Abstract

BACKGROUND

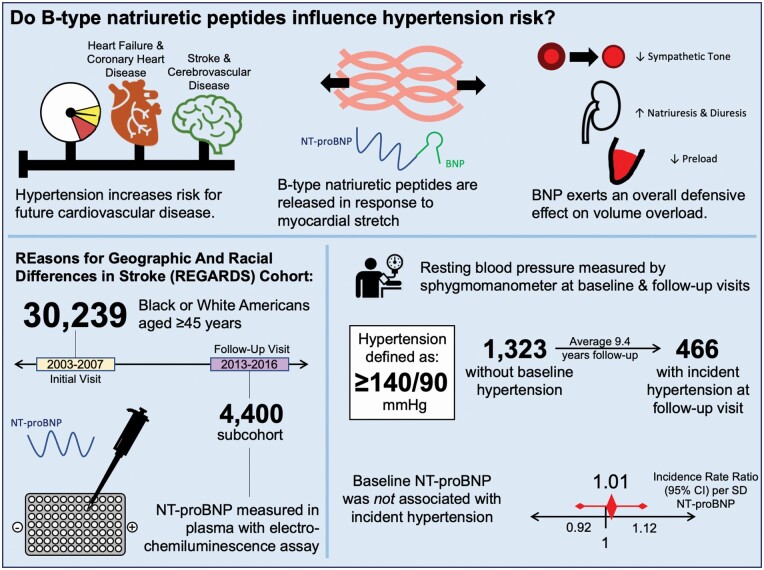

Hypertension is a common condition that increases risk for future cardiovascular disease. N-terminal B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) is higher in individuals with hypertension, but studies of its association with hypertension risk have been mixed.

METHODS

The REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study enrolled 30,239 U.S. Black or White adults aged ≥45 years from 2003 to 2007. A subcohort included 4,400 participants who completed a second assessment in 2013–2016. NT-proBNP was measured by immunoassay in 1,323 participants without baseline hypertension, defined as blood pressure ≥140/90 or self-reported antihypertensive prescriptions. Two robust Poisson regression models assessed hypertension risk, yielding incidence rate ratios (IRRs): Model 1 included behavioral and demographic covariates and Model 2 added risk factors. A sensitivity analysis using a less conservative definition of hypertension (blood pressure ≥130/80 or self-reported antihypertensive prescriptions) was conducted.

RESULTS

Four hundred and sixty-six participants developed hypertension after mean follow-up of 9.4 years. NT-proBNP was not associated with hypertension (Model 2 IRR per SD log NT-proBNP 1.01, 95% confidence interval 0.92–1.12), with no differences by sex, body mass index, age, or race. Similar findings were seen in lower-threshold sensitivity analysis.

CONCLUSIONS

NT-proBNP was not associated with incident hypertension in REGARDS; this did not differ by race or sex.

Keywords: blood pressure, B-type natriuretic peptide, cohort studies, hypertension, natriuretic peptides

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Hypertension is a common condition that increases risk for other disease processes, including coronary artery disease, stroke, and renal disease.1 While certain traits predispose to hypertension2 in addition to distinct etiologies, biomarkers have not been applied to the stratification of hypertension risk. B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) is a 32-residue peptide released by distended cardiomyocytes in states of pressure or volume overload.3 A clinical marker of ventricular dysfunction in heart failure, BNP promotes vasodilation, blood pressure-independent natriuresis and diuresis, and decreased preload and sympathetic tone.4 Thus, BNP has a generally defensive effect against volume overload, promoting reduction of blood pressure in response to myocardial stretch. Transgenic mice overexpressing BNP have lower systolic blood pressure than wild-type littermates.5

Given these preclinical findings, BNP-related biomarkers might identify those at high risk for developing hypertension. However, investigations of the association between BNP-related biomarkers and hypertension have had inconsistent findings.6–9 As BNP is unstable in vitro, many clinical investigations of BNP in humans measure the stable cleavage fragment of the BNP precursor molecule, amino-terminal-pro-BNP (NT-proBNP).10 With a large cohort study of Black and White participants, we investigated associations of NT-proBNP with incident hypertension and differences in this association by sex, race, age, and body mass index (BMI) groups.

METHODS

Sample

The REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study is a contemporary cohort study that enrolled 30,239 non-Hispanic Black and White American participants aged ≥45 years between 2003 and 2007. Details were previously published.11 The REGARDS study and this investigation have been approved by the institutional review boards of all participating institutions.

