Abstract

Limnocharis flava (L.) Buchenau is a problematic weed in rice fields and water canals of Southeast Asia, and in Malaysia this invasive aquatic weed species has evolved multiple resistance to synthetic auxin herbicide and acetohydroxyacid synthase (AHAS) inhibitors. In this study, it was revealed that, a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) at amino acid position 376, where C was substituted to G at the third base of the same codon (GAC to GAG), resulting in Aspartate (Asp) substitution by Glutamate (Glu) was the contributing resistance mechanism in the L. flava population to AHAS inhibitors. In vitro assay further proved that, all the L. flava individuals carrying AHAS resistance mutation exhibited decreased-sensitivity to AHAS inhibitors at the enzyme level. In the bensulfuron-methyl whole-plant bioassay, high resistance indices (RI) of 328- and 437-fold were recorded in the absence and presence of malathion (the P450 inhibitor), respectively. Similarly, translocation and absorption of bensulfuron-methyl in both resistant and susceptible L. flava populations showed no remarkable differences, hence eliminated the possible co-existence of non-target-site resistance mechanism in the resistant L. flava. This study has confirmed another new case of a target-site resistant weed species to AHAS-inhibitors.

Keywords: Acetohydroxyacid synthase, Amino acid substitution, Target site resistance, Herbicide resistance, Limnocharis flava

Introduction

Rice cultivation in Peninsular Malaysia is mainly irrigated, practiced double-season throughout the year, and approximately 70% of the rice growers across all rice granaries are practicing direct seeding methods. In direct-seeded rice fields, weeds have been recognized as the single major biological constraint (Mathloob et al. 2015) making their control utmost crucial to reduce the risk of yield loss. To overcome this problem, herbicides have become the preferred choice by many Malaysian rice growers (Ruzmi et al. 2017). The acetohydroxyacid synthase (AHAS) inhibitors are frequently and widely used herbicides for early post-emergence weeds control in rice fields because of its high efficiency and selectivity towards rice crop. Nevertheless, intensive selection pressure by AHAS inhibitors for weed control has taken its toll, resultantly causing many weed populations to develop resistance to AHAS inhibitors. Hitherto, predominant rice field weeds worldwide such as Echinochloa phyllopogon (Stapf) Koss., Monochoria korsakowii Regel & Maack, Cyperus difformis L., Schoenoplectus mucronatus (L.) Palla, Monochoria vaginalis (Burm.f.) C. Presl ex Kunth, Sagittaria trifolia L., Alisma plantago-aquatica L., and Cyperus iria L. have been listed as problematic, AHAS-inhibitors resistant weeds in rice fields (Osuna et al. 2002; Kuk et al. 2003a, b; Busi et al. 2006; Calha et al. 2007; Merotto et al. 2009; Iwakami et al. 2014; Riar et al. 2015; Wei et al. 2015; Ruzmi et al. 2017). Currently in Malaysian rice fields, eight rice weed species have been known resistant to various herbicide modes of action and one of the resistant weed species is Limnocharis flava. This weed was first identified as a multiple herbicide-resistant weed species including AHAS inhibitor bensulfuron-methyl as early as 1998 (Heap 2021) and is still largely infesting many rice fields in Malaysia (Karim et al. 2004).

The plant-chloroplast AHAS (EC 2.2.1.6) is a catalytic enzyme responsible in the de novo biosynthesis of branched-chain amino acids isoleucine, leucine, and valine. The binding by AHAS inhibitors arrests the AHAS function and activity, further halts the biosynthesis of these amino acids, finally leading to the failure of protein synthesis and cause plant death (Tranel and Wright 2002; Yu and Powles 2014). AHAS inhibitors comprised of five groups, namely imidazolinones (IMI), pyrimidinyl(thio)benzoates (PTB), sulfonylaminocarbonyl-triazolinones (SCT), sulfonylureas (SU), and triazolopyrimidine sulfonanilides (TP). Commonly, the classification of cross-resistance patterns related to AHAS substitutions are IMI and PTB resistant, SU and TP resistant, or broad cross-resistance, if the species is resistant to all four classes of inhibitors (Tranel and Wright 2002). Two resistance mechanisms have been proposed on resistance evolution to AHAS inhibitors in weeds, particularly target-site resistance (TSR) and non-target-site resistance (NTSR). By all means, modifications of the herbicide binding site and increased metabolism of herbicides catalyzed by cytochrome P450 monooxygenases have been commonly associated with resistance to AHAS inhibitors (Powles and Yu 2010; Riar et al. 2015). In many reported cases, target-site resistance, conferred by the amino acid substitutions, which result in the insensitivity of target enzyme to the herbicides have been extensively investigated. Twenty-seven resistance substitutions have been reported at eight sites across AHAS gene: Alanine122 (n = 3), Proline197 (n = 12), Alanine205 (n = 2), Aspartate376 (n = 1), Arginine377 (n = 1), Tryptophan574 (n = 3), Serine653 (n = 3), and Glycine654 (n = 2), where n refers the number of different substitutions of amino acid reported worldwide (Yu and Powles 2014; Tranel et al. 2017; Brosnan et al. 2016). Additionally, the co-existence of TSR and NTSR toward AHAS inhibitors is also evident in the resistant weed populations (Yang et al. 2016).

Limnocharis flava, locally known as Paku rawan, is an emergent aquatic plant causing a threat to the environmental integrity of wetlands. Belonging to the Limnocharitaceae/Alismataceae family, L. flava invades the irrigation systems and compete with inhabitant plants for growth resources, impeding the native aquatic flora, ultimately resulting in the ecological imbalance (Juraimi et al. 2012; Weber and Brooks 2013). In humid regions, this self-pollinated herbaceous aquatic weed species originally behaves as perennial species, but capable to shorten its life cycle as an annual plant in definite dry seasons. L. flava is a diploid, autogamy, monocotyledonous species propagates mainly by seeds, and also vegetative by producing new shoots via its peduncles (Weber and Brooks 2013). Limnocharis flava becomes pest of rice fields and serious invasive aquatic environmental weed from India to all over Southeast Asia, Australia and America. Infestation in rice fields and water bodies began when seeds from this weed escaped into nature, grew and mixed up with the rice, and became seed contaminant in rice, as reported in India (Weber and Brooks 2013).

Limnocharis flava infests rice fields by occupying empty spaces (e.g. between rows). Once it establishes, it will rapidly occupy the infested area, outcompetes rice plants. In a worst-case scenario, farmers had to abandon rice fields when high infestation (> 50% coverage) occurred (CABI 2013). According to Waterhouse and Mitchell (1998), Indonesia, Malaysia and Sri Lanka are countries facing serious infestation of L. flava in rice fields. In Malaysia, L. flava predominantly infests rice fields in the majority of rice granaries, because of its capability to thrive in a wide range of water regimes (field capacity, saturated, and different flooding conditions) (Karim et al. 2004; Hakim et al. 2013; Juraimi et al. 2012), making this weed as among the top concerned weed species in Malaysian rice fields. This marginal-type aquatic weed species has been also reported to evolve resistance to bensulfuron-methyl and 2,4-D (synthetic auxin herbicide) (Juraimi et al. 2012), later confirmed to exhibit cross-resistance to several AHAS inhibitors (Zakaria et al. 2018) in Malaysia. L. flava was also observed to develop resistance to synthetic auxin herbicides in Indonesia, although no further details were provided (Heap 2021). Nonetheless, the elucidation on resistance mechanisms in the herbicide-resistant L. flava has not been clarified. This study identified the possible AHAS-inhibitors target-site AHAS gene mutation and non-target-site metabolic resistance mechanisms in a resistant L. flava population, which could help researchers analyze resistance risk to other herbicide modes of action, further developing potential integrated management strategies for a more sustainable control of this aquatic weed species.

Materials and methods

Plant material

The AHAS-inhibitor resistant Limnocharis flava (hereinafter called as R) plants used in this study originated from the field-evolved resistant population in Malaysian Agriculture Research and Development Institute (MARDI) commercial rice fields, Bertam, Seberang Perai, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia (5°32′37"N, 100°28′3"E). In a recent AHAS-inhibitors whole-plant dose–response study, it was revealed that this R L. flava population has developed cross-resistance to AHAS inhibitors at different levels, particularly highly resistant to bensulfuron-methyl, moderate resistance to metsulfuron-methyl, and low resistance to pyrazosulfuron-ethyl and pyribenzoxim (Zakaria et al. 2018). The AHAS-inhibitor susceptible (hereinafter called as S) L. flava population seeds were collected from surrounding non-field areas with no known herbicide exposure. Leaf material of individual R plants that survived all AHAS inhibitors at recommended rate and above in the dose–response study (Zakaria et al. 2018), plus unsprayed S plants were taken, and used to elucidate the plausible mechanism(s) conferring resistance to AHAS inhibitors, as described below. All collected plant materials were cleaned and kept at −20 °C in the Weed Science Laboratory, Faculty of Agriculture, Universiti Putra Malaysia. The AHAS-inhibitors whole-plant bioassays were conducted in the faculty glasshouse compound, with a day/night temperature of 33/20 °C and average daylight intensity of 250–350 µmol m−2 s−1 (Extech® light meter model 407026).

