Introduction

A highly anticipated COVID-19 vaccine has the potential to slow the pandemic in 2021. But a preponderance of misinformation, including conspiracy theories spreading through social media, has left much of the American public skeptical of vaccine candidates, and may undermine vaccine adherence.1 Up to 40% of Americans either do not intend to be vaccinated, or are unsure.2

Black Americans have borne a particularly disproportionate share of COVID-19 infections,3 and surveys have revealed higher rates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Black Americans relative to other racial/ethnic groups.2 Centuries of medical racism and subsequent medical mistrust among racial/ethnic minorities3 has left COVID-19 vaccine trials struggling to achieve diverse participation. This casts doubt on many communities’ ability to eventually achieve herd immunity.1 Efforts to increase trust among Black Americans may help alleviate these problems, but the relationships between race, COVID-19 beliefs, trust, and vaccine hesitancy are complicated.2 A richer understanding of these dynamics is crucial for diversifying participation in clinical trials and reducing vaccine hesitancy. We used nationally representative survey data from June 2020 to test the hypothesis that Black race would interact with medical trust to undermine COVID-19 vaccine willingness.

Methods

The study was deemed exempt by the University of Miami institutional review board. Qualtrics, partnering with Lucid, administered a survey from June 4 to 17, 2020 (just before US COVID-19 cases spiked in July), to a nationally representative quota sample of n = 1040 Americans that matched 2010 US Census records on sex, age, race, and income. The survey assessed participant demographics, political ideology, religiosity, and health and economic impacts of COVID-19, and contained psychometric scales used as unidimensional measures of perceived stress, conspiracy thinking (CT), denialism, and trust in health institutions (THI). Vaccine willingness was measured using a 5-point Likert scale, strongly disagree to strongly agree, to the question, “If a vaccine for COVID-19 becomes available I would be willing to take it.” We did not ask about factors that might increase vaccine willingness. We used Stata 16 to fit a multivariable mixed effects Tobit regression model of COVID-19 vaccine willingness with errors clustered by US state. A 2-sided P-value less than .05 was considered significant.

Results

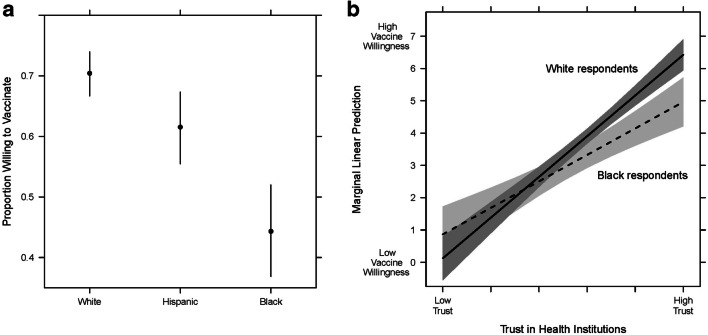

Only 63.5% of participants strongly agreed (36.6%) or agreed (26.8%) with being willing to take a COVID-19 vaccine, consistent with other surveys conducted in spring 2020, with significant variation by race/ethnicity: 70.4% for White, 61.5% for Hispanic/Latinx, and 44.3% for Black respondents (Fig. 1a). In the multivariable model, age-squared, household income, education, self-reported stress, and THI were all positively associated with vaccine willingness, while age, Black race, conservative political ideology, and CT were negatively associated with vaccine willingness (Table 1). Given the strong effect sizes for Black race, THI, and CT, we included interaction terms for Black and THI, and Black and CT. The Black-THI interaction term was negatively associated with vaccine willingness, meaning that the effect of THI on vaccine willingness was qualified by Black race. The marginal effects plot of vaccine willingness by THI (Fig. 1b) revealed that even at the highest levels of THI, Black respondents were significantly less willing to take a COVID-19 vaccine (i.e., more vaccine hesitant) than White respondents.

Fig. 1.

a Proportion of White, Hispanic, and Black respondents who strongly agreed or agreed with the statement, “If a vaccine for COVID-19 becomes available I would be willing to take it” in June 2020, and b marginal linear prediction of vaccine willingness at different levels of trust in health institutions (THI) for Black and White respondents. In b, at the lowest levels of THI, everyone expressed low vaccine willingness, while at the highest levels of THI, Black respondents expressed significantly less willingness than White respondents.

Table 1.

