Abstract

Objective

Impairments in executive functions and learning are common in HIV disease and increase the risk of nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy. The mixed encoding/retrieval profile of HIV-associated deficits in learning and memory is largely driven by dysregulation of prefrontal systems and related executive dysfunction. This study tested the hypothesis that learning may be one pathway by which executive dysfunction disrupts medication management in people living with HIV (PLWH).

Method

A total of 195 PLWH completed a performance-based laboratory task of medication management capacity and clinical measures of executive functions, verbal learning and memory, and motor skills.

Results

Executive functions were significantly associated with verbal learning and medication management performance. In a model controlling for education, learning significantly mediated the relationship between executive functions and medication management, and this mediation was associated with a small effect size. In particular, executive dysfunction was associated with diminished use of higher-order learning strategies. Alternate models showed that executive functions did not mediate the relationship between learning and medication management nor did motor skills mediate the relationship between executive functions and medication management.

Conclusions

PLWH with executive dysfunction may demonstrate difficulty in learning new information, potentially due to ineffective strategy use, which may in turn put them at a higher risk for problems managing their medications in the laboratory. Future studies may wish to investigate whether compensatory neurocognitive training (e.g., using more effective learning strategies) may improve medication management among PLWH.

Keywords: medication adherence, memory, neuropsychological assessment, AIDS, functional status

Introduction

Since the introduction of combination antiretroviral therapies (cART), people living with HIV (PLWH) with access to medical care are able to lead longer, healthier lives (Harrison et al., 2010). However, critical gaps in care persist along the HIV treatment cascade (e.g., Kay et al., 2016), which can include: (i) unknown HIV serostatus, (ii) limited access to and/or engagement in HIV-related care, (iii) limited access to and/or nonadherence to cART, and (iv) viremia (e.g., detectable HIV RNA in plasma). For example, although adherence to cART is essential for optimal health outcomes in HIV, including lower rates of virologic failure (e.g., Perno et al., 2002) and mortality (e.g., Lima et al., 2007), it is estimated that over 40% of PLWH are nonadherent to their medications (Ortego et al., 2011). Conceptual models underscore the many complexities of medication adherence in HIV (e.g., Barclay et al., 2007; Starace et al., 2006), which can be influenced by sociodemographic variables (e.g., age), psychiatric symptoms (e.g., apathy), health beliefs (e.g., attitudes toward medications), social factors (e.g., support), and environmental elements (e.g., compensatory strategies).

Neurocognitive impairment is another important predictor of nonadherence to cART (e.g., Hinkin et al., 2002). Successful medication adherence is a cognitively complex health behavior, which can involve (i) comprehension and learning of regimen instructions (e.g., dosing, timing, and special instructions), (ii) planning (e.g., ensuring adequate medications and related supplies are on hand at the prescribed dosing times), and (iii) memory (e.g., recalling the delayed intention to take the medication at the prescribed time) (Park & Meade, 2007). Approximately 30%–50% of PLWH meet criteria for an HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND; Heaton et al., 2010), which is commonly characterized by deficits in learning (e.g., Heaton et al., 2004), memory (e.g., Doyle et al., 2019), and executive functions (e.g., planning; Cattie et al., 2012). Indeed, deficits in learning and memory and executive functions are reliably and independently associated with increased risk of cART nonadherence in PLWH (e.g., Heaton et al., 2004; Obermeit et al., 2015). For example, a longitudinal study in 91 PLWH demonstrated that poorer performance on baseline executive function and learning/memory tasks was associated with lower medication adherence achieved after 6 months, whereas higher levels of medication adherence over 6 months were associated with improvements in a wide range of neurocognitive abilities, including executive functions (Ettenhofer et al., 2010). Notably, path analyses in that study revealed that executive function was the only domain for which a fully reciprocal relationship was observed with adherence, which suggests that it may play a primary role in perpetuating HIV-associated neurocognitive decline via medication nonadherence.

A critical component of successful HIV treatment adherence is medication management capacity, which refers to one’s ability to self-administer a medication regimen (Maddigan et al., 2003). Medication management capacity includes functional skills such as correctly identifying medications and selecting the proper timing and dose (MacLaughlin et al., 2005). Medication management capacity can be measured objectively using simulations that evaluate both “pill dispensing” (i.e., compliance with a dosage/regimen indicated by correct placement in a one-week pillbox) and “medication inference” (i.e., correct interpretation of a medication insert and dosing instructions). Although many cART regimens have been reduced in complexity to single medication combination formulas, polypharmacy is common (Edelman et al., 2013), and difficulties in medication management persist among PLWH. For example, Patton et al. (2012) reported that in a sample of 448 PLWH, 19% were impaired on a laboratory-based medication management task, which in turn was associated with suboptimal cART adherence among individuals with current immunosuppression. Medication management has also been associated with race/ethnicity, gender, education, and health literacy among PLWH (e.g., Waldrop-Valverde et al., 2009; Waldrop-Valverde, Osborn et al., 2010).

