Abstract

Objective: In this systematic review, we aimed to evaluate the existing strategies and interventions in domestic violence prevention to assess their effectiveness.

Method : To select studies, Pubmed, ISI, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Cochrane, Scopus, Embase, Ovid, Science Direct, ProQuest, and Elsevier databases were searched. Two authors reviewed all papers using established inclusion/ exclusion criteria. Finally, 18 articles were selected and met the inclusion criteria for assessment. Following the Cochrane quality assessment tool and AHRQ Standards, the studies were classified for quality rating based on design and performance quality. Two authors separately reviewed the studies and categorized them as good, fair, and poor quality.

Results: Most of the selected papers had fair- or poor-quality rating in terms of methodology quality. Different intervention methods had been used in these studies. Four studies focused on empowering women; 3, 4, and 2 studies were internet-based interventions, financial interventions, and relatively social interventions, respectively. Four interventions were also implemented in specific groups. All authors stated that interventions were effective.

Conclusion: Intervention methods should be fully in line with the characteristics of the participants. Environmental and cultural conditions and the role of the cause of violence are important elements in choosing the type of intervention. Interventions are not superior to each other because of their different applications.

Key Words: Domestic Violence, Intervention Study, Program Effectiveness, Systematic Review, Women

Domestic violence (DV) can be a major health problem (1) and one of the causes of death and disability in women that depends on the local culture where the woman lives (2). Violence against women as a health concern is increasing (3). This issue will increase the demand for health services (4). DV can be physical, sexual, economic, and psychological (5). Scientific evidence suggests that DV causes physical injuries, gastrointestinal disorders, chronic pain syndrome, depression, anxiety, suicidal behaviors, and pregnancy problems, such as unwanted pregnancy, illegal abortion, and preterm labor (6).

Besides, this phenomenon can affect children in the future. Studies show that the risk of behavioral problems and emotional injuries in children who experience violence increases in the future (7).

According to a recent WHO report, 37% of Eastern Mediterranean countries have the highest rate of violence against women (8). Surveys show that the prevalence of violence against women varies from 27% to 83% between different communities, and this diversity may be due to cultural differences (9, 10).

Recent studies in Iran show that about 66% of married women during the first year of their marriage have experienced some form of violence by their current or ex-spouse (9).

Although the problem of DV is very serious, it can be well screened for routine symptoms of DV during general health services (11). The ultimate goal is to stop the violence before it begins. For this purpose, it is important to understand the factors that trigger violence. Studies show that traditional misconceptions, low literacy levels, poor knowledge about women's rights, and lack of social support for abused women can lead to various forms of violence against women (1). Violence tracking is the first step in controlling DV (11). In contrast, any delay in the early detection of this phenomenon can cause serious harm to the well-being of women and children. Based on previous systematic review studies in Iran, various interventions and prevention methods have been used to control DV and overcome this social dilemma.

Despite recent information about the epidemiology of violence based on recent studies, there is still less evidence-based approaches in primary health care services for the prevention and control of DV against women. The assessment of different interventions to improve the well-being of affected women is still a key research priority (12). Thus, there is an urgent need to design complementary research with very robust and comprehensive research methods to evaluate the effectiveness of existing intimate partner violence (IPV) interventions. According to the available documentation, serval interventions have been designed to combat violence against women. Some of these interventions are specific to a particular type of violence. But nowadays, according to the documentation, there is a need for implementation of social support programs and interventions for women, children, and their partners. Also, it seems few randomized control trials (RCT) as a robust design have been performed in this field, and studies have reported that the results of the intervention were effective, but the quality of these studies should be assessed.

Finally, methods should be selected and designed to be effective, simple, accessible, and practicable for different demographic groups and health care settings. According to the mentioned evidence-based facts, in this research project, we aimed to evaluate the existing strategies and interventions in DV prevention, using a systematic review, to assess their effectiveness to choose the best applicable and effective methods.

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy and Study Screening Process

