Abstract

Objectives:

The co-occurrence of different classes of population-level stressors, such as social unrest and public health crises, is common in contemporary societies. Yet, few studies explored their combined mental health impact. The aim of this study was to examine the impact of repeated exposure to social unrest-related traumatic events (TEs), coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic-related events (PEs), and stressful life events (SLEs) on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depressive symptoms, and the potential mediating role of event-based rumination (rumination of TEs-related anger, injustice, guilt, and insecurity) between TEs and PTSD symptoms.

Methods:

Community members in Hong Kong who had utilized a screening tool for PTSD and depressive symptoms were invited to complete a survey on exposure to stressful events and event-based rumination.

Results:

A total of 10,110 individuals completed the survey. Hierarchical regression analysis showed that rumination, TEs, and SLEs were among the significant predictors for PTSD symptoms (all P < 0.001), accounting for 32% of the variance. For depression, rumination, SLEs, and PEs were among the significant predictors (all P < 0.001), explaining 24.9% of the variance. Two-way analysis of variance of different recent and prior TEs showed significant dose-effect relationships. The effect of recent TEs on PTSD symptoms was potentiated by prior TEs (P = 0.005). COVID-19 PEs and prior TEs additively contributed to PTSD symptoms, with no significant interaction (P = 0.94). Meanwhile, recent TEs were also potentiated by SLEs (P = 0.002). The effects of TEs on PTSD symptoms were mediated by rumination (β = 0.38, standard error = 0.01, 95% confidence interval: 0.36 to 0.41), with 40.4% of the total effect explained. All 4 rumination subtypes were significant mediators.

Conclusions:

Prior and ongoing TEs, PEs, and SLEs cumulatively exacerbated PTSD and depressive symptoms. The role of event-based rumination and their interventions should be prioritized for future research.

Keywords: post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, rumination, social unrest, pandemic, stressful life events, cumulative trauma

Abstract

Objectifs:

La cooccurrence de différentes classes de stresseurs au niveau de la population, comme l’agitation sociale et les crises de santé publique, est commune dans les sociétés contemporaines. Et pourtant, peu d’études ont exploré l’impact combiné qu’elles ont sur la santé mentale. La présente étude visait à examiner l’impact de l’exposition répétée aux événements traumatiques (ET) liés à l’agitation sociale, aux événements liés à la pandémie de la COVID-19 (EP), et aux événements de la vie stressants (EVS) sur le trouble de stress post-traumatique (TSPT) et les symptômes dépressifs, et le rôle de médiation possible de la rumination basée sur les événements (rumination de la colère liée aux ET, de l’injustice, de la culpabilité, et de l’insécurité) entre les ET et les symptômes du TSPT.

Méthodes:

Les membres de la communauté de Hong Kong qui avaient utilisé un instrument de dépistage du TSPT et des symptômes dépressifs ont été invités à répondre à un sondage sur l’exposition aux événements stressants et aux ruminations basées sur les événements.

Résultats:

Dix mille cent dix personnes ont répondu au sondage. L’analyse de régression hiérarchique a indiqué que la rumination, les ET, et les EVS étaient parmi les prédicteurs significatifs des symptômes du TSPT (all p < 0,001), représentant 32% de la variance. Pour la dépression, la rumination, les EVS et les EP étaient parmi les prédicteurs significatifs (all p < 0,001), expliquant 24,9% de la variance. Une analyse de variance à 2 facteurs de différents ET récents et antérieurs a montré des relations dose-effet significatives. L’effet d’ET récents sur les symptômes du TSPT était potentialisé par les ET antérieurs (p = 0,005). Les EP de la COVID-19 et les ET antérieurs s’additionnaient et contribuaient aux symptômes du TSPT, sans interaction significative (p = 0,94). Entre-temps, les ET récents étaient aussi potentialisés par les EVS (p = 0,002). Les effets des ET sur les symptômes du TSPT étaient véhiculés par rumination (β = 0,38; ET = 0,01; IC à 95% 0,36 à 0,41), 40,4% de l’effet total étant expliqué.

Conclusions:

Les ET, EP et EVS antérieurs et actuels ont cumulativement exacerbé le TSPT et les symptômes dépressifs. Le rôle de la rumination basée sur les événements et de leurs interventions devrait être prioritaire pour la future recherche.

Introduction

The co-occurrence of social unrest and public health crisis in the same population is increasingly observed in many global societies.1–3 They have been separately reported to contribute to increased prevalence of mental disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression.4–6 However, there remains a dearth of empirical information on how these classes of co-occurring stressful events collectively interact to disrupt mental health.7

Traumatic events (TEs) have largely been studied in the context of PTSD, which typically consist of fear-inducing events8 that appear to differentiate from depressogenic stressful life events (SLEs).9 Most studies tended to focus on single classes of population-level stressful events (e.g., only TEs) and rarely addressed multiple co-occurring classes of events.