Potential participants were randomly selected from a commercially available list and contacted for enrollment by telephone and mail. An initial telephone interview obtained medical history and verbal consent. Immediate exclusion criteria were: apparent cognitive impairment during interview, active treatment of malignancy, medical conditions prohibiting long-term follow-up, waitlisting for or residence in a nursing facility, or inability to communicate proficiently in English. An assessment in each participant’s home was then conducted, during which a medication inventory, electrocardiogram, biometrics, fasting phlebotomy, urine samples, and written consent were obtained. Blood pressure was measured over the brachial artery via aneroid sphygmomanometer by a trained examiner following a standardized protocol. Participants were seated at rest for at least 5 minutes prior to measurement. Blood pressure was reported in millimeters of mercury (mm Hg) and assessed as the mean systolic and mean diastolic components of 2 separate measurements taken 5 minutes apart. Beginning in 2013, all participants are being invited to undergo a similar second telephone and in-home evaluation, including examiner measurement of blood pressure, approximately 10 years after their initial in-home visit.12 Additional verbal and written consent was obtained for this second visit.

Of the 13,912 participants who completed the second in-home visit from 2013 to 2016, 4,400 were selected for a subcohort by stratified random sampling with equal allocation across race and sex, a strategy which minimized bias and preserved Type I error in statistical simulations. This raw sample included 617 participants who were free of hypertension at baseline but developed hypertension (defined below) by the second evaluation. Participants were excluded from analysis based on criteria shown in Figure 1. Participants with NT-proBNP >100 pg/ml13 were excluded to minimize the impact of subclinical cardiovascular disease on the outcome.

Figure 1.

Exclusion criteria. Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; REGARDS, REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke.

Variables

Demographic and lifestyle variables included age, sex, race, education level (<high school, high school graduate, some college, or ≥college), region (Stroke Belt, Stroke Buckle,14 or other), exercise level (none, 1–3 times weekly, ≥4 times weekly), alcohol intake (none, moderate [1–7 drinks per week for women, 1–14 drinks per week for men], or heavy [>7 drinks per week in women, >14 drinks per week in men]), and tobacco use (pack-years or current status [never smoker, past smoker, current smoker]).

Baseline clinical variables included history of diabetes mellitus (self-reported use of hypoglycemic drugs or insulin, random glucose ≥200 mg/dl, or fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dl) and left ventricular hypertrophy (electrocardiogram finding defined using Sokolow–Lyon criteria15). Heart failure was identified in individuals reporting orthopnea or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. BMI was calculated using height and weight at baseline. Estimated glomerular filtration rate was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation16; an estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 signified renal dysfunction. The 4-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CESD-4)17 was used to quantify depressive symptomology over the week prior to telephone interview. Scores ranged from 0 to 12, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms, and were considered continuously in regression models.

The Block 98 Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ)18 estimated each participant’s typical dietary intake over the preceding year. Adherence to 3 dietary patterns was assessed by considering the intake of various food groups more and less typical of each pattern. Adherence to the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet was calculated as previously documented; 19 a score <25th percentile (21 in this sample) were considered low adherence. Mediterranean diet scores ranged from 0 to 9, with higher score indicative of stronger adherence, and were dichotomized into low (0–4) and high (5–9) adherence categories.20 DASH and Mediterranean diet scores were considered in their low–high adherence dichotomies for cross-sectional analyses and continuously when included in regression. A novel factor analysis of 56 food groups was used to further categorize dietary patterns in REGARDS.21 A factor group with heavy intake of fried food, processed meats, added fats, and sweetened beverages similar to dietary patterns characteristic of the Southern United States, was deemed a “Southern Diet” pattern.

Hypertension was defined by systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg, or self-reported use of antihypertensive medications, according to the Guidelines of the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure.22 A planned sensitivity analysis defined hypertension according to the 2017 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults23: self-reported use of antihypertensive medications, measured systolic blood pressure ≥130 mm Hg, or diastolic blood pressure ≥80 mm Hg. Incident hypertension was identified in those not meeting criteria at the initial in-home visit but meeting criteria at the second in-home visit.

Laboratory variables

Fasting blood samples were obtained from each participant at the initial visit. Samples were locally centrifuged then shipped on ice to the core laboratory at the University of Vermont. They were centrifuged again at 30,000g and aliquoted and stored at −80 °C. Colorimetric reflectance spectrophotometry measured blood glucose (Ortho Vitros 950 IRC Clinical Analyzer, Johnson & Johnson Clinical Diagnostics). Serum creatinine was measured with isotope dilution mass spectrometry-traceable methods.

NT-proBNP was measured using EDTA plasma in the subcohort. Thawed plasma was run on an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Roche Cobas e411 Special Chemistry Analyzer, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), which had a detectable range of 5–35,000 pg/ml, and interassay coefficient of variation <5%. NT-proBNP was common logarithm-transformed for analyses in which it was to be considered continuously or quartiled for other analyses.

