Abstract

Aims

Our objective was to better understand the genetic bases of dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), a leading cause of systolic heart failure.

Methods and results

We conducted the largest genome-wide association study performed so far in DCM, with 2719 cases and 4440 controls in the discovery population. We identified and replicated two new DCM-associated loci on chromosome 3p25.1 [lead single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs62232870, P = 8.7 × 10−11 and 7.7 × 10−4 in the discovery and replication steps, respectively] and chromosome 22q11.23 (lead SNP rs7284877, P = 3.3 × 10−8 and 1.4 × 10−3 in the discovery and replication steps, respectively), while confirming two previously identified DCM loci on chromosomes 10 and 1, BAG3 and HSPB7. A genetic risk score constructed from the number of risk alleles at these four DCM loci revealed a 3-fold increased risk of DCM for individuals with 8 risk alleles compared to individuals with 5 risk alleles (median of the referral population). In silico annotation and functional 4C-sequencing analyses on iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes identify SLC6A6 as the most likely DCM gene at the 3p25.1 locus. This gene encodes a taurine transporter whose involvement in myocardial dysfunction and DCM is supported by numerous observations in humans and animals. At the 22q11.23 locus, in silico and data mining annotations, and to a lesser extent functional analysis, strongly suggest SMARCB1 as the candidate culprit gene.

Conclusion

This study provides a better understanding of the genetic architecture of DCM and sheds light on novel biological pathways underlying heart failure.

Keywords: Dilated cardiomyopathy, Heart failure, GWAS, Imputation, 4C-sequencing, Genetic risk score

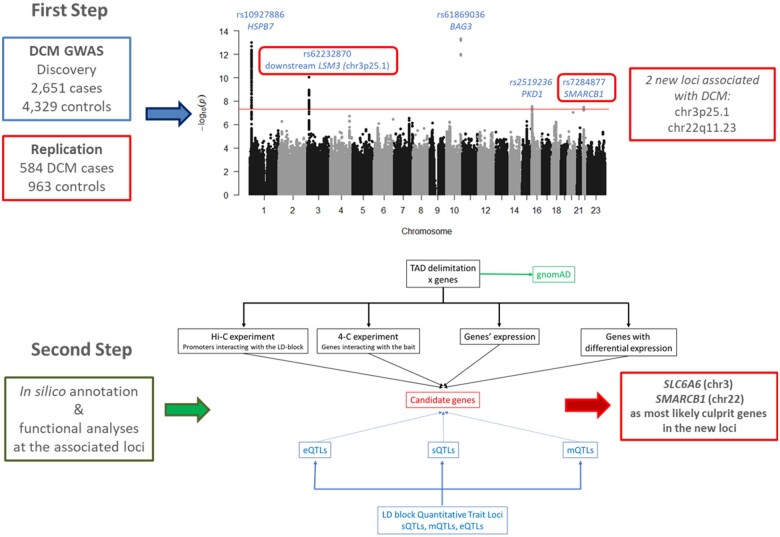

Graphical Abstract

Step 1: Through the largest genome-wide association study performed so far in dilated cardiomyopathy, we identified and replicated two new loci on chromosome 3p25.1 and 22q11.23. Step 2: Combined in silico and functional analyses at the associated loci revealed the best culprit gene at each locus: SLC6A6 (chromosome 3) and SMARCB1 (chromosome 22). The discovery of these two new players shed light on novel biological pathways and putative new therapeutic targets.

See page 2012 for the editorial comment on this article (doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab172)

Introduction

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a heart muscle disease characterized by left ventricular dilatation and systolic dysfunction in the absence of abnormal loading conditions or coronary artery disease.1 , 2 It is a major cause of systolic heart failure, the leading indication for heart transplantation, and therefore a major public health problem due to the important cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.1 , 2 Understanding of the genetic basis of DCM has improved in recent years with a role for both rare and common variants resulting in a complex genetic architecture of the disease.3 , 4 More than 50 genes5 with rare pathogenic mutations have been reported as causing DCM, mainly inherited as dominant with variable penetrance. Several large-scale association studies in sporadic cases have been performed to identify common DCM-associated alleles including several genome-wide association studies (GWAS).3 , 6 , 7 Altogether, these genetic investigations have so far robustly identified two loci presenting common susceptibility alleles: a locus on chromosome 1, encompassing multiple candidate genes in high linkage disequilibrium (LD), including ZBZTB17/MIZ-1 and HSPB77 , 8; and a second on chromosome 10 whose culprit gene, BAG3, is also involved in familial forms of DCM.7 , 9 An exome-wide association study also suggested the existence of six potential additional DCM loci.7 Here, we report the results of an imputed GWAS for sporadic DCM with main findings replication in two independent case-control cohorts. In silico annotation and functional analyses were performed to identify the best candidate culprit genes at identified loci.

Methods

Population and sample collection

A full description of the studied populations is reported in Supplementary material online, Cohort description; Table S1. Briefly, 2719 sporadic DCM patients and 4440 controls from five populations of European ancestry (France, Germany, USA, Italy, and UK) were included in the discovery GWAS. Two European replication cohorts totalling 584 DCM cases and 963 controls were also available. Sporadic DCM was diagnosed according to standard criteria2 , 4 by reduced ejection fraction and enlarged left ventricular end-diastolic volume/diameter in the absence of any obvious pathology. The study protocol was approved by local ethics committees, complied with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all patients signed informed consent.

Genotyping, genotype calling, and imputation

Descriptions of genotyping arrays, QC filtering, and imputation methods are available in Supplementary material online, Supplementary Methods; Table S2.

Association analysis

Detailed procedure is given in Supplementary material online, Methods. To summarize, association of imputed single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with DCM was investigated using a logistic regression model adjusted for sex and genome-wide genotype-derived principal components under the assumption of additive allele effects. A statistical threshold of 5 × 10−8 was used to declare genome-wide significance. To reveal potential multiple independent hits at the discovered loci, a conditional analysis was performed. When more than one significant SNP was found, subsequent haplotype analyses were conducted.

Replication of the findings was assessed with the same statistical methodologies in both replication cohorts, adopting one-tailed hypothesis and applying a Bonferroni correction procedure. After checking for the heterogeneity across studies, the replication cohorts’ results were meta-analysed, alone, and combined with the discovery results. Sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the robustness of the main findings according to several factors including sex and clinical characteristics of patients (Supplementary material online, Methods).

At each replicated associated locus, a regional association plot was performed using LocusZoom (http://locuszoom.sph.umich.edu/).

Genetic risk score analysis

The genetic risk score (GRS) was built upon SNPs associated with DCM and replicated in the current study. Association of the GRS with DCM risk was tested using logistic regression analysis (Supplementary material online, Methods).

Genetic heritability

The LD score regression approach10 was used to estimate the genome-wide genetic heritability underlying DCM and to calculate the genetic correlation between DCM and several cardiovascular and other traits capitalizing on the GWAS results available at the LD Hub (http://ldsc.broadinstitute.org/ldhub/).

Candidate culprit gene selection strategy

For each identified and replicated locus, a fine-mapping strategy (fully described in Supplementary material online, Methods) was deployed using in silico and experimental data to select the best candidates (Supplementary material online, Figure S1).

Cis-regulation features at associated single-nucleotide polymorphisms

DCM-associated SNPs [P-value ≤5 × 10−8 and/or in high LD (r 2 > 0.7) with the lead SNP] defined the associated ‘LD block’. Overlaps of LD blocks with DNA regulatory elements were checked by visualizing on the UCSC Genome Browser, human assembly hg19 (http://genome.ucsc.edu/; last accessed date: december 2020), the ENCODE3 DNase hypersensitivity sites (HS) and transcription factor (TF) chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) tracks produced on 125 and 130 cell lines, respectively. To detect left ventricle (LV)-specific putative regulatory regions, we enriched those tracks with H3K27ac, H3K4me1, and H3K4me3 histone marks of ENCODE LV samples (GSM908951, GSM910575, GSM910580), looked at ORegAnno predicted regulatory elements and checked sequence conservation in several vertebrates.

