Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a major impact on healthcare in many countries. This study assessed the effect of a nationwide lockdown in France on admissions for acute surgical conditions and the subsequent impact on postoperative mortality.

Methods

This was an observational analytical study, evaluating data from a national discharge database that collected all discharge reports from any hospital in France. All adult patients admitted through the emergency department and requiring a surgical treatment between 17 March and 11 May 2020, and the equivalent period in 2019 were included. The primary outcome was the change in number of hospital admissions for acute surgical conditions. Mortality was assessed in the matched population, and stratified by region.

Results

During the lockdown period, 57 589 consecutive patients were admitted for acute surgical conditions, representing a decrease of 20.9 per cent compared with the 2019 cohort. Significant differences between regions were observed: the decrease was 15.6, 17.2, and 26.8 per cent for low-, intermediate- and high-prevalence regions respectively. The mortality rate was 1.92 per cent during the lockdown period and 1.81 per cent in 2019. In high-prevalence zones, mortality was significantly increased (odds ratio 1.22, 95 per cent c.i. 1.06 to 1.40).

Conclusion

A marked decrease in hospital admissions for surgical emergencies was observed during the lockdown period, with increased mortality in regions with a higher prevalence of COVID-19 infection. Health authorities should use these findings to preserve quality of care and deliver appropriate messages to the population.

This study assessed the change in acute surgical conditions during the lockdown period on a nationwide scale. There was an overall reduction in emergency operations of 20.9 per cent, with great variability according to prevalence of COVID-19 admissions. Mortality increased in regions with a high prevalence of COVID-19 infection.

Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2; COVID-19) pandemic has had profound effects on healthcare systems globally. Hospitals, in particular, have been overwhelmed by the massive influx of infected patients. To cope with the burden of disease, hospital workforce was reallocated and elective surgery significantly delayed. Various countries implemented a national lockdown, with major restrictions on all non-essential travel outside the home. In France, an initial lockdown was declared from 17 March to 11 May 20201.

Few studies have reported on the impact on emergency department visits for acute illnesses not related to COVID-19 during the lockdown period, although decreased attendances have been described for myocardial infarction, trauma, and acute gastrointestinal conditions including appendicitis and acute cholecystitis1–4.

Although individual centres and specialties rapidly identified the impact of COVID-19 on surgical services, there remains a lack of information on its effect on emergency surgery at a nationwide level during lockdown.

This study investigated how the sudden disruption of usual healthcare during the lockdown period affected acute surgery. The aim was to quantify changes in hospital admissions for emergency surgical conditions according to the regional prevalence of COVID-19, comparing the lockdown period with the same time interval in 2019. Potential changes in mortality were investigated.

Methods

This was an observational, analytical study of the impact of a national lockdown during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on the rate of surgical emergencies. Data were extracted from a national discharge database, the Programme De Médicalisation des Systèmes d’Information (PMSI), which collects all discharge reports from all hospitals in France, irrespective of facility ownership or academic affiliation. Discharge reports are mandatory and represent the basis for hospital funding. The database is comprehensive for all reimbursed surgical interventions in the country.

Data collected included patient demographics (age, sex, postal code, admission and discharge dates) along with primary and associated diagnoses based on ICD-10.

Participants

All adult patients aged at least 18 years admitted during the period of lockdown between 17 March and 11 May 2020 and the equivalent period in 2019 (19 March and 13 May) were considered. Patients were identified in the database through the diagnosis-related group classification, used to identify any hospital stay in which a surgical event occurred. Only emergency admissions were considered, defined as any admission passing through the emergency department. In the case of multiple admissions for the same patient, all hospital stays were included.

Exposures and confounders

The exposure variable was the year of admission, 2019 versus 2020, the year 2019 being the reference group. Potential confounders in readmission destination were assessed at several levels. Baseline patient characteristics included age, sex, BMI, and co-morbidities, according to the Charlson Co-morbidity Index (using Bannay weighting)5.

Regional differences were based on the reported ratios of hospital admissions for COVID-19 infection per 100 000 inhabitants. Three regional groups were established based on the numbers of admissions: 30 or more per 100 000 in high-prevalence regions, 15–29 per 100 000 in intermediate-prevalence regions, and fewer than 15 per 100 000 in low-prevalence regions2.

In the ICD-10 catalogue, diagnosis codes have a hierarchical classification in four levels6 based on 22 chapters, each using a letter code. Each chapter is divided into blocks of homogenous three-character categories (for instance, codes K35–K38 represent diseases of appendix). In this study, these two first levels of classification are referred to as chapters and blocks. Within each block, ICD-10 codes are classified into three-character categories (K35 represents acute appendicitis) and four-character subcategories (K35.2 represents acute appendicitis with generalized peritonitis), defining disease characteristics in increased detail. In this study, the last four-character level is referred to as a subcategory.

In the present study, 90 per cent of the most frequent diagnoses using the four-character subcategories of ICD-10 codes were selected, reducing the number of diagnoses from over 10 000 to approximately 500. Complete attrition is reported in Fig.S1.

Outcomes

The main outcome of this study was the rate of admission for adult surgical emergencies during the lockdown period in France compared with the same interval in 2019. A secondary outcome was in-hospital mortality after admission. Mortality was assessed irrespective of the time between the day of admission and death. The impact of active SARS-CoV-2 infection on mortality was assessed in a subgroup analysis.

Data access and linkage

In the PMSI database, each patient is assigned a unique identifier, which remains unchanged over time, making linkage between hospital stays in different hospitals possible. Because the identifier is anonymous, patient consent was not required. Access to the database was submitted for authorization by the National Commission on Informatics and Liberty (authorization number 01947391).