Poorer performance-based medication management capacity is consistently related to global neuropsychological impairment in PLWH (e.g., Gandhi et al., 2011; Heaton et al., 2004; Mindt et al., 2003; Patton et al., 2012; Thames et al., 2011, 2013). At the domain level, poorer performance-based medication management skills in HIV are associated with impairment in learning and memory, including verbal list learning (e.g., Albert et al., 1999; Thames et al., 2011, 2013). Moreover, medication management skills in PLWH are associated with a range of executive functions (e.g., Cooley et al., 2020), including planning (e.g., Cattie et al., 2012; Waldrop-Valverde, Jones et al., 2010), set shifting (e.g., Thames et al., 2011, 2013), and inhibition (e.g., Thames et al., 2011, 2013). In contrast, other neurocognitive domains, including motor skills and visuospatial abilities, are not reliably associated with medication management (e.g., Patton et al., 2012; Thames et al., 2013).

It is plausible that executive dysfunction may drive the deficits in the strategic aspects of learning and memory that, in turn, adversely affect performance-based medication management capacity in PLWH. At the level of theory, it is widely accepted that executive functions exert influence over encoding and retrieval of episodic memory (e.g., Moscovitch, 1992), which is supported by clinical studies of samples with executive dysfunction who show deficits in the organizational aspects of verbal learning (e.g., Stuss et al., 1994). HIV preferentially disrupts frontal-striatal-thalamic circuitry (e.g., Du Plessis et al., 2014), which supports executive functions (see Walker & Brown, 2018 for a review). Accordingly, HIV-associated impairments in learning and memory are often characterized by deficits in the strategic (i.e., executive) aspects of encoding and retrieval (e.g., Peavy et al., 1994). Approximately 30%–40% of PLWH demonstrate learning and memory impairments that are consistent with this mixed encoding and retrieval profile (e.g., Becker et al., 1995; Woods, Scott, Dawson et al., 2005), which is characterized by impaired learning and delayed recall in the setting of relatively better recognition performance (Delis, 2000). Rapid forgetting is less common among PLWH, although it is sometimes seen in HIV-associated dementia (HAD; Scott et al., 2006). PLWH are less likely to use higher-order encoding strategies (e.g., semantic clustering), which is associated with executive dysfunction and poorer overall learning and recall (e.g., Gongvatana et al., 2007). Hinkin et al. (2002) demonstrated that deficits in executive functions, learning/memory, and attention were associated with poor adherence at the univariable level; a follow-up logistic regression revealed that learning/memory remained the only significant predictor of adherence in a regression with six neurocognitive domains, including executive functions. Thus, learning might be one pathway by which executive dysfunction disrupts medication management and adherence.

Therefore, the present study aimed to clarify the nature of the relationships between executive functions, learning, and medication management in a sample of PLWH. First, we hypothesized that learning would mediate the relationship between executive functions and a laboratory task of medication management. In other words, we expected that the cognitive path from executive dysfunction to medication mismanagement would travel through learning. Since learning and executive functions share some neural systems and are often correlated, particularly when measured with clinical tests, we also examined the specificity of our model by testing an alternate model in which executive functions served as the mediator between learning and medication management, which was deemed unlikely based on the available theory and clinical evidence. This type of specificity analysis is commonly used in mediation, particularly for nonexperimental, cross-sectional studies in which the independent variable (i.e., executive functions) and the mediator (i.e., learning) have an established correlation. The logic of the strategy is that if the hypothesized sequential relationship between executive dysfunction, learning, and medication management is viable, then there should be a weaker (or null) statistical model when the independent variable and mediator are inverted. The specificity of the primary hypothesized model was also tested by replacing the hypothesized mediator (i.e., learning) with simple motor skills, which is not a viable downstream effect of executive functions and was therefore not expected to mediate the relationship between executive functions and medication management.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Two hundred and seven PLWH were recruited into the National Institutes of Health-funded study of aging and memory from HIV clinics and the local San Diego community. Per the design of the parent study (see Avci et al., 2016), participants were recruited into “younger” (aged 20 to 40) and “older” (aged 50 to 75) age cells. HIV serostatus was confirmed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or MedMira rapid tests. The study was approved by the institutional review board, and all participants provided written, informed consent. Any participants with a history of a severe psychiatric disorder (e.g., bipolar disorder, schizophrenia) or neurological condition (e.g., stroke, seizure disorder) were excluded from analyses. In addition, participants with an estimated IQ score less than 70 on the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (Wechsler, 2001), who tested positive for alcohol or illicit drugs (excluding marijuana) on the day of testing, or who met criteria for a current substance use disorder were also excluded. After excluding three participants with positive urine toxicology screens and nine participants with current substance use disorders, the final sample included 195 PLWH (85 “younger” and 110 “older”). Descriptive data for the study sample are provided in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

