Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in dramatic changes to sleep patterns and higher prevalence of insomnia, which threaten overall mental and physical health. We examined whether safety behaviors in response to COVID-19, worry in response to COVID-19, and depression predicted insomnia, with age, race, and sex as covariates. A community sample from the United States (n = 321, Mage = 40.02, SD = 10.54; 53.6% female) recruited using online crowdsourcing completed self-report measures in May of 2020 and again three months later. At baseline, our model accounted for 68.1% of the variance in insomnia, with depression as the only significant predictor (β = .70, p < .001). In the longitudinal analyses, only baseline insomnia symptoms predicted 3-month follow-up insomnia symptoms (β = .70, p < .001; 67.1% of variance). Of note, COVID-19 worry and some COVID-19 safety behaviors were related to 3-month follow-up safety behaviors, but not insomnia. Our findings demonstrated that depression is an important factor to consider for concurrent insomnia symptoms. Our results have implications regarding the development of interventions for insomnia during the COVID-19 pandemic and suggest that clinicians should consider depression when assessing for and treating insomnia symptoms.

Keywords: insomnia, COVID-19 worry, depression, transdiagnostic, SEM

Sleep is important for survival, and inadequate sleep results in negative consequences for functioning (Fortier-Brochu et al., 2012; Kyle et al., 2010). Sleep disturbance often occurs during times of increased stress, such as the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, and is thought to be a natural consequence of stress (Lavie, 2001; Morin et al., 2020). However, sleep disturbance associated with an acute stressful event can lead to long-term negative sleep patterns, and insomnia has been identified as a risk factor for other psychological and medical disorders (see Lavie, 2001 and Vargas & Perlis, 2020 for reviews).

Several studies worldwide have reported a higher prevalence of clinical insomnia during the COVID-19 pandemic, ranging from 17.4% in an Italian community sample to 38.9% in a meta-analysis with healthcare workers (Killgore et al., 2020; Kokou-Kpolou et al., 2020; Marelli et al., 2020; Pappa et al., 2020; Rosaria Gualano et al., 2020; Voitsidis et al., 2020). Pandemic data suggest women (Marelli et al., 2020; Rosaria Gualano et al., 2020; Voisidis et al., 2020), students (compared to workers; Marelli et al., 2020), individuals with chronic or pre-existing medical conditions (Kokou-Kpoulou et al., 2020; Rosaria Gualano et al., 2020), individuals with high school and college education (compared to post-graduates; Kokou-Kpolou et al., 2020), and individuals who live in urban areas (Voitsidis et al., 2020) report higher insomnia symptoms. However, existing COVID-19 studies of insomnia have been cross-sectional, and additional work is needed to study the mechanism and interactions involving risk factors of insomnia over time.

In addition to increased insomnia during the ongoing COVID-19 crisis, higher rates of depressive symptoms have also been reported (González-Sanguino et al., 2020; Killgore et al., 2020; Kokou-Kpolou et al., 2020; Marelli et al., 2020; Pappa et al., 2020; Rosaria Gualano et al., 2020; Voitsidis et al., 2020; Wang, Pan, et al., 2020), which has been true in other public health crises (see Brooks et al., 2020 for a review). One COVID-19 study found that severe depressive symptoms during COVID-19 were related to concurrent insomnia (Voitsidis et al., 2020). Brooks et al. (2020) state that the impact of the quarantine on depression symptoms could be long-lasting, with at least one study reporting higher depressive symptoms years after quarantine ended. Collectively, this work demonstrates the need for longitudinal research to understand the mechanism underlying the increase in depressive symptoms and their relationship to insomnia during the present pandemic.

Additionally, higher rates of anxiety symptoms have been reported during the current pandemic (Lin et al., 2020; Marelli et al., 2020; Pappa et al., 2020; Patsali et al., 2020; Rosaria Gualano et al., 2020; Rossi et al., 2020; Voitsidis et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020) and anxiety-related risk factors of insomnia that are thought to span across disorders (i.e., transdiagnostic) have recently received attention. One such risk factor is COVID-19 worry, with higher anxiety specific to COVID-19 related to more severe concurrent insomnia symptoms in at least three samples (Killgore et al., 2020; Kokou-Kpolou et al., 2020; Voitsidis et al., 2020). Unfortunately, these studies included either new COVID-19 worry questions that were not validated (Kokou-Kpolou et al., 2020; Voitsidis et al., 2020) or an adapted SARS stress scale to assess COVID-19 worry (Killgore et al., 2020).

COVID-19 worry is similar to anxiety-related transdiagnostic risk factors identified with previous public health crises. Brooks et al. (2020) reported common anxiety symptoms during prior public health crises, including fear of infection and anxiety specific to having inadequate supplies, insufficient information, and financial matters. Overall, the studies suggested psychological effects associated with quarantine-specific stressors lasting for several months after quarantine (Brooks et al., 2020). These preliminary reports demonstrate the value of considering COVID-19-specific transdiagnostic risk factors when studying insomnia, but further research is necessary to investigate the long-term effects of COVID-19 worry.

