Abstract

Introduction

Erenumab, a first-in-class monoclonal antibody targeting the calcitonin gene-related peptide pathway, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2018 for the prevention of migraine in adults. There is limited data available on its impact in real-world settings. The study aim was to characterize the real-world treatment profiles, clinical outcomes, and healthcare resource utilization of patients prescribed erenumab from select major US headache centers.

Methods

A retrospective chart review of patients with migraine treated with erenumab for at least 3 months across five major headache centers was conducted. Data was collected from patient charts between April 2019 and April 2020 and included patient and clinical characteristics, migraine medication use, and outpatient visits. The date of the first prescription fill of erenumab was defined as the index date. The baseline period comprised the 3 months prior to the index date and the study period comprised the at least 3 months on erenumab treatment.

Results

Data from a total of 1034 patients with chronic migraine with a mean of 9.3 months of erenumab treatment were analyzed. Patients were on average 48 years old, 86% were female, and 79% were white. Patients had a mean of 5 preventive treatment failures prior to erenumab initiation. Patients used a mean of 2 preventive treatments (excluding erenumab) and 2 acute treatments during baseline and study periods. Among patients with effectiveness data, 45% of patients had improvement in physician-reported migraine severity and 35% experienced at least 50% reduction in mean headache/migraine days per month. The average number of monthly outpatient visits was 0.43 and 0.30 before and after erenumab initiation, respectively.

Conclusion

In this predominantly refractory chronic migraine population treated in select headache centers, patients had fewer headache/migraine days per month and outpatient visits after initiating erenumab. However, patients largely continued to be managed via a polypharmacy approach after erenumab initiation.

Keywords: Effectiveness, Erenumab, Healthcare resource utilization, Migraine, Real world, Treatment profiles

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Erenumab, a first-in-class monoclonal antibody targeting the calcitonin gene-related peptide pathway, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2018 for the prevention of migraine in adults. |

| Given the limited data available on its impact in real-world settings, it is important to characterize the real-world treatment profiles, clinical outcomes, and healthcare resource utilization of patients prescribed erenumab from US headache centers. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| The real-world evidence presented in this study supports previous clinical findings of the benefit of erenumab in the management of chronic migraine, including a reduction in the monthly frequency of headache/migraine in a predominantly refractory population (multiple preventive treatment failures). |

| Despite the demonstrated effectiveness of erenumab, patients treated in the US headache centers largely continued to be managed via a polypharmacy approach in the initial months after erenumab initiation. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14222975.

Introduction

Migraine is a neurological disorder that is characterized by recurrent episodes of moderate–severe headache, often associated with nausea, phonophobia, photophobia, and/or other sensory dysfunction [1]. The 1-year prevalence of migraine in the USA is 12% [2]. Migraine has been shown to be associated with reduced quality of life, functional impairment, reduced productivity, and high economic burden, highlighting the importance of having effective therapeutic strategies [3–7].

Clinical management of migraine can be preventive and/or acute, with the goals of reducing overall attack frequency, severity, duration, and disability for the former, versus relief of pain and associated symptoms of a migraine attack for the latter [8]. Because of the heterogeneity of migraine characteristics and symptom profiles amongst patients, optimizing individualized treatment programs is challenging. Treatment guidelines recommend the use of preventive treatment in patients with migraine on the basis of severity and frequency of attacks, adverse events or failure of acute treatments, and/or patient preference [8]. Many of the available preventive therapies were not developed specifically for migraine and have limited efficacy and tolerability [8]. Earlier preventive medication options included non-specific therapies (such as repurposed antiepileptic drugs, antihypertensives, antidepressants, and botulinum toxins) [8]. More recently, monoclonal antibodies targeting the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) pathway were developed specifically for migraine and are now available for the preventive treatment of migraine in adults. Of these, erenumab (erenumab-aooe in the USA) was the first anti-CGRP pathway therapy to be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in May 2018, representing the first mechanism-based and disease-specific preventive treatment for migraine [8, 9]. Since the initial approval of erenumab, three monoclonal antibodies targeting the CGRP ligand were subsequently approved by the FDA for the preventive treatment of migraine in adults (galcanezumab, fremanezumab, and eptinezumab) [10–12].