Topologically associating domains and intra-topologically associating domain chromatin interactions

Using LV topologically associating domains (TADs),11 and preferential chromatin interaction measured via promoter chromatin Hi-C (PCHi-C) on iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (iPSC-CM),12 we identified the candidate genes encompassed in TAD overlapping LD blocks. TAD boundaries were confirmed by in-house circular chromatin conformation capture (4C)-sequencing data (Supplementary material online, Figure S2, Table S17, Methods).

Biological insights into candidate genes

Cardiac expression level of each candidate was evaluated from RNA-seq data of the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project database22 (https://www.gtexportal.org/home; last accessed date: december 2020) and LV DCM explants produced by Heinig et al.13 The latter study also provided differential expression data between 97 DCM patients and 108 healthy donors. Genes displaying interesting expression features were scrutinized in publicly available resources for gene annotation and functions.

Annotation of associated single-nucleotide polymorphisms

LD block-associated SNPs were annotated using Annovar software and bioinformatics prediction of effects.14 , 15 Various in silico resources were interrogated to identify potential regulatory SNPs by checking their association with expression and splicing level [e and s quantitative trait loci (QTL)] in cardiac and skeletal muscle tissues (GTEx) and with blood DNA methylation levels (mQTL).16

GnomAD mutation tolerance score

The observed/expected (o/e) metric of GnomAD (https://GnomAD.broadinstitute.org/; last accessed date: december 2020) was used to evaluate the tolerance of candidate genes to loss of function and missense mutations. An o/e confidence interval score upper limit <0.35 for LoF and a Z-score of >3 for missense were indicative of a strong intolerance, as indicated at GnomAD.

Results

Main statistical findings

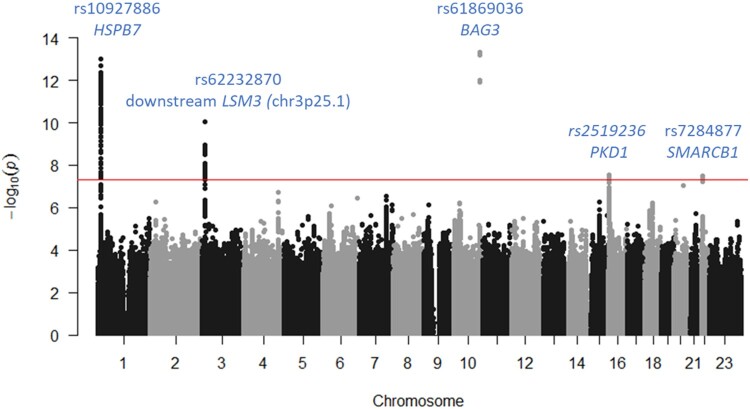

A total of 9 152 885 SNPs (8 945 131 autosomal and 207 754 on X chromosome) were tested for association with DCM in 2651 cases and 4329 controls. Results of the discovery GWAS are summarized in Figure 1, Supplementary material online, Figure S3, and Table 1. Five loci reached genome-wide significance. Two were already known, BAG3 (P = 4.7 × 10−14, rs61869036) and HSPB7 (P = 2.12 × 10−13, rs10927886). BAG3 rs61869036 was in complete LD with the nonsynonymous rs2234962 reported to associate with DCM7 and that was used thereafter as BAG3 lead SNP (P = 5.6 × 10−14). Three new loci were identified on chr3p25.1 (rs62232870, P = 8.7 × 10−11) downstream LSM3, chr16p13.3 (PKD1 rs2519236, P = 3.0 × 10−8) and chr22q11.23 (SMARCB1 rs7284877, P = 3.3 × 10−8). Regional association plots are shown in Supplementary material online, Figures S4–S8. Conditional GWAS adjusted for the five lead SNPs did not reveal any new genome-wide association signal (Supplementary material online, Figures S9 and S10).

Figure 1.

Manhattan plot summarizing the results of the discovery genome-wide association study.

Table 1.

Main association findings of the dilated cardiomyopathy genome-wide association study results

| rs62232870a | rs4684185b | rs148248535b,c | rs7284877b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosome | 3 | 3 | 16 | 22 |

| Position (GRCh37.p13) | 14257709 | 14272914 | 2183449 | 24155111 |

| Locus | LSM3 | LSM3 | PKD1 | SMARCB1 |

| Risk allele | A | C | T | C |

| Discovery | ||||

| RAFd | 0.23 | 0.70 | 0.82 | 0.81 |

| Imputation r 2 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.89 | 0.99 |

| Allelic OR [95% CI] | 1.36 [1.24–1.49] | 1.28 [1.17–1.40] | 1.35 [1.21–1.50] | 1.32 [1.20–1.46] |

| P | 8.7 × 10−11 | 8.4 × 10−9 | 3.0 × 10−8 | 3.3 × 10−8 |

| Replication | ||||

| Dutch study | ||||

| RAFd | 0.22 | 0.70 | 0.84 | 0.79 |

| Imputation r 2 | 0.95 | 0.99 | 0.92 | 0.99 |

| Allelic OR [95% CI] | 1.54 [1.00–2.35] | 1.45 [1.03–2.04] | 1.21 [0.77–1.90] | 1.75 [1.44–2.68] |

| P e | 0.024 | 0.017 | 0.199 | 4 × 10−3 |

| German study | ||||

| RAFd | 0.22 | 0.71 | 0.84 | 0.82 |

| Imputation r 2 | NAj | NAj | NAj | NAj |

| Allelic OR [95% CI] | 1.36 [1.08–1.71] | 1.19 [0.96–1.46] | 1.13 [0.88–1.46] | 1.26 [0.99–1.61] |

| P e | 5.6 × 10−3 | 0.046 | 0.172 | 0.031 |

| Sub meta-analysis | ||||

| Allelic OR [95% CI] | 1.38 [1.13–1.69] | 1.26 [1.05–1.51] | 1.16 [0.91–1.47] | 1.39 [1.12–1.72] |

| P f | 7.7 10−4 | 6 × 10−3 | 0.11 | 1.4 × 10−3 |

| Q g | 0.30 | 0.87 | 0.05 | 0.85 |

| I 2h | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| P het i | 0.58 | 0.35 | 0.81 | 0.36 |

| Combined discovery + replication | ||||

| Allelic OR [95% CI] | 1.36 [1.25–1.48] | 1.27 [1.18–1.37] | 1.31 [1.19–1.45] | 1.33 [1.22–1.46] |

| P f | 5.3 × 10−13 | 4.8 × 10−10 | 3.4 × 10−8 | 5.0 × 10−10 |

| Q g | 0.33 | 0.89 | 1.33 | 1.82 |

| I 2h | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| P het i | 0.85 | 0.64 | 0.51 | 0.40 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

The minor allele is the risk allele.

The major allele is the risk allele.

For German replication, association analysis was done with rs35786 serving as a proxy for rs148248535 (r 2 = 0.97).

Risk allele frequency.

One-sided P-value.

Two-sided combined P-value derived from a fixed effect meta-analysis of the discovery and replication results.

Cochrane’s Q estimates heterogeneity across studies.

I 2 index describes the magnitude of the heterogeneity.

P-value of the heterogeneity test across studies.

Not applicable.

At chr3p25.1, a second SNP, rs4684185, in negative LD with rs62232870 (r 2 = 0.12, D′ = −0.95), showed a high statistical association (P = 8.4 × 10−9). After adjustment on the lead SNP, a residual signal remained (P = 5 × 10−4) suggesting a more complex association pattern (Supplementary material online, Results; Supplementary material online, Table S3).

Replication analyses did not confirm PKD1 rs148248535 (P = 0.11) but confirmed the associations observed at chr3p25.1 (P = 7.70 × 10−4 and P = 6.0 × 10−3 for rs6223870 and rs4684185, respectively) and at chr22q11.23 (P = 1.40 × 10−3 for rs7284877) (Table 1).

In a combined meta-analysis of the discovery and replication findings, the resulting odds ratios for DCM were 1.36 [1.25–1.48] (P = 5.3 × 10−13) and 1.27 [1.18–1.37] (P = 4.8 × 10−10) for chr3p25.1 rs6223870 and rs4684185, respectively, and 1.33 [1.22–1.46] (P = 5.0 × 10−10) for chr22q11.23 SMARCB1 rs7284877, with no evidence for heterogeneity across studies (Table 1). The results were also robustly confirmed by stratified analyses on phenotypic and population subgroups (Supplementary material online, Tables S4–S6). GWASs stratified by sex did not reveal any new additional signal (Supplementary material online, Results; Supplementary material online, Figures S11 and S12).