Statistical analysis

Probability weighting was used to account for the sampling technique employed in the subcohort, stratified on race and sex and using a Taylor series as a finite population correction. Participants missing values were excluded from analyses for which values were absent. Baseline characteristics of the subcohort were compared across quartiles of NT-proBNP using Pearson chi-squared tests with a second-order transformation according to Rao and Scott24 (categorical variables) or one-way analysis of variance (continuous variables). Statistical testing was two-sided with α = 0.05 and performed with Stata version 16.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Two weighted Poisson regression models with robust standard error estimation were fitted to examine the association of plasma NT-proBNP with incidence of hypertension. Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) per SD, or quartiles vs. quartile 4 were reported. Model 1 included demographic and behavioral covariates: age, sex, race, income, education, alcohol use, tobacco use (pack-years), and CESD-4 score. Model 2 added hypertension risk factors25 to Model 1: resting heart rate, diabetes mellitus, BMI, estimated glomerular filtration rate, left ventricular hypertrophy, and continuous diet scores (DASH, Mediterranean, Southern). Multiplicative interaction terms were added to each model for log NT-proBNP and sex, race, BMI, and age. Model 1 was graphically presented using a cubic restricted spline and 95% confidence interval with knots specified according to Harrell’s method26 and referencing median values of log NT-proBNP. Distributions of log NT-proBNP were presented using kernel density plots.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

One thousand three hundred and twenty-three participants were included in analysis following the exclusion criteria shown in Figure 1, including 466 participants with incident hypertension and 857 who remained hypertension-free. Mean follow-up time was 9.4 years (SD 1.0 years). Median [IQR] NT-proBNP was 35 [17, 59] pg/ml and ranged from 5 to 100 pg/ml.

Mean systolic blood pressure was 119 mm Hg (SD 11 mm Hg) at baseline and 121 mm Hg (SD 13 mm Hg) at follow-up. Mean diastolic blood pressure was 74 mm Hg (SD 7 mm Hg) at baseline and 73 mm Hg (SD 8 mm Hg) at follow-up.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1 and compared across quartiles of NT-proBNP in Table 2. Participants in lower quartiles of NT-proBNP were younger and had higher BMI, estimated glomerular filtration rate, Southern diet score, and resting heart rate, with larger proportions of men, and Black participants (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of included participants

| Log NT-proBNP (pg/ml; mean [SD]) | 3.4 (0.9) |

| Age (years; mean [SD]) | 60.4 (7.9) |

| Black race (%) | 38.4 |

| Male sex (%) | 53.1 |

| Region (%) | |

| Stroke Belt | 32.4 |

| Stroke Buckle | 20 |

| Other | 47.5 |

| Annual income (%) | |

| <$20,000 | 8.8 |

| $20,000–$34,999 | 18.1 |

| $35,000–$74,000 | 34.5 |

| ≥$75,000 | 28.2 |

| Refused | 10.4 |

| Education (%) | |

| <High school | 4.9 |

| High school grad | 19.7 |

| Some college | 26.9 |

| ≥College | 48.5 |

| Weekly exercise (%) | |

| None | 25.5 |

| 1–3 times | 41.8 |

| ≥4 times | 32.8 |

| Tobacco use (%) | |

| Never smoker | 51.5 |

| Past smoker | 37.9 |

| Current smoker | 10.6 |

| Current alcohol use (%) | |

| None | 52.6 |

| Moderate | 42.7 |

| Heavy | 4.7 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg; mean [SD]) | 119 (11) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg; mean [SD]) | 74 (7) |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 1.4 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2; mean [SD]) | 27.7 (5.1) |

| Resting heart rate (bpm; mean [SD]) | 65 (10) |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2; mean [SD]) | 93 (14) |

| Southern diet score (mean [SD]) | −0.13 (1.02) |

| Low Mediterranean diet adherence (%) | 38.8 |

| Low DASH diet adherence (%) | 16 |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy (%) | 5.3 |

