Abstract

Background and aim of the work:

Palliative Care professionals are exposed to intense emotional environment. This puts them at risk for Compassion Fatigue and Burnout. The protective factors that can counter their onset are Compassion Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment and Resilience. Expressive Writing is a valid tool for adapting to traumatic events and enhancing psychological well-being. Aim of this study is to evaluate the effect of the Expressive Writing in Palliative Care professionals on Compassion Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment, Resilience, Compassion Fatigue and perceived distress.

Methods:

Prospective experimental study with experimental/control groups and pre/post measurements. 50 Palliative Care professionals were recruited in Northern and Central Italy. Participants filled: Organizational Commitment Questionnaire; ProQol - revision III; Resilience Scale for Adults; Impact of Event-Scale Revised; Emotion Thermometer; ad hoc questionnaire for the evaluation of protocol usefulness.

Results:

Wilcoxon test demonstrated change in Continuative Commitment (Z = -3.357, p = .001), anger (Z = -2.214, p = .027), sleep (Z = -2.268, p = .023), help (Z = -2.184, p = .029), intrusiveness (Z = -2.469, p = .014), hyperarousal (Z = -2.717, p = .007), and total IES (Z = -2.456 , p =, 014). Mann Whitney test showed a significantly lower score on post-test Intrusiveness in the experimental group (U = 202, p = .038).

Conclusions:

The Expressive Writing intervention was effective in improving organizational and emotional variables. Expressive Writing supports healthcare professionals in relieving the burden of traumatic episodes, ordering associated thoughts and emotions, and implementing a process of deep comprehension.

Keywords: Palliative Care, Expressive Writing, Resilience, Stress, Compassion Satisfaction, Organizational commitment

Introduction

Health professions are defined professions that deal with assisting and providing care to people who suffer from both physical and emotional suffering (1). Healthcare professionals working in Palliative Care are exposed to emotionally intense situations daily, both from the point of view of the workload and the emotional burden that caring for dying patients requires, facing conditions such as compassion fatigue and burnout. Compassion fatigue (CF) refers to a psychological disorder commonly caused by the attendance of others’ pain (2). Studies have shown that CF and burnout (BO) negatively affect the psycho-physical well-being and performance of healthcare professionals in Palliative Care: past clinical experiences, physical exhaustion, the experience of a traumatic event, discomfort towards colleagues, emotional exhaustion, and social isolation are all determining factors in the appearance of CF and BO (3). The protective factors that can counteract the onset of CF and BO are Compassion Satisfaction (CS), Organizational Commitment (OC) and Resilience (Re). CS encompasses the positive effects that an individual can derive from working with suffering people, including positive feelings about helping others, contributing to the good of society and more generally the pleasure of “doing the job well”; in fact, it turns out to be a protective factor for professionals who work in contact with death, but only if they have the right awareness and skills in dealing with these situations (4).

The OC promotes a positive feeling that indicates the quality of the bond that the individual establishes with his or her organization; this factor is able to moderate stress and its symptoms enhancing coping strategies. The OC is effective in decreasing the negative effects of Burnout and Compassion Fatigue while increasing the Compassion Satisfaction in the professional (5).

Resilience is understood as the ability of individuals to cope with stress and adversity and come out strengthened or even transformed; it is a necessary skill for nurses to deal with situations of moral distress, BO and CF and during daily clinical activity (6). In the palliative care setting, it indicates the ability of an individual to adapt to complex situations both from a professional and an emotional point of view and to find the ability to overcome deep suffering (7).

It has been shown that in healthcare professionals the increase in CF and BO (negative factors) corresponds to a decrease in CS (protective factor); these factors depend on the area in which the professional works and the characteristics of the job. Palliative care is, in fact, significantly involved in the negative relationship between CS and BO and CS and CF (5). Secondly, the tendency to develop coping strategies positively influences CS and negatively BO; from this it can be deduced that the professional who tends to be more inclined to the development of effective coping strategies (especially through spiritual reflection on death and mourning), also matures preventive defence mechanisms from Burnout (8).