De novo RNA sequencing

A total of 5 g of fresh leaf tissue was harvested from untreated S plants and stored at −80 °C prior for molecular analysis. For RNA isolation, the frozen leaf tissue sample was ground in liquid nitrogen prior to RNA extraction. To validate the extracted RNA quality, 1 µL of the final product was run on 1% agarose gel to monitor the RNA contamination and degradation. RNA purity was quantified by NanoPhotometer® spectrophotometer (IMPLEN, CA, USA). Determination of the extracted RNA concentration was done using the Qubit® RNA Assay Kit in Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, CA, USA). The RNA integrity was quantified using RNA 6000 Nano Assay Kit with the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA).

Sequencing libraries were prepared by using NEBNext® Ultra™ RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (NEB, USA), as accordance to the manufacturer’s recommendation. In brief, mRNA was purified by using poly-T oligo-attached magnetic beads. Under elevated temperature, fragmentation was accomplished by using divalent cations in NEBNext® First Strand Synthesis Reaction Buffer (5X). The first cDNA strand was synthesised by using random hexamer primer and M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase (RNase H), whereas the second cDNA strand was synthesized using DNA-Polymerase I and RNase H. NEBNext Adaptor incorporated with hairpin loop structure were ligated for hybridisation after the adenylation of 3′ ends of DNA fragments. Purification of the library fragments was done using the AMPure® XP system (Beckman Coulter, Beverly, USA), in order to pick out cDNA fragments with 150 ~ 200 base pair (bp) in length. Later, 3 µl of USER Enzyme (NEB, USA) was used with the adaptor-ligated and size-selected cDNA for 15 min at 37 °C, followed by 5 min at 95 °C. PCR was performed with Phusion® High-Fidelity DNA polymerase, universal PCR primer and Index [X] Primer. After that, PCR products were purified (AMPure® XP system) and the library quality was examined on the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer system.

The index-coded samples were clustered on a cBot Cluster Generation System by using TruSeq PE Cluster Kit v3-cBot-HS (Illumia). After the clusters were successfully generated, the library preparations were sequenced using an Illumina Hiseq platform. Raw data in form of fastq format were run through in-house Perl scripts. Transcriptome assembly was prepared by using Trinity Picard-tools v1.41 (Grabherr et al. 2011). From the de novo assembly, acetohydroxyacid synthase (AHAS) gene fragments of L. flava were identified by using BLAST. The sequence reads were assembled and aligned comparable to the acetolactate synthase of Sagittaria pygmaea Miq. (GenBank Accession No: BAH60833.1).

Genomic DNA extraction and AHAS gene sequencing

In total, eighty-four leaf samples from R plants and five leaf samples from S plants were taken (approximately 2 g per plant), snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for genomic DNA extraction and AHAS gene sequencing study. The frozen material was ground by using pestle and mortar in liquid nitrogen to a fine powder. One hundred milligrams of leaf powder were then immediately suspended in 400 µL SLS- buffer of “innuPREP Plant DNA kit” (Analytikjena, Germany). Genomic DNA was extracted following the manufacturer's protocols. Quantification of the purity (absorbance ratio 260/230 and 260/280) and concentration (absorbance at 260 nm) of the extracted DNA was done using NanoDrop Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, USA). The genomic DNA integrity was examined by resolving DNA extracts on a 1% agarose gel electrophoresis (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

To identify the molecular basis of resistance to AHAS inhibitors in the R L. flava, the AHAS gene fragment, 2178 base pairs (bp) in length, which comprised all six conserved regions, namely domains A, B, C, D, E, and F (Merotto et al. 2009) in both R and S populations were amplified, sequenced, and compared. Primer pair to amplify and sequence L. flava AHAS gene fragment were specifically designed from alignment of L. flava AHAS gene sequence (GenBank Accession No: KX891189). The primer pair, 5′-ACCGCCCGTGCTTATCTTTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCAGTATGAAGTTCTGCCATCTCC-3′ (reverse) were specifically designed using Primer Premier software (v.6.1) (Premier Biosoft Interpairs, Palo Alto, CA). A primer pair amplified the AHAS gene comprising all eight-known resistance endowing amino acids substitution accounting for 100% of the conserved plant AHAS sequence.

A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was run in a total volume of 15 µl that contained of 7.5 µl of PCR Mastermix (Bioline, GmbH, Germany), 1.0 µl of DNA (70 ng µl−1), 1 µl of each primer (10 mM). The PCR was run in a Thermal Cycler T100 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using the following cycles: 94 °C for 5 min, then 35 cycles of 45 s at 94 °C, 45 s at 62 °C and 1 min at 72 °C, followed by final elongation step subjected to 10 min at 72 °C. One percent agarose gels stained with FluroSafe DNA stain (Axil Scientific Pte Ltd, Singapore) were used to analyse PCR products and a 1 kb DNA ladder (Fermentas, Thermo Scientific) as a reference. The PCR products were purified from agarose gel using Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-up System (Promega), and a commercial sequencing service (First BASE Laboratories Sdn. Bhd.) was used to sequence the purified PCR products. DNA Sequence Assembler v4 (Heracle BioSoft, www.DnaBaser.com) was used to align and compare the DNA and deduced amino acid sequence between R and S populations.

AHAS in vitro activity and inhibition

The R individuals that survived the highest herbicide dose from the AHAS-inhibitors dose–response experiment (Zakaria et al. 2018) were maintained in the glasshouse until maturity to produce seeds for in vitro AHAS activity assays. Preparation of seeds for germination and plant growth in the glasshouse prior to shoot sampling referred to the procedures for whole-plant dose–response as described in Zakaria et al. (2018). In brief, a total of eight 1–2-leaf stage seedlings from populations R and S were transplanted at a depth of 1 cm in 15 cm-diameter pots. The plants were maintained in a glasshouse under shallow flooded conditions (2–3 cm water depth) throughout the experimental period. Fertilizers were applied at 170 kg ha−1 N, 80 kg ha−1 P2O5, and 150 kg ha−1 K2O every fortnight.

Approximately 4 g of leaf tissue (about 6–7 plants) from 4–5-leaf stage seedlings of R individuals known to harbor resistance mutation and untreated S plants were harvested, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept at −80 °C. The AHAS in vitro assay was carried out in accordance with Yu et al. (2010) with minor alterations. Certified analytical standard for AHAS inhibitors bensulfuron-methyl (99.6%), metsulfuron-methyl (99.2%), pyrazosulfuron-ethyl (99.1%), and pyribenzoxim (99.8%) were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (Sigma-Aldrich Laborchemikalien GmbH, Germany).

All AHAS inhibitors were dissolved in 20% acetone prior to reaction mixture. Protein concentration of the extract was quantified using the Bradford method (Bradford 1976). Acetoin formed from acetolactate was quantified colorimetrically at 530 nm. Concentrations of AHAS inhibitors used (µM) were 0, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100, and 1000 for both populations. Three independent experiments, each with a respective enzyme assay from different plant materials were performed for each population, and each herbicide concentration was assayed four times per sample.

Whole-plant metabolic resistance mechanism to bensulfuron-methyl in Limnocharis flava

The seeds of AHAS inhibitor-resistant (R) L. flava population that survived bensulfuron-methyl, metsulfuron-methyl, pyrazosulfuron-ethyl, and pyribenzoxim at the recommended rate, and untreated susceptible (S) were used. The AHAS-resistant mutation Asp-376-Glu is present in R individuals and its presence was confirmed by DNA sequencing in all R plants, which meets the minimum requirement of at least three individuals, as demonstrated by Tardif et al. (2006). Seed germination protocol and planting condition for L. flava was in accordance to the previous study (Zakaria et al. 2018).