Abbreviations: bpm, beats per minute; DASH, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; mmHg, millimeters of mercury; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of included participants by NT-proBNP quartilea

| NT-proBNP quartiles | Q1 (5–16 pg/ml) | Q2 (17–34 pg/ml) | Q3 (35–58 pg/ml) | Q4 (59–100 pg/ml) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years; mean, 95% CI) | 58.6 (57.8, 59.4) | 59.0 (58.2, 59.7) | 61.2 (60.4, 62.0) | 62.9 (61.9, 63.8) | <0.001b |

| Black race (%) | 40.9 | 29.8 | 20.6 | 17.1 | <0.001c |

| Male sex (%) | 65.4 | 51.2 | 42.8 | 38.0 | <0.001c |

| Region (%) | |||||

| Stroke Belt | 32.9 | 26.5 | 35.7 | 35.8 | 0.13c |

| Stroke Buckle | 18.6 | 19.9 | 20.0 | 20.5 | |

| Other | 48.5 | 53.6 | 44.2 | 43.7 | |

| Annual income (%) | |||||

| <$20,000 | 9.9 | 6.4 | 7.7 | 8.6 | 0.29c |

| $20,000–$34,999 | 18.3 | 14.8 | 18.3 | 18.8 | |

| $35,000–$74,000 | 28.6 | 35.6 | 36.5 | 33.4 | |

| ≥$75,000 | 33.3 | 33.4 | 25.6 | 26.9 | |

| Refused | 9.9 | 9.8 | 12.1 | 12.2 | |

| Education (%) | |||||

| <High school | 5.8 | 4.2 | 2.1 | 5.4 | 0.3c |

| High school grad | 19.5 | 16.8 | 20.6 | 17.3 | |

| Some college | 24.4 | 25.7 | 29.5 | 25.9 | |

| ≥College | 50.4 | 53.4 | 47.8 | 51.5 | |

| Weekly exercise (%) | |||||

| None | 28.6 | 24.5 | 24.1 | 23.7 | 0.16c |

| 1–3 times | 38.9 | 39.9 | 39.7 | 47.8 | |

| ≥4 times | 32.5 | 35.7 | 36.2 | 28.5 | |

| Tobacco use (%) | |||||

| Never smoker | 48.8 | 54.1 | 53.7 | 52.2 | 0.85c |

| Past smoker | 41.2 | 35.8 | 37.4 | 38.9 | |

| Current smoker | 10.0 | 10.1 | 9.0 | 8.8 | |

| Current alcohol use (%) | |||||

| None | 50.0 | 51.3 | 53.4 | 49.4 | 0.87c |

| Moderate | 45.0 | 43.1 | 42.8 | 44.9 | |

| Heavy | 5.0 | 5.7 | 3.7 | 5.7 | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg; mean, 95% CI) | 119 (118, 120) | 118 (116, 119) | 118 (117, 120) | 119 (118, 120) | 0.78b |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg; mean, 95% CI) | 76 (75, 76) | 74 (73, 75) | 74 (73, 75) | 73 (72, 74) | <0.001b |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 1.4 | 2.3 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.15c |

| Body mass index (kg/m2; mean, 95% CI) |

28.4 (28.0, 29.1) | 27.8 (27.3, 28.4) | 27.1 (26.5, 27.6) | 27.0 (26.5, 27.6) | <0.001b |

| Resting heart rate (bpm; mean, 95% CI) | 66.1 (64.9, 67.3) | 65.4 (64.3, 66.5) | 64.8 (63.7, 65.9) | 64.1 (63.0, 65.1) | 0.01b |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2; mean, 95% CI) | 95 (94, 97) | 93 (92, 95) | 91 (90, 92) | 90 (89, 91) | <0.001b |

| Southern diet score (mean, 95% CI) | −0.10 (−0.22, 0.02) | −0.20 (−0.32, −0.08) | −0.25 (−0.36, −0.13) | −0.37 (−0.47, −0.27) | 0.001b |

| Low Mediterranean diet adherence (%) | 40.7 | 37.8 | 44.8 | 39.6 | 0.32c |

| Low DASH diet adherence (%) | 15.8 | 15.9 | 18.7 | 13.5 | 0.35c |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy (%) | 6.5 | 3.4 | 5.9 | 3.8 | 0.19c |

Abbreviations: bpm, beats per minute; CI, confidence interval; DASH, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; mmHg, millimeters of mercury; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide.

aWeighted to analytical cohort

bOne-way analysis of variance.

cRao–Scott χ 2.

Association of NT-proBNP with incident hypertension

Table 3 shows IRRs for hypertension by log-transformed and quartiled NT-proBNP overall and stratified by sex and race groups. Log-transformed or quartiled NT-proBNP were not associated with incident hypertension overall in Model 1 (IRR per SD log NT-proBNP 1.00, 95% confidence interval 0.91–1.09) or Model 2 (IRR per SD log NT-proBNP 1.01, 95% confidence interval 0.92–1.12). Figure 2 depicts the association of log NT-proBNP with incident hypertension in Model 1 using cubic restricted splines.

Table 3.