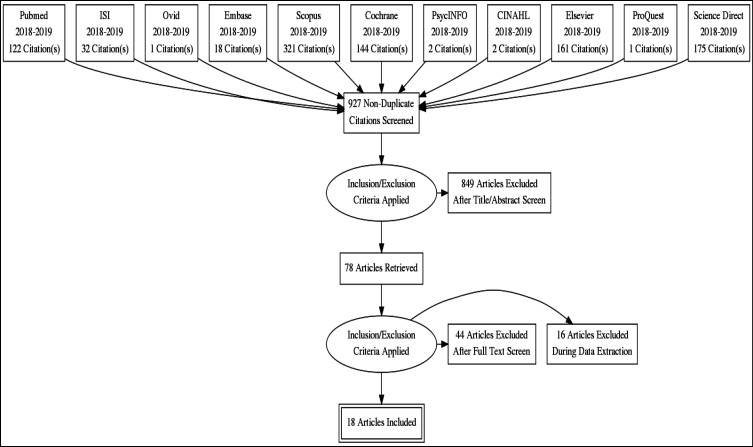

This systematic review was conducted in 2019. To select appropriate studies, an extensive search was conducted. Pubmed, ISI, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Cochrane, Scopus, Embase, Ovid, Science Direct, ProQuest, and Elsevier databases were searched to cover published articles from 2000 to 2019.To select studies, we used the keywords such as Domestic Violence Family, Violence Partner Abuse, Intimate Partner Violence, Abused, and Women. The type of included studies was intervention clinical trial, randomized controlled trial, and prevention trials. Therefore, these terms were used as keywords as well. Also, references of the selected articles were searched manually. Two researchers conducted the resource search process separately and eventually coordinated the selected studies. In the first searching phase, 921 articles were selected. Using manual searching, 58 related articles were found. Finally, 979 articles were selected. Duplicating articles were detected by one researcher and supervised by a subsequent researcher using EndNote (X8) software. The number of articles after this process reached 927. Then, the title and abstract of articles were evaluated based on inclusion criteria. Consequently, 78 articles met the inclusion criteria. By reviewing the full-texts of articles, 44 were excluded due to inappropriate content. Out of the remaining 34 articles, 16 were excluded considering their designs. Finally, 18 eligible studies were reviewed. Finding and Screening Flowchart were plotted using the PRISMA Flow Diagram Tool (13), which is reported in Figure 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We considered all studies with a RCT design, as eligible for inclusion if they examined PICO as a tool (Table1) for developing a search strategy for identifying potentially relevant studies in any topic about DV with prevention approach. We applied other restrictions in this review, such as studies related to the English language and their publication time was from 2000 to 2019. Also, articles whose full texts were not accessible were excluded.

Table1.

Description of PICO Criteria Applied to the Selecting Studies

| Population or Problem | Intervention | Comparison | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Studies with interventional design, which examines the impact of interventions on reducing any type of violence against women | Any type of applied intervention such as women empowerment, economic, social, educational, etc to prevention and reduction of DV |

The comparison could be any desired approach, such as in reach facilitates, routine cares or placebo | Reduction occurrence and repetition of DV and any type of violence such as sexual, emotional, physical, financial, etc, against women |

Quality Evaluation of Selected Articles (Risk of Bias Assessment)

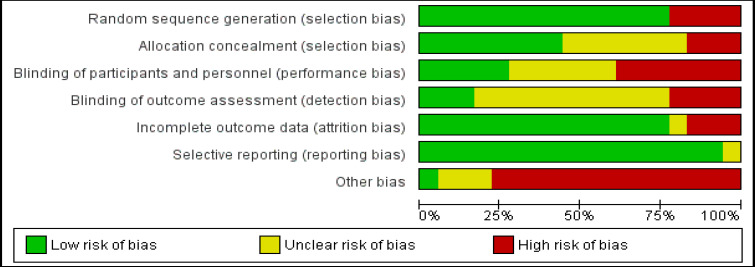

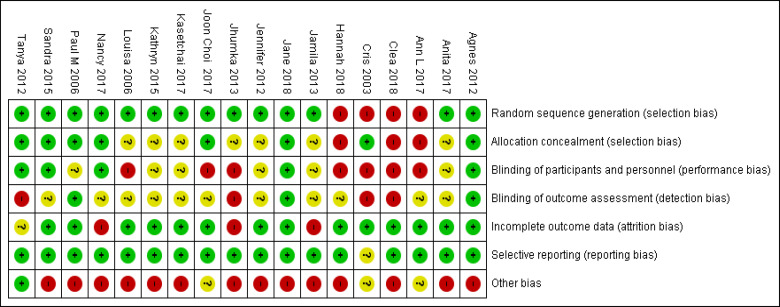

The Cochrane Risk-of-Bias Tool was used for the qualitative evaluation of the articles, considering the design of the papers that had the RCT methods (14). This tool has 7 criteria to assess the quality of articles in terms of bias. Articles were evaluated by 2 researchers using this tool separately. There was a 25% inconsistency between both researchers. To resolve the disagreement, a third-person re-evaluated and judged the disputes. Using the instructions of the Cochrane quality assessment tool, the studies were classified for quality rating, based on design and performance quality according to the AHRQ Standards. Therefore, the studies were categorized into 3 subgroups: good, fair, and poor quality (14). Table 2 illustrates these subgroups. Thereafter, data were entered into Review Manager Software (version: 5.3). The results are presented as the risk of bias graph (Figure 2) and the summary of the risk of bias graph (Figure 3).

Table 2.