Since June 2019, a series of local protests escalated into months of police-civilian confrontations in Hong Kong, involving tear gas, bean bag rounds, rubber bullets, and Molotov cocktails.10 Thousands of arrests have since been made.11 Substantial mental distress has already been observed during the initial months.3

The subsequent outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) led to widespread panic.12 Feelings of helplessness and sense of insecurity were reinforced by memories of the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic13 and the eroded trust in government.14 During this period, individuals were exposed to not only streams of TEs but also COVID-19 pandemic-related events (PEs) and other personal SLEs. How these classes of events interact to engender symptoms has seldom been investigated in the same sample.

A potential mechanism linking these events to psychopathology is rumination,15 which has been considered a precursor for depression and PTSD.16,17 Nonetheless, most previous studies predominantly focused on depressive rumination.15 Few studied rumination relating to external societal situations. Initial evidence has suggested that in response to conflict trauma, injustice rumination can have substantial long-term impact.18

Collecting information on mental health while population-level stressful events are still ongoing is important for informing timely intervention strategies. Nevertheless, timely access to individuals’ experiences in situ in crisis situations is often difficult because of the multiple physical, psychological, and administrative barriers (e.g., COVID-19 social distancing, eroded trust in institutions and authorities).19

Using a large community sample, the following hypotheses were tested: first, responses to recent TEs (i.e., past 1 month) will be cumulatively affected by experienced in the earlier months during the same protracted period (e.g., over 1 month but within the same year); second, the impact of TEs on symptoms would be potentiated by COVID-19-related PEs and personal SLEs; third, TEs will be more associated with PTSD symptoms, while PEs and SLEs will be more associated with depressive symptoms; and forth, event-based rumination will mediate the impact of TEs on PTSD symptoms.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

Data were collected from a mental health survey with an Internet-based tool between February 21, 2020, and March 6, 2020. The survey was developed after in-depth discussions and pilot testing with members of the local community and mental health professionals.

Participants were recruited among individuals who visited an online self-help mental health tool. The tool offered a means for self-evaluation and provided help-seeking advice for those with high symptom levels and self-help tips for those with lower symptom levels. During the data collection period, 20,740 individuals utilized the tool for PTSD and depressive symptom screening. They were invited to participate in the survey on exposure to TEs, PEs, SLEs, rumination, and other risk and protective factors. Participants were told they could remain anonymous. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster.

Procedure

Demographic information included gender (female, male, others), age (<25 years, 25 to 44 years, ≥45 years), education level (primary education or below, secondary education, bachelor’s degree or above), employment status (full-time, unemployed, student), and past psychiatric history.

We assessed PTSD symptoms with the Trauma Screening Questionnaire (TSQ),20 a 10-item scale using dichotomous responses. A score of 6 or above suggests high risk for PTSD. The TSQ has demonstrated good internal consistency in an epidemiological sample in Hong Kong (α = 0.93).21 Depressive symptoms were assessed with the 7-item depression subscale of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-D)22 on a 4-point Likert scale. A score of 10 to 20 signifies mild to moderate symptoms and 21 or above signifies severe or extremely severe symptoms. The Chinese version of the DASS-D has been reported to have good reliability (α = 0.82).23 Participants were divided into groups based on their TSQ and DASS-D scores. In the current study, the Cronbach’s α coefficients for TSQ and DASS-D were 0.92 and 0.88, respectively.

Three tailor-made checklists adapted to the current context (Table 1) were used to assess exposure to TEs (8 items), PEs (6 items), and SLEs (10 items). For each TE reported, participants were further asked (i) whether the event was experienced once or more than once, (ii) when the TE (or the most severe experience of the same TE) was experienced (over 3 months, within 1 to 3 months, recent 1 month), and (iii) the associated distress level (4-point Likert scale). The events were grouped into TEs experienced over 1 month (prior TEs) for comparison with TEs within the recent month (recent TEs). As media exposure to TEs has been suggested to play an important role in acute stress reactions,24 2 items on media TEs exposure were also included (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics and Types of Population- and Individual-level Stressful Events Reported.

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Gender | |

| Female | 7,458 (73.8) |

| Male | 2,588 (25.6) |

| Others | 64 (0.6) |

| Age group | |

| <25 | 4,906 (48.5) |

| 25 to 44 | 4,643 (45.9) |

| ≥45 | 561 (5.5) |

| Education | |

| Primary education or below | 12 (0.1) |

| Secondary education | 3,514 (34.8) |

| Bachelor’s degree or above | 6,501 (64.3) |

| Occupation | |

| Full-time employment | 4919 (48.7) |

| Unemployed | 878 (8.7) |

| Student | 3,723 (36.8) |

| Past history | |

| Past psychiatric history | |

| Yes | 1,845 (18.2) |

| Past adversity (before the age of 10) | |

| Parents absent from home continuously for a significant period of time | 3,270 (32.3) |

