SUMMARY

A-to-I RNA editing, catalyzed by ADAR proteins, is widespread in eukaryotic transcriptomes. Studies showed that, in C. elegans, ADR-2 can actively deaminate dsRNA, whereas ADR-1 cannot. Therefore, we set out to study the effect of each of the ADAR genes on the RNA editing process. We performed comprehensive phenotypic, transcriptomics, proteomics, and RNA binding screens on worms mutated in a single ADAR gene. We found that ADR-1 mutants exhibit more-severe phenotypes than ADR-2, and some of them are a result of non-editing functions of ADR-1. We also show that ADR-1 significantly binds edited genes and regulates mRNA expression, whereas the effect on protein levels is minor. In addition, ADR-1 primarily promotes editing by ADR-2 at the L4 stage of development. Our results suggest that ADR-1 has a significant role in the RNA editing process and in altering editing levels that affect RNA expression; loss of ADR-1 results in severe phenotypes.

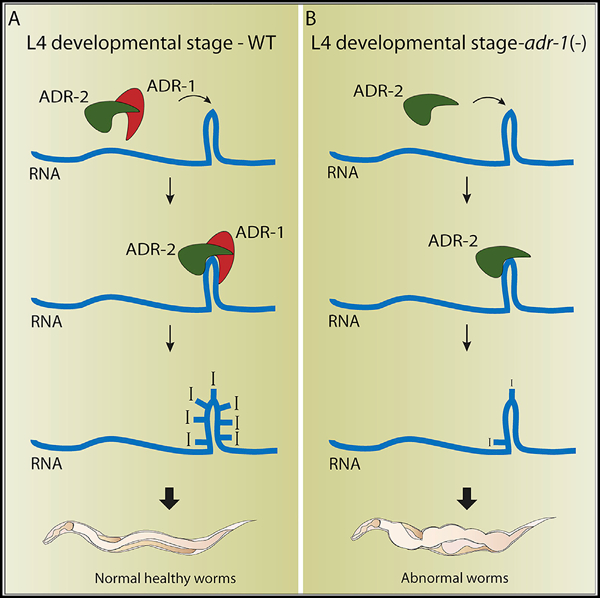

Graphical Abstract

In Brief

Ganem et al. report that the C. elegans enzymatic-inactive ADR-1 regulates A-to-I RNA editing by directing editing by ADR-2, mainly at the L4 developmental stage. Changes in RNA editing levels severely affect normal development by changing RNA levels, but not protein levels.

INTRODUCTION

Adenosine-to-inosine (A-to-I) RNA editing is a conserved process in which adenosine deaminases that act on RNA (ADAR) enzymes convert adenosine to inosine within double-stranded regions of RNA (Bass, 2006). Inosine is read as guanosine by the translation machinery and, thus, can change protein amino acid content and function. Several examples of protein changes in the human brain have been described (Burns et al., 1997; Pullirsch and Jantsch, 2010; Werry et al., 2008); however, most editing sites in humans are in non-coding regions of the transcriptome (mainly in Alu repeats) (Athanasiadis et al., 2004; Barak et al., 2009; Blow et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2004; Levanon et al., 2004; Li et al., 2009b). In mammals, ADARs are essential; knockout mice are either embryonically lethal (ADAR1) or lethal shortly after birth (ADAR2) (Wang et al., 2000; Higuchi et al., 2000). However, in model organisms, such as C. elegans and D. melanogaster, strains that lack all RNA editing are viable, although they exhibit behavioral and anatomical defects (Tonkin et al., 2002; Palladino et al., 2000).

Many A-to-I editing sites have been identified in the C. elegans transcriptome by high-throughput RNA sequencing, and most of them are located in introns and other non-coding regions (Goldstein et al., 2017; Whipple et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2015). RNA editing in C. elegans is developmentally regulated. The overall frequency of RNA editing is greater in embryos than it is in other stages (Zhao et al., 2015). However, there are genes that undergo frequent RNA editing at the L4 developmental stage and almost no editing at the embryo stage, despite the transcripts being expressed to a similar level in both stages (Goldstein et al., 2017). This points to the fact that the editing activity in C. elegans is highly regulated.

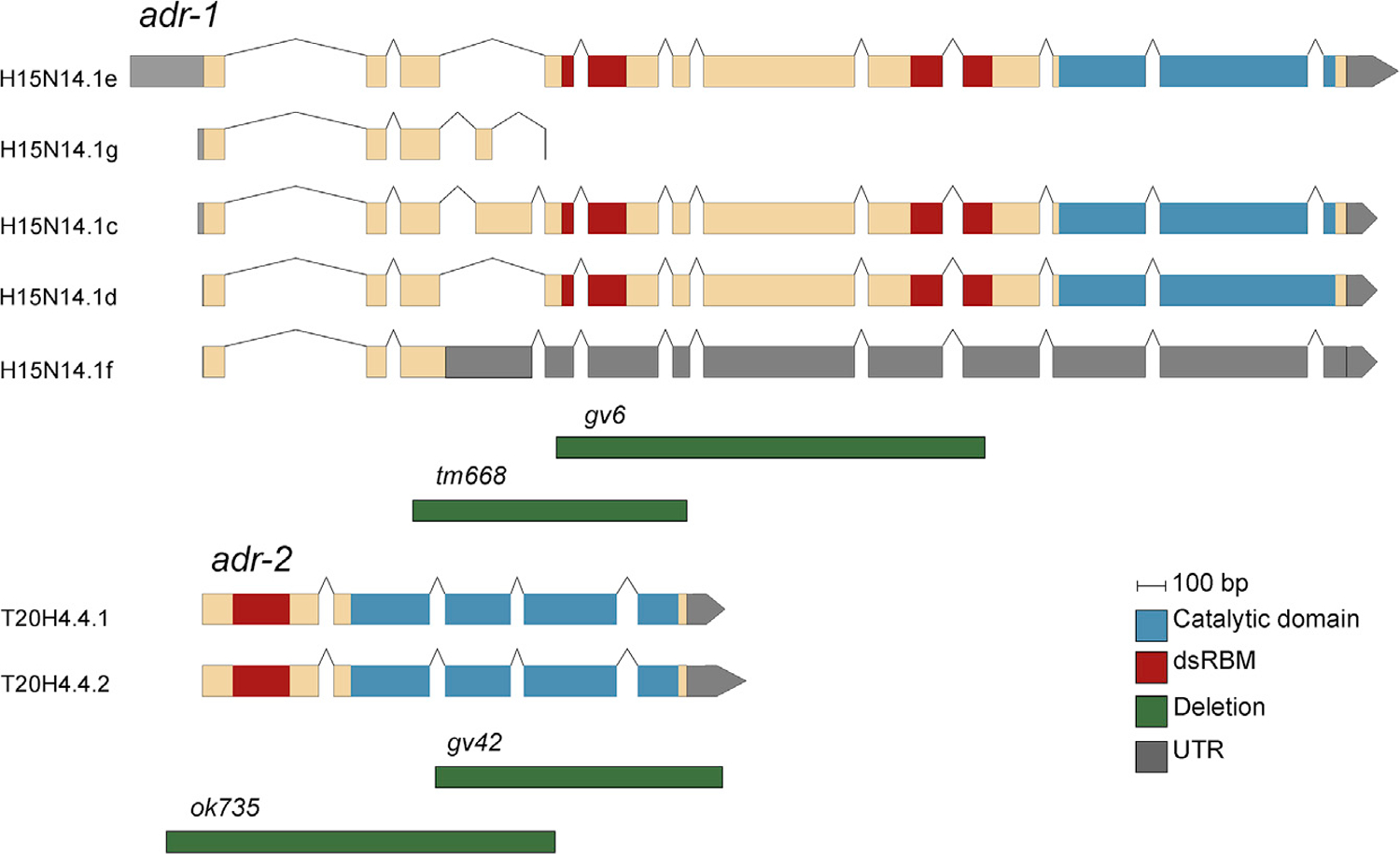

C. elegans possess two ADAR genes: adr-1 and adr-2. Both proteins share the common ADAR enzyme structure: highly conserved C-terminal deaminase domain and variable number of N-terminal double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) binding motifs (two double-stranded RNA-binding domain [dsRBD] in ADR-1 and one in ADR-2; Figure 1) (Tonkin et al., 2002). However, ADR-2 is the only active adenosine deaminase in C. elegans, as knockout of adr-2 abolishes all A-to-I RNA editing (Washburn et al., 2014). On the other hand, ADR-1 acts as a regulator of ADR-2, regulating editing efficiency by interacting with ADR-2 and with ADR-2 targets through its dsRNA binding domains (Rajendren et al., 2018; Washburn et al., 2014). Expression analysis of GFP-tagged ADR-1 revealed that it is expressed mainly in the nervous system and developing vulva, but expression occurs in all developmental stages (Tonkin et al., 2002). Worms harboring deletions in both adr-1 and adr-2 genes are viable but have been reported to exhibit phenotypes that include chemotaxis defects, altered life span, and decreased expression of transgenes (Knight and Bass, 2002; Sebastiani et al., 2009; Tonkin et al., 2002). Worms harboring a specific mutated adr-1 allele were also shown to have a mild protruding-vulva (Pvl) phenotype (Tonkin et al., 2002).

Figure 1. Schematic View of adr-1 and adr-2 Genes and Isoforms and the Deletions That Were Used in This Study.

The genes and known isoforms are represented in their relative lengths. Double-strand RNA binding motifs (dsRBMs) regions are shown in red, and the deamination catalytic domains are shown in blue. The deletion alleles (green) are scaled and positioned to reflect the area of deletion in the genes; adr-1 gv6 (1,560-bp deletion) and tm668 (967-bp deletion), adr-2 gv42 (1,013-bp deletion), and ok735 (1,371-bp deletion). See also Figures S1 and S2 and Data S1.

Although thousands of editing sites were found in C. elegans (Goldstein et al., 2017; Whipple et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2015), most of those sites are located in non-coding regions and are, therefore, hard to link to the phenotypes of ADAR mutant worms. A slight general reduction in expression of C. elegans genes that undergo editing in 3′ UTRs occurs in worms harboring deletions in both adr-1 and adr-2 (Goldstein et al., 2017); however, most of those changes were not directly linked to phenotypic consequences. Recently, it was shown that the gene clec-41, which is edited in the 3′ UTR, is downregulated in neural cells lacking adr-1 or adr-2. Furthermore, a reduction in clec-41 contributes to the chemotaxis defects of worms lacking adr-2 (Deffit et al., 2017). Interestingly, mutations in RNAi genes in worms harboring mutations in adr-1 and adr-2 can rescue the chemotaxis and life span phenotype of the worms (Sebastiani et al., 2009; Tonkin and Bass, 2003), implicating RNAi involvement in the RNA-editing function. However, the specific transcripts that are important for those phenotypes and are altered by RNAi are unknown. Furthermore, it is still unknown what the main function of RNA editing is in C. elegans. There were some predictions of changes in protein structure (Goldstein et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2015) caused by editing in coding regions of genes, although that was shown on only a handful of genes, and the changes in protein structure were not validated. A new function for RNA editing emerged from studies in mammals, in which mammalian ADAR1 was implicated in preventing aberrant activation of the innate immune response from self-produced dsRNAs (George et al., 2016; Liddicoat et al., 2015; Mannion et al., 2014). It is possible that, in C. elegans, RNA editing has a similar function to prevent protection mechanisms, such as RNAi, in attacking self-produced RNA (Ganem and Lamm, 2017; Reich et al., 2018). In that case, the phenotypes observed in ADAR mutants might result from changes in the RNA level and not necessarily in the protein level.

