Abstract

Introduction

Ubrogepant is an oral, small-molecule calcitonin gene–related peptide receptor antagonist approved for the acute treatment of migraine. The efficacy and safety of ubrogepant were demonstrated in two pivotal phase 3, single-attack, randomized, placebo-controlled trials (ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II).

Methods

We conducted a post hoc analysis of pooled data from the ACHIEVE trials to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of ubrogepant 50 mg (the only dose evaluated in both trials) versus placebo across a large population of participants with migraine. The coprimary efficacy outcomes were pain freedom and absence of the most bothersome migraine-associated symptom (including photophobia, phonophobia, and nausea) at 2 h post dose. Secondary outcomes included pain relief at 2 h post dose, sustained pain relief and pain freedom from 2 to 24 h, and absence of specific migraine-associated symptoms at 2 h post dose.

Results

A total of 2240 eligible participants were randomized to placebo (n = 1122) or ubrogepant 50 mg (n = 1118) in the ACHIEVE trials. Pain freedom at 2 h was reported in 13.0% of participants in the pooled placebo group and 20.5% in the pooled ubrogepant 50 mg group (odds ratio [OR] 1.72; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.34, 2.22; P < 0.001). Absence of the most bothersome migraine-associated symptom at 2 h was reported by 27.6% in the pooled placebo group and by 38.7% in the pooled ubrogepant 50 mg group (OR 1.68; 95% CI 1.37, 2.05; P < 0.001). Adverse events (AEs) within 48 h after the initial or optional second dose were reported by 11.5 and 11.2% of participants in the pooled placebo and pooled ubrogepant 50 mg groups, respectively. The most common AE was nausea (1.8 and 1.9%, respectively). No serious AEs related to treatment or discontinuations due to AEs were reported.

Conclusion

These results further support the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifiers: ACHIEVE I: NCT02828020; ACHIEVE II: NCT02867709

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40120-021-00234-7.

Keywords: Calcitonin gene–related peptide, Gepant, Headache, Migraine, Ubrogepant

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Migraine is a highly prevalent and burdensome chronic disease with episodic attacks that are often incapacitating and characterized by headache pain as well as neurologic and autonomic symptoms. |

| Ubrogepant is an oral, small-molecule calcitonin gene–related peptide receptor antagonist approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the acute treatment of migraine with or without aura in adults. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Pooled analysis of the ubrogepant 50 mg and placebo groups from the pivotal ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II trials demonstrated significant improvements in pain relief, pain freedom, photophobia, and phonophobia with ubrogepant compared with placebo. |

| These results further support the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.13664162.

Introduction

Acute treatments for migraine aim to reverse or stop the progression of an individual attack, while preventive treatments are designed to reduce the frequency, severity, and duration of attacks [1–3]. Historically, medications used for the acute treatment of migraine have included analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), opioids, barbiturates, ergot derivatives, and triptans [4, 5]. In this acute treatment landscape, approximately 30–50% of those with migraine reported dissatisfaction with available acute medications [6, 7]. Poor efficacy and adverse events (AEs) are key drivers of low satisfaction with available treatments, including triptans [8, 9]. A US claims-based study found approximately half of new triptan users did not refill their initial triptan prescription within 1 year, and half of these users filled an opioid prescription [10]. Additionally, a substantial proportion of people with migraine have a history of cardiovascular events that contraindicate or cardiovascular risk factors that may limit the use of triptans, ergot derivatives, and NSAIDs [11–13]. Inadequate treatment of migraine attacks and the overuse of currently available acute medications may lead to uncontrolled migraine and medication overuse, potentially resulting in medication overuse headache, disease progression, and the development of chronic migraine, further compounding the burden and disability of the disease [14–16]. New acute treatment options for migraine that do not increase the risk of medication overuse headache and improve tolerability and efficacy profiles are needed to provide improved management of migraine.

Ubrogepant is an oral, small-molecule calcitonin gene–related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonist approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the acute treatment of migraine with or without aura in adults [17]. The efficacy and safety of ubrogepant were demonstrated in two phase 3, single-attack, placebo-controlled trials (ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II) [18, 19]. Both approved doses of ubrogepant (50 and 100 mg) met the co-primary efficacy endpoints of achieving pain freedom and absence of the most bothersome migraine-associated symptoms (including photophobia, phonophobia, or nausea) at 2 h post dose at significantly greater rates than placebo (P ≤ 0.01) [18, 19]. Ubrogepant 50 mg and ubrogepant 100 mg also significantly improved the rates of participant-reported pain relief, satisfaction with medication, and return to normal function compared with placebo [18–20].

Safety and tolerability are important factors when considering potential acute treatments for migraine. Pooled analyses of data from multiple clinical trials are important in order to assess potential safety signals that may not have been observed in smaller, single-trial samples. Both of the pivotal trials (ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II) included ubrogepant 50 mg and placebo treatment groups, allowing for the post hoc analysis of pooled data from the individual trials reported here to evaluate the efficacy and safety across a large population of participants with migraine. Furthermore, given the identical trial design, we conducted an analysis of pooled efficacy measures across shared dose groups to help provide a more robust estimate of the treatment effect of ubrogepant.