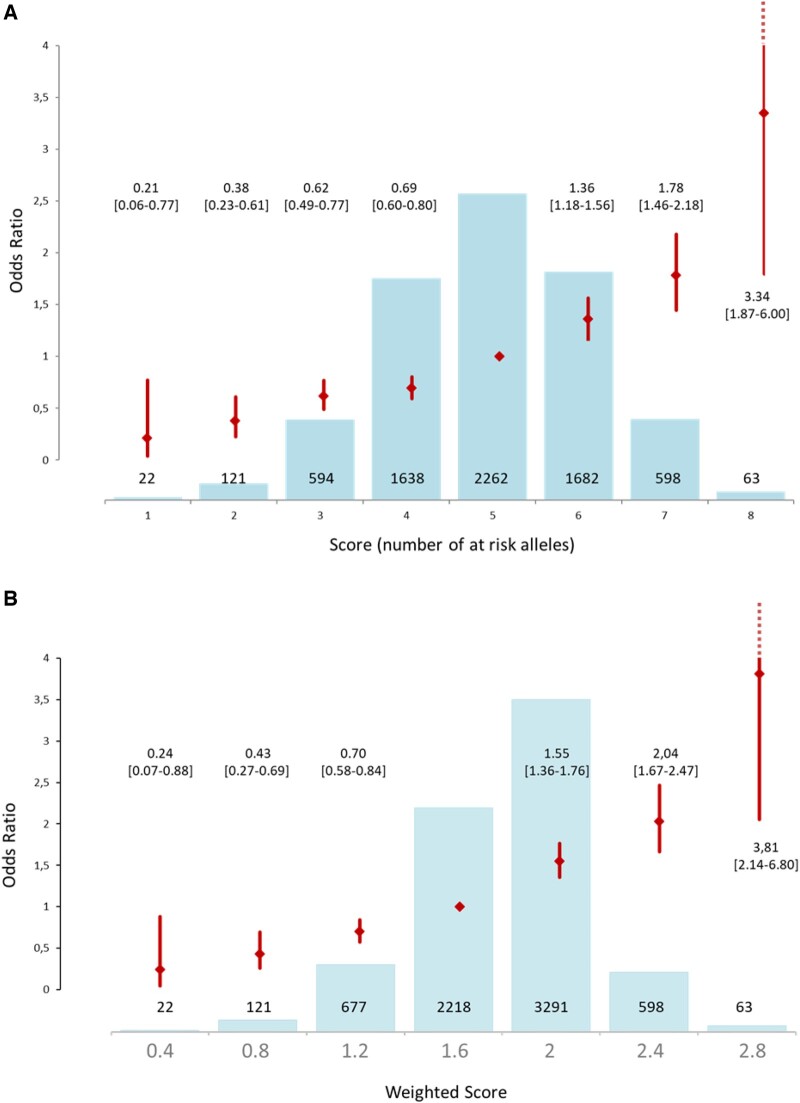

Genetic risk score analysis

Unweighted and weighted GRS, summarized in Figure 2 and Supplementary material online, Table S7, presented similar results. Briefly, the unweighted GRS showed a 3-fold increased risk of DCM for subjects with 8 risk alleles (3.34 [1.87–6.00]) and a 5-fold decreased for those having only one risk allele (0.21 [0.06–0.77]) as compared with individuals with 5 risk alleles (median of the referral population) (Figure 2A and Supplementary material online, Table S7A). Weighted GRS (continuous scale, Figure 2B and Supplementary material online, Table S7B; quintile distribution, Supplementary material online, Figure S13) presents similar results. A similar pattern was observed in the replication cohort (Supplementary material online, Results; Supplementary material online, Table S7). A significant association of the score was also detected in the subgroup of patients with left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (n = 2187; odds ratio 1.53 [1.05–2.23]) and a borderline one with prognosis (cardiac death/heart transplant) during follow-up (n = 503; odds ratio 1.23 [0.98–1.56]).

Figure 2.

(A) Unweighted Genetic Risk Score for the 6,980 individuals of the discovery cohort and associated OR taking score 5 (presence of 5 risk alleles) as reference. (B) Weighted* Genetic Risk Score for the 6,980 individuals of the discovery cohort and associated OR taking the score 1.6 as reference.

*Score of each SNP weighted by the beta value of this SNP in the sub meta-analysis of the two replication cohorts.

Heritability

The estimated genome-wide DCM heritability was 31 ± 8.4%. Genetic correlations between DCM and various cardiometabolic and lipid phenotypes were tested but did not reveal striking correlations (Supplementary material online, Table S8).

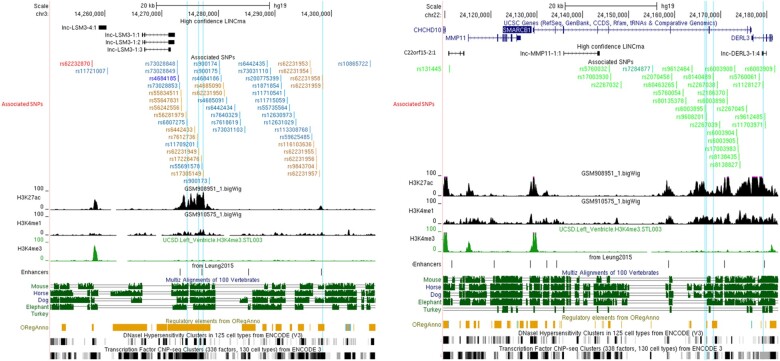

Candidate culprit gene selection strategy at chr3p25.1

As shown in Figure 3A, the top SNP, rs62232870, is located at the edge of an active enhancer region, distal to LSM3, as evidenced by H3K27ac and H3K4me3 LV histone marks. Those marks are absent in the seven ENCODE non-cardiomyocyte cell lines suggesting a cardiac tissue-specific expression. Vertebrates’ interspecies sequence conservation, predicted regulatory elements, DNAseI HS, and TF-binding sites support the regulatory activity of this region.

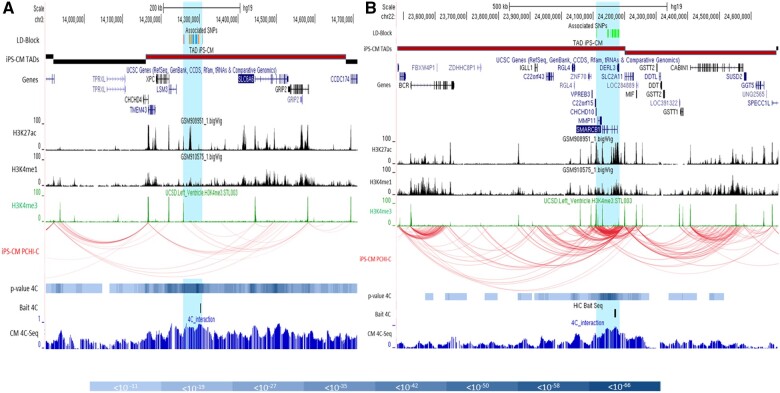

Figure 3.

Maps of regulatory DNA features for chromosome 3p25.1 (A) and 22q11.23 (B) linkage disequilibrium blocks. All single-nucleotide polymorphisms with an association P-value of <5 × 10−8 and/or in linkage disequilibrium (r 2 ≥ 0.7) with the lead single-nucleotide polymorphisms (rs62232870 in red; rs4684185 in dark blue; rs7284877 in dark green) are indicated. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in linkage disequilibrium with the lead single-nucleotide polymorphisms are coloured orange, light blue, and light green. Features associated with regulatory sequence elements are aligned under the associated single-nucleotide polymorphisms track: histone ChIP-seq signals in human left ventricle, OregAnno regulatory element score, vertebrates’ species conservation, DNaseI hypersensitivity, and ChiP-seq signal for chromatin-interacting proteins linked to transcription activity. Vertical blue lines highlight single-nucleotide polymorphisms with a Regulomedb prediction score below 4 (Supplementary material online,).