Summary of Characteristics Domestic Violence Intervention Studies

| Study Source | Eligibility |

Participants / Study

Groups |

Interventions/ Time

Follow up |

Outcomes

Assessment |

Results |

Quality

Rating |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Women Empowerment

Interventions |

Agnes Tiwari et al(18), 2012 |

18 years or older Women and Positive for IPV |

Women using child care, (100 women per group) |

Empowerment Intervention, and Community Services / 9 months |

Self-reporting | The intervention was efficacious |

Fair |

| Hannah M. Clark et al(19), 2018 |

Spanish speaking women, with experienced IPV the past 2 yr, with child (4-12yr) |

Spanish-speaking Latina mothers Treatment (n=55) Control (n=40) |

Moms’ Empowerment Program (MEP) / 10 weeks |

Interviewing, Self-Reporting | MEP participants reported lower Total IPV, |

Poor | |

| Jhumka Gupta et al(20), 2013 |

Women with 18 years old and over |

Treatment (n=513), control (n=421) |

VSLA & GDG Intervention / 4 months |

Self-report by women and interviewing | Intervention significantly reduced IPV | Poor | |

| Sandra A. et al(21), 2015 |

Women with IPV and with children between the ages of 6 and 12. |

Mother-plus-child (n=61), Child-only (n=62), and Comparison group (n=58) |

A community-based therapeutic group intervention, | Using the Severity of Violence against Women Scales (SVAWS) |

Intervention program was successful in moderate change in IPV | Fair | |

| Interventions for Specific target groups | Ann L. Coker et al(22), 2017 |

There was no specific criterion, schools selected from rape crisis. | 89,707 students, 46 high schools in intervention or control conditions |

The Green Dot violence prevention program / 3 years |

Interviewing, Self-Reporting | Green Dot! was effective | Poor |

| Louisa Gilbert et al(23), 2006 |

Women aged 18 or older, using any illicit drug and IPV affected | intervention (n = 16), control (n=18) | Relapse prevention and relationship safety (RPRS) / 3 months |

IPV measurement using the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales |

RPRS intervention was effective | Poor | |

| Kasetchai Laeheem et al(24), 2017 |

Thai Muslim married couples | 40 Thai Muslim married couples, Experiment (n=20) Control (n=20) | Happy Muslim Family Activities /12 weeks | Pretest & Posttest | Intervention in experimental group was effective |

Poor | |

| Jennifer Langhinrichsen- Rohling et al(25),2012 |

At-risk adolescent females | Intervention (n=39) control (n=33) | Building A Lasting Love (BALL) Program/ 6 weeks | Psychological Aggression Subscale, checklist |

The program had some impact on IPV control | Poor | |

| Jamila Mejdoubi et al(26),2013 |

Disadvantaged women <26 years, with no previous live births |

Pregnant women, control (n=223),intervention (n=237) |

Nurse-Family Partnership (NFP) / 32 weeks |

Self-reporting | Intervention was effective during pregnancy and after birth | Poor | |

| Internet-Based interventions | Jane Koziol- McLain et al(27), 2018 |

English-Speaking women aged 16 years or older |

General population (women) Control(n = 226) Intervention (n=186) |

Web-based safety Decision Aid / 12 months |

Using Checklist & Scales |

Intervention was effective in reducing IPV and depression |

Fair |

| Y. Joon Choi et al(28) , 2017 |

Korean or Korean American, and that either the clergy member |

Korean American faith leaders Intervention (n = 27), control (n = 28) |

Korean Clergy for Healthy Families (KOCH)/3 month |

Self-administrated questioner |

Knowledge and attitudes increased about resources to handle IPV |

Fair | |

| Nancy E. Glass et al(29), 2017 |

Past 6 months abused Spanish- or English-speaking women, |

Currently abused women, intervention (n=418) control (n=423) |

A Tailored Internet-Based Safety Decision Aid / 6-12 months | Internet based self-reporting | Intervention increased safety behaviors and reduced IPV | Poor | |

| Financial Interventions | Paul M Pronyk et al(30), 2006 |

Women, household co-residents aged 14–35 years |

8 villages, Cohort one (860) Cohort two (1835) Cohort three (3881) |

Intervention with Microfinance for AIDS and Gender Equity (IMAGE) / 2-3 yr |

Face-to-face Structured interviews |

IPV violence reduced in the intervention group |

Fair |

| Clea C. Sarnquist et al(31), 2018 |

Adult women IPV survivors,18 years of age or older |

Adult women IPV survivors / intervention (n = 82) control (n = 81) |

Combination of Business Training, Microfinance, and IPV support / 8 weeks |

DHS questions on domestic violence |

Intervention increased daily profit margin and decreased the IPV | Poor | |

| Kathryn L et al(32), 2015 |

Women aged 18 years and older with no previous microfinance experience |

Intervention group (934) partnered women, in 24 villages in rural |

Combined Social and Economic Empowerment Program / 2 year | Self-report by women and interviewing |

Was effective in participants with a history of adult marriage |

Poor | |

| Anita Raj et al(33), 2017 |

Couples aged 18-30 years for the husband and aged 15 + years for the wife |

Rural young married couples (N = 1091) | Women's Economic Empowerment (CHARM) / 9 -18 month |

Self-reporting | Intervention reduced the risk of IPV among married women |

Poor | |

| Other Interventions | Tanya Abramsky et al(34), 2012 |

Being at risk to domestic violence, men and women aged 18 to 49 years |

Eight sites, control and intervention groups (800 men, 800 women) |

SASA! Intervention (Gender Focused Intervention),4 Years |

Interviewing | Positive impact on reduction of domestic violence | Fair |

| Cris M. Sullivan et al(35), 2003 | Women recruited from domestic violence shelter program |

Intervention (n=143) control (n=131) |

Experimental Social Innovation and Dissemination (ESID) model / 6-24-month |

Face-to-face structured interviews |

Women in intervention group significantly less abused again | Poor |

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flowchart Screening and Selection of Studies

Figure 2.

