Abstract

Introduction:

A growing number of dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease (DIAD) cases have become known in Latin American (LatAm) in recent years. However, questions regarding mutation distribution and frequency by country remain open.

Methods:

A literature review was completed aimed to provide estimates for DIAD pathogenic variants in the LatAm population. The search strategies were established using a combination of standardized terms for DIAD and LatAm.

Results:

Twenty-four DIAD pathogenic variants have been reported in LatAm countries. Our combined dataset included 3583 individuals at risk; countries with highest DIAD frequencies were Colombia (n = 1905), Puerto Rico (n = 672), and Mexico (n = 463), usually attributable to founder effects. We found relatively few reports with extensive documentation on biomarker profiles and disease progression.

Discussion:

Future DIAD studies will be required in LatAm, albeit with a more systematic approach to include fluid biomarker and imaging studies. Regional efforts are under way to extend the DIAD observational studies and clinical trials to Latin America.

1 ∣. INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by the neuropathologic hallmarks of amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, with the clinical course manifested as progressive loss of cognition and independence in activities of daily living. AD is also the most frequent neurodegenerative disease and results in ≈50 million people living with dementia globally.1-3 The number of persons with AD dementia is projected to more than triple to 152 million by 2050, with the potential to overwhelm families, communities, public health care systems, and economies throughout the world, especially in low and middle income countries.4,5 Over the last decade, Latin American (LatAm) countries have reported a high dementia prevalence, ranging from 6.2 to 12.1%, among individuals aged 65+ years.6,7 Furthermore, the region will experience the greatest impact of dementia in the next decade, and the number of people with dementia is expected to nearly quadruple in this region by 2050.6-9 However, the impact of genetic and social determinants of health remain poorly understood in LatAm populations.

Worldwide, the vast majority of AD dementia cases are considered sporadic and generally occur in older ages (>60), while a small proportion (<1%) of AD cases are caused by pathogenic mutations in the amyloid precursor protein (APP), presenilin 1 (PSEN1), or presenilin 2 (PSEN2) genes with almost 100% penetrance and earlier onset,10,11 known as dominantly inherited AD (DIAD).

Although smaller in number, due to the significant early onset, individuals and families with DIAD mutations face a higher burden of disease relative to late onset AD. DIAD is more often associated with a sense of unexpected loss of independence in midlife and difficulty in meeting family financial responsibilities.12,13 Moreover, family members often have higher levels of disease awareness and anxiety related to uncertainty about the future.14 DIAD frequency and correlates of impact in LatAm remain to be determined.

As research efforts have moved earlier in the disease continuum to target asymptomatic stages of AD, identifying participants with preclinical sporadic AD is challenging and costly because a large number of cognitively normal individuals must be screened with expensive diagnostics to find adequate numbers of participants with elevated cerebral amyloid, and not all of those who are deemed Aβ-positive will develop dementia. DIAD offers an alternative to early case identification facilitating research in AD.15 As a result, DIAD provides a unique translational model in AD research and may hold the key to understanding disease pathogenesis and the identification of effective treatments.16

In 2008, the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network observational study (DIAN or DIAN OBS) was established to create an international network of centers to facilitate the study of the very rare population of DIAD. To enable AD trials for this population, the DIAN Trials Unit (DIAN-TU) was launched in 2012 to implement interventional therapeutic trials in DIAD participants and to help expedite identification of effective disease-modifying therapies for DIAD that also could be generalizable to the sporadic AD population.15,16 Since inception, both DIAN OBS and the DIAN-TU have grown rapidly and increased the number of sites.15 The DIAN Expanded Registry (DIAN EXR), has helped in the identification and outreach to newly identified families featuring these rare AD mutations, creating a cohort-ready population that may accelerate study recruitment.

The DIAN network has also increased collaboration in LatAm. LatAm centers are being established for the DIAN OBS and DIAN-TU in the region to offer DIAD families opportunities to participate in longitudinal research and experimental therapies to prevent, delay, or treat AD. As DIAN establishes new sites in LatAm, a cohort-ready population will be critical for recruitment and enrollment in upcoming observational studies and clinical trials.17 Although a growing number of families with pathogenic mutations have become known in Mexico and Central and South American countries in recent years, little is known collectively about mutation frequency by country, family reports, number of family members, and clinical phenotype of these mutations in LatAm countries. Therefore, we aimed to systematically review the reported DIAD cases in Mexico and Central and South American countries to elucidate reported pathogenic variants by country, number of reported families, age at onset, clinical phenotype (initial cognitive symptoms and the frequency of additional neurological features), and disease progression.

In this report, literature findings were complemented and updated by new observations from local researchers in LatAm. This report may help to clarify the frequency and clinical presentations of DIAD in LatAm and thus inform the future development of observational studies and clinical trials in LatAm populations.

2 ∣. METHODS

We identified and described DIAD pathogenic variants reported in LatAm populations. The search strategy was developed with assistance from a research committee formed by a medical librarian, representatives from multiple LatAm countries (local dementia experts and clinical researchers), DIAN researchers, and other stakeholders with expertise in AD genetics. The research committee provided feedback and guidance on the proposed search strategies, selection criteria, and data analysis approach.

The search strategies were established using a combination of standardized terms and key words, including but not limited to: (Latin America OR Central America OR South America OR Mexico) AND (Alzheimer disease) AND (pedigree OR autosomal dominant inheritance OR presenilin 1 OR presenilin 2 OR amyloid precursor protein). The search was run in December 2019 using a librarian-created filter for non-animal studies in the databases Ovid Medline (1946–present), Embase (1947–present), Scopus (1960–present), Cochrane Central, Scielo, Clinicaltrials.gov, and LILACS (1982–present). Studies in English, Spanish, French, and/or Portuguese were included to reflect all possible reports from the region. A total of 1693 citations were exported to Endnote. Duplicate citations (n = 766) were accurately identified and removed for a total of 922 unique citations. Full electronic search strategies are provided in the Supporting Information. To supplement database searches, additional peer-reviewed published studies (n = 5) were identified through the AD/Frontotemporal Dementia Mutation Database (AD&FTDMDB),18 the Alzheimer Research Forum Database (ALZFORUM),19 and relevant studies recommended by the authors’ committee.