The rs62232870 associated LD block covers ∼50 kbp [chr3:14 257 356–14 307 016] overlapping with the partially independent rs4684185 associated LD block (Supplementary material online, Figure S5 and Supplementary material online, Table S9) where ENCODE H3K27ac and H3K4me1 marks and enhancers reported by Leung et al.11 are predicted (Figure 3). It is located in a predicted TAD spanning [chr3:14 160 000–14 680 000] (Figure 4A) that encompasses six genes (CHCHD4, TMEM43, XPC, LSM3, SLC6A6, and GRIP2) (Supplementary material online, Table S10). Using PCHi-C in iPSC-CM, H3K27ac/H3K4me1 enhancer marks inside the LD block specifically interact with the SLC6A6 and GRIP2 promoters (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Positional candidate genes located in topologically associating domains at chromosome 3p25.1 (left) and 22q11.23 (right) loci (Supplementary material online, Table S10). Delimitation of the topologically associating domains was based on publicly available iPSC-derived cardiomyocyte topologically associating domains that encompass the linkage disequilibrium block at both loci and confirmed by the results of in-house 4C-sequencing data produced on an iPSC-derived cardiomyocyte line from a donor (details in Supplementary material online); 4C baits are localized by a vertical black bar. Interaction P-values <10−8 are shown as a blue scale colour bar given below. Preferential chromatin interactions measured via promoter chromatin Hi-C on iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes revealed preferential contact inside topologically associating domains as shown by the red curves. Intra-topologically associating domain interactions allowed to establish candidate genes list prone to be regulated in cis by the linkage disequilibrium blocks (blue highlight). Specific DNA interactions are joining associated regions with histone enhancer marks (H3K27ac, H3K4me1, and H3K4me3).

The in-house 4C-seq results show significant interactions (P < 10−8) between the associated region bait and intra-TAD regional promoters/enhancers, confirming TAD boundaries. The highest interaction signals localized on the SLC6A6 promoter and intragenic enhancer and on the XPC/LSM3 promoter region (Figure 4A, P < 10−50; Supplementary material online, Table S11).

Each positional candidate gene (Supplementary material online, Table S10) is expressed in the LV and atrial appendage: TMEM43, CHCHD4, LSM3, SLC6A6, XPC, and GRIP2 (from the most to the least expressed). Moreover, XPC (P = 8.3 × 10−15) and SLC6A6 (P = 6.9 × 10−6) LV expressions were significantly increased in DCM patients compared to healthy donors (Supplementary material online, Table S12A), while LSM3 expression was significantly decreased (P = 7.6 × 10−8).

The rs62232870-associated LD block was screened for eQTL, sQTL, and mQTL. rs62232870 is not an eQTL for nearby genes but other SNPs in the LD block were significantly associated with SLC6A6 expression in atrial appendage (highest signal, rs62231957, P = 1.9 × 10−5) (Supplementary material online, Table S13 and Supplementary material online, Figure S14). No sQTL was present, but all the SNPs strongly associate with the methylation level of SLC6A6 CpGs (cg08926287, P < 10−28) and less significantly in three other genes (TMEM43, CHCHD4, XPC; 10−23 < P < 10−8). Interestingly, the partially independent rs4684185-associated LD block correlates even more strongly with the same mQTLs (cg08926287, P < 10−72 for SLC6A6) (Supplementary material online, Table S14).

In addition, gene tolerance to mutation based on GnomAD metrics only pinpoints SLC6A6 as a strongly evolutionarily constrained gene upon the candidates (Supplementary material online, Table S15).

Combining all the data available (Supplementary material online, Table S14 and Supplementary material online, Figure S16), SLC6A6 appeared as the strongest culprit gene at this locus.

Candidate culprit gene selection strategy at chr22q11.23 locus

The LD block extends over 70 kbp from the 5′ region of MMP11 and CHCHD10 to the 5′ region of DERL3 including SMARCB1 where the lead SNP maps to [chr22:24 110 180–24 182 174] (Supplementary material online, Figure S8 and Supplementary material online, Table S9). This region contained H3K27ac, H3K4me1, and H3K4me3 LV marks witnessing the presence of cardiac active promoters and enhancers and numerous other features (interspecies conservation, regulatory elements, DNAseI HS, and TF-binding sites) support its regulatory role (Figure 3B).

The LD block is located at the edge of two cardiomyocyte-predicted TADs covering 1.2 Mb [chr22:23 480 001–24 680 000] (Figure 4B) and the 21 genes covered by those TADs were considered as positional candidates (Supplementary material online, Table S10). Published PCHi-C showed a dense pattern of chromatin interaction linking the LD block with promoters inside the TAD: ZNF70, CHCHD10, MMP11, SMARCB1, DERL3, and SLC2A11 confirming the regulatory role of the region. In-house CM 4C-seq confirmed strong interactions with enhancer elements located close by (Figure 4B), especially with SMARCB1 and DERL3 (Supplementary material online, Table S16; P < 10−50).

The most highly expressed gene was CHCHD10, followed by GSTT1, DDT, SMARCB1, CABIN1, and SLC2A11, the other 15 genes being very weakly or not expressed. Differential expression was observed for CHCHD10 and, to a lesser extent, for DDT and SMARCB1 (Supplementary material online, Table S12B).

Supplementary material online, Table S13 presents the significant eSNPs in cardiac and skeletal muscle tissues. Among the six cardiac-expressed genes, only SMARCB1 expression was influenced by SNPs within the LD block (Supplementary material online, Figure S15). No sQTL was present, but all SNPs in the LD block associated with methylation level variation (mQTL) of nearby genes (Supplementary material online, Table S14) (strongest signals, SMARCB1-cg08219923 and DERL3-cg25907215, P < 10−200).

Finally, GnomAD mutation tolerance score only suggested SMARCB1 and BCR as genes under evolutionary constraints (Supplementary material online, Table S15).

Combining all the data available (Supplementary material online, Table S14 and Supplementary material online, Figure S17), SMARCB1 appears to be the strongest candidate at chr22q11.23 locus.

Discussion

By adopting a GWAS strategy performed in the largest DCM population assembled so far, we identified and replicated two new susceptibility loci while confirming two previously reported ones, HSPB7 and BAG3. Interestingly, some SNPs in the two new loci we identified as associated with DCM were recently associated with cardiac structure and function in the general population (with a normal average ejection fraction) (UK Biobank study).17 These authors also constructed polygenic risk scores and observed that some of these scores were associated with incident DCM cases (n = 388). The association with incident DCM was based on polygenic scores as a whole, therefore providing no association between single SNP/loci and DCM in this study.17

The first novel locus maps to chr3p25.1. The LD block extends over six genes two of which, TMEM43 and SLC6A6, are expressed in the heart and have been suspected to be involved in human cardiac disorders. Two SNPs at that locus, rs73028849 and rs11710541, were associated with left ventricular imaging in a general population (not in heart failure/DCM).17 Rare pathogenic variants in TMEM43 have been reported in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy18 and a homozygous missense mutation in SLC6A6 was described in a family with hypokinetic cardiomyopathy and retinal degeneration.19 Several evidences pinpointed SLC6A6 as the culprit gene (Supplementary material online, Figure S16). DCM-associated SNPs in this LD block were significantly associated with SLC6A6 expression in atrial appendage and methylation. They also specifically interact with SLC6A6 regulatory elements through chromatin interaction analysis. Remarkably, the GnomAD mutation tolerance score also suggests that SLC6A6 is the best candidate among the genes of the locus. SLC6A6 encodes a taurine transporter whose expression and activity regulates taurine, an amino acid with cyto-protective effects especially in the heart.20 Taurine deficiency was observed in several mammalian species with DCM and in a family with hypokinetic cardiomyopathy, while its supplementation in the same models and patients was associated with left ventricular function normalization.19 , 21 , 22 Accordingly, mice knockout for SLC6A6 exhibit taurine level depletion and present DCM.23 Interestingly, GTEx LV transcriptomic data show that the haplotype containing rs62232870-A risk allele is associated with the lowest SLC6A6 expression. A link between SLC6A6 depletion and impaired myocardial function is therefore emerging, and our finding of SLC6A6 association with DCM is remarkable in this context. Even though the underlying pathway leading to heart failure remains to be fully studied in humans, and efficacy of taurine supplementation remains to be fully demonstrated, our results may suggest the potential for a new therapeutic perspective through taurine administration or modulation.