Assessment of Methodological Quality of Selected Studies (Risk of Bias Graph)

Figure 3.

Assessment of Methodological Quality of Selected Studies (Risk of Bias Summery)

Results

As noted, after a comprehensive search and qualitative evaluation of studies, finally 18 articles were selected for evaluatation. Based on the included articles, to prevent and control the violence against women in different countries, different models have been applied to various groups. In included articles, DV against women has been considered physical, emotional, sexual, financial, etc, by the wife or partner of the woman. The results of the studies show various screening tools for violence. For example, some of these tools were used in primary health care (15), some for pregnant women (16), and some for men (17). Of the final selected papers, the oldest was in 2003 and the newest in 2018. All final selected articles had an RCT design. Based on selecting the population to perform the interventions, there were various target groups and intervention methods. Most studies focused on empowering women. In 3 studies, the internet sites had been applied to conduct interventions. Four studies had also evaluated economic interventions and financially empowerment methods in couples. Two studies had used kinds of social intervention. Follow-up times were different between studies, and in some studies, the follow-up period was 4 years. In all selected studies based on the study goal, a preventive intervention method was considered for the study target group. The control group consisted of those who either did not receive any intervention or received another intervention to compare the efficacy of the method applied to the intervention group or were under routine care and treatment. Also, it was found that to assess the effectiveness of interventional methods, the amount of inflicted violence on women was either self-reported or measured using standard measurement tools. Evaluation of the design and quality of these studies based on the relevant evaluation checklists indicated that all studies had strengths and weaknesses in the method of implementation and process of the research. Most of the papers were at the fair or poor-quality level in terms of methodology quality rating. The summary of the characteristics of reviewed studies in this project that met the inclusion criteria was reported in Table 2.

Summary of Included Studies

Women Empowerment Interventions

In 4 included studies in this systematic review, women empowerment interventions were used to combat DV. The first study in this field was done in 2012 in china (18). Women aged 18 years or older with a positive screening for DV (n = 200) and small children were recruited to participate. The intervention was a community-based advocacy program, consisting of 2 components: empowerment and telephone social support. The intervention aimed to increase abused women’s safety and enhance their problem-solving ability. After the intervention, in the treatment group, the mean of safety behavior was increased almost a 5-fold significantly. The other study by Hannah in 2018, reported the reducing IPV in Spanish-Latinas speaking women (19). Inclusion criteria were having a history of IPV in the past 2 years and having a child of 4 to 12 years. The intervention was a community-based Moms’ Empowerment Program (MEP). MEP was used as an interpersonal relationship to empower women to increase women’s self-efficacy and reduce their self-blame. Although the sample size was not significant (intervention group = 55, control group = 40), the intervention (36) was significantly effective in the treatment group, especially physical violence. Because of the selection of specific groups of participants, the generalizability of the results was controversial. In a study by Jhumka Gupta, women over 18 years with at least 1-year marriage duration were involved (20). The intervention in this study was relatively different from the 2 previous studies. The control arm (n = 421) received VSLA (village savings and loan associations) and the treatment arm (n = 513) received VSLA and an 8-session gender dialogue group (GDG). The GDGs were developed between men and women to address household gender inequities and communication. Despite some methodological limitations, the results of this study were also effective in the VSLA-GDG group, but it was not significant. Another community-based intervention to empower women was in 2015 by Sandra (21). The intervention was a 10 session community- based therapeutic group program. The study included women who had a physical conflict and their children aged 6 and 12 years. Participants were categorized into 3 groups: mother-plus-child (n = 61), child-only (n = 62), and comparison group (n = 58). The intervention focused on enhancing women's skills, strengthening them in connecting to social support, and also empowering children to improve children's attitudes about DV to manage this health problem. This intervention with good methodological status like previously (37) had a moderate change in IPV prevention.

