Abstract

Background/Aims:

To assess the effectiveness, burden and safety of two categories of treatment for central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO): intravitreal injections of anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (anti-VEGF) and Dexamethasone (Ozurdex).

Methods:

A retrospective analysis of Medisoft Electronic Patient Record (EPR) data from 27 NHS sites in the UK identified 4619 treatment naive patients with a single mode of treatment for macular oedema secondary to CRVO. Statistics describing the overall CRVO patient cohort and individual patient sub-populations stratified by treatment type were generated. Mean age at baseline, gender, ethnicity, social deprivation and visual acuity (VA) follow-up was reported. Absolute and change in VA using Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Score are used to describe treatment effectiveness, the number of injections and visits used to describe treatment burden and endophthalmitis rates as a marker of treatment safety.

Results:

Mean VA was 47.9 and 45.3 EDTRS letters in the anti-VEGF and Ozurdex groups, respectively. This changed to 57.9 / 53.7 at 12-months, 58.3 / 46.9 at 18-months and 59.4 at 36-months for the anti-VEGF group alone. Mean number of injections were 5.6 / 1.6 at 12-months, 6.0 / 1.7 at 18-months, and 7.3 at 36-months for the anti-VEGF group alone. Endophthalmitis rates were 0.003% (n = 4) for the anti-VEGF group and 0.09% (n = 1) for the dexamethasone group.

Conclusions:

VA improvements were greater and more sustained with anti-VEGF treatment. Lower starting acuity resulted in bigger gains in both groups, whilst higher starting acuity resulted in higher VA at 36-months. Although treatment burden was greater with anti-VEGF, Ozurdex was associated with higher rates of endophthalmitis.

Introduction

Central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) impedes blood supply to the retina, causing retinal ischaemia, oedema and loss of vision1. It commonly occurs in older people, generally over the age of 65-years with an incidence rate of 0.1–0.4%1,2. Although a small number of patients may experience some spontaneous improvement, most patients will exhibit a worsening in vision over time3. The natural course of CVRO dictates that final visual outcome at 40-months will not be greater than 73-letters3 as measured using the ETDRS (Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study) letter chart4. Secondary macular oedema (MO) is the most common cause of visual loss in CRVO, with 75% of patients developing this complication within 2-months of diagnosis and 100% of these developing visual loss3.

Current treatment options for CRVO include ocular anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) injections and steroid implants. Treatment with anti-VEGF injections is often preferred as a first line treatment with two licenced options, Ranibizumab (Lucentis, Genetech Inc, South San Fransisco, CA, USA) and Aflibercept (Eylea, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc, Tarrytown, NY, USA), available for intravitreal use to treat MO secondary to CRVO3. Although the unlicensed use of Bevacizumab (Avastin, Genentech Inc) to treat MO secondary to CRVO is supported by small case series, there are no large scale randomised controlled trial data currently available3.

The CRUISE study assessed the benefits of Ranibizumab treatment in 392 patients diagnosed with MO secondary to CRVO. It was reported that monthly injections of either 0.3 or 0.5mg during the first 6-months resulted in a mean gain of 13.9 ETDRS letters. Treatment-as-required for the following 6-months, with a mean of 3.3 injections, resulted in maintenance of the initial EDTRS gains5. However, extension studies for CRUISE, namely HORIZON and RETAIN, have reported that these initial gains in visual acuity (VA) are not maintained following long-term treatment-as-required for up to a further 2- and 4-years respectively6,7. The HORIZON study reported VA as −5.2 and −4.1 ETDRS letters with either 0.3 or 0.5mg, whereas this was 0-letters in the RETAIN study. However, it is important to note that the number of patients from the original cohort included in these follow-up studies reduced to 337 and 32 in HORIZON and RETAIN respectively.

The two major clinical trials evaluating the effects of Aflibercept on CRVO are COPERNICUS8,9 and GALILEO10,11. In the COPERNICUS study, baseline VA was reported as 50.7 ETDRS letters when patients began to receive monthly 2mg injections. Over the course of 2-years VA increased by 17.3-letters after 24-weeks, reducing slightly to 16.2-letters after 52-weeks with a further slight reduction at 100-weeks of 13-letters, albeit a gain from baseline8,9. A similar story was reported from the GALILEO trial which outlined improvements in VA from a baseline of 18.0, 16.9 and 13.7-letters at 24-, 52- and 76-weeks respectively10,11. Whilst it may appear that VA improvements are maintained with Aflibercept over Ranibizumab, it is important to note that there is insufficient data to confirm this. Clinical trials assessing the benefits of Aflibercept have yet to follow-up patients for the same length of time as the Ranibizumab trials.