NT-proBNP and incidence rate ratios (95% CI) of incident hypertension overall, by sex, and by race

| Per SD log NT-proBNP | Quartiles | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (5–16 pg/ml) | Q2 (17–34 pg/ml) | Q3 (35–58 pg/ml) | Q4 (59–100 pg/ml) | P for trend | ||

| Overall | ||||||

| n incident HTN/n at risk | 466/1,323 | 125/330 | 106/331 | 118/331 | 117/331 | |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (0.91, 1.09) | 1.06 (0.84, 1.34) | 0.84 (0.66, 1.07) | 1.02 (0.82, 1.27) | 1 (ref) | 0.97 |

| Model 2 | 1.01 (0.92, 1.12) | 1.04 (0.80, 1.34) | 0.81 (0.62, 1.07) | 1.01 (0.79, 1.28) | 1 (ref) | 0.80 |

| Women | ||||||

| n incident HTN/n at risk | 214/621 | 41/97 | 45/150 | 59/177 | 69/197 | |

| Model 1 | 1.02 (0.89, 1.18) | 1.12 (0.80, 1.57) | 0.75 (0.54, 1.05) | 0.93 (0.70, 1.25) | 1 (ref) | 0.90 |

| Model 2 | 1.01 (0.86, 1.19) | 1.16 (0.78, 1.71) | 0.75 (0.51, 1.10) | 0.94 (0.67, 1.30) | 1 (ref) | 0.94 |

| Men | ||||||

| n incident HTN/n at risk | 252/702 | 84/233 | 61/181 | 59/154 | 48/134 | |

| Model 1 | 0.98 (0.88, 1.10) | 1.14 (0.81, 1.59) | 1.00 (0.70, 1.45) | 1.26 (0.90, 1.78) | 1 (ref) | 0.80 |

| Model 2 | 1.04 (0.91, 1.18) | 0.95 (0.65, 1.39) | 0.94 (0.62, 1.41) | 1.15 (0.79, 1.66) | 1 (ref) | 0.54 |

| Black | ||||||

| n incident HTN/n at risk | 218/508 | 75/187 | 60/138 | 42/101 | 41/82 | |

| Model 1 | 1.05 (0.94, 1.17) | 0.85 (0.63, 1.17) | 0.81 (0.59, 1.11) | 0.85 (0.61, 1.19) | 1 (ref) | 0.37 |

| Model 2 | 1.02 (0.89, 1.18) | 0.89 (0.62, 1.28) | 0.72 (0.48, 1.08) | 0.81 (0.55, 1.21) | 1 (ref) | 0.63 |

| White | ||||||

| n incident HTN/n at risk | 248/815 | 50/143 | 46/193 | 76/230 | 76/249 | |

| Model 1 | 0.97 (0.86, 1.10) | 1.19 (0.87, 1.63) | 0.80 (0.57, 1.12) | 1.08 (0.82, 1.42) | 1 (ref) | 0.75 |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (0.88, 1.14) | 1.07 (0.77, 1.48) | 0.77 (0.54, 1.08) | 1.03 (0.78, 1.37) | 1 (ref) | 0.79 |

Covariates in multivariable models: Model 1: age, sex, race, income, education, alcohol use, CESD score, and tobacco smoking (pack-years). Model 2: Model 1 covariates and resting heart rate, baseline diabetes, baseline BMI, baseline eGFR, Southern diet score, and Mediterranean diet score. Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CESD, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression; CI, confidence interval; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HTN, hypertension; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide.

Figure 2.

Incidence rate ratio (IRR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) (shaded) for risk of incident hypertension across log NT-proBNP, depicted using a restricted cubic spline, with knots specified by Harrell’s method and set at 1.6, 3.5, 4.3, and 5.8 pg/ml, referencing median log NT-proBNP (3.6 pg/mL), and adjusted for other Model 1 covariates (age, sex, income, education, alcohol use, smoking (pack-years), and CESD-4 score). The spline functions were cut short at the 0.5th and 99.5th percentiles of log NT-proBNP. Kernel density plots show distributions of log NT-proBNP, stratified by participants with and without incident hypertension. Abbreviations: CESD-4, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale; HTN, hypertension; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide.

Sex did not significantly interact with log NT-proBNP (Model 2 interaction P = 0.82), nor did race (Model 2 interaction P = 0.39), age (Model 2 interaction P = 0.80), or BMI (Model 2 interaction P = 0.69). Log-transformed or quartiled NT-proBNP were not associated with incident hypertension in any age or BMI group (stratified results not shown).

Sensitivity analysis

Findings from the sensitivity analysis incorporating 2017 AHA/ACC guidelines did not differ materially from the main findings and are shown in Supplementary Table S1 online. No interactions of race, sex, age, or BMI were observed in the sensitivity analysis (all Model 2 interaction P > 0.12).