Interventions for Specific Groups

Out of 18 selected articles, in 5 the interventions were applied to specific groups. The applied interventions were also specific. In one study, the name of the intervention was the Green Dot program (22). In this method, male and female students (n = 89 707) were involved and received training about the types of violence (most sexual violence). These students had to train their friends as leaders. Although the study had a methodological limitation, at the end of the study, the different types of violence (especially sexual violence) and alcohol or drug-facilitated sex in schools reduced significantly. In the next study by Louisa Gilbert, drug user women were target groups (23). The aim was to assess the impact of RPRS (Relapse Prevention and Relationship Safety) to reduce IPV and prevent drug use in addicted women. According to experts, RPRS is suitable for women who experience different levels of violence and have multiple partners. The RPRS enables participants to avoid IPV and drug use by behavior changes and training suitable negotiation methods. After the intervention, in the RPRS group, about 5.3 times reduction in physical and sexual violence and 6 times in psychological violence was obtained. Another interesting study was applying religious methods (Happy Muslim Family Activities) to reduce DV. The study was conducted by Kasetchai Laeheem in 2017(24). In this study, certain religious norms and practices have been used as an intervention in Thailand's Muslim population to control violence against women. This method used Islamic methods and teachings to change the behavior of the couples, improve their attitude, and reinforce their morality. Despite the limitations, violence in this study was also reduced significantly in the intervention group. In the fourth study, Jennifer et al in 2012 examined the effect of BALL intervention (Building A Lasting Love Intervention) to reduce violence on young African American pregnant girls (n = 72)(25). This program focused on the signs of healthy versus unhealthy romantic relationships, personal relationship skill, and problem-solving techniques. Findings indicated that the program had some impact on IPV reduction in the treatment arm. In the last study, Jamila Mejdoubi evaluated the effect of nursing home care intervention to IPV control on 237 pregnant women (26). Women received approximately 50 nurse home visits during pregnancy, first-year, and second-year life of the child by trained nurses. During each home visit, the health status of the mother and child, mitigation of risk factors for IPV, and informing about consequences of IPV were intended. At the end of the study, about 50% reduction in violence (sexual, physical, and psychological) was obtained in the intervention group.

Internet Based Interventions

In 3 included studies, the internet-based interventions were applied. In the study of Jane Koziol-McLain conducted on 186 women aged 16 years and over, the study aimed to test the efficacy of a web-based safety decision aid to reduce IPV exposure by improving women's mental health (27). Participants were followed up for 1 year, and the study discovered that intervention was effective in reducing violence and depression symptoms. The next study in 2017 by Nancy E. Glass was conducted using the same methodology and yielded similar results (29). Other online intervention (KOCH) in 2017 by Joon Choi was designed to examine the impact of a short intervention for preventing and addressing IPV (28). About 55 Korean-American religious leaders were included in the study. The KOCH aimed to increase self-efficacy, knowledge of IPV, and improve attitudes that support IPV. After the 3-month follow-up, findings indicated that the intervention was effective and knowledge of clergy and their attitudes against IPV increased significantly.

Financial Interventions

Four studies have used financial interventions to reduce IPV. The first intervention (IMAGE) by Paul M Pronyk in 2005 aimed to assess a structural intervention on women aged 14-35 years in 8 matched villages (30). There were 3 groups: women who applied for loans (n = 843), women who were also living with loans applied women (n = 1455), and randomly selected women from that area (n = 2858). The intervention consisted of income-generating activities, gender roles, cultural beliefs, relationships, and IPV facts training curriculum. At the end of the study, the experience of IPV either physical or sexual reduced by 55%, and household economic wellbeing along social capital increased. The small number of clusters, short duration of follow-up, and biased reporting were several limitations of the study. The next intervention (Mashinani) by Clea Sarnquist was a woman empowering program through a combination of formal business training, microfinance, and IPV reduction activities (31). Women aged 18 years or older who were victims of DV were included. Women received their first loan and began their business activities according to their job plan. After 4 to 5 months of follow-up, the results showed that interventions affected increasing daily profits and decreasing DV. Another study by Kathryn L in 2015 was slightly different in terms of intervention and subjects (32). Researchers hypothesized that interventions on reducing IPV and economic abuse are not more effective on women married as child brides (<17 years). Women aged 18 years and older with no previous microfinance experience were eligible. The intervention aimed at the reduction of IPV and economic abuse using gender equality promotion activities. After the intervention, most forms of IPV were lower among women married as adults, and the study showed that interventions were less effective in women who are married at an early age. The last study by Anita Raja (CHARM intervention) in 2017 has particularly focused on women's economic empowerment (33). This research involved longitudinal examinations of women's financial independence and its associations with consequent incident IPV. The intervention was economic programs and gender equity training sessions. Eligible couples were women over 15 years with husbands aged 18-30 years. Finally, findings indicated that women's economic conflict with owning a bank account and involvement of married women with their husbands in business can reduce the occurrence and recurrence of IPV.

Other Interventions

Intervention in 2 studies was nearly social. The first study (SASA) by Tanya Abramsky in 2012 emphasized prevention violence and HIV/AIDS in women in African countries (34). SASA intervention used a community mobilization approach by changing the community attitudes, norms, behaviors, and ending of gender inequality and societal misconceptions to prevent violence against women. Participants in the study were men and women aged 18 to 49 years. After 4 years, in the intervention group, attitudes improved toward violence, and social support responses to helping affected women increased. The ESID intervention was another social method by Cris M. Sullivan in 2003 (35). In this intervention, the role of social professionals by making innovations was crucial. Female undergraduate students were used to conduct the intervention on shelter women after community psychological training. Training courses were about empathy and active listening skills, IPV facts, managing dangerous situations, and accessing community resources. This intervention was also effective, and results indicated that women in the treatment arm were significantly less likely to be abused again, and they also reported a higher quality of life and fewer difficulties in obtaining community resources.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we examined the effectiveness of applied interventions and existing strategies to prevent IPV in 18 selected RCT articles. Reviewing the studies revealed that different interventions and therapeutic methods have been developed to control and reduce violence against women in different regions and countries. Included studies were also reviewed methodologically. Almost all articles received a fair- or poor-quality rating based on the Cochrane quality assessment tool. These limitations in the studies can preclude drawing any conclusions about the effectiveness of interventions.