All citations retrieved by these methods (n = 927) were compiled and screened for appropriateness against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies were included if they reported on (1) clinical features of DIAD families carrying PSEN1, PSEN2, and APP mutations; (2) family reports from populations living in LatAm countries; and (3) variants with possible or proven pathogenicity as described in AD&FTDMDB and ALZFORUM. Reports describing non-pathogenic PSEN1, PSEN2, or APP mutations or variants with unknown/uncertain significance (VUS) were excluded from this study.

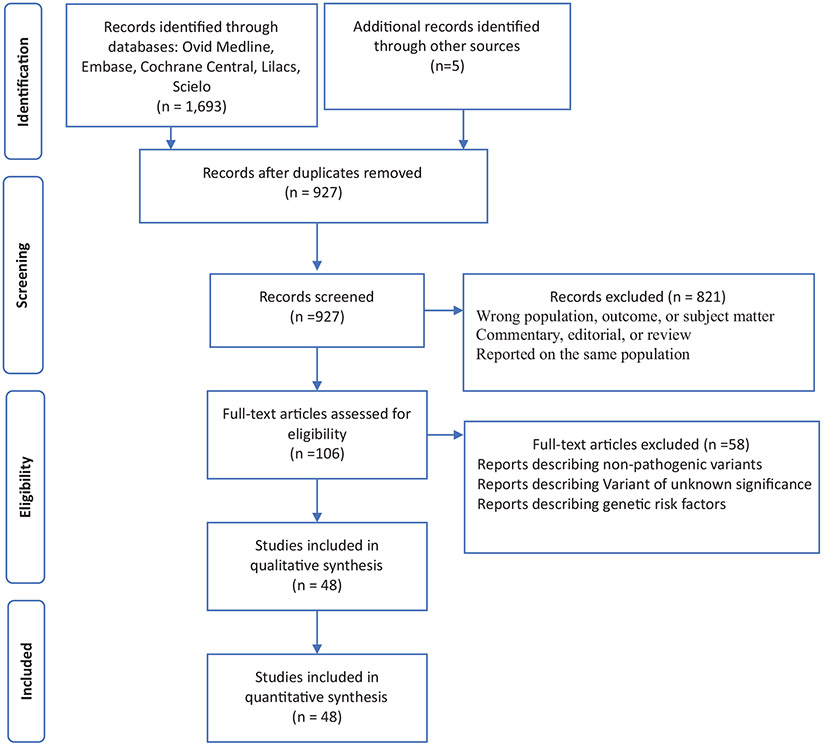

Studies that met the inclusion criteria (n = 106) underwent full-text assessment, a second screening stage to confirm validity. Forty-eight peer-reviewed publications were selected for the final analysis (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Diagram of the study selection process for the systematic review

Dementia experts and clinical researchers from LatAm (at least one per country) were asked to provide raw data on previously reported DIAD cases in the LatAm region. Additional raw data from unreported DIAD family members with confirmed pathogenic variants was obtained from researchers in the region and included for the final analysis. To avoid potential double reporting, the additional pedigrees for each DIAD pathogenic variant were manually examined for possible duplicates by members of the research committee (JL, EML, EZ) and removed where identified.

From each family pedigree, information on sociodemographic characteristics, country report, number of family members at risk, and genetic ancestry were extracted. For symptomatic mutation carriers, information on clinical features (age at onset [AAO], age of death, disease duration, clinical presentation, atypical manifestations, and neurological findings) was obtained when available. We considered each symptom or sign as present or absent only if their presence or absence were clearly stated. Neuropathological and disease biomarker data were summarized when available.

3 ∣. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

One-way analysis of variance was used to test whether specific gene variants (PSEN1, PSEN2, APP) were associated with AAO. Chi-square test was used to test whether specific gene variants were associated with sex. Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare the difference in AAO between participants with PSEN1 mutations before codon 200 and those with PSEN1 mutations after codon 200. We analyzed groups of individuals with PSEN1, PSEN2, and APP mutations separately to calculate the proportion of individuals presenting with amnestic and/or atypical symptoms (eg, behavioral change, language impairment, executive impairment, motor features20,21). Proportions of patients with myoclonus; seizures; and pyramidal, extrapyramidal, or cerebellar signs were estimated for all mutation groups.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA). A P-value < .05 was considered statistically significant. This study was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.22

4 ∣. RESULTS

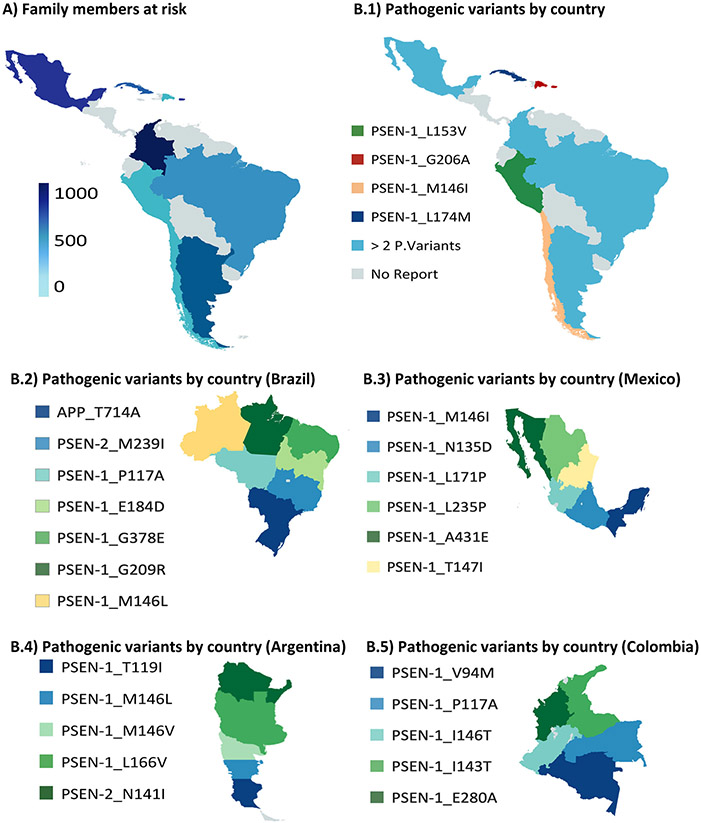

Twenty-four DIAD pathogenic variants have been reported in LatAm countries, including twenty-one PSEN1, two PSEN2, and one APP mutation. DIAD pathogenic variant reports by country are shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease in Latin American Cohorts. A, Estimated family members at risk. B.1-B.5, Pathogenic variant by countries