Methods

Detailed descriptions of the methods for each ACHIEVE trial have been reported previously [18, 19]. ACHIEVE I (NCT02828020) and ACHIEVE II (NCT02867709) were both multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, single-attack phase 3 trials conducted in the USA (ACHIEVE I: 89 sites; ACHIEVE II: 99 sites). The ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II trials were conducted in conformance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments, or the laws and regulations of the country in which the research was conducted, whichever afforded the greater protection to the individual. Trial protocols were approved by each individual research center’s institutional review board. All participants provided written informed consent before initiation of trial procedures. All authors had full access to all data from both studies.

Participants and Trial Design

Complete inclusion and exclusion criteria are published elsewhere [18, 19]. Briefly, eligible participants were 18–75 years of age, had a history of migraine with or without aura for at least 1 year consistent with a diagnosis according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version) criteria [21], and must have experienced 2–8 migraine attacks with moderate to severe headache pain in each of the 3 months before screening.

In ACHIEVE I, participants were randomized 1:1:1 to placebo, ubrogepant 50 mg, or ubrogepant 100 mg; in ACHIEVE II, participants were randomized 1:1:1 to placebo, ubrogepant 25 mg, or ubrogepant 50 mg. In each trial, randomization was stratified by previous response to triptans and current use of concomitant preventive medication for migraine. Participants took the assigned study medication as soon as possible and at ≤ 4 h after headache onset to treat a migraine attack with moderate or severe migraine headache pain accompanied by at least one migraine-associated symptom (photophobia, phonophobia, or nausea). Participants could take an optional second dose (randomized allocation) or rescue medication for the treatment of migraine with moderate or severe headache pain starting from 2 to 48 h after the initial dose of study medication.

Efficacy Assessments

In both ACHIEVE I and II, participants rated headache pain severity as none, mild, moderate, or severe and recorded the presence or absence of migraine-associated symptoms (photophobia, phonophobia, and nausea) before dosing and at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 24, and 48 h after the initial dose; at the time of the optional second dose (if taken); and 2 h after the second dose. Participants identified the most bothersome migraine-associated symptom (photophobia, phonophobia, or nausea) before taking study medication.

In both trials, the co-primary efficacy outcomes were participant-assessed pain freedom (i.e., reduction from moderate or severe headache pain at baseline to no pain) and absence of the most bothersome migraine-associated symptom at 2 h after the initial dose. The secondary efficacy outcomes were pain relief (defined as reduction of headache pain severity from moderate or severe to mild or none) at 2 h, sustained pain relief from 2 to 24 h and from 2 to 48 h, sustained pain freedom from 2 to 24 h and from 2 to 48 h, and absence of each migraine-associated symptom (photophobia, phonophobia, and nausea) at 2 h. Sustained pain relief (and pain freedom) from 2 to 24 h was defined as pain relief (or pain freedom) without taking a second dose of study medication or rescue medication and with no occurrence thereafter of a moderate or severe (mild, moderate, or severe) headache during the period 2–24 h post dose.

Safety Assessments

Adverse events that occurred within 48 h after taking the initial or optional second dose and within 30 days after taking any dose of the study medication were monitored and recorded. Additional safety assessments included clinical laboratory test results, vital signs, electrocardiograms (ECGs), and the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS). Independent data safety monitoring boards reviewed unblinded safety data and summary reports from each trial to identify any safety issues and trends, and to make recommendations to the sponsor, including modification or early termination of a trial, if emerging data showed unexpected and clinically significant AEs. Both trials evaluated hepatic safety laboratory values as prespecified AEs of special interest. An independent Hepatic Events Adjudication Committee reviewed all posttreatment elevations of alanine aminotransferase and/or aspartate aminotransferase values that were at least threefold the value of the upper limit of the normal range.

Statistical Analysis

To improve precision and the likelihood of detecting lower frequency events, efficacy and safety data from the placebo and ubrogepant 50 mg arms (the only dose evaluated in both trials) were pooled in this post hoc analysis. The 25 mg (ACHIEVE II) and 100 mg (ACHIEVE I) treatment groups were single-trial dose groups and could not be included in the pooled efficacy analysis. However, safety data for the 25 mg and 100 mg dose groups are given in Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM) Table S1 for comparison to inform any dose effects.

The pooled primary efficacy analysis was conducted using the pooled modified intent-to-treat (mITT) population, which included randomized participants who received at least one dose of study medication, recorded baseline migraine headache severity, and reported at least one post-dose migraine headache severity rating or migraine-associated symptom outcome at or before 2 h after the initial dose. The pooled safety population included all randomized participants who received at least one dose of study medication (n = 954) and provided at least a 95% probability of observing an adverse event with an incidence rate of 0.31% or higher. The co-primary efficacy variables of pain freedom and absence of the most bothersome migraine-associated symptom at 2 h post dose were analyzed using logistic regression with categorical terms for treatment group, historical triptan response, use of medication for prevention of migraine, baseline headache severity, and baseline most bothersome migraine-associated symptom (only for most bothersome symptom variables). Secondary outcome measures of pain relief and absence of photophobia, phonophobia, and nausea were analyzed using similar logistic regression models. All efficacy outcomes were analyzed in the subpopulation of participants with available data. Comparisons between the pooled ubrogepant 50 mg group and the pooled placebo group were based on model-derived odds ratios (ORs) and their associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All statistical tests were two-sided hypothesis tests performed at the 5% significance level. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