Clinical trials demonstrated that 3 months of erenumab treatment resulted in an absolute reduction of 2–7 monthly migraine days from baseline, or 1–2.5 fewer monthly migraine days relative to placebo, in patients with episodic or chronic migraine, among other benefits [13–15]. Given the recent approval of erenumab, there is limited data available on its impact in real-world settings. A few studies have evaluated the use of erenumab in clinical practice, but they have been conducted at single centers with limited sample sizes [16–18] or in multiple centers outside of the USA [19, 20]. Therefore, this study aimed to characterize the real-world treatment profiles, clinical outcomes, and healthcare resource utilization (HRU) of patients prescribed erenumab from select major US headache centers.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

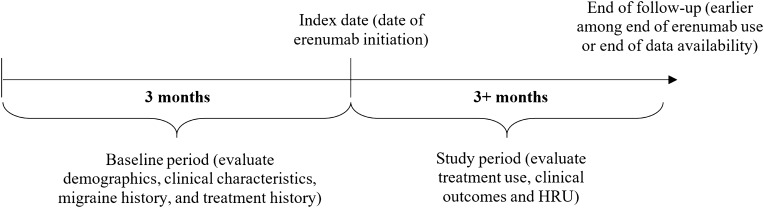

This was a center-based, retrospective chart review of patients with migraine treated at five major US headache centers which were geographically dispersed, conducted from April 2019 to April 2020. The date of the first prescription fill of erenumab was defined as the index date (Fig. 1). The baseline period comprised the 3 months prior to the index date, while the study period comprised the index date to the earliest of erenumab discontinuation (at least 3 months), end of data availability, or death.

Fig. 1.

Study design scheme. HRU healthcare resource utilization

Patients were included in the study if they met the following eligibility criteria: (1) were diagnosed with migraine (chronic or episodic, as indicated in the patient chart); (2) initiated erenumab after its US approval date (May 17, 2018) and were treated with erenumab for at least 3 consecutive months; (3) were aged 18 years or more as of the index date; (4) had available disease, treatment, and healthcare resource use history for the 3 months before and after the index date; and (5) were not treated with erenumab or another anti-CGRP agent in a clinical trial setting.

Treating physicians extracted information from patient charts using an electronic case report form (eCRF). All data were extracted from existing medical records and de-identified. Ethics review was conducted by individual centers with an internal review process. For Cleveland Clinic participation, expedited ethics review was approved by Cleveland Clinic IRB (IRB# 19-614), which has an internal review process. New England Institutional Review Board exemption (IRB# 120190088) was received for the remaining centers.

Data Collected and Statistical Analyses

Data collected from the 1103 patient charts included information on patient characteristics, erenumab use, effectiveness and safety, preventive and acute migraine treatments, and HRU. Outcomes related to erenumab use included dose changes and discontinuation patterns. Effectiveness and clinical outcomes included migraine severity, headache/migraine days per month, headache/migraine duration, proportion of patients with migraine with aura or menstrual-related migraine, Migraine Disability Assessment Test (MIDAS) or modified MIDAS scores, and Headache Impact Test (HIT-6™) scores. Treatment data included the types and number of preventive and acute migraine treatments, as well as initiation and discontinuation patterns. HRU was reported as the number of outpatient visits per month and the proportion of outpatient visits with a neurologist. Reporting of constipation in patient charts was collected as a potential safety outcome of interest.

Additionally, physician interviews were conducted as semi-structured interviews with principal investigators from four of the participating centers to gain additional insights into the results from the chart review study, as highlighted in the “Discussion” section. In particular, insights were gathered on perspectives and perceptions in real-world clinical practice settings regarding the clinical effectiveness of erenumab, as well as the perspectives and diagnostic decision-making involved in the charting of constipation, an adverse event associated with erenumab [21].

All analyses were descriptive in nature and no statistical inference was performed. Continuous variables were described using means, standard deviations (SDs), and medians, while categorical variables were described using frequencies and proportions. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

After data abstraction, only 6% of included patients had episodic migraine (n = 69); therefore, results for patients with chronic migraine are reported herein.

Patient Characteristics

A total of 1034 patients with chronic migraine were included in the study. The mean age was 48 years, 893 (86%) were female, and 814 (79%) were white (Table 1). The majority of patients were from the Central/Midwest region (39%), followed by the West (26%), Northeast (24%), and South (10%). The most common comorbidities included behavioral nervous system disorders (53%; e.g., depression [31%], anxiety [29%], sleep disorders [20%]), seasonal allergy (26%), and cardiovascular diseases (19%; e.g., hypertension [14%], hyperlipidemia [7%]).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics as of erenumab initiation

| Patients with chronic migraine (N = 1034) | |

|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Age (years), mean ± SD [median] | 47.56 ± 12.92 [48] |

| Female, N (%) | 893 (86.4%) |

| Race/ethnicity, N (%) | |

| White | 814 (78.7%) |

| Black or African American | 22 (2.1%) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (0.1%) |

| Asian | 8 (0.8%) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 1 (0.1%) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 32 (3.1%) |