Statistical analysis

The balance among patient co-variables was assessed using standardized mean differences (SMDs); a difference of 10 per cent or less was considered a well balanced result7. The paired-samples Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to examine the difference in median number of emergencies between lockdown and control periods.

Potential confounders among measured co-variables were assessed by propensity score analysis. The probability of each patient being admitted during the lockdown was calculated by logistic regression incorporating all patient variables. Matching between the lockdown and control groups was performed using the nearest neighbour for propensity score and the exact method for the diagnosis code (using the 3-character category), sex, and age group. In the matched cohort, the balance between co-variables was also assessed using the SMD. Mortality odds ratios (ORs) for each surgical disease were estimated by means of a logistic univariable regression model.

A similar method was used to calculate the OR for mortality associated with COVID-19. Patients with COVID-19 from the lockdown period were matched with those admitted during the same interval using the propensity score, as described above. An adjusted OR for mortality with confidence interval was calculated using the logistic regression model. All statistical analyses were done with R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

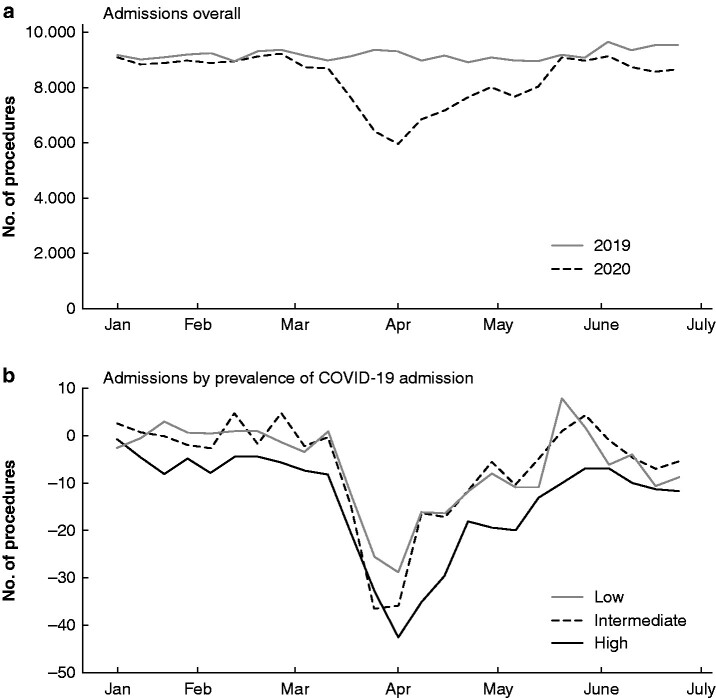

During the lockdown, 57 589 emergency surgical admissions occurred in France, representing a decrease of 20.9 per cent compared with the same period in 2019 (72 819 admission). The nadir of admissions was observed during week 12 (–36.1 per cent), followed by gradual increases, until the first week after the end of lockdown (week 20), when the difference between 2019 and 2020 was negligible (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Acute surgical admissions

a Overall and b according to regional prevalence of COVID-19 admission. The shaded area represents the period of lockdown in 2020.

The decrease in emergency surgical admissions differed between regions, reflecting the overall prevalence of admissions for COVID-19 infection. This amounted to 15.6 and 17.2 per cent decreases for low- and intermediate-prevalence regions respectively, with a 26.8 per cent decrease for high-prevalence regions where the nadir in week 13 was 42.3 per cent (Fig. 1b).

The characteristics of patients admitted during the lockdown were similar to those of patients admitted during the same interval in 2019, with a mean(?) SMD of 0.015(0.013); no co-variable had a SMD larger than 0.100 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

|

Control group (2019)

(n = 72 819) |

Lockdown group (2020)

(n = 57 589) |

SMD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 56.49(23.08) | 57.34(23.01) | 0.037 |

| < 30 | 13 104 (18.0) | 9461 (16.4) | |

| 30–39 | 10 611 (14.6) | 8744 (15.2) | |

| 40–49 | 7203 (9.9) | 5658 (9.8) | |

| 50–59 | 8127 (11.2) | 6318 (11.0) | |

| 60–75 | 14 294 (19.6) | 11 178 (19.4) | |

| > 75 | 19 501 (26.8) | 16 230 (28.2) | |

| Women | 40 452 (55.5) | 32 466 (56.4) | 0.017 |

| Charlson Co-morbidity Index score* | 0.42 (0.87) | 0.44 (0.89) | 0.026 |

| 0 | 54 382 (74.7) | 42 275 (73.4) | |

| 1–2 | 15 578 (21.4) | 12 856 (22.3) | |

| >3 | 2880 (4.0) | 2458 (4.3) | |

| Myocardial infarction | 875 (1.2) | 676 (1.2) | 0.003 |

| Congestive heart failure | 3698 (5.1) | 3140 (5.5) | 0.017 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 2046 (2.8) | 1738 (3.0) | 0.012 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1700 (2.3) | 1352 (2.3) | 0.001 |

| Dementia | 3027 (4.2) | 2393 (4.2) | <0.001 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 2413 (3.3) | 2228 (3.9) | 0.030 |

| Rheumatic disease | 350 (0.5) | 300 (0.5) | 0.006 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 427 (0.6) | 317 (0.6) | 0.005 |

| Mild liver disease | 684 (0.9) | 608 (1.1) | 0.012 |

| Diabetes without chronic complication | 5172 (7.1) | 4276 (7.4) | 0.013 |

| Diabetes with chronic complication | 1399 (1.9) | 1009 (1.8) | 0.013 |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia | 1281 (1.8) | 1014 (1.8) | <0.001 |

| Renal disease | 2518 (3.5) | 2119 (3.7) | 0.012 |

| Any malignancy, including lymphoma and leukaemia, except malignant neoplasm of skin | 3330 (4.6) | 2933 (5.1) | 0.024 |

| Moderate or severe liver disease | 156 (0.2) | 154 (0.3) | 0.011 |

| Metastatic solid tumour | 1321 (1.8) | 1119 (1.9) | 0.01 |

| AIDS/HIV | 81 (0.1) | 54 (0.1) | 0.005 |

| Obesity | 3588 (4.9) | 3026 (5.3) | 0.015 |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise; *values are mean(s.d.). SMD, standardized mean difference; AIDS/HIV, acquired immune deficiency syndrome/human imuunodeficiency virus.