Many of the studies done so far on C. elegans examined phenotypes, editing levels, and expression changes in worms harboring mutations in both adr-1 and adr-2 genes (for example, Goldstein et al., 2017; Tonkin et al., 2002; Whipple et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2015). Although some of these previous studies indicated that a lack of either ADAR gene resulted in chemotaxis and life-span defects (Sebastiani et al., 2009; Tonkin et al., 2002), ADR-1 probably affects the expression and function of edited genes and the severity of the phenotypes observed in a different manner than ADR-2. In addition, ADAR genes might have functions beyond RNA editing. For example, in mice, ADARs were shown to affect splicing, independent of their editing functionality (Solomon et al., 2013), and ADAR1 was found to inhibit Staufen-mediated mRNA decay, independent of its A-to-I editing function (Sakurai et al., 2017). To understand the contribution of each of the C. elegans ADAR genes to the RNA editing process, gene regulation, and the phenotypes exhibited in ADAR-mutant worms, we performed a comprehensive phenotypic, transcriptomics, and proteomics analysis on worms harboring mutations in adr-1 or adr-2 separately. We found that the phenotypes observed in adr-1 mutants are more severe, and some are distinct from those we observed in adr-2 mutants. We found that both genes affect the expression of edited genes, but the effect of ADR-1 is much more prominent. Editing still occurs in adr-1 mutants; however, the number of editing sites is reduced significantly at the L4 developmental stage. In addition, edited genes are also a significant portion of genes bound by ADR-1 either directly or indirectly. These results implicate ADR-1 as an important component of the RNA-editing process and suggest that changes in the levels of editing cause more developmental defects than does a complete lack of editing. Our results also suggest that the main function of ADARs and RNA editing is to regulate RNA expression and not the protein content in a cell.

RESULTS

Previous studies suggested that ADR-1 is not necessary for the editing process and is mostly a regulator of ADR-2 activity (Rajendren et al., 2018; Tonkin et al., 2002; Washburn et al., 2014). Editing is still observed in adr-1 mutants, although at different levels (Tonkin et al., 2002; Washburn et al., 2014). To explore the function of adr-1 and adr-2 in the editing process separately, we performed phenotypic, transcriptomics, and proteomics analyses on two deletion mutations for each gene. Both deletions of the adr-2 gene—removing either the deaminase domain or most of the protein (Figures 1 and S1; Tonkin et al., 2002)—were expected to result in a non-functional protein. As expected, we did not observe editing in mutants containing either one of those deletions (Data S1). ADR-1 has five annotated isoforms (Figure 1). Two isoforms are predicted to give rise to truncated proteins that do not contain either the dsRNA-binding domains or the deaminase domain. The dsRNA-binding domains in ADR-1 were shown to be required to regulate editing by ADR-2 (Rajendren et al., 2018; Washburn et al., 2014), and both available deletions completely delete or disrupt the dsRNA-binding domains (Tonkin et al., 2002; Washburn et al., 2014). Indeed, we observed changes in the editing levels in both deletion mutants, and as expected, editing was not completely abolished (Data S1).

adr-1 Mutant Phenotypes Are More Severe Than Those Observed in adr-2 Mutants

Worms harboring mutations in either or both adr-1 and adr-2 were previously shown to have reduced life-span and chemotaxis defects (Sebastiani et al., 2009; Tonkin et al., 2002). We, therefore, sought to explore whether both genes contributed equally to those phenotypes. If those phenotypes are a result of abolished editing, we expected to observe the same phenotypes in adr-2 mutants and, to a lesser extent, in adr-1 mutants. Chemotaxis experiments that were done by Tonkin et al. (2002) were repeated but with two deletion mutations for each of the genes, instead of one. We received similar results, with all mutants having chemotaxis defects (Figure S2). The chemotaxis defects were restored to normal in transgenic worms harboring FLAG-ADR-1 in an adr-1-mutant background (Washburn et al., 2014) (Figure S2). These results are in line with a study that found that both ADR-1 and ADR-2 affect expression of the clec-41 gene in neural cells, and overexpressing clec-41 in adr-2 mutants rescues the chemotaxis defect (Deffit et al., 2017). Interestingly, we observed an upregulation of clec-41 in adr-1 mutant worms in the embryo stage, but not in the L4 stage and not in adr-2 mutants (see below). This upregulation was also observed previously in L1 worms (Deffit et al., 2017). However, in neural cells, clec-41 was shown to be downregulated in adr-1 mutants (Deffit et al., 2017), suggesting that ADR-1 and ADR-2 may provide tissue-specific gene regulation in addition to development-specific gene regulation.

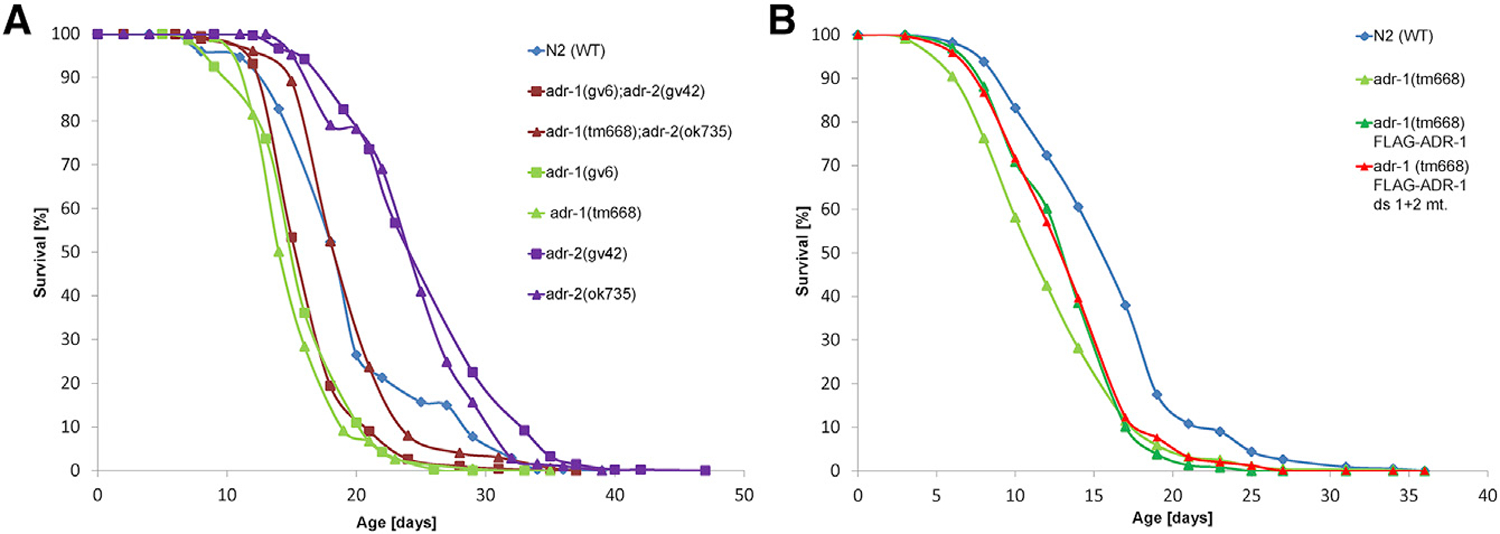

In addition, we performed life-span experiments on worms with deletions in both adr genes and worms with a deletion in a single adr gene. Strains harboring mutations in both adr-1 and adr-2 had reduced life spans or life spans similar to wild-type worms (Figure 2A). Surprisingly, we found that both deletion strains of adr-1 significantly reduce life span, whereas both strains with deletions in adr-2 significantly extended the life span compared to wild-type worms (Figure 2A). Strains carrying the extra-chromosomal array FLAG-ADR-1 in an adr-1-deletion background were able to slightly rescue the life-span phenotype of adr-1 mutation (Figure 2B). Interestingly, strains carrying a FLAG-ADR-1 with mutation in the dsRNA-binding domains (dsRBM) were able to rescue the life-span phenotype as well as wild-type ADR-1, suggesting that either the ability of ADR-1 to promote life span is independent of dsRNA binding or, possibly, mutant ADR-1 still has the ability to bind mRNAs other than the edited mRNAs that were previously shown to have disrupted ability to interact with the ADR-1 dsRBM mutant (Washburn et al., 2014).

Figure 2. adr-1 and adr-2 Mutants Have Opposite Life-Span Phenotypes.

(A) The life span of the mutant worms was followed, and the mean survival curves are presented for N2 (wild type [WT]), adr-1(gv6)I, adr-1(tm668)I, adr-2(gv42)III, adr-2(ok735)III, adr-1(gv6)I; adr-2(gv42)III and adr-1(tm668)I; adr-2(ok735)III. Mutations in adr-1 gene (adr-1(gv6)I or adr-1(tm668)I) reduce the life span of the worm compared with that of the WT worms, whereas mutation in adr-2 gene (adr-2(gv42)III or adr-2(ok735)III) extend the life span of the worm compared with that of the WT worms. Mutants for both genes have the same pattern as the WT worms.

(B) The mean survival curves are presented for WT, adr-1 (tm668), and the rescue strains adr-1 (tm668) FLAG-ADR-1: adr-1(tm668) I blmEx1[ 3XFLAG-adr-1 genomic, rab3::gfp::unc-54] and adr-1 (tm668) FLAG-ADR-1 ds1+2 mutant: adr-1(tm668) I blmEx1 (3XFLAG-adr-1 genomic with mutations in dsRBD1 [K223E, K224A, and K227A], and dsRBD2 [K583E, K584A, and K587A], rab3::gfp::unc-54). Both transgenic adr-1 rescue strains have life spans extended more than adr-1(tm668). Each experiment was repeated at least five times.