General descriptive data for the study sample (N = 195)

| Variable | M (SD) |

|---|---|

| Demographic | |

| Age (years) | 45.6 (13.5) |

| Education (years) | 13.6 (2.4) |

| Sex (% men) | 85.6 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Caucasian (%) | 54.9 |

| African American (%) | 23.6 |

| Hispanic (%) | 19.0 |

| Other (%) | 2.6 |

| Psychiatric | |

| Depression | |

| POMS depression/dejection (of 60) | 11.1 (12.7) |

| Current major depressive disorder (%) | 13.3 |

| Lifetime major depressive disorder (%) | 60.5 |

| Anxiety | |

| POMS tension/anxiety (of 36) | 9.75 (7.5) |

| Current anxiety disorder (%) | 11.2 |

| Lifetime anxiety disorder (%) | 32.8 |

| Lifetime substance use disorders (%) | 73.8 |

| Alcohol (%) | 56.9 |

| Cannabis (%) | 35.9 |

| Stimulant (%) | 45.1 |

| Opioid (%) | 11.3 |

| Other (%) | 23.6 |

| Medical | |

| HIV duration (years) | 12.7 (8.6) |

| AIDS (%) | 52.6 |

| CD4 count (cells/μL) | 584.0 (287.6) |

| Nadir CD4 Count (cells/μL) | 227.2 (185.7) |

| Plasma RNA detectable (%)a | 21.3 |

| Hepatitis C virus (%) | 20.7 |

| Number of prescribed medications | 6.9 (3.7) |

| Prescribed ART (%) | 89.7 |

| Cardiovascular comorbidities (no.)b | 0.6 (0.8) |

| SF-36 physical health (of 100) | 68.7 (23.0) |

Note: CD4 = cluster of differentiation 4; ART = antiretroviral therapy; POMS = Profile of Mood States; SF-36 = RAND 36-Item Short Form Health Survey.

a14.1% of persons on ART had detectable HIV RNA in plasma.

bCardiovascular comorbidities included self-reported diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, or coronary artery disease.

Table 2.

Neurocognitive data for the study sample (N = 195)

| Variable | M (SD) |

|---|---|

| WTAR verbal IQ | 101.2 (11.0) |

| HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (%) | 27.2 |

| Asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment (%) | 11.8 |

| Minor neurocognitive disorder (%) | 15.4 |

| HIV-associated dementia (%) | 0.0 |

| Executive functions | |

| Tower of London–Drexel version Total Moves | 34.8 (21.2) |

| Trail Making Test part B–part A (s) | 50.7 (40.4) |

| Digit Span backwards (of 14) | 6.7 (2.2) |

| Verbal fluency | |

| Letter B (no. of words) | 14.8 (4.6) |

| Actions (no. of words) | 15.7 (4.8) |

| Animals/Instruments (no. of correct switches) | 14.6 (3.5) |

| Learning | |

| CVLT-II Trials 1–5 (of 80) | 47.5 (9.7) |

| WMS-III Logical Memory I (of 75) | 40.4 (11.3) |

| Motor skills | |

| Grooved pegboard, dominant hand (s) | 74.7 (20.0) |

| Grooved pegboard, nondominant hand (s) | 81.9 (20.8) |

Note: CVLT-II = California Verbal Learning Test, 2nd Edition; WMS-III = Wechsler Memory Scale, 3rd Edition; WTAR = Wechsler Test of Adult Reading.

Medication Management

Medication management ability was measured with a modified version of the Medication Management Test-Revised (MMT-R; Heaton et al., 2004; Matchanova et al., 2019). In this laboratory task, participants were asked to dispense pills from four mock pill bottles to a medication organizer according to specific instructions. For example, a pill bottle might indicate that participants should take one pill, two times a day, at mealtimes. Participants received one point for each correctly dispensed medication, for an overall MMT-R score ranging from 0 to 4 (M = 3.4, SD = 1.0).

Neuropsychological Assessment

All participants underwent a comprehensive research neuropsychological assessment that was designed in accordance with the Frascati criteria for HAND (Antinori et al., 2007). As detailed in Tierney et al. (2017), this battery included well-validated clinical measures of neuropsychological function across seven domains and five measures of everyday functioning (not including the MMT-R). Table 2 shows the frequency of HAND diagnoses and raw scores on the neurocognitive measures used in this study.

Executive Functions

Executive functions were measured using the Tower of London Test–Drexel Edition (ToL; Culbertson & Zillmer, 2001), the Trail Making Test part B−part A (TMT; Reitan & Wolfson, 1985), digits backwards from the Digit Span subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-3rd Edition (WAIS-III; Wechsler, 1997a), verbal fluency (letter B; Delis et al., 2001 and actions; Woods, Scott, Sires et al., 2005), and animals/instruments switching (Delis et al., 2001). A composite executive functions score was calculated as the average sample-based raw z-score of ToL Total Moves, TMT part B–part A, Digit Span backwards, verbal fluency, and number of correct animal/instrument switches, such that higher z-scores corresponded to better executive functions (mean ρ = .32).

Verbal Learning

Participants completed the California Verbal Learning Test-2nd Edition (CVLT-II; Delis, 2000) and the Logical Memory subtest of the Wechsler Memory Scale-3rd Edition (WMS-III; Wechsler, 1997b).

Primary Learning Scores

The CVLT-II is a word list-learning task that includes five initial learning trials. During each trial, the examiner reads a list of 16 words which belong to four semantic categories, and participants are asked to repeat as many words as they can, in any order. Total learning is measured using the total number of correct words the participant produced over the five trials (CVLT-II Trials 1–5). The Logical Memory subtest of the WMS-III is a story-learning task in which the examiner reads two short stories aloud to the participant. After each story, participants are asked to repeat as much of the story as they can remember (Logical Memory I score). A composite performance-based learning score was calculated by converting the CVLT-II Trials 1–5 and Logical Memory I raw scores to sample-based z-scores and then averaging them (r = .43, p < .001).