Trends in admission by chapter and category are reported in Table 2. The decrease in number of emergency admissions affected all chapters, except other reasons for admission, where numbers were relatively small. Admissions related to the injury and digestive system chapters were the most prevalent, and decreases of 27 and 19 per cent respectively were noted (P < 0.001). Chapters that had the greatest decrease were eye and adnexa (–40.5 per cent; P = 0.002) and respiratory system (–40.7 per cent; P < 0.001), whereas the least affected were neoplasms and pregnancy (8.5 and 7.5 per cent decrease respectively; P = 0.032 and 0.014).

Table 2.

Surgical emergencies classified by chapter and category

| Chapter | Block code | Block label | Control group (2019) | Lockdown group (2020) |

Difference

(%) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infectious diseases | A30–A49 | Other bacterial diseases | 111 (0.15) | 72 (0.13) | –35.14 | 0.014 |

| Total | 111 (0.15) | 72 (0.13) | –35.14 | 0.016 | ||

| Neoplasms | C15–C26 | Malignant neoplasms, digestive organs | 671 (0.92) | 641 (1.11) | –4.47 | 0.433 |

| C50–C58 | Malignant neoplasms, breast and female genital organs | 65 (0.09) | 42 (0.07) | –35.38 | 0.040 | |

| C60–C63 | Malignant neoplasms of male genital organs | 38 (0.05) | 42 (0.07) | 10.53 | 0.687 | |

| C64–C68 | Malignant neoplasms, urinary organs | 276 (0.38) | 263 (0.46) | –4.71 | 0.581 | |

| C69–C72 | Malignant neoplasms, eye, brain, and central nervous system | 47 (0.06) | 34 (0.06) | –27.66 | 0.206 | |

| C76–C80 | Malignant neoplasms, secondary and ill defined | 217 (0.3) | 186 (0.32) | –14.29 | 0.087 | |

| C81–C96 | Malignant neoplasms, stated or presumed to be primary, of lymphoid, haematopoietic, and related tissue | 47 (0.06) | 42 (0.07) | –10.64 | 0.521 | |

| D10–D36 | Benign neoplasms | 99 (0.14) | 85 (0.15) | –14.14 | 0.395 | |

| Total | 1460 (2) | 1335 (2.32) | –8.56 | 0.032 | ||

| Nervous system | G00–G09 | Inflammatory diseases of the central nervous system | 25 (0.03) | 18 (0.03) | –28 | 0.404 |

| G50–G59 | Nerve, nerve root, and plexus disorders | 76 (0.1) | 49 (0.09) | –35.53 | 0.011 | |

| G90–G99 | Other disorders of the nervous system | 25 (0.03) | 9 (0.02) | –64 | 0.017 | |

| Total | 126 (0.17) | 76 (0.13) | –39.68 | 0.003 | ||

| Eye and adnexa | H15–H19 | Disorders of sclera and cornea | 134 (0.18) | 57 (0.1) | –57.46 | 0.083 |

| H25–H28 | Disorders of lens | 26 (0.04) | 0 (0) | –100 | <0.001 | |

| H30–H36 | Disorders of choroid and retina | 165 (0.23) | 147 (0.26) | –10.91 | 0.536 | |

| H43–H45 | Disorders of vitreous body and globe | 70 (0.1) | 31 (0.05) | –55.71 | 0.031 | |

| Total | 395 (0.54) | 235 (0.41) | –40.51 | 0.002 | ||

| Circulatory system | I20–I25 | Ischaemic heart diseases | 285 (0.39) | 187 (0.32) | –34.39 | <0.001 |

| I30–I52 | Other forms of heart disease | 1841 (2.53) | 1480 (2.57) | –19.61 | <0.001 | |

| I60–I69 | Cerebrovascular diseases | 322 (0.44) | 264 (0.46) | –18.01 | 0.031 | |

| I70–I79 | Diseases of arteries, arterioles, and capillaries | 1011 (1.39) | 897 (1.56) | –11.28 | 0.051 | |

| Total | 3459 (4.75) | 2828 (4.91) | –18.24 | <0.001 | ||

| Respiratory system | J30–J39 | Other diseases of upper respiratory tract | 304 (0.42) | 151 (0.26) | –50.33 | <0.001 |

| J85–J86 | Suppurative and necrotic conditions of lower respiratory tract | 24 (0.03) | 17 (0.03) | –29.17 | 0.26 | |

| J90–J94 | Other diseases of pleura | 185 (0.25) | 136 (0.24) | –26.49 | 0.005 | |

| Total | 513 (0.7) | 304 (0.53) | –40.74 | <0.001 | ||

| Digestive system | K00–K14 | Diseases of oral cavity, salivary glands, and jaws | 278 (0.38) | 165 (0.29) | –40.65 | 0.004 |

| K20–K31 | Diseases of oesophagus, stomach, and duodenum | 179 (0.25) | 157 (0.27) | –12.29 | 0.204 | |