The existence of NTSR mediated by P450-induced rapid metabolism of AHAS inhibitors in the R L. flava population was studied using insecticide malathion (Mapa Malathion 57, 57% w/w ai, Hextar Chemicals Sdn. Bhd., Selangor, Malaysia) as an indicator. Each pot contained 10 seedlings, and plants at 4–5-leaf stage of R and S populations were treated with bensulfuron-methyl (Buron 600, 60% w/w ai, Farmcochem Sdn. Bhd., Perak, Malaysia) at seven dosages, namely 0, 10, 20, 40 (recommended rate), 80, 160, 320 g ai ha−1, either alone or following malathion application. Malathion was mixed with tap water and applied at the recommended rate (2.25 L ha−1) 60 min prior to the application of bensulfuron-methyl. Bensulfuron-methyl was diluted in tap water and adjuvant (MPC Padix, Agrow Synergy (M) Sdn. Bhd., Selangor, Malaysia) was added at 0.15% v/v. A rechargeable battery-knapsack type sprayer with adjustable flat fan nozzle, delivering 200 L ha−1 at spray pressure of 150 kPa (Masato, Japan) was used. Assessment on plant survival was accomplished 21 days after treatment and plants were harvested 1 cm aboveground, oven-dried at 65° for 72 h, and weighed. Experiment was replicated thrice.

Bensulfuron-methyl absorption and translocation in resistant L. flava

Ten seedlings of 4–5-leaf stage R and S plants selected for the bensulfuron-methyl absorption and translocation were treated according to the specifications of previous studies with minor modifications (Zhang et al. 2013; Li et al. 2016). Bensulfuron-methyl was prepared at the recommended rate (40 g ai ha−1) and ten 2 μL droplets of the prepared herbicide solution were carefully applied onto the 3rd leaf, located midway up the stem, using a volumetric pipette. Plants were maintained in the glasshouse until harvest. Both treated R and S plants were harvested into six parts: (i) the treated leaf (TL); (ii) the leaf above the treated leaf (LATL); (iii) the leaf below the treated leaf (LBTL); (iv) the stem of treated leaf (STL); (v) the stem of leaf above the treated leaf (SLATL), and (vi) the stem of leaf below the treated leaf (SLBTL) at 24, 48, and 72 h after treatment (HAT), and stored at −20 °C. The treated leaves were washed with deionised water, then chloroform was added to remove any remaining herbicide residue on the surface. Each plant part was individually sampled to obtain a minimum weight of 6 g per treatment (2 g per replication for each treatment). The TL was used to quantify bensulfuron-methyl absorption, while bensulfuron-methyl translocation was determined in other plant parts.

All harvested plant parts were ground separately in liquid nitrogen using sterilized pestle and mortar, immediately transferred into a 50 mL polytetrafluoroethylene centrifuge tube. A total of 10 mL of acetonitrile was slowly added, then the samples were shaken on an orbital shaker (Hotech 702 R, Taipei, Taiwan) at 200 rpm for 30 min. Three (3) g of sodium chloride was added, followed by vortex for 1 min and the extract was centrifuged at 4000 r/min (Eppendorf 5810 R, Hamburg, Germany) for 5 min. 1 mL of the upper layer was taken out by using a syringe pump (Terumo, Japan) and filtered through 0.2 μm nylon syringe filters (Whatman). The extracted solutions were injected into the High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Authentication of the extraction method was verified through calculation of the average recoveries. The peak area data of bensulfuron-methyl at different HATs in both R and S populations were compared.

Recovery studies

The untreated L. flava leaves (2 g per replicates) were delicately ground in liquid nitrogen. Samples for recovery studies were spiked with bensulfuron-methyl at concentrations of 0.005, 0.01, and 0.02 mg/ml and left for 30 min prior to extraction. Authentication of the extraction method was verified as accordance to a standard protocol by the Malaysian Nuclear Agency. The extraction method for recovery studies was similar to bensulfuron-methyl absorption and translocation experiment as detailed above. The samples were extracted and three replicates were prepared at each concentration and each replicate was injected in triplicate. High recoveries were obtained in all concentrations (> 83%), with the lowest recovery was obtained from the highest spiked concentration (Table 1).

Table 1.

Average Recoveries (%) and Relative Standard Deviation (RSD, %) at bensulfuron-methyl concentration of 0.005, 0.01 and 0.02 mg/mL

| Average recoveries % (RSD, %) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.005 mg/mL | 0.01 mg/mL | 0.02 mg/mL | |

| Bensulfuron-methyl | 88.96 (4.2) | 103.57 (4.3) | 83.5 (5.6) |

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis

The HPLC analysis was conducted on a Shimadzu HPLC system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) using C18 reversed phase column (Luna® 5 µm C18 (2) 100 Å, LC Column 250 × 4.6 mm i.d Phenomenex). This HPLC system is equipped with SPD-20A detector, a LC-20AD pump, a SIL-20A auto sampler, and a DGU-20-A5 degasser. The detector was set between 190 to 300 nm. The column oven was set to 30 °C. The solvent flow rate was 1 mL min−1 during the whole process and a total of 40 µl of sample was injected in each run.

The HPLC analytical conditions were slightly modified from the certified analytical standard of bensulfuron-methyl (99.6%) (Sigma-Aldrich Laborchemikalien, GmbH, Germany) to optimize the separation process. The mobile phases, A and B, were aqueous 0.1% formic acid and acetonitrile. The initial mobile phase composition was A/B = 60:40, held constant from 0.00 to 5.00 min. A gradient was then programmed to increase the volume of B from 40 to 80% in 10.00 min and later kept constant at 80% for 15.00 min. Solvents were filtered through a 0.2 µm × 47 mm nylon filter membrane (Phenex) and all solvents and deionized water were degassed prior to injection.

The analytical standard calibration of bensulfuron-methyl (99.6%) was dissolved in a mixture of acetonitrile: aqueous 0.1% formic acid (40:60, v/v). The concentration of stock standard solution was 0.2 mg mL−1. The calibration curve was prepared by diluting the stock solution at six concentrations, namely 0.001, 0.005, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, and 0.2 mg mL−1. The solutions were filtered through a 0.2 µm × 13 mm nylon syringe filters (Whatman). The concentration of bensulfuron-methyl in the samples were quantified from peak areas of the samples and the corresponding standard using calibration curve.

Statistical analysis

All pots in the increased metabolism, reduced absorption, and translocation of bensulfuron-methyl experiments were arranged in a randomized complete block design (RCBD), with three replicates. All data from the herbicide dose–response studies were expressed as the percentage of untreated controls and subjected to regression analysis using SigmaPlot 11.0 (Systat Software Inc., GmbH, Germany). The I50 (herbicide concentration causing 50% inhibition of in vitro AHAS activity), LD50 (herbicide dose causing 50% reduction in plant survival), and GR50 (herbicide dose causing 50% reduction in dry weight of plant) were calculated using two regression models, whichever fit best, either the four-parameter log-logistic model (Seefeldt et al. 1995):

where c is the lower limit, d is the upper limit, b is the slope and (ED50) is a dose causing 50% reduction, or the three-parameter exponential decay model:

where y0 is the lower limit, yo + a is the upper limit, b is the slope of the curve and x is the dose causing 50% response. The resistance index (RI) for I50, LD50, and GR50 were calculated to indicate the level of resistance in the R population over the S population.

Both datasets (plant survival rate and dry weight) were expressed as percentage of control. To determine any significant difference among treatments, a two-way ANOVA was performed using SAS software (SAS, Version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., North Carolina, USA). Separation of the means at 0.05 probability level was conducted using the LSD test, as outlined in SAS procedure.

Results

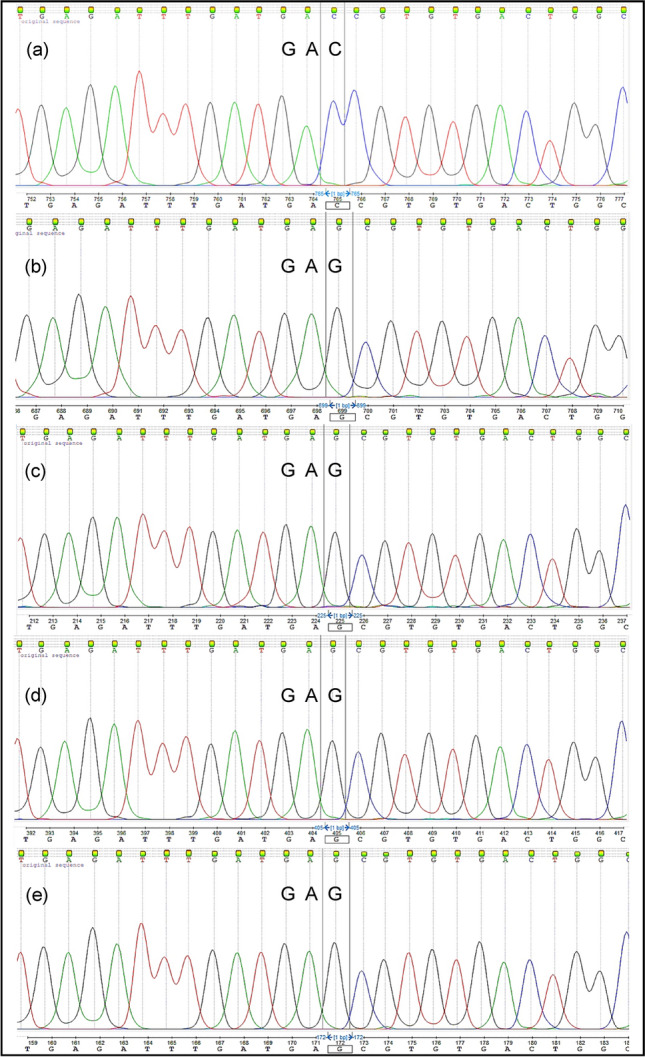

AHAS gene sequencing revealed an Asp-376-Glu substitution in the R L. flava population

The AHAS gene of S L. flava was sequenced for the first time and the nucleotide sequence was registered to GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank) with an Accession No. KX891189. Malaysia is the first country to report the occurrence of resistance to AHAS inhibitors in L. flava, thus the de novo sequencing and assembling of the target AHAS gene were accomplished because there was no reference sequence available for L. flava. The sequence with 2178 bp size was amplified using the designed primer covering eight known resistance-endowing amino acids of the conserved plant AHAS sequence. Based on the BLAST search in NCBI database using this amplified AHAS gene sequence of S L. flava, it was confirmed that the L. flava AHAS gene region has 84% amino acid similarity with another weed species from the family Alismataceae Sagittaria pygmea (GenBank Accession No. AB477097.1).