Reviewing the papers also revealed that the selection of suitable screening tools, determining the amount of inflicted violence, and selecting effective methods to outcome assessment of interventions should be considered widely by researchers. The results of the studies showed that there are various screening tools for violence. For example, some of these tools were used in primary health care (15), some for pregnant women (16), and some for men. Based on included articles, very few studies to date have evaluated the effectiveness of screening programs to reduce violence or to improve women’s health. Also, data about the potential harms associated with these programs are lacking. Selecting the appropriate tool to assess outcomes of interventions is also controversial. Based on evidence, there is no complete consensus that the measurement of the recurrence of violence against individuals can be used as an appropriate tool to assess the effectiveness of interventional methods. Many researchers believe that most women do not have any control on re-violence over themselves (16). Furthermore, some insist on self-reporting by women, and there is great evidence that women underreport the violence and abuse against themselves (15).

In all reviewed articles, all authors stated that interventions were efficient, and there was no article declaring that the intervention was not effective. Likewise, most of the interventions were on women. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution.

Some studies have used the internet to intervene as an innovation. The researchers suggest that the online intervention provides a vehicle for creating awareness and action for change in a private space (27, 38). Based on the evidence, online data collection may help reduce some biases, and online training can eliminate general barriers to participation (39). Although this method may apply to certain groups, many abused women seek information online, and available information typically is not tailored to their circumstances.

Reviewing selected studies revealed that social factors are very efficient in designing and implementing interventions. Considering this, the many goals on IPV prevention programs can be achieved by changing gender inequality behaviors and societal misconceptions. Due to cultural resistance, these changes may be slow. Based on the evidence, one of the causes of disability in women depends on the local culture in which they live (32). According to WHO, one of the most important roles of public health in controlling DV is addressing social and cultural norms related to gender that support IPV (40).

Results of papers also showed that the role of social education and individual skills in enhancing women's social capital and reducing violence is important. Education plays both direct and indirect roles in the prevention of IPV (41). Based on studies, a positive attitude toward male dominance, belief about women as a lower rank in the creation, and many other cultural gender inequities rationalize violence against women (42). Thus, it seems that social scientists should play an active role in creating positive societal change in women with abusive partners who needed access to a variety of community resources.

In several studies, children had participated in the interventions, and the methods were effective likewise. Children as witnesses of parental violence learn that violence is a way to deal with marital problems, and when they grow up, they will commit violence against their own families (43). This matter should be widely considered in future works that children need to understand the facts of violence and learn how to manage it.

There have been some economic empowerment programs that have yielded somewhat conflicting results to reduce IPV and decrease its health harms (44). Studies state that women's revenue formation or their higher-earning than men are associated with increased rather than a reduced chance for IPV (45). Experts emphasize that the financial empowerment of women can reduce the risk for IPV, especially if sponsored with attempting to improve gender equity norms (46). Based on the evidence, when norms do not accept women's employment well, these programs may not be effective in controlling IPV (47).

Religious leaders can be effective in reducing violence against women in some countries. Some studies have emphasized the use of the process of Islamic socialization to prevent IPV. Related specialists believe that promoting Muslims to participate in activities that develop their potential with emphasis on Islamic morality and ethics can prevent and solve the problem of aggressive behavior (48). It is recommended that such interventions be performed for other religions as well.

Appraising included studies also showed that more vulnerable groups, such as students, pregnant and addicted women, should be considered separately and receive appropriate intervention programs to prevent violence. The Nurse-Family Partnership (NFP) (49) and Bystander intervention programs were specifically effective interventions conducted on young high-risk pregnant women and students to reduce the probability of violence respectively (50, 51).

Limitation

In the ongoing systematic review, we had some potential weaknesses. We limited this systematic review to English-language articles with available full-text. These constraints can lead to potential publication bias. Also, the search process restricted to selecting papers with an RCT design, and very effective interventions may have been made with different designs in other languages. Finally, it seems that a scoping review or narrative review be the most appropriate method instead of the systematic review approach for assessing or responding to such a wide study objective. Despite these limitations, we believe that conducting extensive search and selecting a variety of interventional studies in sufficient numbers can be one of the strengths of our study.

Conclusion

Most of the selected papers had fair- or poor-quality rating in terms of methodology quality. Evaluating the included articles revealed that the intervention methods should be fully in line with the characteristics of the participants and the role of the cause of violence in the choice of intervention should not be ignored. Interventions are not superior to each other, because they are selected based on the type of violence and the target group. Further research using rigorous designs should be done to assess the effectiveness of existing methods to facilitate reductions in IPV exposure.

