Abstract

Few consistent predictors of differential cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) outcome for anxious youth have been identified, although emerging literature points to youth reward responsiveness as a potential predictor. In a sample of youth ages 7–17 with a primary anxiety disorder (N = 136; Mage = 12.18 years, SDage = 3.12; 70 females; Caucasian n = 108, Black n = 12, Asian n = 4, Hispanic n = 5, other n = 7), the current study examined whether youth reward responsiveness assessed via the Behavioral Inhibition and Behavioral Activation System Scales for children, reward responsiveness subscale, predicted post-treatment (a) anxiety symptom severity, (b) depressive symptom severity, (c) functioning, (d) responder status and (e) number of homework/exposure tasks completed following 16-weeks of CBT, controlling for pre-treatment age, sex, anxiety/depressive symptom severity, and functioning. Moderation analyses examined whether relationships differed by age. Increased reward responsiveness was associated with lower anxiety and depressive symptom severity, higher functioning, and increased likelihood of being a responder, but not homework or exposure completion. Moderation analyses showed that younger, but not older, youth who were more reward responsive completed more exposures. Findings indicate that increased reward responsiveness is a predictor of better CBT outcomes for anxious youth, particularly functional outcomes, and that reward responsiveness may play a different role in exposure completion across development.

Keywords: Youth anxiety, Predictors, Cognitive behavioral therapy, Reward responsiveness, Treatment

1. Introduction

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a well-established treatment for child and adolescent (hereafter referred to as youth) anxiety (Higa-McMillan, Francis, Rith-Najarian, & Chorpita, 2016), achieving response rates of approximately 60% in large randomized controlled trials (e.g., Kendall, Hudson, Gosch, Flannery-Schroeder, & Suveg, 2008; Walkup et al., 2008). To improve CBT response rates and move towards more personalized and precise anxiety treatments, the field has sought to identify predictors (i.e., variables that have a main effect on outcome; Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn, & Agras, 2002), with limited success (for reviews see Compton et al., 2014; Knight, McLellan, Jones, & Hudson, 2014; Nilsen, Eisemann, & Kvernmo, 2013). The majority of such efforts have focused on readily available demographic, symptom severity and family functioning measures collected routinely at baseline. A pivot towards the examination of broader personality traits (Bucher, Suzuki, & Samuel, 2019), with a focus on adaptive strengths that can be built upon during treatment, may be more fruitful in both identifying consistent predictors and ultimately leveraging predictor findings into the development of targeted interventions.

One predictor variable of interest is reward responsiveness (RR). RR is a complex and multifaceted construct often examined in the context of Gray’s (1982) Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory (RST). RST posits that two systems underly approach and avoidance behavior: (1) a behavioral inhibition system (BIS) associated with avoidance behavior and response inhibition and (2) a behavioral activation system (BAS) involved in goal-directed behavior in response to reward cues. RR is one of three hypothesized factors underlying the BAS, although support for the four-factor structure to the BIS/BAS is mixed (e.g., Muris, Meesters, de Kanter, & Timmerman, 2005; Pagliaccio et al., 2016; Yu, Branje, Keijsers, & Meeus, 2011; for support of the four-factor model see Cooper, Gomez, & Aucote, 2007; Kingsbury, Coplan, Weeks, & Rose-Krasnor, 2013). RR encompasses anticipation of and positive response to receipt of rewards, termed “reward valuation” within a Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) framework (Insel et al., 2010). Higher scores on RR have been associated with positive outcomes, including better performance on a behavioral decision task (Franken & Muris, 2005), increased psychological well-being and affect regulation (Taubitz, Pedersen, & Larson, 2015) and decreased internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Taubitz et al., 2015), although positive correlations with social anxiety have also been documented (Kingsbury et al., 2013).