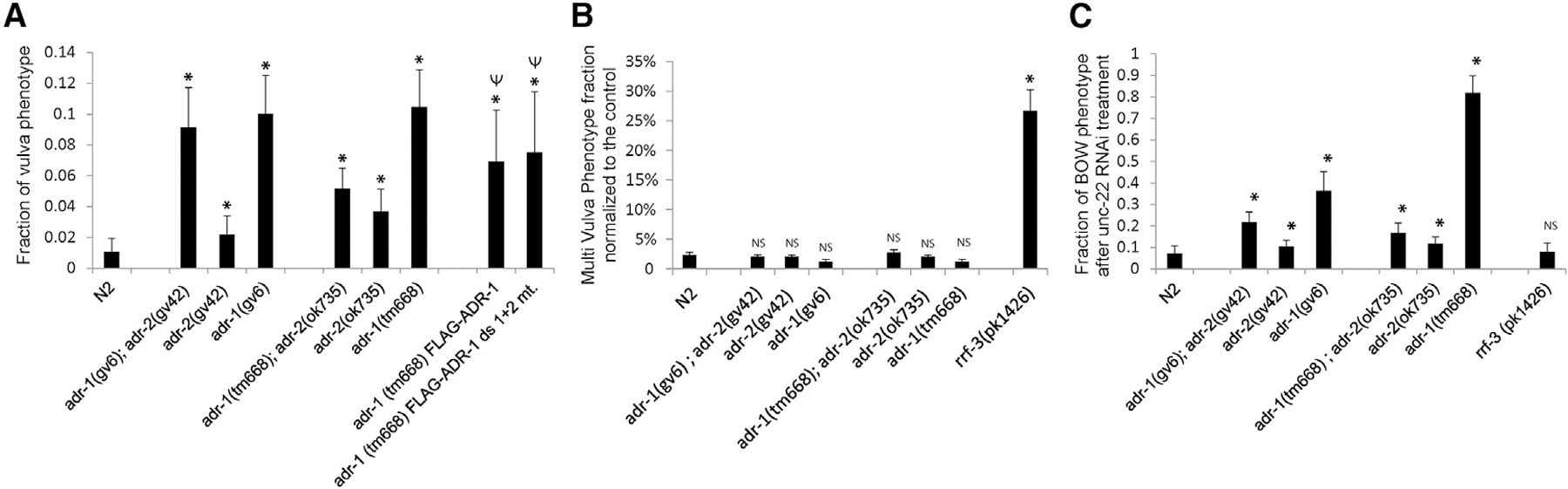

Previously, adr-1 was shown to be highly expressed in the vulva, and one of the adr-1 deletion strains exhibited a slight Pvl phenotype (Tonkin et al., 2002). To study whether that phenotype is strain specific because of a second mutation in a close gene or because of lack of adr-1, we counted the fraction of worms with the Pvl phenotype in all strains. We found a significant Pvl phenotype in all mutant strains, compared with wild-type strains, although the phenotype fraction from total worms was very low (less than 10% in all strains) (Figure 3A). ADR-1 mutants had the highest Pvl phenotype fraction, which was significantly reduced in transgene worms with FLAG-ADR-1 and FLAG-ADR-1 with dsRBM mutations (Figure 3A). We conclude that all ADAR mutants have developmental phenotypes, although ADR-1 seems to be more important for normal development than ADR-2 is.

Figure 3. adr-1 Mutants Have High Frequency of Vulva Abnormalities.

(A) ADAR-mutant strains were scored for pvl phenotype, and the fraction of worms presenting the phenotype from total worms is presented. The p value was calculated with a two-sample, unequal-variance, heteroscedastic t test; *p < 0.01 compared with WT; Ψp < 0.01 compared with adr-1(tm668)I.

(B) Worms were subjected to lin-1 RNAi. Multivulva phenotypes were scored at the first day of egg laying, and the fraction of worms exhibiting the phenotype from total worms is presented. Each experiment was repeated at least three times, and the standard deviation is presented by error bars. The p value was calculated with a two-sample, unequal-variance, heteroscedastic t test; *p < 0.01 compared with WT. NS, nonsignificant p value.

(C) Worms were subjected to unc-22 RNAi, and the fraction of worms presenting the bag of worms phenotype is presented. The p value was calculated by two-sample, unequal-variance, heteroscedastic t test; *p < 0.01 compared with WT. Each experiment was repeated at least three times, and the standard deviation is shown by error bars.

We previously suggested that downregulation of genes in ADAR mutants could be a consequence of the antagonistic relationship between RNA editing and RNAi (Goldstein et al., 2017). The possibility that ADAR genes and RNA editing itself are antagonistic to the RNAi process was raised previously because editing and RNAi both involve dsRNA substrates, because transgene silencing was observed in ADAR double mutants, and because of changes in the amount of siRNAs generated in wild-type worms and those lacking both ADARs (Goldstein et al., 2017; Knight and Bass, 2002; Reich et al., 2018; Tonkin and Bass, 2003; Warf et al., 2012; Whipple et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2011). Hypersensitivity to exogenous RNAi is a phenotype related to the ERI/RRF-3 endogenous RNAi pathway (Simmer et al., 2002), which is also reflected by transgene silencing. Therefore, hypersensitivity to RNAi was previously tested in several ADAR mutants (Knight and Bass, 2002; Ohta et al., 2008), which did not show hypersensitivity. We tested hypersensitivity to RNAi in all ADAR single and double mutants by triggering exogenous RNAi by feeding the worms with bacteria producing dsRNA against lin-1 or unc-22 genes (Simmer et al., 2002) and scoring the phenotype. We did not observe high enrichment of the multivulva phenotype in all ADAR mutant worms as compared with wild type when triggering RNAi against lin-1 (Figure 3B). As expected, rrf-3 mutant worms, which are hypersensitive to RNAi, have a significantly high fraction of the phenotype (Figure 3B). Triggering unc-22 RNAi, we expected a twitching phenotype, and in observing a strong twitching phenotype, we also noticed a new phenotype of the bag of worms (Figure 3C). The bag of worms phenotype was observed in a high fraction in adr-1 mutant worms and, to a lesser extent, in the adr-1;adr-2 double mutants and in adr-2 mutants. This phenotype is not a result of hypersensitivity to RNAi because it was not enriched in rrf-3 mutants (Figure 3C). We conclude that this bag of worm phenotype and the pvl phenotype are specific to adr-1 and might be a result of a different function of ADR-1, distinct from RNA editing.

Both ADR-1 and ADR-2 Affect Expression of Genes Edited at Their 3′ UTR

Previously, we demonstrated that the expression of genes with edited 3′ UTRs is slightly reduced in worms harboring deletions in both ADAR genes (Goldstein et al., 2017). The list of genes that are edited at their 3′ UTR was based on a screen for editing sites in non-repetitive regions in the transcriptome. In total, 77 genes with 3′ UTR-edited sites were identified (Goldstein et al., 2017). However, many edited sites were not included in the list, even though they are in a very close proximity to the 3′ UTR annotation of genes. These include genes that were biochemically identified by others to be edited at their 3′ UTR, for example, alh-7 and C35E7.6 (Morse et al., 2002; Morse and Bass, 1999). To extend the list of genes edited at their 3′ UTR, we manually annotated the edited sites in non-repetitive regions that are in proximity to genes. We added to the list, genes in which multiple editing sites are in the same orientation as the gene and in very close proximity to their annotated 3′ UTR or within the 3′ UTR, based on the newest version of Wormbase (see STAR Methods). Overall, we added 58 genes, and the list now includes 135 genes (Table S1). To re-examine the conclusion regarding expression levels of genes edited in 3′ UTRs in worms harboring deletions in both adr-1 and adr-2, we reanalyzed the expression data from Goldstein et al. (2017). We observed similar results with the 135 genes; their expression levels were slightly reduced compared with all genes in both embryo and L4 developmental stages (p < 0.003 calculated by Welch two-sample t test analysis for genes with a padj value < 0.05), suggesting that the newly identified genes edited in 3′ UTRs are bona fide ADAR-regulated genes (Figure S3).

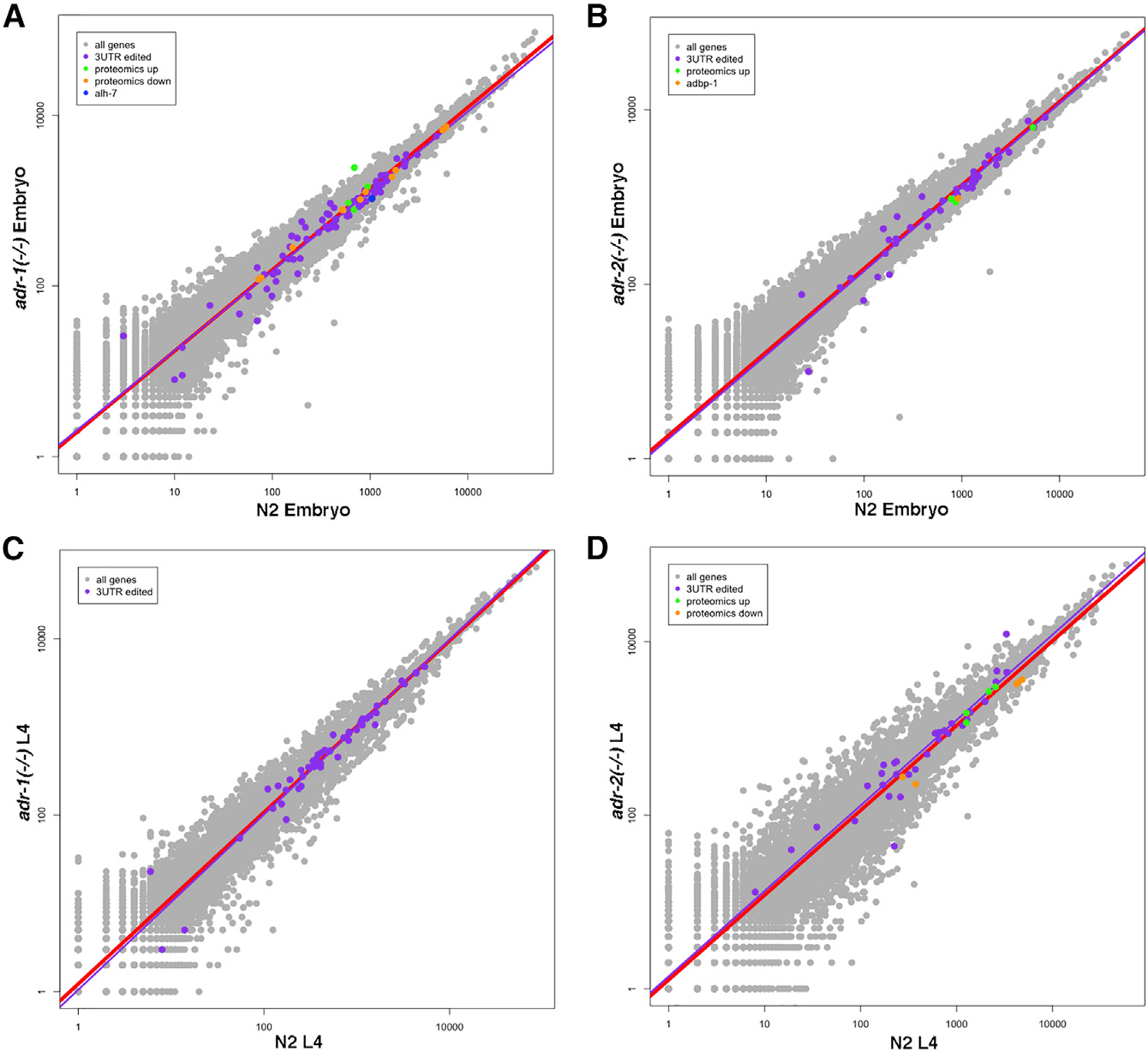

To study whether the expression levels of 3′ UTR-edited genes are affected in the single-deletion mutants, we generated RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data from three biological replicates of each of the strains and the wild-type strain in the embryo and L4 developmental stages. We observed the tendency for reduced expression of 3′ UTR-edited genes in all adr-1 and adr-2 mutants in the embryo stage (Figures 4A and 4B; p < 2.2e—16 for adr-1 (gv6), p = 0.002 for adr-1 (tm668), p < 0.002 for adr-2 (gv42), and p = 2.5e—05 for adr-2 (ok735)). However, the expression of 3′ UTR-edited genes does not change in all single-ADAR mutants in the L4 developmental stage (Figures 4C and 4D). This is in contrast to what we observed before in the double mutants (Goldstein et al., 2017). Thus, the effect of ADAR mutations on the expression of 3′ UTR-edited genes is stronger in the embryo stage than in the L4 developmental stage.