A total of 2240 eligible participants were randomly assigned to placebo (n = 1122) or ubrogepant 50 mg (n = 1118) in ACHIEVE I or ACHIEVE II (Fig. 1). Of these, 1938 (placebo, n = 984; ubrogepant 50 mg, n = 954) were included in the pooled safety population and 1799 (placebo, n = 912; ubrogepant 50 mg, n = 887) constituted the pooled mITT population. Demographic characteristics were similar across treatment groups in the pooled mITT population (Table 1). Overall, the mean age was 41 years and most participants were female (90%) and white (82%). Approximately 24% of participants reported current use of a preventive migraine medication. The most bothersome migraine-associated symptom for the treated migraine attack was photophobia in 56% of participants, phonophobia in 24%, and nausea in 19%.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT flow diagram of the pooled analysis of ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II. a The mITT population included all randomized participants who received at least one dose of the study medication, recorded baseline migraine headache severity, and reported at least one post-dose migraine headache severity rating or migraine-associated symptom outcome at or before 2 h after the initial dose. mITT Modified intent-to-treat

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics

| Pooled mITT population | Pooled placebo (n = 912) | Pooled ubrogepant 50 mg (n = 887) | Total (n = 1799) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 41.1 (11.9) | 40.4 (12.1) | 40.8 (12.0) |

| Median (min, max) | 40.0 (18, 74) | 40.0 (18, 75) | 40.0 (18, 75) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 809 (88.7) | 803 (90.5) | 1612 (89.6) |

| Male | 103 (11.3) | 84 (9.5) | 187 (10.4) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 754 (82.7) | 728 (82.1) | 1482 (82.4) |

| Black or African American | 126 (13.8) | 135 (15.2) | 261 (14.5) |

| Asian | 13 (1.4) | 9 (1.0) | 22 (1.2) |

| American Indian or Alaska native | 6 (0.7) | 5 (0.6) | 11 (0.6) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 3 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) | 5 (0.3) |

| Multiplea | 10 (1.1) | 8 (0.9) | 198 (1.) |

| Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, n (%) | 132 (14.5) | 146 (6.5) | 278 (15.5) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 29.9 (7.6) | 30.3 (7.8) | 30.1 (7.7) |

| Historical triptan response, n (%) | |||

| Triptan responderb | 350 (38.4) | 332 (37.4) | 682 (37.9) |

| Triptan insufficient responderc | 223 (24.5) | 228 (25.7) | 451 (25.1) |

| Triptan naive | 339 (37.2) | 327 (36.9) | 666 (37.0) |

| Concomitant preventive medication for migraine,d n (%) | 217 (23.8) | 212 (23.9) | 429 (23.8) |

| Baseline headache severity of treated migraine attack, n (%) | |||

| Moderate pain | 545 (59.8) | 549 (61.9) | 1094 (60.8) |

| Severe pain | 367 (40.2) | 338 (38.1) | 705 (39.2) |

| Migraine-associated symptoms of treated attack, n (%) | |||

| Photophobia | 820 (89.9) | 810 (91.3) | 1630 (90.6) |

| Phonophobia | 732 (80.3) | 689 (77.7) | 1421 (79.0) |

| Nausea | 571 (62.6) | 534 (60.2) | 1105 (61.4) |

| Vomiting | 48 (5.3) | 48 (5.4) | 96 (5.3) |

| Most bothersome migraine-associated symptom of treated attack, n (%) | |||

| Photophobia | 499 (54.7) | 513 (57.8) | 1012 (56.3) |

| Phonophobia | 234 (25.7) | 197 (22.2) | 431 (24.0) |

| Nausea | 177 (19.4) | 173 (19.5) | 350 (19.5) |

| Missing | 2 (0.2) | 4 (0.5) | 6 (0.3) |

BMI Body mass index, mITT modified intent-to-treat, SD standard deviation

aParticipants who report ≥ 2 races, including participants who report white and ≥ 1 other race

bA triptan responder was defined as a participant who met any of the following criteria: (1) current use of a triptan or had used a triptan in the past 6 months, and on the occasions that a triptan dose was taken, achieved pain freedom (no headache pain) at 2 h post dose on more than half of those occasions; (2) in the past had a response to a triptan as described above, but no longer used a triptan for some other reason

cA triptan insufficient responder was defined as a participant who met any of the following criteria: (1) currently using a triptan or had used a triptan in the past 6 months, and on the occasions that a triptan dose was taken, had not achieved pain freedom at 2 h post dose on more than half of those occasions; (2) no longer used a triptan due to lack of efficacy; (3) no longer used a triptan due to side effects; (4) never used a triptan due to warnings, precautions, or contraindications

dRecorded at time of randomization

Pooled Efficacy Outcomes

The percentage of participants who reported pain freedom at 2 h post initial dose was significantly greater in the pooled ubrogepant 50 mg group (20.5%, n/N = 182/886) compared with placebo (13.0%, 119/912; OR 1.72; 95% CI 1.34, 2.22; P < 0.001) (Fig. 2a). The percentage of participants who reported absence of the most bothersome migraine-associated symptom at 2 h was significantly greater with ubrogepant 50 mg (38.7%, 342/883) than with placebo (27.6%, 251/910; OR 1.68; 95% CI 1.37, 2.05; P < 0.001) (Fig. 2b). Compared with placebo, significantly greater proportions of ubrogepant-treated participants achieved pain relief at 2 h (placebo: 48.7%, 444/912; ubrogepant 50 mg: 61.7%, 547/886; OR 1.73; 95% CI 1.42, 2.10; P < 0.001) (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 2.