The scientific literature suggests Expressive Writing (EW) as a valid tool for people’s adjustment to traumatic events, for the prevention of stress-related health problems, acting on the psycho-physical well-being of those who use it. The EW is an intervention designed to rework stressful situations and difficult emotional contexts through the personal production of a text written in one or more sessions.

The studies conducted so far using Expressive Writing have shown satisfactory results as a positive effect on mood (9) and on the immune system (10). Furthermore, the EW protocols have proved effective on mild forms of depression (11), on anxiety (12), on eating disorders (13), on different types of post-traumatic stress (14), and on stress and job satisfaction (15). In the healthcare context, the efficacy of Expressive Writing has been demonstrated in cancer patients for the reduction of emotional distress (16) and in those affected by HIV (17).

An Italian study conducted on health professionals has shown that EW represents an important strategy for preventing and managing the effects of Compassion Fatigue (CF) and decreasing the incidence of Burnout (BO) by improving the use of individual coping strategies (18).

Confirmed the effectiveness of Expressive Writing in contexts with a high level of emotional distress and in increasing the level of resilience (19; 20), we want to investigate whether its use by Palliative Care professionals can lead to an increase in protective factors such as CS, OC and Re and a decrease in negative factors such as CF, thus bringing positive repercussions both for the operator himself and for the organization of the work structure, the management of costs and resources.

Aims

Objective of the study: to evaluate the effect of the Expressive Writing protocol in Palliative Care professionals on the levels of Compassion Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment, Resilience, Compassion Fatigue and perceived distress.

Secondary objective of the study: to evaluate the perception of the usefulness of the Expressive Writing protocol by the participants.

Methods

This was a prospective experimental study with two groups (Expressive Writing experimental group / Neutral Writing control group) and two measurements: pre / post with a time span of 3 weeks (21).

Sample

50 participants were recruited through a balanced convenience sampling by setting. As Palliative care professionals were included: nurses, social and health workers, auxiliaries, doctors, psychologists, within hospitals and services in northern and central Italy.

Participants met the following criteria:

- speak and write fluently in Italian,

- have expressed an explicit desire to participate in the study, after signing the informed consent,

- have been working in Palliative Care at least 24 hours a week without interruption for at least 6 months (22).

The duration of the study was 7 months, from August 2019 to February 2020.

Instruments

A battery of questionnaires was used to evaluate the effects of EW’s intervention, composed as follows:

Socio-demographic section collecting gender, age, and professional role;

The Italian version (23) of the Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (24) consisting of 25 items with a 6-point Likert scale response (from 1 = completely disagree to 6 = completely agree) which converge into 3 independent factors corresponding to the three components of the Organizational Commitment: - the affective commitment (10 items), - the continuance commitment (7 items) and the normative commitment (8 items);

The Italian version of the Compassion Satisfaction and Compassion Fatigue rating scale taken from the Professional Quality of Life Scale (4). The scale consists of 30 items with a 5-point Likert scale response from 1 (never) to 5 (very often); each participant must consider the statements relating to himself / herself and his current situation and select the answer that has been most true in the last thirty days;

The Italian version (25) of the Resilience Scale for Adults (RSA, 26) consisting of 33 items with a 7-point Likert scale response (from 1 = not at all to 7 = totally agree), which evaluate protective resources on six determining factors: social competence, structured style, self-perception, planning for the future, family cohesion and social resources;

The Italian version (27) of the impact of event-scale revised (IES-R) (28). It is a standardized psychometric scale, consisting of 30 items and three sub-dimensions (re-experience, hyperarousal, avoidance). Each item is evaluated on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely) with respect to a traumatic experience lived in the last 7 days;

The Italian version of the Emotion thermometer (29) evaluating emotions such as: anxiety, depression, sleep, stress, depressed mood and help. These thermometers are based on a scale from 0 (no emotion) to 10 (maximum emotion);

- Ad hoc questionnaire evaluating the usefulness of the writing sessions consisting of four questions:

- How useful do you think the writing experience was?

- Did you feel relief after using it?