| Bullied at school | 2,564 (25.4) |

| Loss of a parent | 589 (5.8) |

| Physical abuse | 1,166 (11.5) |

| Emotional abuse | 2,336 (23.1) |

| Sexual abuse | 220 (2.2) |

| Others | 258 (2.6) |

| Any past adversity | 5,758 (57) |

| Precipitating events | |

| Social unrest-related traumatic events (TEs) | |

| Personally experienced physical attacks | 437 (4.3) |

| Experienced crowd dispersal by the use of force | 2,829 (28.0) |

| Experienced sexual violence | 49 (0.5) |

| Experienced arrest or detention | 300 (3.0%) |

| Experienced targeted verbal assaults/threats | 2,295 (22.7) |

| Witnessed (in person) violent attacks on others | 3,717 (36.8) |

| Witnessed (online/in person) actions such as road blockages, property destruction, and things being set on fire | 7,651 (75.7) |

| Witnessed (online) others get violently attacked | 9,154 (90.5) |

| COVID-19 pandemic-related events (PEs) | |

| Lack of protective gear | 5,456 (54.0) |

| Working in high-risk environments | 1,217 (12) |

| Placed under quarantine | 279 (2.8) |

| Family members or significant others affected | 94 (0.9) |

| Feel lost about the future | 6,600 (65.3) |

| Others | 333 (3.3) |

| Personal stressful life events (SLEs) | |

| Conflict with family | 4,869 (48.2) |

| Conflict with friends | 2,613 (25.8) |

| Being bullied | 316 (3.1) |

| Being abused (physical, emotional, sexual) | 73 (0.7) |

| Self-initiated termination of employment/ studies | 511 (5.1) |

| Dismissed from job/expelled from school | 334 (3.3) |

| Serious physical health conditions | 832 (8.2) |

| Passing away of a significant other | 637 (6.3) |

| Experienced legal actions or being charged | 318 (3.1) |

| Others | 833 (8.2) |

Note. Data are presented in the form of n (%). COVID-2019 = coronavirus disease 2019.

Four common psychological reactions during this period identified through interviews, namely anger, injustice, guilt, and insecurity, were assessed using 2 items for each reaction with 4-point Likert scales, where the first addressed intensity of the reaction (“not at all,” “a little,” “quite a bit,” “totally”), and the second addressed frequency of rumination (“none,” “infrequently,” “frequently,” “nearly all the time”). Rumination was defined as frequent repetitive thoughts over these psychological reactions that caused disruptions to other tasks. A composite rumination score was derived using the sum of the 4 frequency-based rumination items.

Eleven panel members (5 experts and 6 laypersons) were consulted to assess the content and face validity of the rumination measures. All 8 items (intensity and frequency for each psychological reactions) met the criteria of (i) content validity ratio ≥0.62 (range: 0.64 to 1.00),25 (ii) item-level content validity index >0.79 (range: 0.91 to 1.00),26 and (iii) impact score ≥1.5 (range: 3.42 to 4.73).27 The recommended standard of scale-level content validity index ≥0.9026 was also met (Supplementary Material S1). The internal consistency of the composite rumination items was good (α = 0.84).

The extent of smartphone use was assessed with 3 survey items that considered its impact on social and occupational functioning, cravings for smartphone use, and its consumption of sleep and leisure time (4-point Likert scale: “completely agree,” “agree,” “disagree,” and “completely disagree”).

Other risk and protective factors were also assessed, including past adversity (Table 1), resilience, Internet use, relationship with family and friends, financial worries, personal hope, positive reappraisal, and sleep and exercise patterns. Some of these data will be reported elsewhere.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 25.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, New York). Mediation analyses were carried out with PROCESS.28 All tests were 2-tailed, with a significance level of P < 0.05.

Descriptive statistics were generated for gender, age, education level, occupation, past psychiatric history, past adversity, symptoms, precipitating events, and rumination. The confounding influence of demographic variables on symptoms was explored using independent t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post-hoc analysis using Tukey’s Honestly significant difference test. Three identified confounding variables (gender, age, and past psychiatric history) were controlled for in subsequent analyses, including chi-square test to test for associations between PTSD and depressive symptoms, one-way ANOVA to compare PTSD symptom levels between different TEs exposure groups (no TEs, indirect TEs only, direct TEs), and Pearson’s correlation to assess the relationships between potential and symptoms.

To avoid possible content overlaps between rumination and a potentially related item in the TSQ (item 1: “Upsetting thoughts or memories about the event”), this item was removed in an additional correlation analysis and the subsequent regression analysis. Likewise, item 6 of the DASS-D (“I felt I wasn’t worth much as a person”) was removed in similar supplementary analyses (Supplementary Material S3 to S4).

Two multiple hierarchical regression models were applied to identify significant predictors for PTSD and depressive symptoms, respectively. Variables were sequentially entered in the following blocks: (1) gender, age, and past psychiatric history (to control for confounders); (2) past adversity (to confirm its relationship with symptoms as established in previous studies); (3) TEs, PEs, and SLEs; and (4) composite rumination.