| Other | 42 (4.1%) |

| Unknown/not sure | 123 (11.9%) |

| Geographic region, N (%) | |

| Northeast | 247 (23.9%) |

| Central/Midwest | 404 (39.1%) |

| South | 108 (10.4%) |

| West | 273 (26.4%) |

| Unknown/not sure | 2 (0.2%) |

| Background characteristics | |

| Body mass index (BMI), N (%) | |

| < 18.5 | 23 (2.2%) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 230 (22.2%) |

| 25.0–29.9 | 223 (21.6%) |

| ≥ 30.0 | 275 (26.6%) |

| Unknown/not sure | 283 (27.4%) |

| Comorbidities with prevalence ≥ 10%, N (%) | |

| Behavioral nervous system disorders | 544 (52.6%) |

| Depression | 317 (30.7%) |

| Anxiety | 303 (29.3%) |

| Sleep disorder | 208 (20.1%) |

| Allergy (seasonal) | 273 (26.4%) |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 192 (18.6%) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 69 (6.7%) |

| Hypertension | 141 (13.6%) |

| Asthma | 110 (10.6%) |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| History of medication overuse,a N (%) | 301 (29.1%) |

| Medication overuse resulted in headache | 201 (66.8%) |

| Medication overuse did not result in headache | 94 (31.2%) |

SD standard deviation, BMI body mass index

aHistory of medication overuse and medication overuse headache were reported for a patient’s lifetime management of migraine prior to erenumab initiation and was not strictly limited to the baseline period

Prior to erenumab initiation, patients averaged 8.8 years of disease duration (median 5 years) from either migraine diagnosis or onset, depending on data available in patient charts (Table 2). Among 301 (29%) patients with a history of medication overuse as assessed by the physician, the majority (67%) experienced medication overuse headache (Table 1).

Table 2.

Erenumab use during the study period

| Patients with chronic migraine (N = 1034) | |

|---|---|

| Time from migraine diagnosis/onset to erenumab initiation (years), mean ± SD [median] | 8.82 ± 10.59 [5] |

| Time on treatment (months), mean ± SD [median] | 9.33 ± 3.83 [9] |

| Dose used at initiation, N (%) | |

| 70 mg | 793 (76.7%) |

| 140 mg | 241 (23.3%) |

| Dose escalation,a N (%) | 572 (72.1%) |

| Dose reduction,b N (%) | 9 (3.7%) |

| Erenumab use by the end of the study period, N (%) | |

| Persistence | 790 (76.4%) |

| Discontinuation | 244 (23.6%) |

| Time on treatment among those who discontinued (months),c mean ± SD [median] | 7.32 ± 3.11 [7] |

| Reason for discontinuation,d N (%) | N = 244 |

| Availability of other treatments | 10 (4.1%) |

| Cost | 12 (4.9%) |

| Insurance reimbursement | 36 (14.8%) |

| Non-response or lack of effectiveness | 121 (49.6%) |

| Patient assistance program stopped | 1 (0.4%) |

| Patient preference | 11 (4.5%) |

| Tolerability/adverse event | 45 (18.4%) |

SD standard deviation

aDose escalation was reported among patients whose dose at erenumab initiation was 70 mg

bDose reduction was reported among patients whose dose at erenumab initiation was 140 mg

cTime on treatment was reported among patients who discontinued erenumab. Note that to be eligible for the study, patients must be treated with erenumab for at least 3 consecutive months

dReasons for discontinuation are not mutually exclusive, so one patient may have more than one response

Erenumab Use

The study period covered a mean of 9.3 months of erenumab treatment (median 9 months) (Table 2). Among 793 (77%) patients who initiated erenumab at 70 mg, 572 (72%) patients later escalated to 140 mg. Among 241 (23%) patients who initiated at 140 mg, only 9 (4%) reduced their dose. By the end of the study period, 790 (76%) patients persisted on erenumab. Among the 244 patients who discontinued erenumab, the mean time on treatment was 7.3 months, and the most common reasons for discontinuation were non-response or lack of effectiveness (121 patients, 50%), tolerability/adverse events (45 patients, 18%), and insurance reimbursement (36 patients, 15%).

Treatment Patterns

The majority of patients had experienced several migraine preventive treatment failures prior to erenumab initiation (mean of 5 and median of 4 preventive treatment failures [as assessed by the physicians]). At baseline, the most commonly prescribed migraine preventive treatments were antiepileptics (49%), antidepressants (48%), and botulinum toxin (42%), while the most commonly prescribed acute treatments were triptans (69%), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; 40%), and muscle relaxants (28%; Table 3).

Table 3.