- Did you feel uncomfortable writing?

- Would you recommend someone to write?

For each question, the participant was asked to evaluate the extent of usefulness on the scale: not at all, a little, enough, a lot. This tool was used in the post-test phase only with the participants who joined the EW group.

Procedure

The study developed in 3 sessions.

Session 1: the participants of both groups first completed the socio-demographic questionnaire and the three scales for the evaluation of outcome parameters. Subsequently, each participant was given the writing mandate lasting 20 minutes based on the group to which he/she was assigned (EW vs NW).

Session 2: Over a 3-week time span, participants were invited to perform 3 additional EW or NW sessions, 3-4 days apart, individually at home (30).

Session 3: After completing the writing sessions, a meeting was held with the researchers, during which the same scales as in session 1 were administered. The experimental group was also administered the ad hoc questionnaire.

Expressive Writing Protocol

In the EW mandate, participants were required to write for 20 consecutive minutes about a traumatic, stressful and emotionally significant event, the same for all writing sessions, concerning their professional life. NW’s mandate used as a comparison tool required participants to describe an event that occurred as objectively as possible without dwelling on emotions, thoughts and sensations experienced.

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (https://www.wma.net/e/policy/b3.htm). The study began once the positive opinion of the Ethics Committee and the clearance / authorization of the Company Management had been obtained.

The study participants were adequately informed by the investigator on the purposes and objectives of the study and signed specific informed consent to the study and the processing of personal data, which was filed together with the study documentation.

Results

In all, 50 participants were recruited, divided into two groups: Expressive Writing (EW; N = 22, 44%) and Neutral Writing (Neutral Writing, NW; N = 28, 56%).

Female participants made up 78.0% while male 22.0%.

The age of the sample ranges from 26 to 70, with an average of 44.74 and a standard deviation of 9.876. All participants all have more than six months of experience in the field of Palliative Care (as per the inclusion criterion); 64% are nurses, 18% doctors, 12% OSS, 2% auxiliaries, 2% psychologists and 2% nursing coordinators.

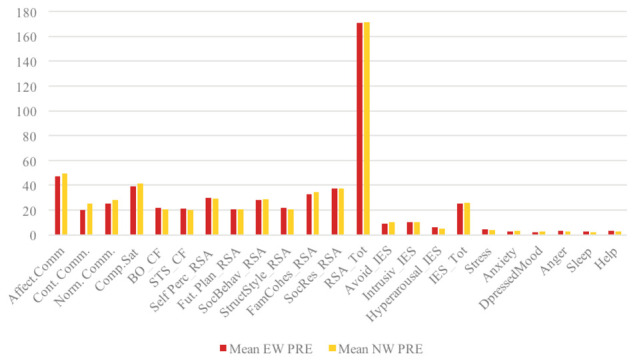

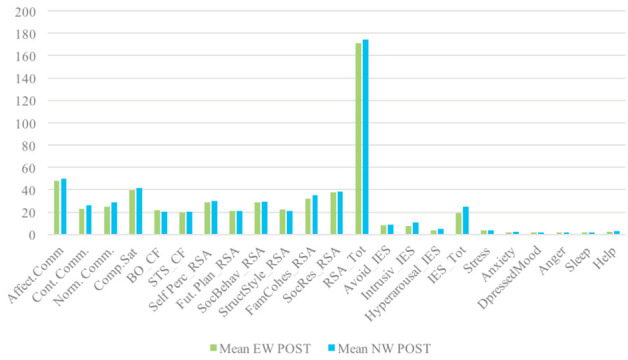

For both groups, mean, standard deviation and distribution indices (asymmetry and kurtosis) were calculated at baseline (Fig. 1) and post-treatment (Fig. 2) for each variable examined.

Figure 1.

EW and NW means comparison before the intervention

Figure 2.

EW and NW means comparison after the intervention

The data were not normally distributed, therefore, also taking into consideration the number of EW and NW participants, non-parametric statistics were used.

