Dear Editor,

In the article “Clinical application of a rapid antigen test for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 infection in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients evaluated in the emergency department: A preliminary report.”,1 Turcato et al. presented a study on the use of rapid antigenic tests (Ag-RDTs) instead of the usual real time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay to detect the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in the context of Emergency Departments (ED). They observed a general good sensitivity and specificity, lower in the subgroup of asymptomatic patients. Their conclusion is in favour of the use of Ag-RDTs in EDs as an additional tool to address the challenge of containing the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

We agree with the authors that the development of reliable but cheaper and faster point-of-care diagnostic tests was expected to be useful either for population-screening or as first aid tests in the emergency room.2 , 3 Data on the sensitivity and specificity of currently available Ag-RDTs derive from studies that vary in design, setting, population and type of specimen, thus strongly limiting the comparability and ability to make general inferences. Sensitivity appears to be highly variable, ranging from 29 to 94% compared to the RT-PCR test, but specificity is consistently high (>97%).[4], [5], [6], [7] Ag-RDTs were found to perform better in patients with high viral loads (Ct values ≤25 or >106 genomic virus copies/mL)5 , 7 , 8 which usually happens in the pre-symptomatic (0.5–3 days before symptom onset) and early symptomatic phases of the illness (within the first week from symptom onset) but limited data are available about other possible individual modifiers of the accuracy of the assay. A recent Cochrane review highlighted that patients’ characteristics were not available or poorly detailed in many studies, with only three out of 22 studies coming from an ED setting.8

Between October 26th and November 10th 2020, 455 patients accessed the ED of San Luigi Gonzaga University Hospital in Orbassano (Turin, Italy) and 324 underwent both RT-PCR and Ag-RDT testing. This period corresponds to the first two weeks of the second pandemic wave, with a weekly incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the Region of about 500 confirmed cases/100,000 inhabitants. Data were obtained as part of an observational study described elsewhere9 and a detailed presentation of methods is available in supplementary material.

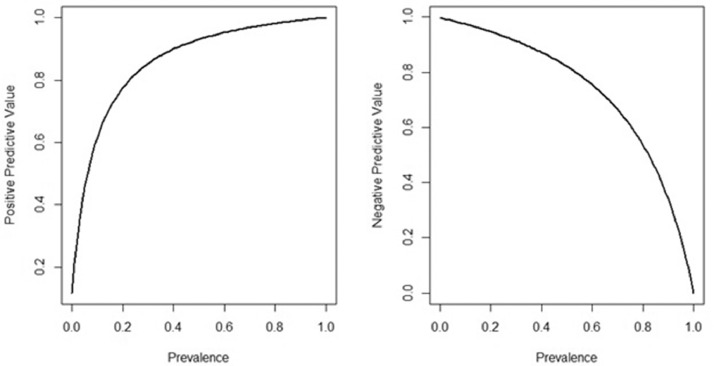

The prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in this cohort was 65% measured using RT-PCR as a gold standard. Supplementary Table 1 reports test results: 275 (84%) patients showed concordant results (168 positive and 107 negative), while 49 (15%) showed discordant results (42 patients had a positive RT-PCR and a negative Ag-RDT and 7 vice versa). Cohen's Kappa Statistics (k = 0.68 – 95% CI 0.61–0.77) highlighted substantial agreement. Specificity and sensitivity of Ag-RDT were 0.939 (95% CI: 0.895–0.983) and 0.800 (95% CI: 0.746–0.854), respectively, taking RT-PCR as the reference. Overall, the Ag-RDT positive predictive value was 0.960 (95% CI 0.931–0.989), and the negative predictive value was 0.718 (95% CI: 0.646–0.790). The variation of positive and negative predictive values due to difference in prevalence can be observed in Supplementary Table 2 and Fig. 1 . Positive predictive value could vary from 0.12, when the prevalence of the disease is 0.01, to 0.77 when the prevalence is 0.20. The negative predictive value could vary from about 1, considering a low prevalence (0.01) to 0.95, considering a higher prevalence (0.20).