Intravitreal steroid implants are an alternative treatment to anti-VEGF injections. Dexamethasone implants (Ozurdex, Allergan Inc, Irvine, CA, USA) received Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 2009 for the treatment of MO secondary to CRVO or branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO). Dexamethasone may be preferred in those that do not want monthly injections, have a higher risk of glaucoma or younger phakic patients3. The GENEVA trial evaluated the benefit of dexamethasone in treating CRVO over a 12-month period. Following the first treatment, there was an initial gain of 10-letters from baseline by month 2 which decreased to no mean change at month 6. By 12-months, following a second treatment, there was a mean increase of 2-letters from baseline VA12,13.

To date, no large randomised clinical trials have compared the effects of anti-VEGF and steroid implants in treating CRVO. There is increasing potential for ‘big datasets’ to provide a powerful tool to evaluate the effectiveness of retinal treatments in clinical practice. The UK EMR (electronic medical record) Users Group has previously demonstrated that clinical trial data may not be replicated in real world practice, with fewer observed treatments and worse visual outcomes reported in age-related macular degeneration (AMD)14 and branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) (Gale et al, in press) studies. Therefore, this current study aims to evaluate the effectiveness, burden and safety of the two main treatment options for CRVO: intravitreal anti-VEGF and intravitreal dexamethasone (Ozurdex). Utilizing the sizable UK EMR database has enabled the evaluation of a much larger CRVO cohort than previously documented. Our first objective was to evaluate treatment effectiveness; are the same positive VA outcomes observed in patients treated outside of clinical trials as those within and how does this differ with treatment type. The second objective was to compare treatment burden between the two treatment types with the third objective comparing the safety of the two treatment types.

Materials and Methods

Design

Twenty-seven NHS sites contributing to the Medisoft Electronic Medical Record (EMR) system to record treatments of retinal diseases agreed to contribute data to this study relating to CRVO. Data were recorded between 01/02/2002 and 13/12/2018. Length of follow-up varied according to when the patient was first entered onto the system and how long the patient’s treatment and VA assessments were recorded. The date of exit from the study was defined as either the date the last VA measurement was received or the date of the last VA measurement prior to any other treatment modality or cataract surgery.

Appropriate institutional review board approval was obtained at the last author’s institution. Signed permission was returned from the lead clinician and Caldicott guardian (the clinician responsible for data protection in an NHS trust) at each participating trust. The study is registered on a list of studies using anonymised data at the lead clinician’s home institution.

Participants

Data were recorded for patients receiving either anti-VEGF or Ozurdex treatment for CRVO. Any patients who switched to a different treatment option during the study period were censored and from that point forward, their data was no longer included in the analysis. All records with missing information, including age and gender, were excluded from the study. Other exclusion criteria included patients not treatment naïve, patients receiving treatments for other conditions or treatments as part of masked randomised trials, patients receiving pan retinal photocoagulation, diagnoses of ‘clinically significant macular oedema’ and patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) as it could not be certain if they were being treated for CRVO. Patients receiving intravitreal triamcinolone were also excluded because of the low number of eyes initiating on this treatment along with any patients with a record of cataract surgery in the three months before the first treatment for CRVO.

Procedures

Data on age (years), ethnicity (as recorded in the local patient administration system) and social deprivation (based on the index of multiple deprivation) was obtained for all patients. VA was performed as part of routine clinical practice using an Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) chart to give an ETDRS letter score4, Snellen and LogMar acuity. All numerical values were converted to an ETDRS letter score using a standard algorithm15. Poor baseline VA was recorded in a number of eyes as below 0-letters (Table 1). Whilst the number of eyes affected is reported, they were excluded from the analysis of treatments based on pooled VA measurements.

Table 1:

Demographic information for 4,698 eyes diagnosed with CRVO stratified by treatment type, including mean visual acuity changes over time along with data relating to treatment burden and the number of eyes switching treatment.