In particular, the Wilcoxon test for paired samples was used to evaluate the presence of significant PRE-POST differences within the sample and the Mann Whitney test for independent samples for the presence of significant differences between the samples.

The Wilcoxon test demonstrated a statistically significant change in the Continuative Commitment scale (Z = -3.357, p = .001). The pre-test average CC value is 19.82 and the post-test value is 23.05.

No significant differences were identified on Resilience and on Compassion Satisfaction and Compassion Fatigue.

Wilcoxon’s test also demonstrated a change on the scale of the Emotion Thermometer, in particular regarding the following dimensions: anger (Z = -2.214, p = .027); sleep (Z = -2.268, p = .023); help (Z = -2.184, p = .029). The mean pre-test anger value is 3.09 and post-test is 1.73. The pre-test mean sleep value is 2.45 and post-test is 1.41. The pre-test mean help value is 3.50 and the post-test value is 2.55.

It was also shown a change on the Impact of Event Scale with respect to the dimensions of intrusiveness (Z = -2.469, p = .014), hyperarousal (Z = -2.717, p = .007), and total IES (Z = - 2.456, p = .014).

Mann Whitney’s U-test showed that the group that received the Expressive Writing intervention scored significantly lower Intrusiveness on the Post-test than the control group (U = 202, p = .038); this difference had no statistical significance in the baseline assessment.

Finally, the evaluation questionnaire of the usefulness of the Expressive Writing intervention quantifies the satisfaction of the intervention in a range of scores from 4 to 16. The results reported an average value of 11.77 with a standard deviation of 2.137.

Discussions

The primary objective of this study was the evaluation of the effects of an Expressive Writing protocol in palliative care professionals, regarding the outcomes of Compassion Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment, Resilience, Compassion Fatigue and Perceived Stress. The secondary objective was the evaluation of the perception of its utility by the professionals. The expected results of the study were an improvement in Compassion Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment and Resilience, and a decrease in Compassion Fatigue and in perceived stress indices (stress, anxiety, depressed mood, anger, sleep disturbances, request for help, avoidance, intrusiveness, and hyperarousal) in the experimental group.

In this study, the Organizational Commitment was evaluated in its three components, identified and described by John Meyer and Nancy Allen in 1997 (31): Affective, Continuance and Normative Commitment.

From the results that emerged in this research, the Continuance Commitment significantly increased in the EW group after the Expressive Writing intervention (Z = -3.357, p = .001). This supports and confirms that writing about a past trauma helps to rework it, reducing physiological stress on the body, being expressive writing a form of written therapy (33; 34; 35) and that in healthcare organizations increased work engagement and responsibility are key factors in ensuring an efficient and active workforce in the healthcare sector (31; 36; 32). It can then be hypothesized that the increase in Continuance commitment may be attributable to the fact that the professionals felt more inclined to commitment and inclined to continue the professional relationship after the use of the EW.

No significant differences emerged in the questionnaires related to Resilience and Compassion Fatigue, after the intervention. Previous research in the literature shows that resilience is a necessary skill for nurses to deal with situations of moral distress, Burnout and CF during daily clinical activity (7; 6; 37). Therefore, the fact that no significant difference in resilience emerged could be mainly attributable to the non-variation of the Compassion Fatigue parameter.

As regards the Compassion Satisfaction variable, it is interesting to underline how, although under the statistical significance, in the experimental group the CS increased compared to the control group which maintained a stable value in the PRE and POST intervention. The slight increase in Compassion Satisfaction, i.e. the satisfaction derived from one’s ability to work efficiently, to contribute to the good of the work environment and society (4), suggests that the health professionals involved are already able to maintain good levels of CS through self-care strategies developed over time such as regular exercise, adequate hours of sleep, healthy nutrition, compensation in personal life, opportunities for relaxation, stress reduction, meditation practices, spirituality, communication skills, psychological support in the workplace, ability to ask for help, ability to set limits on time and use of one’s mental, physical and psychological resources (38; 39; 8).

The EW intervention may have been helpful in reactivating these skills in professionals already acquired them transversally in their lives.