Figure 4. Genes Edited at Their 3′ UTR Are Downregulated in adr-1 and adr-2 Mutants at the Embryo Stage.

Log-scale plots presenting gene expression in wild-type (N2) worms versus adr-1 mutant worms (A and C) or adr-2 mutant worms (B and D) at the embryo stage (A and B) and at the L4 stage (C and D). Every dot in the graphs represents a gene. Red line is the regression line for all genes. The 3′ UTR-edited genes with significant padj value are in purple, and their regression line is presented in purple. Downregulated genes found by the proteomics analysis are in orange, and upregulated genes are in green. Alh-7 gene is downregulated in adr-1 mutants at the embryo stage in all analyses (blue in A). Adbp-1 gene is downregulated in adr-2 mutants in all analyses at the embryo stage (orange in B). See Figures S3, S6, and S7 and Tables S1, S2, and S5.

ADR-1 Affects the Expression of Edited Genes

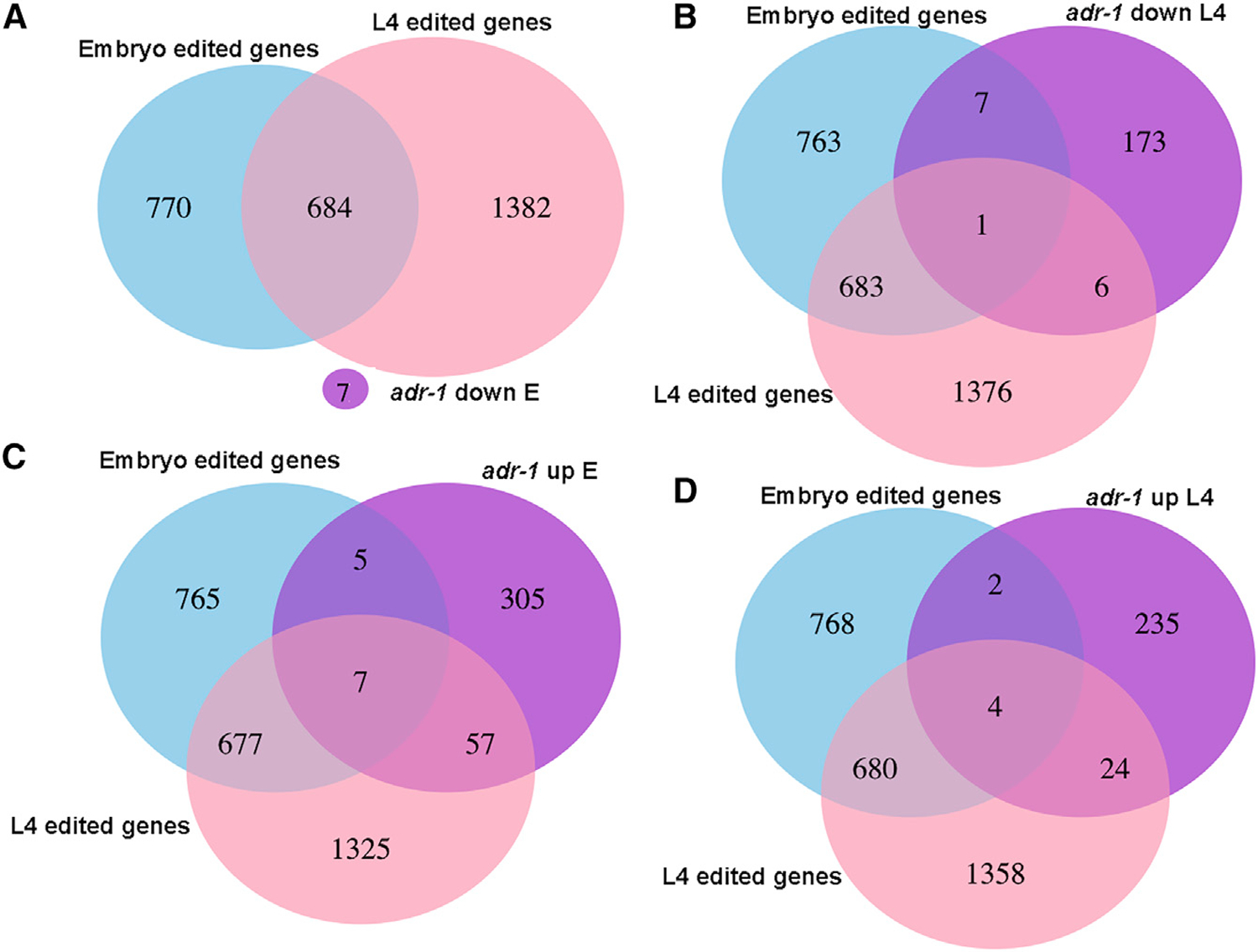

To further explore the expression of genes in adr-1 and adr-2 mutants, we identified the genes with a 2-fold or greater change in expression and a significant adjusted p value after Benjamini-Hochberg correction in each of the single-ADAR mutants in each developmental stage. We further shortened the list by including only genes that were significantly differentially expressed in both deletion mutations for each gene (Table S2) to avoid allele-specific background effects on gene expression. We found more upregulated than downregulated genes in both ADAR mutants in all developmental stages (Table S2) with significant overlap (p < 0.01 calculated by hypergeometric distribution and by the chi-square test) of differentially expressed genes between the embryo and L4 developmental stages (Figure S3). There is also a very significant overlap (p < e—5) between differentially expressed genes in adr-1 mutants and adr-2 mutants in all stages (Figure S4). However, 3′ UTR-edited genes were not a substantial part of the differentially expressed genes in either ADAR mutants (p value not significant; Figure S4). To explore whether genes edited in regions other than the 3′ UTR are differentially expressed in ADAR mutants, we compared the genes differentially expressed in each ADAR mutant and genes edited at the embryo or L4 developmental stages (described in Goldstein et al., 2017). We did not find a significant overlap between differentially expressed genes in adr-2 mutants and genes edited at L4 or at embryo stages (non-significant p value; Figure S4). Surprisingly, a significant portion of the upregulated genes in adr-1 mutants were genes edited at the L4 stage (p < 0.01; Figure 5). Downregulated genes in adr-1 mutants were not enriched for edited genes (non-significant p value; Figure 5). These results suggest that adr-1 not only affects the level of editing but also the expression of edited genes.

Figure 5. Significant Portions of Genes That Are Edited at L4 Stage Are Upregulated in adr-1 Mutants.

Venn diagrams presenting the intersections between edited genes at the embryo or L4 developmental stages, and (A) genes with their expression downregulated at embryo stage in adr-1 mutants.

(B) Genes with their expression downregulated at the L4 stage in adr-1 mutants.

(C) Genes with their expression upregulated at embryo stage in adr-1 mutants.

(D) Genes with their expression upregulated at the L4 stage in adr-1 mutants.

See Figure S4.

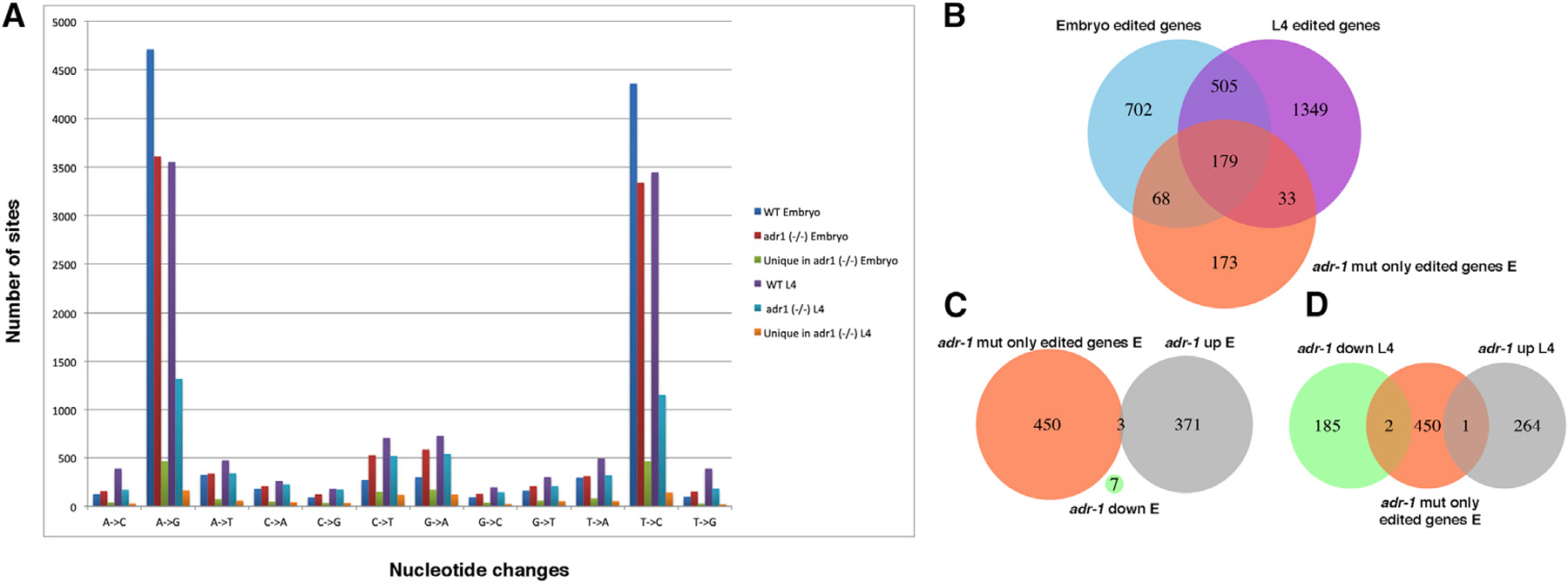

ADR-1 Role in Regulating RNA Editing Is Stronger at the L4 Stage

The increased expression of edited genes and the alterations in editing levels in adr-1 mutants suggests that ADR-2 editing of these genes is assisted by ADR-1 and may be important to stabilize gene expression. As for the lack of connection between the downregulated genes in the adr-1 mutant worms and editing in wild-type worms, it is possible that these downregulated genes contain editing sites in the adr-1 mutants and not in wild-type worms. This would suggest that ADR-1 also has a role in binding RNA and protecting or preventing the RNA from the editing by ADR-2. Therefore, new edited sites, ‘‘the protected sites,’’ should emerge in the high-throughput sequencing data sets obtained in the absence of ADR-1. To test that hypothesis, we performed a screen to identify editing sites in adr-1 mutants, similar to Goldstein et al. (2017), with the difference that only nucleotide changes that appeared in both adr-1 mutant alleles were considered. When counting the number of nucleotide changes that were identified in adr-1 mutants, surprisingly, we found a significant reduction in the amount of editing sites identified in adr-1 mutants at the L4 developmental stage compared with the embryo stage (Figure 6A; p < 0.01 calculated by Fisher exact test; Table S3). Next, we tested whether there are editing sites in adr-1 mutants that are not present in wild-type worms by comparing the lists of nucleotide changes. Although the number of editing sites that are only present in adr-1 mutants was not above the background of the other nucleotide changes at the L4 stage, we found an enrichment of editing sites that are present only in the adr-1 mutants at the embryo stage (Figure 6A; Table S3). To further study those sites, we compared genes with editing sites that are only edited in adr-1 mutants at the embryo stage to edited genes found in wild-type worms. We found that most of the genes with editing sites unique to adr-1 mutants have other sites that are edited in wild-type worms (Figure 6B). In addition, these genes do not have a significant change in expression in adr-1 mutants (Figures 6C and 6D). Overall, these results suggest that ADR-1 does not protect the dsRNA from being edited by ADR-2 but, rather, directs and enhances ADR-2 editing, especially at the L4 developmental stage. This is in line with our findings that many genes that are upregulated in adr-1 mutants are only edited at the L4 developmental stage (Figure 5).