Preventive and acute migraine-related treatment patterns during the baseline and study periods

| Patients with chronic migraine (N = 1034) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Baseline period | Study period | |

| Number of prior preventive treatment failures,a mean ± SD [median] | 5.20 ± 4.49 [4] | – |

| Number of preventive treatments,b,c mean ± SD [median] | 2.00 ± 1.34 [2] | 2.02 ± 1.36 [2] |

| Number of acute treatments,d mean ± SD [median] | 2.00 ± 1.43 [2] | 2.25 ± 1.63 [2] |

| Initiation of new preventive treatment during study period,c N (%) | – | 160 (15.5%) |

| Initiation of new acute treatment during study period,d N (%) | – | 250 (24.3%) |

| Discontinuation of preventive treatment from baseline,e N (%) | – | 300 (32.8%) |

| Discontinuation of acute treatment from baseline,f N (%) | – | 250 (27.0%) |

| Most commonly reported preventive treatment types, N (%) | ||

| Antiepileptic agents | 506 (48.9%) | 501 (48.5%) |

| Antidepressants | 494 (47.8%) | 488 (47.2%) |

| Botulinum toxin | 438 (42.4%) | 427 (41.3%) |

| Antihypertensive agents | 309 (29.9%) | 307 (29.7%) |

| Other migraine preventative agents | 83 (8.0%) | 82 (7.9%) |

| Anti-CGRP (excluding erenumab) | 0 (0.0%) | 39 (3.8%) |

| Most commonly reported acute treatment types, N (%) | ||

| Triptans | 709 (68.6%) | 732 (70.8%) |

| NSAIDs | 409 (39.6%) | 453 (43.8%) |

| Muscle relaxants | 285 (27.6%) | 314 (30.4%) |

| Opioids | 129 (12.5%) | 121 (11.7%) |

| Ergotamines | 65 (6.3%) | 78 (7.5%) |

| Barbiturates | 28 (2.7%) | 33 (3.2%) |

| Other | 11 (1.1%) | 15 (1.5%) |

Anti-CGRP anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide, NSAID non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug

aAssessed at any time prior to erenumab initiation; the number of treatment failures prior to care at participating centers may be underreported

bNumber of preventive treatments excluded erenumab

cAssessed among 1032 patients with treatment information in both baseline and study periods

dAssessed among 1027 patients with treatment information in both baseline and study periods

eAssessed among 916 patients with known discontinuation status of baseline treatments

fAssessed among 925 patients with known discontinuation status of baseline treatments

The number of concomitant migraine preventive and acute therapies remained similar from the baseline to study period, although discontinuation and initiation of concomitant treatments were noted (Table 3). During the baseline and study periods, patients used a mean of 2 preventive treatments (other than erenumab) and a mean of 2 acute treatments. Among 1032 patients with preventive treatment information in both the baseline and study periods, 160 (16%) patients initiated new preventive treatments (other than erenumab) during the study period (Table 3). Among 1027 patients with acute treatment information available in both the baseline and study periods, 250 (24%) patients initiated new acute treatments during the study period (Table 3). Additionally, 300 (33% of 916 patients with data available) discontinued at least one preventive baseline treatment, and 250 (27% of 925 patients with data available) discontinued at least one acute baseline treatment (Table 3).

Effectiveness

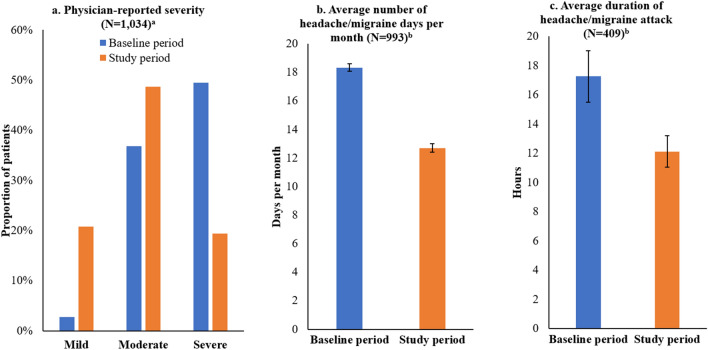

At baseline, 50% of patients had migraine classified as “severe” and 37% had migraine classified as “moderate” on the basis of physician assessment of severity (Fig. 2a). After erenumab initiation, only 19% had migraine classified as “severe” and 49% had migraine classified as “moderate.” Among the 877 (85%) patients with this information available in both baseline and study periods, 397 (45%) improved in severity after erenumab initiation on the basis of physician assessment (Table 4).

Fig. 2.

Headache/migraine characteristics during the baseline and study periods. aUnknown severity not shown. bSample includes patients with data available in both baseline and study period

Table 4.