Our combined dataset included 3583 individuals at risk, and countries with the highest DIAD frequencies were Colombia (n = 1905),23-26 Puerto Rico (n = 672),27 Mexico (n = 463),28-30 and Cuba (n = 281),31 usually related to founder effects24,30-32 in these regions. Detailed records documenting clinical and neurological examination findings were available in 214 (54.8%) of 390 individuals with symptomatic DIAD. Estimated family members at risk by countries are summarized in Figure 2.

We found unique characteristics within the LatAm populations, including the presence of common ancestors and suggestive evidence of a high grade of admixture and ancestry background including African, Western European, Asia, and Native American (Figure 3). Furthermore, DIAD pathogenic variants were present in large extended families and following regional distribution usually related to founder effects. It’s worth noting that in certain DIAD pathogenic variants, ancestry background and/or the presence of a founder effect could not be determined due to insufficient data (Table 1).

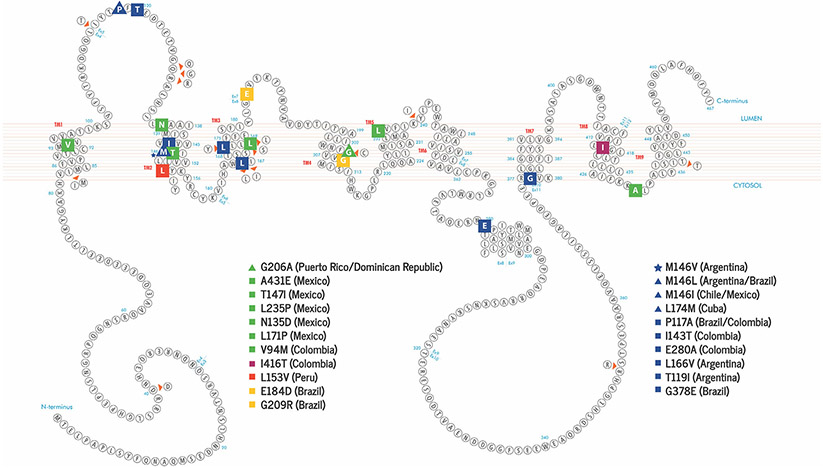

FIGURE 3.

Schematic of presenilin 1 (PSEN1) in the cell membrane and known pathogenic variants reported in Latin American (LatAm). Familial Alzheimer’s disease-linked mutations are color coded according to family ancestry background (Red = Native American, Dark Blue = Western European, Yellow = Asian, Dark Red = African, Green = Ancestry couldn’t be traced or information was not available). Variants reported in more than one LatAm country are represented using a triangle. Star shapes represent sites substitutions with more than one pathogenic variant

TABLE 1.

Summary of pathogenic variants and reported familial Alzheimer’s disease in Latin America

| Gene variant |

Exon | Type/consequence/ codon change |

LatAm country report |

Family ancestry origin |

No of families |

No of family members |

AAOa mean/range |

Predominant clinical presentation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSEN1 | ||||||||

| T119I | 5 | Point, Missense ACA to ATA | Argentina | Western European(Italy) | 1 | 27 | 57.849–71 | Amnestic |

| M146V | 5 | Point, missense ATG to GTG | Argentina | Western European(Portugal) | 1 | 23 | 36.533–40 | Amnestic/behavioral |

| M146L | 5 | Point, missense ATG to TTG | Argentina/Brazil | Western European(Italy) | 2 | 19 | 37.335–44 | Amnestic/behavioral |

| L166V | 6 | Point, missense CTT to GTT | Argentina | Western European | 1 | 14 | 4540–50 | Amnestic |

| G209R | 7 | Point, missense GTG to ATG | Brazil | Asian | 1 | 7 | 56.752–58 | Amnestic |

| G378E | 11 | Point, missense GGA to GAA | Brazil | Western European | 1 | 8 | 33.731–37 | Amnestic/behavior |

| E184D | 7 | Point, missense GAA to GAC | Brazil | Asian | 1 | 11 | 47.645–53 | Amnestic/behavior |

| P117A | 5 | Point, missense GTG to ATG | Brazil/Colombia | Western European | 2 | 6 | 34.331–37 | Amnestic/behavior |

| M146I | 5 | Point, missense ATT to ACT | Chile/Mexico | Western European | 2 | 59 | 39.337–43 | Amnestic/behavioral |

| V94M | 4 | Point, missense GAA to GCA | Colombia | No report | 2 | 23 | 53 | Amnestic |

| I143T | 5 | Point, missense ATT to ACT | Colombia | Western European | 1 | 2 | 31.530–33 | Amnestic |

| E280A | 8 | Point, missense CCA to GCA | Colombia | Western European(Spain) | 20 | 1784 | 44.334–62 | Amnestic |

| I416T | 12 | Point, missense ATG to ATC | Colombia | African | 1 | 94 | 47.438–58 | Amnestic |

| L174M | 6 | Point, missense CTG to ATG | Cuba | Western European(Spain) | 2 | 281 | 58.650–76 | Amnestic |

| G206A | 7 | Point, missense GGT to GCT | Puerto Rico/Dominican Republic | No report | 19 | 682 | 56.342–63 | Amnestic |

| L171P | 6 | Point, missense CTA to CCA | Mexico | No report | 1 | 7 | 54 | Amnestic |

| N135D | 5 | Point, missense AAT to GAT | Mexico | No report | 1 | 26 | 35.434–37 | Amnestic |