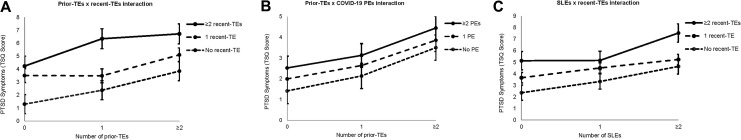

Recent TEs, prior TEs, PEs, and SLEs were each categorized into (i) no event, (ii) 1 event, and (iii) 2 or more events (Table 2). We explored the interactions between recent and prior events in impacting PTSD and depressive symptoms by testing the following event combinations using 2-way ANOVAs: (i) recent TEs (within 1 month) × prior TEs (over 1 month), (ii) PEs × prior TEs, (iii) recent-TEs × SLEs. Significant main effect of recent and prior events without interaction would indicates an additive linear relationship between the 2 event classes, while a significant interaction would indicates a potentiating effect. Further exploration of the recent TEs × prior TEs interaction was performed with post-hoc analyses between (1) TEs ≥ 2 vs TEs = 0, (2) TEs = 1 vs TEs = 0, and (3) TEs ≥ 2 vs TEs = 1 (Supplementary Material S7).

Table 2.

Number of Events Reported for TEs, PEs, and SLEs.

| Event class | Number of events reported | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| None | 1 Event | ≥2 Events | |

| Prior TEs (>1 month) | 577 (5.7) | 2,251 (22.3) | 7,282 (72) |

| Recent TEs (≤1 month) | 8,305 (82.1) | 1,430 (14.1) | 375 (3.7) |

| Total TEs | 409 (4) | 1,800 (17.8) | 7,901 (78.2) |

| PEs | 1,543 (15.3) | 3,963 (39.2) | 4,604 (45.5) |

| SLEs | 2,847 (28.2) | 4,306 (42.6) | 2,957 (29.2) |

Note. Data are presented in the form of n (%). PEs = COVID-19 pandemic-related events; SLEs = personal stressful life events; TEs = social unrest-related traumatic events.

Mediation analysis was performed to test if composite rumination mediated between TEs and PTSD symptoms. The 4 rumination subtypes (anger, injustice, guilt, and insecurity) were then simultaneously entered into a multiple mediation model29 to examine their independent contributions to the relationship, controlling for other rumination subtypes. Mediation indirect effects were tested using bootstrapping procedures with a size of 10,000 samples, with a confidence interval of 95% (95% CI).

Furthermore, a hierarchical regression analysis and 2-way ANOVA controlling for the extent of smartphone use were conducted to examine the role of smartphone use in the relationship between exposure and PTSD symptoms and the potential recent TEs × prior TEs interaction effects (Supplementary Material S5). Predictors of PTSD and depressive symptoms were also further explored within each symptom severity subgroup using separate hierarchical regression models (Supplementary Material S6).

Results

A total of 10,110 participants completed the survey. Table 1 presents the sample characteristics. Compared with those who did not participate (n = 10,630), participants of this study were more likely to be females, χ2(2, N = 20,740) = 168.78, P < 0.01; be younger, χ2(2, N = 20,740) = 44.10, P < 0.01; and have a past psychiatric history, χ2(1, N = 20,740) = 45.36, P < 0.01.

Symptoms and Stress Exposure

High levels of depressive symptoms were observed (mean = 19.4, standard deviation [SD] = 10.3): 44.3% (n = 4,477) scored between 10 and 20 (mild-to-moderate) and 39.8% (n = 4,027) scored 21 or above (severe) in DASS-D. For PTSD symptoms, 38% (n = 3,805) scored 6 or above in the TSQ (mean = 3.7, SD = 3.6). Nearly all of those with higher PTSD risk reported at least 1 core symptom of recurrent memories or recurrent distressing dreams (n = 3,604; 94.7%). High PTSD tended to co-occur with high depressive symptoms: 60.8% (n = 2,314) of those with high PTSD also had severe depressive symptoms (DASS-D ≥ 21) compared with 27.2% (n = 1,713) in those with fewer PTSD symptoms (TSQ < 6), χ2(2, N = 10,110) = 2,504.6, P < 0.001.

Higher levels of PTSD and depressive symptoms were associated with younger age, F(2, 10107) = 66.8, P<0.001, and F(2, 10107) = 332.1, P < 0.001, respectively. Depressive symptoms differed significantly between genders, F(2, 10107) = 4.8, P = 0.008. Past psychiatric history was associated with more PTSD and depressive symptoms, t(2582) = 12.9, P < 0.001, and t(2590.4) = 15.2, P < 0.001, respectively. These demographic variables were controlled for in subsequent analyses.

Over half (n = 5,281; 52.2%) of the participants reported one or more direct TEs, 43.7% (n = 4,420) experienced only indirect TEs, and 4% (n = 409) reported no TEs. PTSD symptoms significantly differed between these groups, F(2,10107) = 573.03, P < 0.001, where symptoms were highest in those with direct exposure (mean = 4.74, SD = 3.56), followed by indirect exposure (mean = 2.62, SD = 3.26) and were lowest in those with no exposure (mean = 1.26, SD = 2.73).