| K35–K38 | Diseases of appendix | 5520 (7.58) | 4357 (7.57) | –21.07 | <0.001 | |

| K40–K46 | Hernia | 1614 (2.22) | 1209 (2.1) | –25.09 | <0.001 | |

| K55–K63 | Other diseases of intestines | 3528 (4.84) | 2789 (4.84) | –20.95 | <0.001 | |

| K65–K67 | Diseases of peritoneum | 494 (0.68) | 343 (0.6) | –30.57 | <0.001 | |

| K80–K87 | Disorders of gallbladder, biliary tract, and pancreas | 3292 (4.52) | 3107 (5.4) | –5.62 | 0.089 | |

| K90–K93 | Other diseases of the digestive system | 75 (0.1) | 46 (0.08) | –38.67 | 0.016 | |

| Total | 14 980 (20.57) | 12 173 (21.14) | –18.74 | <0.001 | ||

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue | L00–L08 | Infections of the skin and subcutaneous tissue | 2557 (3.51) | 1773 (3.08) | –30.66 | <0.001 |

| L60–L75 | Disorders of skin appendages | 137 (0.19) | 104 (0.18) | –24.09 | 0.04 | |

| L80–L99 | Other disorders of the skin and subcutaneous tissue | 123 (0.17) | 96 (0.17) | –21.95 | 0.13 | |

| Total | 2817 (3.87) | 1973 (3.43) | –29.96 | <0.001 | ||

| Musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | M00–M03 | Infectious arthropathies | 638 (0.88) | 483 (0.84) | –24.29 | <0.001 |

| M15–M19 | Arthrosis | 37 (0.05) | 12 (0.02) | –67.57 | 0.004 | |

| M20–M25 | Other joint disorders | 29 (0.04) | 6 (0.01) | –79.31 | <0.001 | |

| M45–M49 | Spondylopathies | 46 (0.06) | 47 (0.08) | 2.17 | 0.942 | |

| M50–M54 | Other dorsopathies | 224 (0.31) | 226 (0.39) | 0.89 | 0.941 | |

| M65–M68 | Disorders of synovium and tendon | 600 (0.82) | 475 (0.82) | –20.83 | 0.007 | |

| M70–M79 | Other soft tissue disorders | 371 (0.51) | 348 (0.6) | –6.2 | 0.469 | |

| M80–M85 | Disorders of bone density and structure | 126 (0.17) | 82 (0.14) | –34.92 | <0.001 | |

| M86–M90 | Other osteopathies | 437 (0.6) | 282 (0.49) | –35.47 | <0.001 | |

| M95–M99 | Other disorders of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | 558 (0.77) | 454 (0.79) | –18.64 | 0.012 | |

| Total | 3066 (4.21) | 2415 (4.19) | –21.23 | <0.001 | ||

| Genitourinary system | N00–N08 | Glomerular diseases | 24 (0.03) | 14 (0.02) | –41.67 | 0.096 |

| N10–N16 | Renal tubulointerstitial diseases | 1801 (2.47) | 1714 (2.98) | –4.83 | 0.284 | |

| N17–N19 | Renal failure | 159 (0.22) | 139 (0.24) | –12.58 | 0.265 | |

| N20–N23 | Urolithiasis | 2572 (3.53) | 2590 (4.5) | 0.7 | 0.860 | |

| N25–N29 | Other disorders of kidney and ureter | 27 (0.04) | 32 (0.06) | 18.52 | 0.442 | |

| N30–N39 | Other diseases of urinary system | 90 (0.12) | 56 (0.1) | –37.78 | 0.012 | |

| N40–N51 | Diseases of male genital organs | 642 (0.88) | 446 (0.77) | –30.53 | <0.001 | |

| N60–N64 | Disorders of breast | 24 (0.03) | 21 (0.04) | –12.5 | 0.655 | |

| N70–N77 | Inflammatory diseases of female pelvic organs | 720 (0.99) | 539 (0.94) | –25.14 | <0.001 | |

| N80–N98 | Non-inflammatory disorders of female genital tract | 408 (0.56) | 293 (0.51) | –28.19 | <0.001 | |

| Total | 6467 (8.88) | 5844 (10.15) | –9.63 | <0.001 | ||

| Pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium | O00–O08 | Pregnancy with abortive outcome | 2161 (2.97) | 1925 (3.34) | –10.92 | 0.026 |

| O10–O16 | Oedema, proteinuria and hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium | 238 (0.33) | 247 (0.43) | 3.78 | 0.748 | |

| O20–O29 | Other maternal disorders predominantly related to pregnancy | 51 (0.07) | 45 (0.08) | –11.76 | 0.565 | |

| O30–O48 | Maternal care related to the fetus and amniotic cavity, and possible delivery problems | 1841 (2.53) | 1701 (2.95) | –7.6 | 0.123 | |

| O60–O75 | Complications of labour and delivery | 3118 (4.28) | 2987 (5.19) | –4.2 | 0.331 | |

| O80–O84 | Delivery | 71 (0.1) | 15 (0.03) | –78.87 | 0.3 | |

| O95–O99 | Other obstetric conditions, not elsewhere classified | 31 (0.04) | 27 (0.05) | –12.9 | 0.684 | |

| Total | 7511 (10.31) | 6947 (12.06) | –7.51 | 0.014 | ||

| Others symptoms and diseases | R00–R09 | Circulatory and respiratory systems | 98 (0.13) | 77 (0.13) | –21.43 | 0.253 |

| R10–R19 | Digestive system and abdomen | 35 (0.05) | 18 (0.03) | –48.57 | 0.024 | |