| L235P | 7 | Point, missense CTG to CCG | Mexico | No report | 1 | 20 | 37 | Amnestic |

| T147I | 5 | Point, missense ACT to ATT | Mexico | No report | 1 | 17 | 39.736–41 | Amnestic |

| A431E | 12 | Point, missense GCA to GAA | Mexico | No report | 2 | 381 | 41.233–48 | Amnestic/behavioral |

| L153V | 5 | Point, missense CTG to GTG | Peru | Amerindian or African | 1 | 16 | 35.733–38 | Amnestic |

| PSEN2 | ||||||||

| N141I | 5 | Point, missense AAC to ATC | Argentina | Western European(Germany) | 2 | 28 | 52.750–58 | Amnestic |

| M239I | 7 | Point, missense ATG to ATA | Brazil | Western European | 1 | 3 | 49.548–51 | Amnestic/behavioral |

| APP | ||||||||

| T714A | 17 | Point, missense ACA to GCA | Brazil | No report | 2 | 45 | 54.146–62 | Amnestic/behavioral |

AAO, age at onset.

Numbers included literature family reports and local researcher reports of proven families caring DIAD mutations.

Abbreviations: APP, amyloid precursor protein; DIAD: dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease; LatAm, Latin America; PSEN1, presenilin 1; PSEN2, presenilin 2.

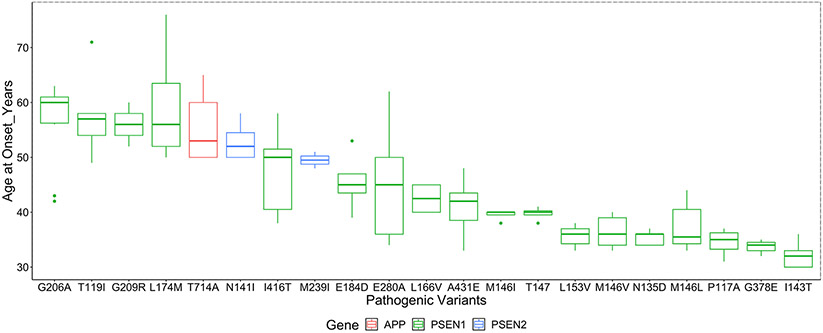

4.1 ∣. Age at onset (AAO)

Age at symptom onset was available for 203 individuals (179 with PSEN1 mutations, 11 with PSEN2 mutations and 13 with APP mutations). Mean onset was 45.3 (standard deviation [SD] ± 8.9) years for all affected patients in the combined dataset. AAO according to specific pathogenic variants are shown in Table 1. Variation in AAO was present, especially for those affected with PSEN1 mutations (Figure 4). An early onset of cognitive decline (before age 40 years) was noted in those carrying M146V,33 M146L,34,35 G378E,35 P117A,35 M146I,36 I143T,25 N135D,28 and L153V37 variants. In contrast, AAO was significantly later (after age 55 years) for individuals with T119I,38 G209R,35 L174M,31 and G206A27,39-41 variants. Participants with PSEN1 mutations before codon 200 tend to have younger AAO compared to those with PSEN1 mutations after codon 200 (median AAO 39 vs 43, P = .064).

FIGURE 4.

Mean age at onset grouped by pathogenic variant and by the affected gene.Note: To maintain participant confidentiality to mutation status family pedigrees with less than three individuals age at onset. Data points are not shown (PSEN1- L235P, PSEN1-L171P, PSEN1-V94Mwere omitted)

Mutations in PSEN2 had significantly later onset than mutations in PSEN1 and APP, and mutations in PSEN1 had significantly earlier onset than all other groups (all values significant at P < .001; Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Familial Alzheimer’s disease in Latin American cohorts

| PSEN1 | PSEN2 | APP | Total | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family pedigrees, no | 54 | 3 | 2 | 59 | – |

| Family members at risk, noa (%) | 3,507 (97.8) | 31 (0.9) | 45(1.3) | 3,583 | – |

| Affected family members, no (%) | 356 (89.3) | 14 (4.4) | 20 (6.4) | 390 | – |

| Females nob (%) | 426 (46.2) | 10 (35.7) | 18 (45.0) | 454 (45.8) | NS |

| Pathogenic variants, no | 21 | 2 | 1 | 24 | – |

| Age at onset, mean (range) | 42.4 (30–71) | 52.7(50–58) | 55.1(50–65) | – | .001c |

Family member with 50% risk of inheriting a DIAD pathogenic variant.

Not available in all the pedigrees.

P value for age at onset was based on one-way analysis of variance. P value for sex was based on Chi-square test.

Abbreviations: APP, amyloid precursor protein; DIAD: dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease; PSEN1, presenilin 1; PSEN2, presenilin 2.

4.2 ∣. Clinical and cognitive phenotypes

4.2.1 ∣. Amnestic presentations

The majority of individuals with symptomatic DIAD in our series had a single domain amnestic presentation (n = 172, 80.4%) with most of the case descriptions comprising early impairment of episodic memory, which gradually progressed to involve multiple cognitive domains. Multiple domain presentations, including amnestic plus behavior impairment, were described in kindreds featuring the PSEN1 pathogenic variants M146L,34 N135D,28 M146I,36 whereas amnestic plus language impairment was described in family members featuring PSEN1 L153V.37

4.2.2 ∣. Non-amnestic presentations

Non-amnestic presentations, including pure language, behavior, or motor presentations, were uncommon (Table 1). Progressive language decline was noted in one affected member from a kindred featuring a pathogenic variant on PSEN1 L153V.37 Behavioral presentation (“frontotemporal dementia-like”) was noted in family members (7/13, 53.8%) featuring a PSEN1 M146V pathogenic variant.33 Although a pure motor presentation was uncommon in our series, this presentation was relatively frequent (23.5%) among affected family members featuring a PSEN1 A431E29,30 pathogenic variant.