The second novel DCM locus maps to chr22q11.23 where six positional candidates showed significant expression in the heart, of which three also presented differential left ventricular expression between DCM and healthy heart (CHCHD10, DDT, and SMARCB1). SMARCB1 (SWI/SNF-related matrix-associated actin-dependent regulator of chromatin subfamily b member 1) is the sole gene under the influence of the lead rs7284877 in the LV. Interestingly, rs7284877 is in complete LD with SMARCB1-rs5760054, SMARCB1-rs2070458, and DERL3-rs5760061, recently reported as associated in the general population with systolic left ventricular internal dimension and fractional shortening17 , 24 and in strong LD (r 2 = 0.8) with rs6003909, associated with left ventricular mass to end-diastolic volume ratio in a UK Biobank GWAS on heart disease.25 Although SMARCB1 function cannot be directly related to heart morphogenesis or function, its involvement in left ventricular dimension or function in a general population, in silico and data mining annotations, evolutionary constraints’ prediction, and, to a lesser extent, functional analysis, suggest this gene as the more convincing candidate gene at the locus (Supplementary material online, Figure S17).

This GWAS also provided an innovative estimate of the genome-wide heritability of the disease in Europeans (31 ± 8%), a value consistent with that (h 2 ∼ 30%) recently reported in a population of African origin.8 However, the four independent lead SNPs (BAG3, HSPB7, SLC6A6, and SMARCB1) only contribute to 2% of the heritability, suggesting the role of additional genetic factors and gene/gene and gene/environment interactions yet to be identified. Based upon those four SNPs, we developed the first GRS in DCM. This score may have practical implications by improving the management of subjects at risk for DCM or systolic dysfunction, such as patients taking drugs increasing the risk of myocardial dysfunction, or relatives in DCM families. However, further clinical studies are warranted to validate its clinical utility.

Since some genes, such as BAG3, can be both involved in monogenic and multifactorial DCM forms, we checked whether genes known to cause monogenic DCM forms could also present common SNPs associated with sporadic DCM (Supplementary material online, Table S18). Except for FLNC and FHOD3, none of the familial form genes presents statistically suggestive association signals. We also performed the exon sequencing of SLC6A6 and SMARCB1 genes in a cohort of 769 index DCM patients and detected three rare missense likely pathogenic variants in SLC6A6 (Supplementary material online, Table S19) that suggest a potential role of SLC6A6 in monogenic DCM, although this requires further functional studies to be able to conclude.

Despite its innovative findings, this study may have some limitations. First, we robustly identified two new DCM loci and convincing candidates but were not able to definitely demonstrate which culprit variants are responsible for the observed susceptibility to the disease. Further molecular and cellular investigations are needed to fill this gap. Second, despite being the largest GWAS ever performed on DCM, with both a discovery and a replication phase, our study may have been suboptimal in identifying common susceptibility alleles due to the absence of perfectly matched healthy controls for the British and US populations. Therefore, we performed our discovery GWAS on combined individual data while handling any potential hidden population stratification through adjustment on genetically-derived principal components. The robust replication of two out of three genome-wide significant associations in two European cohorts provides strong support for the validity of that strategy. Finally, our results do apply to sporadic DCM and cannot be extrapolated at that stage to familial DCM. The replication of the reported genetic associations in non-European ancestry populations as well as the analysis of familial forms of DCM, are now needed.

In conclusion, we identified two new genetic loci associated with DCM at chr3p25.1 and chr22q11.23, in which SLC6A6 and SMARCB1 stand out as the most likely culprit candidate genes. A GRS was built with a potential clinical perspective for the prediction of DCM or its prognosis but additional work is required to conclude about this potential application. These findings not only provide a better understanding of the genetic architecture of DCM but also identify new players in the pathophysiology of systolic heart failure, with the potential for new therapeutic developments, especially through taurine modulation.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal online.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding authors (S.G and P.C).

Translational perspective

We present the results of the largest genome-wide association study performed so far in dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), a leading cause of systolic heart failure. We identified two new DCM-associated loci and two strong culprit genes, SLC6A6 and SMARCB1, on chromosomes 3p25.1 and 22q11.23, respectively. A polygenic risk score was constructed to better predict the risk of DCM. Furthermore, SLC6A6 gene encodes a taurine transporter whose involvement in myocardial dysfunction is supported by numerous observations in humans and animals. This study sheds light on novel biological pathways underlying heart failure, and putative new therapeutic targets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Pablo Garcia-Pavia for the conduction of the Spanish iGeneTrain cohort; Christian Snijders Blok, Koen Braat, and Joost Sluijter for technical assistance in 4C-seq experiments; and Aarno Palotie, Susanna Lemmela, and Samuli Ripatti from FinnGen and PheWAS.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the GENMED Laboratory of Excellence on Medical Genomics [ANR-10-LABX-0013]; DETECTIN-HF project (ERA-CVD framework); Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris [PHRC programme hospitalier de recherche Clinique, AOM04141]; Délégation à la recherche clinique AP-HP [EMUL and PHRC n°AOM95082]; the ‘Fondation LEDUCQ’ [Eurogene Heart Failure network; 11CVD 01]; the PROMEX charitable foundation and the Société Française de Cardiologie/Fédération Française de Cardiologie. The SFB-TR19 registry was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG). The Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP) is part of the Comunity Medicine Research net of the University of Greifswald, Germany, funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research [Grants 01ZZ9603, 01ZZ0103, and 01ZZ0403]; the Ministry of Cultural Affairs and the Social Ministry of the Federal State of Mecklenburg-West Pomerania; and grants from the German Center for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK). The KORA study was initiated and financed by the Helmholtz Zentrum München – German Research Center for Environmental Health, funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and by the State of Bavaria. KORA research was supported at the Munich Center of Health Sciences (MC-Health), Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, as part of LMUinnovativ. Benjamin Meder is supported by grants from the Deutsches Zentrum für Herz-Kreislauf-Forschung (German Center for Cardiovascular Research, DZHK); the German Ministry of Education and Research [CaRNAtion, FKZ 031L0075B]; Informatics for Life (Klaus Tschira Foundation), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) and by an excellence fellowship of the Else Kröner Fresenius Foundation; Folkert Asselbergs by UCL Hospitals NIHR Biomedical Research Centre; and Magdalena Harakalova by the NWO VENI grant [no. 016.176.136]. David-Alexandre Trégouët is supported by the “EPIDEMIOM-VTE” Senior Chair from the Initiative of Excellence of the University of Bordeaux. Declan O’Reagan is supported by grants from the Medical Research Council, UK (MC-A651-53301); the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Imperial College Biomedical Research Centre; and the British Heart Foundation (RG/19/6/34387, RG/19/6/34387).

Conflict of interest: P.C. reports personal fees for consultancies, outside the present work, for Amicus, Pfizer, and Alnylam. L.T. is a member of the Trial committee and of the speakers’ bureau for SERVIER and of the Trial committee for CVIE Therapeutics (personal fees). M.K. reports personal fees from Novartis, Torrent, Bayer, Lilly, Astra Zeneca, Servier, and Sanofi. B.M. reports grants from Siemens AG, Else Kröner Fresenius Foundation, and DZHK during the conduct of the study; and personnal fees from Daiichi Sankyo, Pfizer, Bayer AG, Fleischhacker GmbH, Myokardia Inc/BMS, and AstraZeneca outside the submitted work. R.I. reports grants from Leducq Foundation, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Novartis, Servier, Vifor Pharma, AstraZeneca, and Bayer, outside the submitted work. T.C. reports grants from NHLBI, during the conduct of the study; grants from BMS outside the submitted work. S.B. reports grants and personal fees from Abbott Diagnostics, Bayer, SIEMENS, Singulex, Thermo Fisher, personal fees from Abott, Astra Zeneca, AMGEN, Medtronic, Pfizer, Roche, Novartis, and Siemens Diagnostics, outside the submitted work. Z.B. reports grants, personal fees and other from ERA-CVD programme, DETECTin-HF, outside the submitted work. D.O. reports grants and personal fees from Bayer, outside the submitted work. L.F. reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer, BMS Pfizer, Medtronic, and Novartis, outside the submitted work. P.d.G. reports personal fees and non-financial support from ASTRA-ZENECA, NOVARTIS, ACTELION, SERVIER, MSD-BAYER, personal fees from BOEHRINGER-INGELHEIM, VIFOR, ABBOTT, personal fees and non-financial support from MSD-BAYER, and non-financial support from AMGEN, outside the submitted work. L.T. reports personal fees from SERVIER, CVIE Therapeutics, outside the submitted work. The other authors declare no competing interest apart from the Funding section.