Figure 6. Most of the Editing Sites That Appear Only in adr-1 Mutants Are in Genes with Editing Sites in Wild-Type Worms.

(A) A bar graph representing nucleotide changes found in wild-type and adr-1 mutant worms at the L4 and embryo developmental stages. Also presented are nucleotide changes that were found in adr-1 mutants but not in wild-type worms.

(B–D) Venn diagrams presenting the intersection between genes with editing sites that were detected in adr-1 mutants and not in wild-type worms and

(B) Genes edited in wild-type worms at the embryo or L4 developmental stages.

(C) Genes with their expression upregulated or downregulated at the embryo stage in adr-1 mutants.

(D) Genes with their expression upregulated or downregulated at the L4 stage in adr-1 mutants.

See Table S3.

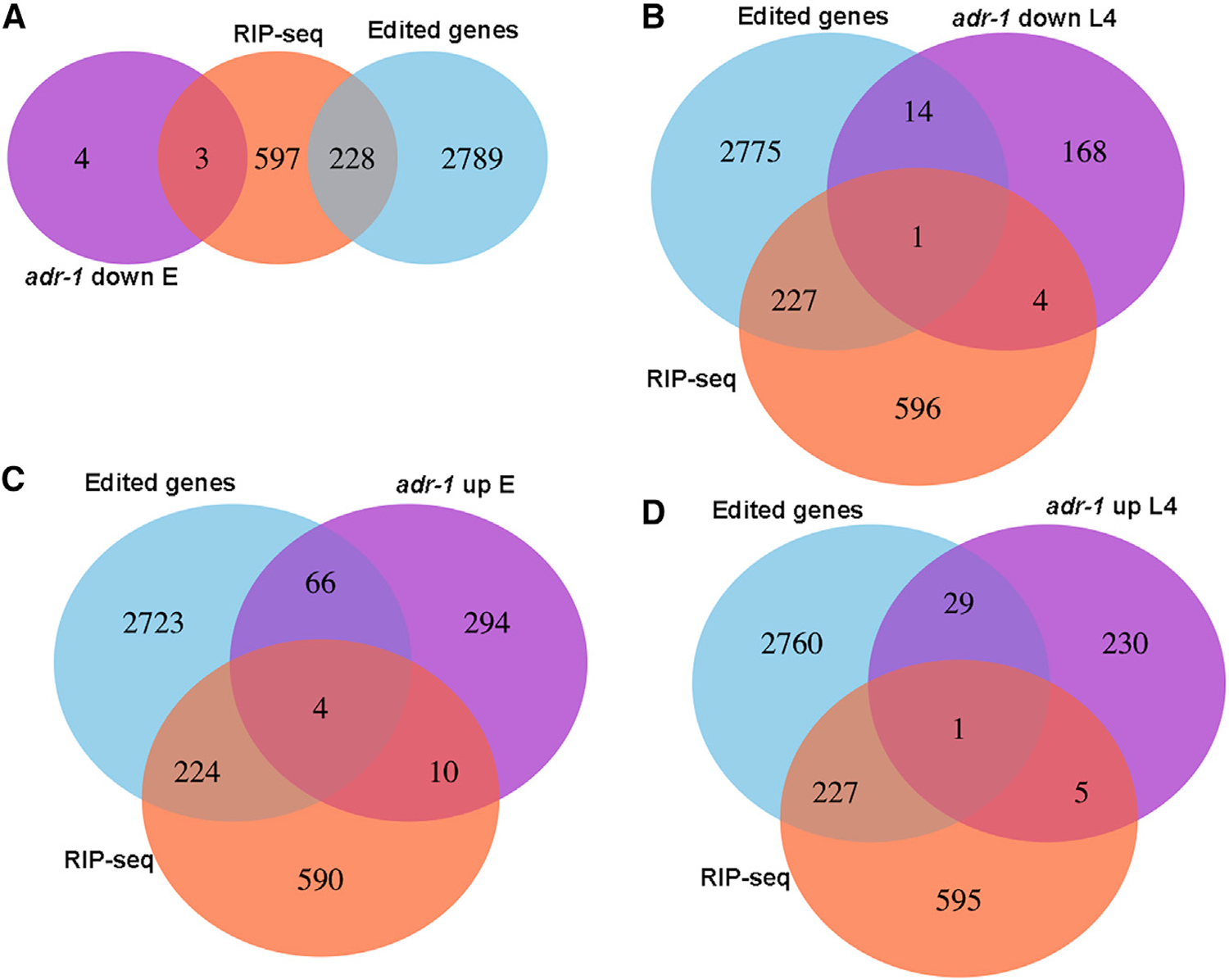

ADR-1 Binds Edited Genes

To study whether ADR-1 affects the expression of genes by binding their RNA, we performed an RNA immunoprecipitation assay on young adult worms using the FLAG antibody and worms expressing the FLAG-1:ADR-1 transgene or worms lacking adr-1 as a negative control. The bound RNAs were extracted, and poly(A) was selected and sequenced by high-throughput sequencing (RIP-seq; Table S4). Almost one-third of the 3′ UTR-edited genes are bound by ADR-1 (Figure S5), and a significant portion of edited genes, in general, as determined by the hypergeometric distribution test (p < e—44; Figure 7). These results confirm that ADR-1 regulates edited genes by binding their RNA either directly or through a common, interacting RNA-binding protein. Interestingly, we found that ADR-1 binds unc-22, which has an important role in the regulation of the actomyosin dynamics (Benian et al., 1989), and unc-54, which encodes a muscle myosin class II heavy chain (Waterston, 1989). Mutations in unc-54 can suppress the twitching phenotype of unc-22, which suggests an interaction between those genes (Moerman et al., 1982). Thus, the new bag of worms phenotype that we observed when adr-1 mutant worms were subjected to unc-22 RNAi (Figure 3B) suggests a function for ADR-1 in muscle formation. This function is probably distinct from the function of ADR-1 in RNA editing because we did not find editing in unc-54 RNA, and unc-22 only has one editing site in an intron. In addition, this phenotype is not as significant in adr-2 mutants.

Figure 7. ADR-1 Binds Edited Genes.

Venn diagrams presenting the intersections between edited genes, genes identified as bound by ADR-1 using RIP-seq analysis and

(A) Genes that their expression is downregulated at embryo stage in adr-1 mutants.

(B) Genes that their expression is downregulated at L4 stage in adr-1 mutants.

(C) Genes that are upregulated at the embryo stage in adr-1 mutants.

(D) Genes that are upregulated at the L4 stage in adr-1 mutants.

RNA Editing Does Not Affect the Protein Levels of Edited Genes

To study whether the changes in RNA levels of genes in ADAR mutants affect their protein levels as well, we performed a comparison between the proteome content of wild-type worms and adr-1- or adr-2-mutant worms at the embryo or L4 developmental stages (Table S5). We extracted proteins from three biological replicates of each strain, trypsinized the proteins, and quantified them by mass spectrometry (see STAR Methods). These experiments identified 5,984 proteins in total; 1,426 were only identified in the embryonic samples, and 1,333 were specific to the L4 stage. Although there was a significant representation of edited genes in the proteomics analysis (Figure S6; p < e—4 for all groups of edited genes), the protein levels of only 22 genes were significantly changed in ADAR mutants (Table S5). Of the 22 genes in which protein levels changed in both adr-1 mutant strains or in both adr-2 mutants strains (not including ADAR genes themselves), four genes were also found to be edited, C06A5.6, W07G4.3, Y54E2A.4, and alh-7. These results are not surprising because most of the editing sites are in non-coding regions (Goldstein et al., 2017), and many of the edited genes in human and C. elegans as well are probably not protein-coding genes. Interestingly, alh-7, which undergoes editing at its 3′ UTR and is a highly conserved neuronal gene (Morse et al., 2002), was significantly downregulated in adr-1 mutants both at the RNA level and the protein level at the embryo stage (Figure 4). Another interesting gene is adbp-1, which is a regulator of adr-2 (Ohta et al., 2008). ADBP-1 was shown to interact with ADR-2 and facilitate its cellular localization (Ohta et al., 2008). We found that the protein level of adbp-1 was significantly downregulated in both adr-2 mutants but not the mRNA levels (Figure 4; Tables S2 and S4), whereas ADR-2 protein was also significantly downregulated in the adbp-1 mutant (Figure S7). These results suggest that the regulation between ADR-2 and ADBP-1 is not unidirectional but that both proteins regulate each other’s stability.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we performed a comprehensive phenotypic, transcriptomics, and proteomics analysis on the two ADAR genes in C. elegans to explore their individual role in the RNA-editing process. We confirmed that ADR-2 is the only active enzyme but found that ADR-1 regulates not only the editing process but also the expression of edited genes. This comprehensive analysis was performed on two different deletion alleles for each ADAR gene to rigorously identify the effects of each ADAR and to avoid allele-specific bias.

ADR-1 Has Distinct Phenotypes and Likely Distinct Functions from ADR-2

The analysis revealed several interesting abnormal phenotypes, some of which are specific to adr-1 mutants. The aberrant chemotaxis phenotype that was previously described (Tonkin et al., 2002) was apparent in all ADAR mutants (Figure S2) and was rescued by an ADR-1 transgene. The expression of the edited gene clec-41 in neuronal cells was shown to be important for that phenotype (Deffit et al., 2017). This suggests that the absence or changes in the levels of editing in specific genes causes the aberrant chemotaxis phenotype. The decrease in the life span was previously observed in worms harboring mutations in either adr-1 or adr-2 genes or both (Sebastiani et al., 2009). When we examined life span of worms harboring the single mutants, we found that the two ADAR genes contribute to the life span of the worms in the opposite direction. The changes in editing levels in ADAR mutants might produce these phenotypes. One possibility is that, when editing is absent in adr-2 mutants, the worms live longer, and when editing levels are reduced or even elevated in specific genes in adr-1 mutants, it causes a reduction in life span. As a decrease in the life span is a very common phenotype in C. elegans, and reduced expression of many edited genes may cause a similar phenotype (Goldstein et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2015), it is hard to pinpoint a particular gene that underlies this phenotype. We only observed a partial rescue of the life span decrease by expressing transgenic adr-1, probably because of insufficient expression of the transgene in the germline and early embryonic cells because the transgene is expressed from an extra-chromosomal array that limits expression in the germline. This may also be the reason why transgenic ADR-1 with mutations in the dsRNA-binding domains rescues to the same degree as the wild-type transgenic ADR-1. It is also possible that the different life-span phenotypes in adr-1 and adr-2 are a result of distinct functions of these genes, which might not be related to RNA editing of one specific gene.