Effectiveness: change from the baseline period to the study period

| Patients with chronic migraine (N = 1034) | |

|---|---|

| Patients with information for physician-reported severity in the baseline and study periods, N (%) | 877 (84.8%) |

| Patients who improved between the baseline and study period, N (%) | 397 (45.3%) |

| Patients who had no change between the baseline and study period, N (%) | 440 (50.2%) |

| Patients who worsened between the baseline and study period, N (%) | 40 (4.6%) |

| Patients with information for headache/migraine days per month in the baseline and study periods, N (%) | 993 (96.0%) |

| Change in average number of headache/migraine days per month, mean ± SD [median] | − 5.64 ± 7.29 [− 5] |

| Patients with at least 50% reduction in average number of headache/migraine days per month, N (%) | 352 (35.4%) |

| Patients with information for average headache/migraine duration in the baseline and study periods, N (%) | 409 (39.6%) |

| Change in average headache/migraine duration (h), mean ± SD [median] | − 5.14 ± 23.80 [− 2] |

| Patients with information for MIDAS and/or modified MIDAS score in the baseline and study periods, N (%) | 64 (6.2%) |

| Change in MIDAS and/or modified MIDAS score, mean ± SD [median] | − 6.89 ± 20.68 [− 6] |

| Patients with information for HIT-6™ score in the baseline and study periods, N (%) | 151 (14.6%) |

| Change in HIT-6™ score, mean ± SD [median] | − 3.87 ± 11.17 [− 2] |

SD standard deviation, MIDAS Migraine Disability Assessment Test, HIT-6™ Headache Impact Test

Mean headache/migraine days per month decreased by a mean of 5.6 days, from 18.3 days at baseline to 12.7 days during the study period (Table 4, Fig. 2b). Among 993 (96%) patients with this information available in both time periods, 352 (35%) experienced at least 50% reduction in their mean headache/migraine days per month (Table 4).

Headache/migraine duration information was available for 409 (40%) patients during the baseline and study periods. Among these patients, mean duration per attack decreased by a mean of 5.1 h, from 17.3 h at baseline to 12.1 h during the study period (Fig. 2c; Table 4).

Among the 64 (6%) patients with MIDAS and/or modified MIDAS scores recorded in the baseline and study periods, the MIDAS score decreased by a mean of 6.9 points to a mean of 27.6 (Table 4). Among the 151 (15%) patients with HIT-6™ scores in the baseline and study period, the HIT-6™ score decreased by a mean of 3.9 points to a mean of 61.0 (Table 4).

Amongst the entire cohort, the number of patients with report of at least one migraine attack with aura decreased from 100 (10%) in the baseline period to 53 (5%) in the study period. Likewise, the number of female patients with reported menstrual-related migraine decreased from 197 (22%) to 145 (16%) (data not shown).

Reported Constipation

Constipation was recorded in 23 (2%) patient charts prior to erenumab initiation, compared to 216 (21%) during the study period. Of these patients, 48 (22%) were prescribed treatments during the study period other than erenumab that may be potentially associated with constipation. For example, 22 (10%) patients used opioids and 19 (9%) used gabapentin. Other treatments included doxepin, pregabalin, and cyproheptadine (data not shown).

Healthcare Resource Utilization

At baseline, patients averaged 0.43 outpatient visits per month (or approximately 5.2 visits per year) and 84% of these visits were with neurologists (Fig. 3). During the study period, patients averaged 0.30 outpatient visits per month (or approximately 3.6 visits per year) and 80% of these visits were with neurologists.

Fig. 3.

Outpatient visits during the baseline and study periods

Discussion

In this retrospective chart review of patients with chronic migraine treated at headache centers in the USA, the majority of patients were refractory to multiple prior preventive therapies yet experienced fewer headache/migraine days per month and shorter migraine/headache attacks after initiating erenumab. Two recent studies also evaluated the real-world effectiveness of erenumab in clinical practice [17, 18]. In a US chart review and survey-based study of patients with chronic migraine (94% of patients), episodic migraine, or medication overuse headache by Robblee et al., the number of headache/migraine days per month decreased by 6.5–8.4 days between baseline (mean 24.8 days) and 6 months of erenumab treatment (mean 18.3 days) [18]. Additionally, 35% of patients experienced at least 50% reduction in their mean headache days per month and 55% of patients experienced at least 50% reduction in their mean migraine days per month. In a separate prospective evaluation of patients with chronic migraine from a headache center in the UK by Lambru et al., the number of monthly migraine days was reduced by 6.0 (from 19.7 at baseline) following 3 months of erenumab treatment, with 35% of patients achieving at least 50% reduction in their mean migraine days per month [17]. These results are consistent with the current study, which demonstrated a 5.6-day reduction in mean headache/migraine days per month (from 18.3 days), with 35% of patients achieving at least 50% reduction in the mean headache/migraine days per month. Of note, Lambru et al. reported a higher proportion of patients (54%) with medication overuse compared to the current study (29%) [17]. However, Lambru et al. did not rely on chart review data, which may underreport medication overuse (unknown for 16% of patients in the current study). Moreover, patients included in the studies by Robblee et al. and Lambru et al. had a greater number of migraine preventive treatment failures prior to initiating erenumab. Robblee et al. reported a mean 11.2 ineffective oral preventive medications, Lambru et al. reported a mean of 8.4 preventive treatment failures, and the current study a mean of 5 preventive treatment failures [17, 18]. These data support erenumab’s real-world effectiveness even amongst patients who had multiple preventive treatment failures prior to initiation. The results of the current study are also consistent with those from the erenumab clinical trials, which show that 30–50% of patients with chronic or episodic migraine achieve at least 50% reduction in mean migraine days per month after treatment with erenumab for at least 3 months [13–15, 22].