4.3 ∣. Neurological signs

4.3.1 ∣. Myoclonus and seizures

Myoclonus was noted in 30.3% of affected family members. Early myoclonus (within 3 years of symptom onset) was reported for M146I36 and A431E30 mutations. Although seizures were not identified as early manifestations in our cohort, 26.8% of affected mutation carriers, encompassing A431E,30 L153V,37 N141I,35 M146V,33 M146I36, L174M,31 I416T,24 E280A,23 and N135D28 pathogenic variants, developed seizures at later stages. Myoclonus and seizures were observed more often in very early-onset DIAD cases, particularly with a PSEN1 A431E30 mutation, where in one family, tonic-clonic seizures predated the onset of cognitive impairment. Myoclonus and seizures were absent in PSEN1 T119I,38 M146L,34 and L166V variants.

4.3.2 ∣. Extrapyramidal signs

For our review, we recorded extrapyramidal signs when the clinical description included at least one of the following: rigidity, bradykinesia, stooped posture, or shuffling gait. Extrapyramidal signs were present in 20.9% of affected family members especially in those with PSEN1 M146V,33 PSEN1 M146I,36 PSEN1 E280A,23 and PSEN1 N135D28 variants. In the majority of cases, extrapyramidal signs were not apparent until several years into the clinical course. However, early extrapyramidal syndrome was describe in two affected family members with PSEN1 M146V33 and PSEN1 M146I36 mutations. In addition, ataxia, possibly due to cerebellar rather than sensory, optic, or frontal sources, was noted in 19.0% of affected family members with PSEN1 E280A.23 In our series, no extrapyramidal signs preceded the onset of cognitive impairment; but one member of E280A family had hemiparkinsonism at the same time of amnesic onset and predating dementia diagnosis.

4.3.3 ∣. Pyramidal signs and spastic paraparesis

Pyramidal signs were described in 18.5% of affected family members. Pyramidal signs and/or spastic paraparesis were particularly frequent in kindreds featuring PSEN1 A431E30 (25.6%) and PSEN1 E280A23 (13.0%) variants. Isolated spastic paraparesis predating the onset of cognitive impairment was also described in 4 of 17 cases harboring PSEN1 A431E.30

Finally, we examined the prevalence of amnestic symptoms, non-amnestic symptoms, and neurological signs in the reported literature by gene. The number of PSEN2 and APP mutation carriers was too small to make meaningful comparisons when these covariates were considered. Within affected PSEN1 mutation carriers, no significant differences in the prevalence of parkinsonism, apraxia, visual agnosia, behavioral/personality changes, or hallucinations during the disease course were identified.

4.3.4 ∣. DIAD neuropathology and disease biomarkers in LatAm

We found relatively few reports with extensive documentation on neuropathology, biomarker profiles, and disease progression, making genotype-phenotype correlations difficult. Neuropathological reports on family members featuring DIAD pathogenic mutations were scare (12/203, 5.9%). Interestingly, in family members featuring PSEN1 M146V, the presence of AD-related neuropathology was described in association with Pick’s bodies. Of note, as mentioned above, several members of these families (7/13, 53.8%) had a behavioral presentation.33 Although small in number, DIAD pathogenic variant neuropathological reports were characterized by a high burden of amyloid plaques; numerous neurofibrillary tangles; and the absence of other meaningful co-pathologies, eg, vascular, TDP-43, or α-synuclein.28,29,31,33,39 PSEN1 E280A neuropathology and biomarker findings have been widely described relative to other DIAD pathogenic variants in LatAm.42,43

5 ∣. DISCUSSION

Despite the high number of families members with PSEN1, PSEN2, and APP pathogenic variants, there are relatively few reports from LatAm countries on the prevalence of these mutations by country. Therefore, both the number of pathogenic variants and family members featuring these mutations may be underestimated. Furthermore, we found relatively few reports with extensive documentation on the clinical phenotype, biomarker profiles, disease progression, and neuropathology from LatAm countries, making genotype-phenotype correlations difficult.8,44 Several groups have made significant efforts toward large family cohort characterization,23,45-47 but these efforts will need to be extended to other countries and regions.

In our review, we found unique characteristics within the LatAm population in contrast to what has been described in European or Asian populations featuring similar pathogenic variants. DIAD pathogenic variants in LatAm are usually present in higher frequencies, in large extended families and following a regional distribution, characteristics which can be attributable to founder effects and the presence of common ancestors. The relatively high frequency of DIAD in LatAm may reflect early colonization periods, as the establishment of nascent colonies created a reduced amount of genetic variation within the new population settlements. Moreover, previous studies have shown a high degree of inbreeding among Caribbean and South American populations, especially during colonization periods,48 which may also contribute to the existence of large families featuring mutations in the region. Other factors that contribute to the reduced genetic variation and the relatively high number of DIAD families and number of pathogenic variants are related to the complex genetic admixture of the region (European, Amerindian, and African populations).24,49,50 The unique characteristics of DIAD in LatAm may account for the high number of at-risk family members and higher prevalence of the disease relative to U.S. and European families.

Future studies will be required to determine if these features and other characteristics from LatAm populations (eg, socioeconomic status, lower educational level, admixture) may also influence more heterogeneous DIAD clinical presentations. DIAD studies including populations from LatAm, the United States, and Europe will be required to enable cross-population comparisons and answer remaining questions on disease heterogeneity across ethnic groups. In addition, we were unable to trace ancestry backgrounds or the presence of founder effects for some pathogenic mutations, suggesting the possibility for de novo mutations in LatAm populations. These hypotheses will need to be corroborated in future studies.

Regarding DIAD frequency by country, while some countries stand out for the high number of pathogenic variants and family members affected by the disease (Colombia, Mexico, Puerto Rico, Cuba), careful consideration should be taken in the context of LatAm. Health facilities in LatAm are predominantly located in large cities, with a shortage of specialists in small towns and rural areas,8 which may account for underreporting in some populations. Moreover, in most LatAm countries, dementia specialized services are mainly covered by private health insurance, with only few government-funded memory clinics or dedicated research facilities. The mentioned limitation on research funding may also explain the relatively few reports on biomarkers and neuropathology findings in DIAD population in LatAm.