Youth anticipation of and response to reward receipt (i.e., RR) may play an important role in CBT outcomes for youth with anxiety. The behavioral “B” in CBT draws heavily upon reinforcement principles to reward approach behaviors and remove reinforcers of avoidance (i.e., accommodation). To this end, reward use is a common strategy in the treatment of youth anxiety, with up to 98% of community providers using some form of reward when treating anxious youth (Cho et al., 2019). It may be that this strategy is more efficacious for youth who are higher in RR, thus enhancing overall CBT outcomes. To date, the only studies to examine this hypothesis have focused on neurobiological indices of RR shown to underly BAS self-report (e.g., Ide et al., 2020). This emerging body of literature (N = 3) suggests that neurobiological response to receipt of reward during monetary tasks may be associated with differential outcome for youth with primary anxiety disorders, consistent with a parallel set of findings in samples of youth with major depressive disorder (MDD) and comorbid anxiety (Forbes et al., 2010; Schwartz, Kryza-Lacombe, Liuzzi, Weersing, & Wiggins, 2019; for an exception see Barch et al., 2019). One study examined whether reward positivity (RewP), an EEG-derived event-related potential to reward feedback, predicted outcome for youth (N = 27) with a primary diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) or social anxiety disorder (SoP; Kujawa et al., 2019). Results showed that reduced RR (i.e., lower RewP) was a predictor of better treatment response following randomization to either CBT or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) on some outcome measures (i.e., more change in depressive, but not anxious, symptoms); preliminary moderator analyses indicated that this effect was specific to CBT. In another sample of youth (N = 55) with primary GAD or SoP, increased gray matter volume in a brain area associated with reward processes (i.e., left nucleus accumbens) predicted greater decreases in youth anxiety symptoms and responder status following self-selection into either CBT or SSRI (Burkhouse et al., 2019). Finally, a recent study comparing responders and non-responders to both CBT and a supportive-therapy control condition (N = 72) showed that responders were more reward responsive (i.e., greater pre-treatment fMRI-assessed BOLD response to wins during a monetary task in a cluster from subgenual anterior cingulate cortex to nucleus accumbens; Sequeira et al., in press). Taken together, findings from these three studies suggest that neurophysiological and neuroimaging indices of RR may be associated with response to CBT for anxious youth, although the direction of the relationship between reward processes and treatment outcome is unclear (Kujawa et al., 2019; Sequeira et al., in press) and requires further clarification.

Several additional questions warrant exploration. First, it is unclear which post-treatment outcomes are consistently associated with RR across diagnoses. There is some indication that RR is associated with better outcomes (i.e., more post-treatment change) in depressive, but not anxious, symptoms (Kujawa et al., 2019), although results from a study in a sample of youth with MDD and high anxiety comorbidity found the reverse (i.e., higher RR was associated with better outcomes on measures of anxiety, but not depressive, symptoms; Forbes et al., 2010). Responder status has also been categorized using varying pre-determined cutoffs [i.e., ≥ 35% reduction in pediatric anxiety rating scale scores (PARS; Sequeira et al., in press) and > 50% reduction in PARS (Burkhouse et al., 2019)], rather than a measure assessing global response with available inter-rater reliability estimates (i.e., CGI-I; Guy, 1976). Importantly, no studies have gone beyond post-treatment symptom severity or responder status to examine whether RR is associated with post-treatment functioning, despite the particular importance of this outcome measure to youth and caregivers (Swan & Kendall, 2016). Finally, all studies have utilized neurophysiological or neuroimaging indices to assess responsiveness primarily to monetary reward tasks; self-reported RR has not yet been examined as a predictor of anxiety treatment response. It is unclear whether findings from these studies point to RR specifically as a predictor, or if each measure relates to a different dimension of reward processing more broadly (e.g., the nucleus accumbens is involved in various aspects of motivated behavior and not RR specifically), and whether unique measurement properties of the various neurobiological indices examined have differential relationships to self-reported outcomes at post-treatment. Concurrent efforts utilizing more flexible self-report measures tapping RR specifically are needed that may be more ecologically valid than monetary reward tasks. Use of self-report measures will also help to facilitate implementation of personalized treatments in real-world clinics, where access to MRI scanners or electroencephalogram equipment is likely limited and/or cost prohibitive.