Pooled efficacy results. Percentage of participants reporting pain freedom (a) and absence of the most bothersome migraine-associated symptom (b) at 2 h post dose in the pooled placebo and pooled ubrogepant 50 mg groups from ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II

Fig. 3.

Pooled efficacy results. Percentage of participants reporting pain relief at 2 h post dose (a) and the rate of sustained pain relief from 2 to 24 h and 2 to 48 h post dose (b) in the pooled placebo and pooled ubrogepant 50 mg groups from ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II

Both pain freedom and pain relief rates were captured up to 48 h post dose. Significantly more ubrogepant-treated participants reported sustained pain freedom from 2 to 24 h post initial dose (13.6%, n/N = 119/875) than those in the placebo group (8.4%, 76/903; OR 1.71; 95% CI 1.26, 2.32; P < 0.001). The rate of sustained pain freedom from 2 to 48 h post initial dose was also significantly higher in the pooled ubrogepant group (11.1%, 96/863) than in the placebo group (6.6%, 59/894; OR 1.76; 95% CI 1.26, 2.48; P = 0.001). Sustained pain relief from 2 to 24 h post initial dose was obtained in significantly more ubrogepant-treated participants (36.5%, 315/862) than in patients receiving placebo (20.9%, 186/890; OR 2.20; 95% CI 1.77, 2.74; P < 0.001), as was sustained pain relief from 2 to 48 h post initial dose (ubrogepant 50 mg: 31.4%, 260/829; placebo: 17.7%, 154/871; OR 2.14; 95% CI 1.70, 2.69; P < 0.001; Fig. 3b).

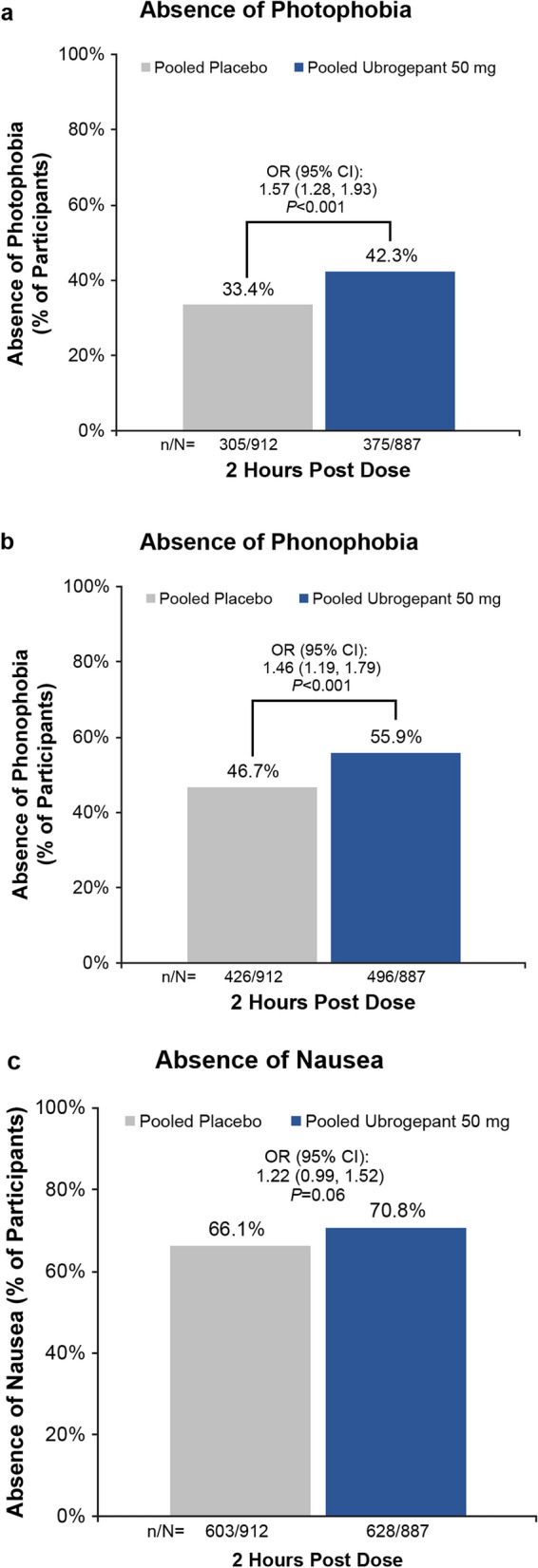

Significantly larger proportions of ubrogepant-treated than placebo-treated participants reported absence of photophobia (OR 1.57; 95% CI 1.28, 1.93; P < 0.001) and phonophobia (OR 1.46; 95% CI 1.19, 1.79; P < 0.001) at 2 h post dose, but not absence of nausea at 2 h post dose (OR 1.22; 95% CI 0.99, 1.52; P = 0.06) (Fig. 4a–c).

Fig. 4.