The chromatogram of the AHAS sequencing results revealed that the Asp-376-Glu mutation in R plants was homozygous (single peak). All individuals in the R population were confirmed carrying a single mutation, which disrupted Aspartate (Asp-GAC/GAT) codon in Domain F, a conserved region at position 376 in the AHAS gene. A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) was observed at position 376 resulted in single base pair substitution by Glutamate (Glu-GAG) in the AHAS coding region in R plants. Sequence comparison of all eighty-four individual R plants that survived AHAS inhibitors bensulfuron-methyl, metsulfuron-methyl, pyrazosulfuron-ethyl, and pyribenzoxim in the dose–response study (Zakaria et al. 2018) revealed that all individuals carry similar mutation at position 376 (Fig. 1). Evidently, there was no difference in nucleotide sequences of AHAS gene between R and S populations at positions 122, 197, 205, 377, 574, 653, and 654, which have been reported carrying resistance-endowing mutations in numerous weed species (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

DNA sequencing results. a The GAC codon for Asp-376 in homozygous susceptible plants, b–e The GAG codon for Asp-376- Glu in homozygous resistant plant treated with herbicide bensulfuron-methyl, metsulfuron- methyl, pyrazosulfuron- ethyl and pyribenzoxim, respectively. Note: Line color represent: Black:Guanine; Red:Thymine; Green:Adenine: Blue:Cytosin

Table 2.

Codons of acetohydroxcyacid synthase and derived amino acid at eight sites in AHAS-inhibitor susceptible Arabidopsis thaliana (NM_114714), and AHAS-inhibitor susceptible (S) and resistant (R) Limnocharis flava

| Accession | Ala122 | Pro197 | Ala205 | Asp376 | Arg377 | Trp574 | Ser653 | Gly654 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Codon | Amino acid | Codon | Amino acid | Codon | Amino acid | Codon | Amino acid | Codon | Amino acid | Codon | Amino acid | Codon | Amino acid | Codon | Amino acid | |

| Arabidopsis thaliana (S) | GCA | Ala | CCT | Pro | GCG | Ala | GAT | Asp | CGT | Arg | TGG | Trp | AGT | Ser | GGT | Gly |

| Limnocharis flava (S) | GCT | Ala | CCC | Pro | GCC | Ala | GAC | Asp | CGT | Arg | TGG | Trp | AGT | Ser | GGA | Gly |

| Limnocharis flava (R) | GCT | Ala | CCC | Pro | GCC | Ala | GAG | Glu | CGT | Arg | TGG | Trp | AGT | Ser | GGA | Gly |

The bold nucleotide bases encode Asp376 in the S population and amino acid mutation in the R population. The nucleotides and resultant amino acids are in abbreviation: Ala, Alanine; Pro, Proline; Asp, Aspartate; Glu, Glutamate; Arg, Arginine; Trp, Tryptophan; Ser, Serine; Asn, Asparagine; Gly, Glycine

AHAS in vitro activity and inhibition further support the existence of TSR in the R L. flava

Different AHAS inhibitors categorized in the family of PTB (pyribenzoxim) and SU (bensulfuron-methyl, pyrazosulfuron-ethyl, metsulfuron-methyl) were used for determination of 50% enzyme inhibition (I50). In vitro AHAS assay has shown that the total AHAS activity extracted in the absence of herbicides for S and R populations were statistically different (1.528b and 2.378a nmol acetoin formed mg−1 protein min−1, respectively). The extracted AHAS enzyme from R population was insensitive to all AHAS inhibitors, in contrast to the sensitive AHAS enzyme in S population (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5). The R AHAS enzyme was 48-fold resistant to PTB (pyribenzoxim), in which the lowest level of resistance among the tested AHAS inhibitors (Table 3). Resistance to SU class at the enzyme level for bensulfuron-methyl was the highest at > 83,333-fold, while it was 398-fold in metsulfuron-methyl and 172-fold for pyrazosulfuron-ethyl (Table 3). Evidently, the Asp-376-Glu mutation endowed a high resistance level to bensulfuron-methyl, metsulfuron-methyl, and pyrazosulfuron-ethyl, and lower to pyribenzoxim in the R L. flava, similar to the results obtained in the whole-plant dose–response (Zakaria et al. 2018). Apparently, the I50 RI was also much higher than RI of LD50 (Zakaria et al. 2018), strongly establishing that an altered AHAS enzyme as the basis of resistance mechanism in the R L. flava. Similarly, previous studies have indicated higher RI values in I50 in comparison to RI values in LD50 in other weed species (Ashigh et al. 2009; Sada et al. 2013).

Fig. 2.

In vitro inhibition of AHAS activity in presence of bensulfuron- methyl. Susceptible (S) and resistant (R) Limnocharis flava populations. Data were averaged from three extractions per population and each was assayed four times with standard error of the mean

Fig. 3.

In vitro inhibition of AHAS activity by metsulfuron- methyl. Susceptible (S) and resistant (R) Limnocharis flava populations. Data were averaged from three extractions per population and each was assayed four times with standard error of the mean

Fig. 4.

In vitro inhibition of AHAS activity by pyrazosulfuron- ethyl. Susceptible (S) and resistant (R) Limnocharis flava populations. Data were averaged from three extractions per population and each was assayed four times with standard error of the mean

Fig. 5.

In vitro inhibition of AHAS activity by pyribenzoxim. Susceptible (S) and resistant (R) Limnocharis flava populations. Data were averaged from three extractions per population and each was assayed four times with standard error of the mean

Table 3.

Parameters of log-logistic analysis of the AHAS-herbicide concentration required to cause 50% inhibition of AHAS activity (I50) and the resistance index (RI) of susceptible (S) and resistant (R) Limnocharis flava populations

| Chemical class | Herbicide | Population | c | d | b | I50 | P | RI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (I50 R/ I50 S) | ||||||||

| Sulfonylurea | Bensulfuron-methyl | S | – | – | – | 0.0012* | < .0001 | |

| R | 0.00 | 98.86 | −0.21 | > 100 | < .0001 | > 83,333 | ||

| Metsulfuron-methyl | S | 1.85 | 100.36 | −0.34 | 0.0079 | < .0001 | ||

| R | 0.00 | 97.52 | −0.77 | 3.1484 | < .0001 | 398 | ||

| Pyrazosulfuron-ethyl | S | 2.47 | 99.67 | −0.30 | 0.0146 | < .0001 | ||

| R | 0.00 | 90.73 | −0.53 | 2.5162 | < .0001 | 172 | ||

| Pyrimidinyl(thio)benzoate | Pyribenzoxim | S | – | – | – | 0.9249* | < .0001 | |

| R | 0.00 | 92.39 | −1.28 | 44.632 | < .0001 | 48 |

Based on the log-logistic equation Y = c + {(d—c)/[1 + exp{b[log(x)—log I50]}, c is the lower limit, d is the upper limit, b is the slope and I50 is a concentration causing 50% inhibition. RI were calculated as the ratio of I50 values of resistant / I50 values of susceptible populations. Resistance levels were indicated by the resistance factor (RI). The I50 value with * was calculated from parameters obtained from exponential decay i.e. y = yo + ae−bx, where y0 is the lower limit, yo + a is the upper limit, b is the slope of the curve and x is the dose causing 50% response

Malathion did not reduce bensulfuron-methyl resistance level in L. flava

The potential co-existence of NTSR related to rapid/increased herbicide metabolism in R L. flava population carrying a resistant mutation of Asp-376-Glu was evaluated in a whole-plant dose–response using bensulfuron-methyl following application of malathion. It was found that the application of bensulfuron-methyl to R L. flava neither alone nor combination with malathion increased control of R L. flava. In the absence of bensulfuron-methyl, malathion treatment exhibited no adverse effect on the survival rate and shoot dry weight in both S and R L. flava populations. Preliminary, in the absence of bensulfuron-methyl, treatment of malathion only at recommended rate (2.25 L g ha−1) exhibited no adverse reaction on survival rate and shoot dry weight for both S and R L. flava populations (data not shown), eliminating the potential inhibitory effect of malathion on growth of L. flava. Comparably, when malathion was antecedently sprayed, no noteworthy reduction in plant growth following bensulfuron-methyl application was observed in R plants. Survival of R L. flava was high (> 80%) at all bensulfuron-methyl doses (Fig. 6), with resistance index (RI) values of 328-fold and 437-fold in the absence and presence of malathion, respectively (Table 4). This further indicates that a target-site as the primary mechanism to endow AHAS-resistance in the R L. flava. Meanwhile, the S L. flava was fully inhibited by half the recommended rate of bensulfuron-methyl, regardless of malathion combination.

