs. However, since histamine production or typical “ECL-type” secretory granules were not demonstrated in all cases, the designation ECL-cell has been removed in the last WHO classification 21. Type 3 NETs account for about 10-15% of gastric NETs and are more frequent in males than in females. Patients do not associate with hypergastrinemia and/or chronic autoimmune atrophic gastritis and may present symptoms related to tumor growth or metastatic dissemination.

Type 3 NETs are solitary and large lesions composed of well differentiated neuroendocrine cells frequently invading the muscularis propria and the sub-serosa (Fig. 2C). Lymph node and distant metastases are not rare. Most cases are G1 or G2, but G3 NETs were described 16. The diagnosis on small biopsy may be a challenge and is achieved by evaluating the peritumoral mucosa which is usually normal or with minimal gastritis (Fig. 2C-D).

The prognosis of type 3 NETs depends on grade and stage with a 10-year disease-specific survival of about 50% 16-17.

Provisional types

Two additional types have recently been proposed, which are worth being considered while awaiting full clinico-pathologic and/or biochemical characterization.

Provisional Type 4 ECL-cell NETs were described in association with achlorhydria, parietal cell hyperplasia and hypergastrinemia. The gastric mucosa shows dilated oxyntic glands with inspissated secretory luminal material and parietal cells with often vacuolated abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm 22-23. The pathogenesis was linked to inappropriate acid secretion from functional defective parietal cells with mutated gastric proton pump α-subunit, antral-G cell hyperplasia and hypergastrinemia. Only two cases were carefully documented, one of which with lymph node metastases 23.

Provisional Type 5 ECL-cell NETs arising in moderate hypergastrinemic patients treated continuously for a long time (at least one year) with PPI, without autoimmune chronic atrophic gastritis, gastrinoma, and MEN1 syndrome have recently been described 24. Since these tumors are associated with a normal or slightly hyperplastic peri-tumoral oxyntic mucosa, they may mimic in part type 3 NETs, from which they need to be differentiated due to the different prognosis 25. Indeed, this ECL-cell NET subtype shows a better behavior that type 3 NET not requiring an aggressive surgical approach. Tumors are slightly more frequent in males. Lymph node metastases have been described in about 15% of patients, but prognosis is excellent.

Commentary on provisional types: a report on a familial cluster of classical Type 1 ECL-cell tumors demonstrated a high incidence of mutation of the ATP4A proton pump gene 26. Although this heritable condition defined a specific clinical profile (younger age of onset, higher malignancy and iron deficiency anemia), it represents a proof of concept that gastrin dependent ECL-cell NETs may result from the combination of both epigenetic and predisposing genetic factors, either known (MEN1 syndrome genetic changes) or presently unknown. This possibility requires careful investigation, especially concerning provisional types.

Other gastric NETs

G-cell, D-cell, and EC-cell NETs are rare (about 5% of all gastric NENs) and usually non-functioning. Gastrin-producing G-cell NETs are generally small, located in proximity of the pylorus and are composed of well-differentiated neuroendocrine cells forming thin trabeculae or gyriform structures. Neoplastic cells are positive for neuroendocrine markers, somatostatin receptor (subtype 2A), and gastrin. Somatostatin-producing D-cell NETs are extremely rare and located in the antrum. They are composed of well-differentiated monomorphic cells positive for chromogranin A, synaptophysin and somatostatin. In general, both G-cell and D-cell NETs are indolent with excellent prognosis, even in the presence of deep wall invasion or lymph node metastasis 13. EC-cell NETs may arise in any part of the stomach and are composed of well-differentiated cells with intense eosinophilic cytoplasm in nests with a peripheral palisading. Tumor cells are positive for general neuroendocrine markers, serotonin, CDX2, and somatostatin receptor subtype 2A.