Discussion

In this biracial contemporary study of American adults free of hypertension at baseline, baseline NT-proBNP was not associated with risk of hypertension after an average of 9.4 years of follow-up. In previous cross-sectional studies, NT-proBNP was higher in individuals with hypertension.6,7 Prospective studies examining the association of natriuretic peptides with risk of hypertension yielded mixed results, indicating that higher NT-proBNP increased overall risk for hypertension8 and BNP increased risk of blood pressure progression in men.9 A previous investigation within the REGARDS study did not find an association of NT-proBNP with incident hypertension, but was underpowered to detect relevant smaller associations.27

Our findings contrast with prior studies in several ways. Higher NT-proBNP was associated with risk of incident hypertension in the Framingham Offspring Study9 and Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study.8 Reasons for differences from our findings might involve the use of less conservative exclusions that incorporate more participants with subclinical cardiovascular disease and, in ARIC, bias from use of participant-reported hypertension8 as a follow-up measure. These studies also had lower proportions of Black participants and less obesity than REGARDS. However, NT-proBNP appears to be cross-sectionally higher among hypertensive individuals,6,7 plausibly a consequence of myocardial and arterial stretch in the setting of increased afterload. NT-proBNP increases with severity of hypertension28 and BNP has been associated with mechanical consequences of hypertension like aortic stiffening and diastolic dysfunction.29 NT-proBNP may ultimately represent residual cardiac risk in hypertensive patients,30 as it predicts cardiovascular events31 and overall mortality32 and may predict heart failure in hypertensive individuals.33

This study has some limitations. Expressing hypertension as a dichotomy may neglect the detrimental sequelae of subthreshold blood pressure elevations.34 To capture more of the blood pressure spectrum, we planned and conducted a sensitivity analysis that used a newer definition of hypertension with lower thresholds. Furthermore, due to the multifaceted determinants of natriuretic peptides, we excluded individuals with NT-proBNP >100 pg/ml or with other conditions or prescriptions that may have affected their NT-proBNP measurement. Selection bias due to variations in follow-up among REGARDS participants is unlikely.25,35 Lastly, findings in REGARDS participants may not be generalizable to populations other than Black or White Americans.

This study has strengths. It included extensive follow-up of a racially and geographically diverse cohort. We minimized the possibility of sampling bias with preceding statistical simulations and the use of sampling weights on sex and race-specific strata in all analyses. Furthermore, the in-person measurement of blood pressure at a baseline and follow-up visit set REGARDS apart from other prospective cohort studies.

In conclusion, higher levels of NT-proBNP were not associated with risk of incident hypertension in a cohort study of Black and White adults free from prevalent hypertension. Further basic and translational research is warranted to examine the long-term interactions of natriuretic peptides with other systems regulating blood pressure.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NINDS or the NIA. Representatives of the NINDS were involved in the review of the manuscript but were not directly involved in the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data. The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the REGARDS study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating REGARDS investigators and institutions can be found at: https://www.uab.edu/soph/regardsstudy/.

Abbreviations

- BNP

B-type natriuretic peptide

- NT-proBNP

N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide

- REGARDS

REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke

FUNDING

This research project is supported by cooperative agreement U01 NS041588 co-funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and the National Institute on Aging (NIA), National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Service.