Contributor Information

Sophie Garnier, Sorbonne Université, INSERM, UMR-S1166, Research Unit on Cardiovascular Disorders, Metabolism and Nutrition, Team Genomics & Pathophysiology of Cardiovascular Diseases, Paris 75013, France; ICAN Institute for Cardiometabolism and Nutrition, Paris 75013, France.

Magdalena Harakalova, Department of Cardiology, Division Heart & Lungs, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands; Regenerative Medicine Center, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Stefan Weiss, Interfaculty Institute for Genetics and Functional Genomics, Department of Functional Genomics, University Medicine Greifswald, Greifswald, Germany; DZHK (German Centre for Cardiovascular Research), partner site Greifswald, Greifswald, Germany.

Michal Mokry, Department of Cardiology, Division Heart & Lungs, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands; Laboratory of Clinical Chemistry and Haematology, University Medical Center, Heidelberglaan 100, Utrecht, the Netherlands; Laboratory of Experimental Cardiology, University Medical Center Utrecht, Heidelberglaan 100, Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Vera Regitz-Zagrosek, Institute of Gender in Medicine and Center for Cardiovascular Research, Charite University Hospital, Berlin, Germany; DZHK (German Center for Cardiovascular Research), Berlin, Germany.

Christian Hengstenberg, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Cardiology, Medical University of Vienna, Austria; Department of Internal Medicine, Medical University of Regensburg, Germany.

Thomas P Cappola, Penn Cardiovascular Institute and Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Richard Isnard, Sorbonne Université, INSERM, UMR-S1166, Research Unit on Cardiovascular Disorders, Metabolism and Nutrition, Team Genomics & Pathophysiology of Cardiovascular Diseases, Paris 75013, France; ICAN Institute for Cardiometabolism and Nutrition, Paris 75013, France; Cardiology Department, APHP, Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, Paris, France.

Eloisa Arbustini, IRCCS Fondazione Policlinico San Matteo, Pavia, Italy.

Stuart A Cook, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, London, UK; National Heart Centre Singapore, Singapore; Duke-NUS, Singapore.

Jessica van Setten, Department of Cardiology, Division Heart & Lungs, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Jorg J A Calis, Department of Cardiology, Division Heart & Lungs, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands; Regenerative Medicine Center, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Hakon Hakonarson, Center for Applied Genomics, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Michael P Morley, Penn Cardiovascular Institute and Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Klaus Stark, Department of Genetic Epidemiology, University of Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany.

Sanjay K Prasad, National Heart Centre Singapore, Singapore; Royal Brompton Hospital, London, UK.

Jin Li, Center for Applied Genomics, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Declan P O'Regan, Medical Research Council Clinical Sciences Centre, Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London, South Kensington Campus, London SW7 2AZ, UK.

Maurizia Grasso, Centre for Inherited Cardiovascular Diseases—IRCCS Fondazione Policlinico San Matteo, Pavia, Italy.

Martina Müller-Nurasyid, Institute of Genetic Epidemiology, Helmholtz Zentrum München—German Research Center for Environmental Health, Neuherberg, Germany; IBE, Faculty of Medicine, LMU Munich, Germany; Department of Internal Medicine I (Cardiology), Hospital of the Ludwig-Maximilians-University (LMU) Munich, Munich, Germany.

Thomas Meitinger, Institute of Genetic Epidemiology, Helmholtz Zentrum München—German Research Center for Environmental Health, Neuherberg, Germany; IBE, Faculty of Medicine, LMU Munich, Germany; Institute of Human Genetics, Klinikum rechts der Isar, Technische Universität München, Munich, Germany.

Jean-Philippe Empana, Université de Paris, INSERM, UMR-S970, Integrative Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease, Paris, France.

Konstantin Strauch, Institute of Genetic Epidemiology, Helmholtz Zentrum München—German Research Center for Environmental Health, Neuherberg, Germany; IBE, Faculty of Medicine, LMU Munich, Germany; Institute of Medical Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Informatics (IMBEI), University Medical Center, Johannes Gutenberg University, Mainz 55101, Germany.

Melanie Waldenberger, Research unit of Molecular Epidemiology, Helmholtz Zentrum München—German Research Center for Environmental Health, Neuherberg, Germany; DZHK (German Centre for Cardiovascular Research), partner site Munich Heart Alliance, Munich, Germany.

Kenneth B Marguiles, Penn Cardiovascular Institute and Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Christine E Seidman, Department of Medicine and Genetics Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Brigham & Women's Cardiovascular Genetics Center, Boston, MA, USA.

Georgios Kararigas, Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Iceland, Vatnsmýrarvegur 16, 101 Reykjavík, Iceland.

Benjamin Meder, Institute for Cardiomyopathies Heidelberg, Heidelberg University, Germany; Stanford Genome Technology Center, Department of Genetics, Stanford Medical School, CA, USA.

Jan Haas, Institute for Cardiomyopathies Heidelberg, Heidelberg University, Germany.

Pierre Boutouyrie, Université de Paris, INSERM, UMR-S970, Integrative Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease, Paris, France; Cardiology Department, APHP, Georges Pompidou European Hospital, Paris, France.

Patrick Lacolley, INSERM U1116, Faculté de Médecine, Vandoeuvre-les-Nancy, France.

Xavier Jouven, Université de Paris, INSERM, UMR-S970, Integrative Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease, Paris, France; Cardiology Department, APHP, Georges Pompidou European Hospital, Paris, France.

Jeanette Erdmann, Medizinische Klinik und Poliklinik, Universitätsmedizin der Johannes-Gutenberg Universität Mainz, Mainz, Germany.

Stefan Blankenberg, Medizinische Klinik II, Universität Lübeck, Lübeck, Germany.

Thomas Wichter, Dept. of Cardiology and Angiology, Niels-Stensen-Kliniken Marienhospital Osnabrück, Heart Centre Osnabrück/Bad Rothenfelde, Osnabrück 49074, Germany.

Volker Ruppert, Klinik für Innere Medizin-Kardiologie UKGM GmbH Standort Marburg Baldingerstrasse, Marburg, Germany.

Luigi Tavazzi, Maria Cecilia Hospital, GVM Care and Research, Cotignola, Italy.

Olivier Dubourg, Université de Versailles-Saint Quentin, Hôpital Ambroise Paré, AP-HP, Boulogne, France.

Gérard Roizes, Institut de Génétique Humaine, UPR 1142, CNRS, Montpellier, France.

Richard Dorent, Service de Cardiologie, CHU Tenon, Paris, France.

Pascal de Groote, Service de Cardiologie, Hôpital Cardiologique, Lille, France.

Laurent Fauchier, Service de Cardiologie, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Trousseau, Tours, France.

Jean-Noël Trochu, Université de Nantes, CHU Nantes, CNRS, INSERM, l’institut du thorax, Nantes 44000, France.

Jean-François Aupetit, Département de pathologie cardiovasculaire, Hôpital Saint-Joseph-Saint-Luc, Lyon, France.

Zofia T Bilinska, Unit for Screening Studies in Inherited Cardiovascular Diseases, National Institute of Cardiology, Warsaw, Poland.

Marine Germain, Univ. Bordeaux, INSERM, BPH, U1219, Bordeaux 33000, France.

Uwe Völker, Interfaculty Institute for Genetics and Functional Genomics, Department of Functional Genomics, University Medicine Greifswald, Greifswald, Germany; DZHK (German Centre for Cardiovascular Research), partner site Greifswald, Greifswald, Germany.

Daiane Hemerich, Department of Cardiology, Division Heart & Lungs, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Ibticem Raji, AP-HP, Département de Génétique, Centre de Référence Maladies Cardiaques Héréditaires, Hôpital Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris, France.

Delphine Bacq-Daian, Centre National de Recherche en Génomique Humaine (CNRGH), Institut de Biologie François Jacob, CEA, Université Paris-Saclay, Evry 91057, France; Laboratory of Excellence GENMED (Medical Genomics).