Another question is whether RR is associated with treatment outcome broadly, or with engagement in specific treatment components. Hypotheses have been offered to suggest that increased RR is associated with increased motivation to try therapeutic techniques and to work collaboratively with the therapist (Forbes et al., 2010), but these hypotheses have yet to be tested empirically. Two therapeutic strategies that may be particularly linked to RR within the context of CBT for youth anxiety are homework and exposure, both of which are considered critical components of CBT (Higa-McMillan et al., 2016; Hudson & Kendall, 2002; Kendall et al., 2005; Peris et al., 2017) and are used to reduce avoidance of anxiety-provoking stimuli, a key hypothesized mechanism of CBT. In the Coping Cat program (Kendall & Hedtke, 2006), for example, the protocol suggests that therapists use rewards during each session to encourage youth completion of homework and exposure tasks (i.e., tallying completion of homework and exposures in a “Reward Bank” that can be “cashed in” at varying times for prize-shelf rewards or rewards provided by families). Notably, rewards are discussed less frequently in the adolescent-focused C.A.T. project (Kendall, 2002; Kendall, Choudhury, Hudson, & Webb, 2002). Although studies show that adolescence is a period of heightened RR (Galván, 2010; Somerville, Jones, & Casey, 2010), particularly to social rewards (Forbes & Dahl, 2012), it is difficult to integrate immediate social rewards into session. The diminished use of concrete in-session rewards might mitigate the impact of RR on outcomes for adolescents. Thus, enhanced responsiveness to reward may act by increasing willingness to complete both homework and exposure activities in order to receive individualized rewards, likely more so in child-focused compared to adolescent-focused protocols.

This study aimed to clarify the direction of the relationship between RR and CBT outcomes within a sample of youth ages 7–17 with a primary anxiety disorder (N = 136) who completed a full course of Coping Cat/C.A.T. Project. RR was assessed using self-reported measures, rather than neurobiological indices, and a broader range of outcome variables were examined. Three hypotheses were tested. First, it was hypothesized that higher youth self-reported RR would be associated with (a) lower anxiety symptom severity, (b) lower depressive symptom severity, (c) lower functional impairment, and (d) increased likelihood of being categorized as a responder at post-treatment. A range of outcome variables were examined to clarify mixed findings suggesting that RR may be differentially associated with post-treatment depressive and anxiety symptoms, and to determine whether findings extend to (a) real-world functioning in addition to symptom change and (b) to a commonly used measure of treatment response with available inter-rater reliability estimates. Second, to test whether RR is associated with increased engagement in specific treatment components, youth self-reported RR was examined as a predictor of number of homework and exposures completed, given the use of rewards in motivating engagement in these active treatment ingredients (Higa-McMillan et al., 2016; Hudson & Kendall, 2002; Kendall et al., 2005). It was hypothesized that higher RR would be associated with increased number of completed homework and exposure tasks. Third, we hypothesized that age would moderate the relationships examined in the first two hypotheses, such that the relationship between RR and all dependent variables would be stronger for children than for adolescents, as concrete rewards are typically used more frequently in child versus adolescent treatments (Kendall, 2002; Kendall et al., 2002, 2006). This hypothesis was tentative because adolescence can be viewed as a period characterized by hyper-responsiveness to reward (Galván, 2010; Somerville et al., 2010) and thus an argument can be made for the reverse relationship.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

During the data collection period, 184 youth ages 7–17 years and their primary caregivers presented to the Child and Adolescent Anxiety Disorders Clinic (CAADC), an outpatient research clinic at Temple University. Recruitment occurred primarily through community referrals in the greater Philadelphia area. A total of 136 youth-caregiver dyads (Mage = 12.18 years, SD = 3.12; 70 females; Caucasian1 n = 108, Black n = 12, Asian n = 4, Hispanic n = 5, other n = 7) were deemed eligible for participation in treatment following pretreatment assessment and attended at least one session (n = 28 ineligible, n = 20 accepted but never returned for a session following pretreatment assessment). Principal DSM-5 anxiety diagnoses for the 136 dyads included GAD (n = 75), SoP (n = 42), separation anxiety disorder (SAD; n = 8), specific phobia (SP; n = 8), panic disorder (PD; n = 1), agoraphobia (n = 1) and illness anxiety disorder (n = 1).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Diagnostician measures

2.2.1.1. Anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-5 child and parent versions.

(ADIS-5-C/P; Albano & Silverman, 2016). The ADIS-5-C/P is a semi-structured interview for the diagnosis of anxiety and other related youth disorders using diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition criteria (DSM-5; Association, A. P., 2013). The ADIS-5-C/P was administered separately to youth and caregivers at both pre- and post-treatment, and information from both interviews was used to generate composite youth diagnoses based on consensus from the diagnosticians who conducted youth and parent interviews. Although psychometric properties of the most recent version have not been reported, the ADIS-IV-C/P (Silverman, Albano, & Barlow, 1996) has demonstrated convergent and discriminant validity (Wood, Piacentini, Bergman, McCracken, & Barrios, 2002) and retest reliability (Silverman, Saavedra, & Pina, 2001). All diagnosticians completed reliability training prior to administration. A subset of consecutive interviews (N = 20) was presented to the group to calculate inter-rater reliability for youth and parent diagnoses. Inter-rater reliability was high (youth-reported GAD ICC = 0.82, parent-reported GAD ICC = 0.89; youth-reported SoP ICC = 0.91, parent-reported SoP ICC = 0.93; youth-reported SAD ICC = 0.94, parent-reported SAD ICC = 0.93).