In response to these precipitating events, a significant proportion of participants (n = 5,426; 53.7%) reported frequent event-based rumination involving at least one of these subtypes: anger (n = 3,396; 33.6%), injustice (n = 4,008; 39.6%), guilt (n = 3,079; 30.5%), and insecurity (n = 1,841; 18.2%). Compared to those with no or infrequent rumination, participants with frequent rumination showed significantly higher levels of PTSD symptoms, mean = 5.1, SD = 3.5 vs. mean = 2.1, SD = 2.9, t(10089.9) = 46.3, P < 0.001, and depressive symptoms, mean = 22.7, SD = 9.8 vs. mean = 15.6, SD = 9.5, t(9954.4) = 37.1, P < 0.001.

Table 2 presents the number of different classes of events reported. The number of precipitating events in each class (TEs, PEs, SLEs) was significantly correlated with PTSD and depressive symptoms, composite rumination levels, and each rumination subtypes (Pearson’s correlation coefficients ranging from r = 0.14 to 0.51 for PTSD and r = 0.14 to 0.43 for depressive symptoms, all P < 0.001). Significant variables were included in hierarchical regression analyses for PTSD and depressive symptoms.

Regression Models for PTSD and Depressive Symptoms

The first hierarchical regression model accounted for 32% of the variance in PTSD symptoms, F(8, 10045) = 592, P < 0.001. Past adversity was a significant predictor (β = 0.22, P < 0.001) and contributed to 2.6% of the variance after controlling for gender, age, and past psychiatric history. The 3 classes of events explained an additional 13.7% of variance in the third block. Rumination contributed to a further 12.5% of the variance. In the final model, rumination (β = 0.51), TEs (β = 0.48), and SLEs (β = 0.33) significantly predicted PTSD symptoms (all P < 0.001), while PEs did not (P = 0.35). Results were similar when the 2 items measuring indirect TEs exposure via media were removed, with the same set of predictors being significant (Supplementary Material S2). These predictors also remained significant after removing item 1 of the TSQ (to minimize content overlap) and after controlling for smartphone use (Supplementary Material S3 and S5).

The regression model for depressive symptoms explained 24.9% of the total variance, F(8, 10045) = 417.5, P < .001. Past adversity was also a significant predictor (β = 0.80, P < 0.001) and explained 2.2% of variance after controlled variables were entered. Precipitating events explained an additional 4.3% of the variance in the third block, and rumination added 9.8% of the variance. Rumination (β = 1.28, P < 0.001), SLEs (β = 1.08, P < 0.001), and PEs (β = 0.26, P = 0.016) predicted depressive symptoms. Notably, TEs were not a significant predictor (P = 0.53). These predictors remained significant after removing item 6 of the DASS-D (Supplementary Material S4).

Interaction between Prior and Recent Stress Exposure

In addition to the significant main linear effects of recent TEs, F(2, 10098) = 123.7, P < 0.001, and prior TEs, F(2, 10098) = 53.4, P < 0.001, a significant recent TEs × prior TEs interaction, F(4, 10098) = 3.7, P = 0.005, indicated the effect of recent TEs was amplified in those with more prior TEs. Figure 1A illustrates this potentiating effect. Both main effects and interaction effects remained after controlling for smartphone use (Supplementary Material S5). Post-hoc analysis of the interaction is provided in Supplementary Material S7.

Figure 1.

Interaction effects of prior and recent events for PTSD symptoms. (A) Prior TEs × recent TEs interaction. (B) Prior TEs × PEs interaction. (C) SLEs × recent TEs interaction. All main effects are significant, P < 0.001. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; PEs = COVID-19 pandemic-related events; SLEs = stressful life events; TEs = social unrest-related traumatic events.

Both PEs, F(2, 10098) = 23.8, P < 0.001, and prior TEs, F(2, 10098) = 156.8, P < 0.001, had significant linear main effects on PTSD symptoms, but with no significant interaction, F(2, 10098) = 0.2, P = 0.94. Figure 1B illustrates their cumulative effects on PTSD.

We then explored whether SLEs would prime responses to recent TEs. On top of the separate main effects of recent TEs, F(2, 10098) = 107.4, P < 0.001, and SLEs, F(2, 10098) = 65.2, P < 0.001, there was also a significant recent TEs × SLEs interaction effect, F(4, 10098) = 4.3, P = 0.002, for PTSD symptoms. Figure 1C shows the potentiating effects.

For depressive symptoms, each type of recent and prior events contributed significantly to increased symptom severity. These included recent TEs, F(2, 10098) = 23.8, P < 0.001, with prior TEs, F(2, 10098) = 10.8, P < 0.001; PEs, F(2, 10098) = 42.4, P < 0.001, with prior TEs, F(2, 10098) = 19.4, P < 0.001; and recent TEs, F(2, 10098) = 20.5, P < 0.001, with SLEs, F(2, 10098) = 50.5, P < 0.001. No interaction effect however was identified.