Absence of migraine-associated symptoms at 2 h post dose. Percentage of participants reporting absence of photophobia (a), phonophobia (b), and nausea (c) in the pooled placebo (n = 912) and pooled ubrogepant 50 mg (n = 887) groups from ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II

In the pooled ubrogepant 50 mg mITT population, 39.8% (n/N = 353/887) of participants opted to take a second dose of study medication 2–48 h after the initial dose, compared with 44.8% (409/912) of participants in the placebo group. Among ubrogepant 50 mg participants who took a second dose, rates of pain freedom were significantly greater in participants who were randomized to a second dose of ubrogepant 50 mg (34.0%, 53/156) than in those who were randomized to placebo as their second administration (19.1%, 25/131; OR 2.20; 95% CI 1.26, 3.85; P = 0.005; Fig. 5). For those who reached pain relief at 2 h after the initial dose, a greater proportion of participants achieved pain freedom at 2 h after the second ubrogepant 50 mg dose (54.7%, 41/75) compared with those who took ubrogepant 50 mg for the initial dose and placebo for the second dose (33.3%, 19/57; OR 2.64, 95% CI 1.27, 5.49; P = 0.009).

Fig. 5.

Efficacy of a second dose. Percentage of participants reporting pain freedom 2 h after a second dose of ubrogepant 50 mg versus placebo in the 353 participants in the pooled ubrogepant 50 mg group who opted to take a second dose of study medication

Adverse Events and Tolerability

Within 48 h of the initial or the optional second dose, treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) were reported by 11.5% (113/984) of participants in the pooled placebo group and by 11.2% (107/954) in the pooled ubrogepant 50 mg group. The most common TEAE was nausea, which occurred in less than 2% in each pooled group (Table 2). Treatment-related TEAEs occurred in the same percentage of participants (7.2%) in the pooled placebo group and the pooled ubrogepant 50 mg group during the 48-h post-dose time frame. No serious AEs (SAEs) occurred within 48 h after any dose. Among participants who took an optional second dose of study medication, the rates of TEAEs occurring within 48 h post initial or second dose were similar in those who took placebo for the first and second doses (12.1%, n/N = 54/446), those who took ubrogepant 50 mg followed by placebo (10.7%, 19/178), and in participants who took ubrogepant 50 mg for the initial and second doses (12.2%, 24/196).

Table 2.

Overall summary of adverse events

| Adverse events | No. (%) of participants | |

|---|---|---|

| Pooled placebo (n = 984) | Pooled ubrogepant 50 mg (n = 954) | |

| Occurring within 48 h after initial or optional second dose | ||

| ≥ 1 TEAE | 113 (11.5) | 107 (11.2) |

| TEAEs in ≥ 2% of participants in any groupa | ||

| Nausea | 18 (1.8) | 18 (1.9) |

| Dizziness | 11 (1.1) | 11 (1.2) |

| Somnolence | 6 (0.6) | 7 (0.7) |

| Dry mouth | 8 (0.8) | 4 (0.4) |

| Treatment-related TEAE | 71 (7.2) | 69 (7.2) |

| Treatment-related TEAEs in ≥ 2% of participants in any groupa | ||

| Nausea | 17 (1.7) | 16 (1.7) |

| Somnolence | 6 (0.6) | 6 (0.6) |

| Serious adverse event | 0 | 0 |

| Occurring within 30 days after any dose | ||

| ≥ 1 TEAE | 225 (22.9) | 259 (27.1) |

| TEAEs in ≥ 2% of participants in any groupa | ||

| Nausea | 22 (2.2) | 21 (2.2) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 17 (1.7) | 18 (1.9) |

| Dizziness | 14 (1.4) | 18 (1.9) |

| Somnolence | 6 (0.6) | 8 (0.8) |

| Dry mouth | 9 (0.9) | 4 (0.4) |

| Treatment-related TEAE | 88 (8.9) | 90 (9.4) |

| Treatment-related TEAEs in ≥ 2% of participants in any groupa | ||

| Nausea | 19 (1.9) | 18 (1.9) |

| Somnolence | 6 (0.6) | 7 (0.7) |

| Serious adverse event | 0 | 3 (0.3) |

TEAE Treatment-emergent adverse event

aEvents reported by ≥ 2% of all participants in any treatment group (including ubrogepant 25 mg and 100 mg groups (see ESM Table S1) of ACHIEVE I and II

Within 30 days after any dose, 22.9% (225/984) of participants in the pooled placebo group and 27.1% (259/954) in the pooled ubrogepant 50 mg group reported TEAEs (Table 2). Nausea was the most common TEAE during this period, occurring in 2.2% of participants in each pooled group. Treatment-related TEAEs were reported in 8.9% (88/984) and 9.4% (90/954) of participants in the pooled placebo and ubrogepant 50 mg groups, respectively. No individual treatment-related TEAE was reported in more than 2% of participants in either pooled group. Three (0.3%) participants in the pooled ubrogepant 50 mg group and none in the pooled placebo group had an SAE (pericardial effusion, appendicitis, or spontaneous abortion). None of these SAEs was considered to be treatment related. No deaths or discontinuations due to an AE were reported. The types and frequencies of AEs were similar in the 25 mg and 100 mg dose groups in the individual trials compared with the pooled groups (ESM Table S1). No safety concerns were identified based on laboratory, ECG, and vital sign results. Monitoring of hepatic laboratory values showed no clinically relevant signs of hepatotoxicity. There were no AEs of clinical interest related to suicidal intent or behavior.