The mean age at symptom onset in our LatAm cohort was 45.3 years (SD ± 8.9), which was consistent with previous reports from other cohorts outside LatAm countries.21,51-55 Although differences in age at onset were largely related to the specific DIAD mutation, we found substantial variation within many DIAD families similar to Ryman et al.,55 suggesting the possibility of gene-by-environment interactions that may play significant roles in modifying age at onset. Additionally, AAO determination is usually retrospective and thus subject to recall bias and is anticipated to be more precise with the development of longitudinal cohort studies.

Regarding clinical presentation, although some early reports emphasized that there was little phenotypic heterogeneity in familial AD cases apart from variation in AAO, it has become increasingly evident that there are differences in a minority of PSEN1 cases at the clinical, neuropsychological, neuroimaging, and neuropathological levels.20,55 In this review, we provided further evidence and detailed phenotypical characterization of affected family members from Latin America. The most frequent clinical presentation within our cohort encompasses amnestic presentations; however, significant disease heterogeneity was present between pathogenic variants and within families featuring the same pathogenic variant. Non-amnestic presentations were present in almost 20% of the individuals in our cohort, which is consistent with other cohorts worldwide.20,52 Whether these differences relate to the pathogenic variant per se, or simply reflect the heterogeneity known to occur in sporadic late-onset AD, remains an open question.

Both genetic and epigenetic factors might contribute to AAO and symptom heterogeneity. Genetic factors, including mutation site and APOE genotype, have been widely studied. Ryan et al.20 found that PSEN1 mutations before codon 200 were associated with younger age at onset, whereas mutations beyond codon 200 were more frequently associated with later ages at onset, atypical cognitive presentations, and pyramidal signs. It’s worth mentioning that the PSEN1 mutation site cut-off is typically arbitrary, and findings in regard to disease heterogeneity have not been replicated in other cohorts.21,56 Regarding APOE, previous studies have shown no influence in AAO for DIAD.20,57 The numbers of individuals with APOE genotype or other genetic data in our cohort were too small for constructing a model that includes genetic data as a covariate in addition to age of onset or clinical heterogeneity. A recent study by Arboleda-Velasquez et al. described an individual homozygous for the APOE3ch variant who was resistant to the clinical onset of DIAD.58 The effect of other genetic risk factors or risk variants will need to be validated in future cohorts.

The variability found on AAO and clinical presentation, even within families harboring the same mutation, also suggests the possibility for epigenetic and environmental factors playing a significant role. In relation to epigenetic factors, there is little to no understanding of the effect of these factors on disease heterogeneity;26,56 future studies will need to include epigenetic factors (eg, smoking, hypertension, physical activity, diet, educational level, and socioeconomic status) that might modulate changes in gene expression and therefore influence AAO, clinical presentation, and biomarker rate of change. Finally, developmental factors might also contribute to the mechanism of heterogeneity. For example, individuals that had a language learning disability as a child might be more prone to have language-led presentations related to AD.57,59

Our literature review study has limitations including the potential for reporting/publication bias of unusual or interesting cases, retrospective review of historical records, and little to no longitudinally assessed data. Most of the clinical descriptions used to characterize familial mutations in LatAm countries came from isolated case reports or small case studies, and it was not possible to ascertain whether specific manifestations were not reported because they were not present or because there was no information regarding their presence. Therefore, conclusions regarding clinical presentation, AAO, disease duration, or the presence of atypical clinical features will need to be assessed in future cohorts. Similarly, we had little to no information on AD biomarker data from LatAm families, and future studies will be needed to better understand AD biomarker rate of change within this cohort and establish comparisons to Asian, North American, and Western European cohorts in DIAN. In addition, a better understanding of gene-by-environment interactions on AAO and disease progression will be needed to inform prognosis of future rates of decline and potential therapeutic approaches. Finally, although we have described a relatively high frequency of DIAD mutations in Latin America, these numbers may be underestimated. It’s worth noting that potential sample bias related to differences in health-care access and system level resources in LatAm countries may account for the lack of DIAD reports in some LatAm countries (eg, El Salvador) or the disproportionally higher number in other LatAm countries (eg, Colombia). In addition, research funding varies significantly from country to country, which may explain differences in case identification and reports. Future studies will need to expand on genetic testing in LatAm and test disease pathogenicity on variants of unknown/uncertain significance.

Despite these limitations, our literature review was enriched by updates and contributions from local researchers who follow these families, and to the best of our knowledge, we have performed the most comprehensive review of DIAD mutations in LaAm, leading the way for characterization of these families in future studies. Regional efforts are under way to extend the DIAN observational studies to LatAm to better understand the pathophysiology of AD through cerebrospinal fluid and blood biomarkers, brain tau, and Aβ deposition (using positron emission tomography) and structural (magnetic resonance) imaging combined with demographic, environmental, cognitive, clinical, and functional changes in DIAD. The DIAN-LatAm centers in Argentina (Buenos Aires/Salta), Colombia (Medellin), Mexico (Mexico City and Guadalajara), and Brazil (São Paulo) will start recruitment and enrollment by the end of 2020/early 2021, and DIAD families members will have the possibility to join the observational studies or the DIAN-TU primary and secondary prevention trials. Furthermore, in partnership with the DIAN EXR and local researchers (DIAN-LatAm liaisons), a new collaboration platform has been developed to facilitate genetic counseling and testing and to explore DIAD pathogenicity in LatAm families featuring variants of unknown/uncertain significance. Future studies will include cross-country comparisons and early identification and characterization of DIAD families, which together will facilitate future prevention trials as pharmacological interventions emerge.

Supplementary Material

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

Systematic review: The authors reviewed the literature using traditional (eg, PubMed) sources, meeting abstracts, and presentations. While a growing number of dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease (DIAD) cases have become known in Latin America (LatAm) in recent years, little is known about mutation frequency by country, number of family members, and clinical phenotype of pathogenic variants in LatAm countries.

Interpretation: Our findings confirmed a relative high frequency of DIAD in LatAm. We found unique characteristics within the LatAm populations, including the presence of common ancestors and large extended families usually related to founder effects.