| R30–R39 | Urinary system | 202 (0.28) | 162 (0.28) | –19.8 | 0.025 | |

| R50–R69 | General symptoms and signs | 144 (0.2) | 112 (0.19) | –22.22 | 0.049 | |

| Total | 479 (0.66) | 369 (0.64) | –22.96 | 0.001 | ||

| Injuries | S00–S09 | Injuries to the head | 794 (1.09) | 493 (0.86) | –37.91 | <0.001 |

| S10–S19 | Injuries to the neck | 46 (0.06) | 22 (0.04) | –52.17 | 0.005 | |

| S20–S29 | Injuries to the thorax | 185 (0.25) | 111 (0.19) | –40 | 0.019 | |

| S30–S39 | Injuries to the abdomen, lower back, lumbar spine, and pelvis | 684 (0.94) | 366 (0.64) | –46.49 | <0.001 | |

| S40–S49 | Injuries to the shoulder and upper arm | 2080 (2.86) | 1411 (2.45) | –32.16 | <0.001 | |

| S50–S59 | Injuries to the elbow and forearm | 4264 (5.85) | 3016 (5.24) | –29.27 | <0.001 | |

| S60–S69 | Injuries to the wrist and hand | 5049 (6.93) | 4329 (7.52) | –14.26 | 0.002 | |

| S70–S79 | Injuries to the hip and thigh | 11695 (16.06) | 9269 (16.1) | –20.74 | <0.001 | |

| S80–S89 | Injuries to the knee and lower leg | 5506 (7.56) | 3096 (5.38) | –43.77 | <0.001 | |

| S90–S99 | Injuries to the ankle and foot | 353 (0.48) | 277 (0.48) | –21.53 | 0.005 | |

| T79 | Certain early complications of trauma | 27 (0.04) | 19 (0.03) | –29.63 | 0.133 | |

| T80–T88 | Complications of surgical and medical care, not elsewhere classified | 551 (0.76) | 368 (0.64) | –33.21 | <0.001 | |

| Total | 31 234 (42.88) | 22777 (39.55) | –27.08 | <0.001 | ||

| Other reasons for admission | Z80–Z99 | Persons with potential health hazards related to family and personal history, and certain conditions influencing health status | 222 (0.3) | 241 (0.42) | 8.56 | 0.592 |

| Total | 222 (0.3) | 241 (0.42) | 8.56 | 0.762 |

Values in parentheses are percentages.

Diseases were classified in 78 blocks of categories. Among these, admissions decreased in 71 categories (91 per cent) and increased in seven (9.0 per cent), although these increases were not significant compared with 2019. Among the most common categories requiring emergency surgery, the greatest reduction was observed for injuries to the knee and lower leg (–43.8 per cent; P < 0.001) and injuries to the shoulder and upper arm (–32.2 per cent; P < 0.001). An important reduction for diseases of appendix was also observed (–21.0 per cent; P < 0.001), and admissions related to disorders of gallbladder, biliary tract, and pancreas decreased by 5.6 per cent, although this was not significantly different from 2019 (P = 0.089). Urolithiasis had a moderate increase (0.7 per cent), but the rate was not significantly different from that in 2019 (P = 0.860).

Subcategories occurring in at least 400 admissions are reported in Table 3, and the complete list is available in Table S1. The number of operations for fractures, notably fracture of head and neck of femur (–20.5 per cent), pertrochanteric fracture (–16.8 per cent), fracture of lower leg, including ankle (irrespective of location: –56.0 per cent for upper end of tibia, –53.0 per cent for shaft of tibia, –41.4 per cent for lateral malleolus, –38.5 per cent for other fractures of lower leg) as well as fracture of shoulder and upper arm (upper end of humerus –28.7 per cent, shaft of humerus–36.5 per cent) all decreased significantly compared with 2019.

Table 3.

Surgical emergencies classified by subcategory (selection of most common)

| Chapter | Subcategory code | Subcategory label | Control group (2019) | Lockdown group (2020) | Difference (%) |

P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circulatory system | I442 | Atrioventricular block, complete | 750 (1.03) | 589 (1.02) | –21.47 | 0.002 |

| I743 | Embolism and thrombosis of arteries of the lower extremities | 450 (0.62) | 459 (0.8) | 2 | 0.826 | |

| Digestive system | K352 | Acute appendicitis with generalized peritonitis | 607 (0.83) | 531 (0.92) | –12.52 | 0.184 |

| K353 | Acute appendicitis with localized peritonitis | 1945 (2.67) | 1588 (2.76) | –18.35 | 0.002 | |

| K358 | Other and unspecified acute appendicitis | 2843 (3.9) | 2160 (3.75) | –24.02 | 0.003 | |

| K565 | Intestinal adhesions (bands) with obstruction (after infection) | 884 (1.21) | 721 (1.25) | –18.44 | 0.008 | |

| K566 | Other and unspecified intestinal obstruction | 460 (0.63) | 394 (0.68) | –14.35 | 0.152 | |

| K610 | Anal abscess | 905 (1.24) | 679 (1.18) | –24.97 | 0.004 | |

| K800 | Calculus of gallbladder with acute cholecystitis | 1507 (2.07) | 1411 (2.45) | –6.37 | 0.67 | |

| K801 | Calculus of gallbladder with other cholecystitis | 497 (0.68) | 433 (0.75) | –12.88 | 0.159 | |

| K810 | Acute cholecystitis | 557 (0.76) | 526 (0.91) | –5.57 | 0.231 | |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue | L022 | Cutaneous abscess, furuncle, and carbuncle of trunk | 456 (0.63) | 317 (0.55) | –30.48 | 0.013 |

| L024 | Cutaneous abscess, furuncle, and carbuncle of limb | 589 (0.81) | 381 (0.66) | –35.31 | <0.001 | |