| Anti-VEGF (n = 4093,84% total) |

Ozurdex (n = 605,16% total) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (% males) | 53.0 | 49.8 | |||

| Age | Mean | 73.1 | 73.43 | ||

| SD | 13.1 | 11.3 | |||

| IQR | 66–83 | 66–82 | |||

| Mean Age | 1st quintile | 52.5 | 56.3 | ||

| 2nd quintile | 67.8 | 68.2 | |||

| 3rd quintile | 74.5 | 74.4 | |||

| 4th quintile | 80.5 | 80.3 | |||

| 5th quintile | 87.7 | 87.1 | |||

| Ethnicity (%) | White | 2454 (60.0) | 274 (45.3) | ||

| Mixed | 5 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | |||

| Asian | 138 (3.4) | 14(2.3) | |||

| Black | 61(1.5) | 3 (0.5) | |||

| Chinese | 5 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Other | 33 (0.8) | 8(1.3) | |||

| Not recorded | 1390(34.0) | 305 (50.4) | |||

| Social Deprivation % | 1st quintile | 19.2 | 18.8 | ||

| 2nd quintile | 18.9 | 16.0 | |||

| 3rd quintile | 18.8 | 14.2 | |||

| 4th quintile | 17.3 | 18.5 | |||

| 5th quintile | 17.5 | 16.5 | |||

| n/a | 8.4 | 15.9 | |||

| Baseline acuity <0 ETDRS letters | CF | 276 | 43 | ||

| HM | 222 | 17 | |||

| LP | 14 | 0 | |||

| NLP | 4 | 0 | |||

| Mean VA in ETDRS letters (n) | At baseline | 47.9 (3577) | 45.3 (545) | ||

| At 6-months | 56.2 (1295) | 46.4(119) | |||

| At 12-months | 57.9 (877) | 53.7 (60) | |||

| At 18-months | 58.3 (558) | 46.9 (47) | |||

| At 24-months | 58.7 (407) | 51.3(23) | |||

| At 36-months | 59.4(219) | 51.0(9) | |||

| Poor VA outcomes at the end of follow-up | CF | 119 | 35 | ||

| HM | 83 | 22 | |||

| LP | 18 | 1 | |||

| NLP | 18 | 6 | |||

| Mean total visits and treatments given per patient | Visits | Treatments | Visits | Treatments | |

| At 6-months | 5.29 | 3.8 | 3.83 | 1.28 | |

| At 12-months | 7.76 | 5.6 | 5.48 | 1.58 | |

| At 18-months | 9.77 | 6.02 | 6.49 | 1.73 | |

| At 24-months | 11.02 | 6.62 | 7.00 | 1.78 | |

| At 36-months | 11.93 | 7.06 | 7.31 | 1.81 | |

| Treatment switching to: | Anti-VEGF | n/a | 276 | ||

| Ozurdex | 144 | n/a | |||

| Triamcinolone | 12 | 0 | |||

| Macular laser | 29 | 7 | |||

Anti-VEGF: Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor; ETDRS: Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study; VA: Visual Acuity; CF: Counting Fingers; HM: Hand Movements; LP: Light Perception; NLP: No Light Perception.

Analysis

To compare the effectiveness of the two treatment modalities, absolute VA and change in VA from baseline were plotted for all patients within the two treatment groups over three years at approximately monthly intervals. Numbers were sufficiently high in both treatment groups to allow assessment of the impact of age and VA at baseline by stratification into quintiles. Treatment burden was evaluated using number of visits and number of injections. Treatment safety was calculated from endophthalmitis rates for both anti-VEGF and Ozurdex categories.