After erenumab initiation, patients largely continued to be managed via a polypharmacy approach, with an average number of 2 acute and 2 preventive treatments, besides erenumab. However, on the basis of perspectives and perceptions from the semi-structured interviews with physicians, tapering and discontinuation of other treatments typically would only occur after patients have achieved a stable response to erenumab, which may be 3–6 months after treatment initiation. Therefore, the current study period may not have fully captured the comprehensive landscape of treatment discontinuation patterns or dose modifications in the average 9 months of follow-up. In addition, concomitant prophylactic treatments like antidepressants, antihypertensives, and antiepileptic agents may be continued or only tapered (rather than discontinued) potentially to treat other comorbid conditions. Of note, more than half of the patients included in this study also suffered from behavioral nervous system disorders (such as depression and anxiety) and nearly 15% had hypertension. These comorbidities have been shown to be risk factors for chronic migraine [23]. Further research is needed to gain a better understanding of migraine treatment patterns and to establish a clear approach to modifying existing migraine treatment profiles after anti-CGRP pathway therapies are initiated.

Although effective in the prevention of migraine, anti-CGRP pathway therapies are also associated with constipation [24]. The physician interviews helped to contextualize the results regarding constipation in the current study and highlighted the need for better tools to measure and assess constipation in a systematic and clinically meaningful way. For instance, regarding documentation of constipation-related information in patient charts, interviewed physicians reported that there was no standardized approach to eliciting, recording, and confirming information related to constipation. Prior to initiating erenumab, multiple physicians reported that patients were not routinely asked about constipation, unless they were prescribed medications (e.g., opioids) that may induce constipation or had comorbidities that were risk factors for constipation (e.g., gastrointestinal disorders). The results of the chart review study showed that only 23 (2%) patients had constipation recorded in their charts prior to erenumab initiation, despite the use of baseline opioids in 129 (13%) patients. This suggests there may be underreporting of constipation in patient charts at baseline, in part from lack of physician inquiry, given an expected constipation rate of 41% among patients with chronic non-cancer pain treated with opioids [25]. Alternatively, these patients may have been treated prophylactically for constipation and therefore did not experience constipation during baseline. The physicians also reported that discontinuation of erenumab because of constipation was uncommon. Half of the physicians reported that only 5–10% of their patients discontinued erenumab because of constipation, while the other half stated that discontinuation related to constipation happened rarely or never. Lambru et al. also reported a similar rate of erenumab discontinuation due to constipation (6%) in their real-world analysis of patients with refractory chronic migraine, which is higher than what has been reported in clinical trials (less than 1% of patients discontinued treatment because of constipation as an adverse event) [15, 17]. Similarly, for only 4% of all patient charts, the reason for erenumab discontinuation was reported as tolerability/adverse event in the current chart review study, though the exact type of adverse event was not specified this study. Although 216 (21%) patients had constipation after erenumab initiation recorded in the patient charts, the details on the severity, duration, or the extent to which it was clinically meaningful was not provided. Therefore, there is a need to better understand the association between severity of constipation and treatment patterns like medication persistence and discontinuation.