| L050 | Pilonidal cyst and sinus with abscess | 744 (1.02) | 583 (1.01) | –21.64 | 0.003 | |

| Musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | M650 | Abscess of tendon sheath | 434 (0.6) | 319 (0.55) | –26.5 | 0.008 |

| M966 | Fracture of bone following insertion of orthopaedic implant, joint prosthesis, or bone plate | 558 (0.77) | 454 (0.79) | –18.64 | 0.078 | |

| Genitourinary system | N132 | Hydronephrosis with renal and ureteral calculous obstruction | 584 (0.8) | 589 (1.02) | 0.86 | 0.9 |

| N136 | Pyonephrosis | 442 (0.61) | 414 (0.72) | –6.33 | 0.326 | |

| N201 | Calculus of ureter | 1698 (2.33) | 1806 (3.14) | 6.36 | 0.393 | |

| Pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium | O001 | Tubal pregnancy | 602 (0.83) | 516 (0.9) | –14.29 | 0.09 |

| O342 | Maternal care owing to uterine scar from previous surgery | 765 (1.05) | 764 (1.33) | –0.13 | 0.887 | |

| O630 | Prolonged first stage (of labour) | 410 (0.56) | 378 (0.66) | –7.8 | 0.716 | |

| O680 | Labour and delivery complicated by fetal heart rate anomaly | 1179 (1.62) | 1173 (2.04) | –0.51 | 0.879 | |

| Injuries | S422 | Fracture of upper end of humerus | 1095 (1.5) | 781 (1.36) | –28.68 | <0.001 |

| S423 | Fracture of shaft of humerus | 551 (0.76) | 350 (0.61) | –36.48 | 0.009 | |

| S520 | Fracture of upper end of ulna | 431 (0.59) | 275 (0.48) | –36.19 | <0.001 | |

| S525 | Fracture of lower end of radius | 2720 (3.73) | 2061 (3.58) | –24.23 | <0.001 | |

| S526 | Fracture of lower end of ulna | 496 (0.68) | 335 (0.58) | –32.46 | 0.002 | |

| S626 | Fracture of other and unspecified finger(s) | 506 (0.69) | 331 (0.57) | –34.58 | 0.002 | |

| S644 | Injury of digital nerve of other and unspecified finger | 484 (0.66) | 472 (0.82) | –2.48 | 0.64 | |

| S663 | Injury of extensor muscle, fascia, and tendon of other and unspecified finger at wrist and hand level | 980 (1.35) | 917 (1.59) | –6.43 | 0.096 | |

| S720 | Fracture of head and neck of femur | 6020 (8.26) | 4785 (8.31) | –20.51 | <0.001 | |

| S721 | Pertrochanteric fracture | 3685 (5.06) | 3066 (5.32) | –16.8 | 0.029 | |

| S722 | Subtrochanteric fracture of femur | 527 (0.72) | 403 (0.7) | –23.53 | 0.118 | |

| S723 | Fracture of shaft of femur | 681 (0.93) | 454 (0.79) | –33.33 | <0.001 | |

| S821 | Fracture of upper end of tibia | 704 (0.97) | 310 (0.54) | –55.97 | 0.001 | |

| S822 | Fracture of shaft of tibia | 745 (1.02) | 350 (0.61) | –53.02 | <0.001 | |

| S823 | Fracture of lower end of tibia | 450 (0.62) | 286 (0.5) | –36.44 | <0.001 | |

| S826 | Fracture of lateral malleolus | 541 (0.74) | 319 (0.55) | –41.04 | <0.001 | |

| S828 | Other fractures of lower leg | 1750 (2.4) | 1084 (1.88) | –38.06 | 0.001 |

Values in parentheses are percentages.

Mortality

Some 2433 deaths (1.87 per cent) were identified in the original population and 2129 (1.87 per cent) in the matched population (Table S2). After matching, the overall mortality rate was 1.92 per cent (1096 of 56 982) during the lockdown period and 1.81 per cent (1033 of 56 982) in 2019. The adjusted OR for death in the matched population was 1.06 (95 per cent c.i. 0.97 to 1.15). A significant increase in mortality rate was seen in high-prevalence zones (OR 1.22, 1.06 to 1.40); there were no changes in the low- and intermediate-prevalence zones (Table 4).

Table 4.

Mortality by zone of prevalence of COVID-19 infection

| Prevalence zone |

Deaths* |

Odds ratio† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control period | Lockdown period | |||

| High | 374 (1.66) | 417 (2.02) | 1.22 (1.06, 1.40) | |

| Intermediate | 283 (2.01) | 303 (2.05) | 1.02 (0.87, 1.20) | |

| Low | 376 (1.85) | 376 (1.75) | 0.94 (0.81, 1.09) | |

| Total | 1033 (1.81) | 1096 (1.92) | 1.06 (0.97, 1.15) | |

Values in parentheses are

*percentages and

†95 per cent confidence intervals.

Patients with COVID-19

In the subgroup of 863 patients with a diagnosis of COVID-19 infection, the overall mortality rate was 4.0 per cent among those with asymptomatic infection (OR 1.21, 95 per cent c.i. 0.44 to 2.80) and 12.3 per cent for those with symptomatic infection (OR 4.00, 2.60 to 6.32).