Acknowledgment

The research reported in this publication was supported by the Elite Researcher Grant Committee under award number 971358 from the National Institutes for Medical Research Development (NIMAD), Tehran, Iran.

Conflict of Interest

The corresponding author reports grants from the National Institutes for Medical Research Development (NIMAD) during this study. Other authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Aghakhani N, Sharif Nia H, Moosavi E, Eftekhari A, Zarei A, Bahrami N, et al. Study of the Types of Domestic Violence Committed Against Women Referred to the Legal Medical Organization in Urmia - Iran. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2015;9(4):e2446. doi: 10.17795/ijpbs-2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghazizadeh A. Domestic violence: a cross-sectional study in an Iranian city. East Mediterr Health J. 2005;11(5-6):880–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lipsky S, Caetano R, Field CA, Bazargan S. Violence-related injury and intimate partner violence in an urban emergency department. J Trauma. 2004;57(2):352–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000142628.66045.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruschi A, de Paula CS, Bordin IA. [Lifetime prevalence and help seeking behavior in physical marital violence] Rev Saude Publica. 2006;40(2):256–64. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102006000200011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams AE, Sullivan CM, Bybee D, Greeson MR. Development of the scale of economic abuse. Violence Against Women. 2008;14(5):563–88. doi: 10.1177/1077801208315529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmadi BA, Alimohamadian M, Golestan B, Bagheri Yazdi A, Shojaeezadeh D. Effects of domestic violence on the mental health of married women in Tehran. Journal of School of Public Health and Institute of Public Health Research. 2006 May 10;4(2):35–44. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abuse CO. CAADA insights into domestic abuse 1: A place of greater safety. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women: WHO clinical and policy guidelines. World Health Organization; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghazi Tabatabai M, Mohsen Tabrizi A, Marjai S. Studies on domestic violence against women. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hasegawa M, Bessho Y, Hosoya T, Deguchi Y. [Prevalence of intimate partner violence and related factors in a local city in Japan] Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi. 2005;52(5):411–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khadivzadeh T, Erfanian F. Comparison of domestic violence during pregnancy with the Pre-pregnancy period and its relating factors. The Iranian Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Infertility. 2011;14(4):47–56. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wathen CN, MacMillan HL. Interventions for violence against women: scientific review. Jama. 2003;289(5):589–600. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.5.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.PRISMA Flow Diagram Generator. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14.A revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials: cochrane. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown JB, Lent B, Schmidt G, Sas G. Application of the Woman Abuse Screening Tool (WAST) and WAST-short in the family practice setting. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(10):896–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norton LB, Peipert JF, Zierler S, Lima B, Hume L. Battering in pregnancy: an assessment of two screening methods. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85(3):321–5. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(94)00429-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oriel KA, Fleming MF. Screening men for partner violence in a primary care setting. A new strategy for detecting domestic violence. J Fam Pract. 1998;46(6):493–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tiwari A, Fong DY, Wong JY, Yuen KH, Yuk H, Pang P, et al. Safety-promoting behaviors of community-dwelling abused Chinese women after an advocacy intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(6):645–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark HM, Grogan-Kaylor A, Galano MM, Stein SF, Montalvo-Liendo N, Graham-Bermann S. Reducing intimate partner violence among Latinas through the moms’ empowerment program: An efficacy trial. JOFV. 2018 May 1;33(4):257–68. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta J, Falb KL, Lehmann H, Kpebo D, Xuan Z, Hossain M, et al. Gender norms and economic empowerment intervention to reduce intimate partner violence against women in rural Côte d'Ivoire: a randomized controlled pilot study. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2013;13:46. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-13-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graham-Bermann SA, Miller-Graff L. Community-based intervention for women exposed to intimate partner violence: A randomized control trial. J Fam Psychol. 2015;29(4):537–47. doi: 10.1037/fam0000091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coker AL, Bush HM, Cook-Craig PG, DeGue SA, Clear ER, Brancato CJ, et al. RCT Testing Bystander Effectiveness to Reduce Violence. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(5):566–78. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilbert L, El-Bassel N, Manuel J, Wu E, Go H, Golder S, et al. An integrated relapse prevention and relationship safety intervention for women on methadone: testing short-term effects on intimate partner violence and substance use. Violence Vict. 2006;21(5):657–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laeheem K. The effects of happy Muslim family activities on reduction of domestic violence against Thai-Muslim spouses in Satun province. KJSS. 2017 May 1;38(2):150–5. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Turner LA. The efficacy of an intimate partner violence prevention program with high-risk adolescent girls: a preliminary test. Prev Sci. 2012;13(4):384–94. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0240-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mejdoubi J, van den Heijkant SC, van Leerdam FJ, Heymans MW, Hirasing RA, Crijnen AA. Effect of nurse home visits vs. usual care on reducing intimate partner violence in young high-risk pregnant women: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e78185. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koziol-McLain J, Vandal AC, Wilson D, Nada-Raja S, Dobbs T, McLean C, et al. Efficacy of a Web-Based Safety Decision Aid for Women Experiencing Intimate Partner Violence: Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2018;19(12):e426. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi YJ, Orpinas P, Kim I, Ko KS. Korean clergy for healthy families: online intervention for preventing intimate partner violence. Glob Health Promot. 2019;26(4):25–32. doi: 10.1177/1757975917747878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glass NE, Perrin NA, Hanson GC, Bloom TL, Messing JT, Clough AS, et al. The Longitudinal Impact of an Internet Safety Decision Aid for Abused Women. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(5):606–15. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pronyk PM, Hargreaves JR, Kim JC, Morison LA, Phetla G, Watts C, et al. Effect of a structural intervention for the prevention of intimate-partner violence and HIV in rural South Africa: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2006;368(9551):1973–83. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69744-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sarnquist CC, Ouma L, Lang'at N, Lubanga C, Sinclair J, Baiocchi MT, et al. The Effect of Combining Business Training, Microfinance, and Support Group Participation on Economic Status and Intimate Partner Violence in an Unplanned Settlement of Nairobi, Kenya. J Interpers Violence. 2018:886260518779067. doi: 10.1177/0886260518779067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Falb KL, Annan J, Kpebo D, Cole H, Willie T, Xuan Z, et al. Differential Impacts of an Intimate Partner Violence Prevention Program Based on Child Marriage Status in Rural Côte d'Ivoire. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57(5):553–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raj A, Silverman JG, Klugman J, Saggurti N, Donta B, Shakya HB. Longitudinal analysis of the impact of economic empowerment on risk for intimate partner violence among married women in rural Maharashtra, India. Soc Sci Med. 2018;196:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abramsky T, Devries K, Kiss L, Francisco L, Nakuti J, Musuya T, et al. A community mobilisation intervention to prevent violence against women and reduce HIV/AIDS risk in Kampala, Uganda (the SASA! Study): study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2012;13:96. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sullivan CM. Using the ESID model to reduce intimate male violence against women. Am J Community Psychol. 2003;32(3-4):295–303. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000004749.87629.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galano MM, Grogan-Kaylor AC, Stein SF, Clark HM, Graham-Bermann SA. Posttraumatic stress disorder in Latina women: Examining the efficacy of the Moms' Empowerment Program. Psychol Trauma. 2017;9(3):344–51. doi: 10.1037/tra0000218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Graham-Bermann SA, Miller LE. Intervention to reduce traumatic stress following intimate partner violence: an efficacy trial of the Moms' Empowerment Program (MEP) Psychodyn Psychiatry. 2013;41(2):329–49. doi: 10.1521/pdps.2013.41.2.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Glass N, Eden KB, Bloom T, Perrin N. Computerized aid improves safety decision process for survivors of intimate partner violence. J Interpers Violence. 2010;25(11):1947–64. doi: 10.1177/0886260509354508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carey MP, Carey KB, Maisto SA, Gordon CM, Weinhardt LS. Assessing sexual risk behaviour with the Timeline Followback (TLFB) approach: continued development and psychometric evaluation with psychiatric outpatients. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12(6):365–75. doi: 10.1258/0956462011923309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mikton C. Preventing intimate partner and sexual violence against women: taking action and generating evidence. Inj Prev. 2010;16(5):359–60. doi: 10.1136/ip.2010.029629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hindin MJ, Kishor S, Ansara DL. Intimate partner violence among couples in 10 DHS countries: Predictors and health outcomes. Macro International Incorporated 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fox VC. Historical perspectives on violence against women. J Int Womens Stud. 2002;4(1):15–34. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davoudi F, Rasoulian M, Asl MA, Nojomi M. What do victims of physical domestic violence have in common? A systematic review of evidence from Eastern Mediterranean countries. WHB. 2014 Jun;1(2) [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vyas S, Watts C. How does economic empowerment affect women's risk of intimate partner violence in low and middle income countries? A systematic review of published evidence. Journal of International Development: The Journal of the Development Studies Association, 21. 2009;21(5):577–602. [Google Scholar]

- 45.National Family Health Survey, India. Fact Sheets for Key Indicators Based on Final Data. 2017. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goetz AM, Sen Gupta R. Who takes the credit? Gender, power and control over loan use in rural credit programmes in Bangladesh. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heise LL, Kotsadam A. Cross-national and multilevel correlates of partner violence: an analysis of data from population-based surveys. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(6):e332–40. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Laeheem K, Baka D. A study of youth’s violent behavior in the three southern border provinces of Thailand. NDJ. 2012;52(1):159–87. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Olds DL. Prenatal and infancy home visiting by nurses: From randomized trials to community replication. Prevention Science. 2002 Sep 1;3(3):153–72. doi: 10.1023/a:1019990432161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alone N. The First Report of the White House Task Force to Protect Students from Sexual Assault. April 2014. Washington DC: The White House; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Banyard VL, Plante EG, Moynihan MM. Bystander education: Bringing a broader community perspective to sexual violence prevention. JCOP. 2004 Jan;32(1):61–79. [Google Scholar]