2.2.1.2. Children’s global assessment scale.

(CGAS; Shaffer et al., 1983). The CGAS is a single-item scale that asks diagnosticians to rate the youth’s level of general functioning along a scale of 1 (in need of constant supervision to function) to 100 (superior functioning in all areas) using standardized guidelines. The CGAS has showed inter-rater reliability, retest reliability, and discriminant and concurrent validity (Shaffer et al., 1983). Diagnosticians used information gathered during the ADIS-5-C/P to inform CGAS ratings at pre- and post-treatment. Composite CGAS scores were generated based on consensus from the diagnosticians who conducted youth and parent interviews. Composite CGAS ICCs were 0.78 in a sample of sixteen consecutive pre-treatment assessments presented to all diagnosticians.

2.2.1.3. Clinician global impressions-improvement scale.

(CGI-I; Guy, 1976) On the CGI-I, diagnosticians were asked to rate total improvement in youth anxiety along a 7-point scale, with ratings reflecting whether the change was due to treatment. Composite scores were generated based on consensus from both youth and parent diagnosticians. Consistent with previous trials (e.g., Walkup et al., 2008), youth who received a rating of 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved) were considered responders; youth who received a score of 3 (minimally improved) or greater were considered non-responders. In a sample of fifteen consecutive post-treatment assessments, diagnosticians achieved 94.1% inter-rater agreement on identifying responder status.

2.2.2. Child-report measures

2.2.2.1. Multidimensional anxiety scale for children child and parent versions.

(MASC-C; March, Parker, Sullivan, Stallings, & Conners, 1997) The MASC-C is a 39-item youth-report of anxiety symptom frequency over the last two weeks (0 = “never” to 3 = “often”) administered to youth at pre- and post-treatment. To account for item missingness, responses were averaged to create a total score, with higher scores indicating more severe anxiety symptoms. The MASC has demonstrated internal reliability and convergent and divergent validity (March et al., 1997; Villabø, Gere, Torgersen, March, & Kendall, 2012). Internal consistency at pre-treatment was α = 0.89 in the current sample.

2.2.2.2. Behavioral inhibition and behavioral activation system scales for children, reward responsiveness subscale.

(BIS/BAS-C; Muris et al., 2005). The BIS/BAS-C is a 20-item self-report measure of behavioral inhibition and activation adapted from the adult version for use with youth, which was administered at pre-treatment. Youth are asked to indicate how true various statements are about themselves on a scale of 0 (not true) to 3 (very true). Responses to the five items that make up the previously validated reward responsiveness BAS score (“I feel excited and full of energy when I get something that I want,” “When I am doing well at something, I like to keep doing this,” “I get thrilled when good things happen to me,” “I get very excited when I would win a contest” and “I get really excited when I see an opportunity to get something I like”) were averaged to yield a BAS Reward Responsiveness factor scale (BAS), with higher scores indicating greater RR. The BIS/BAS-C has demonstrated meaningful factor structure, satisfactory reliability, and convergent and divergent validity (Kingsbury et al., 2013; Muris et al., 2005; Vervoort et al., 2010). Internal consistency for the reward subscale was α = 0.77 in the current sample.

2.2.2.3. Mood and feelings questionnaire: short version.

(MFQ-C; Costello & Angold, 1988). The MFQ-C/P is a 13-item youth-report of youth depressive symptoms in the past two weeks along a scale of 0 (not true) to 2 (true) administered at pre-treatment and post-treatment. Youth were asked to report on how they had been feeling and acting along a scale of 0 (not true) to 2 (true). For the current study, responses were averaged to create a total score, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms. The MFQ-C has shown internal reliability (Kuo, Stoep, & Stewart, 2005) and content, convergent and concurrent validity (Thabrew, Stasiak, Bavin, Frampton, & Merry, 2018). Internal consistency at pre-treatment was α = 0.87 in the current sample.

