1. Introduction

The Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003, avian influenza H5N1 in 2005, swine influenza H1N1 in 2009 and H7N9 in 2013, Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014, Zika outbreak in Oceania in 2007 and 2015 in South America, Central America, Africa, and Asia were some of the most high profile infectious diseases that resulted in epidemics or pandemics since 2000 (Gold et al., 2019).

Hall et al. (2020) suggest that several pandemics have been ‘normalised’ and they are part of the global health business as usual. They argue that past pandemics have not become significant transition events despite the significant economic, tourism and social impacts. None of the past epidemics and pandemics experienced such an extensive reaction with lockdowns and travel restrictions as those that have been imposed for COVID-19. Unlike the aforementioned epidemics/pandemics, COVID-19 has extended to more than 200 countries and has brought significant changes to day-to-day life on a global scale, to the world economy and to society. Air transport has played a pivotal role in its expeditious transmission.

A number of papers have researched aviation system disruptions, even though the overall assessment of such events could arguably have gone further (e.g. see Tanrıverdi et al., 2020). Chen et al. (2017) measured the economic consequences of terrorist attacks, Corbet et al. (2019) analysed the traffic effects of terrorist attacks in Europe, Akyildirim et al. (2020) investigated the effects of airline disasters on aviation stocks and Reichardt et al. (2019) researched the impacts of natural disasters. Despite infectious diseases having an effect on traffic similar to that of terrorist attacks and natural disasters, the overall response of the aviation industry as well as the extent of the impact is different. Brownstein et al. (2006), Grais et al. (2003) and Fadel et al. (2008) researched the impact of influenza outbreaks, Chung (2015) examined the impact of pandemic outbreaks on airport businesses and Loh (2006) studied the impact of SARS on airlines. Yet, none of these infectious diseases developed into a global pandemic with such a wide geographical coverage as COVID-19.

Soon after the realisation that COVID-19 was a global concern, a number of air transport related academic papers were published on air travel restrictions (e.g. Chinazzi et al., 2020; Nikolaou and Dimitriou, 2020), aviation policy (Macilree and Duval, 2020), current and future demand (Suau-Sanchez et al., 2020; Lamb et al., 2020; Gudmundsson et al., 2020), impacts on aviation (e.g. Gössling et al., 2020; Iacus et al., 2020), implications for aircraft operators (Albers and Rundshagen, 2020; Budd et al., 2020) and airports (e.g. Serrano and Kazda, 2020; Forsyth et al., 2020). Yet, considering the impact of COVID-19 on the aviation industry and the current uncertainty, more empirical research is needed.

The Chinese market is one of the strongest in the aviation system and was the first one to be impacted. Li (2020) suggests that COVID-19 has a different influence on the Chinese market. Zhang et al. (2020a) investigated the risk of importing COVID-19 cases by foreign countries on Chinese provinces; they have not evaluated the traffic related implications to airlines and airports in China. Sun et al. (2020) provided a timely analysis of the network structures post COVID-19. Their spatial-temporal evolutionary dynamics approach looked at China, Europe and United States. Li (2020) focused on the cargo market and Czerny et al. (2020) examined the Chinese government's aviation policy choices in the light of the coronavirus pandemic. Meanwhile Zhang et al. (2020b) adopted a wider focus and examined the roles of different transport modes (air as well as high speed train and coach) in the spread of COVID-19 pandemic across Chinese cities.

The purpose of this paper is complementary to other Chinese research as it delves deeper into the Chinese market and provides an insight into the implications for specific airlines and airports. It aims to analyse air transport capacity, traffic and revenue changes in domestic and international markets involving China with a unique detailed and in-depth focus not seen in other related research in order to determine potentialities of market recovery within different market settings, namely for the three major Chinese markets (domestic, Europe and rest of Asia). This is broken down into three objectives:

-

•

An examination of seats offered and passengers flown through time, by selected routes and airlines

-

•

An assessment of revenues and average air fares through time, by selected routes, airlines and trends in class (economy, premium)

-

•

An investigation into changes in frequencies through time at the largest Chinese airports

Section 2 will discuss the literature underpinning impact studies of external and extraneous events with a focus on epidemics/pandemics, section 3 will summarise the methodology, section 4 details the impact analysis results and section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Infectious diseases and air transport

2.1. Travel restrictions as a response to infectious diseases

Isolation and quarantining have been effective tools in the fight against infectious diseases. Border controls and travel restrictions are usually imposed to constrain outbreaks. Travel restrictions aim to limit importation, i.e. tourists who were infected during their travels in the affected areas and brought the virus to the unaffected areas during their incubation or infectious period, and exportation, i.e. infected residents from affected areas travelling to unaffected areas during their incubation or infectious period (Luo et al., 2020). Air travel enables the rapidity of communicable disease transfer across international borders (Fadel et al., 2008) though cross-border travel by other modes (e.g. rail, road) can also lead to the rapid imported transmission of cases.

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 outbreak, with its epicentre in Wuhan, China, a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) (Lau et al., 2020b). Consequently, the Hubei province was placed under lockdown approximately three weeks after the start of COVID-19 outbreak. Lau et al. (2020a) compared domestic and international passenger volumes and routes of China to the distribution of domestic and international COVID-19 cases and found that there is a strong linear correlation within China and a significant correlation between international COVID-19 cases and passenger volumes. Cooper et al. (2006) and Keogh-Brown and Smith (2008) suggest that border closures are an expensive and ineffective outbreak control measure. With low vaccination rates and new virus variants, social distancing, which includes quarantine and travel restrictions is the main tool used. Some countries reacted by completely and immediately shutting down their borders and restricting flights to and from affected areas and others took fewer measures, implementing a 14-day self-quarantine for incoming travellers.

Quarantining infected individuals cannot successfully reduce the prevalence of pandemics without controlling international and domestic travel. International air travel can accelerate the spread of infectious diseases. Hufnagel et al. (2004) studied the spread of SARS and found that the isolation of large cities can be an effective epidemic control measure, but Cooper et al. (2006) in their study on influenza found this does not apply equally to influenza that has a much shorter serial interval than SARS. Tuncer and Le (2014) used a two-city dispersal model to predict the spread of avian influenza from Asia and Australia to major US cities via air travel and found that the effectiveness of control measures (e.g. quarantine and vaccination) depends strongly on the air travel rate. Brownstein et al. (2006) found that a decrease in domestic and international air travel was associated with a delayed and prolonged influenza season. Cooper et al. (2006) suggest that under most scenarios of air travel restrictions that they tested there is little value in delaying epidemics, unless almost all travel ceases very soon after epidemics are detected. Grais et al. (2003) suggest that the time lag for public health intervention is very short and coordinated pandemic planning is vital.

Cooper et al. (2006) argue that the rapid initial rate of growth of the epidemic in each city and the large number of people infected can make travel restrictions a relatively ineffective control measure. Lau et al. (2020b) argue that while the COVID-19 spread could not be contained, the lockdown in Hubei aided in slowing the speed of infection and reduced the correlation of domestic air traffic with COVID-19 cases within China. Lau et al. (2020b) believe that it is not feasible to contain the global spread of COVID-19, especially when considering political willingness and feasibility constraints to implement drastic countermeasures with tremendous social and economic consequences.

2.2. Impact of infectious diseases on travel and tourism

Transportation networks are fundamental for the movement of people and goods in the globalised economy, but external shocks have demonstrated their vulnerability (Corbet et al., 2019). The economic impact of SARS was of global concern (Keogh-Brown and Smith, 2008) and its effect on travel and tourism is researched by various scholars (Kuo et al., 2008; Dwyer et al., 2006; Loh, 2006; Zeng et al., 2005; Henderson, 2004; McKercher and Chon, 2004; Pine and McKercher, 2004).

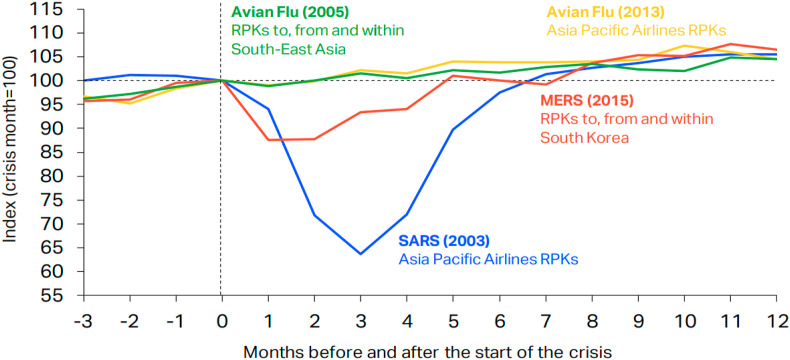

Zeng et al. (2005) suggest that tourism exhibits little resistance, but considerable resilience. Similarly, air transport is hugely impacted by shocks, disasters and epidemics, but its recovery period and type of effects differs depending on the nature, intensity and duration of the shock (Corbet et al., 2019). During the SARS epidemic of 2003, traffic dropped significantly. IATA Economics (2020a) suggests that the SARS epidemic had a serious impact on traffic volumes for Asia/Pacific based carries (Fig. 1 ). In 2003, Asia-Pacific airlines lost US$6 billion after seeing a reduction of 8% in Revenue Passenger Kilometres (RPKs), and 35% reduction at the peak of outbreak in May 2003.

Fig. 1.

Impact of past epidemiological outbreaks on aviation (Source: IATA Economics, 2020a).

© International Air Transport Association, 2020. [What can we learn from past pandemic episodes?]. All Rights Reserved. Available on IATA Economics page.

The effect of SARS on the Chinese economy was short, but extreme (Zeng et al., 2005). The SARS crisis lasted five months with 5329 patients in China, 8098 cases worldwide and 774 deaths worldwide, whereas COVID-19 confirmed cases as of the March 4, 2021 were 89,000 (4636 deaths) in China and more than 115.8 million confirmed cases worldwide (2.6 million deaths). According to Zeng et al. (2005), SARS slowed down the growth rate of China and reduced tourism income by US$16.9 billion with passenger transportation declining by 23.9%, and aviation passenger traffic by nearly 50%. According to Wishnick (2010) Asian states lost US$12–18 billion as the SARS crisis depressed travel, tourism, and retail sales. Nevertheless, after the SARS crisis, tourism recovered rapidly (Zeng et al., 2005) and international passenger traffic recovered within nine months (IATA Economics, 2020a).

Despite the strong warning messages from the WHO due to the high mortality rate (64%) of H5N1, traffic was not impacted at all in the case of the Avian influenza outbreak of 2005, possibly because of the low inter-human transmissibility of the disease (Chung, 2015). IATA (2009) reported that passenger demand fell by 11.1%, capacity dropped by 4.4% and load factor reduced by 5.4% compared to March 2008. The timing of swine flu overlaps with the global economic crisis and makes it difficult to accurately measure any impacts of H1N1 on travel demand and supply, especially when there were no travel restrictions imposed. IATA Economics, 2020a, IATA Economics, 2020b reports that the 2005 and 2013 avian flu outbreaks had mild and short-lived impacts and the traffic rebounded very quickly.