Fig. 6.

Dose–response curves for (A) survival and (B) shoot dry weight of susceptible and resistant Limnocharis flava populations treated with a range of bensulfuron-methyl doses in the absence (-M) and presence (+ M) of cytochrome P450 inhibitor malathion (M). Each data point represents the mean percentage ± SE of three replications

Table 4.

LD50 and GR50 values of susceptible (S) and resistant (R) Limnocharis flava populations to bensulfuron-methyl in the absence and presence of cytochrome P450 inhibitor malathion

| Population | Bensulfuron-methyl (without malathion) | Bensulfuron-methyl (with malathion) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LD50 (g ai ha−1) | RI | GR50 | RIc | LD50 (g ai ha−1) | RI | GR50 | RI | |

| S | 3.41b | – | 5.78b | – | 2.56b | – | 5.78b | – |

| R | 1119.26a | 328.23 | 350.70a | 60.67 | 1119.26a | 437.21 | 121.52a | 21.02 |

LD50 is herbicide rate causing 50% mortality while GR50 is herbicide concentration causing 50% growth reduction of plants. RI (resistance index) were calculated as the ratio of LD50 or GR50 values of resistant / LD50 or GR50 values of susceptible population. Resistance levels were indicated by the resistance factor (RI). LD50 or GR50 values with different letters are significantly different at P < 0.05 by using LSD test

A slightly different growth response was observed in the R L. flava shoot dry weight following treatments of malathion and bensulfuron-methyl. When bensulfuron-methyl was applied alone, a 60-fold GR50 RI value was recorded, yet it was substantially reduced to almost 3 times lower (GR50 RI value of 21-fold) in the presence of malathion (Table 4 and Fig. 6). Evidently, all R plants that survived the application of malathion and bensulfuron-methyl exhibited a noticeable reduction in plant growth. This demonstrates that the combination of malathion with bensulfuron-methyl did affect the growth of R L. flava plants to a certain level, without affecting its survival. However, neither absence nor presence of malathion gave an effect to shoot dry weight of S L. flava (GR50 5.78), in which S L. flava was successfully controlled by bensulfuron-methyl below the recommended rate.

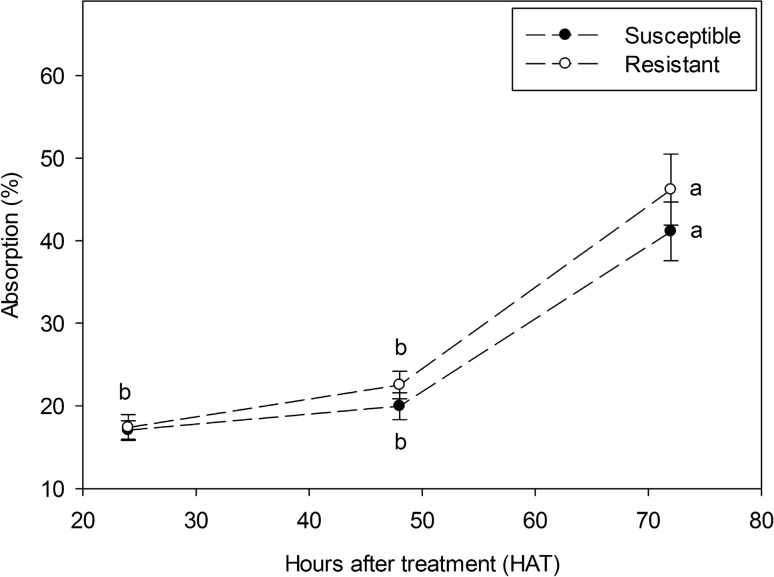

No evidence of differential bensulfuron-methyl absorption and translocation between the R and S L. flava

The absorption of bensulfuron-methyl in both R and S L. flava is gradually increased with time, but there is no observable difference of herbicide absorption between R and S plants at all harvesting times (HAT). There was a minor increment in the absorption rate from 24 and 48 HAT, later substantially elevated at 72 HAT (Fig. 7) to 41.13% and 46.20% in S and R plants, respectively. No notable difference between S and R L. flava populations on the absorption of bensulfuron-methyl was evident at all HAT, suggesting that differential rate of AHAS inhibitors did not confer resistance in the R L. flava.

Fig. 7.

Bensulfuron-methyl absorption at different hours after treatment in susceptible and resistant Limnocharis flava. The data points are mean ± standard error. Mean with the same letter is not significantly different at P < 0.05 between time intervals for each population

Translocation of bensulfuron-methyl in different parts of L. flava plants was examined in the stem of treated leaf (STL), stem of leaf above the treated leaf (SLATL), leaf above the treated leaf (LATL), stem of leaf below the treated leaf (SLBTL), and leaf below the treated leaf (LBTL) at different HAT. No apparent difference in the translocation rate was observed between S and R populations at all HAT in all plant parts (Table 5). Bensulfuron-methyl accumulated evenly in all plant parts between the R and S plants, further eliminating the possibility of reduced herbicide translocation in the R plants. Additionally, translocation of bensulfuron-methyl exhibited a positive correlation with the harvesting time in all plant parts for both populations, where the movement of herbicide was greater as the time increased (Table 5).

Table 5.

Main and interaction effects in bensulfuron-methyl accumulation (%) between population and hours after treatment (HAT) in different plant parts at 4–5-leaf-stage of susceptible (S) and resistant (R) Limnocharis flava

| Factors | LATL | LBTL | STL | SLATL | SLBTL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population (P) | |||||

| Susceptible | 10.27 ± 0.73a | 17.14 ± 1.28a | 13.78 ± 0.70a | 9.94 ± 0.90a | 13.77 ± 0.70a |

| Resistant | 11.43 ± 0.99a | 17.88 ± 1.02a | 13.73 ± 0.63a | 11.50 ± 2.41a | 14.00 ± 0.59a |

| Hours after treatment (HAT) | |||||

| 24 | 8.47 ± 0.28c | 14.75 ± 0.65b | 11.81 ± 0.23b | 8.42 ± 0.95b | 13.27 ± 0.86b |

| 48 | 10.56 ± 0.94b | 17.86 ± 0.97ab | 13.09 ± 0.56b | 11.68 ± 0.77a | 13.37 ± 0.56b |

| 72 | 13.53 ± 0.54a | 19.93 ± 1.58a | 16.36 ± 0.46a | 11.87 ± 0.87a | 15.01 ± 0.77a |

| P × HAT | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

Plant parts are in abbreviation: LATL, leaf above the treated leaf; LBTL, the leaf below the treated leaf; STL, the stem of treated leaf; SLATL, the stem of leaf above the treated leaf; SLBTL, the stem of leaf below the treated leaf. Means within a column followed by the same letter are not significantly different by least significant different test (LSD) at P ≤ 0.05. ns is not significant

Table 6 illustrates the distribution (%) of bensulfuron-methyl in different parts of R and S L. flava at 24, 48, and 72 HAT following application. Bensulfuron-methyl was transported bidirectionally to LATL, LBTL, STL, SLATL, and SLBTL, although it was noticed that at all HATs, the accumulation of bensulfuron-methyl was always higher in LBTL as compared to other parts, in both R and S plants (Table 6). These positive correlations among different plant parts suggested that bensulfuron-methyl was transported to both upper and lower parts of L. flava from the application point following application, but at different rates.

Table 6.