CVLT-II Strategy Use

Follow-up analyses investigating strategy use during CVLT-II learning trials were conducted using the Semantic Clustering and Serial Clustering Forward scores from the CVLT-II manual. The semantic clustering index measures the extent to which the participant produced words grouped by semantic category, whereas the serial clustering forward index measures the extent to which the participant grouped words by the order in which they were presented.

Motor Skills

Motor skills were measured using the dominant and nondominant hand trials of the Grooved Pegboard test (Kløve, 1963). A composite motor skills score was calculated by converting total time for the dominant and nondominant hand trials to sample-based z-scores and then averaging them, such that higher z-scores corresponded to better performance (ρ = .79, p < .001).

Medical and Psychiatric Evaluation

All participants completed a neuromedical examination. Demographic information, including age, education, sex, and race/ethnicity were collected. HIV disease and other medical characteristics are provided in Table 1. Participants were asked to provide the number of medications they were currently taking, which included antiretroviral therapy as well as prescribed medications for non-HIV conditions. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI version 2.128; World Health Organization, 1998) was administered to determine the presence of depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders. Participants also completed the Profile of Mood States (McNair et al., 1981) and the RAND 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) and the RAND 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36; Ware & Sherbourne, 1992).

Data Analysis

A series of mediation models were conducted to evaluate the study hypotheses (see MacKinnon et al., 2007). Our primary mediation model was conducted using executive functions as the independent variable, verbal learning as the mediator, and MMT-R as the dependent variable. In these models, path (a) was the association between executive functions and learning, path (b) was the association between learning and medication management, path (c) was the total effect of executive functions on medication management, and path (c′) represented the direct effect between executive functions and the MMT-R while adjusting for the mediator. This model specifically examines whether the relationship between executive functions and medication management occurs (either fully or in part) by way of verbal learning. Next, a mediation model was conducted to confirm the directionality of the hypothesized effects by inverting executive functions and learning, which was expected to yield null findings based on the available theory and clinical evidence. A final mediation model was conducted to examine the specificity of the primary hypothesized effect by using motor skills as the mediator between executive functions and the MMT-R, which was also deemed unlikely to show significant effects because basic motor skills slowing would not be hypothesized as a downstream effect of executive dysfunction. All variables in Table 1 were examined as possible covariates for these, with inclusion criteria being significant univariable associations with executive functions, learning, and MMT-R at a critical alpha of .05. Only education was related to all three components of the model (all ps < .05) and was thus included as a covariate. Mediation models were analyzed in Mplus Version 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2017) using maximum likelihood estimation and the 95% confidence interval (CI) bootstrapping method. Results are unstandardized estimates. Partially standardized effect sizes were calculated to determine the magnitude of the mediation effects for a one-unit increase in executive functions. Since executive functions was calculated as a composite z-score, a one-unit increase in executive functions corresponded to a change of one sample-based SD. Planned post hoc Spearman’s rho correlations were conducted to determine the association of executive functions and MMT-R scores with Semantic and Serial Clustering scores on the CVLT-II.

Results

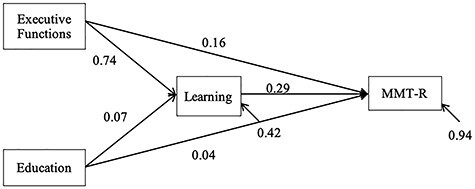

Correlations between the primary study variables are presented in Table 3 (NB., there was no significant difference between the older and younger participants in the magnitude of these correlations; all ps > .10). In the first mediation model, verbal learning was a significant mediator of the relationship between executive functions and MMT-R (95% CI [0.05, 0.39]; Fig. 1), after controlling for education. The partially standardized mediated effect size of learning was 0.21, indicating that for two individuals with the same level of education and a one SD difference in executive functions, the individual with better executive functions is expected to perform 0.21 SD units higher on the MMT-R through the mediating effect of learning. After controlling for the effects of verbal learning and education, executive functions did not have a significant direct effect on medication management (95% CI [−0.12, 0.45]).

Table 3.

Pearson correlations of study variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Medication Management Test-Revised | – | ||||

| 2. Executive functions | .26* | – | |||

| 3. Learning | .29* | .62* | – | ||

| 4. Motor skills | .23* | .33* | .31* | – | |

| 5. Education | .21* | .29* | .32* | .13 | – |

* p < .01.

Fig. 1.

Unstandardized bootstrap estimates for the model of learning as a mediator between executive functions and the Medication Management Test-Revised (MMT-R; N = 195).

Post hoc analyses revealed that better executive functions performance was associated with higher use of semantic clustering on the CVLT-II (ρ = .28, p < .001) but not with serial clustering (ρ = −.02, p = .817), and there was a significant difference between these correlations (two-tailed z = 2.11, p = .035). Better performance on the MMT-R was also associated with higher use of semantic clustering (ρ = .25, p < .001) but not with serial clustering (ρ = .02, p = .826), with a significant difference between these correlations (two-tailed z = 2.08, p = .038).