Fig. 1.

Positive and negative predictive value estimates in relation to prevalence, using the sensitivity and specificity of the test found in our population (sensitivity = 0.800; specificity = 0.939).

No difference in patients’ characteristics between true positive and false negative tests was observed (Supplementary Table 3). On the contrary, false negative patients were significantly younger and they were tested significantly later after symptoms onset compared with true negative patients (Table 1 ). Moreover, fever (64.3% vs 19.6%, p < 0.0001) and cough (42.9% vs 15.0%, p = 0.0003) were significantly more frequent in false than true negatives, while chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was more frequent in true than false negatives, with a borderline significance (16.5% vs 4.8%, p = 0.06). Few true negative patients had bilateral pneumonia (n = 10, 9.4%), that was highly present in false negative patients (n = 25, 61.0%, p-value for difference < 0.0001) and multivariable analysis confirm these results, suggesting that wrong group allocation for negative patients occurred more frequently in patients with fever, cough, and pneumonia, while it was less likely in patients with COPD.

Table 1.

Ag-RDT negative patients: comparison of patients’ characteristics between true negative and false negative patients. Wilcoxon sum rank test (quantitative variables) and chi-square or Fisher's exact test (qualitative variables) are used and multivariable logistic model (including significant variables) to evaluate the association between being a false negative and patients’ characteristics.

| True negative (n = 107)Mean (SD), medianor Frequency (%) | False negative (n = 42)Mean (SD), medianor Frequency (%) | P-values | OR(95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 68.4 (18.6), med: 74.4 | 63.1 (16.3), med: 64.4 | 0.03 | For 1 year increase1.00 (0.96 – 1.03) |

| Days from symptoms onset | 3.9 (6.7), med: 2 | 6.3 (4.7), med: 6 | 0.0003 | For 1 day increase1.06 (0.97 – 1.16) |

| NEWS at arrival | 2.1 (3.0), med: 1 | 2.4 (2.5), med: 2 | 0.14 | |

| Symptoms | ||||

| Fever | 21 (19.6%) | 27 (64.3%) | <0.0001 | 4.31 (1.30 – 14.28) |

| Cough | 16 (15.0%) | 18 (42.9%) | 0.0003 | 5.72 (1.63 – 20.07) |

| Dyspnoea | 33 (30.8%) | 16 (38.1%) | 0.40 | |

| Respiratory failure | 16 (15.1%) | 8 (19.1%) | 0.56 | |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 29 (27.1%) | 7 (16.7%) | 0.18 | |

| Anosmia | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (4.8%) | 0.07* | |

| Ageusia | 6 (5.6%) | 3 (7.1%) | 0.72 | |

| Asthenia | 15 (14.0%) | 11 (26.2%) | 0.08 | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Obesity | 5 (6.2%) | 1 (2.8%) | 0.66* | |

| Hypertension | 43 (41.7%) | 13 (31.0%) | 0.22 | |

| Diabetes | 17 (16.5%) | 5 (11.9%) | 0.48 | |

| Heart disease | 26 (25.2%) | 7 (16.7%) | 0.26 | |

| COPD | 17 (16.5%) | 2 (4.8%) | 0.06* | 0.12 (0.01 – 1.29) |

| Cancer | 18 (17.5%) | 4 (9.5%) | 0.31* | |

| immunosuppression | 8 (7.8%) | 1 (2.4%) | 0.45* | |

| neurological disease | 14 (13.7%) | 4 (9.5%) | 0.59* | |

| Pneumonia | ||||

| No | 87 (82.1%) | 12 (29.3%) | <0.0001 | Reference |

| Monolateral | 9 (8.5%) | 4 (9.8%) | 4.12 (0.59 – 28.60) | |

| Bilateral | 10 (9.4%) | 25 (61.0%) | 14.89(4.14 – 53.52) | |

Fisher's exact test.

The infection prevalence and the clinical context where the test is used affect the effectiveness of the test itself10: the ideal test in a crowded ED context should help in identifying asymptomatic patients arriving to the ED for reasons other than COVID-19, who are concurrently found COVID-19 positive.

Our results suggest that a negative Ag-RDT test should not exclude COVID-19 in patients that clinically have symptoms that are strongly suggestive of COVID-19. Ag-RDTs alone had a low negative predictive value (we cannot trust a negative result of the test), thus they need to be evaluated in association with clinical judgement. A high level of suspicion should be maintained in patients with fever, cough or pneumonia notwithstanding a negative Ag-RDT. Since the predictive value is strictly related to the prevalence of disease, and then to the pre-test odds, Ag-RDTs are not really useful in settings where the prevalence of disease is high or in patients with high pre-test odds. On the contrary, in periods with low prevalence of the disease or in patients with a low pre-test odds (asymptomatic) or with symptoms probably related to a known COPD, Ag-RDTs can be used alone and we can trust a negative result.

In conclusion, our results confirm the limits of antigenic tests as first line screening tests in settings with high prevalence of disease or in patients with high pre-test odds, where a negative test is not informative (i.e. in ED in a pandemic period). This suggests that in these situations the antigenic test should be integrated in a clinical algorithm.

Declaration of Competing Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank Marco Alvich, Rebecca Tasca, Sara Roetti, and Selene Demaria for their help in collecting data.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2021.05.012.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Turcato G., Zaboli A., Pfeifer N., Ciccariello L., Sibilio S., Tezza G. Clinical application of a rapid antigen test for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 infection in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients evaluated in the emergency department: a preliminary report. J Infect. 2021;82(3):e14–e16. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cerutti F., Burdino E., Milia M.G., Allice T., Gregori G., Bruzzone B. Urgent need of rapid tests for SARS CoV-2 antigen detection: evaluation of the SD-Biosensor antigen test for SARS-CoV-2. J ClinVirol. 2020;132 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Candel F.J., Barreiro P., San Román J. Recommendations for use of antigenic tests in the diagnosis of acute SARS-CoV-2 infection in the second pandemic wave: attitude in different clinical settings. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2020;33(6):466–484. doi: 10.37201/req/120.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mak G.C., Cheng P.K., Lau S.S. Evaluation of rapid antigen test for detection of SARS-CoV-2 virus. J Clin Virol. 2020;129 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Omi K., Takeda Y., Mori M. SARS-CoV-2 qRT-PCR Ct value distribution in Japan and possible utility of rapid antigen testing kit. medRxiv. 2020:2020.06.16.20131243. 12.

- 6.Weitzel T., Legarraga P., Iruretagoyena M., et al. Head-to-head comparison of four antigen-based rapid detection tests for the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 in respiratory samples. bioRxiv. 2020:2020.05.27.119255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Scohy A., Anantharajah A., Bodéus M., Kabamba-Mukadi B., Verroken A., Rodriguez-Villalobos H. Low performance of rapid antigen detection test as frontline testing for COVID-19 diagnosis. J ClinVirol. 2020;129 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dinnes J., Deeks J.J., Adriano A. Cochrane COVID-19 diagnostic test accuracy group. Rapid, point-of-care antigen and molecular-based tests for diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;8 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caramello V., Macciotta A., De Salve A.V. Clinical characteristics and management of COVID-19 patients accessing the emergency department in a hospital in Northern Italy in March and April 2020. Epidemiol Prev. 2020;44(5–6 Suppl 2):208–215. doi: 10.19191/EP20.5-6.S2.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linares M., Pérez-Tanoira R., Carrero A. Panbio antigen rapid test is reliable to diagnose SARS-CoV-2 infection in the first 7 days after the onset of symptoms. J ClinVirol. 2020;133 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.