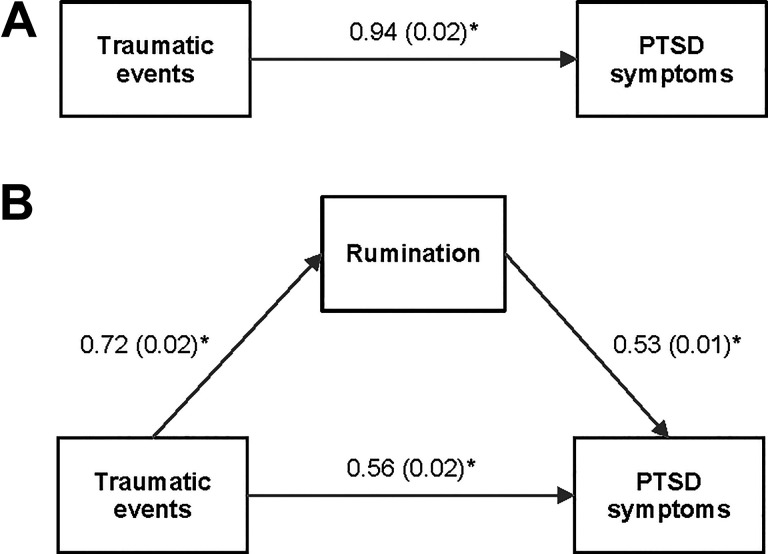

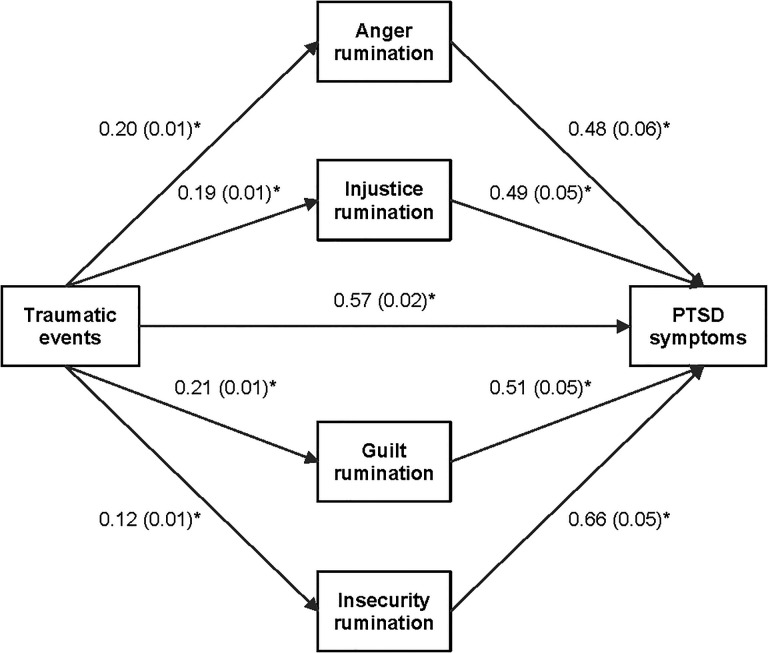

Event-based Rumination as a Mediator between TEs and PTSD Symptoms

Rumination significantly mediated the effect of TEs on PTSD symptoms (β = 0.38, standard error [SE] = 0.01, 95% CI = 0.35 to 0.41), accounting for 40.4% of the total effect (Figure 2). The subsequent multiple mediation model (Figure 3) showed that all 4 rumination subtypes were significant independent mediators of PTSD symptoms (anger: β = 0.09, SE = 0.01, 0.07 to 0.12; injustice: β = 0.09, SE = 0.01, 0.07 to 0.11; guilt: β = 0.11, SE = 0.01, 0.09 to 0.13; insecurity: β = 0.08, SE = 0.01, 0.07 to 0.09). Altogether they accounted for 39.9% of the total effect (β = 0.37, SE = 0.01, 0.35 to 0.40).

Figure 2.

Diagram illustrating (A) the relationship between social unrest-related traumatic events and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, and (B) after rumination is included as a mediator. Unstandardized regression coefficients are presented, with standard error in parentheses, *P < 0.001. PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder.

Figure 3.

Multiple mediation model for social unrest-related traumatic events and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, as mediated by 4 rumination subtypes (anger, injustice, guilt, and insecurity). Unstandardized regression coefficients are presented, with standard error in parentheses, *P < 0.001. PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder.

Discussion

Principal Findings: Interactions and Potentiation between Triggering Events

To the best of our knowledge, this study is one of the first to address how social unrest and the pandemic interacted to affect mental health. Emergent COVID-19 stressors were found to have added to prior TEs in contributing to PTSD symptoms. In parallel, recent TEs were potentiated by prior TEs to generate PTSD symptoms. Personal SLEs also interacted with TEs to potentiate PTSD. This suggests that TEs, PEs, and SLEs should be considered alongside one another in a multidimensional system consisting of evolving streams of events.