A significant reduction after EW intervention is evident in the parameters contained in the Emotions Thermometer: sleep disorders, anger, and request for help. EW is a real therapy because it uses means and methods to cure and is applicable to both those who care and those who are treated (40). If a trauma is not treated properly, it can lead to physiological changes in the organism (33) while writing and narrating traumatic episodes of one’s life is a way to relive them, to analyse them and to order thoughts and states of mind connected to it, thus implementing a process of comprehension of the event (41). Furthermore, not being able to share an emotionally intense trauma with one’s social network is more harmful than not having a solid social network at all (42).

According to Bernard, shift work, especially if very long, and the poorly defined sleep-wake rhythm due to night shifts are typical characteristics of health workers that can compromise the duration and quality of sleep, which, instead, can benefit from the ability to cope with the pressures generated by moral and work obligations (6).

Following the EW intervention, statistically significant reductions were observed in the area of intrusiveness and total IES-R (Impact of Event Scale - Revised), a score consisting of the sum of the averages of the avoidance, intrusiveness and hyperarousal parameters. In the Expressive Writing mandate, it was required to describe several times an event considered traumatic by the healthcare professional and to dwell on emotions and moods, with the aim of reducing the intrusiveness of the trauma through a free expression of what happened. In the Neutral Writing mandate, a description of the event was requested as objective, excluding thoughts and emotions. Precisely by virtue of these characteristics, Neutral Writing had no effect on intrusiveness, while a significant decline was found in the cohort of professionals subjected to Expressive Writing. Therefore, apparently, this writing protocol would seem to have a positive impact on the person who uses it, as previously confirmed by the studies of Pennebacker (9) and Seagal (43).

Conclusions

The objective of this research was to investigate the usefulness of an EW protocol to increase the levels of Compassion Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment, Resilience (protective factors) and reduce perceived Stress in Palliative Care professionals with respect to Compassion Fatigue and Burnout (negative factors). All this supported by the previous review of the literature. This study highlighted how the Expressive Writing intervention was effective in improving some organizational and emotional variables in professionals operating in Palliative Care.

The limits identified in this protocol lie in the fact that the predetermined number of 66 participants was not met, but only 50, due to the large number of questionnaires proposed before and after the writing intervention for both the experimental group and the control group (the initial expectation of the participants was to fill in a simple and immediate questionnaire). This did not allow to carry out more complete and decisive analysis of the sample taken into consideration, but significant results were nevertheless achieved. Therefore, in the future, to facilitate participation in this study, the number of questionnaires could be reduced, selecting the most relevant to the research objectives.

Although Expressive Writing is useful in helping the professionals to overcome difficult moments in the care provided to the dying patient, participants often found it difficult to describe an event that put a strain on them, leading them to give up participating in the project. It should be borne in mind that writing is not a skill of all health professionals and it might be interesting to investigate what other methods could be useful for professionals to re-elaborate the emotionally charged work experience.