Discussion

This study reports a major decrease in emergency procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown period in France. The comprehensive data have permitted an in-depth analysis at a national level. There was a 20.9 per cent reduction in emergency surgical admissions to hospital between the 2020 lockdown and the corresponding interval in 2019. Over the weeks after the end of lockdown, no significant difference was observed between the two periods, suggesting a progressive return to usual surgical practices. The decrease in hospital admissions was associated with the regional prevalence of COVID-19, with the greatest reduction seen in the zones of highest prevalence. As no difference was observed between low- and intermediate-COVID-19 prevalence regions, two levels of impact on emergency surgeries were evident: a major impact in high-prevalence regions and a significantly lower level for all other regions. After matching on all available data, in-hospital mortality was slightly and significantly greater in the lockdown group than in the control group in high-prevalence zones. Additionally, the curve for the number of urgent operations week by week during the lockdown was a mirror image of the curve for number of hospital admissions for COVID-198, suggesting that the availability of hospital beds and operating rooms, requisitioned at the peak of the epidemic, had an impact on the operating capacities of the hospitals.

These findings seem to confirm other experiences reported in the media in the early lockdown periods regarding the dramatic and unexpected reduction in non-COVID emergencies9,10.

The present data are consistent with preliminary reports on acute-care surgery in other countries. In Spain, a 60 per cent decrease in acute surgery activity during the acute phase of the pandemic was reported by three tertiary hospitals in Madrid and Barcelona11. Similarly, an important reduction in traumatic injuries (almost 38 per cent compared with 2019) was observed in a major trauma centre in the UK2. A multicentre study12 from 18 general surgery units in a red zone of COVID-19 contagion reported a 45 per cent decrease in admissions for emergency surgical disease and a 41 per cent decrease in operations, despite no discernible differences in overall management approaches to patients who were admitted during the lockdown.

Several factors have been put forward to explain the reduction in emergency surgery. The most common is the patients’ fear of being taken to hospitals receiving people with COVID-19 and the risk of contracting the virus in that environment. This fear has probably been nourished by worrying information transmitted by the media about the situation in hospitals, such as being overwhelmed by patients with COVID and facing equipment shortages including personal protection, and the lack of reassuring messages from hospitals on the management of patients without COVID. Precise reasons for hospital avoidance remain unclear; only indirect evidence is available. A study13 from the UK reported that people with low-risk conditions were less likely to present to an emergency department whereas the numbers of non-deferrable emergencies remained constant.

There is already some evidence that avoidance of hospital attendance has led to delayed visits to an emergency department, resulting in more advanced disease. The study11 from Spain reported an increased delay of almost 24 h from the onset of symptoms to arrival at a hospital compared with that of a historical control group. A report3 from three medical centres in the state of New York found an increase in paediatric perforated appendicitis compared with uncomplicated appendicitis during the surge of COVID-19 outbreak. Similarly, a number of reports have documented decreases in emergency visits for kidney stone disease, with an increase in severe presentations necessitating admission14,15. These data are consistent with the findings of the present study, where there was a moderate increase (0.7 per cent) in the category urolithiasis (N20–N23).

Lockdown restrictions led to unprecedented modifications in lifestyle, resulting in a reduction in road traffic collisions and consequent trauma. In the UK, road casulaties dicreased of 67 per cent compared with 201916. Associations between acute diseases and other lifestyle changes such as food and alcohol consumption, or physical activity, is less straightforward. During the 8-week lockdown in France, a survey of 3000 adults found that men gained an average of 2.7 kg and women 2.3 kg17. If short-term weight gain influences the risk of cholecystitis, this might provide partly explain why the reduction in acute cholecystitis (K810, decrease of 5.6 per cent) was relatively modest.

Another issue may have been a shift, when possible, from surgical to medical treatment. This has been suggested for uncomplicated appendicitis or cholecystitis18,19. This might also explain why some disorders for which there is no non-surgical alternative, such as incarcerated hernia or bowel perforation, showed a more moderate reduction13. In the absence of evidence of catching up at the end of the lockdown period in the present study, it can be argued that conservative treatment represented a feasible solution for some patients. This warrants further study in relevant conditions.

In many healthcare settings, elective surgery has been severely curtailed. Although this inevitably resulted in fewer complications requiring urgent surgical revision11,20, this must be set against patients listed for elective surgery whose problems deteriorated, leading to an urgent surgical admission. Despite this, the reduction for some conditions remains difficult to explain, in particular for life-threatening diseases such as bowel perforation or incarcerated hernia.

The decrease in admissions for emergencies requiring surgical treatment in the present study was also related to the local prevalence of COVID-19. The analysis highlighted that the decrease in surgical emergencies was identical in zones with a low and intermediate prevalence of COVID-19 infection, and different from that in high-prevalence zones. The mortality rate was also associated with the regional prevalence of hospital admission for COVID-19, with an increased odds of a fatal event. This might suggest that, when a threshold is exceeded in emergency departments, the quality of care may be affected and the mortality rate increases. Previous studies2,11,12 with contradictory findings may have suffered from having relatively small sample sizes.

The present study has limitations. It was based on an administrative database using classification of disease (ICD-10) codes, rather than on clinical data. Although ICD codes can be extremely accurate, they are not always consistent with clinical classification; for instance, there is no correlation between the Hinchey classification for perforated diverticulitis and ICD codes21. The use of a standardized classification does, however, facilitate reproducibility and comparison. Furthermore, admissions were classified only with respect to the main diagnosis, which seemed appropriate for most patients, but could be a simplification for complex emergencies, such as patients with multiple traumatic injuries. No information on conservative treatment in primary or secondary care or medical treatment for surgical emergencies is available. As a result, the decrease in surgical admissions might have overestimated the real incidence of acute surgical conditions. These limitations, however, must be seen in the context of a comprehensive data set at national level which, as a result of using ICD-10 codes, permits comparison with other countries.