Although we found that TEs were more predictive of PTSD symptoms and COVID-19 events were more predictive of depressive symptoms, the different event classes generally additively contributed to both PTSD and depressive symptoms. In the interaction analyses between recent and prior events, TEs contributed not only to PTSD but also to depression, and likewise, SLEs contributed not only to depression but also to PTSD. This “crossover” of different classes of triggering events in their impact on PTSD and depression is in line with previous findings30,31 and suggests that there are shared common pathways bridging the 2 conditions.30

Mediating Role of Event-based Rumination in Event-induced PTSD Symptoms

The mediating role of event-based rumination supports previous suggestions that rumination may act as a risk factor for conditions including depression and PTSD.15,16 Rumination has been linked to a specific configuration of attentional processes,32 in which traumatic memory may be reinforced through a reconsolidation process.33 On each occasion that a traumatic memory is reactivated through rumination, new contextual information about the emotional and cognitive contents of the current mental states may be amalgamated into the memory trace, resulting in potentiation effects between events in successive time periods.

Rumination in our study required not only frequent repetitive thoughts but also disruptions to other tasks, suggesting a significant impact on cognition and functioning. The tentative subtypes of rumination we observed extended beyond the conventional self-focused “depressive rumination” to include repetitive thoughts in reaction to external events (i.e., anger, injustice, guilt, and insecurity). An important observation was the role of injustice rumination, which has been identified in a previous longitudinal study to be one of the most impactful determinants of long-term outcomes.18 In contrast to depressive rumination, event-based rumination have generally been less well-studied. Given their potentially important mediating roles, more attention to this construct in future research is warranted.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study concurs with previous findings that poorer outcomes were associated with past adversity, past psychiatric history, and female gender.34

Our study objective was to examine the relationship between stress exposure and psychopathology. While studies with nonrandom samples have demonstrated robustness in examining associations between variables,35 we acknowledge that this study does not allow for estimations of mental condition prevalence or the definitive ascertainment of causal directions between variables, which would require epidemiological and longitudinal studies, respectively. There may also be discrepancies between the rates of self-rated dimensional symptoms and those based on clinical diagnostic assessments. We recommend caution in generalizing the study findings to the entire population.

We considered that measures of event-based rumination need to be customized according to the actual population circumstances. Although our measures of event-based rumination showed relatively good reliability and validity, further research into rumination, as well as the subdomains we explored in this study, may help to consolidate our findings. While we focused on rumination in response to population-level external events, it is possible that internal self-focused rumination also played a role in the symptoms observed. The role of both internally and externally oriented rumination and their potential interactions should be further addressed in future studies.

Lastly, apart from direct trauma exposure, we also observed that indirect media exposure could contribute to PTSD symptoms. This effect remained significant after controlling for smartphone use. More direct measures of the frequency of TEs viewing online in future studies may help to clarify the effects of media exposure.

Research and Clinical Implications

We provided preliminary observations suggesting that event-based rumination may that might underlie play an important mediating role. Memory reconsolidation was proposed to be a process that underlie the linkage between event-based rumination and symptoms. These potential insights, if supported in future studies, may help to anticipate the impact of external events on mental health.

The co-occurrences of protests and pandemics are likely not incidental. Both are prolonged, widespread, and may recur after apparent quiescence. The far-reaching waves of protests and the global experiences of COVID-19 suggest our findings are relevant to not just Hong Kong, but also to other contemporary societies, such as the United States, United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Canada.5,6

The current survey afforded an opportunity to observe how social unrest and a global health crisis interacted in a dynamic manner to contribute to symptoms of PTSD and depression.

Early interventions to reduce rumination may potentially be important in limiting the mental health consequences on the population. Future work should be done within an integrative framework that can accommodate past, recurrent, and ongoing exposures to multiple streams of events.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, sj-docx-1-cpa-10.1177_0706743720979920 for Mental Health Risks after Repeated Exposure to Multiple Stressful Events during Ongoing Social Unrest and Pandemic in Hong Kong: The Role of Rumination: Risques pour la santé mentale après une exposition répétée à de multiples événements stressants d’agitation sociale durable et de pandémie à Hong Kong: le rôle de la rumination by Stephanie M. Y. Wong, Christy L. M. Hui, Corine S. M. Wong, Y. N. Suen, Sherry K. W. Chan, Edwin H. M. Lee, W. C. Chang and Eric Y. H. Chen in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: SWMY and EYHC designed the study, analyzed the data and interpreted results, searched the published work, and wrote the paper. All authors revised the manuscript and approved the final version. Data are not publicly available due to confidentiality reasons in accordance with ethics approval given by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster. Data inquiries may be submitted to the corresponding author.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: EYHC has received speaker honoraria from Otsuka and DSK BioPharma, research funding from Otsuka, participated in paid advisory boards for Janssen and DSK BioPharma, and received funding to attend conferences from Otsuka and DSK BioPharma, all outside of the submitted work. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: YN. Suen, PhD  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2766-8476

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2766-8476

Eric YH. Chen, MD, FRCPsych  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5247-3593

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5247-3593

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Lindsay B. No COVID-19 cases connected to huge Vancouver protests against anti-Black racism. CBC News; 2020. [accessed 2020 Sept 14]. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/no-covid-19-cases-connected-to-huge-vancouver-protests-against-anti-black-racism-1.5639883/ Last updated 2020 Jul 7