One factor that has been understudied in relation to insomnia is the influence of COVID-19-related safety behaviors. A review of existing COVID-19 scales failed to identify any subscales with a focus on behavior, though a few scales included single items to assess aspects of behavior (Chandu et al., 2020). In addition to fear-related factors, Taylor et al. (2020) identified compulsive behaviors that are associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, including checking the news or seeking reassurance from others. Another scale, the COVID-19 Phobia Scale (Arpaci, Karataş, & Baloğlu, 2020) has a few items referring to behaviors (e.g., avoiding individuals who sneeze). Since the publication of the review, the COVID-19 Safety Behaviors Scale (Schmidt et al., 2020) has been created and contains three subscales including stockpiling (e.g., “Stockpiling food and water”), cleaning (e.g., “Disinfecting home”), and avoiding (e.g., “Avoided eating out”), representing behaviors specific to the COVID-19 pandemic. Although this scale fills an important gap in the literature, there has yet to be research relating COVID-19 specific safety behaviors to insomnia symptoms.

Overall, although rates of depression, anxiety, and insomnia during the ongoing pandemic are higher, the general relationship among these variables appears to be similar to the existing literature prior to the pandemic, although there are limited studies to date. Pre-COVID-19 research generally suggests that the relationship between insomnia and depression is bidirectional, with depression acting as a risk factor for insomnia symptoms and insomnia included as a symptom of depression (see Alvaro et al., 2013 and Vargas & Perlis, 2020 for reviews). Lauriola et al. (2019) identified a significant, though indirect, association between anxiety-related risk factors (i.e., intolerance of uncertainty and anxiety sensitivity) and insomnia through a direct relationship between anxiety disorders and insomnia. This suggests that the relationship between depression and insomnia may be confounded with anxiety-related risk factors, though this work remains preliminary.

In the present study, we explored whether two COVID-19 related transdiagnostic factors (safety behaviors in response to COVID-19; worry in response to COVID-19) and depression predict insomnia. Age, race, and sex were included as covariates based on prior literature demonstrating sociodemographic differences in insomnia prevalence before COVID-19 (American Psychiatric Association 2013) and also during the pandemic (Wang, Zhu, et al., 2020). In addition, COVID-19 has been found to differentially impact Black and Latinx individuals in the U.S. (Figueroa et al., 2021; Ruprecht et al., 2020), which may result in additional stressors. By including the above covariates, depression, and two transdiagnostic risk factors into a single model, we examined potential mechanisms underlying insomnia during the present crisis. Given the lack of research on COVID-19-specific factors, as an exploratory aim we investigated the relationship between COVID-19-related safety behaviors and COVID-19 worry. We assessed these mechanisms using two waves of data collection three months apart to determine the temporal relationship between these constructs.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Participants were recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk (Mturk) to participate in a larger online longitudinal study. Participation involved the completion of a battery of online self-report measures during May of 2020 and again three months later (beginning in August of 2020). Access to this study was restricted to participants over 18 years of age who were located in the United States. Participants had to have an approval rating of at least 95% with a minimum of 100 surveys (i.e., Peer et al., 2014). Prior to participation, participants indicated they understood the study procedures and provided informed consent before completing the online measures. Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Ohio University and the study was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. At each wave, participants were compensated $4.25 for completing the online measures and an additional $1.25 if they had a child between the ages of 4 and 11 and agreed to complete additional measures. Due to emerging evidence that traditional attention check items can be circumvented using automatic or “bot” responding (e.g., Pei et al., 2020), three attention check items using both adversarial questioning (i.e., referring to alternative answers in the questions) and typographical errors to prevent “bot” identification of words (i.e., se1ected) were included in the study. All individuals who passed attention checks in the baseline administration were included in the first model. In the longitudinal model, only individuals who passed attention checks at both baseline and 3-month follow-up were included. The data used in the present analysis were from the administration of the questionnaires at baseline and 3-month follow-up.

Baseline

Demographic characteristics for our sample across both baseline and 3-month follow-up are provided in Table 1. The baseline sample comprised 900 participants. Those who failed any attention check item were excluded (n = 265). The final sample contained 635 participants at baseline (Mage = 38.52 years, SD =10.00; 49.0% female). Data collection for baseline administration began on 4/29/2020 with the modal response date being 4/29/2020. Most participants identified as White (n = 520, 81.9%). A small number of participants identified as Hispanic or Latino (n = 71, 11.2%). Within this sample, 46.5% of participants endorsed a four-year college degree (BA, BS) as their highest level of education achieved. Most participants reported an estimated yearly family income of $75,000 or less (60.5%).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics across waves

| Baseline n = 635 |

3-month follow-up n = 321 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | M (SD) | |

| Age | 38.52 (10.00) | 40.02 (10.54) |

| n (%) | ||

| Sex at birth | ||

| Male | 323 (50.9%) | 148 (46.1%) |

| Female | 311 (49.0%) | 172 (53.6%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.3%) |

| Race | ||

| White or Caucasian | 520 (81.9%) | 280 (87.2%) |

| Black or African American | 77 (12.1%) | 29 (9.0%) |

| Asian | 44 (6.9%) | 17 (5.3%) |

| American Indian/Native American/Alaskan Native | 13 (2.0%) | 6 (1.9%) |

| Pacific Islander | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Other | 6 (0.9%) | 2 (0.6%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.3%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 71 (11.2%) | 17 (5.3%) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 556 (87.6%) | 303 (94.4%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 8 (1.3%) | 1 (0.3%) |

| Estimated Yearly Family Income | ||

| < $10,000 | 14 (2.2%) | 8 (2.5%) |

| $10,000–25,000 | 58 (9.1%) | 34 (10.6%) |

| $25,000–40,000 | 94 (14.8%) | 41 (12.8%) |

| $40,000–75,000 | 218 (34.3%) | 103 (32.1%) |

| $75,000–100,000 | 126 (19.8%) | 63 (19.6%) |

| $100,000–150,000 | 75 (11.8%) | 46 (14.3%) |

| >$150,000 | 41 (6.5%) | 19 (5.9%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 9 (1.4%) | 7 (2.2%) |

Note. Participants could select more than one race option, therefore the percentages are non-mutually exclusive.

3-month follow-up

The 3-month follow-up sample comprised 459 participants. Those who failed any attention check item were excluded (n = 138). The final sample contained 321 participants at 3-month follow-up (Mage = 40.02 years, SD = 10.54; 53.6% female). Data collection for 3-month follow-up administration began on 8/07/2020 with the modal response date being 8/07/2020. Most participants identified as White (n = 280, 87.2%). A small number of participants identified as Hispanic or Latino (n = 17, 5.3%). Within this sample, 43.0% of participants endorsed a four-year college degree (BA, BS) as their highest level of education achieved. Most participants reported an estimated yearly family income of $75,000 or less (57.9%).

Measures

COVID-19 Safety Behaviors Scale (COVID-19 SB; Schmidt et al., 2020)

This scale was developed by Schmidt and colleagues (2020) to measure behavioral patterns in response to the COVID-19 outbreak. Participants responded to this scale by rating the extent to which they “have engaged in the following behaviors in response to COVID-19” using a five-point scale (from 0 = “Not at all” to 4 = “Very much”). The COVID-19 SB comprises three subscales representing stockpiling (e.g., “Stockpiling food and water”), cleaning (e.g., “Disinfecting home”), and avoiding (e.g., “Avoided eating out”) behaviors in response to the threat posed by the COVID-19 outbreak. Due to evidence that the COVID-19 safety behaviors are distinct (Schmidt et al., 2020), stockpiling, cleanliness, and avoidance were modelled as separate factors. The McDonald coefficient omega (coefficient ω; McDonald, 1970, 1999) showed good to excellent internal consistency for the three scales at baseline (ω’s ranging from .83 to .92) and 3-month follow-up (ω’s ranging from .85-.92).

COVID-19 Distress and Worries Scale (COVID-19 DAWS; Schmidt et al., 2020)

This 25-item scale was created to measure worry and distress in response to the outbreak of COVID-19. The items on the COVID-19 DAWS use a five-point scale (from 0 = “Not at all” to 4 = “Very Much”). Participants rated each item based on the degree to which it has caused distress in the current pandemic. The COVID-19 DAWS is a higher-order construct composed of three lower-order dimensions representing financial worries (e.g., “I worry I will be unable to provide for my family during this time of COVID-19”), health worries (e.g., “I worry that I am going to contract COVID-19”), and catastrophizing worries (e.g., “I worry that if I go into quarantine, I will go crazy”) in response to the threat posed by the COVID-19 outbreak. COVID-19 worries will be captured as the second-order COVID-19 DAWS factor. This measure showed excellent internal consistency at baseline (ω = .90) and good internal consistency at 3-month follow-up (ω = .87).

Insomnia Severity Index (ISI; Bastien, Vallières, & Morin, 2001)

The ISI is a seven-item self-report questionnaire designed to assess sleep difficulties (i.e., falling asleep, staying asleep, waking too early), satisfaction/dissatisfaction with sleep patterns, and/or interference with daily functioning (e.g., “How worried/distressed are you about your current sleep problem?”). Three initial questions assess for severity of insomnia problems over the last two weeks (i.e., “Please rate the current [i.e., last two weeks] severity of your insomnia problem[s]”). Participants are asked to rate all items using a five-point Likert-type scale, with higher scores reflecting more severe sleep problems and greater dissatisfaction with sleep. The ISI showed excellent internal consistency in this sample at baseline (ω = .92) and 3-month follow-up (ω = 1.00).

The Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS; Watson et al., 2007)

The IDAS is a 64-item scale developed to assess symptoms of major depression and anxiety disorders. The IDAS is comprised of multiple specific symptom scales measuring suicidality, lassitude, insomnia, appetite loss, appetite gain, ill temper, well-being, panic, social anxiety, and traumatic intrusions. The IDAS also contains two broad subscales: the General Depression and Dysphoria subscales. Scores on the 20-item Depression scale of the IDAS were utilized in the present analyses, which assesses symptoms of depressed mood, anhedonia, suicidality, lassitude, appetite loss, and well-being and also include the 10-item Dysphoria subscale. The items use a five-point scale (from 1 = “Not at all” to 5 = “Extremely”) to rate the degree to which each experience was present over the course of the past two weeks. Items 10, 12, and 35 were omitted from the study due to overlap with insomnia symptoms. Item 51 was inadvertently omitted from baseline administration. At baseline, the coefficient-ω estimate for the IDAS Depression scale score was excellent (ωs = .91).

Missing data

Planned missingness was used in the present study. Based on recommendations by Rhemtulla and colleagues (2014), planned missingness was used to expand the variables to be collected without increasing participant burden. Participants were given 80% of each subscale for the IDAS and 80% of items 4–7 for the ISI. Robust maximum likelihood (MLR) was used to account for the planned missing data design in the sample.

Data analytic plan

Demographic characteristics and the means and correlations among study variables were first calculated using SPSS version 26. Following this, a series of structural equation models (SEMs) were fit using Mplus version 8.4 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2017). To examine the cross-sectional relations between COVID-19-related worries and behaviors, insomnia, depression, and relevant covariates, an SEM was fit including the following baseline variables as independent variables: a second-order COVID-19 worry factor, COVID-19 stockpiling, cleaning, and avoiding factors, a depression factor, and time under stay at home order, age, sex, and race. The latent Insomnia variable was treated as the dependent variable. As the IDAS depression scale contains 10 items capturing general dysphoria and 2 items capturing each of 4 depression symptoms (suicidality, lassitude, appetite loss, well-being; insomnia was removed for these analyses), residual correlations were allowed between all items from the same symptom clusters. All data were treated as continuous. Model fit was assessed through various fit indices including the Yuan-Bentler scaled chi square (Y-B χ2), comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the 90% confidence interval (CI) of the RMSEA. A non-significant χ2 indicates that the model fit the data perfectly. In addition, CFI values above .90 and .95 indicate adequate and good fit, respectively. RMSEA CI values below .05 suggest that good fit cannot be ruled out, whereas RMSEA values above .10 suggest that poor fit cannot be ruled out (Hu & Bentler, 1998). To test whether biological sex moderated the relations between COVID-19 worry and insomnia, a latent variable interaction was tested. This term was retained only if significant.

Next, measurement invariance was conducted to determine whether latent insomnia means could be compared between baseline and the 3-month follow-up. Configural, metric, and then scalar invariance were tested. Following this, the model test command was used to compare latent means between baseline and the 3-month follow-up. In cases in which the model was significantly different from the configural model, a model with partial measurement invariance was tested by freeing factors with the highest modification indices, as allowing these items to load freely should lead to improved model fit (Sorbom, 1989). Estimated scale scores were also computed using item intercepts to provide an approximation of the average insomnia scores over time.

Finally, an SEM was conducted to examine whether COVID-19 worry, safety behaviors, stay-at-home length, depression, and insomnia at baseline predicted 3-month follow-up COVID-19 worry, safety behaviors, and insomnia using a cross-lagged design. Age, sex, and race were also entered into the model as covariates. To test whether biological sex moderated the relations between COVID-19 worry and insomnia, a latent variable interaction was tested. The term was retained only if significant.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Correlations, means, and standard deviations of all variables are provided in Table 2. IDAS item 7, 15, and 49 had skew values exceeding |2| and kurtosis values exceeding |7|, values found to be problematic in simulation studies (Curran et al., 1996). The models were run with and without these items and the results were not substantively different, so these items were included in all models. Finally, items 4–7 of the ISI and all items of the IDAS had 20–25% missing data, consistent with a planned missing data design used for the data and the option for participants to not answer any question they did not want to answer.

Table 2.

Correlations, means, and standard deviations of study variables.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. BL COVID Worry | |||||||||||||

| 2. BL Stock | .58*** | ||||||||||||

| 3. BL Clean | .34*** | .46*** | |||||||||||

| 4. BL Avoid | .17** | .10 | .49*** | ||||||||||

| 5. BL Insomnia | .60*** | .29*** | .01 | −.05 | |||||||||

| 6. M3 Insomnia | .55*** | .24*** | .06 | −.05 | .83*** | ||||||||

| 7. M3 Stock | .61*** | .82*** | .33*** | .07 | .30*** | .25*** | |||||||

| 8. M3 Avoid | .27*** | .19*** | .52*** | .64*** | .05 | .11* | .21*** | ||||||

| 9. Age | −.08 | −.05 | −.06 | .03 | −.13* | −.17** | .04 | .02 | |||||

| 10. Sex | .02 | −.11 | .08 | .03 | .04 | .08 | −.08 | .07 | .08 | ||||

| 11. Race | −.11 | −.28*** | −.09 | .08 | −.12 | −.13 | −.16* | .09 | .12** | .07 | |||

| 12. Dep | .69*** | .31*** | .03 | −.10 | .74*** | .66*** | .37*** | .01 | −.23*** | −.02 | −.12 | ||

| 13. SAH | .05 | −.001 | −.001 | .11 | .03 | −.02 | .07 | .08 | −.01 | .11 | .01 | .02 | |

| Mean (%) | 13.04 | 4.71 | 9.67 | 13.04 | 7.57 | 7.45 | 4.77 | 11.86 | 38.05 | 53.6 | 84.1 | 30.38 | 3.58 |

| SD | 10.09 | 4.00 | 4.35 | 4.03 | 6.59 | 6.45 | 4.21 | 4.44 | 10.64 | 10.71 | 1.44 | ||

Note. BL = Baseline. M3 = 3-month follow-up. Stock = Stockpiling behaviors. Clean = Cleanliness behaviors. Avoid = Avoidance behaviors. Sex was coded as a binary variable (female = 1). Race was coded as a binary variable (white = 1). SAH = Stay at home status. % = % of females for Sex and % of White participants for Race.

= p < .05.

= p < .01.

= p < .001.

Structural equation model between COVID worry, COVID safety behaviors, stay at home length, depression, and insomnia severity at baseline

The SEM including COVID-19 worry, COVID-19 safety behaviors, stay at home length, depression, age, sex, and race as independent variables and insomnia as the dependent variable provided adequate fit to the data (χ2 = 3265.43, df = 1146, p < .001, CFI = .87, TLI = .86, RMSEA = .05, 90% CI [.05, .06], SRMR = .15). There were no significant latent variable interactions; interaction terms were therefore not included for model parsimony. In this model, depression was positively associated with concurrent insomnia severity (β = .70, p < .001). All cross-sectional associations for this model are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Cross-sectional associations between COVID worry, safety behaviors, and insomnia, controlling for Age, Sex, Race, Stay at Home status, and Depression

| Insomnia Severity |

||

|---|---|---|

| Baseline Variables | β | SE |

| Stockpiling behavior | .05 | .05 |

| Cleanliness behavior | −.01 | .05 |

| Avoidance behavior | −.04 | .04 |

| COVID worry | .12 | .08 |

| Depression symptoms | .70*** | .07 |

| Sex (Female = 1) | .03 | .03 |

| Race (White = 1) | −.01 | .03 |

| Age | .04 | .03 |

| Stay at home status | −.04 | .03 |

Note. All associations were entered simultaneously in a single structural equation model.

= p < .05

= p < .01

= p < .001.

Measurement invariance in insomnia severity from baseline to 3-month follow-up

The configural model of insomnia from baseline to 3-month follow-up provided marginal to adequate fit to the data (χ2 = 204.97, df = 69, p < .001, CFI = .94, TLI = .93, RMSEA = .08, 90% CI [.07, .09], SRMR = .05). There was no difference in model fit between this model and the metric invariance model (∆χ2= 5.86, ∆ df = 7, p = .56). The model allowing metric invariance also provided marginal to adequate fit (χ2 = 209.74, df = 76, p < .001, CFI = .94, TLI = .93, RMSEA = .07, 90% CI [.06, .09], SRMR = .05). There was no difference in model fit between the metric invariance model and the scalar invariance model (∆χ2= 2.22, ∆ df = 7, p = .95). Further, the scalar invariance model provided marginal to adequate model fit to the data (χ2 = 216.18, df = 83, p < .001, CFI = .94, TLI = .93, RMSEA = .07, 90% CI [.06, .08], SRMR = .05). Comparing the latent means revealed no significant difference between the latent mean at baseline, standardized at 0 and the latent mean at 3-month follow-up (interceptdiff = −.03, p = .50).

Longitudinal structural equation model between COVID worry, COVID safety behaviors, stay at home length, and insomnia severity

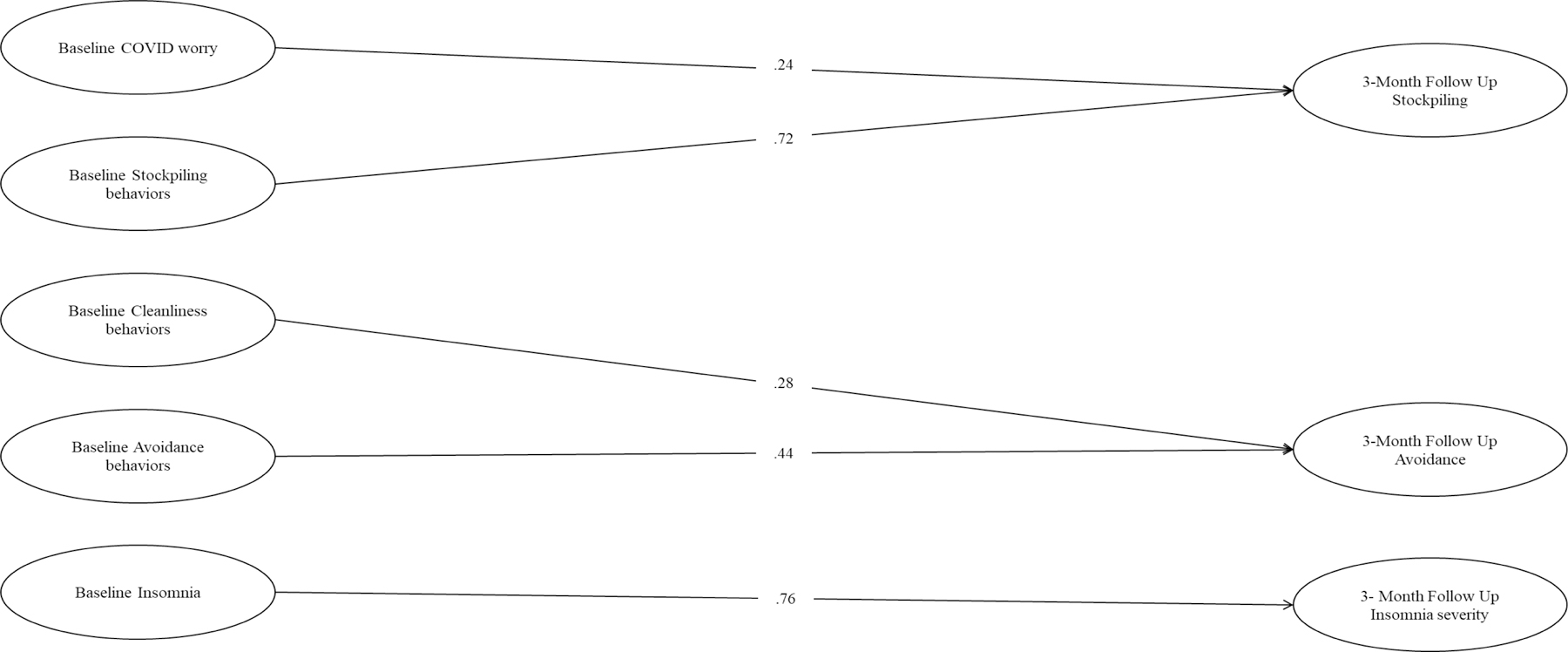

The SEM including baseline COVID-19 worry, COVID-19 safety behaviors, stay at home length, insomnia, and the relevant covariates predicting 3-month follow-up COVID-19 worry, COVID-19 safety behaviors, and insomnia failed to converge. Examination of areas of local strain revealed issues concerning linear dependency involving COVID-19 worry scores and COVID-19 cleanliness behaviors. Removing these factors as outcomes allowed the model to converge; this model provided marginal to adequate fit (χ2 = 3359.78, df = 1912, p < .001, CFI = .89, TLI = .88, RMSEA = .05, 90% CI [.05, .05], SRMR = .08). Again, there were no significant interactions. Allowing a series of residual variances among items from similar scales improved model fit to CFI > .90 without substantively altering the path estimates. Therefore, although the SEM provided only marginal fit to the data, this model was reported. Table 4 contains all standardized model parameters. Baseline insomnia significantly predicted insomnia at 3-month follow-up (β = .70, p < .001). There were no other significant predictors of insomnia. Controlling for the effect of baseline stockpiling (β = .72, p < .001), baseline COVID-19 worry positively predicted 3-month follow-up stockpiling (β = .24, p < .05). Controlling for the effect of baseline avoidance (β = .44, p < .001), baseline cleanliness behaviors were significantly positively associated with 3-month follow-up avoidance behaviors (β = .28, p < .01). There were no other significant associations between any other predictors and avoidance behaviors at 3-month follow up (all p’s > .18). The overall model explained 70.1%, 45.2%, and 67.1% of the variance in stockpiling behaviors at 3-month follow up, avoidance behaviors at 3-month follow up, and insomnia severity at 3-month follow up, respectively. These associations are also displayed graphically in Figure 1.

Table 4.

Structural equation model examining the longitudinal associations between COVID worry, COVID safety behaviors, and insomnia

| M3 Insomnia Severity | M3 Stockpiling behaviors | M3 Avoidance behaviors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Variables | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE |

| Stockpiling behavior | −.06 | .06 | .72*** | .06 | −.04 | .08 |

| Cleanliness behavior | −.06 | .06 | −.08 | .09 | .28** | .09 |

| Avoidance behavior | −.04 | .05 | −.003 | .08 | .44*** | .08 |

| COVID worry | .10 | .12 | .24* | .11 | .16 | .11 |

| Insomnia symptoms | .70*** | .70 | −.08 | .06 | .03 | .09 |

| Depression symptoms | .08 | .07 | .05 | .08 | −.06 | .10 |

| Sex (Female = 1) | .06 | .04 | −.01 | .04 | .02 | .05 |

| Race (White = 1) | −.03 | .04 | .05 | .04 | .09 | .06 |

| Age | −.06 | .04 | .01 | .04 | .01 | .05 |

| Stay at home status | −.02 | .04 | −.02 | .04 | .02 | .05 |

Note. All associations were entered simultaneously in a single structural equation model. M3 = 3 month follow up.

= p < .05

= p < .01

= p < .001.

Figure 1.

Structural equation model examining longitudinal associations between COVID worry, COVID safety behaviors, and insomnia

Note. All associations were entered simultaneously in a single structural equation model. Solid lines represent significant standardized associations. Non-significant associations were excluded for the purposes of clarity. In addition, covariates were excluded as they were not significantly associated with any outcomes.

Discussion

Our primary aim was to identify risk factors of insomnia during the COVID-19 pandemic in two waves of data collection that occurred three months apart. To date, most of the COVID-19 research on insomnia symptoms has been cross-sectional, and our study provided a longitudinal perspective of risk factors and insomnia. Additionally, the role of safety behaviors specific to the COVID-19 crisis has been understudied and, to our knowledge, the relationship between COVID-19-related safety behaviors and insomnia has not been explored.

We found that higher baseline depressive symptoms were associated with more severe insomnia at baseline. This replicates other findings of a concurrent relationship between depression and insomnia in COVID-19 samples (e.g., Voitsidis et al., 2020). The intercorrelation between depression and insomnia suggests treatment for insomnia during COVID-19 would benefit from incorporation of depression treatments. This recommendation is supported by recent work incorporating treatment for comorbid psychiatric disorders during treatment for insomnia (e.g., Jansson-Fröjmark & Norell-Clarke, 2016). Further, given the bidirectional relationship between insomnia and depression, it may be beneficial to prioritize treatment of insomnia and appropriate sleep hygiene in the treatment of depression.

To date, there is limited work investigating the longitudinal relationship between depression and insomnia during the COVID-19 crisis. We found that only baseline insomnia severity predicted insomnia at the 3-month follow-up. This suggests that, although there may be concurrent involvement of depression as a risk factor for insomnia symptoms, depression did not predict insomnia severity at our 3-month follow-up. However, our findings suggest that insomnia symptoms associated with COVID-19 are not transient and thus may develop into more chronic sleep disorders that require intervention. It has been well-documented that insomnia and sleep-related problems may arise due to stressful life events but can outlast the precipitating event (Lavie, 2001; Morin et al., 2020). Sleep plays a fundamental role in maintaining mental and physical health, and treatment of insomnia should be prioritized to minimize potential enduring negative consequences.

We also examined risk factors that are uniquely associated with the COVID-19 pandemic for their relation to insomnia symptoms. Unlike prior studies, we were unable to identify COVID-19 worry (Killgore et al., 2020; Kokou-Kpolou et al., 2020; Voitsidis et al., 2020) as a risk factor of concurrent insomnia severity. This is likely because COVID-19 worry was assessed differently across studies. Voitsidis et al. (2020) and Kokou-Kpolou et al. (2020) did not provide sample items or a description for how COVID-19 worry was assessed, limiting the interpretation of their findings. Killgore et al. (2020) based their COVID-19 worry items on a previous 20 item SARS stress scale (e.g., I feel COVID-19 will spread quickly). Our definition of COVID-19 worry was based on a validated measure that comprehensively examined the challenges related to the COVID-19 crisis across three domains. Thus, this apparent difference in findings can likely be explained by these different definitions of COVID-19-related worry. We also did not find a relationship between sex and insomnia symptoms in our study, although other studies have found higher rates of insomnia for women (Marelli et al., 2020; Rosaria Gualano et al., 2020; Voisidis et al., 2020).

This was the first study, to our knowledge, that has explored COVID-19-related safety behaviors as a risk factor for insomnia. Although COVID-19-related safety behaviors and COVID-19 worry were not related to insomnia, baseline cleanliness and avoidance predicted avoidance behaviors at the 3-month follow-up, and baseline COVID-19 worry and baseline stockpiling predicted stockpiling at the 3-month follow-up. Based on our model, it appears that safety behaviors such as cleanliness and stockpiling have predictive value for future avoidance and stockpiling behaviors, respectfully. This suggests that safety behaviors were stable across our three-month study period, with avoidance predicting later avoidance and stockpiling predicting later stockpiling. Although COVID-19-related safety behaviors were not predictive of insomnia, these preliminary findings are worthy of future study.

There were several limitations that should be noted when considering our findings. First, we were limited to only two points of data collection in the current study, and additional time points may have supplied a better prediction of insomnia symptoms over time. Second, we began data collection several weeks after restrictions were placed across the country in April 2020 and we may have found different results if we assessed the presence of risk factors and insomnia severity earlier in the pandemic. Third, our second time point was in August 2020, when many regions had lessened their public health guidelines, which may have altered the challenges associated with the pandemic. Depression symptoms or COVID-19 worry may have dramatically changed along with changes in public heath guidelines between our two time points. If this is the case, risk factors of insomnia may be dynamic and fluctuate based on the concurrent challenges of the pandemic. It is also important to note that we relied on self-reported symptoms of insomnia using a well-validated scale, but this is not equivalent to a full clinical assessment for insomnia. We were unable to corroborate the psychological symptoms reported by our participants with clinical interview, and there are limitations with relying on self-report measures of psychological constructs, such as the overreporting of symptoms. We also acknowledge that the literature reports gender as a correlate of insomnia, while we reported sex assigned at birth. We recruited through the MTurk system, which has been criticized as being susceptible to “bot” responses (e.g., Pei et al., 2020). To address these concerns, we recruited MTurk participants through CloudResearch (Litman, Robinson, & Abberbock, 2017), which provides additional screening of participants and improves data quality, and we incorporated several recommendations from the literature (Peer et al., 2014; Pei et al., 2020).

Despite these limitations, our findings demonstrate the importance of studying depression and insomnia over time, as there appear to be different cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships between these variables. Future research should investigate how additional time points clarify the relationship between risk factors and insomnia severity during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, we found that insomnia symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic appear to be stable over a three-month period, even with challenges of the pandemic changing over this time. We assessed two specific transdiagnostic risk factors, COVID-19 worry and COVID-19 safety behaviors; these constructs were also stable over the three-month period. Thus, the current study suggests persistent insomnia symptoms, COVID-19 worry, and safety behaviors are associated with COVID-19. Future research should continue to investigate how these relationships change over time as stress accumulates and the challenges associated with the pandemic continue to change.

References

- Alvaro PK, Roberts RM, & Harris JK (2013). A systematic review assessing bidirectionality between sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression. Sleep, 36(7), 1059–1068. 10.5665/sleep.2810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arpaci I, Karataş K, & Baloğlu M (2020). The development and initial tests for the psychometric properties of the COVID-19 Phobia Scale (C19P-S). Personality and Individual Differences, 164, 110108. 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, DSM-5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bastien CH, Vallières A, & Morin CM (2001). Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep medicine, 2(4), 297–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, & James Rubin G (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395, 912–920. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandu VC Marella Y, Panga GS, Pachava S, & Vadapalli Viswanath. (2020). Measuring the impact of COVID-19 on mental health: A scoping reviw of the existing scales. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 42, 421–427. 10.1177/0253717620946439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, West SG, & Finch JF (1996). The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological methods, 1(1), 16. [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa JF, Wadhera RK, Mehtsun WT, Riley K, Phelan J, & Jha AK (2021). Association of race, ethnicity, and community-level factors with COVID-19 cases and deaths across U.S. counties. Healthcare, 9, 100495. 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2020.100495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortier-Brochu É, Beaulieu-Bonneau S, Ivers H, & Morin CM (2012). Insomnia and daytime cognitive performance: A meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 16(1), 83–94. 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Sanguino C, Ausín B, Ángel Castellanos M, Saiz J, López-Gómez A, Ugidos C, & Muñoz M (2020). Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87, 172–176. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, & Bentler PM (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological methods

- Jansson-Fröjmark M & Norell-Clarke A (2016). Cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia in psychiatric disorders. Current Sleep Medicine Reports, 2, 223–240. 10.1007/s40675-016-0055-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore WDS, Cloonan SA, Taylor EC, Fernandez F, Grandner MA, & Dailey NS (2020). Suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of insomnia [Letter to the editor]. Psychiatry Research, 290(113134). 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokou-Kpolou CK, Megalakaki O, Laimou D, & Kousouri M (2020). Insomnia during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown: Prevalence, severity, and associated risk factors in French population [Letter to the editor]. Psychiatry Research, 290(113128). 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyle SD, Morgan K, & Espie CA (2010). Insomnia and health-related quality of life. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 14(1), 69–82. 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauriola M, Carleton RN, Tempesta D, Calanna P, Socci V, Mosca O, Salfi F, Gennaro L.De , & Ferrara M (2019). A correlational analysis of the relationships among intolerance of uncertainty, anxiety sensitivity, subjective sleep quality, and insomnia symptoms. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(3253). 10.3390/ijerph16183253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavie P (2001). Sleep disturbances in the wake of traumatic events. New England Journal of Medicine, 345, 1825–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L, Wang J, Ou-yang X. yong, Miao Q, Chen R, Liang F, Zhang Y, Tang Q, & Wang T (2020). The immediate impact of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak on subjective sleep status. Sleep Medicine, Advanced online publication, 18–24. 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Litman L, Robinson J, & Abberbock T (2017). TurkPrime.com: A versatile crowdsourcing data acquisition platform for the behavioral sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 49(2), 433–442. 10.3758/s13428-016-0727-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marelli S, Castelnuovo A, Somma A, Castronovo V, Mombelli S, Bottoni D, Leitner C, Fossati A, & Ferini-Strambi L (2020). Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on sleep quality in university students and administration staff. Journal of Neurology, Advanced online publication. 10.1007/s00415-020-10056-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McDonald RP (1999). Test Theory: A Unified Treatment. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Morin CM, Carrier J, Bastien C, Godbout R, & Canadian Sleep and Circadian Network. (2020). Sleep and circadian rhythm in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Canadian Journal of Public Health, Advanced online publication. 10.17269/s41997-020-00382-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2017). Mplus User’s Guide. Sixth Edition. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, & Katsaounou P (2020). Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, Advanced online publication. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Patsali ME, Mousa DPV, Papadopoulou EVK, Papadopoulou KKK, Kaparounaki CK, Diakogiannis I, & Fountoulakis KN (2020). University students’ changes in mental health status and determinants of behavior during the COVID-19 lockdown in Greece. Psychiatry Research, 292(113298). 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peer E, Vosgerau J, & Acquisti A (2014). Reputation as a sufficient condition for data quality on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Behavior research methods, 46(4), 1023–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei W, Mayer A, Tu K, & Yue C (2020). Attention Please: Your Attention Check Questions in Survey Studies Can Be Automatically Answered. In Proceedings of The Web Conference 2020 (pp. 1182–1193). [Google Scholar]

- Rhemtulla M, Jia F, Wu W, & Little TD (2014). Planned missing designs to optimize the efficiency of latent growth parameter estimates. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 38(5), 423–434. [Google Scholar]

- Rosaria Gualano M, Lo Moro G, Voglino G, Bert F, & Siliquini R (2020). Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on mental health and sleep disturbances in Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(4779). 10.3390/ijerph17134779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi R, Socci V, Talevi D, Mensi S, Niolu C, Pacitti F, Di Marco A, Rossi A, Siracusano A, & Di Lorenzo G (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown measures impact on mental health among the general population in Italy. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 7–12. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruprecht MM, Wang X, Johnson AK, Xu J, Felt D, Ihenacho S, Stonehouse P, Curry CW, DeBroux C, Costa D, & Phillips G II (2020). Evidence of social and structural COVID-19 disparities by sexual orientation, gender identity, and race/ethnicity in an urban environment. Journal of Urban Health, Advanced online publication. 10.1007/s11524-020-00497-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Schmidt NB, Allan NP, Koscinski B, Mathes B, Eackles K, Accorso C, Allan DM, Potter K, Garey L, Suhr J, Austin M, Zvolensky MJ (2020). COVID-19 Impact Battery: Development and Validation. [Manuscript submitted for publication]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sörbom D (1989). Model modification. Psychometrika, 54(3), 371–384. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S, Landry CA,Paluszek MM, Fergus TA, McKay D, & Asmundson GJG (2020). Development and initial validation of the COVID Stress Scales. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 72, 102232. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas I, & Perlis ML (2020). Insomnia and depression: Clinical associations and possible mechanistic links. Current Opinion in Psychology, 34, 95–99. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voitsidis P, Gliatas I, Bairachtari V, Papadopoulou K, Papageorgiou G, Parlapani E, Syngelakis M, Holeva V, & Diakogiannis I (2020). Insomnia during the COVID-19 pandemic in a Greek population [Letter to the editor]. Psychiatry Research, 289(113076). 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, & Ho RC (2020). Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5). 10.3390/ijerph17051729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhu LY, Ma YF, Bo HX, Deng HB, Cao J, Wang Y, Wang XJ, Xu Y, Lu QD, Wang H, & Wu XJ (2020). Association of insomnia disorder with sociodemographic factors and poor mental health in COVID-19 inpatients in China. Sleep Medicine, 75, 282–286. 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, O’hara MW, Simms LJ, Kotov R, Chmielewski M, McDade-Montez EA, Gamez W, & Stuart S (2007). Development and validation of the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS). Psychological Assessment, 19(3), 253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Yu Z, Xu Y, Liu W, Liu L, & Mao H (2020). Mental status of patients with chronic insomnia in China during COVID-19 epidemic. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, Advanced online publication. 10.1177/0020764020937716 [DOI] [PubMed]