Results

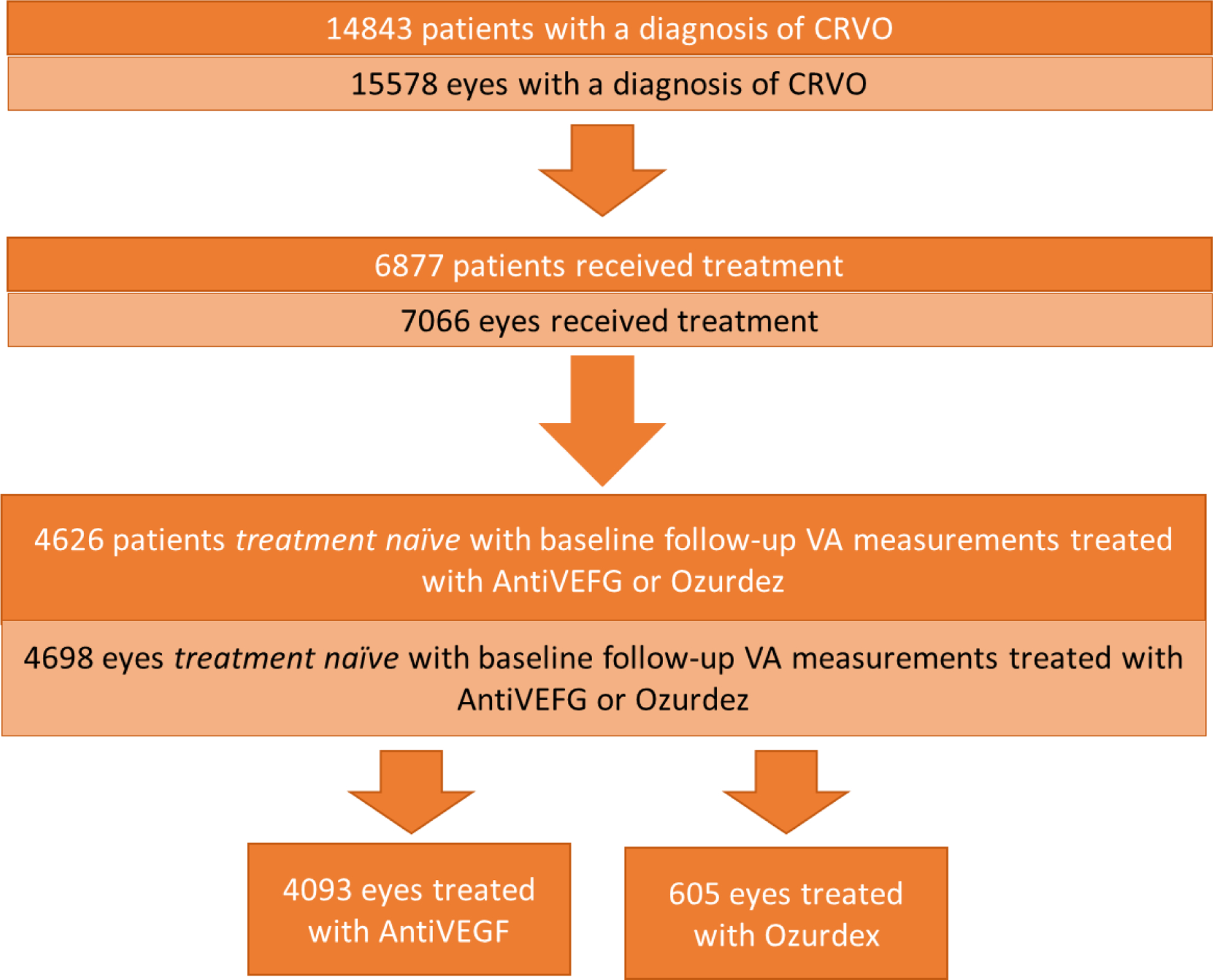

A total of 4698 eyes from 4626 patients were treated for CRVO (Figure 1). Patients were allocated into one of two groups according to the treatment received. Group 1, the ‘Anti-VEGF’ group included 4093 eyes treated with ranibizumab (Lucentis), bevacizumab (Avastin) or aflibercept (Eylea) and group 2, the ‘Ozurdex’ group included 605 eyes treated with dexamethasone (Ozurdex).

Figure 1:

CONSORT flow diagram, for entire CRVO patient population with the final allocation to the Anti-VEGF or Ozurdex treatment groups.

Demographics of the CRVO cohort are outlined in Table 1. Mean age and gender split were equally matched between the Anti-VEGF (73.1 years; 53% males) and Ozurdex (73.43 years; 49.8 % males) treatment groups. Recorded ethnicity and the spread of social deprivation were also closely matched between the two groups.

Treatment Effectiveness

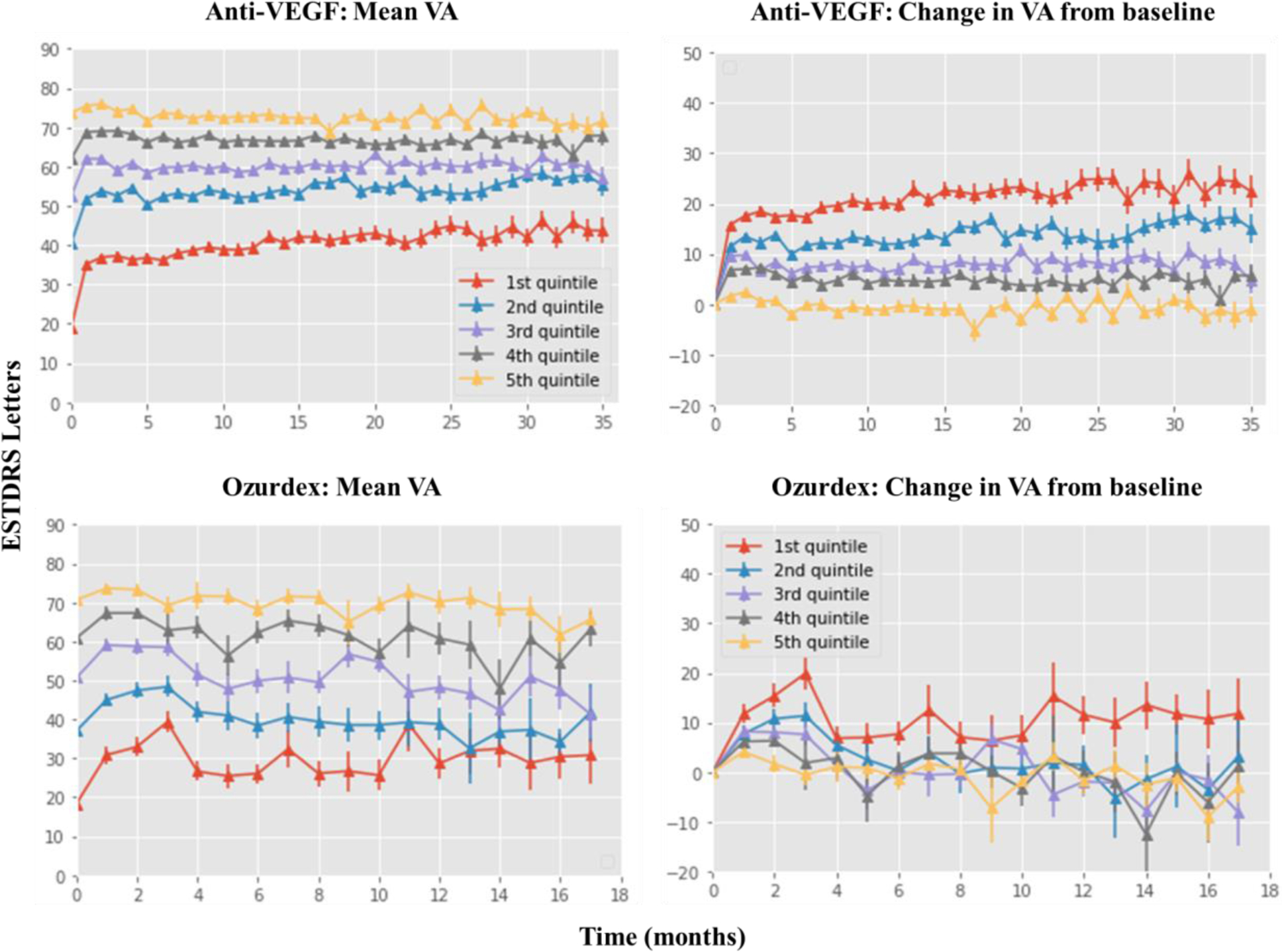

To determine the effectiveness of CRVO treatment, absolute and change in VA from baseline was assessed for the two treatment groups. No interpolation is performed on this data, so the monthly totals are smaller than the total cohort size (Table 1). Baseline mean VA was 47.9 and 45.3-EDTRS letters for the anti-VEGF and Ozurdex groups, increasing to 57.9 and 53.7-letters at 12-months and 58.3 and 46.9-letters at 18-months (Figure 2). VA at 36-months was 59.4-letters for the anti-VEGF group alone. It is important to note that the sample size for both cohorts is reduced by the 36-month follow-up, with 219 patients remaining in the anti-VEGF and 9 patients in the Ozurdex group (Table 1).

Figure 2:

Visual acuity (VA) changes over time. Line graph showing the mean VA at monthly intervals on the left-hand side with the change in VA shown on the right-hand side. Results for the anti-VEGF group are plotted on the top row with the Ozurdex group shown on the bottom row. VA is plotted as the number of ETDRS letters, stratified by baseline VA. Numbers for the Oxurdex cohort are very low. For all four plots, values are carried forward between months where no measurement was made but not beyond the last measurement.