- 2. McVeigh K. Protests predicted to surge globally as Covid-19 drives unrest. The Guardian; 2020. [accessed 2020 Sept 14]. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/jul/17/protests-predicted-to-surge-globally-as-covid-19-drives-unrest/ Last updated 2020 Oct 15

- 3. Ni MY, Kim Y, McDowell I, et al. Mental health during and after protests, riots and revolutions: a systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2020;54(3):232–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Neria Y, Nandi A, Galea S. Post-traumatic stress disorder following disasters: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2008;38(4):467–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ni MY, Yao XI, Leung KS, et al. Depression and post-traumatic stress during major social unrest in Hong Kong: a 10-year prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10220):273–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rogers JP, Chesney E, Oliver D, et al. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(7):611–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fragkaki I, Thomaes K, Sijbrandij M. Posttraumatic stress disorder under ongoing threat: a review of neurobiological and neuroendocrine findings. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2016;7(1):30915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gray MJ, Litz BT, Hsu JL, Lombardo TW. Psychometric properties of the life events checklist. Assessment. 2004;11(4):330–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:293–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shek DT. Protests in Hong Kong (2019–2020): a perspective based on quality of life and well-being. Appl Res Qual Life. 2020:15:619–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Arranz A. Arrested Hong Kong protesters: how the numbers look one year on. South China Morning Post; 2020. [accessed 2020 Jun 14]. https://multimedia.scmp.com/infographics/news/hong-kong/article/3088009/one-year-protest/

- 12. Radio Television Hong Kong. Carrie Lam remark will add to face mask panic: DAB. Radio Television Hong Kong. Radio Television Hong Kong; 2020. [accessed 2020 Sept 10]. https://news.rthk.hk/rthk/en/component/k2/1506571-20200204.htm/ Published date 2020 Feb 4.

- 13. Lau JT, Yang X, Pang E, Tsui H, Wong E, Wing YK. SARS-related perceptions in Hong Kong. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11(3):417–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wan K-M, Ho LK-k, Wong NW, Chiu A. Fighting COVID-19 in Hong Kong: the effects of community and social mobilization. World Dev. 2020;134:105055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2008;3(5):400–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ehlers A, Clark DM. A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2000;38(4):319–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Watkins ER. Depressive rumination and co-morbidity: evidence for brooding as a transdiagnostic process. J Ration Emot Cogn Behav Ther. 2009;27(3):160–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Silove D, Liddell B, Rees S, et al. Effects of recurrent violence on post-traumatic stress disorder and severe distress in conflict-affected Timor-Leste: a 6-year longitudinal study. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(5):e293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Masten AS, Narayan AJ. Child development in the context of disaster, war, and terrorism: pathways of risk and resilience. Annu Rev Psychol. 2012;63:227–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brewin CR, Rose S, Andrews B, et al. Brief screening instrument for post-traumatic stress disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181(2):158–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wu KK, Leung PW, Wong CS, et al. The Hong Kong Survey on the epidemiology of trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2019;32(5):664–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the Beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33(3):335–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lu S, Hu S, Guan Y, et al. Measurement invariance of the depression anxiety stress scales-21 across gender in a sample of Chinese university students. Front Psychol. 2018;9:2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Holman EA, Garfin DR, Silver RC. Media’s role in broadcasting acute stress following the Boston marathon bombings. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(1):93–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lawshe CH. A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers Psychol. 1975;28(4):563–575. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Polit DF, Beck CT. The content validity index: are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29(5):489–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lacasse Y, Godbout C, Series F. Health-related quality of life in obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur Respir J. 2002;19(3):499–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: a Regression-based Approach. NewYork (NY): Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Flory JD, Yehuda R. Comorbidity between post-traumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder: alternative explanations and treatment considerations. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2015;17(2):141–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schock K, Böttche M, Rosner R, Wenk-Ansohn M, Knaevelsrud C. Impact of new traumatic or stressful life events on pre-existing PTSD in traumatized refugees: Results of a longitudinal study. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2016;7(1):32106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Whitmer AJ, Gotlib IH. An attentional scope model of rumination. Psychol Bull. 2013;139(5):1036–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hupbach A, Gomez R, Hardt O, Nadel L. Reconsolidation of episodic memories: a subtle reminder triggers integration of new information. Learn Mem. 2007;14(1-2):47–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sareen J. Posttraumatic stress disorder in adults: impact, comorbidity, risk factors, and treatment. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(9):460–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Heiervang E, Goodman R. Advantages and limitations of web-based surveys: evidence from a child mental health survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011;46(1):69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, sj-docx-1-cpa-10.1177_0706743720979920 for Mental Health Risks after Repeated Exposure to Multiple Stressful Events during Ongoing Social Unrest and Pandemic in Hong Kong: The Role of Rumination: Risques pour la santé mentale après une exposition répétée à de multiples événements stressants d’agitation sociale durable et de pandémie à Hong Kong: le rôle de la rumination by Stephanie M. Y. Wong, Christy L. M. Hui, Corine S. M. Wong, Y. N. Suen, Sherry K. W. Chan, Edwin H. M. Lee, W. C. Chang and Eric Y. H. Chen in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry