Abstract

Background

A postnatal care given after childbirth is a critical care to promote health and to prevent complications of the mother and newborn. However, utilization of this service is low in Ethiopia, and little is known about its coverage and determinants. Thus, this study aimed to assess the prevalence of early postnatal-care service utilization and its associated factors among mothers in Hawassa Zuria district, Sidama Regional State, Ethiopia.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted from 20 February to 20 March 2020 in Hawassa Zuria District among randomly selected 320 mothers. Data were collected by using interviewer-administered structured questionnaires. Data entered were into Epi data version 3.1 and exported to SPSS version 26 for analysis. Descriptive, bivariable, and multivariable logistic regression analysis with odds ratio and 95% confidence interval were conducted. A P value <0.05 was considered a statistically significant association. Finally, the results were presented by texts, tables, and figures.

Result

The prevalence of early postnatal-care service utilization was 29.7% (95% CI = 24.7, 35.5). Age below 25 years [AOR = 3.2 (95% CI = 1.37, 7.48)], having planned and supported pregnancy for last birth [AOR = 2.2 (95% CI = 1.13, 4.38)], having information about obstetric danger signs [AOR = 2.1 (95% CI = 1.25, 3.78)], and having positive attitude on use postnatal services [AOR = 3.5 (95% CI = 1.94, 6.32)] were factors associated with early postnatal-care utilization.

Conclusion

The finding revealed that early postnatal-care utilization in the study area was low. Strengthening family planning services, giving information on obstetrics danger signs, and creating awareness about postnatal care will improve uptake of the service in a timely manner.

1. Background

Early postnatal care (EPNC) is the care given to the mother and her newborn immediately after birth and up to the first seven days of life that marks the establishment of a new phase of family life for women and their partners and the beginning of the lifelong health record for newborn [1]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendation, the mothers have at least three postnatal-care (PNC) follow-ups by the health professionals or trained community health workers within the first 24 hours, 2-3 days, and at 7 days after delivery [2].

The care of a woman and her baby in the immediate hours, days, and weeks following birth can make an enormous difference to their long-term health and well-being. It leads to a dramatic fall in the maternal mortality rate and helps to establish and maintain contact with a number of health services needed in the short and long terms [3].

Even though it is the most neglected period for the provision of quality care services, the first week after delivery is a critical phase in the lives of a mother and her newborn. Lack of appropriate care during this period could result in a significant ill-health and even death [4].

Globally, the majority of maternal and infant mortality occurs in the first month after birth. Almost half of the postnatal maternal deaths occur within the first 24 hours, 66% occur during the first week after delivery, and one million newborns die on the first day of life. The main reasons for these easily preventable problems were poor quality of services, weak community-based heath practice, gender inequality, and poor women-centered maternity care [5, 6].

Although considerable progress has been made globally to improve maternal health, low utilization of EPNC is one of the major causes of maternal mortality and morbidity in the developing countries. Two regions, sub-Saharan Africa and South-East Asia, account for 86% of maternal mortality worldwide, and most of that occurred within 7 days after delivery. Additionally, the majority of women are not getting a PNC visit within 2 days of childbirth due to cultural practices, lack of education, shortage of income, and lack of awareness on the availability of the services [7]. In most developing countries, PNC may only be accessed if provided through home visits because of the geographical, financial, cultural, and social barriers that limit care outside the home during the early postnatal period [8].

The government of Ethiopia endorsed a strategy which is aimed at strengthening the health system to provide quality care. The Health Sector Transformation Plan 2015/16 set a target of up to 95% postnatal coverage by the year 2020 to transform all health districts by creating a high performance of primary health-care units and model kebeles [9]. However, the 2016 Ethiopian Min Demographic Health Survey reported that four in five women (81%) did not receive any PNC checkup [5], and in 2019, only 34% of women received PNC check-up in the first 2 days after birth [10].

Even though the Ethiopian government is providing free maternal and child PNC services regardless of the socioeconomic status of the women to ensure access to the community-based facilities, the maternal mortality ratio remains high at the national level, and low utilization of EPNC continued as the leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality [11].

Despite the fact that it has a very significant and positive impact on the reduction of maternal and newborn morbidity and mortality, EPNC service is yet neglected and less attention has been given to it. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of EPNC service utilization and its associated factors among mothers in Hawassa Zuria district, Sidama Regional State, Ethiopia, in 2020.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Study Setting and Period

The study was conducted in Hawassa Zuria district. Hawassa Zuria District is one of 36 districts in Sidama Regional State, Ethiopia, which is located 21 kilometers away from Hawassa, the capital of the region. The district has an estimated population number of 168,188 according to the current population projection and the estimated deliveries were 5,819. The district has 23 kebeles including three town kebeles. Currently, there are 4 public health centers, 1 primary hospital, 23 health posts, and 5 primary private clinics. The study was conducted from 20 February to 20 March 2020.

2.2. Study Design and Population

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted among postnatal mothers who had been living in Hawassa Zuria district. All mothers who gave birth six months prior to this survey in the selected kebeles were included in this study. Those who were critically sick and unable to give a response during the data collection period were excluded.

2.3. Sample Size Determination and Sampling Procedures

The sample size was determined by using the single population proportion formula with the following assumptions: considering 25.3% of postnatal-care service utilization within seven days taken from the previous study [12], 95% confidence interval, 5% marginal of error, and 10% nonresponse rate, the final sample size calculated was 320 participants. From the 23 kebeles found in Hawassa Zuria district, six kebeles were selected by a simple random sampling method. After the proportional allocation of a sample size to each kebele based on its study participants, a simple random sampling technique was used to select 320 study participants. Delivery registration book and family folders in the selected kebeles were served as a sampling frame to select the eligible women to be enrolled in this study.

2.4. Data Collection Tools, Procedures, and Quality Assurance

Data were collected by using interviewer-administered structured and pretested questionnaires developed by reviewing the related literature. The questionnaire contains sociodemographic and economic factors, reproductive and obstetrics factors, awareness of the mother on postnatal-care service, the attitude of mothers towards postnatal-care services as well as health-care providers, and facility-related factors. Data were collected by six nurses with diploma qualifications. One nurse with Bachelor of Science qualification was assigned as a supervisor. To control the quality of the data, a properly designed data collection tool was developed in English and translated into the local language (Sidaamu Afoo) and back to English by language experts to check its consistency. All data collectors and supervisors were trained for one day by the principal investigator before starting the actual data collection. Training was given on the general objective of the study, contents of the tool, and how to approach the study participants. Before starting the actual data collection, the tool was pretested on 5% of the sample population at one kebele outside the study area and necessary measures were taken accordingly. Collected data were checked for its completeness and consistency before starting actual data entry. The dependent variable was early postnatal-care service utilization that was measured by a ‘yes' or ‘no' response. Positive (yes) responses were validated by asking about the types of services utilized. Independent variables were sociodemographic and economic factors, reproductive and obstetrics factors, awareness of the mother on postnatal-care service, the attitude of mothers towards postnatal-care services as well as health-care provider, and facility-related factors.

2.5. Data Processing and Analysis

After data cleaning and checking its completeness, data were coded and entered into Epi data version 3.1 software and finally exported to statistical software for social science (SPSS) version 21 for analysis. Descriptive analysis was performed for each predictor variable, and cross tabulation was performed to see the distribution of predictor variables in relation to outcome variable. The goodness-of-fit of the model was also checked by Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-model fit. Bivariable analysis was performed for each independent variable with the outcome variable, and variables with a P value of 0.20 and below were considered as candidates for multivariable logistic regression analysis to control possible confounders and to get the final model. Adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated to determine the presence and strength of association among predictors and outcome variable. A P value of less than 0.05 was used to consider statistically significant variables. Finally, the results were described by texts, figures, and tables.

2.6. Operational Definitions

Used early postnatal-care services: if the mother used at least one PNC service in the first seven postpartum days that was provided by the health professionals regardless of the place of delivery

Awareness on the postnatal danger signs: those mothers mentioned at least one obstetrics danger sign occurred after delivery

Awareness of early postnatal care: mothers who had information about at least one postnatal-care service provided within one week after delivery

Positive attitude on postnatal care: those correctly scored above mean from attitude-related items

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

From 320 participants planned for this survey, all of them were interviewed. The mean age of the respondents was 29.1 ± 5.8 years. Of the interviewed respondents, 257 (80.3%) were protestant. About 263 (82.2%) of them were from the Sidama ethnic group. 311 (97.2%) of them were married, and 151 (47.2%) attended primary schools. 254 (79.4%) of the respondents had either TV and/or radio in their house (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants in Hawassa Zuria district, Sidama Regional State, Ethiopia, 2020.