Conflicts of interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

References

- 1.Klein MD, Beck AF, Henize AW, Parrish DS, Fink EE, Kahn RS. Doctors and lawyers collaborating to HeLP children: outcomes from a successful partnership between professions. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(3):1063–1073. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Figley CR. Compassion fatigue as secondary traumatic stress disorder: An overview”. In: Figley C.R, editor. Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. Vol. 23. Brunner Routledge, New York; 1995. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kase S, Waldman E, Weintraub A. A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study of Compassion Fatigue (CF), Burnout (BO), and Compassion Satisfaction (CS) in Pediatric Palliative Care (PPC) Providers (S704) J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(2):657–658. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stamm BH. Professional quality of life: Compassion satisfaction and fatigue subscales, Version V (ProQOL) Center for Victims of Torture. 2009 Retrieved from https://proqol.org/ProQol_Test.html. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slocum-Gori S, Hemsworth D, WY, Chan W, Carson A, Kazanjian A. “Understanding Compassion Satisfaction, Compassion Fatigue And Burnout: A survey of the hospice palliative care workforce. Palliat Med. 2011;27(2):172–178. doi: 10.1177/0269216311431311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernard N. Resilience and professional joy: a toolkit for nurse leaders. Nurse Lead. 2019;17(1):43–48. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Back AL, Steinhauser KE, Kamal AH, Jackson VA. Building Resilience for Palliative Care Clinicians: An Approach to Burnout Prevention Based on Individual Skills and Workplace Factors. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;52(2):284–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanso N, Galiana L, Oliver A, Pascual A, Sinclair S, Benito E. Palliative Care Professionals’ Inner Life: Exploring the Relationships Among Awareness, Self-Care, and Compassion Satisfaction and Fatigue, Burnout, and Coping With Death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50:200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pennebaker JW, Beall SK. Confronting a traumatic event: Toward an understanding of inhibition and disease. J Abnorm Psychol. 1986;95(3):274–281. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.95.3.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pennebaker JW, Kiecolt-Glaser J, Glaser R. Disclosure of traumas and immune function: health implications for psychotherapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(2):239–245. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frattaroli J. Experimental disclosure and its moderators: a meta-analysis”. Psychol Bull. 2006;132(6):823–865. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Emmerik AAP, Kamphuis JH, Emmelkamp PMG. Treating acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder with cognitive behavioral therapy or structured writing therapy: a randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77(2):93–100. doi: 10.1159/000112886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.East P, Startup H, Roberts C, Schmidt U. Expressive Writing and Eating Disorder Features: a preliminary trial in a student sample of the impact of three writing tasks on eating disorder symptoms and associated cognitive, affective and interpersonal factors. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2010;18(3):180–196. doi: 10.1002/erv.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoyt T, Yeater E. The effects of negative emotion and expressive writing on post traumatic stress symptoms. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2011;30(6):549–569. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sadovnik A, Sumner K, Bragger J, Pastor SC. Effects of expressive writing about workplace on satisfaction, stress and well-being”. Journal of Academy of Business and Economics. 2011;11(4):231–237. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gallo I, Garrino L, Di Monte V. L’uso della scrittura espressiva nei percorsi di cura dei pazienti oncologici per la riduzione del distress emozionale: analisi della letteratura. [Using Expressive Writing in the care pathways for oncological patients to reduce emotional distress: literature analysis] Prof Inferm. 2015;68(1):29–36. doi: 10.7429/pi.2015.681029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Metaweh M, Ironson G, Barroso J. The Daily Lives of People with HIV Infection: A Qualitative Study of the Control Group in an Expressive Writing Intervention. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2016;27(5):608–622. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tonarelli A, Cosentino C, Artioli D, Borciani S, Camurri E, Colombo B, D’Errico A, Lelli L, Lodini L, Artioli G. Expressive writing. A tool to help workers. Research project on the benefits of expressive writing. Acta Biomed. 2017;88(5):13–21. doi: 10.23750/abm.v88i5-S.6877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenbaum C.A, Javdani S. Expressive writing intervention promotes resilience among juvenile justice-involved youth. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2017;73:220–229. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glass O, Dreusicke M, Evans J, Bechard E, Wolever RQ. Expressive writing to improve resilience to trauma: A clinical feasibility trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2019;34:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mosher CE, DuHamel KN, Lam J, Dickler M, Li Y, Massie MJ, Norton L. Randomized trial of expressive writing for distressed metastatic breast cancer patients. Official Journal of the European Health Psychology Society. 