Percentage (%) of bensulfuron-methyl accumulation in different plant parts of susceptible (S) and resistant (R) Limnocharis flava at different hours after treatment (HAT)

| Plant parts | Susceptible | Resistant | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 HAT | 48 HAT | 72 HAT | Mean | 24 HAT | 48 HAT | 72 HAT | Mean | |

| LATL | 8.06 ± 0.4b | 9.92 ± 0.6b | 12.84 ± 0.3b | 10.27 ± 0.7c | 8.88 ± 0.3b | 11.20 ± 1.9c | 14.22 ± 0.9b | 11.43 ± 1.0c |

| LBTL | 13.90 ± 0.7a | 17.18 ± 1.0a | 20.31 ± 2.8a | 17.14 ± 1.3a | 15.57 ± 0.9a | 18.53 ± 1.8a | 19.55 ± 2.0a | 17.88 ± 1.0a |

| STL | 12.07 ± 0.3a | 15.03 ± 0.7a | 16.23 ± 0.9a | 14.45 ± 0.7b | 13.15 ± 0.3a | 15.88 ± 0.8ab | 16.49 ± 1.0bc | 15.17 ± 0.6b |

| SLATL | 7.20 ± 0.3b | 10.72 ± 1.2b | 11.88 ± 1.4b | 9.94 ± 0.9c | 9.64 ± 1.7b | 11.86 ± 0.4c | 13.01 ± 1.2c | 11.50 ± 0.8c |

| SLBTL | 12.33 ± 1.3a | 13.07 ± 0.6ab | 15.89 ± 0.4a | 13.77 ± 0.7b | 13.66 ± 1.3a | 14.13 ± 0.6bc | 14.21 ± 1.4b | 14.00 ± 0.6b |

Plant parts are in abbreviation: LATL, leaf above the treated leaf; LBTL, the leaf below the treated leaf; STL, the stem of treated leaf; SLATL, the stem of leaf above the treated leaf; SLBTL, the stem of leaf below the treated leaf. Means with the same letter in the column are not significantly different according to LSD test at P < 0.05

Discussion

This finding established AHAS target-site mutation as the basis of mechanism endowing resistance in the R L. flava population. A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) (GAC to GAG) in the R plants AHAS gene, which possesses mutated AHAS gene resulting in a substitution of Asp for Glu in Domain F of AHAS gene at position 376 was observed in all R L. flava individuals, in comparison to the GAC in the S plants (Table 2). The Asp-376-Glu mutation has been reported in other weed species worldwide in the last decade such as Amaranthus powellii S. Wats. in Ontario (Ashigh et al. 2009), Amaranthus hybridus L. in Pennsylvania (Whaley et al. 2007), Raphanus raphanistrum L. in Western Australia (Yu et al. 2012), Conyza canadensis (L.) Cronquist in Indiana (Zheng et al. 2011), Schoenoplectus juncoides (Roxb.) Palla in Japan (Sada et al. 2013), Galium spurium L. in western Canada (Beckie et al. 2012) and Kochia scoparia (L.) Schrader in western Canada (Warwick et al. 2008). The present study has added Limnocharis flava from Malaysia into this group of mutation and the first report on the mechanism endowing resistance in Malaysian rice weeds. Earlier studies have shown that AHAS mutations at Asp-376 usually confer broad-spectrum resistance to many AHAS inhibitors in weed species worldwide (Powles and Yu 2010; Tranel et al. 2017). This is also true in the current finding, where all the R L. flava plants harbouring the Asp-376-Glu were cross-resistant to AHAS-inhibitors group SU (bensulfuron-methyl, pyrazosulfuron-ethyl, metsulfuron-methyl) at higher level as compared to the PTB group (pyribenzoxim) in the whole-plant dose–response study (Zakaria et al. 2018). This is not surprising, since farmers have been depending on SU herbicides, particularly bensulfuron-methyl for control of L. flava in their rice fields since the early 1990s, whereas the implementation of other AHAS inhibitors as an alternative chemical approach was rather more recent (less than 7 years). Similarly, higher resistance levels to SU herbicides over the other AHAS-inhibitor groups in weed species carrying Asp-376-Glu have been reported by Yu et al. (2012), Sada et al. (2013), and Deng et al. (2016).

The AHAS in vitro activity studies established that the resistance mechanism in R L. flava population was mainly due to AHAS high insensitivity to the SU group pyrazosulfuron-ethyl, metsulfuron-methyl, and bensulfuron-methyl, and little to the PTB group pyribenzoxim., which have been reported in various weed species such as S. mucronatus, S. juncoides, Lindernia spp. or M. vaginalis (Kuk et al. 2003a; Calha et al. 2007). This is the first report on the occurrence of target-site resistance to AHAS inhibitors in L. flava. The common rice IMI, TP herbicides and another PTB bispyribac-sodium were not tested for enzyme inhibition due to these herbicides successfully controlled R L. flava at recommended dose in the whole-plant dose–response experiment (Zakaria et al. 2018), while SCT was not included in this experiment due to this herbicide is not registered in Malaysia for rice weeds control. The cross-resistance pattern at the protein level endowed by the Asp-376-Glu mutation in the R L. flava was also comparable with other weed species carrying the same mutation, for instance, Ashigh et al. (2009) found that AHAS enzyme inhibition assay (I50) of A. powellii conferred high level of resistance to the SU (thifensulfuron-methyl), PTB (pyrithiobac), SCT (flucarbazone) and TP (flumetsulam) with resistance index (RI) ranging from 485-fold to 132-fold, respectively. In a study conducted on A. hybridus (Whaley et al. 2007), it was observed that the resistance factors of GR50 (RF = 1300–3261) were much higher to the herbicides in SU class (thifensulfuron and chlorimuron) than to other classes. Likewise, the determination of 50% enzyme inhibition (I50) in SU class for metsulfuron-methyl, bensulfuron-methyl, and imazosulfuron, were 322, 2438, and 3699, respectively which was higher than pyrimidinyl(thio)benzoate (PTB) (bispyribac-sodium) and IMI herbicide (imazaquin) with RI values of 80 and 4.8, respectively as observed in S. juncoides (Sada et al. 2013). In this findings, the R L. flava conferred high level of resistance to SU (pyrazosulfuron-ethyl, metsulfuron-methyl, and bensulfuron-methyl) with RI ranging from 172 to > 83,333, whilst exhibiting a lower resistance level to PTB (pyribenzoxim) (RI = 48).

These distinct resistance patterns at molecular and enzyme levels endowed by the R L. flava population to different AHAS inhibitors can possibly be explained by plant AHAS structure modelling. As reviewed by Yu and Powles (2014), the substitution of amino acid Pro-197 by Ala, Asn, Arg, His, Leu, Thr, Gln, Met, Ser, Ile, Lys, or Trp have been reported having resistance to SU herbicides. Remarkably, 12 amino acid substitutions can confer herbicide resistance in AHAS at Pro-197, where this position is the most often identified mutation than other amino acid positions (Heap 2021). However, mutation at Pro-197 was not found in the R L. flava population even though this population possesses high resistance level to SU herbicides. As suggested by Duggleby et al. (2008) and McCourt et al. (2006), further discussed by Yu and Powles (2014), different AHAS inhibitors possess different chemical structures that would orientate differently in the herbicide binding domain, even though the herbicides are from the same family. The binding sites of SU, PTB, SCT, TP, and IMI herbicides are probably overlapping but not identical. Perhaps, many SU herbicides strongly overlap in the binding site at the 376 position in the AHAS gene, which consequently trigger Asp-to-Glu mutation at this 376 position. This would explain the high resistance levels to the SU group expressed by the R L. flava and other weed species associated with the Asp-376-Glu mutation.

In Malaysia, 16 weeds have been reported resistant to various herbicide modes of action such as PSI electron diverter, synthetic auxin, ACCase inhibitors, EPSP synthase inhibitor, AHAS inhibitors, PSII inhibitors, glutamine synthase inhibitors, and among these modes of action, six weeds were reported resistant to AHAS inhibitors (Tranel et al. 2017; Heap 2021). Currently reported AHAS herbicide resistant weeds in Malaysia are Limnocharis flava, Sagittaria guayanensis Kunth, Bacopa rotundifolia (Michx.) Wettst., Limnophila erecta Benth., and Clidemia hirta (L.) D. Don, and the most recent weedy rice (Oryza sativa L. complex) (Ruzmi et al. 2017; Heap 2021). It is likely that Asp-376 mutation (as well as other AHAS mutations) is also present in other AHAS-resistant weed species and conducive studies need to be conducted in order to identify this AHAS mutation.