DISCLOSURE

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Forouzanfar MH, Liu P, Roth GA, Ng M, Biryukov S, Marczak L, Alexander L, Estep K, Hassen Abate K, Akinyemiju TF, Ali R, Alvis-Guzman N, Azzopardi P, Banerjee A, Bärnighausen T, Basu A, Bekele T, Bennett DA, Biadgilign S, Catalá-López F, Feigin VL, Fernandes JC, Fischer F, Gebru AA, Gona P, Gupta R, Hankey GJ, Jonas JB, Judd SE, Khang YH, Khosravi A, Kim YJ, Kimokoti RW, Kokubo Y, Kolte D, Lopez A, Lotufo PA, Malekzadeh R, Melaku YA, Mensah GA, Misganaw A, Mokdad AH, Moran AE, Nawaz H, Neal B, Ngalesoni FN, Ohkubo T, Pourmalek F, Rafay A, Rai RK, Rojas-Rueda D, Sampson UK, Santos IS, Sawhney M, Schutte AE, Sepanlou SG, Shifa GT, Shiue I, Tedla BA, Thrift AG, Tonelli M, Truelsen T, Tsilimparis N, Ukwaja KN, Uthman OA, Vasankari T, Venketasubramanian N, Vlassov VV, Vos T, Westerman R, Yan LL, Yano Y, Yonemoto N, Zaki ME, Murray CJ. Global burden of hypertension and systolic blood pressure of at least 110 to 115 mm Hg, 1990–2015. JAMA 2017; 317:165–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Whelton PK, Appel L, Charleston J, Dalcin AT, Ewart C, Fried L, Kaidy D, Klag MJ, Kumanyika S, Steffen L, Walker WG, Oberman A, Counts K, Hataway H, Raczynski J, Rappaport N, Weinsier R, Borhani NO, Bernauer E, Borhani P, de la Cruz C, Ertl A, Heustis D, Lee M, Lovelace W, O’Connor E, Peel L, Sugars C, Taylor JO, Corkery BW, Evans DA, Keough ME, Morris MC, Pistorino E, Sacks F, Cameron M, Corrigan S, Wright NK, Applegate WB, Brewer A, Goodwin L, Miller S, Murphy J, Randle J, Sullivan J, Lasser NL, Batey DM, Dolan L, Hamill S, Kennedy P, Lasser VI, Kuller LH, Caggiula AW, Milas NC, Yamamoto ME, Vogt TM, Greenlick MR, Hollis J, Stevens V, Cohen JD, Mattfeldt-Beman M, Brinkmann C, Roth K, Shepek L, Hennekens CH, Buring J, Cook N, Danielson E, Eberlein K, Gordon D, Hebert P, MacFadyen J, Mayrent S, Rosner B, Satterfield S, Tosteson H, Van Denburgh M, Cutler JA, Brittain E, Farrand M, Kaufmann P, Lakatos E, Obarzanek E, Belcher J, Dommeyer A, Mills I, Neibling P, Woods M, Goldman BJK, Blethen E. The effects of nonpharmacologic interventions on blood pressure of persons with high normal levels: results of the trials of hypertension prevention, Phase I. JAMA 1992; 267:1213–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Martinez-Rumayor A, Richards AM, Burnett JC, Januzzi JL Jr. Biology of the natriuretic peptides. Am J Cardiol 2008; 101:3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levin ER, Gardner DG, Samson WK. Natriuretic peptides. N Engl J Med 1998; 339: 321– 328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ogawa Y, Itoh H, Tamura N, Suga S, Yoshimasa T, Uehira M, Matsuda S, Shiono S, Nishimoto H, Nakao K. Molecular cloning of the complementary DNA and gene that encode mouse brain natriuretic peptide and generation of transgenic mice that overexpress the brain natriuretic peptide gene. J Clin Invest 1994; 93:1911–1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Krzesiński P, Gielerak G, Stańczyk A, Piotrowicz K, Piechota W, Skrobowski A. Association of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide and hemodynamic parameters measured by impedance cardiography in patients with essential hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens 2015; 37:148–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rivera M, Taléns-Visconti R, Salvador A, Bertomeu V, Miró V, García de Burgos F, Climent V, Cortés R, Payá R, Pérez-Boscá JL, Mainar L, Jordán A, Sogorb F, Cosín J, Mora V, Diago JL, Marín F. [NT-proBNP levels and hypertension. Their importance in the diagnosis of heart failure]. Rev Esp Cardiol 2004; 57:396–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bower JK, Lazo M, Matsushita K, Rubin J, Hoogeveen RC, Ballantyne CM, Selvin E. N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and risk of hypertension in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Am J Hypertens 2015; 28:1262–1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Freitag MH, Larson MG, Levy D, Benjamin EJ, Wang TJ, Leip EP, Wilson PW, Vasan RS; Framingham Heart Study . Plasma brain natriuretic peptide levels and blood pressure tracking in the Framingham Heart Study. Hypertension 2003; 41:978–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Apple FS, Panteghini M, Ravkilde J, Mair J, Wu AH, Tate J, Pagani F, Christenson RH, Jaffe AS; Committee on Standardization of Markers of Cardiac Damage of the IFCC . Quality specifications for B-type natriuretic peptide assays. Clin Chem 2005; 51:486–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Howard VJ, Cushman M, Pulley L, Gomez CR, Go RC, Prineas RJ, Graham A, Moy CS, Howard G. The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study: objectives and design. Neuroepidemiology 2005; 25:135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Howard G, Safford MM, Moy CS, Howard VJ, Kleindorfer DO, Unverzagt FW, Soliman EZ, Flaherty ML, McClure LA, Lackland DT, Wadley VG, Pulley L, Cushman M. Racial differences in the incidence of cardiovascular risk factors in older black and white adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017; 65:83–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ndumele CE, Matsushita K, Sang Y, Lazo M, Agarwal SK, Nambi V, Deswal A, Blumenthal RS, Ballantyne CM, Coresh J, Selvin E. N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide and heart failure risk among individuals with and without obesity: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Circulation 2016; 133:631–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Howard G, Anderson R, Johnson NJ, Sorlie P, Russell G, Howard VJ. Evaluation of social status as a contributing factor to the stroke belt region of the United States. Stroke 1997; 28:936–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sokolow M, Lyon TP. The