GASTRIC NEUROENDOCRINE CARCINOMA (NEC)

Gastric NECs account for about 6-21% of gastric NENs and usually arise in the antral or cardial regions. Males are more frequently affected (male/female ratio of 2:1) with 65 years (range 41-76 years). Patients generally present non-specific symptoms due to local growth or metastatic dissemination. Usually large lesions, gastric NECs are small and large cell types at histology. Neoplastic cells are positive for synaptophysin while chromogranin A is either faint or expressed with a peripheral or para-nuclear dot-like pattern. NECs may also express nuclear TTF1 or CDX2. Patients’ prognosis is dismal prognosis with survival usually measured in months.

GASTRIC MIXED NEUROENDOCRINE-NON NEUROENDOCRINE NEOPLASM (MiNEN)

MiNEN are usually large, polypoid, ulcerating or stenotic lesions. The neuroendocrine component is often a NEC (small or large cell subtypes) and only rarely a NET. The non-neuroendocrine component is generally an adenocarcinoma or, rarely, a squamous cell carcinoma especially when in the cardial region. MiNENs composed by adenocarcinoma and NEC (MANEC) account for about 20% of all digestive MiNENs 27. Patients have a poor prognosis and the Ki67 proliferative index of the NEC component correlates with prognosis 27.

Rare cases of adenoma associated with NET have also been reported 28.