The second model, which was inverted and intended to address directionality, showed that executive functions did not mediate the relationship between learning and MMT-R (95% CI [−0.05, 0.21]), and the partially standardized mediated effect size was 0.07. There was a significant direct effect of learning on the MMT-R after controlling for executive functions and education (95% CI [0.06, 0.51]).

Finally, the third model demonstrated that motor skills did not significantly mediate the relationship between executive functions and the MMT-R (95% CI [−0.03, 0.13]), and the partially standardized mediated effect size was 0.05. In this model, there was a significant direct effect of executive functions on the MMT-R (95% CI [0.06, 0.60]).

Discussion

The present study investigated whether executive functions may exert their effects on simulated medication management capacity among PLWH by way of disrupting the strategic aspects of verbal learning. Executive dysfunction (as measured by planning, cognitive flexibility, working memory, and fluency) demonstrated a small-to-medium association with poorer medication management capacity (r = .26), consistent with previous studies (e.g., Heaton et al., 2004; Thames et al., 2013; Waldrop-Valverde, Jones, et al., 2010). Also commensurate with prior work (e.g., Heaton et al., 2004; Thames et al., 2013), poorer performance on verbal learning measures (i.e., list and story learning) demonstrated a small-to-medium association with lower medication management capacity (r = .29). Extending those studies and consistent with our a priori hypotheses, we also observed that learning, but not motor skills, significantly mediated the relationship between executive functions and medication management among PLWH. Indeed, the direct relationship between executive functions and simulated medication management was no longer significant after controlling for the mediating effect of learning. This mediation effect was associated with a small effect size, which might be expected given the small-to-medium direct associations of executive functions and learning with simulated medication management. Moreover, a test of the inverted model (i.e., whether executive functions mediated the relationship between learning and medication management) was null, supporting the robustness of the hypothesized directionality of this mediation model. Taken together, these data suggest that disrupted verbal learning appears to be a pathway by which executive dysfunction exerts its adverse effects on medication management capacity among PLWH.

Of course, verbal learning is not a unitary process; in the setting of HIV disease, deficits in the strategic aspects of encoding (e.g., less use of higher-order clustering) predominate (e.g., Gongvatana et al., 2007). Post hoc analyses revealed that better performance on executive functions tasks and the MMT-R were both associated with greater use of semantic, but not serial clustering during verbal list learning. In other words, executive functions were associated with the spontaneous use of higher-order strategies during a supra-span learning task, and the use of these higher-order strategies was related to better medication management capacity. Taken together, these findings suggest that PLWH with executive dysfunction may demonstrate difficulty in learning new information, potentially due to ineffective strategy use, and that this difficulty may in turn put them at a higher risk for problems managing their medications in the laboratory. Difficulties with executive functions and encoding and retrieval can also affect actual medication adherence in PLWH (e.g., Obermeit et al., 2015), but it remains to be determined whether learning is a mediator of real-world health behavior in this regard. Functional capacity may itself be a mediator of the relationship between cognition and medication adherence, as prior studies show small-to-medium associations between medication management capacity and real-world medication knowledge (e.g., Waldrop-Valverde et al., 2018) and adherence (e.g., Patton et al., 2012) in PLWH. These relationships are most reliable for biological (e.g., Cooley et al., 2020) and behavioral (e.g., Albert et al., 1999; Patton et al., 2012) measures of adherence, whereas self-report measures of adherence do not generally track well with medication management capacity in PLWH (e.g., Cooley et al., 2020; Thames et al., 2011). Of course, the path from a laboratory-based measure of medication management capacity to actual medication adherence is complex and can be influenced by a variety of additional psychological (e.g., attitudes toward medications), medical (e.g., side effects, disease severity), and environmental (e.g., fiscal) factors (Casaletto et al., 2017).

These results are clinically relevant to the understanding and potential remediation of medication management skills among PLWH with executive dysfunction. These findings suggest that PLWH with executive dysfunction may not only be impaired in the aspects of medication management traditionally thought to be associated with executive functions (e.g., planning out regimen, organizing pills), but may also demonstrate difficulty learning the instructions for proper medication management in organized and efficient ways. Interventions aimed at improving medication adherence in HIV have shown preliminary success, with a main focus on education about antiretroviral medication and motivational interviewing (e.g., Krummenacher et al., 2011; Parsons et al., 2005, 2007), but no studies to date have investigated interventions for medication adherence among PLWH with neurocognitive impairment. Therefore, future studies may wish to investigate how compensatory neurocognitive training (i.e., teaching participants how to use more effective learning strategies such as semantic clustering and personalization) may affect medication management among PLWH. Indeed, in a study of 1,401 older adults, memory training targeted at improving strategy use (e.g., organization, association, visualization) resulted in increased use of effective strategies both immediately and at a five-year follow-up (Gross & Rebok, 2011). Furthermore, pre-post training changes in strategy use mediated changes on an everyday functioning composite, including both self-report and performance-based measures (Gross & Rebok, 2011). Other approaches that take advantage of introducing “desirable difficulties” (Bjork, 1994) that are hypothesized to deepen encoding, including self-generation (Weber et al., 2012) and spaced retrieval practice (e.g., Avci et al., 2017) are also associated with improved learning and retention performance in PLWH and might be applicable to medication management skills.