Discussion

The results of this pooled analysis of two pivotal clinical trials further support the role of ubrogepant, a novel CGRP receptor antagonist, as an effective and well tolerated acute treatment of migraine attacks in adults. Compared with placebo, significantly greater proportions of participants who took ubrogepant 50 mg achieved pain relief, pain freedom, and absence of photophobia and phonophobia at 2 h after initial dosing. These treatment effects for pain freedom and pain relief were sustained from 2 to 48 h post dose. Among ubrogepant-randomized participants who opted to take a second dose of study medication, a second dose of ubrogepant 50 mg was associated with significantly greater rates of pain freedom and absence of most bothersome migraine-associated symptom compared with those who received placebo for their second dose of study medication. Overall, these data are consistent with the results from the individual ACHIEVE trials [18, 19].

The pooled analysis of tolerability and safety data identified no new safety concerns for ubrogepant. In this pooled sample of nearly 1800 participants, the rates and patterns of TEAEs were broadly similar for the ubrogepant 50 mg and the placebo groups, regardless of whether the participant took an optional second dose. Nausea was the most common TEAE, occurring in less than 2% of the pooled sample. No clinically relevant adverse cardiac or hepatic effects were reported. No treatment-related SAEs occurred.

While both ACHIEVE trials were short-term, single-attack trials, the long-term safety of intermittent use of ubrogepant has been evaluated in an open-label 52-week extension trial. In this extension trial, participants who completed one of the ACHIEVE trials were re-randomized 1:1:1 to ubrogepant 50 mg (n = 404), ubrogepant 100 mg (n = 409), or usual care (i.e., the acute medication they had been taking before entering the trial; n = 417) [22]. Over the 1-year extension trial, during which more than 21,000 attacks were treated with ubrogepant, the incidence of treatment-related TEAEs was low (10–11% of ubrogepant-treated participants) and no hepatic or cardiovascular (CV) safety issues were noted. Overall, these results support the tolerability and safety of ubrogepant over long-term repeated use for the acute treatment of migraine.

Commonly prescribed acute medications for migraine, such as triptans, ergot derivatives, and NSAIDs, have a number of CV contraindications or precautions that prevent or limit their use in a portion of the migraine population [11, 23, 24]. In addition, NSAIDs may cause serious gastrointestinal (GI) side effects, and their use may be limited in people with existing GI comorbidity [25]. An analysis of commercial insurance claims in the USA in 2017 estimated that 13.5% of migraine patients had a CV disease listed as a contraindication in triptan labels, 8.5% had an “other significant underlying CV disease” judged to be a potential contraindication by an expert panel, and an additional 19.8% had at least two CV risk factors identified as warnings to triptans [26]. Together, an estimated 42% of migraine patients had a CV disease contraindicating the use of triptans, or had multiple CV risk factors identified as warnings to triptans [26]. Ubrogepant was not associated with any vasoconstrictor effects when administered at therapeutic concentrations in a preclinical study in human coronary arteries [27]. The favorable efficacy and tolerability/safety profiles of ubrogepant in clinical trials suggest that it may be a useful treatment option for patients with contraindications to other treatments.

A separate analysis of data from the ACHIEVE trials [28] categorized participants as having moderate to high, low, or no CV risk factors at baseline using an algorithm based on the National Cholesterol Education Program [29]. Of the 2901 participants in the pooled safety population, 11% were categorized as having moderate to high CV risk, 32% as having low CV risk, and 58% as having no CV risk factors. The incidence of AEs in the ubrogepant treatment groups was comparable across CV risk categories and did not differ greatly from that in the placebo group. There were no treatment-related CV SAEs in any participant, and the rate of AEs in the Cardiac Disorder System Organ Class (e.g., palpitations) was low and similar in the ubrogepant and placebo treatment groups. Furthermore, a separate analysis of ACHIEVE data compared the efficacy of ubrogepant across subgroups based on self-reported historical triptan response (e.g., triptan-insufficient responders, triptan responders, and triptan naive) [30]. Results of this analysis found that the efficacy of ubrogepant was not significantly impacted by a participant’s previous triptan experience. Additionally, ubrogepant showed significant efficacy in participants who were designated as insufficient responders to triptans based on lack of efficacy, poor tolerability, or never used a triptan due to warnings, precautions, or contraindications. Taken together, these data suggest ubrogepant may provide an important treatment option for those with contraindications to triptans or NSAID use.

This pooled analysis of the ACHIEVE trials has several strengths and limitations. The similarity in trial designs allowed for the data from nearly 1000 participants treated with ubrogepant 50 mg (the only dose evaluated in both trials) to be combined, improving the power to estimate treatment effects and to detect potential safety signals. In this combined population, efficacy results are consistent with those of previous reports, and the pooled safety results demonstrate that no new safety signals emerged in this larger population [18, 19]. The ACHIEVE trials, however, did not include an active comparator and, as single-attack trials, consistency of efficacy and safety and tolerability across multiple attacks could not be evaluated. However, the safety of ubrogepant to treat up to eight migraine attacks every 4 weeks was evaluated in the 52-week extension trial described above, where no negative impact of repeated use was observed on either safety or efficacy of ubrogepant [22]. People with clinically significant CV and GI conditions associated with precautions in the use of triptans or NSAIDs were not included in the ACHIEVE trials, and future studies evaluating the tolerability and safety in these patient populations are necessary.