Malathion is an organophosphorus insecticide, widely used for control of variety agriculture and residential landscaping pest insects including mosquito. With respect to application concentration, malathion has been opined capable to inactivate cytochrome P450 monooxygenases involved in rapid metabolism of AHAS inhibitors, and commonly adopted to evaluate AHAS metabolic resistance mechanisms, as well as reduction in crop tolerance to AHAS inhibitors (Owen et al. 2012; Yu and Powles 2014; Brosnan et al. 2016). The synergistic interaction possessed by the organophosphate insecticides to inhibit the cytochrome P450 activity and increased herbicide efficacy, have been well evaluated in various weed species (Yu et al. 2003; Owen et al. 2012). Nonetheless, we did not observe any reduction in RI value when R individuals were treated with malathion prior to bensulfuron-methyl application, where the combination of malathion and bensulfuron-methyl was impotent to decrease the mortality of R L. flava, having RI value 437-fold, as compared to a lower 328-fold when bensulfuron-methyl was applied alone. Similarly, Brosnan et al. (2016) reported the non-existence of NTSR in an AHAS-resistant annual bluegrass (Poa annua (L.) POAAN-R3) when treated with two different cytochrome P450 inhibitors malathion and piperonyl butoxide (PBO) prior to the application of several AHAS inhibitors.

Plant cytochrome P450s are diverse superfamily enzymes, playing paramount roles in synthesis of many secondary metabolites, and metabolism of toxic herbicides and insecticides into reduced toxicity compounds (Siminszky 2006). An evolved metabolic P450-based herbicide resistance in L. rigidum has been associated with a reduction in plant fitness (Powles and Yu 2010). Although malathion did not increase control of R plants by bensulfuron-methyl, a significant reduction in shoot dry weight in R L. flava plants bearing the AHAS Asp-376-Glu mutation, following application of malathion and bensulfuron-methyl as compared to bensulfuron-methyl alone, more or less, illustrates possible fitness penalty in growth. Nonetheless, the effect of malathion in reducing the growth of R L. flava was not permanent. Following plant harvest at 1 cm aboveground in order to get the dry weight, and later the R plants were allowed to grow back, all the herbicide-treated R L. flava plants (with and without malathion) regrew rapidly, having almost the same height as the untreated R. It is hence interesting to investigate the growth-fitness effect of malathion on other AHAS-resistant weed species, as a future indication in combating herbicide resistant weed species in Malaysia.

Bensulfuron-methyl is a sulfonylurea herbicide that inhibits acetohydroxyacid synthase (AHAS), an enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of branched-chain amino acids isoleucine, leucine, and valine crucial for protein development in new cells. Bensulfuron-methyl is a systemic and versatile herbicide; applied as pre- and post-emergence, subjected to both root and shoot uptake, moving in both apoplastic (xylem) and symplastic (phloem), and accumulates in the meristematic tissues (Mabury et al. 1996; FAO 2002). In Malaysia, bensulfuron-methyl is commonly applied either individually in rice fields and landscape/turfgrass fields, or tank-mixed with glyphosate to increase control of semi woody broadleaf weeds in oil palm plantations. The gradual upsurge in bensulfuron-methyl penetration in L. flava plants from 24 to 72 HAT in this study is in agreement with findings on different herbicide sites of action. It was reported that the absorption of cyhalofop-butyl (ACCase inhibitor) by Echinochloa crus-galli (L.) Beauv was greater at 72 HAT than shorter time intervals (2, 6, 24, and 48 HAT) (Li et al. 2016). Similarly, a significant increase in the absorption of topramezone from 2 to 48 HAT by Setaria faberi Herrm. and Abutilon theophrasti Medic. was recorded, regardless the use of adjuvant (Zhang et al. 2013).

Although the NTSR of reduced herbicide penetration has been numerously reported in the resistant weed species to glyphosate, AHAS inhibitors, and ACCase inhibitors (Délye 2013) contrastively all the R L. flava individuals in the current study, which have evolved resistant to AHAS inhibitors since 1998 do not possess such resistance mechanism. Likewise, bensulfuron-methyl was equally quantified in all harvested plant parts, namely upper and lower stems and leaves at 24, 48, and 72 HAT following herbicide treatment for both S and R plants. Thus, the co-existence of reduced translocation of AHAS inhibitors was also unlikely to occur in the R L. flava, similar to several findings in other AHAS-inhibitor weed species which indicated that resistance was rather conferred by either mutation(s) at the binding site or enhanced herbicide metabolism (Veldhuis et al. 2000; Hatami et al. 2016).

Conclusions

In conclusion, this investigation reveals highly insensitive AHAS enzyme towards AHAS-inhibitors, endowed by Asp-376-Glu mutation in the AHAS gene. Both S and R L. flava populations exhibited comparable bensulfuron-methyl absorption, translocation, and metabolism ability, indicating the unlikeliness of NTSR mechanisms in the L. flava R population towards AHAS inhibitors. Nonetheless, the observable reduction in shoot dry weight following malathion + bensulfuron-methyl application warrants further investigations on the role of malathion in influencing plant growth in the AHAS-resistant L. flava. Identifying the resistance mechanisms to AHAS inhibitors not only provides the knowledge of understanding the mechanism in other plants, but also aids in the weed management specifically in management of herbicide-resistant weed species by diagnosing less resistance-prone alternative herbicide preferences for farmers, especially in Malaysia where the application of AHAS inhibitors is prevalent. An ever increasing in the number of herbicide resistant weed populations towards AHAS inhibitors worldwide, not to be excluded Malaysia needs to be frequently monitored, and more researches on effective and sustainable herbicide-resistant weed management are crucially needed. The integrated weed management and herbicide rotation have always been repeatedly highlighted by many researchers as the best long-term strategy to sustain herbicide efficacy, and proactively improve on the management of herbicide resistant weed species worldwide.

Acknowledgements

This research project received financial support from the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme FRGS/1/2014/STWN03/UPM/02/8: 07-01-04/1440FR (5524524) under the Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia.

Abbreviations

- AHAS

Acetohydroxyacid synthase

- IMI

Imidazolinones

- PTB

Pyrimidinyl(thio)benzoates

- R

AHAS-inhibitor resistant

- RI

Resistance index

- S

AHAS-inhibitor susceptible

- SCT

Sulfonylaminocarbonyl-triazolinones

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- SU

Sulfonylureas

- TP

Triazolopyrimidine sulfonanilides

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study (AHAS gene nucleotide sequence obtained from sequencing of AHAS-inhibitor susceptible L. flava) are openly available in the public domain NCBI GenBank database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucleotide/) with accession number KX891189.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ashigh J, Corbett CAL, Smith PJ, Laplante J, Tardif FJ. Characterization and diagnostic tests of resistance to acetohydroxyacid synthase inhibitors due to an Asp376Glu substitution in Amaranthus powellii. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2009;95:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2009.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beckie HJ, Warwick SI, Sauder CA, Kelln GM, Lozinski C. Acetolactate synthase inhibitor-resistant false cleavers (Galium spurium) in Western Canada. Weed Technol. 2012;26:151–155. doi: 10.1614/WT-D-11-00075.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosnan JT, Vargas JJ, Breeden GK, Grier L, Aponte RA, Tresch S, Laforest MM. A new amino acid substitution (Ala-205-Phe) in acetolactate synthase (ALS) confers broad spectrum resistance to ALS-inhibiting herbicides. Planta. 2016;243:149–159. doi: 10.1007/s00425-015-2399-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busi R, Vidotto F, Fischer AJ. Patterns Of Resistance To ALS Herbicides In Smallflower Umbrella Sedge (Cyperus Difformis) And Ricefield Bulrush (Schoenoplectus Mucronatus) L. Weed Technol. 2006;20:1004–1014. doi: 10.1614/WT-05-178.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- CABI (2013) Invasive Species Compendium. Wallingford, UK: CAB International. Available at www.cabi.org/isc.

- Calha IM, Osuna MD, Serra C, Moreira I, De Prado R, Rocha F. Mechanism of resistance to bensulfuron-methyl in Alisma plantago-aquatica biotypes from Portuguese rice paddy fields. Weed Res. 2007;47:231–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3180.2007.00558.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Délye C. Unravelling the genetic bases of non-target-site-based resistance (NTSR) to herbicides: a major challenge for weed science in the forthcoming decade. Pest Manag Sci. 2013;69:176–187. doi: 10.1002/ps.3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng W, Yang Q, Jiao HT, Zhang YZ, Li XF, Zheng MQ. Cross-resistance pattern to four AHAS-inhibiting herbicides of tribenuron-methyl-resistant flixweed (Descurainia sophia) conferred by Asp-376-Glu mutation in AHAS. J Integr Agr. 2016;15:2563–2570. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(16)61432-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duggleby RG, Mccourt JA, Guddat LW. Structure and mechanism of inhibition of plant acetohydroxyacid synthase. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2008;46:309–324. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO (2002) FAO Specifications and Evaluations for Plant Protection Products. Nations, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United 1–20

- Grabherr M, Haas B, Yassour M, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakim MA, Juraimi AS, Ismail MR, Hanafi MM, Selamat A. A survey on weed diversity in coastal rice fields of sebarang Perak in Peninsular Malaysia. J Anim Plant Sci. 2013;23:534–542. [Google Scholar]

- Hatami ZM, Gherekhloo J, Rojano-Delgado AM, Osuna MD, Fernández R, Sadeghipour HR, De Prado R. Multiple mechanisms increase levels of resistance in Rapistrum rugosum to ALS herbicides. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heap I (2021) The International Survey of Herbicide-Resistant Weeds. Available at www.weedscience.org.