The findings from this study are not without interpretive limitations. Because this was a cross-sectional study, it is not possible to conclude that declines in executive functions and learning are the direct cause of poor simulated medication management performance. Future longitudinal and experimental studies would be helpful in investigating this possibility and clarifying how medication management ability may change over time in PLWH with or without neurocognitive impairment (Ettenhofer et al., 2010). Several aspects of the study sample also limit the generalizability of the findings, including (i) The parent study prospectively recruited participants into persons in discordant age groups (≤40 and ≥ 50 years), thus findings may not be applicable to persons in their 40s (although age was not associated with MMT-R scores, p = .48); (ii) Approximately one-third of the sample met criteria for HAND, which is commensurate with epidemiological estimates (e.g., Heaton et al., 2010); however, no participant had HAD. Given that HAD commonly produces more severe encoding deficits (see Gongvatana et al., 2007 and Scott et al., 2006) and poorer functional capacity (Antinori et al., 2007), our observed findings may differ in more impaired samples (e.g., less skewed MMT-R distributions, decreased risk of Type II error for the specificity analyses); and (iii) the study sample was also predominately men and White, which may limit the generalizability of the findings, particularly given prior evidence that women and Black Americans may be at greater risk of poor medication management capacity (e.g., Waldrop-Valverde et al., 2009). We were also limited by the executive functions composite in this study, which included measures of planning, cognitive flexibility, working memory, and fluency, but not novel problem-solving or inhibition, which have shown associations with medication management (e.g., Ettenhofer et al., 2010). The participants in this study performed quite well on the MMT-R (range = 0–4, M = 3.4), leading to a negatively skewed distribution of medication management skills. Although the mediating effect of learning was significant despite this skewed distribution, future studies using more challenging medication management tasks, or measures of real-world medication adherence (e.g., Medication Event Monitoring System), may provide further information regarding this effect. Nonetheless, results of this study suggest that the contributions of executive functions to learning ability may be important in medication management capacity of PLWH.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Marizela Verduzco for study coordination, Dr Scott Letendre for overseeing the neuromedical aspects of the parent project, Dr J. Hampton Atkinson and Jennifer Marquie Beck for participant recruitment, and Donald R. Franklin and Stephanie Corkran for data processing.

Contributor Information

Kelli L Sullivan, Department of Psychology, University of Houston, Houston, TX, USA.

Michelle A Babicz, Department of Psychology, University of Houston, Houston, TX, USA.

Steven Paul Woods, Department of Psychology, University of Houston, Houston, TX, USA.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers R01-MH073419, P30-MH62512].