Figures and tables

References

- 1.Giannetta E, Guarnotta V, Rota F, et al. A rare rarity: neuroendocrine tumor of the esophagus. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2019;137:92-107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2019.02.012 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2019.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babu Kanakasetty G, Dasappa L, Lakshmaiah KC, et al. Clinicopathological profile of pure neuroendocrine neoplasms of the esophagus: a south indian center experience. J Oncol 2016;2016:2402417. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/2402417 10.1155/2016/2402417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yun JP, Zhang MF, Hou JH, et al. Primary small cell carcinoma of the esophagus: clinicopathological and immunohistochemical features of 21 cases. BMC Cancer 2007;7:38. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-7-38 10.1186/1471-2407-7-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang Q, Wu H, Nie L, et al. Primary high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma of the esophagus: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 42 resection cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2013;37:467-83. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e31826d2639 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31826d2639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai W, Ge W, Yuan Y, et al. A 10-year Population-based study of the differences between NECs and carcinomas of the esophagus in terms of clinicopathology and survival. J Cancer 2019;10:1520-1527. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.29483 10.7150/jca.29483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egashira A, Morita M, Kumagai R, et al. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the esophagus: clinicopathological and immunohistochemical features of 14 cases. PLoS One 2017;12:e0173501. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0173501 10.1371/journal.pone.0173501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ilett EE, Langer SW, Olsen IH, et al. Neuroendocrine Carcinomas of the gastroenteropancreatic system: a comprehensive review. Diagnostics 2015;5:119-76. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics5020119 10.3390/diagnostics5020119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erdem S, Troxler E, Warschkow R, et al. Is there a role for surgery in patients with Neuroendocrine Tumors of the esophagus? A contemporary view from the NCDB. Ann Surg Oncol 2020;27:671-80. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-019-07847-1 10.1245/s10434-019-07847-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frizziero M, Wang X, Chakrabarty B, et al. Retrospective study on mixed neuroendocrine non-neuroendocrine neoplasms from five European centres. World J Gastroenterol 2019;25:5991-6005. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i39.5991 10.3748/wjg.v25.i39.5991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dasari CS, Ozlem U, Kohli DR. Composite neuroendocrine and squamous cell tumor of the esophagus. ACG Case Rep J 2019;6:e00248. https://doi.org/10.14309/crj.0000000000000248 10.14309/crj.0000000000000248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang L, Sun X, Zou Y, Meng X. Small cell type neuroendocrine carcinoma colliding with squamous cell carcinoma at esophagus. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2014;7,1792-5 eCollection 2014. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dasari A, Shen C, Halperin D, et al. Trends in the incidence, prevalence, and survival outcomes in patients with neuroendocrine tumors in the United States. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:1335-42. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0589 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.La Rosa S, Vanoli A. Gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms and related precursors lesions. J Clin Pathol 2014;67:938-48. 10.1136/jclinpath-2014-202515 10.1136/jclinpath-2014-202515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rindi G, Luinetti O, Cornaggia M, et al. Three subtypes of gastric argyrophil carcinoid and the gastric neuroendocrine carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study. Gastroenterology 1993;104:994-1006. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(93)90266-f 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90266-f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rindi G, Azzoni C, La Rosa S, et al. ECL cell tumor and poorly differentiated endocrine carcinoma of the stomach: prognostic evaluation by pathological analysis. Gastroenterology 1999;116:532-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70174-5 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70174-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.La Rosa S, Inzani F, Vanoli A, et al. Histologic characterization and improved prognostic evaluation of 209 gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms. Hum Pathol 2011;42:1373-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2011.01.018 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vanoli A, La Rosa S, Miceli E, et al. Prognostic evaluations tailored to specific gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms: analysis of 200 cases with extended follow-up. Neuroendocrinology 2018;107:114-26. https://doi.org/10.1159/000489902 10.1159/000489902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klöppel G, La Rosa S. Ki67 labeling index: assessment and prognostic role in gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Virchows Arch 2018;472:341-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-017-2258-0 10.1007/s00428-017-2258-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peghini PL, Annibale B, Azzoni C, et al. Effect of chronic hypergastrinemia on human enterochromaffin-like cells: insights from patients with sporadic gastrinomas. Gastroenterology 2002;123:68-85. https://doi.org/10.1053/gast.2002.34231 10.1053/gast.2002.34231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berna MJ, Annibale B, Marignani M, et al. A prospective study of gastric carcinoids and enterochromaffin-like cell changes in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: identification of risk factors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:1582-91. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2007-2279 10.1210/jc.2007-2279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.La Rosa S, Rindi G, Solcia E, Tang LH. Gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms. In: WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board eds. WHO classification of tumours. 5th ed. Digestive system tumours. Lyon: IARC press; 2019, pp. 104-109. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ooi A, Ota M, Katsuda S, et al. An unusual case of multiple gastric carcinoids associated with diffuse endocrine cell hyperplasia and parietal cell hypertrophy. Endocr Pathol 1995;6:229-237. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02739887 10.1007/BF02739887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abraham SC, Carney JA, Ooi A, et al. Achlorhydria, parietal cell hyperplasia, and multiple gastric carcinoids: a new disorder. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:969-75. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pas.0000163363.86099.9f 10.1097/01.pas.0000163363.86099.9f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trinh VQ, Shi C, Ma C. Gastric neuroendocrine tumors from long-term proton pump inhibitor users are indolent tumors with good prognosis. Histopathology 2020;77:865-76. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.14220 10.1111/his.14220. Epub 2020 Sep 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.La Rosa S, Solcia E. New insights into the classification of gastric neuroendocrine tumours expanding the spectrum of ECL-cell tumours related to hypergastrinemia. Histopathology 2020;77:862-64. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.14226 10.1111/his.14226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calvete O, Reyes J, Zuñiga S, et al. Exome sequencing identifies ATP4A gene as responsible of an atypical familial type I gastric neuroendocrine tumour. Human Molecular Genetics 2015;24:2914-22. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddv054 10.1093/hmg/ddv054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Milione M, Maisonneuve P, Pellegrinelli A, et al. Ki67 proliferative index of the neuroendocrine component drives MANEC prognosis. Endocr Relat Cancer 2018;25:583-593. https://doi.org/10.1530/ERC-17-0557 10.1530/ERC-17-0557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.La Rosa S, Uccella S, Molinari F, et al. Mixed adenoma well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor (MANET) of the digestive system: an indolent subtype of mixed neuroendocrine-nonneuroendocrine neoplasm (MiNEN). Am J Surg Pathol 2018;42:1503-12. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000001123 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]