- Iwakami S, Watanabe H, Miura T, Matsumoto H, Uchino A. Occurrence of sulfonylurea resistance in Sagittaria trifolia, a basal monocot species, based on target-site and non-target-site resistance. Weed Biol Manag. 2014;14:43–49. doi: 10.1111/wbm.12031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Juraimi AS, Begum M, Parvez Anwar M, Shari ES, Sahid I, Man A. Controlling resistant Limnocharis flava (L.) Buchenau biotype through herbicide mixture. J Food Agric Environ. 2012;10:1344–1348. [Google Scholar]

- Karim RS, Man AB, Sahid IB. Weed problems and their management in rice fields of Malaysia: an overview. Weed Biol Manag. 2004;4:177–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-6664.2004.00136.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuk YI, Jung HI, Kwon OD, Lee DJ, Burgos NR, Guh JO. Sulfonylurea herbicide-resistant Monochoria vaginalis in Korean rice culture. Pest Manag Sci. 2003;59:949–961. doi: 10.1002/ps.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuk YI, Kim KH, Kwon OD, Lee DJ, Burgos NR, Jung S, Guh JO. Cross-resistance pattern and alternative herbicides for Cyperus difformis resistant to sulfonylurea herbicides in Korea. Pest Manag Sci. 2003;60:85–94. doi: 10.1002/ps.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Chen W, Xu Y, Wu X. Comparative effects of different types of tank-mixed adjuvants on the efficacy, absorption and translocation of cyhalofop-butyl in barnyardgrass (Echinochloa crus-galli [L.] Beauv.) Weed Biol Manag. 2016;16:80–89. doi: 10.1111/wbm.12095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mabury S, Cox J, Crosby D. Environmental fate of rice pesticides in California. Rev Environ Contam Toxicol. 1996;147:71–177. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4612-4058-7_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathloob A, Khaliq A, Chauhan BS. Chapter five—weeds of direct-seeded Rice in Asia: problems and opportunities. Adv Agron. 2015;130:291–336. doi: 10.1016/bs.agron.2014.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCourt JA, Pang SS, King-Scott J, Guddat LW, Duggleby RG. Herbicide-binding sites revealed in the structure of plant acetohydroxyacid synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103:569–573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508701103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merotto A, Jasieniuk M, Osuna MD, Vidotto F, Ferrero A, Fischer AJ. Cross-resistance to herbicides of five ALS-inhibiting groups and sequencing of the ALS gene in Cyperus difformis L. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:1389–1398. doi: 10.1021/jf802758c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osuna MD, Vidotto F, Fischer AJ, Bayer DE, De Prado R, Ferrero A. Cross-resistance to bispyribac-sodium and bensulfuron-methyl in Echinochloa phyllopogon and Cyperus difformis. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2002;73:9–17. doi: 10.1016/S0048-3575(02)00010-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Owen MJ, Goggin DE, Powles SB. Non-target-site-based resistance to ALS-inhibiting herbicides in six Bromus rigidus populations from Western Australian cropping fields. Pest Manag Sci. 2012;68:1077–1082. doi: 10.1002/ps.3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powles SB, Yu Q. Evolution in action: plants resistant to herbicides. Ann Rev Plant Biol. 2010;61:317–347. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riar DS, Tehranchian P, Norsworthy J, Nandula V, McElroy S, Srivastava V, Chen S, Bond J, Scott RC. Acetolactate Synthase-Inhibiting Herbicide-Resistant Rice Flatsedge (Cyperus iria): Cross Resistance and Molecular Mechanism of Resistance. Weed Sci. 2015;63:748–757. doi: 10.1614/WS-D-15-00014.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzmi R, Ahmad-Hamdani MS, Bakar B. Prevalence of herbicide-resistant weed species in Malaysian rice fields: a review. Weed Biol Manag. 2017;17:1–14. doi: 10.1111/wbm.12112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sada Y, Ikeda H, Yamato S, Kizawa S. Characterization of sulfonylurea-resistant Schoenoplectus juncoides having a target-site Asp376Glu mutation in the acetolactate synthase. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2013;107:106–111. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seefeldt SS, Jensen JE, Fuerst EP. Log-logistic analysis of herbicide dose-response relationships. Weed Technol. 1995;9:218–227. doi: 10.1017/S0890037X00023253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siminszky B. Plant cytochrome P450-mediated herbicide metabolism. Phytochem Rev. 2006;5:445–458. doi: 10.1007/s11101-006-9011-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tardif FJ, Rajcan I, Costea MA. A mutation in the herbicide target-site acetohydroxyacid synthase produces morphological and structural alterations and reduces fitness in Amaranthus powellii. New Phytol. 2006;169:251–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tranel PJ, Wright TR. Resistance of weeds to ALS-inhibiting herbicides: what have we learned? Weed Sci. 2002;50:700–712. doi: 10.1614/0043-1745(2002)050[0700:RROWTA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tranel P, Wright T, Heap I (2017) Mutations in herbicide-resistant weeds to ALS inhibitors. http://www.weedscience.com. Accessed 21 Jan 2020

- Veldhuis LJ, Hall LM, O’Donovan JT, Dyer W, Hall JC. Metabolism-based resistance of a wild mustard (Sinapis arvensis L.) biotype to ethametsulfuron-methyl. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:2986–2990. doi: 10.1021/jf990752g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warwick SI, Xu R, Sauder C, Beckie HJ. Acetolactate Synthase Target-Site Mutations and Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Genotyping in ALS-Resistant Kochia (Kochia scoparia) Weed Sci. 2008;56:797–806. doi: 10.1614/WS-08-045.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse BM, Mitchell AA (1998) Northern Australia Quarantine Strategy: Weeds Target List. Agriculture Western Australia

- Weber JM, Brooks SJ. The biology of Australian weeds 62. Limnocharis flava (L.) Buchenau. Plant Prot Q. 2013;28:101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Wei S, Li P, Ji M, Dong Q, Wang H. Target-site resistance to bensulfuron-methyl in Sagittaria trifolia L. populations. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whaley CM, Wilson HP, Westwood JH. A new mutation in plant ALS confers resistance to five classes of ALS-Inhibiting herbicides. Weed Sci. 2007;55:83–90. doi: 10.1614/WS-06-082.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Deng W, Li X, Yu Q, Bai L, Zheng M. Target-site and non-target-site based resistance to the herbicide tribenuron-methyl in flixweed (Descurainia sophia L.) BMC Genom. 2016;17:551–564. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2915-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q, Powles SB. Resistance to AHAS inhibitor herbicides: current understanding. Pest Manag Sci. 2014;70:1340–1350. doi: 10.1002/ps.3710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q, Han H, Vila-Aiub MM, Powles SB. AHAS herbicide resistance endowing mutations: effect on AHAS functionality and plant growth. J Exp Bot. 2010;61:3925–3934. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q, Zhang XQ, Hashem A, Walsh MJ, Powles SB. ALS gene proline (197) mutations confer ALS herbicide resistance in eight separated wild radish (Raphanus raphanistrum) populations. Weed Sci. 2003;51:831–838. doi: 10.1614/02-166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q, Han H, Li M, Purba E, Walsh MJ, Powles SB. Resistance evaluation for herbicide resistance-endowing acetolactate synthase (ALS) gene mutations using Raphanus raphanistrum populations homozygous for specific ALS mutations. Weed Res. 2012;52:178–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3180.2012.00902.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zakaria N, Ahmad-Hamdani MS, Juraimi AS. Patterns of Resistance to AHAS Inhibitors in Limnocharis flava from Malaysia. Plant Prot Sci. 2018;54:48–59. doi: 10.17221/131/2016-PPS. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Jaeck O, Menegat A, Zhang Z, Gerhards R, Ni H. The mechanism of methylated seed oil on enhancing biological efficacy of topramezone on weeds. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:2–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng D, Kruger GR, Singh S, Davis VM, Tranel PJ, Weller SC, Johnson WG. Cross-resistance of horseweed (Conyza canadensis) populations with three different ALS mutations. Pest Manag Sci. 2011;67:1486–1492. doi: 10.1002/ps.2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study (AHAS gene nucleotide sequence obtained from sequencing of AHAS-inhibitor susceptible L. flava) are openly available in the public domain NCBI GenBank database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucleotide/) with accession number KX891189.