ventricular complex in left ventricular hypertrophy as obtained by unipolar precordial and limb leads. Am Heart J 1949; 37:161–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF III, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) . A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009; 150:604–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, Cornoni-Huntley J. Two shorter forms of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression) depression symptoms index. J Aging Health 1993; 5:179–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Block G, Hartman AM, Dresser CM, Carroll MD, Gannon J, Gardner L. A data-based approach to diet questionnaire design and testing. Am J Epidemiol 1986; 124:453–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shimbo D, Levitan EB, Booth JN III, Calhoun DA, Judd SE, Lackland DT, Safford MM, Oparil S, Muntner P. The contributions of unhealthy lifestyle factors to apparent resistant hypertension: findings from the Reasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study. J Hypertens 2013; 31:370–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tsivgoulis G, Psaltopoulou T, Wadley VG, Alexandrov AV, Howard G, Unverzagt FW, Moy C, Howard VJ, Kissela B, Judd SE. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and prediction of incident stroke. Stroke 2015; 46:780–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Judd SE, Letter AJ, Shikany JM, Roth DL, Newby PK. Dietary patterns derived using exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis are stable and generalizable across race, region, and gender subgroups in the REGARDS study. Front Nutr 2014; 1:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT Jr, Roccella EJ; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee . The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003; 289:2560–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, MacLaughlin EJ, Muntner P, Ovbiagele B, Smith SC Jr, Spencer CC, Stafford RS, Taler SJ, Thomas RJ, Williams KA Sr, Williamson JD, Wright JT Jr. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2018; 71:e13–e115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rao JN, Scott AJ. The analysis of categorical data from complex sample surveys: chi-squared tests for goodness of fit and independence in two-way tables. J Am Stat Assoc 1981; 76:221–230. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Howard G, Cushman M, Moy CS, Oparil S, Muntner P, Lackland DT, Manly JJ, Flaherty ML, Judd SE, Wadley VG, Long DL, Howard VJ. Association of clinical and social factors with excess hypertension risk in black compared with white US adults. JAMA 2018; 320:1338–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Harrell FE. Ordinal logistic regression. In Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic and Ordinal Regression, and Survival Analysis. Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015, pp. 311–325. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bajaj NS, Gutiérrez OM, Arora G, Judd SE, Patel N, Bennett A, Prabhu SD, Howard G, Howard VJ, Cushman M, Arora P. Racial differences in plasma levels of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide and outcomes: the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study. JAMA Cardiol 2018; 3:11–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Belluardo P, Cataliotti A, Bonaiuto L, Giuffrè E, Maugeri E, Noto P, Orlando G, Raspa G, Piazza B, Babuin L, Chen HH, Martin FL, McKie PM, Heublein DM, Burnett JC Jr, Malatino LS. Lack of activation of molecular forms of the BNP system in human grade 1 hypertension and relationship to cardiac hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2006; 291:H1529–H1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chatzis D, Tsioufis C, Tsiachris D, Taxiarchou E, Lalos S, Kyriakides Z, Tousoulis D, Kallikazaros I, Stefanadis C. Brain natriuretic peptide as an integrator of cardiovascular stiffening in hypertension. Int J Cardiol 2010; 141:291–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chrysant SG. The clinical significance of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide in detecting the residual cardiovascular risk in hypertension and other clinical conditions and in predicting future cardiovascular events. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2016; 18:718–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Welsh P, Poulter NR, Chang CL, Sever PS, Sattar N; ASCOT Investigators . The value of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide in determining antihypertensive benefit: observations from the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial (ASCOT). Hypertension 2014; 63:507–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Paget V, Legedz L, Gaudebout N, Girerd N, Bricca G, Milon H, Vincent M, Lantelme P. N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide: a powerful predictor of mortality in hypertension. Hypertension 2011; 57:702–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ballo P, Betti I, Barchielli A, Balzi D, Castelli G, De Luca L, Gheorghiade M, Zuppiroli A. Prognostic role of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide in asymptomatic hypertensive and diabetic patients in primary care: impact of age and gender: results from the PROBE-HF study. Clin Res Cardiol 2016; 105:421–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Victor RG. Systemic hypertension: mechanisms and diagnosis. In Zipes DP (ed), Braunwald’s Heart Disease, 11th edn. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Long DL, Howard G, Long DM, Judd S, Manly JJ, McClure LA, Wadley VG, Safford MM, Katz R, Glymour MM. An investigation of selection bias in estimating racial disparity in stroke risk factors. Am J Epidemiol 2019; 188:587–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.