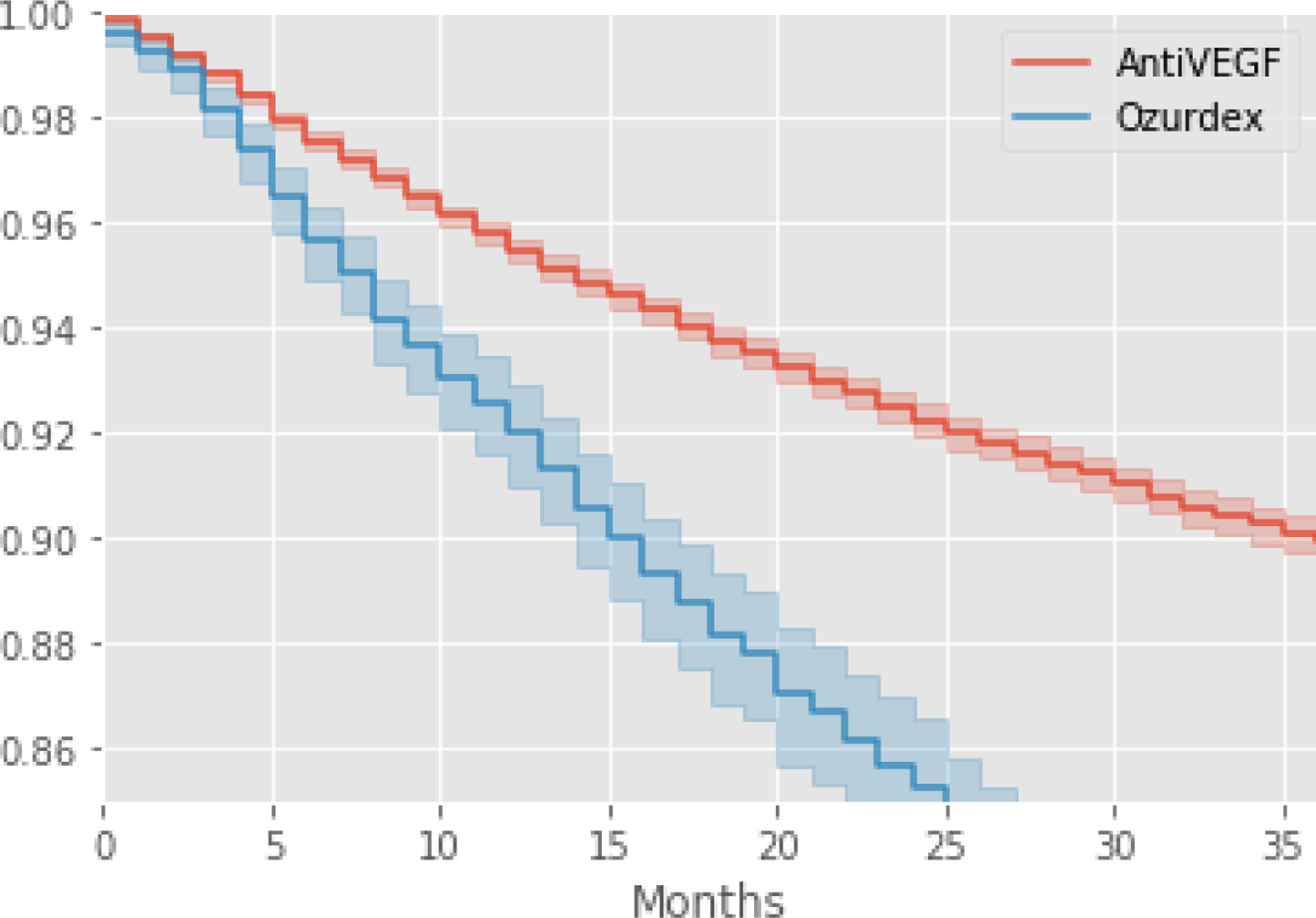

Data also reveal that a lower starting VA resulted in a larger gain over time whereas a higher starting VA resulted in a higher ending VA by 36-months (Figure 2). A Kaplan-Meier estimator was used to predict the time at which a 15-letter reduction in VA performance would be observed between the two treatment groups, revealing that treatment with Ozurdex would result in a faster loss in VA compared to Anti-VEGF (Figure 3).

Figure 3:

Kaplan-Meier estimation of the time to 15-letter loss stratified by treatment type. Estimates for treatment with anti-VEGF is shown in red with Ozurdex shown in blue.

Eyes with poor outcomes.

The total number of eyes with a final VA of 0 ETDRS letters was 238 in the anti-VEGF group and 64 in the Ozurdex group, allocated into one of the following categories: counting fingers (CF), hand movements (HM), light perception (LP) or no light perception (NLP) (Table 1).

Treatment Burden

Treatment burden was determined by the mean number of treatments and visits, stratified by treatment type. There were more treatments and visits required with anti-VEGF (Treatments = 3.8; Visits = 5.29) compared to Ozurdex (Treatments = 1.28; Visits = 3.83) within the first 6-months (Table 1). At 36-months, although the mean number of visits increased with Ozurdex treatment, anti-VEGF was still associated with more treatments and visits (anti-VEGF: Treatments = 7.06, Visits = 11.93; Oxurdex: Treatments = 1.81, Visits = 7.31).