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Albert, S. M., Weber, C. M., Todak, G., Polanco, C., Clouse, R., McElhiney, M.et al. (1999). An observed performance test of medication management ability in HIV: Relation to neuropsychological status and medication adherence outcomes. AIDS and Behavior, 3(2), 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Antinori, A., Arendt, G., Becker, J. T., Brew, B. J., Byrd, D. A., Cherner, M.et al. (2007). Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology, 69, 1789–1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avci, G., Loft, S., Sheppard, D. P., Woods, S. P., & HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program (HNRP) Group. (2016). The effects of HIV disease and older age on laboratory-based, naturalistic, and self-perceived symptoms of prospective memory: does retrieval cue type and delay interval matter? Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition, 23(6), 716–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avci, G., Woods, S. P., Verduzco, M., Sheppard, D. P., Sumowski, J. F., Chiaravalloti, N. D.et al. (2017). Effect of retrieval practice on short-term and long-term retention in HIV+ individuals. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 23(3), 214–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay, T. R., Hinkin, C. H., Castellon, S. A., Mason, K. I., Reinhard, M. J., Marion, S. D.et al. (2007). Age-associated predictors of medication adherence in HIV-positive adults: Health beliefs, self-efficacy, and neurocognitive status. Health Psychology, 26(1), 40–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker, J. T., Caldararo, R., Lopez, O. L., Dew, M. A., Dorst, S. K., & Banks, G. (1995). Qualitative features of the memory deficit associated with HIV infection and AIDS: Cross-validation of a discriminant function classification scheme. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 17(1), 134–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjork, R. A. (1994). Memory and metamemory considerations in the training of human beings. In Metcalfe, J., & Shimamura, A. (Eds.), Metacognition: Knowing about knowing (, pp. 185–205). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Casaletto, K. B., Weber, E., Iudicello, J. E., & Woods, S. P. (2017). Real-world impact of HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment. In Chiaravalloti, N., & Goverover, Y. (Eds.), Changes in the Brain, Impact on Daily Life (, pp. 211–245). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Cattie, J. E., Doyle, K., Weber, E., Grant, I., Woods, S. P., & HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program (HNRP) Group (2012). Planning deficits in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders: Component processes, cognitive correlates, and implications for everyday functioning. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 34(9), 906–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley, S. A., Paul, R. H., & Ances, B. A. (2020). Medication management abilities are reduced in older persons living with HIV compared with healthy older HIV- controls. Journal of Neurovirology, 26, 264–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culbertson, W. C., & Zillmer, E. (2001). Tower of London-Drexel University (TOLDX). North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Delis, D. C. (2000). CVLT-II: California Verbal Learning Test: Adult version. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Delis, D. C., Kaplan, E., & Kramer, J. H. (2001). Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS). San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Du Plessis, S., Vink, M., Joska, J. A., Koutsilieri, E., Stein, D. J., & Emsley, R. (2014). HIV infection and the fronto–striatal system: A systematic review and meta-analysis of fMRI studies. AIDS, 28(6), 803–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, K. L., Woods, S. P., McDonald, C. R., Leyden, K. M., Holden, H. M., E. Morgan, E., ... & Corey-Bloom, J. (2019). Verbal episodic memory profiles in HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorders (HAND): A comparison with Huntington's disease and mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Applied Neuropsychology: Adult, 26(1), 17–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelman, E. J., Gordon, K. S., Glover, J., McNicholl, I. R., Fiellin, D. A., & Justice, A. C. (2013). The next therapeutic challenge in HIV: Polypharmacy. Drugs & Aging, 30(8), 613–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettenhofer, M. L., Foley, J., Castellon, S. A., & Hinkin, C. H. (2010). Reciprocal prediction of medication adherence and neurocognition in HIV/AIDS. Neurology, 74(15), 1217–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi, N. S., Skolasky, R. L., Peters, K. B., Moxley, R. T., Creighton, J., Roosa, H. V.et al. (2011). A comparison of performance-based measures of function in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Journal of Neurovirology, 17(2), 159–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gongvatana, A., Woods, S. P., Taylor, M. J., Vigil, O., & Grant, I. (2007). Semantic clustering inefficiency in HIV-associated dementia. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 19(1), 36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross, A. L., & Rebok, G. W. (2011). Memory training and strategy use in older adults: Results from the ACTIVE study. Psychology and Aging, 26(3), 503–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, K. M., Song, R., & Zhang, X. (2010). Life expectancy after HIV diagnosis based on national HIV surveillance data from 25 states, United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 53(1), 124–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton, R. K., Marcotte, T. D., Mindt, M. R., Sadek, J., Moore, D. J., Bentley, H.et al. (2004). The impact of HIV-associated neuropsychological impairment on everyday functioning. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 10, 317–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton, R. K., Clifford, D. B., Franklin, D. R., Woods, S. P., Ake, C., Vaida, F.et al. (2010). HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy CHARTER study. Neurology, 75(23), 2087–2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkin, C. H., Castellon, S. A., Durvasula, R. S., Hardy, D. J., Lam, M. N., Mason, K. I.et al. (2002). Medication adherence among HIV+ adults: Effects of cognitive dysfunction and regimen complexity. Neurology, 59(12), 1944–1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay, E. S., Batey, D. S., & Mugavero, M. J. (2016). The HIV treatment cascade and care continuum: Updates, goals, and recommendations for the future. AIDS Research and Therapy, 13(1), 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kløve, H. (1963). Grooved pegboard. Lafayette, IN: Lafayette Instruments. [Google Scholar]

- Krummenacher, I., Cavassini, M., Bugnon, O., & Schneider, M. P. (2011). An interdisciplinary HIV-adherence program combining motivational interviewing and electronic antiretroviral drug monitoring. AIDS Care, 23(5), 550–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima, V. D., Geller, J., Bangsberg, D. R., Patterson, T. L., Daniel, M., Kerr, T.et al. (2007). The effect of adherence on the association between depressive symptoms and mortality among HIV-infected individuals first initiating HAART. AIDS, 21(9), 1175–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon, D. P., Fairchild, A. J., & Fritz, M. S. (2007). Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 593–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLaughlin, E. J., Raehl, C. L., Treadway, A. K., Sterling, T. L., Zoller, D. P., & Bond, C. A. (2005). Assessing medication adherence in the elderly. Drugs & Aging, 22(3), 231–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddigan, S. L., Farris, K. B., Keating, N., Wiens, C. A., & Johnson, J. A. (2003). Predictors of older adults’ capacity for medication management in a self-medication program: A retrospective chart review. Journal of Aging and Health, 15(2), 332–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matchanova, A., Woods, S. P., & Kordovski, V. M. (2019). Operationalizing and evaluating the Frascati criteria for functional decline in diagnosing HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders in adults. Journal of Neurovirology, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNair, D. M., Lorr, M., & Droppleman, L. F. (1981). Manual for the Profile of Mood States. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Services. [Google Scholar]