This study also assessed the effectiveness of erenumab using patient-reported outcomes (PROs), specifically MIDAS and HIT-6™ measurements. Since migraine is a condition that can profoundly affect functional ability and quality of life, self-reports of the severity and impact of attacks are crucial to understand the effectiveness of treatment [26]. However, the current study demonstrated low utilization of PRO instruments in clinical practice, with only 6% and 15% of patient charts reporting MIDAS and HIT-6™ scores, respectively, in both the baseline and study periods. The severity when assessed by MIDAS and HIT-6™ in the study period remained at the severe disability level. However, the small proportion of patients with PRO measurements in this study may not be representative of the broader migraine population in the real world and may be biased towards more severe patients who may be more likely to complete the questionnaire. Notably, among patients for whom severity was assessed by physicians instead of or in addition to the PRO instruments, patients had a reduction in migraine severity as assessed by physicians from baseline to study period. On the basis of this limited use of PRO measurements, there is a need for the identification and systematic application of specific PROs that may be useful to patients and physicians in the management of migraine. A systematic review of headache/migraine PRO measures found that most lack clarity with regards to measurement validity, which limits their interpretation and utility in both clinical research and routine practice settings [26]. Newer PRO measures that incorporate valuable patient input in the development process and rely on shorter recall periods, like the Migraine Functional Impact Questionnaire (MFIQ), may help to address this unmet need [27].

In addition to an improvement in patient outcomes, the current study also demonstrated a reduction in the number of monthly outpatient visits after erenumab initiation. Of note, initial visits following the initiation of erenumab may have been related to routine follow-up and monitoring of the newly initiated treatment; therefore, further reductions in HRU may occur as patients remain on treatment with erenumab.

Limitations

The findings of this study should be interpreted in light of some limitations. As with all chart review studies, there is the potential for missing or inaccurate data recorded in the patient charts and lack of standardization in physician reporting of data in charts across centers. Physicians may only have had access to data related to care provided at their center. Additionally, headache and migraine days were not assessed separately, and only abstracted from information available in patient charts, which may lack granularity or consistency across centers. Moreover, PRO measurements were only available for a small subset of the sample. Results may not be generalizable to all patients with migraine and to those with episodic migraine or patients treated in other settings, given this study focused on patients with chronic migraine from select participating headache centers who were required to have been treated with erenumab for at least 3 months. Additionally, treatment exposure to erenumab was variable, with patients treated for an average of 9 months. To minimize the recency bias of physicians selecting charts from patients seen recently, centers were advised to select patient charts on the basis of a method of random selection (e.g., reverse alphabetical order). In addition, centers were selected on the basis of having a significant number of patients with migraine treated with erenumab and may not be representative of general US treatment practices for patients with migraine. Lastly, given that erenumab had been available for less than 2 years at the time of chart abstraction, the results reported in this study describe erenumab use for centers that can be considered as “early adopters” of anti-CGRP pathway-targeting therapies. One reason for early adoption of erenumab may be because patients had failed multiple preventive treatments. Future studies should assess erenumab use among patients treated with erenumab in earlier treatment lines.

Conclusions

The real-world evidence presented in this study supports previous clinical findings of the benefit of erenumab in the management of chronic migraine, including a reduction in the monthly frequency of headache/migraine in a predominantly treatment-refractory population (multiple preventive treatment failures). Despite the demonstrated effectiveness of erenumab, patients treated in the five US headache centers largely continued to be managed via a polypharmacy approach in the initial months after erenumab initiation. Further long-term research across various clinical practice settings is needed to better understand real-world patient outcomes and treatment patterns with erenumab therapy.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Financial support for this research was provided by Amgen Inc (Thousand Oaks, CA), including the funding of the journal’s Rapid Service Fee. The study sponsor was involved in several aspects of the research, including the study design, the interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Medical Writing Assistance

Medical writing support was provided by Christine Tam (Analysis Group, Inc). Funding was not provided specifically for this medical writing support.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authors’ Contributions

EF, IP, KY, KAB, EQW, and DC contributed to study conception and design, collection and assembly of data, and data analysis and interpretation. MB, DEC, and DC contributed to study conception and design, and data analysis and interpretation. ZA, SJ, RH, AB, JS, AF, and KC contributed to collection of data and interpretation. All authors reviewed and approved the final content of this manuscript.

Prior Presentation

Part of the material in this manuscript was presented at the Migraine Trust Virtual Symposium from October 3–9, 2020 and at the American Headache Society Annual Scientific Meeting from July 11–14, 2019 in Philadelphia, PA.

Disclosures:

Elizabeth Faust, Irina Pivneva, Karen Yang, Keith A. Betts, and Eric Q. Wu are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Amgen Inc., which funded the development and conduct of this study and manuscript. Mark Bensink, Denise E. Chou, and David Chandler are employees of Amgen Inc. Zubair Ahmed and Andrew Blumenfeld have provided consulting services to and served on the Advisory Board of Amgen Inc. No conflict for Shivang Joshi, Rebecca Hogan, Jack Schim, Alexander Feoktistov, and Kenneth Carnes.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All data were extracted from existing medical records and de-identified. Ethics review was conducted by individual centers with an internal review process. For Cleveland Clinic participation, expedited ethics review was approved by Cleveland Clinic IRB (IRB 19-614), which has an internal review process. New England Institutional Review Board exemption (IRB# 120190088) was received for the remaining centers.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to data collected via an eCRF from key headache centers with IRB approval.