2012;27:88–100. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2010.551212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaur A, Sharma MP, Chaturvedi SK. Professional Quality of Life among Professional Care Providers at Cancer Palliative Care Centers in Bengaluru, India”. Indian J Palliat Care. 2018;24(2):167–172. doi: 10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_31_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pierro A, Lombardo I, Fabbri S, Di Spirito A. Evidenza Empirica della Validità Discriminante delle Misure di Job Involvement e Organizational Commitment: Modelli di Analisi Fattoriale e Confermativa (via LISREL). [empirical evidence of the discriminant validity of Job Involvement and Organizational Commitment: Factorial and confirmative analysis models (via LISREL)] TPM Test Psychom Methodol Appl Psychol. 1995;2:1. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allen NJ, Meyer JP. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. J Occup Health Psychol. 1990;63:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Capanna C, Stratta P, Hjemdal O, Collazzoni A, Rossi A. The Italian validation study of the resilience scale for adults (RSA) BPA-Applied Psychology Bulletin. 2015;63(272) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friborg O, Hjemdal O, Rosenving JH, Martinussen M. A new rating scale for adult resilience: what are the central protective resources behind healthy adjustment? Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2003;12(2):65–76. doi: 10.1002/mpr.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pollice R, Bianchini V, Roncone R, Casacchia M. Distress psicologico e disturbo post-traumatico da stress (DPTS) in una popolazione di giovani sopravvissuti al terremoto dell’Aquila [Psychological distress and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in a population of young survivors to L’Aquila earthquake] Riv Psichiatr. 2012;47(1):59–64. doi: 10.1708/1034.11292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weiss DS. The Impact of Event Scale: Revised. Cross-Cultural Assessment of Psychological Trauma and PTSD. In: Wilson J.P, Tang C.S, editors. International and Cultural Psychology Series. Boston, MA: Springer; 2007. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-70990-1_10 . [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitchell AJ. Pooled results from 38 analyses of the accuracy of distress thermometer and other ultra-short methods of detecting cancer-related mood disorder. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(29):4670–4681. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Middendorp H, Sorbi MJ, Van Doornen LJP, Bijlsma JWJ, Geenen R. Feasibility and induced cognitive-emotional change of an emotional disclosure intervention adapted for home application”. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66(2):177–87. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Starnes BJ, Truhon SA. A primer on Organizational Commitment. Journal of Quality Technology. 2009;6:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khaleh LABC, Naji S. The relationship between organizational commitment components and organizational citizenship behavior in nursing staff”. International Journal of medical Research & Health Science. 2016;5:173–179. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pennebaker JW, Chung CK. “Expressive writing: connection to physical and mental health”. The Oxford handbook of health psychology. 2011:417. Cap.18. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lo Iacono G. Lo studio sperimentale della scrittura autobiografica: la prospettiva di James Pennebaker [The experimental study of autobiographical writing: James Pennebaker’s perspective] Rivista di Psicologia dell’Emergenza e dell’Assistenza Umanitaria [Journal of Emergency Psychology and Humanitarian Care] 2016;16:34–60. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tonarelli A, Cosentino C, Tomasoni C, Nelli L, Damiani I, Goisis S, Sarli L, Artioli G. Expressive writing. A tool to help health workers of palliative care. Acta Biomed. 2018;89(6):35–42. doi: 10.23750/abm.v89i6-S.7452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nehmeh R. What is Organizational commitment, why should managers want it in their workforce and is there any cost effective way to secure it?”. SMC working paper. 2009. Retrieved from: http://www.swissmc.at/Media/Ranya_Nehmeh_working_paper_05-2009.pdf .

- 37.Lin C, Liang H, Han C, Hsieh C. Professional resilience among nursing working in an overcrowded emergency department in Taiwan”. Int Emerg Nurs. 2019;42:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2018.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lombardo B, Eyre C. Compassion fatigue: a nurses’ primer. Online J Issues Nurs. 2011;16(1) doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol16No01Man03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanchez-Reilly S, Morrison LJ, Carey E, Bernacki R, O’Neill L, Kapo J, Periyakoil VS, deLima Thomas J. Caring for oneself to care for others: physicians and their selfcare. J Support Oncol. 2013;11(2):75–81. doi: 10.12788/j.suponc.0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wright J. Online counselling: Learning from writing therapy”. Br J Guid Counc. 2002;30(3):285–298. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smorti A. Narrazioni: cultura, memorie e formazione del sé [Narratives: culture, memories and self creation] Giunti. 2007 Firenze. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cole M. Cultural psychology: A once and future discipline. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seagal JD, Pennebaker JW. University of Texas, Austin; 1997. Expressive writing and social stigma: benefit from writing about being a group member”. Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]