Future directions: Future DIAD studies will be required in LatAm, albeit with a more systematic approach to include fluid biomarker and imaging studies. Regional efforts are under way to extend the DIAN observational studies to Latin America to better understand the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease through cerebrospinal fluid, imaging, and blood biomarkers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN, U19AG032438) funded by the National Institute on Aging (NIA), Alzheimer’s Association (SG-20-690363), the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE), The Institute for Neurological Research (FLENI), and CONICET (PICT 2015/2110), partial support by the Research and Development Grants for Dementia from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, AMED, and the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI). This article has been reviewed by DIAN Study investigators for scientific content and consistency of data interpretation with previous DIAN Study publications. We acknowledge the altruism of the participants and their families and the DIAN research and support staff at each of the participating sites for their contributions to this study.

Funding Information

Data collection and sharing for this project was supported by The Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN, UF1AG032438) funded by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and Alzheimer’s Association (SG-20-690363). This article has been reviewed by DIAN Study investigators for scientific content and consistency of data interpretation with previous DIAN Study publications. The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The corresponding author had full access to the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no disclosures relevant to this manuscript.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.2019 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement 2019;15: 321–387. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reitz C, Brayne C, Mayeux R. Epidemiology of Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011; 7: 137–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, Wimo A, Ribeiro W, Ferri CP. The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2013; 9: 63–75.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prince M, Acosta D, Ferri CP,et al. Dementia incidence and mortality in middle-income countries, and associations with indicators of cognitive reserve: a 10/66 Dementia Research Group population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2012; 380: 50–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prince M, Acosta D, Albanese E, et al. Ageing and dementia in low and middle income countries-Using research to engage with public and policy makers. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2008; 20: 332–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez JJL, Ferri CP, Acosta D,et al. Prevalence of dementia in Latin America, India, and China: a population-based cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2008; 372: 464–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nitrini R, Bottino CMC, Albala C, et al. Prevalence of dementia in Latin America: a collaborative study of population-based cohorts. Int Psychogeriatrics. 2009; 21: 622–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parra MA, Baez S, Allegri R, et al. Dementia in Latin America Assessing the present and envisioning the future. Neurology. 2018; 90: 222–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017; 390: 2673–734. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Benzinger TLS, et al. Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2012; 367: 795–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bateman RJ, Aisen PS, De Strooper B, et al. Autosomal-dominant Alzheimer’s disease: a review and proposal for the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2010; 3: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldman JS, Hahn SE, Catania JW, et al. Genetic counseling and testing for Alzheimer disease: joint practice guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and the National Society of Genetic Counselors. Genet Med. 2011; 13: 597–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gooding HC, Linnenbringer EL, Burack J, Roberts JS, Green RC, Biesecker BB. Genetic susceptibility testing for Alzheimer disease: motivation to obtain information and control as precursors to coping with increased risk. Patient Educ Couns. 2006; 64: 259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atkins ER, Panegyres PK. The clinical utility of gene testing for Alzheimer’s disease. Neurol Int. 2011; 3: e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bateman RJ, Benzinger TL, Berry S, et al. The DIAN-TU Next Generation Alzheimer’s prevention trial: adaptive design and disease progression model. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2017; 13(1): 8–19. 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moulder KL, Snider BJ, Mills SL, et al. Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network: facilitating research and clinical trials. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2013; 5: 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cummings J, Reiber C, Kumar P. The price of progress: funding and financing Alzheimer’s disease drug development. Alzheimer’s Dement (New York, N Y). 2018; 4: 330–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cruts M, Theuns J, Van Broeckhoven C. Locus-specific mutation databases for neurodegenerative brain diseases. Hum Mutat. 2012; 33: 1340–1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bertram L, McQueen MB, Mullin K, Blacker D, Tanzi RE. Systematic meta-analyses of Alzheimer disease genetic association studies: the AlzGene database. Nat Genet. 2017; 39(1): 17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryan NS, Nicholas JM, Weston PSJ, et al. Clinical phenotype and genetic associations in autosomal dominant familial Alzheimer’s disease: a case series. Lancet Neurol. 2016; 15: 1326–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang M, Ryman DC, McDade E, et al. Neurological manifestations of autosomal dominant familial Alzheimer’s disease: a comparison of the published literature with the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network observational study (DIAN-OBS). Lancet Neurol. 2016; 15: 1317–1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009; 339: 332–336. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopera F, Ardilla A, Martínez A, et al. Clinical features of early-onset Alzheimer disease in a large kindred with an E280A presenilin-1 mutation. J Am Med Assoc. 1997; 277: 793–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramirez Aguilar L, Acosta-Uribe J, Giraldo MM, et al. Genetic origin of a large family with a novel PSEN1 mutation (Ile416Thr). Alzheimer’s Dement. 2019; 15: 709–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arango D, Cruts M, Torres O, et al. Systematic genetic study of Alzheimer disease in Latin America: mutation frequencies of the amyloid β precursor protein and presenilin genes in Colombia. Am J Med Genet. 2001; 103: 138–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aguirre-Acevedo DC, Lopera F, Henao E, et al. Cognitive Decline in a Colombian Kindred With Autosomal Dominant Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurol. 2016; 73: 431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee JH, Kahn A, Cheng R, et al. Disease-related mutations among caribbean hispanics with familial dementia. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2014; 2: 430–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crook R, Ellis R, Shanks M, et al. Early-onset Alzheimer’s disease with a presenilin-1 mutation at the site corresponding to the Volga German presenilin-2 mutation. Ann Neurol. 