Conclusions

Pooled analysis of the 50 mg ubrogepant and placebo groups from the pivotal ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II trials demonstrated significant improvements in pain relief, pain freedom, photophobia, and phonophobia with ubrogepant compared with placebo. Overall, ubrogepant 50 mg was well tolerated, with no new safety concerns identified from the larger, pooled ACHIEVE I and II trial data. These results further support ubrogepant as a well-tolerated, safe, and effective acute treatment of migraine with or without aura in adults.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the study participants and all those involved in analyzing the data.

Funding

This study and the Rapid Service Fee for submission were sponsored by Allergan (prior to its acquisition by AbbVie).

Medical writing and/or Editorial Assistance

Writing and editorial assistance was provided to the authors by Lela Creutz, PhD, and Cory R. Hussar, PhD, of Peloton Advantage, LLC, an OPEN Health company, Parsippany, NJ, and was funded by AbbVie.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Prior Presentation

This manuscript is based in part on work that has been previously presented at the American Headache Society 61st Annual Scientific Meeting, July 11–14, 2019; 19th Congress of the International Headache Society, September 5–8, 2019; 13th Annual Headache Cooperative of the Pacific, January 24–25, 2020; the Diamond Headache Clinic Research & Educational Foundation’s 2020 Meeting, February 14–17, 2020; the American Headache Society Virtual Annual Scientific Meeting, June 2020; 72nd Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology, April 25–May 1, 2020 (virtual); the American Headache Society Virtual Annual Scientific Meeting, June 13, 2020; AANPconnect: An Online Conference Experience, September 10–December 31, 2020; and the American Academy of Family Physicians FMX Family Medicine Experience, October 13–17, 2020 (virtual).

Disclosures

Susan Hutchinson has served on advisory boards for AbbVie, Alder, Amgen, Avanir, Biohaven, electroCore, Eli Lilly, Supernus, Theranica, Teva, and Upsher-Smith. She is on the speakers bureau for AbbVie, Amgen, Avanir, electroCore, Eli Lilly, Promius, Supernus, and Teva. David W. Dodick reports the following conflicts within the past 12 months: consulting: AbbVie, AEON, Amgen, Clexio, Cerecin, Cooltech, Ctrl M, Alder, Biohaven, Linpharma, Lundbeck, Promius, Eli Lilly, eNeura, Novartis, Impel, Satsuma, Theranica, WL Gore, Nocira, XoC, Zosano, Upjohn (Division of Pfizer), Pieris, Praxis, Revance, Equinox; honoraria: CME Outfitters, Curry Rockefeller Group, DeepBench, Global Access Meetings, KLJ Associates, Academy for Continued Healthcare Learning, Majallin LLC, Medlogix Communications, MJH Lifesciences, Miller Medical Communications, Southern Headache Society (MAHEC), WebMD Health/Medscape, Wolters Kluwer, Oxford University Press, Cambridge University Press; research support: Department of Defense, National Institutes of Health, Henry Jackson Foundation, Sperling Foundation, American Migraine Foundation, Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI); stock options/shareholder/patents/Board of Directors: Ctrl M (options), Aural analytics (options), ExSano (options), Palion (options), Healint (options), Theranica (options), Second Opinion/Mobile Health (options), Epien (options/Board), Nocira (options), Matterhorn (shares/board), Ontologics (shares/board), King-Devick Technologies (options/board), Precon Health (options/board); patent 17189376.1-1466:vTitle: Botulinum Toxin Dosage Regimen for Chronic Migraine Prophylaxis. Christina Treppendahl has served on advisory boards/speaker bureaus for AbbVie, Alder, Amgen/Novartis, Avanir Pharmaceuticals, Biohaven, Depomed Inc, electroCore, Eli Iroko Pharmaceuticals, Lilly, Impax Labs, Impel NeuroPharma, the National Headache Foundation, Pernix, Promius Pharma, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, Upsher-Smith Laboratories, Zogenix, and Zosano Pharma. She has served as Principal Investigator for clinical trials including AbbVie, Alder, Avanir, electroCore, Novartis, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Teva, and Theranica. Nathan L. Bennett has completed clinical research for AbbVie, Amgen, Avanir, electroCore, Impax, Lilly, and Teva; has consulted or acted on an advisory board for AbbVie, Amgen, Lilly, Pernix, Promius, and Supernus; and has been a speaker for AbbVie, Amgen, Avanir, Promius, Supernus, and Teva. Sung Yun Yu, Hua Guo, and Joel M. Trugman are employees of AbbVie, and may hold AbbVie stock.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II trials were conducted in conformance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments, or the laws and regulations of the country in which the research was conducted, whichever afforded the greater protection to the individual. Trial protocols were approved by each individual research center’s institutional review board. All participants provided written informed consent before initiation of trial procedures.