The pvl phenotype seems to be specific to adr-1 mutants, as suggested before (Tonkin et al., 2002), although in a very low penetrance. This phenotype was not allele specific because we observed it in two different alleles and we could partially rescue this phenotype with adr-1 transgenes. Another phenotype that seems to be specific to adr-1 mutants is the bag of worms (BOW) phenotypes when the mutant worms are subjected to unc-22 RNAi. Both phenotypes, pvl and BOW, are probably related to each other. adr-1, unc-22, and unc-54 are expressed in the vulva (Moerman et al., 1988; Tonkin et al., 2002) and bind to each other. Because unc-22 and unc-54 do not appear to be regulated by RNA editing, these phenotypes are probably not related to RNA editing and possibly ADR-1 has other functions not related to RNA editing, including regulating vulva formation.

In general, adr-1 mutant phenotypes are more severe than adr-2 phenotypes, and the double-mutant phenotypes seem to be the middle ground between the phenotypes of the two single mutations for most phenotypes. Thus, it is likely that changes in the editing levels are more harmful than a complete loss of editing.

RNA Editing Process Is Highly Regulated

Our results show that ADR-1 has a significant effect on edited genes. We found that there is a decrease in the overall expression level of genes edited within 3′UTRs, that ADR-1 binds edited genes, and that a significant portion of upregulated genes in adr-1 mutants are genes edited at the L4 stage. Moreover, we found that the effect of ADR-1 on editing is stronger at the L4 developmental stage than it is at the embryo stage. Thus, ADR-1 can both upregulate and downregulate the expression of edited genes, and that might depend on the level of editing in a specific gene or even a specific site within a gene.

ADR-1 does not have deamination activity and was suggested to regulate editing by binding to ADR-2 targets and facilitating or preventing ADR-2 activity (Washburn et al., 2014). Indeed, we observed that a very significant portion of ADR-1 binding targets are edited genes. The RIP-seq experiments that we performed do not exclude indirect binding to edited genes; however, the RNA binding domains in the ADR-1 protein were shown to have an important role in editing regulation (Rajendren et al., 2018; Washburn et al., 2014). When we used a mutated version of ADR-1-FLAG with mutations in the RNA-binding domain, the rescue of the vulva and life-span phenotypes was similar to that of the strain expressing the wild-type ADR-1-FLAG transgene. Although Washburn et al. (2014) demonstrated that ADR-1 with mutations in both dsRNA-binding domains cannot bind several edited genes by RIP experiments coupled to qPCR, it is possible that the mutated ADR-1 lacks the ability to bind ADR-2 targets but can bind other mRNAs. Another hypothesis is that some of adr-1 mutant phenotypes are not related to the ADR-1 function in editing. Therefore, it is possible that the RNA-binding domains are needed for ADR-1 function in editing, and the inactive deamination domain has evolved to perform other ADR-1 functions, such as in muscle formation.

By detecting edited sites that occur only in adr-1 mutants, we found that the effect of ADR-1 on editing is more significant at the L4 developmental stage than it is in the embryo stage. This result goes well together with our findings that the expression of several edited genes is also upregulated in adr-1 mutant worms (Figure 5) and that the phenotypes observed in adr-1 mutants are associated with more-advanced stages of development. These results suggest that the main function of ADR-1 is regulating editing by ADR-2 at the L4 stage. We found that most of the editing sites that are unique to adr-1 mutants at the embryo stage are in genes that undergo editing at other sites in wild-type worms. It is possible that these sites were not detected in wild-type worms because of the restriction of at least 5% editing in the analysis. It was shown that ADR-1 can both enhance and reduce the levels of editing (Washburn et al., 2014); therefore, these sites might appear only in adr-1 mutants because their editing level was enhanced enough to cross the threshold. This, together with the absence of unique editing sites in the adr-1 mutants leading to altered gene regulation, indicates that ADR-1 primarily promotes editing and does not prevent ADR-2 binding to specific sites and editing to result in altered gene expression.

Not many regulators of RNA editing are known in C. elegans. Only one protein, other than ADR-1, was also shown to regulate editing. That protein, ADBP-1 (ADR-2 binding protein-1), was previously shown to alter ADR-2 nuclear localization (Ohta et al., 2008). We found that both ADR-2 and ADBP-1 regulate each other’s protein levels. It is not clear how ADR-2 affects ADBP-1; however, it seems to be affected at the protein level because the RNA expression of adbp-1 is not affected in adr-2 mutants. Other editing regulators might also be involved, regulating editing in a developmental-specific, tissue-specific, and cellular-specific manner (Ganem and Lamm, 2017).

The Major Role of RNA Editing Is to Regulate RNA Levels and Not Protein levels

In our previous study (Goldstein et al., 2017), we found that the level of expression in genes edited at their 3′ UTR is slightly, but significantly, less in worms mutated in adr-1 and adr-2, compared with wild-type worms. In this study, we also observed that reduction in gene expression in the single-ADAR mutants at the embryo stage. Hundreds of genes were 2-fold upregulated and downregulated at the RNA level in the single-ADAR mutants, and there was a significant portion of L4-edited genes in adr-1 upregulated genes. However, only 22 genes had a significant change in protein levels in adr-1 or adr-2 mutant worms. From them, only four genes were found to be edited (Goldstein et al., 2017), even though there was a high representation of edited genes in the proteomics data. Recently, RNA editing was shown to have an important part in suppressing the innate immune response in mammals (George et al., 2016; Liddicoat et al., 2015; Mannion et al., 2014) by marking self-produced dsRNA, which prevented endogenous dsRNA from triggering the immune response. It is possible that RNA editing has a similar function in C. elegans, e.g., marking self-dsRNA to prevent the immune response (RNAi) from processing and degrading the RNA (Reich et al., 2018; Ganem and Lamm, 2017). In addition, most of the edited sites in mammals and in C. elegans are in non-coding regions (for example, pseudogenes, intergenic regions, and transposons) (Athanasiadis et al., 2004; Barak et al., 2009; Blow et al., 2004; Goldstein et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2004; Levanon et al., 2004; Li et al., 2009b; Warf et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2011). Thus, probably the main function of RNA editing in C. elegans is not to alter the content of the proteins in the cell but rather to buffer other processes, such as RNAi.

STAR★METHODS

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for reagents may be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Ayelet Lamm (ayeletla@technion.ac.il).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAIL

Maintenance and handling of C. elegans strains

Worm strains are described in the Key Resources Table. All strains were grown at 20°C on NGM agar media with OP50 as food as described in Brenner (1974). The genotype of each of the strains was validated by PCR and sequencing before use. Embryos were isolated from adult worms by washing worms with M9 and sodium hypochloride. To collect L4 worms, embryos were left overnight in M9 in a nutator at 20°C and the hatched synchronized L1 larva were placed on NGM agar plate until they reached the L4 larva stage. L4 developmental stage was confirmed using binocular, by measuring ~650 µm in length. Embryos or L4 larva worms were resuspended in either M9 for proteomic analysis or EN buffer for RNA extraction and frozen into pellets with liquid nitrogen. Only fluorescent worms were counted for every experiment that used strains HH76, HH116, and HH134.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Custom ADR-2 antibody | Deffit et al., 2017 | N/A |

| Custom ADR-1 antibody | Washburn et al., 2014 | N/A |

| β-actin antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | N/A |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| Escherichia coli OP50 | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC) | N/A |

| Escherichia coli HT115 | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC) | N/A |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| IPTG | ORNAT INA | Cat# INA-1758-1400 |

| Ampicillin sodium salt | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# A9518-25G |

| 5-Fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine (FUDR) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# F0503-100MG |

| Trizol | Invitrogen | Cat# 15596026 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| SMARTer® Stranded RNA-Seq Kit | Clontech Laboratories | Cat# 634836 |

| Ribozero kit | Epicenter | Cat# MRZH116 |

| mirVana | Ambion | Cat#AM1560 |

| DNase I | Ambion | Cat# AM2222 |

| DNase | Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH | N/A |

| Phire Tissue Direct PCR Master Mix | Thermo Scientific | Cat#F170S |

| RNeasy Extraction Kit | QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany | N/A |

| SuperScriptIII | Invitrogen | Cat# 18080093 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Raw and analyzed data | This paper | GEO: GSE110701 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| C. elegans: Strain Bristol N2 | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | Tonkin et al., 2002 |

| C. elegans: Strain BB2: adr-1 (gv6) I | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | Tonkin et al., 2002 |

| C. elegans: Strain BB3: adr-2 (gv42) III | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | Tonkin et al., 2002 |

| C. elegans: Strain BB4: adr-1 (gv6) I; adr-2 (gv42) III | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | Tonkin et al., 2002 |

| C. elegans: Strain BB19: adr-1 (tm668) I | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | Hundley et al., 2008 |

| C. elegans: Strain RB886: adr-2 (ok735) III | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | Hundley et al., 2008 |

| C. elegans: Strain BB21: adr-1 (tm668) I; adr-2 (ok735) III | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | Hundley et al., 2008 |

| C. elegans: Strain QD1: adbp-1(qj1) II | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | Ohta et al., 2008 |

| C. elegans: Strain HH76: adr-1(tm668) I blmEx1[3XFLAG-adr-1 genomic, rab3::gfp::unc-54] | Washburn et al., 2014 | |

| C. elegans: Strain HH116: adr-1(tm668) I blmEx1[3XFLAG-adr-1 genomic with mutations in dsRBD1 (K223E, K224A, and K227A) and dsRBD2 (K583E, K584A and K587A), rab3::gfp::unc-54] | Washburn et al., 2014 | |

| C. elegans: Strain HH134: adr-1(tm668);adr-2(ok735) I blmEx1[3XFLAG-adr-1 genomic, rab3::gfp::unc-54] | Washburn et al., 2014 | |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| F48E8.4 Forward 5′ - CTTCTAGTCCCGCCAAATTTATG - 3′ | This study | N/A |

| F48E8.4 Reverse 5′ – CAGTTGAAGTTATTCCACGACCC - 3′ | This study | N/A |

| rncs-1 Forward 5′ – ATTTTTTCCCGACAAAGATGGAACTC AAGGAT – 3′ | This study | N/A |

| rncs-1 Reverse 5′ – TGATTCAACATTTCAAAAACTTGTATTTTACATCTAAAACTATAAA – 3′ | This study | N/A |