Carole Proust, Univ. Bordeaux, INSERM, BPH, U1219, Bordeaux 33000, France.

Paloma Remior, Department of Cardiology, Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro, CIBERCV, Madrid, Spain.

Manuel Gomez-Bueno, Department of Cardiology, Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro, CIBERCV, Madrid, Spain.

Kristin Lehnert, DZHK (German Centre for Cardiovascular Research), partner site Greifswald, Greifswald, Germany; Department of Internal Medicine B, University Medicine Greifswald, Greifswald, Germany.

Renee Maas, Department of Cardiology, Division Heart & Lungs, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands; Regenerative Medicine Center, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Robert Olaso, Centre National de Recherche en Génomique Humaine (CNRGH), Institut de Biologie François Jacob, CEA, Université Paris-Saclay, Evry 91057, France; Laboratory of Excellence GENMED (Medical Genomics).

Ganapathi Varma Saripella, Sorbonne Université, INSERM, UMR-S1166, Research Unit on Cardiovascular Disorders, Metabolism and Nutrition, Team Genomics & Pathophysiology of Cardiovascular Diseases, Paris 75013, France; SLU Bioinformatics Infrastructure (SLUBI), PlantLink, Department of Plant Breeding, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Almas Allé 8, 750 07 Uppsala, Sweden.

Stephan B Felix, DZHK (German Centre for Cardiovascular Research), partner site Greifswald, Greifswald, Germany; Department of Internal Medicine B, University Medicine Greifswald, Greifswald, Germany.

Steven McGinn, Centre National de Recherche en Génomique Humaine (CNRGH), Institut de Biologie François Jacob, CEA, Université Paris-Saclay, Evry 91057, France; Laboratory of Excellence GENMED (Medical Genomics).

Laëtitia Duboscq-Bidot, Sorbonne Université, INSERM, UMR-S1166, Research Unit on Cardiovascular Disorders, Metabolism and Nutrition, Team Genomics & Pathophysiology of Cardiovascular Diseases, Paris 75013, France; ICAN Institute for Cardiometabolism and Nutrition, Paris 75013, France.

Alain van Mil, Department of Cardiology, Division Heart & Lungs, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands; Regenerative Medicine Center, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Céline Besse, Centre National de Recherche en Génomique Humaine (CNRGH), Institut de Biologie François Jacob, CEA, Université Paris-Saclay, Evry 91057, France; Laboratory of Excellence GENMED (Medical Genomics).

Vincent Fontaine, Sorbonne Université, INSERM, UMR-S1166, Research Unit on Cardiovascular Disorders, Metabolism and Nutrition, Team Genomics & Pathophysiology of Cardiovascular Diseases, Paris 75013, France; ICAN Institute for Cardiometabolism and Nutrition, Paris 75013, France.

Hélène Blanché, Laboratory of Excellence GENMED (Medical Genomics); Centre d'Etude du Polymorphisme Humain, Fondation Jean Dausset, Paris, France.

Flavie Ader, Sorbonne Université, INSERM, UMR-S1166, Research Unit on Cardiovascular Disorders, Metabolism and Nutrition, Team Genomics & Pathophysiology of Cardiovascular Diseases, Paris 75013, France; APHP, UF Cardiogénétique et Myogénétique, service de Biochimie métabolique, Hôpital universitaire Pitié-Salpêtrière Paris, France; Faculté de Pharmacie Paris Descartes, Département 3, Paris 75006, France.

Brendan Keating, Division of Transplantation, Department of Surgery, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Angélique Curjol, AP-HP, Département de Génétique, Centre de Référence Maladies Cardiaques Héréditaires, Hôpital Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris, France.

Anne Boland, Centre National de Recherche en Génomique Humaine (CNRGH), Institut de Biologie François Jacob, CEA, Université Paris-Saclay, Evry 91057, France; Laboratory of Excellence GENMED (Medical Genomics).

Michel Komajda, Sorbonne Université, INSERM, UMR-S1166, Research Unit on Cardiovascular Disorders, Metabolism and Nutrition, Team Genomics & Pathophysiology of Cardiovascular Diseases, Paris 75013, France; ICAN Institute for Cardiometabolism and Nutrition, Paris 75013, France; Cardiology Department, Groupe Hospitalier Paris Saint Joseph, Paris, France.

François Cambien, Univ. Bordeaux, INSERM, BPH, U1219, Bordeaux 33000, France.

Jean-François Deleuze, Centre National de Recherche en Génomique Humaine (CNRGH), Institut de Biologie François Jacob, CEA, Université Paris-Saclay, Evry 91057, France; Laboratory of Excellence GENMED (Medical Genomics); Centre d'Etude du Polymorphisme Humain, Fondation Jean Dausset, Paris, France.

Marcus Dörr, DZHK (German Centre for Cardiovascular Research), partner site Greifswald, Greifswald, Germany; Department of Internal Medicine B, University Medicine Greifswald, Greifswald, Germany.

Folkert W Asselbergs, Department of Cardiology, Division Heart & Lungs, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands; Institute of Cardiovascular Science, Faculty of Population Health Sciences, University College London, London, UK; Health Data Research UK and Institute of Health Informatics, University College London, London, UK.

Eric Villard, Sorbonne Université, INSERM, UMR-S1166, Research Unit on Cardiovascular Disorders, Metabolism and Nutrition, Team Genomics & Pathophysiology of Cardiovascular Diseases, Paris 75013, France; ICAN Institute for Cardiometabolism and Nutrition, Paris 75013, France.

David-Alexandre Trégouët, Univ. Bordeaux, INSERM, BPH, U1219, Bordeaux 33000, France; Laboratory of Excellence GENMED (Medical Genomics).

Philippe Charron, Sorbonne Université, INSERM, UMR-S1166, Research Unit on Cardiovascular Disorders, Metabolism and Nutrition, Team Genomics & Pathophysiology of Cardiovascular Diseases, Paris 75013, France; ICAN Institute for Cardiometabolism and Nutrition, Paris 75013, France; Cardiology Department, APHP, Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, Paris, France; AP-HP, Département de Génétique, Centre de Référence Maladies Cardiaques Héréditaires, Hôpital Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris, France.