1997; 42: 124–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murrell J, Ghetti B, Cochran E, et al. The A431E mutation in PSEN1 causing Familial Alzheimer’s Disease originating in Jalisco State, Mexico: an additional fifteen families. Neurogenetics. 2006; 7: 277–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yescas P, Huertas-Vazquez A, Villarreal-Molina MT, et al. Founder effect for the Ala431Glu mutation of the presenilin 1 gene causing early-onset Alzheimer’s disease in Mexican families. Neurogenetics. 2006; 7: 195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bertoli Avella AM, Marcheco Teruel B, Llibre Rodriguez JJ, et al. A novel presenilin 1 mutation (L174 M) in a large Cuban family with early onset Alzheimer disease. Neurogenetics. 2002; 4: 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lalli MA, Cox HC, Arcila ML, et al. Origin of the PSEN1 E280A mutation causing early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement 2014; 10(55): S277–S283.e10. 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riudavets MA, Bartoloni L, Troncoso JC, et al. Familial Dementia With Frontotemporal Features Associated With M146V Presenilin-1 Mutation. Brain Pathol. 2013; 23: 595–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morelli L, Prat MI, Levy E, Mangone CA, Castaño EM. Presenilin 1 Met146Leu variant due to an A&T transversion in an early-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease pedigree from Argentina. Clin Genet. 2008; 53: 469–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takada LT, Dozzi Brucki SM, Rodriguez RD, et al. Autosomal dominant early-onset alzheimer’s disease: characterization of a brazilian cohort. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2017; 13: P968. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sinning M, Van Rooyen JP, Venegas-Francke P, Vásquez C, Behrens MI, Ramírez A. Clinical and genetic analysis of a chilean family with early-onset autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2010; 21: 757–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cornejo-Olivas MR, Yu CE, Mazzetti P, et al. Clinical and molecular studies reveal a PSEN1 mutation (L153V) in a Peruvian family with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2014; 563: 140–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Itzcovich T, Chrem-Méndez P, Vázquez S, et al. A novel mutation in PSEN1 (p.T119I)in an Argentine family with early- and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arnold SE, Vega IE, Karlawish JH,et al. Frequency and clinicopathological characteristics of presenilin 1 Gly206Ala mutation in puertorican hispanics with dementia. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2013; 33: 1089–1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Athan ES, Williamson J, Ciappa A, et al. A founder mutation in presenilin 1 causing early-onset Alzheimer disease in unrelated Caribbean Hispanic families. J Am Med Assoc. 2001; 286: 2257–2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ravenscroft TA, Pottier C, Murray ME, et al. The presenilin 1 p.Gly206Ala mutation is a frequent cause of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease in Hispanics in Florida. Am J Neurodegener Dis. 2016; 5: 94–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reiman EM, Quiroz YT, Fleisher AS, et al. Brain imaging and fluid biomarker analysis in young adults at genetic risk for autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease in the presenilin 1 E280A kindred: a case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 2012; 11: 1048–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fuller JT, Cronin-Golomb A, Gatchel JR, et al. Biological and cognitive markers of presenilin1 E280A Autosomal Dominant Alzheimer’s disease: a comprehensive review of the Colombian Kindred. J Prev Alzheimer’s Dis. 2019; 6: 112–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gonzalez FJ, Gaona C, Quintero M, Chavez CA, Selga J, Maestre GE. Building capacity for dementia care in Latin America and the Caribbean. Dement Neuropsychol. 2014; 8: 310–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sepulveda-Falla D, Glatzel M, Lopera F. Phenotypic profile of early-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease caused by presenilin-1 E280A mutation. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2012; 32: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quiroz YT, Sperling RA, Norton DJ, et al. Association between amyloid and tau accumulation in young adults with autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease. JAMA Neurol. 2018; 75: 548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tariot PN, Lopera F, Langbaum JB, et al. The Alzheimer’s Prevention Initiative Autosomal-Dominant Alzheimer’s Disease Trial: A study of crenezumab versus placebo in preclinical PSEN1 E280A mutation carriers to evaluate efficacy and safety in the treatment of autosomal-dominant Alzheimer’s disease, including a placebo-treated noncarrier cohort. Dement Transl Res Clin Interv. 2018; 4: 150–160. 10.1016/j.trci.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vardarajan BN, Schaid DJ, Reitz C, et al. Inbreeding among Caribbean Hispanics from the Dominican Republic and its effects on risk of Alzheimer disease. Genet Med. 2015; 17: 639–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Homburger JR, Moreno-Estrada A, Gignoux CR, et al. Genomic Insights into the Ancestry and Demographic History of South America. PLoS Genet. 2015; 11: e1005602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ruiz-Linares A, Adhikari K, Acuña-Alonzo V, et al. Admixture in Latin America: geographic Structure, Phenotypic Diversity and Self-Perception of Ancestry Based on 7,342 Individuals. PLoS Genet. 2014; 10(9): e1004572. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ryan NS, Rossor MN. Correlating familial Alzheimers disease gene mutations with clinical phenotype. Biomark Med. 2010; 4: 99–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shea YF, Chu LW, Chan AOK, Ha J, Li Y, Song YQ. A systematic review of familial Alzheimer’s disease: differences in presentation of clinical features among three mutated genes and potential ethnic differences. J Formos Med Assoc. 2016; 115: 67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Campion D, Dumanchin C, Hannequin D, et al. Early-onset autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease: prevalence, genetic heterogeneity, and mutation spectrum. Am J Hum Genet. 1999; 65: 664–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bruni AC, Bernardi L, Colao R, et al. Worldwide distribution of PSEN1 Met146Leu mutation: a large variability for a founder mutation. Neurology. 2010; 74: 798–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ryman DC, Aisen PS, Bird T, et al. Symptom onset in autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology 2014;83(3):253–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Larner AJ, Doran M. Clinical phenotypic heterogeneity of Alzheimer’s disease associated with mutations of the presenilin-1 gene. J Neurol. 2006; 253: 139–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Van der Flier WM. Clinical heterogeneity in familial Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2016; 15(13): 1296–1298. 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30275-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arboleda-Velasquez JF, Lopera F, O’Hare M, et al. Resistance to autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease in an APOE3 Christchurch homozygote: a case report. Nat Med. 2019; 25(11): 1680–1683. 10.1038/s41591-019-0611-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miller ZA, Mandelli ML, Rankin KP, et al. Handedness and language learning disability differentially distribute in progressive aphasia variants. Brain, 2013; 136(11): 3461–3473. 10.1093/brain/awt242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.