| Variables | Categories | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | <25 | 125 | 39.1 |

| 25–35 | 119 | 37.2 | |

| >35 | 76 | 23.8 | |

|

| |||

| Religion | Protestant | 257 | 80.3 |

| Muslim | 44 | 13.8 | |

| Orthodox | 19 | 5.9 | |

|

| |||

| Residence | Urban | 25 | 7.8 |

| Rural | 295 | 92.2 | |

|

| |||

| Marital status | Married | 290 | 90.6 |

| Unmarried | 19 | 5.9 | |

| Widowed | 11 | 3.5 | |

|

| |||

| Mother's educational status | Secondary and above | 69 | 21.6 |

| Primary school | 151 | 47.2 | |

| No formal education | 100 | 31.3 | |

|

| |||

| Husband educational status | Secondary and above | 139 | 43.5 |

| Primary school | 162 | 50.6 | |

| No formal education | 19 | 5.9 | |

|

| |||

| Mother's occupation | Employer | 27 | 8.4 |

| Student | 64 | 20 | |

| Merchant | 103 | 32.2 | |

| Housewife | 126 | 39.4 | |

|

| |||

| Husband's occupation | Farmer | 131 | 40.9 |

| Employer | 59 | 18.4 | |

| Merchant | 110 | 34.4 | |

| Daily labor | 20 | 6.3 | |

|

| |||

| Monthly income | >1500 ETB | 120 | 55.9 |

| 1000–1500 ETB | 39 | 12.2 | |

| <1000 ETB | 102 | 31.9 | |

|

| |||

| Have mass media | Yes | 254 | 79.4 |

| No | 66 | 20.6 | |

ETB = Ethiopian Birr.

3.2. Obstetrics Complications and Reproductive Characteristics of the Study Participants

One hundred and ninety-four (60.6%) of the respondents had less than four children. Two hundred and sixty-one (86.1%) had one or more ANC follow-ups during their last pregnancy; out of these, only 96 (36.8%) had four or more ANC visits. The common complications faced after delivery were vaginal bleeding (9.1%) followed by severe abdominal pain (6.6%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Obstetrics complications and reproductive characteristics of the study participants in Hawassa Zuria district, Sidama Regional State Ethiopia, 2020.

| Variables | Categories | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parity | <4 | 194 | 60.6 |

| ≥4 | 126 | 39.4 | |

| Condition of pregnancy | Planned and supported | 147 | 45.9 |

| Unplanned but supported | 83 | 26.0 | |

| Unplanned and unsupported | 90 | 28.1 | |

| Had ANC visit | Yes | 261 | 81.6 |

| No | 59 | 18.4 | |

| Had complication during pregnancy | Yes | 68 | 21.3 |

| No | 252 | 78.8 | |

| Had complication during delivery | Yes | 65 | 20.3 |

| No | 255 | 79.7 | |

| Had complication after delivery | Yes | 76 | 23.8 |

| No | 244 | 76.2 | |

| Mode of delivery for the last birth | Normal | 240 | 75.0 |

| Instrumental | 54 | 16.9 | |

| Surgery | 26 | 8.1 |

3.3. Awareness and Attitude of the Study Participants towards EPNC Services

More than half (55%) had awareness on the EPNC services. Regarding obstetric danger signs, 135 (42.2%) have mentioned at least one danger sign. The most commonly mentioned signs were vaginal bleeding (26.7%) followed by severe abdominal pain (26.7%). Concerning respondents' attitudes toward EPNC utilization, the mean attitude score was 25 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Awareness and attitude of the study participants on EPNC services and danger signs after birth in Hawassa Zuria district, Sidama Regional State, Ethiopia, 2020.

| Variables | Categories | Frequencies | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Had awareness on EPNC | Yes | 176 | 55.0 |

| No | 144 | 45.0 | |

| Had awareness on postnatal danger sign | Yes | 135 | 42.2 |

| No | 185 | 57.8 | |

| Common postnatal danger signs mentioned | Vaginal bleeding | 85 | 26.7 |

| Severe abdominal pain | 85 | 26.7 | |

| Headache | 55 | 17.0 | |

| High-grade fever | 50 | 15.6 | |

| Blurring of vision | 45 | 14.0 | |

| Attitude towards EPNC | Positive | 175 | 54.7 |

| Negative | 145 | 45.3 |

3.4. Health Facility and Health Workers Related Factors for EPNC

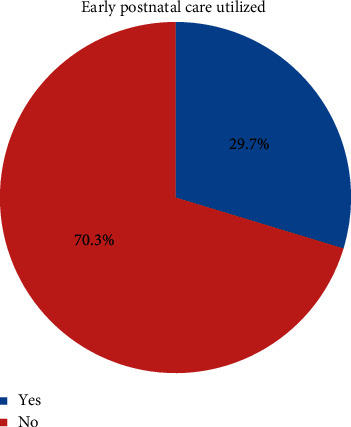

Concerning the time taken to get to the services, more than half (55.9%) of them traveled at least 30 minutes to reach the health facility. The majority of the respondents (89.1%) used health facility delivery services for their last birth. Only 95 (29.7%) of them used EPNC for recent delivery (Figure 1). The main reasons mentioned by the respondents for not using EPNC services were lack of information followed by lack of time (Table 4).

Figure 1.

Magnitude of early postnatal-care services utilized by the respondents in Hawassa Zuria District, Sidama Regional State, Ethiopia, 2020.

Table 4.

Health-care provider and facility-related factors affecting utilization of EPNC in Hawassa Zuria district, Sidama Regional State, Ethiopia 2020.

| Variables | Categories | Frequencies | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time taken to reach health facility | <30 minutes | 179 | 55.9 |

| 30 min–1 hour | 118 | 36.9 | |

| >1 hour | 23 | 7.2 | |

| Place of delivery | Health facility | 285 | 89.1 |

| Home | 35 | 10.9 | |

| Appointed by health professionals for EPNC (n = 285) | Yes | 136 | 47.7 |

| No | 149 | 52.3 | |

| Time of stay at health facility after delivery (n = 285) | ≥24 hours | 138 | 48.4 |

| <24 hours | 147 | 51.6 | |

| Reasons for not using EPNC services | Lack of information | 90 | 40.0 |

| Lack of time | 70 | 31.0 | |

| Unwanted pregnancy | 35 | 15.6 | |

| Far health facility | 30 | 13.4 |

3.5. Factors Associated with EPNC Service Utilization

To identify the association of independent variables with the outcome variable (utilization of EPNC), both bivariate and multivariable logistic regression analysis were performed. In bivariable logistic regression analysis age of the mother, educational status of the mother, the number of children alive, history of ANC follow-up for the last pregnancy, condition of the last pregnancy, complications faced during the last pregnancy and after delivery, awareness on obstetrics danger signs, and attitude towards EPNC services were variables associated with EPNC service utilization.

In multivariable logistic regression analysis after controlling for potential confounder, age of the mother, having planned and supported pregnancy, having awareness on obstetric danger signs, and having a positive attitude towards EPNC services were the factors statistically associated with the outcome variable (EPNC service utilization).

Mothers whose age was below 25 years were 3.2 times more likely to utilize early postnatal-care services when compared with those whose age was above 35 years [AOR = 3.2, 95% CI (1.37, 7.53)]. Those mothers who had planned and supported pregnancy for their last birth were 2.28 times more likely to utilize early postnatal-care services than those who had unplanned and unsupported pregnancy for their last pregnancy [AOR = 2.28, 95% CI (1.15, 4.52)].

Mothers who had awareness on obstetric danger sign and symptoms were 2.2 times more likely to utilize early postnatal-care services when compared with those who had no awareness [AOR = 2.2, 95% CI (1.27, 3.87)]. Mothers who had a positive attitude towards EPNC-care services were 3.5 times more likely to utilize early postnatal care when compared with those who had negative attitude [AOR = 3.5, 95% CI (1.95, 6.33)] (Table 5).

Table 5.

Factors associated with EPNC service utilization in Hawassa Zuria district, Sidama Regional State, Ethiopia, 2020.

| Variables and categories | Utilized EPNC | COR (95%CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Age of the respondents | ||||

| <25 | 52 | 73 | 3.45 (1.72, 6.91) | 3.22 (1.37, 7.53) ∗ |

| 25–35 | 30 | 89 | 1.63 (0.79, 3.37) | 1.64 (0.73, 3.63) |

| >35 | 13 | 63 | 1 | 1 |

|

| ||||

| Educational status of the mother | ||||

| Secondary school and above | 41 | 59 | 2.73 (1.34, 5.54) | 1.23 (0.56, 2.68) |

| Primary school | 40 | 111 | 1.41 (0.71, 2.82) | 1.76 (0.78, 3.93) |

| No normal education | 14 | 59 | 1 | 1 |

|

| ||||

| Parity | ||||

| <4 | 66 | 128 | 1.72 (1.03, 2.87) | 1.45 (0.73, 2.88) |

| ≥4 | 29 | 97 | 1 | 1 |

|

| ||||

| Condition of the last pregnancy | ||||

| Planned and supported | 58 | 89 | 2.60 (1.41, 4.81) | 2.28 (1.15, 4.52) ∗ |

| Unplanned but supported | 19 | 64 | 1.18 (0.57, 2.45) | 1.11 (0.48, 2.57) |

| Unplanned and unsupported | 18 | 72 | 1 | 1 |

|

| ||||

| Had ANC visit | ||||

| Yes | 80 | 181 | 1.29 (0.68, 2.46) | 0.75 (0.35, 1.60) |

| No | 15 | 44 | 1 | 1 |

|

| ||||

| Faced complication during last pregnancy | ||||

| Yes | 26 | 42 | 1.64 (0.93, 2.88) | 1.42 (0.72, 2.79) |

| No | 69 | 183 | 1 | 1 |

|

| ||||

| Faced complication after delivery | ||||

| Yes | 30 | 46 | 1.79 (1.04, 3.08) | 1.88 (0.99, 3.58) |

| No | 65 | 179 | 1 | 1 |

|

| ||||

| Had awareness on obstetric danger sign and symptoms | ||||

| Yes | 55 | 80 | 2.49 (1.52, 4.069) | 2.21 (1.27, 3.87) ∗ |

| No | 40 | 145 | 1 | 1 |

|

| ||||

| Attitude towards EPNC | ||||

| Positive | 71 | 104 | 3.44 (2.022, 5.858) | 3.50 (1.95, 6.33) ∗∗ |

| Negative | 24 | 121 | 1 | 1 |

∗Statistically significant at P < 0.05, ∗∗statistically significant at P < 0.001.

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the EPNC practices in Hawassa Zuria district, Sidama Regional State, Ethiopia. According to this study, the level of EPNC service utilization was found to be 29.7% (95% CI: 24.7, 35.5). This result was similar to the findings from the study conducted in rural Myanmar (25.20%), Northern Shoa, Ethiopia (28.4%), and Debre Markos town (33.5%) [13–15]. The reason for this consistency may be the similarity of the study design and setting and sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants.

This result was higher than the previous findings from eastern Uganda (15.4%), Aseko District (23.7%), and Mertule Mariam District (19%) [16–18]. This may be attributed to the time difference, and there could be improvement in accessing and utilizing health-care service through time.

However, this result was lower when compared with previous findings in Benin (68.42%), Addis Ababa (65.6%), and Shebe Sombo district, Jimma Zone (58.5%) [19–21]. The most likely reason for this discrepancy may be due to the place of residence and geographical variation. The difference also may be due to that the previous studies considered postpartum mothers up to forty-two days. As a result, the chance of utilizing the service could be increased when compared with this study which considered only the first week of the postpartum period.

In view of addressing the different factors in influencing the practices of EPNC services in the study area, an attempt was made to examine the associations between various explanatory variables and the outcome variables. The study identified four variables which have positive significant associations with early postnatal-care service utilization.

This study revealed that younger mothers whose age was below 25 years were 3.2 times more likely to practice EPNC services [AOR = 3.2, 95% CI (1.37, 7.53)] when compared with older ones. This was also seen in previous studies conducted in Shebe Sombo and Fiche town, Oromia Region, Ethiopia [21, 22]. This may be because younger mothers were more likely to have greater exposure to mass media and more access to education. However, this finding was in contrast with previous findings from Farta district, south Gondar Zone in Ethiopia and Tanzania [23, 24].

The odds of having EPNC services were 2.28 times more likely [(AOR = 2.2, 95% CI (1.15, 4.52)] among those mothers who had planned and supported pregnancy when compared with those whose pregnancy was unplanned and unsupported. This finding was in line with the previous study conducted in Debre Tabour town and Tigray Region, Ethiopia [25, 26]. This may be because mothers' interests to use EPNC services can be increased based on the condition of the pregnancy, whether they are planned and supported.

Awareness on potential postnatal danger signs has a positive association with EPNC utilization. Mothers who have mentioned at least one obstetric danger sign and symptom were 2.2 times more likely [AOR = 2.2, 95% CI (1.27, 3.87)] to utilize EPNC service as compared to those who had no awareness on obstetric danger signs and symptoms This finding was supported by the previous study conducted in Diga district, West Wollega, and Lemo district, Ethiopia [27, 28]. This can be explained by the fact that awareness of obstetrics danger sign is an important factor in triggering and motivating the mothers to seek health-care services as soon as possible with the aim of preventing, diagnosing, and even treating the case if problem exists.

Finally, attitude towards EPNC service also had a positive association with EPNC service utilization. Mothers who had a positive attitude towards EPNC were 3.5 times more likely to utilize EPNC services [AOR = 3.50, 95% CI (1.95, 6.33)] when compared with those who had negative attitude. This finding was consistent with that of previous studies which reported that a respondent's attitude was a critical factor in encouraging a mother to receive EPNC services [29]. This result was also supported by the previous study conducted in Bahi District, Tanzania [30]. The most likely explanation for this might be that a positive attitude is the most valuable precondition for any healthy behavior; as a result, it might encourage adaptation and practices of healthy personal behavior that help to improve an individual's health status.

5. Conclusions

This study revealed that the coverage of early postnatal-care service utilization was low in the study area. Age of the respondents, having planned and supported pregnancy, having awareness on obstetrics danger signs, and having a positive attitude towards EPNC service were factors significantly associated with the utilization of EPNC service. Strengthening family planning services, giving information on obstetrics danger signs and symptoms, and creating awareness on benefits of EPNC will increase uptake of the service in a timely manner.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Hawassa University College of Medicine and Health Sciences, School of Public Health, for its support to conduct this study. The authors would like to thank the study participants, data collectors, supervisors, and all Hawassa Zuria District Health Office workers.

Abbreviations

- ANC:

Antenatal care

- AOR:

Adjusted odds ratio

- COR:

Crude odds ratio

- EPNC:

Early postnatal care

- PNC:

Postnatal care

- SPSS:

Statistical package for social science

- WHO:

World Health Organization.

Data Availability

The finding of this study is generated from the data collected and analyzed based on stated methods and materials. The original data supporting these findings are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethical Approval

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Hawassa University College of Medicine and Health science. Official permission letters were obtained from Hawassa Zuria District Health Office.

Consent

After informing aims, risks, and benefits of the study and assuring confidentiality of the information, verbal informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