| AL_SD_1 adr-1(gv6) forward: CAATGTCGCAAAACCAAATG | This study | N/A |

| AL_OBN_132 adr-1(gv6) reverse: GAGATGTTCCATTGGCTCC | This study | N/A |

| AL_SD_3 adr-2(gv42) forward: AAGGAAAGAACGCATTGGTG | This study | N/A |

| AL_SD_4 adr-2(gv42) reverse: GTTTCTCAGCTCCAGGCATC | This study | N/A |

| AL_SD_7 adr-1(tm668) forward: CCAGGGTTGGATCCTCTCGGTG | This study | N/A |

| AL_SD_8 adr-1(tm668) reverse: GTCACGAAGAGCTTCACGAATGACC | This study | N/A |

| AL_SD_6 adr-2(ok735) forward: AGCCTGAGCTCG CTTCCAATCTTCAAG | This study | N/A |

| AL_SD_5 adr-2(ok735) reverse: CCCCCAGCTTACAGT AATCATCAGTTCTGCC | This study | N/A |

| HH1944:GTAATTTATTTGACTACGAAATGGATC | This study | N/A |

| HH1945:TCCAATTTGGTTTGTTTTGG | This study | N/A |

| HH1948:CTCTCGGCATATTTCCTCTATATTG | This study | N/A |

| HH1949: TGTCCATAACCGAAGTTGTAGTTAG | This study | N/A |

| HH1952: AGGTAATTTATTTGACTACGAAATGGATC | This study | N/A |

| HH1953:TTATTTTGCGAAATTGTTGTTACG | This study | N/A |

| HH1954: CGACTCCATCCAGATTGTG | This study | N/A |

| HH1955:GTTTCCTTAAATAATATTCAACTCCG | This study | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Plasmid:unc-22 (RNAi) | Kamath et al., 2001 | N/A |

| Plasmid:lin-1 (RNAi) | Kamath et al., 2001 | N/A |

| Plasmid: L4440 | Fire lab C. elegans Vector Kit 1995, Addgene | Addgene: #1654 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Bowtie | Langmead et al., 2009 | http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/index.shtml |

| DESeq package in R | Anders and Huber, 2010 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq.html |

| Samtools | Li et al., 2009a | http://samtools.sourceforge.net/ |

| MaxQuant 1.5.2.8 | (Cox and Mann, 2008; version 1.5.2.8) | N/A |

| LC-MS/MS on Q Exactive plus | Thermo | N/A |

METHOD DETAILS

Lifespan assay

Synchronized L1 worms were plated and kept at 15°C, until they reached L4 stage (after about 48 hours). L4 worms from each tested strain were transferred to 5 FUdR plates, about 50 worms per plate. FUdR was added to the NGM agar before pouring the plates, to a final concentration of 4.95 µM, in order to prevent the worms from having progeny. Live and dead worms were counted every 2–4 days. A worm was considered dead when it did not respond to touch of the platinum wire pick, and was subsequently removed from the plate. Worms that crawled over the edges of the plates and dried out were reduced from the total count. At least three biological replicates were performed for each experiment.

Assays for Bag of worms Phenotype, vulva abnormalities, and hypersensitivity in worms

To perform RNAi, unc-22 (Kamath et al., 2001) or lin-1 (Kamath et al., 2003) or empty L4440 plasmids were transformed into E. coli HT115 bacteria and were cultured overnight at 37°C in LB media containing 100 µg/ml ampicillin. The cultured bacteria were seeded onto C. elegans growth media plates (NGM) containing 100 µg/ml ampicillin and 10 µg/ml IPTG and incubated overnight at RT overnight. Synchronized embryos were placed on the plates and incubated for 72–96 hours at 20°C before scoring. Worms were then scored using Nikon SMZ745 zoom stereomicroscope for PVL, BOW, or Multivulva phenotype. Worms presenting the phenotypes were counted in relative to the total number of worm in each plate. In the RNAi experiments the fraction of worms presenting the phenotype in the empty vector experiment was subtracted from the fraction of worms presenting the phenotype in the unc-22 or lin-1 RNAi experiments.

DNA and RNA Sanger sequencing

To obtain cDNA, extracted RNA (MirVana) was treated with DNase I (Ambion) and then a reverse transcriptase reaction was performed with SuperScriptIII (Invitrogen), using 6-mer random primers. DNA was extracted using Phire Tissue Direct PCR Master Mix (Thermo Scientific). The amplification products were directly sequenced by Sanger sequencing.

Isoforms validation

Presence of ADR-1 isoforms in different worm strains was assessed via PCR amplification of cDNA from adult worms of strains N2, adr-1(gv6), adr-2(gv42), adr-1(gv6);adr-2(gv42), adr-1(tm668), adr-2(ok735), and adr-1(tm668); adr-2(ok735). RNA was isolated from whole worms using Trizol (Invitrogen) followed by DNase (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH) treatment, and purification using the RNeasy Extraction Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). cDNA was synthesized from 2ug of whole worm RNA using Superscript III(Invitrogen) along with random hexamers (Fisher Scientific) and oligo-dT (Fisher Scientific) primers. Amplification of the different isoforms was carried out using Platinum PFX DNA Polymerase and 3ul of cDNA from each strain. ADR-1 isoform C was amplified using primers HH1944 and HH1945. ADR-1 isoform E was amplified using primers HH1948 and HH1949. ADR-1 isoform G was amplified using primers HH1952 and HH1953. ADR-2 was amplified using primers HH1954 and HH1955.

Chemotaxis Assay

Adult worms were used to assess chemotaxis behavior similarly to what was performed in Deffit et al. (2017). Chemotaxis to benzaldehyde (1:1000 dilution in ethanol) and trimethylthiazole (1:10,000 dilution) was assessed and chemotaxis index determined using the formula in Deffit et al. (2017). Three replicate plates for each worm strain were used in each of the 5–9 biological replicates.

Western analysis

Plates of starved worms were chunked onto 15 cm plates and allowed to grow for 3 days, with additional food added at day 2 to prevent starvation. Worms were collected from NGM plates using 1X M9 buffer (0.04 M Na2HPO4, 0.02 M KH2PO4, 0.009 M NH4Cl, 0.02 M NaCl), washed with extract buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.4]; 70 mM K-Acetate, 5 mM Mg-Acetate, 0.05% NP-40, and 10% glycerol) and frozen at —80°C. A cold motor and pestle were used to make worm lysates from the frozen pellets. The total protein concentration of the lysates was quantified using a Bradford assay (Sigma-Aldrich) and an equivalent amount of lysates from each strain were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with a custom ADR-2 antibody (described in Deffit et al., 2017) and an antibody to β-actin (Cell Signaling Technology).

mRNA-seq libraries preparation

Embryos and L4 worms frozen pellets were grounded to powder with a liquid nitrogen chilled mortar and pestle. RNA in high and low molecular weight fractions was extracted by mirVana kit (Ambion). RNA sequencing libraries were prepared from the high molecular weight fraction using the SMARTer® Stranded RNA-Seq Kit (Clontech Laboratories) after ribosomal depletion by Ribozero kit (Epicenter) and sequenced with an Illumina HiSeq 2500.

Proteomics

50µl of frozen pellets from three biological replicates of each strain in embryo or L4 stage were taken for the proteomics analysis. Proteins from the different samples were extracted by using urea buffer containing: 9M Urea, 400mM Ammonium bicarbonate [ABC] and 10mM DTT in the ratio of 600ul buffer to 50ul sample. The samples were then sonicated on ice (7’, 10 s on/off pulse, 90% duty) and vortexed roughly. This procedure was repeated twice. The samples were then centrifuged at 14000rpm for 10’ and 17000 g for 10’ in order to sediment the residual cuticle debris. Then the extracted proteins were trypsinized, and analyzed by LC-MS/MS on Q Exactive plus (Thermo).

RIP-seq

Using worm strains containing a FLAG-ADR-1 transgene and lacking endogenous adr-1 (HH76) or lacking both endogenous adr-1 and adr-2 (HH134) and adr-1(−) (BB21) worms as a negative control, the ADR-1 RNA immunoprecipitation was performed as previously described (Washburn et al., 2014). For two biological replicates of each RIP experiment, RNA extracted from portion of the input lysates and the immunoprecipitated RNA were subjected polyA selection using magnetic oligo-dt beads (Ambion) and a KAPA Stranded RNA-seq Library Preparation Kit (KAPA Biosystems). Equivalent amounts of the libraries were subjected to high-throughput sequencing on an Illumina NextSeq500 at the IU-Center for Genomics and Bioinformatics.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

RNA editing sites and gene expression analysis

To extend the list of 3′UTR edited genes, non-repetitive edited sites found by Goldstein et al. (2017) were reannotated according to the newest Wormbase (WS261). A gene was added to the list of 3′UTR edited genes if according to the new annotation it has multiple editing sites in its 3′UTR at the same orientation of the gene or multiple edited sites were found in proximity to the 3′UTR of the gene, less than 200bp apart, at the same orientation of the gene. At least three different biological RNA-seq samples were generated from N2 and ADAR mutant worms (BB2, BB19, BB3 and RB886), each at embryo and L4 stage. All reads were trimmed to 47nt and identical reads were merged. Sequences were aligned to gene transcripts from WS220 (Wormbase, www.wormbase.org) using Bowtie (Langmead et al., 2009). DESeq (Anders and Huber, 2010) package in R was used to identify differentially expressed genes. Significantly differently regulated genes were genes with at least 2-fold change in expression, with p-adj value ≤ 0.05. P values for expression differences between 3′UTR edited genes and all genes were calculated by Welch two-sample t test only for genes with p-adj value < 0.05. P value for each mutant was calculated independently of other mutants. The Venn diagram overlap p value was calculated by hypergeometric distribution using Phyper function in R. Identification of editing sites in adr-1 mutants was done essentially as described in (Goldstein et al., 2017). The main difference is an increased stringency that a nucleotide change was selected only if it appeared in both adr-1 mutants. In short, sequences from both adr-1 mutants were aligned to WS220 genome using Bowtie (Langmead et al., 2009) with the restriction of not more than two alignments to exclude repetitive regions and were clustered using Samtools (Li et al., 2009a). Nucleotide change were selected if they appeared in both adr-1 mutants, with at least 5% reads aligned to the site that contain the change and not more than 1% of reads with other nucleotide changes. Nucleotide changes were removed if they appeared in DNA-sequences or in RNA sequences from worms mutated in both ADAR genes, adr-1 and adr-2 (BB21 and BB4 strains).

Proteomics analysis

The proteomics data was analyzed with MaxQuant 1.5.2.8 (Cox and Mann, 2008) versus the Caenorhabditis elegans part of the Uniprot database. Each mutant’s sample data was analyzed against the WT (N2) sample and known contaminants were removed. Only proteins that were identified with at least 2 peptides were tested for significant differences. Student t test p value threshold on LFQ intensities was set to 0.05. Difference threshold on LFQ intensities was set to ± 0.8.