Treatment Safety

Treatment safety was determined by the number of endophthalmitis rates between the two treatment types. Of the 30,644 anti-VEGF injections administered within the follow-up period, 4 cases of endophthalmitis were observed, at a rate of 0.01%. Of the 1,084 Ozurdex injections administered, 1 case of endophthalmitis was observed, at a rate of 0.2%.

Discussion

This is the largest study to report on the outcomes from two treatment types for CRVO, anti-VEGF and Ozurdex, using a “real-world” dataset. With a cohort of 4,626 UK patients, 229 of whom were followed up over three years, we assessed the effectiveness, burden and safety of the two treatment types. We reveal that gains in visual acuity (VA) were greater and more sustained with anti-VEGF compared with Ozurdex treatment. Whilst Anti-VEGF treatment resulted in a greater number of treatment visits compared with Ozurdex, endophthalmitis rates were in fact reduced.

Relative gains in VA during the first 6-months with anti-VEGF treatment were lower in this real-world dataset compared to the key clinical trials, with an increase of +8.1 ETDRS letters compared to increases of +13.9 in CRUISE5, +17.3 in CORPERNICUS8,9 and +18.0 in GALILEO10,11. In contrast, treatment with Ozurdex revealed slightly greater VA gains in the first 6-months, with an increase of 1.1 ETDRS letters compared to no mean change from baseline in the GENEVA trial12,13.

Although we found that mean baseline VA was higher for patients treated with anti-VEGF (47.9) compared with Ozurdex (45.3), this is also lower than the baseline VAs reported in the CRUISE (48.3), CORPERNICUS (50.7) and GENEVA (54.3) clinical trials. Notwithstanding, we show that patients with the lowest baseline VA show the greatest absolute improvement, whilst patients with a higher baseline VA have the best outcomes. In line with previous research, we also report that patients with worse starting VA did not reach the endpoint VA as those with better starting VA16.

The number of patients with severe visual loss (counting fingers or less) by the end of follow-up was considerably greater with anti-VEGF (238) compared with Ozurdex (64) treatment. Although, this difference is likely due to reflect the reduced number of patients remaining in the two treatment cohorts at this time. However, patients were more likely to improve when treated with anti-VEFG, as the Ozurdex patients either did not improve or failed to maintain their improvement. We also show that the estimated time until a 15 letter loss in VA is reported is slower with anti-VEGF compared to Ozurdex treatment (Figure 3).

It is important to appreciate that there are different starting VA which may affect this outcome. This effect is not related to the treatment for cataracts since these patients were excluded. It should be noted that the shift in the mean VA measurement over time may not reflect the trajectories of individual patients but the changing composition of the cohort as more and more patients are progressively lost to follow-up or switched to alternative therapies. In this cohort, 185 anti-VEGF and 283 Ozurdex patients switched from their original form of treatment over the course of the study (Table 1). Of the 283 Ozurdex patients, 276 switched to anti-VEGF treatment. One possible explanation for this large number in switching could be due to the approval of anti-VEGF in the treatment of RVO in 20133.

Treatment burden was found to be greater with anti-VEGF treatment for CRVO, with a mean of 3.8 treatments in the first 6-months compared with 1.28 treatments with Ozurdex. Nevertheless, this must be considered in the context of the better VA outcomes with anti-VEGF. However, compared with CRUISE, who reported a mean of 5.8 injections within the first 6-months5, fewer injections were seen in this real-world data. In terms of the number of visits, there were also more required with anti-VEGF (5.29) compared with Ozurdex (3.83) treatment during the first 6-months. Although, it is worth noting that the number of visits required reduces over time, a pattern also found in the CRUISE study5.

Treatment safety in these two cohorts was assessed by the number of endophthalmitis rates, which were extremely low with both anti-VEGF and Ozurdex. Albeit, when the two treatments are compared, endophthalmitis rates are 10 times lower with anti-VEGF. Although, it is possible that emergency prescriptions for endophthalmitis are not recorded in our study and thus may be under reported in this data, there were no reported cases within 12-months of the CRUISE study5.