References

- 1. Elliott P, Andersson B, Arbustini E, Bilinska Z, Cecchi F, Charron P, Dubourg O, Kühl U, Maisch B, McKenna WJ, Monserrat L, Pankuweit S, Rapezzi C, Seferovic P, Tavazzi L, Keren A. Classification of the cardiomyopathies: a position statement from the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur Heart J 2007;29:270–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jefferies JL, Towbin JA. Dilated cardiomyopathy. Lancet 2010;375:752–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tayal U, Prasad S, Cook SA. Genetics and genomics of dilated cardiomyopathy and systolic heart failure. Genome Med 2017;9:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pinto YM, Elliott PM, Arbustini E, Adler Y, Anastasakis A, Böhm M, Duboc D, Gimeno J, de Groote P, Imazio M, Heymans S, Klingel K, Komajda M, Limongelli G, Linhart A, Mogensen J, Moon J, Pieper PG, Seferovic PM, Schueler S, Zamorano JL, Caforio ALP, Charron P. Proposal for a revised definition of dilated cardiomyopathy, hypokinetic non-dilated cardiomyopathy, and its implications for clinical practice: a position statement of the ESC working group on myocardial and pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J 2016;37:1850–1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Harakalova M, Kummeling G, Sammani A, Linschoten M, Baas AF, van der Smagt J, Doevendans PA, van Tintelen JP, Dooijes D, Mokry M, Asselbergs FW. A systematic analysis of genetic dilated cardiomyopathy reveals numerous ubiquitously expressed and muscle-specific genes. Eur J Heart Fail 2015;17:484–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aragam KG, Chaffin M, Levinson RT, McDermott G, Choi SH, Shoemaker MB, Haas ME, Weng L-C, Lindsay ME, Smith JG, Newton-Cheh C, Roden DM, London B, Wells QS, Ellinor PT, Kathiresan S, Lubitz SA, Bloom HL, Dudley SC, Shalaby AA, Weiss R, Gutmann R, Saba S, GRADE Investigators. Phenotypic refinement of heart failure in a national biobank facilitates genetic discovery. Circulation 2019;139:489–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Esslinger U, Garnier S, Korniat A, Proust C, Kararigas G, Müller-Nurasyid M, Empana J-P, Morley MP, Perret C, Stark K, Bick AG, Prasad SK, Kriebel J, Li J, Tiret L, Strauch K, O'Regan DP, Marguiles KB, Seidman JG, Boutouyrie P, Lacolley P, Jouven X, Hengstenberg C, Komajda M, Hakonarson H, Isnard R, Arbustini E, Grallert H, Cook SA, Seidman CE, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Cappola TP, Charron P, Cambien F, Villard E. Exome-wide association study reveals novel susceptibility genes to sporadic dilated cardiomyopathy. PLoS One 2017;12:e0172995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xu H, Dorn GW, Shetty A, Parihar A, Dave T, Robinson SW, Gottlieb SS, Donahue MP, Tomaselli GF, Kraus WE, Mitchell BD, Liggett SB. A genome-wide association study of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy in African Americans. J Pers Med 2018;8:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Norton N, Li D, Rieder MJ, Siegfried JD, Rampersaud E, Züchner S, Mangos S, Gonzalez-Quintana J, Wang L, McGee S, Reiser J, Martin E, Nickerson DA, Hershberger RE. Genome-wide studies of copy number variation and exome sequencing identify rare variants in BAG3 as a cause of dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet 2011;88:273–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zheng J, Erzurumluoglu AM, Elsworth BL, Kemp JP, Howe L, Haycock PC, Hemani G, Tansey K, Laurin C, Pourcain BS, Warrington NM, Finucane HK, Price AL, Bulik-Sullivan BK, Anttila V, Paternoster L, Gaunt TR, Evans DM, Neale BM ; Early Genetics and Lifecourse Epidemiology (EAGLE) Eczema Consortium. LD Hub: a centralized database and web interface to perform LD score regression that maximizes the potential of summary level GWAS data for SNP heritability and genetic correlation analysis. Bioinformatics 2017;33:272–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Leung D, Jung I, Rajagopal N, Schmitt A, Selvaraj S, Lee AY, Yen C-A, Lin S, Lin Y, Qiu Y, Xie W, Yue F, Hariharan M, Ray P, Kuan S, Edsall L, Yang H, Chi NC, Zhang MQ, Ecker JR, Ren B. Integrative analysis of haplotype-resolved epigenomes across human tissues. Nature 2015;518:350–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Montefiori LE, Sobreira DR, Sakabe NJ, Aneas I, Joslin AC, Hansen GT, Bozek G, Moskowitz IP, McNally EM, Nóbrega MA. A promoter interaction map for cardiovascular disease genetics. eLife 2018;7:e35788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Heinig M, Adriaens ME, Schafer S, van Deutekom HWM, Lodder EM, Ware JS, Schneider V, Felkin LE, Creemers EE, Meder B, Katus HA, Rühle F, Stoll M, Cambien F, Villard E, Charron P, Varro A, Bishopric NH, George AL, Dos Remedios C, Moreno-Moral A, Pesce F, Bauerfeind A, Rüschendorf F, Rintisch C, Petretto E, Barton PJ, Cook SA, Pinto YM, Bezzina CR, Hubner N. Natural genetic variation of the cardiac transcriptome in non-diseased donors and patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Genome Biol 2017;18:170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Boyle AP, Hong EL, Hariharan M, Cheng Y, Schaub MA, Kasowski M, Karczewski KJ, Park J, Hitz BC, Weng S, Cherry JM, Snyder M. Annotation of functional variation in personal genomes using RegulomeDB. Genome Res 2012;22:1790–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Smedley D, Schubach M, Jacobsen JOB, Köhler S, Zemojtel T, Spielmann M, Jäger M, Hochheiser H, Washington NL, McMurry JA, Haendel MA, Mungall CJ, Lewis SE, Groza T, Valentini G, Robinson PN. A Whole-genome analysis framework for effective identification of pathogenic regulatory variants in Mendelian disease. Am J Hum Genet 2016;99:595–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lemire M, Zaidi SHE, Ban M, Ge B, Aïssi D, Germain M, Kassam I, Wang M, Zanke BW, Gagnon F, Morange P-E, Trégouët D-A, Wells PS, Sawcer S, Gallinger S, Pastinen T, Hudson TJ. Long-range epigenetic regulation is conferred by genetic variation located at thousands of independent loci. Nat Commun 2015;6:6326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pirruccello JP, Bick A, Wang M, Chaffin M, Friedman S, Yao J, Guo X, Venkatesh BA, Taylor KD, Post WS, Rich S, Lima JAC, Rotter JI, Philippakis A, Lubitz SA, Ellinor PT, Khera AV, Kathiresan S, Aragam KG. Analysis of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in 36,000 individuals yields genetic insights into dilated cardiomyopathy. Nat Commun 2020;11:2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dominguez F, Zorio E, Jimenez-Jaimez J, Salguero-Bodes R, Zwart R, Gonzalez-Lopez E, Molina P, Bermúdez-Jiménez F, Delgado JF, Braza-Boïls A, Bornstein B, Toquero J, Segovia J, Van Tintelen JP, Lara-Pezzi E, Garcia-Pavia P. Clinical characteristics and determinants of the phenotype in TMEM43 arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy type 5. Heart Rhythm 2020;17:945–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ansar M, Ranza E, Shetty M, Paracha SA, Azam M, Kern I, Iwaszkiewicz J, Farooq O, Pournaras CJ, Malcles A, Kecik M, Rivolta C, Muzaffar W, Qurban A, Ali L, Aggoun Y, Santoni FA, Makrythanasis P, Ahmed J, Qamar R, Sarwar MT, Henry LK, Antonarakis SE. Taurine treatment of retinal degeneration and cardiomyopathy in a consanguineous family with SLC6A6 taurine transporter deficiency. Hum Mol Genet 2020;29:618–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xu YJ, Arneja AS, Tappia PS, Dhalla NS. The potential health benefits of taurine in cardiovascular disease. Exp Clin Cardiol 2008;13:57–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pion PD, Kittleson MD, Rogers QR, Morris JG. Myocardial failure in cats associated with low plasma taurine: a reversible cardiomyopathy. Science 1987;237:764–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kaplan JL, Stern JA, Fascetti AJ, Larsen JA, Skolnik H, Peddle GD, Kienle RD, Waxman A, Cocchiaro M, Gunther-Harrington CT, Klose T, LaFauci K, Lefbom B, Machen Lamy M, Malakoff R, Nishimura S, Oldach M, Rosenthal S, Stauthammer C, O’Sullivan L, Visser LC, William R, Ontiveros E. Taurine deficiency and dilated cardiomyopathy in golden retrievers fed commercial diets. PLoS One 2018;13:e0209112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ito T, Oishi S, Takai M, Kimura Y, Uozumi Y, Fujio Y, Schaffer SW, Azuma J. Cardiac and skeletal muscle abnormality in taurine transporter-knockout mice. J Biomed Sci 2010;17: S20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kanai M, Akiyama M, Takahashi A, Matoba N, Momozawa Y, Ikeda M, Iwata N, Ikegawa S, Hirata M, Matsuda K, Kubo M, Okada Y, Kamatani Y. Genetic analysis of quantitative traits in the Japanese population links cell types to complex human diseases. Nat Genet 2018;50:390–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aung N, Vargas JD, Yang C, Cabrera CP, Warren HR, Fung K, Tzanis E, Barnes MR, Rotter JI, Taylor KD, Manichaikul AW, Lima JAC, Bluemke DA, Piechnik SK, Neubauer S, Munroe PB, Petersen SE. Genome-wide analysis of left ventricular image-derived phenotypes identifies fourteen loci associated with cardiac morphogenesis and heart failure development. Circulation 2019;140:1318–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding authors (S.G and P.C).

Translational perspective

We present the results of the largest genome-wide association study performed so far in dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), a leading cause of systolic heart failure. We identified two new DCM-associated loci and two strong culprit genes, SLC6A6 and SMARCB1, on chromosomes 3p25.1 and 22q11.23, respectively. A polygenic risk score was constructed to better predict the risk of DCM. Furthermore, SLC6A6 gene encodes a taurine transporter whose involvement in myocardial dysfunction is supported by numerous observations in humans and animals. This study sheds light on novel biological pathways underlying heart failure, and putative new therapeutic targets.