RIP-seq analysis

The RIP-seq 75 bp SE raw reads were trimmed of sequencing adapters, polyA tails, and repetitive elements using cutadapt (v1.9.1), and aligned with STAR (v2.4.0i) against RepBase (v18) to remove repetitive elements. Reads were then aligned to ce10 using the following STAR parameters: [outFilterMultimapNmax 10, outFilterScoreMinOverLread: 0.66, outFilterMatchN-minOverLread: 0.66, outFilterMismatchNmax: 10, outFilterMismatchNoverLmax: 0.3]. Read sorting and indexing was performed using Samtools 1.3.1. Gene expression was quantified with featureCounts (v1.5.0) using reads that map to exons. Raw read counts were input into DESeq2 (v1.18.1) to quantify differential expression for each IP/input pair using three replicates for the input samples and two replicates for the IP per condition. One IP replicate clustered independently by batch rather than genotype and therefore was removed from the final analysis. Genes enriched in IP were selected with a BH corrected p value less than 0.05 and a log2 fold change greater than 0.5. Genes that are enriched in both ADR-1 samples (FLAG-ADR-1 in adr-1(−) and FLAG-ADR-1 in adr-1(−);adr-2(−)) and not in the negative control sample (adr-1(−)) were called as ADR-1 bound targets.

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

The sequence data from this study have been submitted to the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession number GSE110701.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Changes in RNA editing levels are harmful to normal development

In C. elegans, editing affects genes at the RNA level, but not at the protein level

ADR-1 function is to promote editing by ADR-2 at the L4 larval stage

C. elegans ADR-1 has developmental functions that are unrelated to RNA editing

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the reviewers for their suggestions, which helped improve the manuscript. We thank Smoler proteomics center at the Technion for help with the proteomics analysis. Some strains were provided by the CGC, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440). This work was funded by The Israeli Centers of Research Excellence (I-CORE) program (center 1796/12 to A.T.L.), the Israel Science Foundation (grants 644/13, 927/18, and 2154/16 to A.T.L.), the Binational Israel-USA Science Foundation (grant 2015091 to A.T.L. and H.A.H.), the NIH (F32GM119257-01A1 to S.N.D.), and the American Cancer Society (RSG-15-051 RMC to H.A.H.).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2019.03.095.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- Anders S, and Huber W (2010). Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol 11, R106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athanasiadis A, Rich A, and Maas S (2004). Widespread A-to-I RNA editing of Alu-containing mRNAs in the human transcriptome. PLoS Biol 2, e391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak M, Levanon EY, Eisenberg E, Paz N, Rechavi G, Church GM, and Mehr R (2009). Evidence for large diversity in the human transcriptome created by Alu RNA editing. Nucleic Acids Res 37, 6905–6915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass BL (2006). How does RNA editing affect dsRNA-mediated gene silencing? Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol 71, 285–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benian GM, Kiff JE, Neckelmann N, Moerman DG, and Waterston RH (1989). Sequence of an unusually large protein implicated in regulation of myosin activity in C. elegans. Nature 342, 45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blow M, Futreal PA, Wooster R, and Stratton MR (2004). A survey of RNA editing in human brain. Genome Res 14, 2379–2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S (1974). The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77, 71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns CM, Chu H, Rueter SM, Hutchinson LK, Canton H, Sanders-Bush E, and Emeson RB (1997). Regulation of serotonin-2C receptor G-protein coupling by RNA editing. Nature 387, 303–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J, and Mann M (2008). MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol 26, 1367–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deffit SN, Yee BA, Manning AC, Rajendren S, Vadlamani P, Wheeler EC, Domissy A, Washburn MC, Yeo GW, and Hundley HA (2017). The C. elegans neural editome reveals an ADAR target mRNA required for proper chemotaxis. eLife 6, e28625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganem NS, and Lamm AT (2017). A-to-I RNA editing—thinking beyond the single nucleotide. RNA Biol 14, 1690–1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George CX, Ramaswami G, Li JB, and Samuel CE (2016). Editing of cellular self-RNAs by adenosine deaminase ADAR1 suppresses innate immune stress responses. J. Biol. Chem 291, 6158–6168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein B, Agranat-Tamir L, Light D, Ben-Naim Zgayer O, Fishman A, and Lamm AT (2017). A-to-I RNA editing promotes developmental stage-specific gene and lncRNA expression. Genome Res 27, 462–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi M, Maas S, Single FN, Hartner J, Rozov A, Burnashev N, Feldmeyer D, Sprengel R, and Seeburg PH (2000). Point mutation in an AMPA receptor gene rescues lethality in mice deficient in the RNA-editing enzyme ADAR2. Nature 406, 78–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hundley HA, Krauchuk AA, and Bass BL (2008). C. elegans and H. sapiens mRNAs with edited 3’ UTRs are present on polysomes. RNA 14, 2050–2060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath RS, Martinez-Campos M, Zipperlen P, Fraser AG, and Ahringer J (2001). Effectiveness of specific RNA-mediated interference through ingested double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genome Biol 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath RS, Fraser AG, Dong Y, Poulin G, Durbin R, Gotta M, Kanapin A, Le Bot N, Moreno S, Sohrmann M, et al. (2003). Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature 421, 231–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DD, Kim TT, Walsh T, Kobayashi Y, Matise TC, Buyske S, and Gabriel A (2004). Widespread RNA editing of embedded alu elements in the human transcriptome. Genome Res 14, 1719–1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight SW, and Bass BL (2002). The role of RNA editing by ADARs in RNAi. Mol. Cell 10, 809–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, and Salzberg SL (2009). Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol 10, R25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levanon EY, Eisenberg E, Yelin R, Nemzer S, Hallegger M, Shemesh R, Fligelman ZY, Shoshan A, Pollock SR, Sztybel D, et al. (2004). Systematic identification of abundant A-to-I editing sites in the human transcriptome. Nat. Biotechnol 22, 1001–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, and Durbin R; 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup (2009a). The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JB, Levanon EY, Yoon J-K, Aach J, Xie B, Leproust E, Zhang K, Gao Y, and Church GM (2009b). Genome-wide identification of human RNA editing sites by parallel DNA capturing and sequencing. Science 324, 1210–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddicoat BJ, Piskol R, Chalk AM, Ramaswami G, Higuchi M, Hartner JC, Li JB, Seeburg PH, and Walkley CR (2015). RNA editing by ADAR1 prevents MDA5 sensing of endogenous dsRNA as nonself. Science 349, 1115–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannion NM, Greenwood SM, Young R, Cox S, Brindle J, Read D, Nellaker C, Vesely C, Ponting CP, McLaughlin PJ, et al. (2014). The RNA-editing enzyme ADAR1 controls innate immune responses to RNA. Cell Rep 9, 1482–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moerman DG, Plurad S, Waterston RH, and Baillie DL (1982). Mutations in the unc-54 myosin heavy chain gene of Caenorhabditis elegans that alter contractility but not muscle structure. Cell 29, 773–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moerman DG, Benian GM, Barstead RJ, Schriefer LA, and Waterston RH (1988). Identification and intracellular localization of the unc-22 gene product of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev 2, 93–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse DP, and Bass BL (1999). Long RNA hairpins that contain inosine are present in Caenorhabditis elegans poly(A)+ RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 6048–6053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse DP, Aruscavage PJ, and Bass BL (2002). RNA hairpins in noncoding regions of human brain and Caenorhabditis elegans mRNA are edited by adenosine deaminases that act on RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99, 7906–7911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta H, Fujiwara M, Ohshima Y, and Ishihara T (2008). ADBP-1 regulates an ADAR RNA-editing enzyme to antagonize RNA-interference-mediated gene silencing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 180, 785–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palladino MJ, Keegan LP, O’Connell MA, and Reenan RA (2000). A-to-I pre-mRNA editing in Drosophila is primarily involved in adult nervous system function and integrity. Cell 102, 437–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullirsch D, and Jantsch MF (2010). Proteome diversification by adenosine to inosine RNA editing. RNA Biol 7, 205–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajendren S, Manning AC, Al-Awadi H, Yamada K, Takagi Y, and Hundley HA (2018). A protein-protein interaction underlies the molecular basis for substrate recognition by an adenosine-to-inosine RNA-editing enzyme. Nucleic Acids Res 46, 9647–9659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich DP, Tyc KM, and Bass BL (2018). C. elegans ADARs antagonize silencing of cellular dsRNAs by the antiviral RNAi pathway. Genes Dev 32, 271–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai M, Shiromoto Y, Ota H, Song C, Kossenkov AV, Wickramasinghe J, Showe LC, Skordalakes E, Tang H-Y, Speicher DW, and Nishikura K (2017). ADAR1 controls apoptosis of stressed cells by inhibiting Staufen1-mediated mRNA decay. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 24, 534–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastiani P, Montano M, Puca A, Solovieff N, Kojima T, Wang MC, Melista E, Meltzer M, Fischer SEJ, Andersen S, et al. (2009). RNA editing genes associated with extreme old age in humans and with lifespan in C. elegans. PLoS One 4, e8210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmer F, Tijsterman M, Parrish S, Koushika SP, Nonet ML, Fire A, Ahringer J, and Plasterk RHA (2002). Loss of the putative RNA-directed RNA polymerase RRF-3 makes C. elegans hypersensitive to RNAi. Curr. Biol 12, 1317–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon O, Oren S, Safran M, Deshet-Unger N, Akiva P, Jacob-Hirsch J, Cesarkas K, Kabesa R, Amariglio N, Unger R, et al. (2013). Global regulation of alternative splicing by adenosine deaminase acting on RNA (ADAR). RNA 19, 591–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonkin LA, and Bass BL (2003). Mutations in RNAi rescue aberrant chemotaxis of ADAR mutants. Science 302, 1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonkin LA, Saccomanno L, Morse DP, Brodigan T, Krause M, and Bass BL (2002). RNA editing by ADARs is important for normal behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO J 21, 6025–6035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Khillan J, Gadue P, and Nishikura K (2000). Requirement of the RNA editing deaminase ADAR1 gene for embryonic erythropoiesis. Science 290, 1765–1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warf MB, Shepherd BA, Johnson WE, and Bass BL (2012). Effects of ADARs on small RNA processing pathways in C. elegans. Genome Res 22, 1488–1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washburn MC, Kakaradov B, Sundararaman B, Wheeler E, Hoon S, Yeo GW, and Hundley HA (2014). The dsRBP and inactive editor ADR-1 utilizes dsRNA binding to regulate A-to-I RNA editing across the C. elegans transcriptome. Cell Rep 6, 599–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterston RH (1989). The minor myosin heavy chain, mhcA, of Caenorhabditis elegans is necessary for the initiation of thick filament assembly. EMBO J 8, 3429–3436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werry TD, Loiacono R, Sexton PM, and Christopoulos A (2008). RNA editing of the serotonin 5HT2C receptor and its effects on cell signalling, pharmacology and brain function. Pharmacol. Ther 119, 7–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whipple JM, Youssef OA, Aruscavage PJ, Nix DA, Hong C, Johnson WE, and Bass BL (2015). Genome-wide profiling of the C. elegans dsRNAome. RNA 21, 786–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Lamm AT, and Fire AZ (2011). Competition between ADAR and RNAi pathways for an extensive class of RNA targets. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 18, 1094–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H-Q, Zhang P, Gao H, He X, Dou Y, Huang AY, Liu X-M, Ye AY, Dong M-Q, and Wei L (2015). Profiling the RNA editomes of wild-type C. elegans and ADAR mutants. Genome Res 25, 66–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The sequence data from this study have been submitted to the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession number GSE110701.