2.3. COVID-19

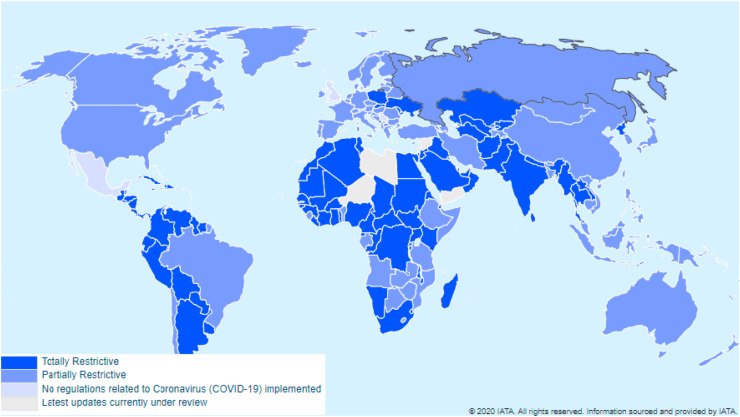

COVID-19 was initially recorded as an unidentified coronavirus in Wuhan, China at the end of December 2019 and was classified as the COVID-19 pandemic on March 11, 2020 by the World Health Organisation (WHO). The Chinese market has noticed very strong growth the recent years with an additional 450 million passengers per year flying to/from and within China compared with a decade ago (IATA Economics, 2020a). The COVID-19 outbreak coincided with the busiest travel season for China, i.e. the Chinese New Year. Frequencies of flights and high-speed rail services out of Wuhan related to the number of COVID-19 cases in the destinations (Zhang et al., 2020b). Therefore, a number of travel restrictions were imposed on Chinese travellers leading to the collapsing of traffic. China was the first to experience the pandemic and has now entered a ‘restart phase’. COVID-19 is an unprecedented situation having significant impact on flight volumes for a prolonged period (Dube et al., 2021). According to UNWTO (2020) in May 2020 from 217 destinations worldwide, 97 (45%) of them partially or completely closed their borders to tourists, 65 destinations (30%) suspended international flights partially or completely and 39 destinations (18%) banned the entry for passengers from specific countries of origin or passengers who have transited through specific destinations (Fig. 2 ). When the COVID-19 situation escalated, further travel restrictions were imposed (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 2.

Type of travel restriction by destination with COVID-19 travel restrictions in May (Source: IATA, May 31, 2020).

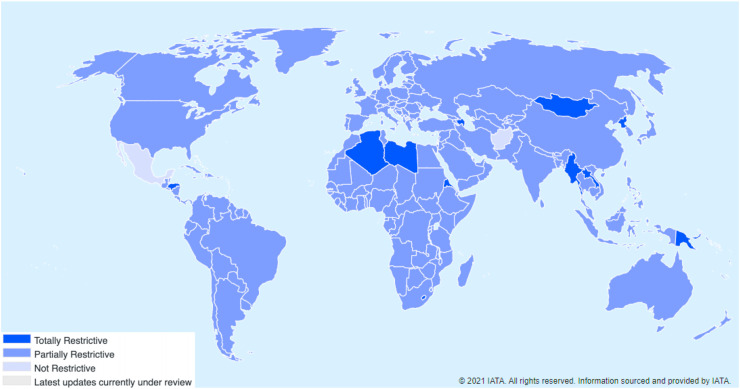

Fig. 3.

Type of travel restriction by destination with COVID-19 travel restrictions in March (Source: IATA, March 05, 2021).

Iacus et al. (2020) used trends analysis to reflect the impact of reduced traffic demand and lockdowns in Europe and found that international flights decreased significantly. They also highlighted that different lockdown strategies impact aviation in different ways. Budd et al. (2020) found that the pandemic resulted in a contraction of fleet size, labour and network coverage. Carriers reported 50% no-shows for flights and reduced future bookings (IATA, 2020a, IATA, 2020b, IATA, 2020ac, IATA, 2020bc). The industry urged regulators to revise exiting rules and regulations and show flexibility. According to Sun et al. (2020), the global airport network remained unchanged for the first 2–3 months. This can be explained by the slot regulation in congested airports. With 43% of global passenger traffic departing from over 200 slot coordinated airports (IATA, 2020b), airlines initially flew ghost flights to comply with slot rules. These rules were relaxed initially for operations to China and Hong Kong, and after industry requests, the EC revised the EU Airport Slots Regulation (EEC 95/93). Consequently, capacity fell even further. The aviation fee reductions and cost support that many countries, including China, offer, contributes to the reduction of airlines' marginal costs, but are not sufficient to make the carriers profitable according to Czerny et al. (2020).

Airport Council International (ACI, December 2020) expects a US$118.8 billion reduction of airports’ revenue for 2020, a reduction of 65% compared to the pre-COVID-19 prediction of US$171.9 billion, while Asia/Pacific airports loss of gross revenues is estimated to US$29.6 billion together with a 59.2% decrease in passenger numbers, compared to the business-as-usual scenario (ICAO, February 2021). European airports lost US$40.8 billion of revenue and 1.72 billion passengers in 2020 compared to the previous year, a decrease of −70.4% in passenger numbers, according to ACI Europe (February 2021). ICAO (February 2021) estimates US$371 billion loss of gross passenger operating revenues of airlines, a reduction of 50% of seats offered and a reduction of 2699 million passengers (−60%) in 2020 compared to 2019 levels. From International passengers traffic, airlines have lost US$250 billion of gross operating revenues from international passenger traffic drop (−74%) and US$120 billion of gross operating revenues from domestic passenger traffic drop (−50%). Table 1 summarises the estimated impact per region. Table 2 focuses on the Asia and Pacific region.

Table 1.

Estimated impact on passenger traffic by region for 2020 (Source: ICAO, February 2021).

| Capacity | Passengers (million) | Revenue (US$billions) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | −58% | −769 | −100 |

| Asia and Pacific | −45% | −921 | −120 |

| North America | −43% | −599 | −88 |

| Middle East | −60% | −132 | −22 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | −53% | −199 | −26 |

| Africa | −58% | −78 | −14 |

Table 2.

Overview of Asia and Pacific region (Source: IATA Economics, January 2021).

| 2019 | Sep-20 | Oct-20 | Nov-20 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia Pacific | ASK | 4.4 | −57.2 | −54.4 | −52.9 |

| PLF | 81.9 | 69.3 | 69.0 | 66.4 | |

| Asia- Europe | RPK | 6.7 | −92.9 | −92.9 | −93.2 |

| Within Asia | RPK | 5.3 | −98.2 | −98.2 | −97.7 |

| Asia -Europe | Yields | −7.7 | -.32 | 6.1 | −1.6 |

| Within Asia | Yields | −4.5 | −4.4 | −6.4 | −9.9 |

Notes: ASK/RPK/Yields: % change on a year ago; PLF: % of ASK.

As a general rule of thumb, it is advisable for airlines to have cash liquidity equivalent to at least 20–25% (i.e. 2-3 months) of annual revenues. This is seldom the case; however, with the global average liquidity for airlines worldwide being two months (IATA, 2020c) a number of airlines are in financial problems. Major airlines as well as tour operators have already requested tens of billions of US$ in state aid (Gössling et al., 2020). Small and medium sized airlines are even more vulnerable to the crisis with many appointing interim examiners (e.g. CityJet), seeking government support (e.g. Loganair) and even collapsing (e.g. Compass airlines).

Government support to the aviation sector is in the form of government-backed commercial loans and government guarantees, recapitalisation through state equity, flight subsidies, nationalisation, deferral and/or waiver of taxes and charges, grants and private equity (Abate et al., 2020). For example, in 2020, Air France-KLM Group (France) received US$8.5 billion, Lufthansa US$8.3 billion, Ryanair US$812.3 million, Aegean airlines US$145.5 million. The US suspended certain aviation related taxes under the CARES act. As discussed below, China has taken a number of measures (e.g. reduced airport charges and air navigation charges, triple Stimulus vouchers in Chinese Taipei). Ex-President Donald Trump signed a stimulus bill in the US that provided a US$58 billion bailout to the airline industry with US$29 billion in payroll grants for workers and US$29 billion in loans for the airlines. EUROCONTROL postponed more than EUR 1 billion in air navigation fees. IATA (2020c) reports that government aid made available to airlines due to COVID-19 exceeds US$173 billion.

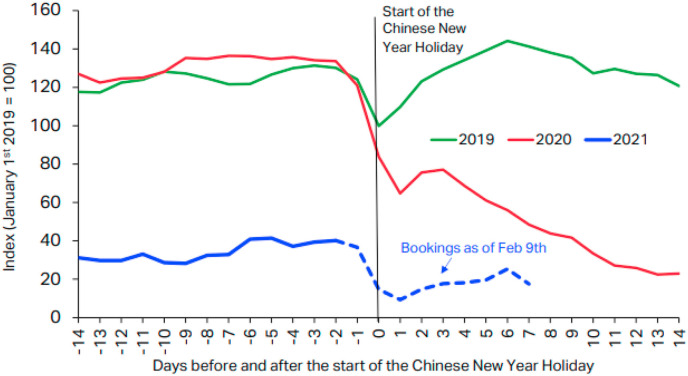

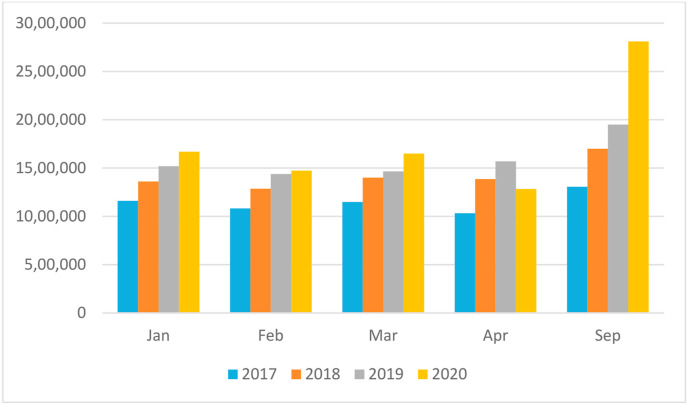

Hall et al. (2020) recorded the system dimensions of tourism in COVID-19 affected destinations and argue that the extent to which transit regions, such as major aviation hubs, are open to tourists is extremely important for access to a destination. This can affect the traffic flows between destinations. Connecting cities by air is critical for recovering, as rapid air transport supports the supply chain and facilitates inbound tourism, an important driver for emerging economies. Sun et al. (2020) highlighted that the impact of COVID-19 on international flights have been stronger than on domestic and it has affected the network significantly. International traffic cannot be restored based the on actions and decisions from individual countries when other markets remain closed. Hall et al. (2020) state that international travel is more complicated to restart in comparison to domestic. Sun et al. (2020) in their analysis of 213 counties proved that connectivity patterns are heterogeneous and depend on the number of cases in the various countries. International travel recovery will depend on vaccine development and deployment, traveller anxieties and consumer confidence, the vulnerability of certain market segments (e.g. senior travellers), but also the extent of financial adversity. As discussed below, China has already shown significant signs of recovery, according to Sun et al. (2020) and the domestic market is near full recovery. Yet, the air travel revenue boost from Chinese New Year is absent. In February 2019, domestic passenger revenues (excluding ancillaries and taxes) were 9% of the total annual revenues, i.e. US$5.8bn (IATA economics, February 2021). On February 9th, bookings were down by an amount equivalent to a 19% fall in global bookings and passenger volumes in China market (domestic + international) were around 69% lower compared to where they would be expected to be at a similar stage (i.e. just before the start of the holiday) (Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

Daily China domestic and international Passenger Traffic (source: IATA economics, February 2021).

3. Data

The airline analysis here is both demand and supply orientated, evaluating the Chinese domestic market, but also the China to Europe and China to other Asian destinations. The supply analysis was conducted using Official Airline Guide (OAG) data. OAG is a comprehensive subscription database that records 96% of global passenger itineraries. OAG has been used in various academic papers (e.g. Corbet et al., 2019; Lei and O'Connell, 2011; Pagliari and Graham, 2019). This database does not include charter flights and in this analysis, cargo flights are not included. Daily supply data reported by origin-destination (O-D) pairs from January 2017 to December 2020 was collected.

The demand analysis was conducted using Sabre AirVision Market Intelligence Data Tapes (MIDT) subscription database. MIDT collects data on passenger demand, fares and airline revenues, but includes only indirect bookings such as online travel agents and global travel retailers through a Global Distribution System (GDS). The provided data uses an algorithm that takes direct bookings into account to estimate the total demand, fares and revenues. Suau-Sanchez et al. (2016) suggest that 55% of all bookings for network airlines are done through GDSs, while Low-Cost Carriers (LCCs), that prefer direct sales, only get 16% of their bookings via GDSs. This is a database used extensively by scholars (Bock et al., 2020; Suau-Sanchez et al., 2016; O'Connell et al., 2020). There were limitations for some data, which was unavailable for the latest months of November and December 2020; thus November and December 2020 travel demand information could not be included in the later parts of the analysis.

For the airport analysis, the OAG data for the domestic, Asian, European and North American markets was used to track overall trends at the airports before and after COVID-19. Whilst this does not capture all activity at the airports, it includes all the main markets and so was considered a fair representation of the situation.

4. Impact analysis results

4.1. The overall picture

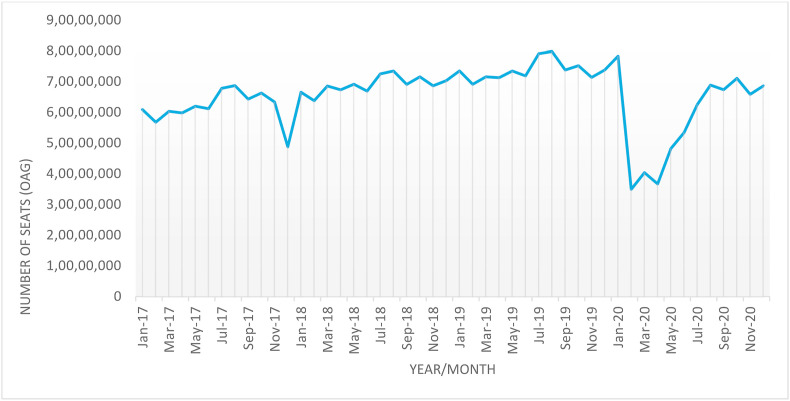

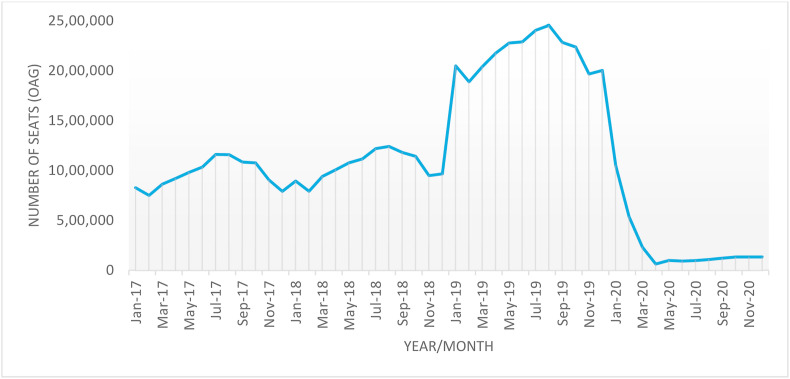

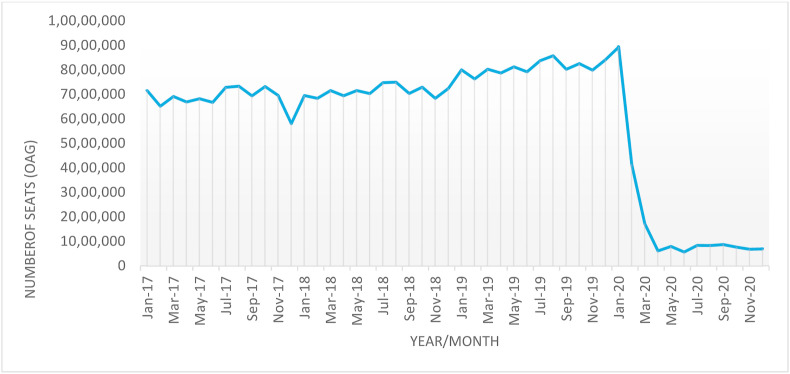

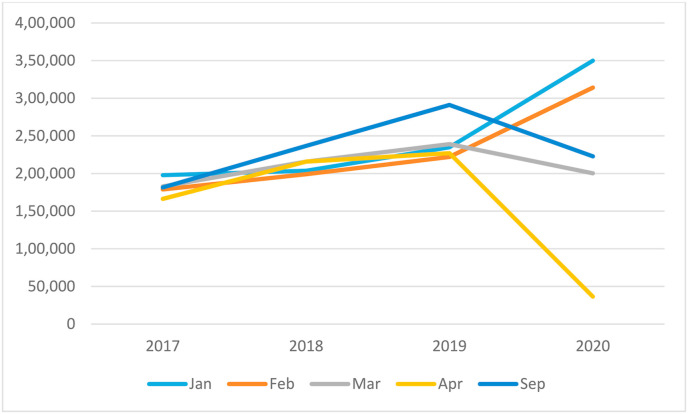

The overall picure in China in terms of air carrier seat capacity, passenger traffic and passenger revenues has been mixed depending on the market, though in all cases there has been prolongued negative growth during 2020 in comparison with previous years. Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7 show how seat capacity has developed over a 48 month time-series from January 2017 to December 2020 on China Domestic, China to Europe and China to rest of Asia markets respectively. The observed drops in capacity might have been even worse if the Chinese government had not introduced a payment scheme of US$0.0027 per ASK for flights on routes served by multiple airlines, and US$0.0081 per ASK for a route where the carrier was a sole operator to encourage the airlines to keep flying (Flightglobal, 2020). The sustained presence of the virus along with government imposed travel restrictions, as shown, for example, on China to Europe markets (Fig. 6) by the sudden drop in capacity in February 2020 and the absence of any recovery ever since on, made the opening up of international markets particularly difficult. Only the Chinese domestic market saw any pronounced rebound in capacity. Europe and rest of Asia markets continued to languish at 7% and 8% of 2019 capacity levels respectively by December 2020 (Fig. 7).

Fig. 5.

China Domestic time-series seats Jan 2017–Dec 2020.

Fig. 6.

China to Europe time-series seats Jan 2017–Dec 2020.

Fig. 7.

China to the rest of Asia time-series seats Jan 2017–Dec 2020.

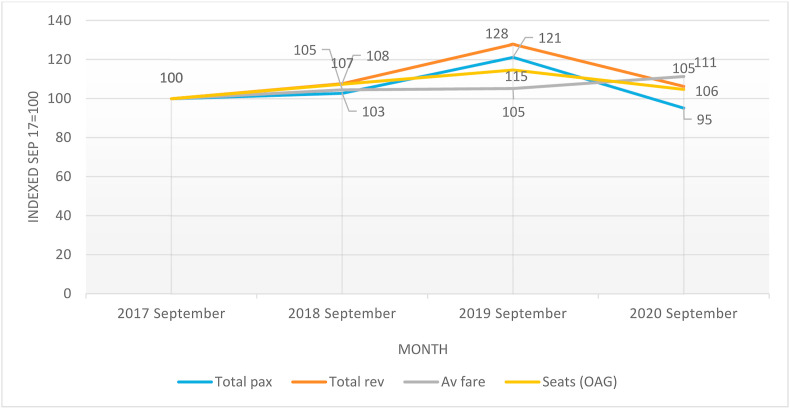

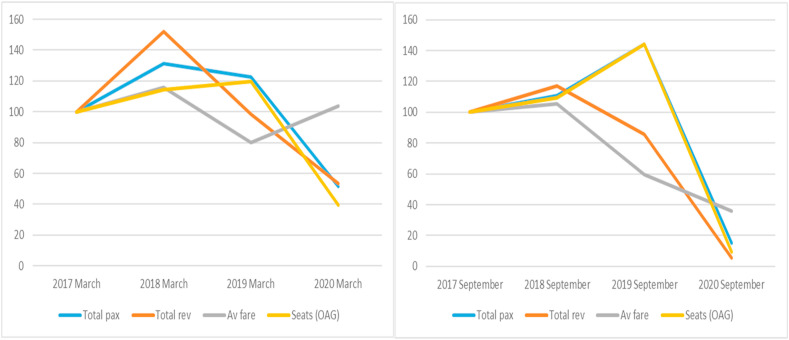

Aside from the normal seasonal variation, which can be seen on the more leisure intensive China to Europe markets in comparison to the China Domestic and China to rest of Asia markets, year-on-year increases in capacity up to the end of 2019 can be observed, followed by significant capacity drops as lockdown measures and travel restrictions took hold first in China in January 2020, and then by other countries from February 2020 onwards. As early as April 2020, China Domestic capacity had partially rebounded with levels being as much as 63% of those observed in April 2019. By December 2020, domestic seat capacity had recovered to 93% of 2019 levels. A similar pattern can be observed in Fig. 8, Fig. 9, Fig. 10 for passenger traffic and passenger revenues on all three observed China traffic markets (Domestic, Europe and rest of Asia). In all cases by September 2020, passenger traffic and passenger revenues were smaller than September of the previous year and with the exception of the domestic China market (revenues and seats only), smaller than September 2017 levels as well.

Fig. 8.

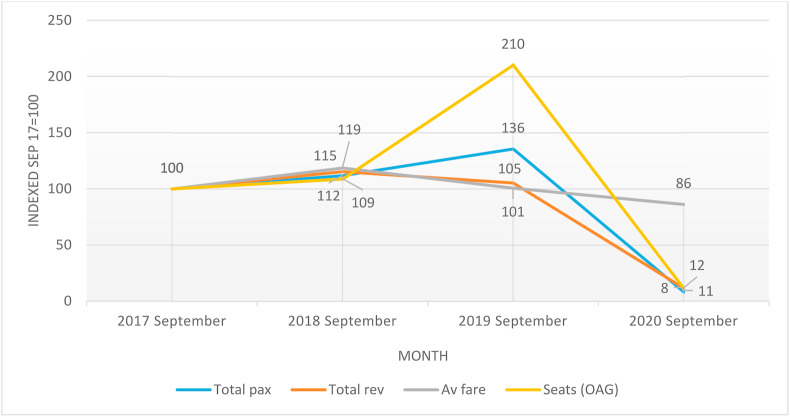

China Domestic September vs September comparison 2017–2020.

Fig. 9.

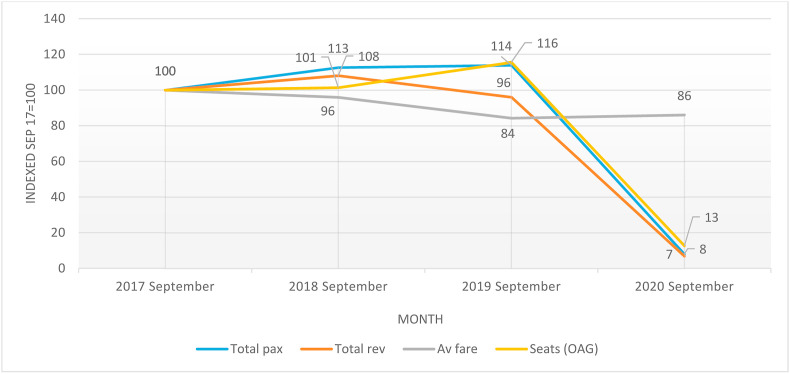

China to Europe September vs September comparison 2017–2020.

Fig. 10.

China to the rest of Asia September vs September comparison 2017–2020.

There is some variation between markets that is worthy of note. China to Europe passenger revenues were already on a downward trend in 2019 before the virus hit, primarily linked to downward pressure on average fares on what were becoming increasingly competitive, lower yield markets. This was driven by large capacity increases by Chinese based carriers into European markets with Air China, China Eastern, China Southern and Hainan Airlines all seeing double digit growth in 2018 versus 2017, for example (Anna.aero, 2019). Responding to a slowing rate of GDP growth in China,1 airlines on these markets had to reduce fares in order to preserve the same number of passengers as shown particularly in Fig. 10. The Chinese domestic market (Fig. 8) saw year-on-year increases both in passengers revenues and passenger traffic despite small average fare increases through to September 2019, which is indicative of the more inelastic, expanding domestic market within China and the more controlled competitive environment in which air carriers operate. Remarkably, by September 2020, passenger traffic and revenues had rebounded and were only marginally below September 2019 levels, and the same or greater than September 2018 and 2017 levels.

China to rest of Asia passenger revenues were increasing year-on-year (Sep 19 vs Sep 18 vs Sep 17) at a time when average fares saw reductions (Fig. 8), indicative of a more elastic market than China domestic. By September 2020, China to Europe and China to rest of Asia passenger traffic and revenues were in free fall. In September 2020 average fares were reduced to 85% of September 2019 levels on China to Europe, reflecting carrier attempts to entice passengers back into markets in between the lifting and re-imposition of travel restrictions. On domestic China, average fares actually increased by 6% on September 2019 levels reflecting Chinese carrier ability to start charging premiums for extra space. China to rest of Asia average fares in Sep 2020 remained relatively stable from the previous years, given the previous downward pressure on fares already observed in this market, providing carriers with very little wiggle room to decrease fares even further to try and entice passengers back. The more rigid continuation of intra-Asia travel restrictions would have also prevented any appetite for carrier market testing through reduced fares.

To statistically test the difference in market developments between China domestic and China to Europe and rest of Asia routes, a one-tail t-test was performed on March and September 2020 traffic, capacity and revenue changes in comparison to March and September 2019. As shown in Table 3 , the t-statistic was 2.58, which is greater than the critical value of 2.01 needed to be statistically significant. Therefore the mean differentials (Mar and Sep 2020 vs 2019) of China Domestic versus China International (China - ROA/Europe and HKG) are statistically significant and is indicative of a more marked and sustained recovery for China Domestic routes.

Table 3.

Statistical t-test (one-tail) to determine significance of recovery rate differentials between china domestic and china international markets.

| Air transport market | N | Mean | SD | Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| China rest of Asia & HK/China Europe | 6 | −77.1 | 6.65528 | 44.368 |

| China Domestic | 6 | −44.3 | 26.42852 | 697.8217 |

| Pearson Correlation | −0.65 | |||

| t Stat | 2.58 | |||

| P(T ≤ t) one-tail | 0.025 | |||

| t Critical one-tail | 2.01 |

Note: Covers top 10 China domestic routes (excluding HK), China to rest of Asia (including HK) and China to Europe routes (30 routes in total).

4.2. China domestic route, airline level analysis and premium/economy revenue comparison

In breaking down the overall Chinese domestic market into individual routes and players, it is possible to obtain some indications of which market elements have been worst and least affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

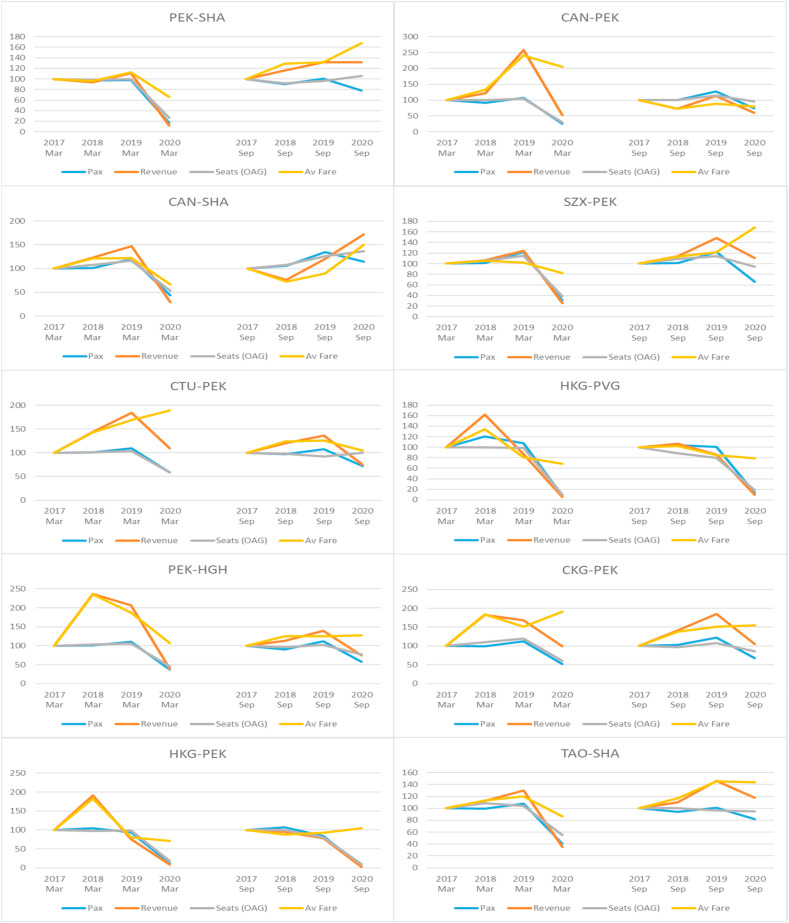

The Chinese domestic market is quite dispersed given that the top 10 routes (inclusive of Hong Kong and Macao SARs) represent around 7% of the total 373 mn Chinese domestic seats available in 2019 (See Appendix A). Despite year-on-year growth in the overall supply (as shown in Fig. 5), all of the top 10 routes as outlined in Fig. 11 witnessed downturns in traffic, capacity and revenues from the beginning of 2020 onwards. By March 2020 the worst affected routes appear to be those involving Hong Kong (HKG) and to a lesser extent those involving Beijing (PEK). The traffic losses at these two airports overall was particularly severe (see section 4.5 for more detail). The HKG-PEK route, which was the 9th busiest route in 2019 (by capacity), appears to have been the worst affected with seats, passenger traffic and passenger revenues on the route being a mere 13%, 12% and 8% of 2017 levels in March 2020. In contrast, the least affected route appears to be CTU-PEK, the 5th busiest route in 2019 with market indicators partially rebounding in March 2020 from lows in the previous month. Capacity, passenger traffic and passenger revenues were back up to 48%, 58% and 110% of March 2017 levels respectively. By September 2020, market indicators on Hong Kong (HKG) routes had deteriorated even further with −96.5% year-on-year reductions in revenue on the HKG-PEK route for example, versus −89% in March (YoY). On the Hong Kong (HKG) to Shanghai Pudong (PVG) route, year-on-year traffic picked up only sightly in September 2020 versus March with revenues only 12% of September 2019 levels (up from 6% in March 2020 YoY). Conversely, market indicators on top 10 routes involving Beijing (PEK) appeared to have partially recovered by September 2020 with the biggest recovery being observed on the Beijing (PEK) to Shanghai Honqiao (SHA) route. Despite passenger traffic recovering to 78% of 2019 levels in September (from a base of 18% of 2019 levels in March), total revenues on the route were miraculously 1% higher than September 2019 levels, boyed by higher average fares ($220 in September 2020 versus $172 in September of the previous year).

Fig. 11.

Variation in Direct seats, Passengers, Average Fares and Revenues on top 10 China domestic routes (Index 2017 = 100).

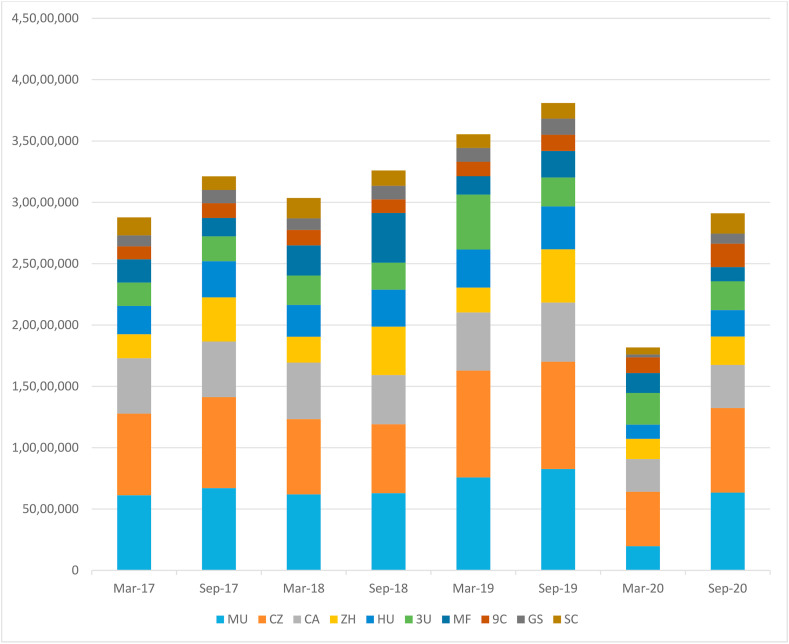

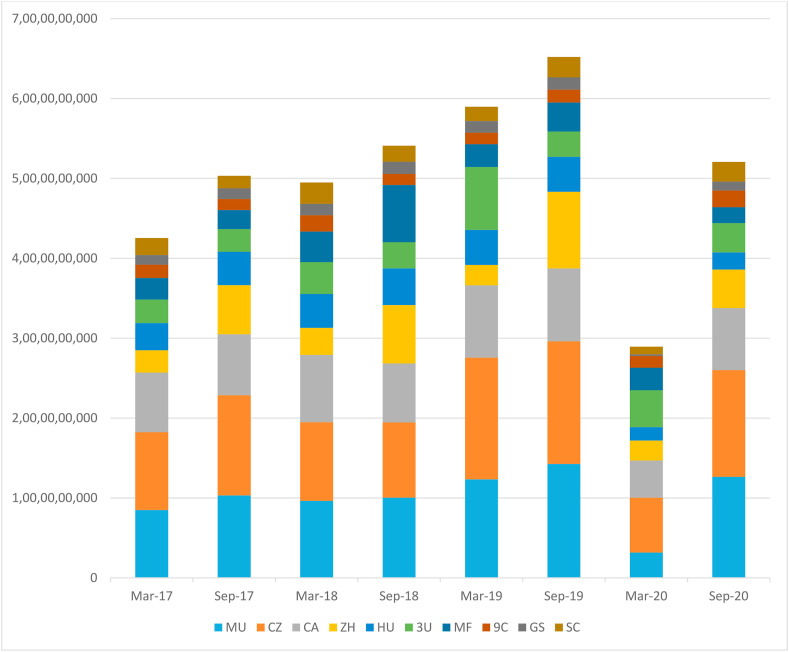

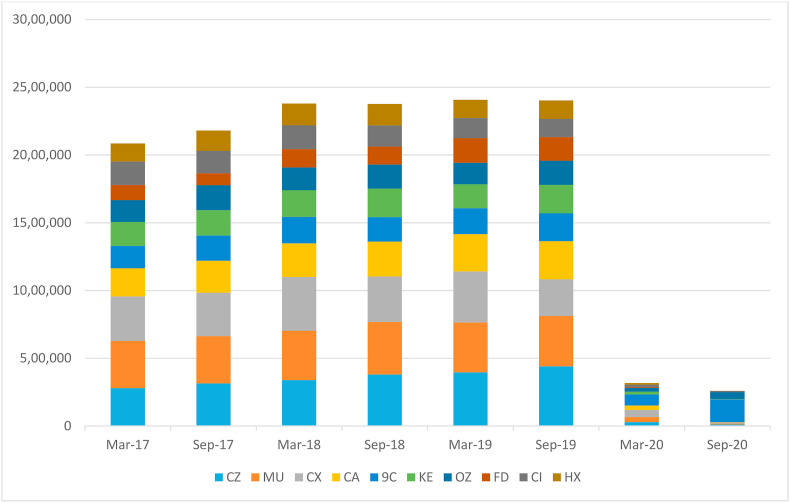

The Chinese domestic market is still dominated by the Chinese big three carriers of China Southern, China Eastern and Air China, though gains have also been made by Shenzhen and Hainan Airlines. (Appendix B). Fig. 12, Fig. 13 show variation in passenger traffic and revenues for the top 10 Chinese domestic market carriers and also the effect that individual airline variation has had on the total variation between the years 2017–2020. As expected, there have been significant drops in 2020 versus 2019 levels to the tune of around 50% in March and 24% in September. Carriers such as China Eastern (MU), Hainan Airlines (HU) and TianJin Airlines (GS) have been particularly hard hit with March 2020 traffic and revenues dropping by more than 50% whereas carriers such as Shenzhen Airlines (ZH), Sichuan Airlines (3U) and Spring Airlines (9C) have been rather less affected with traffic and revenues dropping by less than 50%. In fact in the case of low-cost carrier Spring Airlines, the impact has been negligible with passengers and revenues actually increasing marginally in March 2020 versus March 2019 and improving further by September 2020 ($209mn in total China domestic revenues up from $161mn in 2019).

Fig. 12.

China Domestic markets top 10 airlines O&D passengers March and September 2017–2020 (representing 72% of market).

Fig. 13.

China Domestic markets top 10 airlines revenues March and September 2017–2020 (representing 72% of market).

Fig. 14 illustrates the variation in seat capacity for Spring Airlines for the period January, February, March, April and September 2017–2020. Keen to employ its 12 newly acquired and more efficient A320neo aircraft in 2019 (Allen, 2020), the LCC continued to increase its seat capacity year-on-year with the COVID-19 crisis only temporarily triggering a capacity reduction response between March and April 2020 by 300,000. That said passenger load factors on Spring Airlines domestic services rebounded to 70% in April (Kawase, 2020) and its more nimble business model allowed it to take advantage of retractions amongst some of the more established players (e.g. Air China). This was in stark contrast to its international traffic, which dipped 97% (excluding HK, Macao and Taiwan) in March 2020, though as seen in (section 4.4), by September 2020 Spring Airlines managed to buck the trend on China to rest of Asia markets also with passenger traffic reducing by only 17% on September 2019 levels versus an average across the other top 10 airlines in the market of −95%. Clearly, for those airlines such as Spring Airlines with a strong and increasing presence in domestic markets combined with the offering of competitive fares, it has been possible to divert resources from international markets. With an average fare of $109 during September 2019 on Chinese domestic markets, Spring Airlines was more competitively priced than all of the major players in the market with the exception of Hainan Airlines ($99 average in Sep 2020).

Fig. 14.

Spring Airlines (9C) China domestic seat development Jan, Feb, Mar and Sep (2017–2020).

Though not as prevalent as on international markets, premium class still plays a role in Chinese domestic markets. From a base of 6% in March 2018, premium revenues as a percentage of total domestic market revenues increased to 12% in March 2019 and further to 16% by March 2020. It is possible that passengers who can afford business class travel may start to seek extra space and separation from other passengers during flight as a way of minimising the risk of contracting COVID-19 during flight.

Despite overall revenue decreases, it can be seen from Table 4 that economy class reductions versus 2019 revenues have generally been greater for the top five airlines in the market than business class reductions (−50% v −45% respectively). In the case of one carrier, Air China (CA), September 2020 premium revenues were actually 18% higher than in the same month in 2019. The picture is not consistent, however, with China Southern (CZ) and Hainan Airlines (HU) seeing greater premium reductions versus economy class reductions. According to Kawase (2020), it is possible for the reduced number of people travelling during the pandemic to avoid the cost of a business class ticket whilst still retaining the benefit of extra space in economy class due to lower load factors, especially where the value added benefits of premium class amongst some carriers are perhaps not quite as clear. As expected, on the Chinese domestic market, revenue recovery by September was quite robust in both classes with the exception of Hainan and Shenzhen Airlines.

Table 4.

% Drop in economy and business class revenues February, March and September 2020 v 2019.

| irline | Month | Economy % change | Premium % change |

|---|---|---|---|

| China Southern | Feb | −59 | −50 |

| Mar | −53 | −69 | |

| Sep | −8 | −38 | |

| China Eastern | Feb | −68 | −61 |

| Mar | −78 | −41 | |

| Sep | −12 | −1 | |

| Air China | Feb | −65 | −67 |

| Mar | −50 | −43 | |

| Sep | −21 | 18 | |

| Shenzhen Airlines | Feb | −57 | −32 |

| Mar | −45 | −1 | |

| Sep | −46 | −76 | |

| Hainan Airlines | Feb | −73 | −78 |

| Mar | −60 | −70 | |

| Sep | −48 | −64 | |

| Average % change (top 5) | −50 | −45 |

4.3. China to Europe route, airline level analysis and premium/economy revenue comparison

China to Europe is a more condensed and focussed network in comparison with the Chinese domestic market. The top 10 routes sorted by 2019 seat capacity represent 59% of all China to Europe seats in that year (Appendix A). HKG-LHR is by far the densent route followed by the Beijing and Shanghai to Moscow routes and then Beijing to other major European points including Frankfurt, Paris, Amsterdam and Munich. In part, due to the Far East network strategy focus of Finnair, owing to Helsinki's geographical location reducing Europe to China distances, HKG-HEL also makes it into the top 10 routes with a proportion of this traffic making connections from other European/Asian points.

Unlike the situation on the Chinese domestic market, prior to the COVID-19 crisis traffic growth had remained steady rather than bullish in the China to European market. There was already some evidence of reductions in average fares and revenues on these markets up to 2019. The COVID-19 pandemic excaerbated the revenue losses significantly and led to an unprecedended downturn in traffic after remaining steady in previous years. Fig. 15 provides a detailed comparison of trends in seats, average fares, revenues and passengers on the top 10 China to Europe routes in both March and September (over the 2017–2020 period).

Fig. 15.

Variation in Direct Seats, Passengers, Average Fares and Revenues on top 10 China to Europe routes (Index 2017 = 100).

Due to the time difference in the initial spread of COVID-19, it can generally be observed that significant revenue drops in China to Europe markets did not take place until March 2020 at which point market indicators started to drop quite dramatically. The worst affected routes in March 2020 appeared to involve secondary gateways. Both PEK-MUC and HKG-MUC saw March 2020 revenue drop to as little of 2% of March 2017 levels (HKG-MUC). In the case of PEK-MUC there was still some remnance of service in March 2020, though with revenues down to as little as 9% of March 2017 levels on the back of seat capacity reductions to 32% of March 2017 levels. With already reducing infection rates in China during March 2020 and still controlled rates of infection in Russia, March 2020 saw PEK-SVO in particular being one of the least affected routes with traffic, seats and revenues all retaining between 50% and 60% of 2019 levels. Within this group of observed routes, HKG-LHR continued operations albeit at a reduced level. Interestingly, average fares spiked in March 2020 at US$1,052 up from US$923 in March 2019 and US$772 the previous month (Feb 2020). This reflects attempts by carriers on this route to try and compensate for falling load factors by charging non-discretionary, inelastic passengers higher fares, who would often consider their journeys to be essential during this period. By September 2020, the situation had actually worsened as international markets continued to bear the brunt of inconsistent government approaches to travel restrictions and COVID-19 response initiatives. With COVID-19 also having a big impact in Russia, top 10 routes like PEK-SVO that were looking a bit more resilient in March 2020 had also tapered off to negligible levels by September 2020. In the whole of September 2020, there were just 284 O&D passengers travelling on this route compared to over 13,000 in September of the previous year. Using the observed pairs, the situation by September 2020 was almost universally bleak. Only HKG-LHR had some remnants of traffic (13,000 versus 38,000 the year before), with average fares reducing to a low of US$713. Despite the mandatory quarantines that were in place in the UK at this time, the country was still partially open to international flights, including from China (and Hong Kong).

In terms of top 20 airlines serving China to Europe markets, despite not having any direct services, Emirates is a large player in this market, transporting passengers between Europe and China via its Dubai, UAE hub (Appendix B). Aside from Emirates, Air China, Aeroflot and Cathay Pacific are the largest players with some of the main European carriers such as British Airways, Lufthansa and Air France also in the top 10.

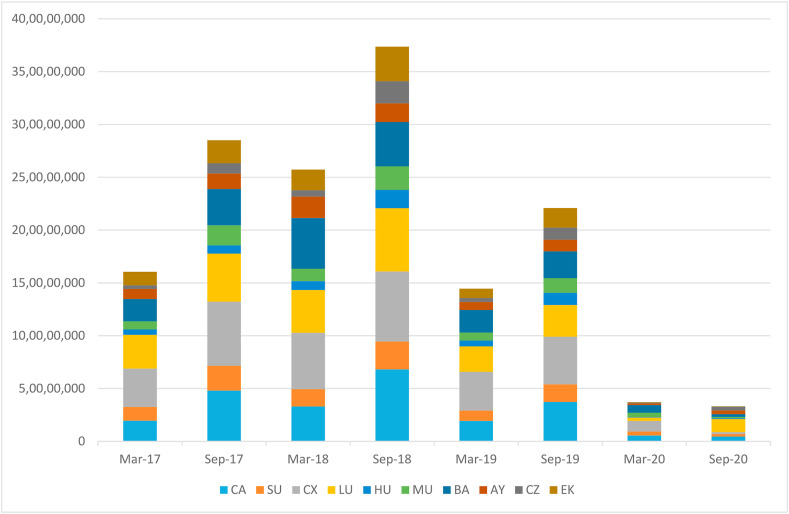

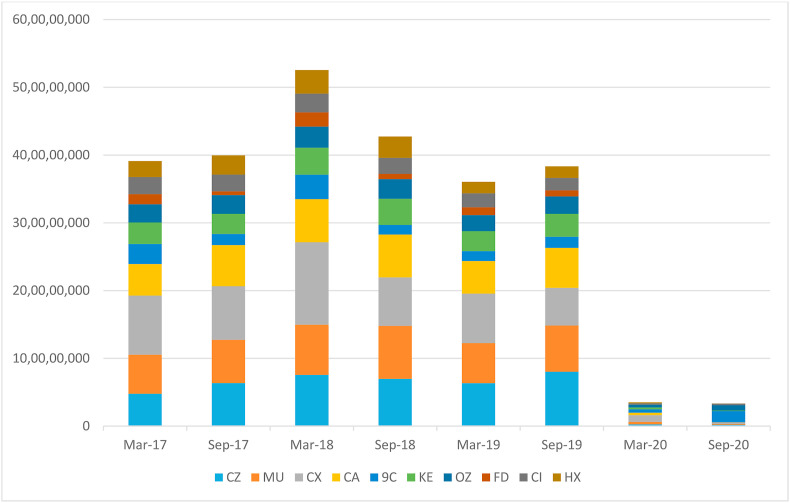

In contrast to the Chinese domestic market, in March 2020 there was as little as 29% of March 2019 traffic amongst the top 10 carriers serving the China to Europe market. By September 2020, the market situation had deteriorated further to only 10% of September 2019 levels. Within this overall picture some carriers have been more acutely impacted by the downturn and travel restrictions than others. Fig. 16, Fig. 17 show that the rate of contraction for carriers such as Hainan Airlines (HU), Finnair (AY) and Emirates (EK) has been more pronounced than it has been for Air China (CA), who managed to retain at least some traffic from areas such as Whenzou, Beijing and Shanghai mainly to points in Italy, Spain, Germany and France. For Emirates, September 2020 revenues were down to a mere 2% of September 2019 levels, whilst in March 2020 they were already down to only 5% of March 2019 revenues. For Air China at least some China to Europe revenues have been retained at 23% of 2019 levels in March 2020 reducing to 14% in September 2020.

Fig. 16.

China to Europe markets top 10 airlines O&D passengers March and September 2017–2020 (representing 69% of market).

Fig. 17.

China to Europe markets top 10 airlines revenues March and September 2017–2020 (representing 69% of market).

In March 2020, China Eastern's revenues on China-Europe markets was still as much as 55% of 2019 levels. As can be seen in Fig. 18 , China Eastern's average fares increased significantly in March 2020 versus March 2019 at the same time as passenger and seat numbers were decreasing. Given carriers such as China Eastern are 100% government owned and supported, it has been possible for China Eastern to continue running services where possible, focussing on non-discretionary travellers with a higher willingness to pay. This appeared to at least initially have the effect of partially stemming the revenue losses resulting from the downturn. By September 2020, however, China Eastern European market revenues had reduced to only a fraction of 2019 levels (8%), showing the limited number of levers air carriers have had during the pandemic in trying to stem income losses on international routes.

Fig. 18.

China Eastern (MU) average fares, direct seats, passengers and revenue trends (March and September 17 = 100).

The relative importance of premium revenues on the China to Europe market is significant in comparison to the Chinese domestic market. In March 2019 premium revenues were as much as 87% higher than economy revenues for the top five carriers in the market coming in at US$64mn. Cathay Pacific (CX) and Lufthansa (LH) in particular have been heavily reliant on premium traffic. Premium class revenue for Lufthansa in March 2019 were US$17mn whilst revenues in economy class for the same month were only US$7mn. For Cathay Pacific the difference was even greater with the carrier earning US$28mn premium revenues in March 2019 versus only US$9mn in economy class. Cathay's extra premium revenues can be partly explained by its greater premium service focus (Flannery, 2019) and therefore higher average yields on China-Europe markets than carriers like Lufthansa (CX had 23% higher average yields than Lufthansa in March 2019).

With the exception of Aeroflot in February 2020, revenue drops in February, March and September 2020 versus the previous year were invariably found to be greater in the premium classes for the top 5 carriers in the China to Europe market (Table 5 ). This combined with the higher premium class contribution to overall passenger revenues in these markets has led to a particularly severe revenue impact for carriers like Cathay Pacific, Lufthansa and to a lesser extent Air China and Emirates. Aeroflot's reliance on premium revenues is much lower. With a negligible domestic market, Cathay Pacific is particularly exposed to the more prolongued downturn period noted for international/intercontinental versus domestic routes. Though not specifically shown in this study, carriers like Lufthansa have not been quite as vulnerable from an overall market perspective as Cathay Pacific due to their ability to restart operations within domestic and regional intra-European markets during the summer 2020 period, though this tailed off again by the Autumn of 2020 due to second waves of the virus in Europe.

Table 5.

% Drop in economy and premium class (premium economy, business and first) revenues February, March and September 2020 vs 2019.

| Airline | Month | Economy % change | Premium % change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air China | Feb | −15 | −65 |

| Mar | −53 | −86 | |

| Sep | −82 | −90 | |

| Emirates | Feb | −25 | −92 |

| Mar | −88 | −99 | |

| Sep | −98 | −98 | |

| Aeroflot | Feb | −38 | 4 |

| Mar | −57 | −71 | |

| Sep | −93 | −95 | |

| Cathay Pacific | Feb | −43 | −49 |

| Mar | −59 | −77 | |

| Sep | −89 | −96 | |

| Lufthansa | Feb | −73 | −82 |

| Mar | −87 | −87 | |

| Sep | −75 | −87 | |

| Average % change (top 5) | −65 | −78 |

4.4. China to rest of Asia route, airline level analysis and premium/economy revenue comparison

As can be seen in Appendix A, Hong Kong dominates the largest routes between China and the rest of Asia. The densest route is HKG-TPE, with Hong Kong developing into the main entry point into mainland China over many years due to historical restrictions that prevented carriers from operating directly between Taiwan and mainland China. As a result of the lifting of these restrictions in late 2008, PVG-TPE has matured into a sizeable route with over 1 million one-way seats in 2019. Hong Kong remains the most popular Chinese gateway for Taiwan. China to rest of Asia markets are more concentrated than the Chinese domestic market with the top 10 routes representing around 20% of total capacity but notably less concentrated than the China to Europe market. Despite there being sizeable traffic from other major Chinese points such as Beijing (PEK) and Guangzhao (CSN) to other Asian countries, none of them made the top 10 markets due in part to the dominant position of Hong Kong as an international and intercontinental gateway hub both to the Hong Kong economy itself and also to the heavily populated Pearl River Delta conurbation in southern mainland China.

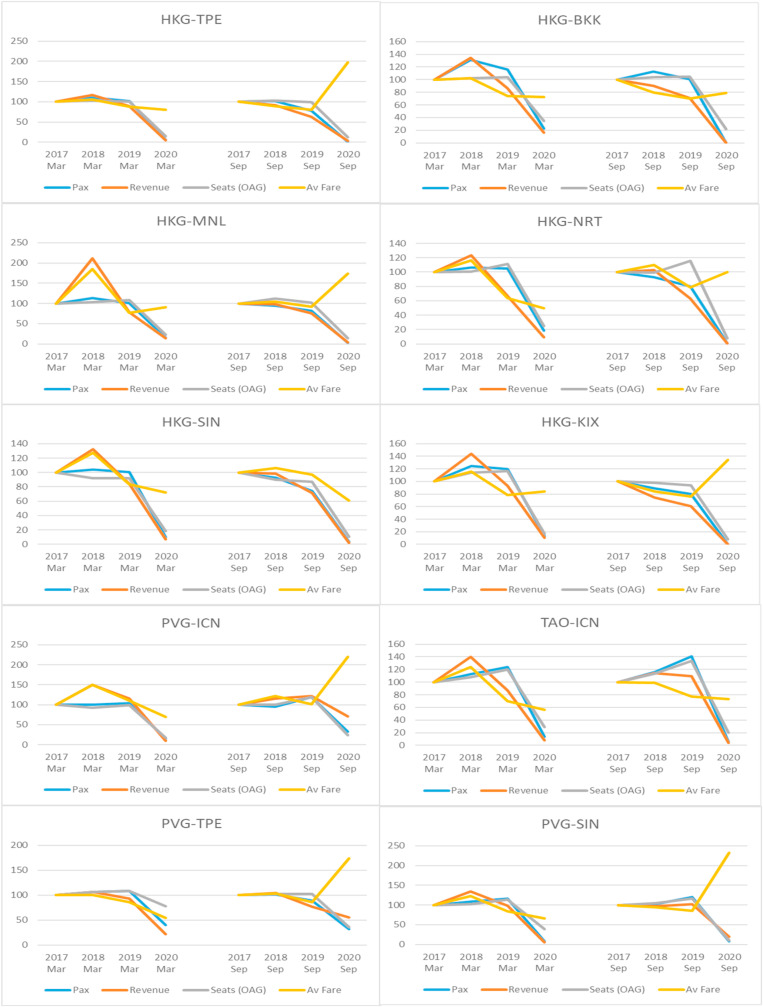

Given stricter COVID-19 controls in Hong Kong in comparison with other regions of China, routes involving Hong Kong were badly affected in both March and September 2020 versus previous years (Fig. 19 ). Seats and passenger numbers had reduced to negligible levels from Hong Kong to Tokyo (Narita), Manila, Taipei, Singapore, Osaka and Bangkok. Although performance varied quite considerably between the top 10 routes prior to the COVID-19 epidemic, the observed reduction in seats, traffic and passenger numbers has been more uniform amongst the top 10 routes, when compared to China domestic markets. The only possible exception to this was the PVG-TPE route, whereby in light of the temporary difficulty in continuing essential Taiwan-China journeys through the Hong Kong gateway, travellers who perceived journeys to be essential were able to use Shanghai Pudong with more ease than Hong Kong. Services continued to be available on PVG-TPE during this period with EVA Airways, China Airlines and Air China among others. Seats offered on PVG-TPE were as high as 70% of March 2019 levels in March 2020 though load factors achieved (around 40%) were notably lower with passengers transported being only 40% of March 2019 levels.

Fig. 19.

Variation in Direct Seats, Passengers, Average Fares and Revenues on top 10 China to rest of Asia routes (Index 2017 = 100).

The top 20 airlines operating in the China to rest of Asia represented 66% of total 2019 passenger traffic in this market (Appendix B). Due to Hong Kong's presence in Chinese inter-regional markets, Cathay Pacific broke into the Chinese big three carriers, surpassing Air China with over four million O&D passengers in 2019. Nimble low-cost carrier Spring Airlines made considerable gains on the Big 3 carriers too and was the largest low-cost carrier operator in the China to rest of Asia market in 2019. Non-Chinese carriers also have a presence in the market with Korean Air (KE), Asiana Airlines (OZ), AirAsia (AK) and Thai AirAsia (FD),2 all competing effectively in their home markets and on some of the primary routes (Appendix A).

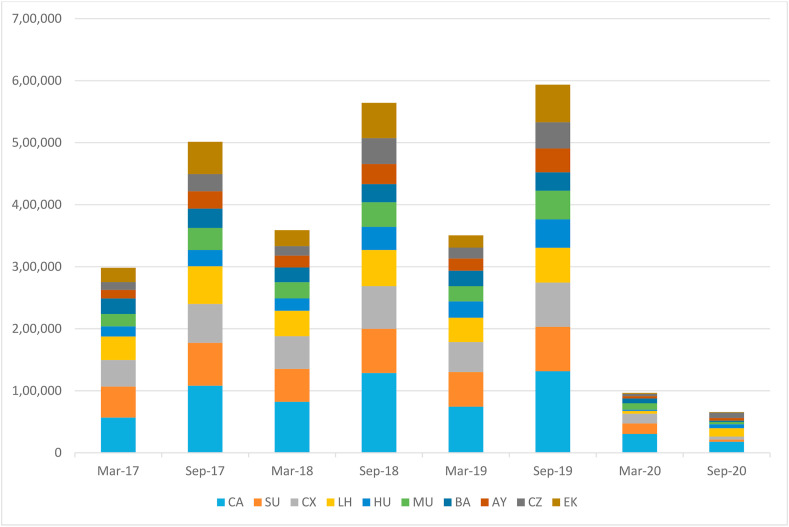

One of the more striking aspects of the China to rest of Asia market in comparison to the others is that passenger numbers and revenues fell dramatically in almost all cases and with very few exceptions in both March and September 2020 versus previous years (Fig. 20, Fig. 21 ). Within the top 20 carriers, March 2020 revenues, for example, were decimated as they represented as little as 11% of March 2019 levels (Fig. 20) in comparison to 51% for China domestic and 24% for China to Europe. This can be explained firstly by the timing of the data. March 2020 represented the height of the public health emergency and travel restrictions preventing normal economy activity from taking place. South Korea, Japan, Singapore and to a lesser extent Malaysia are all major regional air traffic markets to and from China and have been amongst the most conservative in their approaches to mitigate the risks posed by COVID-19. Secondly, in the absence of standardized approaches to public health across the region, it was not possible to create safe travel zones or travel bubbles in which people could continue to travel freely. Strict testing, contact tracing and quarantining measures coupled with temporary travel bans led to an almost temporary state of paralysis that persisted through to September 2020. Interestingly the only carrier that was impacted to a lesser extent was Spring Airlines (9C) an LCC. Keen to replicate their damage limitation strategy as observed on Chinese domestic markets, Spring Airlines attempted reduce average fares significantly. By March 2020 average fares had decreased to US$63 from highs of US$186 in March 2018. Due to the downturn in economic activity during this period and travel restrictions, Spring Airlines decreased capacity significantly in April 2020 to just over 36,000 seats (Fig. 22 ), focussing efforts and resources on domestic markets as detailed in Section 4.2. Perhaps seizing on the retrenchment of almost all other players in the market, by September 2020 Spring Airlines (9C) had returned to rest of Asia markets in a significant way, offering 223,000 seats, 77% of 2019 levels with total passengers revenues actually remaining constant in both September 2019 and 2020 at around US$16.5 million. Spring Airlines was able to operate thrice daily flights, for example, from Shanghai Pudong to Bangkok and twice daily operations to the popular resort locations of Jeju (Korea), Phuket and Chiang Mai (Thailand) with surprisingly healthy load factors averaging 75% across these routes.

Fig. 20.

China to rest of Asia markets top 10 airlines O&D passengers March and September 2017–2020 (representing 46% of market).

Fig. 21.

China to rest of Asia markets top 10 airline revenues March and September 2017–2020 (representing 46% of market).

Fig. 22.

Spring Airlines (9C) China to the rest of Asia seat capacity (OAG).

In comparison with the China to Europe market, carriers operating on China to Asia routes were not as dependent on premium traffic. That said by March 2019, premium revenues still represented around 24% of total revenues for the top 5 China to rest of Asia carriers, up from 15% the year before. There is a higher level of variation in this group of carriers, however, with Spring Airlines having a one-class product and therefore zero premium revenues, and Cathay Pacific earning around US$20 million in business class revenues on routes to other Asian countries in January 2020 or 30% of total revenues in these markets.

In almost all cases and across both classes, revenue drops are observed to have been more severe on the China to rest of Asia market versus China Domestic and even China to Europe with the notable exception of Spring Airlines in economy class during September 2020 especially. Premium revenues have generally dropped at similar rates to economy class revenues, suggesting that load factors were low enough for passengers travelling to consider that they would generally have ample space in economy class anyway (Table 6 ). In the medium-term it may be necessary for carriers to reassess aircraft class configurations on regional markets and monitor bookings closely to see if business class would rebound as quickly as economy class, especially on shorter duration sectors. By September 2020 there was no evidence of any significant differences between classes, however. The advantages of having more space and distance between passengers in business class may well be outweighed by reductions in budgets or the perceived need for as much business travel as before. Moreover, there are lower levels of disposable income more generally amongst travellers as Asian economies enter into a period of slowing growth or in the case of some emerging economies a yet to be determined period of recession – for example Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam given their increased reliance on international tourism (Gunia, 2020).

Table 6.

% Drop in economy and premium class revenues February, March and September 2020 vs 2019.

| Airline | Month | Economy % change | Premium % change |

|---|---|---|---|

| China Southern | Feb | −82 | −91 |

| Mar | −96 | −96 | |

| Sep | −98 | −95 | |

| China Eastern | Feb | −80 | −83 |

| Mar | −94 | −95 | |

| Sep | −98 | −97 | |

| Cathay Pacific | Feb | −80 | −76 |

| Mar | −85 | −90 | |

| Sep | −99 | −97 | |

| Air China Limited | Feb | −80 | −81 |

| Mar | −92 | −96 | |

| Sep | −100 | −99 | |

| Spring Airlines | Feb | −48 | N/A |

| Mar | −65 | N/A | |

| Sep | 2 | N/A | |

| Average % change (top 5) | −80 | −91 |

4.5. Impact on airports in China

In 2019, there were 239 civil airports with scheduled flights in mainland China (excluding Hong Kong and Macau) handling over 1.3 billion passengers and 11.6 million aircraft movements. Fifteen million passengers were on international flights, making up around a fifth of all passengers (if the double counting associated with domestic passengers is excluded). Thirty-nine airports handled over 10 million passengers, a further 35 handled 2–10 million passengers, and there were 165 with less than two million passengers each (Civil Aviation Authority of China – CAAC. 2020a).

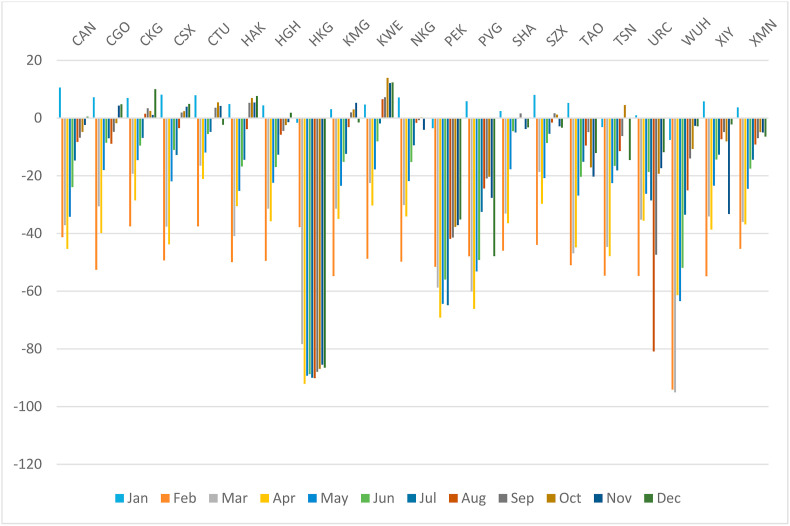

Fig. 23 shows the total traffic development (for the key European, North American, Asian and domestic markets) in terms of aircraft outbound frequencies (assuming inbound frequencies show similar trends) for the largest 20 mainland airports (by passenger numbers in 2019) plus Hong Kong airport for 2020 compared to 2019. All individual airport frequencies were down by at least 40% in February 2020 compared to February 2019 with the exception of Wuhan - the epicentre of the coronavirus outbreak - where there was a fall of around 95% with only aid and rescue flights being operated, and at Chengdu and Chongqing airports where the decline was slightly less than 40%.

Fig. 23.

% Change in outbound frequences at the largest 21 Chinese airports (including Hong Kong) January–December 2020 vs 2019.

Most airports, with the exception of Beijing Capital, Shanghai Pudong, Wuhan and Hong Kong experienced a smaller drop in traffic in March compared to February (2020 vs 2019), once certain lockdown restrictions were eased at the end of February as the infection rate dropped. This was particularly due to passengers booking flights to return home or for work. However, the rebound did not last long for most airports (with the exception of Haikou, Qingdao and Wuhan) as they then experienced a greater reduction (albeit of varying size) in frequencies in April (2020 vs 2019) compared to March. Much of this was due to continuing decreases in international flights but with some stabilisation of domestic services. From May onwards at most airports the reduction in frequencies progressively decreased and at a few airports (primarily those dominated by domestic traffic), actual monthly increases in frequency were experienced by the end of the year. Again, the notable exceptions were Beijing Capital, Shanghai Pudong and Hong Kong, where frequencies in December remained well below those offered in 2019.

This dramatic traffic loss at airports in the early months of 2020 was in spite of various measures to provide relief to the airlines, by reducing costs and promoting growth. As well as the payment support for each route (discussed above), Class 1 airports (with passenger numbers > 4% of total passengers) and Class 2 airports (with passengers between 1% and 4% of total) had their landing charges cut by 10% and parking fees waived, and there were reductions in air traffic control fees and fuel costs as well (Flightglobal, 2020). Moreover, the government waived mandated contributions from passengers and airlines to the Civil Aviation Development Fund.

By late March, China had successfully controlled the spread of COVID-19 within its borders as a result of strict lockdown and quarantine measures. However, as the pandemic spread quickly to other parts of the world, the government policy priorities of supporting and promoting air services, shifted rapidly to controlling international air services. In that month, the so-called ‘Five One’ rule was introduced, that limited one airline to serving one country from one Chinese city to one foreign city with no more than one flight a week – hence strongly influencing the range of services that could be provided from each airport (CAPA, 2020b). Then in June 2020 additional rules were introduced on international services, allowing for airlines to increase one more flight per week if no passengers on the specific route had tested positive, but if any passengers did test positive, the flights had to be suspended for a certain period of time depending on the number of positive cases. Czerny et al. (2020, 4) argue that this outcome-based regulation is a major way in which the government tried to ‘deal with the conflicting needs for improving international connectivity for economic/social reasons and for tightly controlling the spread of COVID-19 cases’. At the same time, there were travel bans/restrictions, stringent health checks and mandatory quarantine to limit the infection rates of the virus. From the end of March 2020, China closed its borders to most foreigners, and whilst these rules have been somewhat relaxed, all travellers are still required to obtain a COVID-19 negative certificate before arriving in China and are subject to a 14-day mandatory quarantine. Meanwhile many other countries closed borders, introduced travel restrictions and other health checks with flights from China, especially in the early months when COVID-19 cases in China were high.

As a result of these developments, Chinese airports saw a dramatic decline in both their aeronautical and non-aeronautical revenues, through having to cope with the consequences of restricted air services combined with the suppressed demand. Furthermore, some airports introduced rental waivers, in response to government policies, to give some relief to various other airport users, again affecting their non-aeronautical revenues. At the same time, the high fixed costs (capital and operating) of the airports, and the significant difficulties involved with the closing down of any of airport immovable assets, so overall airport profitability reduced considerably or losses were made. For example, net profits for January–March 2020 vs 2019 at Gaungzhou were US$9 mn vs US$35 mn; Shanghai (both airports) US$12 mn vs US$201 mn; Shenzhen US$18 mn vs US$25 mn; Xiaman US$0.4 mn vs US$17 mn. A mixed picture still existed in the period July–September (e.g. Gaungzhou US$15 mn vs US$25 mn in 2019; Shanghai US$-51 mn vs US$188 mn; Shenzhen US$13 mn vs US$25 mn; Xiaman US$13 mn vs US$20 mn). The profits of Beijing airports were also badly affected (e.g. January–June 2020/2019 US$-107 mn vs US$187 mn) (Reuters, 2020a).

In general, smaller airports tend to struggle more to achieve healthy profits and so a worse situation for smaller Chinese airports could be expected, although with the coronavirus case this needs to be weighed up against the benefits of not offering international services, which generally are expected to take longer to recover. In recognition of the challenges facing smaller airports at the end of April 2020 the CAAC announced plans to increase the subsidies that were already given to airports with less than two million passengers, and for the first time such subsidies were also increased for airports over two million passengers (Reuters, 2020b). As regards investment, at the peak of the coronavirus outbreak, most of the construction work on airports were halted. However, on March 26, 2020, the government announced that 68 projects of 81 airports under construction had been resumed, with all of the 30 major national airport projects coming out of temporary suspension (CAPA, 2020a). The government has also indicated that it still aims to develop 215 additional airports by 2035 and so are confident that in spite of the effects of the virus, the forecast traffic demand will return and moreover funding will be available (unlike at many other countries and airports suffering from the COVID-19 dire economic consequences).

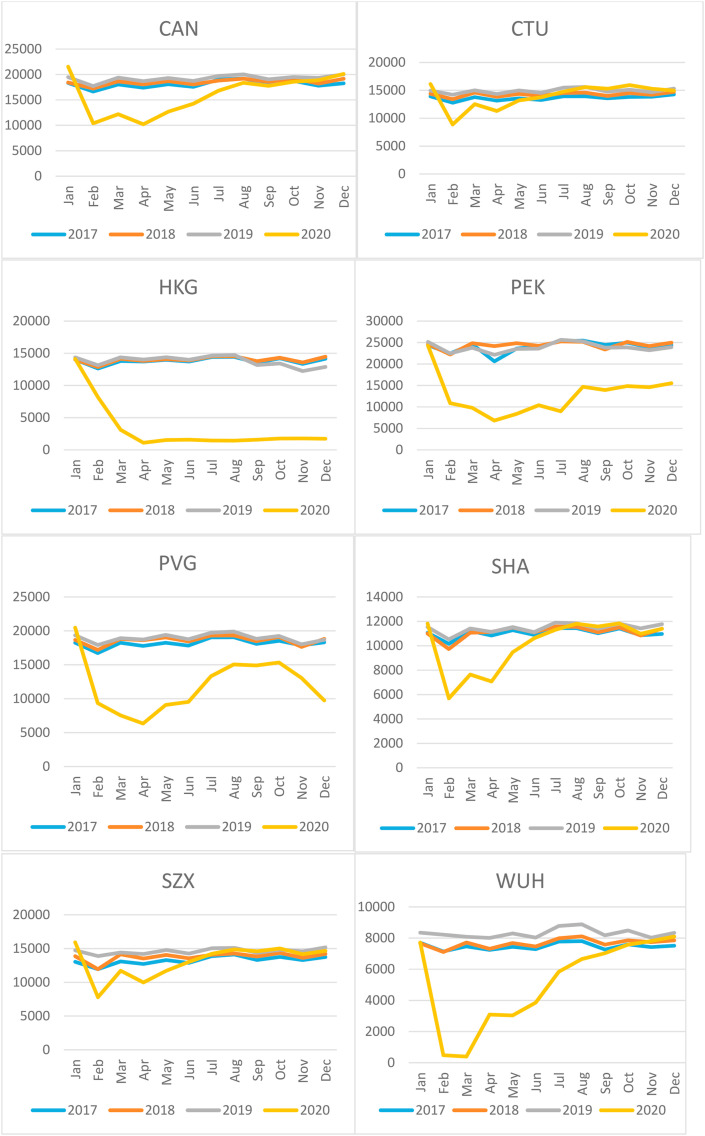

Fig. 24 looks specifically at traffic development at a few individual airports and for China's largest airport, Beijing Capital, there are a number of factors that have to be considered. First, with the opening of Beijing Daxing airport in September 2019, some traffic has already begun to be transferred there. Indeed, since its opening Daxing has operated as a hub for China United and also certain domestic services, for example, China Southern and China Eastern, have been shifted. However, on March 13, 2020, it was announced that all international traffic had to be transferred from Daxing to Capital to prevent the transmission of coronavirus. In the month of January in 2020, Capital had 24,000 outbound frequencies compared to 4000 at Daxing but by December the split was 16,000 at Beijing Capital and 12,000 at Daxing. Hence the decline in frequencies at Beijing Capital reflect both the presence of COVID-19 and some transfer of traffic to Daxing. Nevertheless, it is clear that Beijing Capital airport is one of the worst affected by COVID-19 which can largely be explained by the airport's high dependence on international and transfer traffic (around 10%). The airport closed its T1 in May 2020 to reduce its operating costs, but also to upgrade it (it reopened in September) and the airport's planned other capital expenditure in the short-run does not seem to have changed.

Fig. 24.

Frequencies at the sixth largest Chinese mainland airports, Wuhan airport and Hong Kong airport 2017–2020.

China's second largest airport is Shanghai Pudong and it is interesting to compare its fortunes with Shanghai Hongqiao (the eighth largest airport) since both serve the same region and are under common ownership. Hongqiao is ahead of Pudong in the road to recovery with a key constraining factor for Pudong being its higher than average share of international traffic (around 40%) which is larger than all the other major airports except Hong Kong.

The third largest airport is Guangzhou, which together with Shenzhen (fifth largest) serves the heavily populated Pearl River Delta conurbation of Southern mainland China, along with Hong Kong airport. These two mainland airports have experienced recent significant investment, especially since the 2019 anti-government protests at Hong Kong have raised some doubts about the ability of the city and airport to act as a major international travel hub in the future - even though in May 2020 a new Government plan was released outlining the aim to a establish Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area airport cluster by 2025 where Hong Kong's status as a major international hub would be enhanced (CAPA, 2020b). Both Guangzhou and Shenzhen airports have performed much better than Hong Kong airport and in September 2020 expansion work at Guangzhou airport began which includes a new terminal and two new runways. However, although Hong Kong is of a similar size to Guangzhou, it is very different in the manner that it is operated, the market and airlines that it serves, and the nature of traffic (with a much higher share of international and transfer traffic than other Chinese airports).

According to the airport's own passenger data, Hong Kong airport's passenger numbers declined to just 32,000 passengers in April 2020, and these have shown very little sign of recovery with the numbers in November 2020 totalling 51,000, down by 98% on the 5,027,000 passengers that were handled in November 2019. A major contributing factor may well be that the Hong Kong SAR had even stricter COVID-19 measures than mainland China (Boseley, 2020). However, the overall impact of the coronavirus outbreak is complex to gauge since the traffic had already declined from 75 million in 2018 to 72 million in 2019, primarily due to the anti-government protests which began in July 2019. As a result, the airport first introduced relief measures such as fee reductions and rental concessions/waivers way back in September 2019 targeted at airlines, retail and catering outlets, ground handling agents and others. It subsequently introduced further relief packages in February, March and April 2020 bringing the total relief aid to US$590 mn. The April package included an offer of the airport to purchase 500,000 air tickets in advance from the four home-based airlines to inject liquidity into the airlines upfront and to aid traffic recovery (Hong Kong Airport Authority, 2020a). The relief package has subsequently been extended several times and is now applicable until March 2021.

Such generous support and plummeting airport revenues due to the drastic reduction in passenger numbers has had a severe impact on the airport's finances. Moreover, on March 25, 2020, all transit/transfer services were suspended, also resulting in the closure of most shops and restaurants. This had a further detrimental consequence for both aeronautical and non-aeronautical revenues, as well as having major implications for the airlines operating such services. These services from Mainland China were once again allowed from August 15, but are still not available to Mainland China. It was hoped that on November 22 a travel bubble could be established between Hong Kong and Singapore, but this was postponed at the last minute because of a spike in COVID-19 cases in Hong Kong - it has now been pushed back until sometime in 2021. A similar bubble between Hong Kong and Mainland China had been proposed earlier in the year, but again abandoned because of a new COVID-19 wave. Nevertheless, in spite of the current low demand, work continues on the third runway, which is due to be fully operational by 2024. This should enable Hong Kong airport to remain at the heart of Asian traffic growth - not being surpassed, for example, by Beijing and Shanghai. Annual revenues and net profits at the airport up until March 2019 were down by 12% and 30% respectively, reflecting the unrest period and the early months of COVID-19. However during the next six months, revenues fell by 69% with a negative profit of US$-344 mn compared to US$497 mn in the previous year (Hong Kong Airport Authority, 2020b).

According to official Government statistics, Sichuan province, where Chengdu is located had only 564 COVID-19 cases and three deaths by late May 2020 and overall the airport (sixth largest in 2019) experienced a less pronounced drop in traffic compared to many of the other airports. As a consequence, carriers such as Chengdu based Sicuan Airlines (3U) have also been able to maintain higher traffic and capacity levels relative to many other Chinese based carriers. This compares to Hubei province, which has seen more than 68,000 confirmed cases and 4000 deaths. Hubei's capital Wuhan - the starting point of the coronavirus outbreak - illustrates the extreme case of an airport located in a region which was under total quarantine between January 23 and April 8. There was an almost total collapse in traffic when only aid and rescue flights were operated, and consequently, the road to recovery has followed a more pronounced upwards path but by the end of the year frequencies were only down 3% on 2019.

5. Conclusions

The aim of this paper was to analyse the impact of COVID-19 on Chinese air passenger markets through time by considering airline seats offered and passengers flown; airline revenues and average air fares; and airport frequencies. Overall it was found that those routes served by well financed/funded air carriers, those exposed to the lowest rates of COVID-19 infection and/or those that are seeing the least restrictive lockdowns and travel measures have been impacted least by the pandemic and are those that are most likely to rebound first.

It is very clear that not all air carriers have been impacted equally by the COVID-19 pandemic. Less well-financed/funded carriers whose networks are focussed on international markets, premium traffic and discretionary leisure travel have been found to be impacted most by the pandemic and are those that are likely to take the longest to recover. Conversely, better financed/funded airlines with a greater focus on domestic markets, non-discretionary traffic, and standard economy class fares have been found to be less severely impacted by the pandemic. Spring Airlines’ nimbleness as a large Shanghai-based LCC and its focus on domestic and intra-regional markets, has allowed it to rebound quicker and perform better than its peers during the observed period, even on the generally more restricted China to rest of Asia international markets.

In terms of Chinese airports, performance has varied according to airlines served, characteristics of the airport/city, and the severity of the outbreak. The experience of Chengdu has been contrasted with Wuhan for example, as has Hong Kong's with that of Guangzhou and Shenzhen. Reductions in traffic has caused very significant decreases in airport revenues and profits, especially for airports with large international traffic volumes such as those serving Beijing, Shanghai and Hong Kong. However, airport construction and capacity expansion have returned, indicating the government's optimism about the future.

As other regions and countries go through the different stages of their COVID-19 epidemics, this study has unearthed some useful indications from the Chinese experience for airports, airlines and route markets worldwide. Airports handling domestic traffic may fair better in the short term in countries where there is a lot of domestic traffic. Equally more diversified air carriers and route markets in terms of market segments served (i.e. those less reliant on international/intercontinental traffic) are also more likely to be less severely impacted by the pandemic and more likely to recover faster to pre-COVID-19 traffic and revenue levels.

This research has contributed to the body of knowledge by providing disaggregated evidence on the impact of COVID-19 on capacity and demand, including fares and revenue. The paper has linked the traffic volume and frequency to industry responses, mainly those of airlines and airports. One of the most significant global traffic markets (in ASK and RPK) has been investigated and most importantly this is the market from where the pandemic started. The research provides evidence on the scale of the disruption, but also on the possible pathways to recovery. It also opens the door for further research. For example, at a later stage, once the situation appears more stable, a causality analysis could be undertaken with the data to provide useful and future insight into the key factors that drove traffic patterns during the pandemic.

A primary limitation of this research is that it has not considered air cargo traffic despite the fact that it has been less severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic than passenger markets. It would be important for any follow-up research to consider whether combination carriers and route markets that have a more diversified mix of traffic will be better placed to deal with high impact external events such as a pandemic. There are also limitations in terms of the data. Sabre passenger demand, fare and revenue data was only available up to September 2020 at the time of this research. It was not possible therefore, particularly for the China to Europe market to observe the year 2020 as a whole, and how second waves during colder winter periods, particularly in Europe further hindered the air traffic recovery.

Author statement

Marina Efthymiou: Conceptualization; Methodology; Writing – Original Draft; Writing – Review and Editing.

Anne Graham: Conceptualization; Methodology; Formal analysis; Writing – Original Draft; Writing – Review and Editing.

Frankie O’Connell: Conceptualization; Methodology; Data curation; Writing – Original Draft; Writing – Review and Editing.

David Warnock-Smith: Conceptualization; Methodology; Formal analysis, Writing – Original Draft; Writing – Review and Editing.

Footnotes

China's GDP growth slowed from 6.8% to 6.0% between Q1 2018 and Q4 2019 (International Monetary Fund, 2020).

As one low-cost entity AirAsia and Thai AirAsia combined carried more passengers than Spring Airlines.

Appendix A. Top 10 O&D routes China Domestic, China to Europe and China to rest of Asia (by 2019 direct seats)

| China Domestic | No. |

O&D pair |

Origin Airport |

Destination Airport |

Seats 2019 (OAG) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

PEK-SHA |

Beijing Capital |

Shanghai Hongqiao |

4,058,511 |

|

| 2 |

CAN-PEK |

Guangzhou |

Beijing Capital |

3,344,164 |

|

| 3 |

CAN-SHA |

Guangzhou |

Shanghai Hongqiao |

3,190,835 |

|

| 4 |

SZX-PEK |

Shenzhen |

Beijing Capital |

3,153,649 |

|

| 5 |

CTU-PEK |

Chengdu |

Beijing Capital |

3,108,463 |

|

| 6 |

HKG-PVG |

Hong Kong International |

Shanghai Pudong |

2,235,541 |

|

| 7 |

PEK-HGH |

Beijing Capital |

Hangzhou |

1,771,067 |

|

| 8 |

CKG-PEK |

Chongqing |

Beijing Capital |

1,702,118 |

|

| 9 |

HKG-PEK |

Hong Kong International |

Beijing Capital |

1,693,507 |

|

| 10 | TAO-SHA | Qingdao | Shanghai Hongqiao | 1,060,063 | |

| China to Europe | 1 | HKG-LHR | Hong Kong International Apt | London Heathrow Apt | 926,984 |

| 2 | PEK-SVO | Beijing Capital Intl Apt | Moscow Sheremetyevo Apt | 471,525 | |

| 3 | PVG-FRA | Shanghai Pudong International Apt | Frankfurt International Apt | 458,007 | |

| 4 | PVG-SVO | Shanghai Pudong International Apt | Moscow Sheremetyevo Apt | 400,852 | |

| 5 | PEK-CDG | Beijing Capital Intl Apt | Paris Charles de Gaulle Apt | 399,445 | |

| 6 | PEK-FRA | Beijing Capital Intl Apt | Frankfurt International Apt | 360,507 | |

| 7 | PEK-MUC | Beijing Capital Intl Apt | Munich International Airport | 250,436 | |

| 8 | PEK-AMS | Beijing Capital Intl Apt | Amsterdam | 226,903 | |

| 9 | HKG-HEL | Hong Kong International Apt | Helsinki-Vantaa | 214,288 | |

| 10 | HKG-MUC | Hong Kong International Apt | Munich International Airport | 159,826 | |

| China to rest of Asia | 1 | HKG-TPE | Hong Kong International | Taipei | 3,984,287 |

| 2 | HKG-BKK | Hong Kong International | Bangkok | 2,455,248 | |

| 3 | HKG-MNL | Hong Kong International | Manila | 1,943,915 | |

| 4 | HKG-NRT | Hong Kong International | Tokyo Narita | 1,596,701 | |

| 5 | HKG-SIN | Hong Kong International | Singapore | 1,885,298 | |

| 6 | HKG-KIX | Hong Kong International | Osaka | 1,488,115 | |

| 7 | PVG-ICN | Shanghai Pudong | Seoul Incheon | 1,299,791 | |

| 8 | TAO-ICN | Qingdao | Seoul Incheon | 1,199,031 | |

| 9 | PVG-TPE | Shanghai Pudong | Taipei | 1,075,061 | |

| 10 | PVG-SIN | Shanghai Pudong | Singapore | 1,051,702 |

Appendix B. Top 20 air carriers China Domestic, China to Europe and China to rest of Asia (by passenger traffic 2019)

| China Domestic |

China to Europe |

China to rest of Asia |

||||||||||