The pandemic coupled with a national lockdown had a massive impact on emergency operations, especially in zones with a higher prevalence of COVID-19 infection, where in-hospital mortality increased significantly. Although the surgical community has the ability to adapt and cope with emerging viral infections, such as the human immunodeficiency virus and severe acute respiratory syndrome21, it is essential that health authorities act to preserve an adequate workforce, prevent scarcity of resources, and continue to deliver appropriate messages to the public in order to maintain adequate surgical services.

Disclosure. All authors delcare no conflict of interest concerning the present study.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at BJS Open online.

Supplementary Material

Presented to the Congress of the French Society of Digestive Surgery webinar, November 2020

References

- 1. Mesnier J, Cottin Y, Coste P, Ferrari E, Schiele F, Lemesle G. et al. Hospital admissions for acute myocardial infarction before and after lockdown according to regional prevalence of COVID-19 and patient profile in France: a registry study. Lancet Public Health 2020;5:e536–e542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rajput K, Sud A, Rees M, Rutka O. Epidemiology of trauma presentations to a major trauma centre in the North West of England during the COVID-19 level 4 lockdown. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2020;30:1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fisher JC, Tomita SS, Ginsburg HB, Gordon A, Walker D, Kuenzler KA.. Increase in Pediatric Perforated Appendicitis in the New York City Metropolitan Region at the Epicenter of the COVID-19 Outbreak. Ann Surg 2021;273:410–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cano-Valderrama O, Morales X, Ferrigni CJ, Martín-Antona E, Turrado V, García A. et al. Reduction in emergency surgery activity during COVID-19 pandemic in three Spanish hospitals. Br J Surg 2020;107:e239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bannay A, Chaignot C, Blotière PO, Basson M, Weill A, Ricordeau P. et al. The best use of the Charlson comorbidity index with electronic health care database to predict mortality. Med Care 2016;54:188–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. WHO. ICD-10 Version:2010http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2010/en (accessed 17 October 2020)

- 7. Austin PC, Stuart EA.. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med 2015;34:3661–3679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Santé publique France. COVID-19 : chiffres clés et évolution. https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/dossiers/coronavirus-covid-19/coronavirus-chiffres-cles-et-evolution-de-la-covid-19-en-france-et-dans-le-monde (accessed 17 October 2020)

- 9. Le Monde. Journal de crise des blouses blanches : « Mais où sont passées les autres urgences ? ». https://www.lemonde.fr/journal-blouses-blanches/article/2020/03/31/journal-de-crise-des-blouses-blanches-mais-ou-sont-passees-les-autres-urgences_6035081_6033712.html (accessed 17 October 2020)

- 10. Feuer W. Doctors Worry the Coronavirus Is Keeping Patients Away From US Hospitals as ER Visits Drop: ‘Heart Attacks Don’t Stop’. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/04/14/doctors-worry-the-coronavirus-is-keeping-patients-away-from-us-hospitals-as-er-visits-drop-heart-attacks-dont-stop.html (accessed 18 October 2020)

- 11. Cano-Valderrama O, Morales X, Ferrigni CJ, Martín-Antona E, Turrado V, García A. et al. Acute care surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: changes in volume, causes and complications. A multicentre retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg 2020;80:157–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rausei S, Ferrara F, Zurleni T, Frattini F, Chiara O, Pietrabissa A. et al. Dramatic decrease of surgical emergencies during COVID-19 outbreak. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2020;89:1085–1091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McLean RC, Young J, Musbahi A, Lee JX, Hidayat H, Abdalla N. et al. A single-centre observational cohort study to evaluate volume and severity of emergency general surgery admissions during the COVID-19 pandemic: Is there a “lockdown” effect?. International Journal of Surgery 2020;83:259–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Antonucci M, Recupero SM, Marzio V, De Dominicis M, Pinto F, Foschi N. et al. The impact of COVID-19 outbreak on urolithiasis emergency department admissions, hospitalizations and clinical management in central Italy: a multicentric analysis. Actas Urol Esp 2020;44:611–616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tefik T, Guven S, Villa L, Gokce MI, Kallidonis P, Petkova K. et al. Urolithiasis practice patterns following the COVID-19 pandemic: overview from the EULIS Collaborative Research Working Group. Eur Urol 2020;78:e21–e24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Department of Transport. Reported road casualties in Great Britain: provisional estimates year ending June 2020. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/reported-road-casualties-in-great-britain-provisional-estimates-year-ending-june-2020 (accessed 1 February 2021)

- 17. Darwin Nutrition. Sondage IFOP pour Darwin Nutrition: l’impact du confinement sur l’alimentation des Français.es. https://www.darwin-nutrition.fr/actualites/alimentation-francais/ (accessed 17 October 2020)

- 18. Collard M, Lakkis Z, Loriau J, Mege D, Sabbagh C, Lefevre JH. et al. Antibiotics alone as an alternative to appendectomy for uncomplicated acute appendicitis in adults: Changes in treatment modalities related to the COVID-19 health crisis. J Visc Surg 2020;157:S33–S42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. American College of Surgeons. COVID-19 Guidelines for Triage of Emergency General Surgery Patients. https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/elective-case/emergency-surgery (accessed 17 October 2020)

- 20. Collard MK, Lefèvre JH, Batteux F, Parc Y, Peschaux F, Wind P. et al. ; APHP/Universities/Inserm COVID‐19 Research Collaboration. COVID-19 heath crisis: less colorectal resections and yet no more peritonitis or bowel obstruction as a collateral effect? Colorectal Dis 2020;22:1229–1230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Martellotto S, Challine A, Peveri V, Paolino L, Lazzati A.. Trends in emergent diverticular disease management: a nationwide cohort study from 2009 to 2018. Tech Coloproctol 2021;25:549–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.