Data Availability

AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymized, individual and trial-level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (e.g., protocols and Clinical Study Reports), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications

This clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). Data requests can be submitted at any time and the data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process, or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://www.abbvie.com/our-science/clinical-trials/clinical-trials-data-and-information-sharing/data-and-information-sharing-with-qualified-researchers.html

References

- 1.Silberstein SD. Migraine. Lancet. 2004;363(9406):381–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Silberstein SD. Practice parameter: evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2000;55(6):754–762. doi: 10.1212/WNL.55.6.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silberstein SD. Preventive migraine treatment. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2015;21(4 Headache):973–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Becker WJ. Acute migraine treatment in adults. Headache. 2015;55(6):778–793. doi: 10.1111/head.12550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marmura MJ, Silberstein SD, Schwedt TJ. The acute treatment of migraine in adults: the American Headache Society evidence assessment of migraine pharmacotherapies. Headache. 2015;55(1):3–20. doi: 10.1111/head.12499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bigal M, Rapoport A, Aurora S, Sheftell F, Tepper S, Dahlof C. Satisfaction with current migraine therapy: experience from 3 centers in US and Sweden. Headache. 2007;47(4):475–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malik SN, Hopkins M, Young WB, Silberstein SD. Acute migraine treatment: patterns of use and satisfaction in a clinical population. Headache. 2006;46(5):773–780. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wells RE, Markowitz SY, Baron EP, et al. Identifying the factors underlying discontinuation of triptans. Headache. 2014;54(2):278–289. doi: 10.1111/head.12198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams GS. Triptan use and discontinuation: results from the MAST study. Neurol Rev. 2018;26(8):30. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marcus SC, Shewale AR, Silberstein SD, et al. Triptan discontinuation and treatment patterns among migraine patients initiating triptan treatment in a US commercially insured population (S59.003) [abstract]. Neurology. 2019;92(15 Suppl).

- 11.Drug Safety Communication: FDA strengthens warning that non-aspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can cause heart attacks or strokes. Silver Spring: US Food and Drug Administration; 2015. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-fda-strengthens-warning-non-aspirin-nonsteroidal-anti-inflammatory.

- 12.Lipton RB, Buse DC, Serrano D, Holland S, Reed ML. Examination of unmet treatment needs among persons with episodic migraine: results of the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study. Headache. 2013;53(8):1300–1311. doi: 10.1111/head.12154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lipton RB, Reed ML, Kurth T, Fanning KM, Buse DC. Framingham-based cardiovascular risk estimates among people with episodic migraine in the US population: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study. Headache. 2017;57(10):1507–1521. doi: 10.1111/head.13179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bigal ME, Serrano D, Buse D, Scher A, Stewart WF, Lipton RB. Acute migraine medications and evolution from episodic to chronic migraine: a longitudinal population-based study. Headache. 2008;48(8):1157–1168. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1):1–211. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Burch RC, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Migraine: epidemiology, burden, and comorbidity. Neurol Clin. 2019;37(4):631–649. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2019.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allergan. Ubrelvy. Package insert. Madison: Allergan USA, Inc.; 2020.

- 18.Dodick DW, Lipton RB, Ailani J, et al. Ubrogepant for the treatment of migraine. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(23):2230–2241. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1813049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lipton RB, Dodick DW, Ailani J, et al. Effect of ubrogepant versus placebo on pain and the most bothersome associated symptom in the acute treatment of migraine: the ACHIEVE II randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322(19):1887–1898. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.16711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dodick DW, Lipton RB, Ailani J, et al. Ubrogepant, an acute treatment for migraine, improved patient-reported functional disability and satisfaction in 2 single-attack phase 3 randomized trials. ACHIEVE I and II Headache. 2020;60(4):686–700. doi: 10.1111/head.13766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33(9):629–808. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Ailani J, Lipton RB, Hutchinson S, Knievel K, Lu K, Butler M, et al. Long-term safety evaluation of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine: phase 3, randomized, 52-week extension trial. Headache. 2020;60(1):141–152. doi: 10.1111/head.13682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.GlaxoSmithKline. Imitrex. Package insert. Research Triangle Park: GlaxoSmithKline; 2017.

- 24.Valeant Pharmaceuticals. Migranal. Package insert. Bridgewater: Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America; 2019.

- 25.American Headache Society The American Headache Society position statement on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache. 2019;59(1):1–18. doi: 10.1111/head.13456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dodick DW, Shewale AS, Lipton RB, et al. (eds). Operationalization of triptan labels to identify migraine patients with cardiovascular contraindications and warnings using real-world claims data [poster]. Annual Meeting for the American Headache Society; 4–7 June 2020; San Diego.

- 27.Rubio-Beltran E, Chan KY, van den Bogaerdt A, et al. (eds) Characterization of the effects of the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonists, atogepant and ubrogepant, on isolated human coronary, cerebral, and middle meningeal arteries [abstract]. Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology; 4–10 May 2019; Philadelphia.

- 28.Hutchinson S, Silberstein SD, Blumenfeld AM, Lipton RB, Lu K, Yu S, et al. Safety of ubrogepant in participants with moderate to high cardiovascular risk [abstract P124] Headache. 2019;59(suppl 1):104–105. [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Cholesterol Education Program. Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (ATP III). JAMA. 2001;285(19):2486–97. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Blumenfeld AM, Goadsby PJ, Dodick DW, Hutchinson S, Liu C, Finnegan M, et al. Ubrogepant is effective for the acute treatment of migraine in patients with an insufficient response to triptans [abstract]. Neurology. 2019;92(15 Suppl):P3.10–024.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymized, individual and trial-level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (e.g., protocols and Clinical Study Reports), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications

This clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). Data requests can be submitted at any time and the data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process, or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://www.abbvie.com/our-science/clinical-trials/clinical-trials-data-and-information-sharing/data-and-information-sharing-with-qualified-researchers.html