SY contributed to conception design and analysis and interpretation of data. AD and AD codesigned, analyzed, prepared, and revised the manuscript. Finally, all authors gave final approval of the version to be published.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Postnatal Care for Mothers and Newborns: Highlights from the World Health Organization 2013 Guidelines. Vol. 25. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Postnatal Care of the Mother and Newborn. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis L. Essential midwifery practice: postnatal care. Essentially Midirs. 2011;2(5) [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Postnatal care for mothers and newborns: highlights from the World Health Organization 2013 guidelines. Postnatal Care Guidelines. 2015;4 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bongaarts J., WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA World bank group, and united nations population division trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015 geneva: World health organization, 2015. Population and Development Review. 2016;42(4):p. 726. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warren C., Daly P., Toure L., Mongi P. Postnatal Care. Opportunities for Africa’s Newborns Cape Town, South Africa: Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2006. pp. 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Trends in Maternal Mortality 2000 to 2017: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA. Washington, DC, USA: World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sines E., Syed U., Wall S., Worley H. Postnatal Care: A Critical Opportunity to save Mothers and Newborns. 2007. Washington, DC, USA: Population Reference Bureau; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Minister of Health. Health Sector Transformation Plan 2015/16‐2019/20 (2008‐2012 EFY) Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.The DHS Program ICF. 2016. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016: key indicators report. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centeral Statistical Agency of Ethiopia. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Rockville, MD, USA: CSA and ICF; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melese T. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Postnatal Care within One Week Utilization Among Women Who Had Given Birth in the Last Six Weeks in Ameya District, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Addis Ababa University; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akibu M., Tsegaye W., Megersa T., Nurgi S. Prevalence and determinants of complete postnatal care service utilization in Northern Shoa, Ethiopia. Journal of Pregnancy. 2018;2018:7. doi: 10.1155/2018/8625437.8625437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mon A. S., Phyu M. K., Thinkhamrop W., Thinkhamrop B. Utilization of full postnatal care services among rural Myanmar women and its determinants: a cross-sectional study. F1000Research. 2018;7 doi: 10.12688/f1000research.15561.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Limenih M. A., Endale Z. M., Dachew B. A. Postnatal care service utilization and associated factors among women who gave birth in the last 12 months prior to the study in Debre Markos Town, Northwestern Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. International Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/7095352.7095352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Izudi J., Akwang G. D., Amongin D. Early postnatal care use by postpartum mothers in Mundri East County, South Sudan. BMC Health Services Research. 2017;17(1):p. 442. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2402-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teklehaymanot A., Niguse D., Tesfay A. Early postnatal care service utilization and associated factors among mothers who gave birth in the last 12 Months in Aseko District, Arsi Zone, south East Ethiopia in 2016. Journal of Women’s Health Care. 2017;6(1):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kebede S. D., Roba K. T., Assefa N., Munye T., Alebachew W. Prevalence and predictors of postpartum care uptake among mothers who gave birth in the last six months in Mertule Mariam District northwest Ethiopia. American Journal of Nursing. 2019;8(4):135–141. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dansou J., Adekunle A. O., Arowojolu A. O. Factors associated with the compliance of recommended first postnatal care services utilization among reproductive age women in Benin Republic: an analysis of 2011/2012 BDHS data. International Journal of Reproduction, Contraception, Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2017;6(4):1161–1169. doi: 10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20171378. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berhanu S., Sr., Asefa Y., Giru B. W. Prevalence of postnatal care utilization and associated factors among women who gave birth and attending immunization clinic in selected government health centers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Prevalence. 2016;26 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chemir F., Gelan M., Sinaga M. Postnatal care service utilization and associated factors among mothers who delivered in Shebe Sombo Woreda, Jimma Zone, Ethiopia. International Journal of Women’s Health and Wellness. 2018;4(078):2474–1353. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shukure R., Mohammed H., Wudmetas A., Mohammed S. Assessment of knowledge and factors affecting utilization of postnatal care in Fiche Town, Oromia Region, Ethiopia. International Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 2018;1(2):28–33. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohan D., Gupta S., LeFevre A., Bazant E., Killewo J., Baqui A. H. Determinants of postnatal care use at health facilities in rural Tanzania: multilevel analysis of a household survey. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2015;15(1):p. 282. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0717-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sisay M. M., Geremew T. T., Demlie Y. W., et al. Spatial patterns and determinants of postnatal care use in Ethiopia: findings from the 2016 demographic and health survey. BMJ Open. 2019;9(6) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025066.e025066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wudineh K. G., Nigusie A. A., Gesese S. S., Tesu A. A., Beyene F. Y. Postnatal care service utilization and associated factors among women who gave birth in Debretabour town, North West Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2018;18(1):p. 508. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-2138-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berhe A., Bayray A., Berhe Y., et al. Determinants of postnatal care utilization in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2019;14(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belachew T., Taye A., Belachew T. Postnatal care service utilization and associated factors among mothers in Lemo Woreda, Ethiopia. Journal of Women’s Health Care. 2016;5 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heyi W. D., Deshi M. M., Erana M. G. Determinants of postnatal care service utilization in Diga District, East Wollega Zone, Wester Ethiopia: case-control study. Ethiopian Journal of Reproductive Health. 2018;10(4) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alemayeh H., Assefa H., Adama Y. Prevalence and factors associated with post natal care utilization in Abi-Adi Town, Tigray, Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. IJPBSF International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biological Sciences Fundamentals. 2014;8(1):23–35. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lwelamira J., Safari J., Stephen A. Utilization of maternal postnatal care services among women in selected villages of Bahi District, Tanzania. Current Research Journal of Social Sciences. 2015;7(4):106–111. doi: 10.19026/crjss.7.1690. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The finding of this study is generated from the data collected and analyzed based on stated methods and materials. The original data supporting these findings are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.