References

- 1.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1):1–211. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, et al. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;68(5):343–349. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252808.97649.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Global Burden of Disease Study Collaborators Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1211–1259. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawkins K, Wang S, Rupnow M. Direct cost burden among insured US employees with migraine. Headache. 2008;48(4):553–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawkins K, Wang S, Rupnow MF. Indirect cost burden of migraine in the United States. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49(4):368–374. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31803b9510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hazard E, Munakata J, Bigal ME, Rupnow MF, Lipton RB. The burden of migraine in the United States: current and emerging perspectives on disease management and economic analysis. Value Health. 2009;12(1):55–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu XH, Markson LE, Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Berger ML. Burden of migraine in the United States: disability and economic costs. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(8):813–818. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.8.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Headache Society The American Headache Society position statement on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache. 2018;59(1):1–18. doi: 10.1111/head.13456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Food and Drug Administration (FDA). FDA approves novel preventive treatment for migraine 2018. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-novel-preventive-treatment-migraine#:~:text=The%20U.S.%20Food%20and%20Drug,once%2Dmonthly%20self%2Dinjections. Accessed 19 Oct 2020.

- 10.Eli Lilly and Company. Highlights of prescribing information—EMGALITY (galcanezumab). 2019. p. 1–38.

- 11.Lundbeck Seattle BioPharmaceuticals, Inc. Highlights of prescribing information—VYEPTI (eptinezumab-jjmr). 2020. p. 1–13.

- 12.Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. Highlights of prescribing information—AJOVY (fremanezumab-vfrm). 2020. p. 1–9.

- 13.Dodick DW, Ashina M, Brandes JL, et al. ARISE: a phase 3 randomized trial of erenumab for episodic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(6):1026–1037. doi: 10.1177/0333102418759786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reuter U, Goadsby PJ, Lanteri-Minet M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of erenumab in patients with episodic migraine in whom two-to-four previous preventive treatments were unsuccessful: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b study. Lancet. 2018;392(10161):2280–2287. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32534-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tepper S, Ashina M, Reuter U, et al. Safety and efficacy of erenumab for preventive treatment of chronic migraine: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(6):425–434. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanaan S, Hettie G, Loder E, Burch R. Real-world effectiveness and tolerability of erenumab: a retrospective cohort study. Cephalalgia. 2020;40(13):1511–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Lambru G, Hill B, Murphy M, Tylova I, Andreou AP. A prospective real-world analysis of erenumab in refractory chronic migraine. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):61. doi: 10.1186/s10194-020-01127-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robblee J, Devick KL, Mendez N, Potter J, Slonaker J, Starling AJ. Real-world patient experience with erenumab for the preventive treatment of migraine. Headache. 2020;60(9):2014–2025. doi: 10.1111/head.13951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ornello R, Casalena A, Frattale I, et al. Real-life data on the efficacy and safety of erenumab in the Abruzzo region, central Italy. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s10194-020-01102-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.di Cola SF, Rao R, Caratozzolo S, et al. Erenumab efficacy in chronic migraine and medication overuse: a real-life multicentric Italian observational study. Neurol Sci. 2020;41(Suppl 2):489–490. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04670-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amgen Inc. Highlights of prescribing information—AIMOVIG (erenumab-aooe). 2020. p. 1–44.

- 22.Goadsby PJ, Reuter U, Hallström Y, et al. A controlled trial of erenumab for episodic migraine. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(22):2123–2132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1705848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buse DC, Manack A, Serrano D, Turkel C, Lipton RB. Sociodemographic and comorbidity profiles of chronic migraine and episodic migraine sufferers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81(4):428–432. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.192492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deen M, Correnti E, Kamm K, et al. Blocking CGRP in migraine patients—a review of pros and cons. J Headache Pain. 2017;18(1):96. doi: 10.1186/s10194-017-0807-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalso E, Edwards JE, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Opioids in chronic non-cancer pain: systematic review of efficacy and safety. Pain. 2004;112(3):372–380. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haywood KL, Mars TS, Potter R, Patel S, Matharu M, Underwood M. Assessing the impact of headaches and the outcomes of treatment: a systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) Cephalalgia. 2018;38(7):1374–1386. doi: 10.1177/0333102417731348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawata AK, Hareendran A, Shaffer S, et al. Evaluating the psychometric properties of the migraine functional impact questionnaire (MFIQ) Headache. 2019;59(8):1253–1269. doi: 10.1111/head.13569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to data collected via an eCRF from key headache centers with IRB approval.