- Mindt, M. R., Cherner, M., Marcotte, T. D., Moore, D. J., Bentley, H., Esquivel, M. M.et al. (2003). The functional impact of HIV-associated neuropsychological impairment in Spanish-speaking adults: A pilot study. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 25(1), 122–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscovitch, M. (1992). Memory and working-with-memory: A component process model based on modules and central systems. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 4, 257–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998-2017). Mplus User’s Guide (Eighth ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Obermeit, L. C., Morgan, E. E., Casaletto, K. B., Grant, I., Woods, S. P., & HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program (HNRP) Group (2015). Antiretroviral non-adherence is associated with a retrieval profile of deficits in verbal episodic memory. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 29(2), 197–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortego, C., Huedo-Medina, T. B., Llorca, J., Sevilla, L., Santos, P., Rodríguez, E.et al. (2011). Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART): A meta-analysis. AIDS and Behavior, 15(7), 1381–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, D. C., & Meade, M. L. (2007). A broad view of medical adherence: Integrating cognitive, social, and contextual factors. In Park, D. C., & Liu, L. L. (Eds.), Medical adherence and aging: Social and cognitive perspectives (, pp. 3–21). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, J. T., Golub, S. A., Rosof, E., & Holder, C. (2007). Motivational interviewing and cognitive-behavioral intervention to improve HIV medication adherence among hazardous drinkers: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 46(4), 443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, J. T., Rosof, E., Punzalan, J. C., & Maria, L. D. (2005). Integration of motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral therapy to improve HIV medication adherence and reduce substance use among HIV-positive men and women: Results of a pilot project. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 19(1), 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton, D. E., Woods, S. P., Franklin, D., Cattie, J. E., Heaton, R. K., Collier, A. C.et al. (2012). Relationship of medication management test-revised (MMT-R) performance to neuropsychological functioning and antiretroviral adherence in adults with HIV. AIDS and Behavior, 16(8), 2286–2296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peavy, G., Jacobs, D., Salmon, D. P., Butters, N., Delis, D. C., Taylor, M.et al. (1994). Verbal memory performance of patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: Evidence of subcortical dysfunction. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 16(4), 508–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perno, C. F., Ceccherini-Silberstein, F., De, A. L., Cozzi-Lepri, A., Gori, C., Cingolani, A.et al. (2002). Virologic correlates of adherence to antiretroviral medications and therapeutic failure. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 31, S118–S122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan, R. M., & Wolfson, D. (1985). The Halstead-Reitan neuropsychological test battery: Theory and clinical interpretation (, Vol. 4). Tucson, AZ: Reitan Neuropsychology. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J. C., Woods, S. P., Patterson, K. A., Morgan, E. E., Heaton, R. K., Grant, I.et al. (2006). Recency effects in HIV-associated dementia are characterized by deficient encoding. Neuropsychologia, 44(8), 1336–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starace, F., Massa, A., Amico, K. R., & Fisher, J. D. (2006). Adherence to antiretroviral therapy: An empirical test of the information-motivation-behavioral skills model. Health Psychology, 25(2), 153–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuss, D. T., Alexander, M. P., Palumbo, C. L., Buckle, L., Sayer, L., & Pogue, J. (1994). Organizational strategies of patients with unilateral or bilateral frontal lobe injury in word list learning tasks. Neuropsychology, 8, 35–373. [Google Scholar]

- Thames, A. D., Arentoft, A., Rivera-Mindt, M., & Hinkin, C. H. (2013). Functional disability in medication management and driving among individuals with HIV: A 1-year follow-up study. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 35(1), 49–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thames, A. D., Kim, M. S., Becker, B. W., Foley, J. M., Hines, L. J., Singer, E. J.et al. (2011). Medication and finance management among HIV-infected adults: The impact of age and cognition. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 33(2), 200–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tierney, S., Sheppard, D. P., Kordovski, V., Faytell, M., Avci, G., & Woods, S. P. (2017). A comparison of the sensitivity, stability, and reliability of three diagnostic schemes for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Journal of Neurovirology, 23, 404–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop-Valverde, D., Jones, D. L., Jayaweera, D., Gonzalez, P., Romero, J., & Ownby, R. L. (2009). Gender differences in medication management capacity in HIV infection: The role of health literacy and numeracy. AIDS and Behavior, 13(1), 46–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop-Valverde, D., Jones, D. L., Gould, F., Kumar, M., & Ownby, R. L. (2010). Neurocognition, health-related reading literacy, and numeracy in medication management for HIV infection. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 24(8), 477–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop-Valverde, D., Murden, R. J., Guo, Y., Holstad, M., & Ownby, R. L. (2018). Racial disparities in HIV antiretroviral medication management are mediated by health literacy. Health Literacy Research and Practice, 2, 205–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop-Valverde, D., Osborn, C. Y., Rodriguez, A., Rothman, R. L., Kumar, M., & Jones, D. L. (2010). Numeracy skills explain racial differences in HIV medication management. AIDS and Behavior, 14(4), 799–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, K. A., & Brown, G. G. (2018). HIV-associated executive dysfunction in the era of modern antiretroviral therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 40(4), 357–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware, J. E., Jr., & Sherbourne, C. D. (1992). The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care, 30, 473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber, E., Woods, S. P., Kellogg, E., Grant, I., Basso, M. R., & HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program (HNRP) Group (2012). Self-generation enhances verbal recall in individuals infected with HIV. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 18(1), 128–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D. (1997a). WAIS-III, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale: Administration and scoring manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D. (1997b). WMS-III: Wechsler Memory Scale administration and scoring manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D. (2001). Wechsler Test of Adult Reading. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (1998). Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI, version 2.1). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, S. P., Scott, J. C., Dawson, M. S., Morgan, E. E., Carey, C. L., Heaton, R. K.et al. (2005). Construct validity of Hopkins verbal learning test—Revised component process measures in an HIV-1 sample. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 20(8), 1061–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods, S. P., Scott, J. C., Sires, D. A., Grant, I., Heaton, R. K., Tröster, A. I.et al. (2005). Action (verb) fluency: Test–retest reliability, normative standards, and construct validity. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 11(4), 408–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]