Multivariable Mixed Effects Tobit Regression Model of COVID-19 Vaccine Willingness among 1032* Nationally Representative Survey Participants in June 2020

| Characteristic | β | SE | Z | P-value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual-level fixed effects | |||||

| Gender: male | .038 | .139 | .27 | .786 | − .235 to .311 |

| Age | − .093 | .023 | − 4.02 | < .001 | − .138 to − .047 |

| Age-squared | .001 | .000 | 4.51 | < .001 | .001 to .002 |

| Identify as: Black or African American | − .505 | .208 | − 2.43 | .015 | − .913 to − .098 |

| Identify as: Hispanic or Latino | − .071 | .163 | − .44 | .663 | − .391 to .248 |

| Identify as: Asian American or Pacific Islander | − .360 | .350 | − 1.03 | .304 | − 1.046 to .326 |

| Identify as: Native American or American Indian | − .482 | .434 | − 1.11 | .267 | − 1.333 to .369 |

| Identify as: Other | − .477 | .551 | − .87 | .386 | − 1.556 to .602 |

| Annual household income | .090 | .046 | 1.97 | .049 | .000 to .180 |

| Education | .151 | .052 | 2.89 | .004 | .048 to .253 |

| Political ideology (liberal to conservative) | − .121 | .041 | − 2.93 | .003 | − .201 to − .040 |

| Religiosity | .035 | .055 | .63 | .530 | − .073 to .143 |

| COVID-19 health impact score | .042 | .052 | .80 | .426 | − .061 to .144 |

| COVID-19 economic disruption score | .286 | .149 | 1.92 | .054 | − .006 to .578 |

| Perceived stress (PSS-4 score) | .073 | .024 | 3.03 | .002 | .026 to .120 |

| Denialism scale | − .063 | .084 | − .75 | .450 | − .228 to .101 |

| Conspiracy thinking scale | − .417 | .089 | − 4.71 | < .001 | − .591 to − .244 |

| Trust in health institutions scale | 1.171 | .089 | 13.14 | < .001 | .996 to 1.345 |

| State with Republican Governor | − .054 | .134 | − .40 | .689 | − .316 to .209 |

| Interaction term: Black × Conspiracy thinking | .095 | .197 | .48 | .630 | − .291 to .480 |

| Interaction term: Black × Trust in health institutions | − .351 | .165 | − 2.13 | .034 | − .675 to − .027 |

| Constant | 4.875 | .620 | 7.86 | < .001 | 3.660 to 6.090 |

| State-level effects | |||||

| State-level constant | 3.10 × 10−34 | 2.92 × 10−19 | |||

| State-level error | 3.591 | .252 | 3.130 to 4.120 | ||

| Model log likelihood = − 1466.0824 | |||||

*Note: 8 cases from the original 1040 sample had missing covariate data that led to case exclusion

Discussion

This study expands our knowledge of how race is related to COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy by adjusting for personal traits such as stress, conspiracy thinking, and medical trust. Higher medical trust was associated with lower vaccine hesitancy, but public health officials and the media risk conflating demographics, conspiracy thinking, and medical trust in understanding public COVID-19 vaccine perceptions. The COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy expressed by Black respondents is much greater than other racial immunization disparities across the life-course.4 The difference is likely attributable to structural racism, which requires the medical establishment to demonstrate its trustworthiness to Black Americans5 and recognize medical mistrust as a rightful adaptation to historical dehumanization in order to begin to mitigate vaccine hesitancy.3 Health education programs focused on building medical trust may underperform if they do not address structural racism. Because third-party survey respondent pools may be less generalizable to the Black and Hispanic population,6 the interaction between trust and vaccine willingness may be stronger than we detected. Difficult community dialogues may be a crucial first step toward engaging communities of color and promoting COVID-19 vaccine acceptance.

Funding

This work was supported by the University of Miami through a 2020 COVID-19 Rapid Response Award by the Office of the Vice-Provost for Research, and a 2020 COVID-19 Rapid Response Award by the College of Arts and Sciences, to Drs. Stoler, Klofstad, and Uscinski (PI). The sponsor had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Data Availability

Study protocol, data set, and statistical code: Available from Dr. Justin Stoler (e-mail, stoler@miami.edu).

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Schaffer DeRoo S, Pudalov NJ, Fu LY. Planning for a COVID-19 vaccination program. JAMA. 2020;323(24):2458–2459. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher KA, Bloomstone SJ, Walder J, Crawford S, Fouayzi H, Mazor KM. Attitudes toward a potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: a survey of U.S. adults. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Manning KD. More than medical mistrust. The Lancet. 2020;396(10261):1481–1482. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32286-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu P-j, O’Halloran A, Williams WW, Lindley MC, Farrall S, Bridges CB. Racial and ethnic disparities in vaccination coverage among adult populations in the U.S. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2015;49(6, Supplement 4):S412–S425. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warren RC, Forrow L, Hodge DA, Truog RD. Trustworthiness before trust — Covid-19 vaccine trials and the Black community. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(22):e121. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2030033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kennedy C, Mercer A, Keeter S, Hatley N, McGeeney K, Gimenez A. Evaluating online nonprobability surveys. In. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Study protocol, data set, and statistical code: Available from Dr. Justin Stoler (e-mail, stoler@miami.edu).