By using real-world data, this study has the advantages and disadvantages of studies reporting on the routine care received by patients outside of the controlled environment of clinical trials. A particular difficulty is that of missing data. Not all patients are assessed for visual acuity at the same point in time, many patients are lost to follow-up and there is no way to determine whether the data is censored because of patients who have moved, declined further treatment or died. There was more missing data and switching for the dexamethasone. Demographic data show that the patients in the two treatment groups were of similar age, and had similar mixes of gender, ethnicity and had similar scores for social deprivation.

In conclusion, we report visual acuity improvements in a large cohort of CRVO patients treated with either anti-VEGF or Ozurdex, but they were higher and more sustained with anti-VEGF treatment. Comparably with other retina diseases, including BRVO and nAMD, lower starting acuity resulted in bigger gains in both groups, but higher starting acuity resulted in higher visual acuity at 36-months. Both groups had relatively low rates of endophthalmitis, with Ozurdex associated with higher rates. The data reported here are from the largest study yet in the UK for patients with this condition and the outcomes should help inform clinician and patient choice for treatment and the planning of services.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Anti-VEGF

Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor

- BRVO

Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion

- CF

Counting Fingers

- CRVO

Central Retinal Vein Occlusion

- DR

Diabetic Retinopathy

- ETDRS

Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study

- HM

Hand Movements

- LP

Light Perception

- MBRVO

Macular Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion

- NLP

No Light Perception

- RVO

Retinal Vein Occlusion

- VA

Visual acuity

References:

- 1.Mishra SK, Gupta A, Patyal S, et al. Intravitreal dexamethasone implant versus triamcinolone acetonide for macular oedema of central retinal vein occlusion: Quantifying efficacy and safety. Int J Retin Vitr. 2018;4(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s40942-018-0114-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayreh SS, Zimmerman MB, Podhajsky P. Incidence of various types of retinal vein occlusion and their recurrence and demographic characteristics. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994;117(4):429–441. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(14)70001-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clinical Guidelines Retinal Vein Occlusion (RVO) Guidelines.; 2015.

- 4.ETDRS. Photocoagulation for diabetic macular edema: Early treatment diabetic retinopathy study report number 1 early treatment diabetic retinopathy study research group. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985;103(12):1796–1806. 10.1001/archopht.1985.01050120030015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campochiaro PA, Brown DM, Awh CC, et al. Sustained benefits from ranibizumab for macular edema following central retinal vein occlusion: Twelve-month outcomes of a phase III study. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(10):2041–2049. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.02.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heier JS, Campochiaro PA, Yau L, et al. Ranibizumab for macular edema due to retinal vein occlusions: Long-term follow-up in the HORIZON trial. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(4):802–809. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campochiaro PA, Sophie R, Pearlman J, et al. Long-term outcomes in patients with retinal vein occlusion treated with ranibizumab: The RETAIN study. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(1):209–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.08.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown DM, Heier JS, Clark WL, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept injection for macular edema secondary to central retinal vein occlusion: 1-year results from the phase 3 copernicus study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;155(3):429–437. e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.09.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heier JS, Clark WL, Boyer DS, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept injection for macular edema due to central retinal vein occlusion: Two-year results from the COPERNICUS study. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(7):1414–1420. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogura Y, Roider J, Korobelnik JF, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept for macular edema secondary to central retinal vein occlusion: 18-month results of the phase 3 GALILEO study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;158(5):1032–1038. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korobelnik JF, Holz FG, Roider J, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept injection for macular edema resulting from central retinal vein occlusion: One-year results of the phase 3 GALILEO study. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(1):202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haller JA, Bandello F, Belfort R, et al. Dexamethasone intravitreal implant in patients with macular edema related to branch or central retinal vein occlusion: Twelve-month study results. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(12):2453–2460. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haller JA, Bandello F, Belfort R, Blumenkranz MS. Randomized, Sham-Controlled Trial of Dexamethasone Intravitreal Implant in Patients with Macular Edema Due to. OPHTHA. 2010;117(6):1134–1146. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.03.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Group WC for the UA-RMDEU. The neovascular age-related macular degeneration database: Multicenter study of 92 976 ranibizumab injections: Report 1: Visual acuity manuscript no. 2013–568. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(5):1092–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gregori NZ, Feuer W, Rosenfeld PJ. NOVEL METHOD FOR ANALYZING SNELLEN VISUAL ACUITY MEASUREMENTS. Retina. 2010;30(7):1046–1050. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181d87e04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Airody A, Venugopal D, Allgar V, Gale RP. Clinical characteristics and outcomes after 5 years pro re nata treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration with ranibizumab. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015;93(6):e511–e512. doi: 10.1111/aos.12618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]