2.3. Procedures

All study procedures were approved by the Temple University Institutional Review Board. Youth and their caregivers were eligible to receive treatment at the CAADC if they (a) were between the ages of 7–17, (b) met criteria for a principal diagnosis of a DSM-5 anxiety disorder, and (c) were English-speaking and able to provide informed consent/assent. Eligibility followed multiple gating: caregivers completed a preliminary phone screen with trained study staff to determine whether youth symptoms indicated potential presence of a primary anxiety disorder and then, when caregivers endorsed elevated youth anxiety symptoms, an in-person pretreatment assessment was completed. This assessment included (a) collection of assent/consent, (b) a semi-structured diagnostic assessment administered by reliable diagnosticians separately to caregiver and youth, and (3) completion of a battery of self-report measures (e.g., MASC-C, MFQ-C, BAS). Measures for the current study were added into the battery of self-report and parent-report measures collected routinely at the research clinic. Youth diagnoses and ratings of functional impairment (CGAS) were determined by diagnosticians based on composite information from both interviews.

Eligible youth completed 16 weeks of CBT with advanced doctoral student therapists trained to fidelity. Therapists followed the Coping Cat protocol (Kendall & Hedtke, 2006) for children and the C.A.T. Project protocol (Kendall, 2002; Kendall et al., 2002) for adolescents. A subset of youth received a modified version of treatment targeting parental accommodation, although outcomes were not significantly different for these treatment formats (Kagan et al., Under Review). Treatment focused on (a) psychoeducation and coping skill development (first phase of treatment) and (b) completion of in-vivo graduated exposure tasks (second phase of treatment). Homework was assigned after each session encouraging youth to (a) practice coping skills discussed in session through a series of exercises outlined in youth workbooks (first phase of treatment) and (b) complete at-home exposure tasks (second phase of treatment). After each session, therapists documented homework compliance (assessed via observed completion of tasks in treatment workbooks during the first phase of treatment and youth self-report of completed exposures during the second phase of treatment) and number of imaginal and in-vivo exposures completed in session. Sessions were primarily child-centered, although two caregiver-only sessions were held during the first phase of treatment and brief check-ins were conducted with caregivers at the end of each session.

After 16 sessions of treatment, youth and caregivers completed the same semi-structured diagnostic assessment and a similar battery of self-report measures (e.g., MASC-C, MFQ-C) to those administered at pre-treatment. Diagnosticians used composite information gathered during both interviews to complete scales assessing treatment response (CGI-I) and post-treatment functioning (CGAS).

2.4. Data analytic plan

2.4.1. Outcome

All analyses were completed in MPlus version 8.5. Three hierarchical regressions and one logistic regression examined the degree to which youth baseline RR (BAS Reward Responsiveness scale) predicted (a) youth post-treatment anxiety symptoms (MASC-C; Model 1), (b) youth post-treatment depressive symptoms (MFQ-C; Model 2) (c) youth post-treatment functioning (CGAS; Model 3) and (d) binary responder status (CGI-I; Model 4). In all models, youth baseline age (assessed continuously) and sex were entered at level 1, given developmental changes in RR (Galván, 2010; Somerville et al., 2010) and the potential differential association between RR and treatment outcome across sexes (Boger et al., 2014; Galván, 2010; Somerville et al., 2010); youth baseline depressive symptoms (MFQ-C), functioning (CGAS) and anxiety symptoms (MASC-C) were entered at level 2; youth RR (BAS) was entered at level 3.

2.4.2. Homework and exposure

Therapists provided data on the (a) number of homework assignments completed (HW) and (b) number of exposure tasks completed (EXP). At each session, therapists documented whether the youth had completed her/his homework task at home (yes = 1, no = 0). This variable was averaged across child-focused sessions to create the HW variable. Therapists also reported on the number of in-vivo and imaginal exposures completed during each session targeting either (a) separation, (b) social, (c) generalized or (d) specific fears. Of note, exposures for the two individuals in the sample with PD and agoraphobia were included in these groupings. The number of in-vivo and imaginal exposures were summed across these domains to calculate the total number of exposures completed during each session, starting at session 10 when the exposure phase of treatment began. These numbers were averaged across sessions to create the EXP variable. The same hierarchical regressions outlined above were run to predict to HW (Model 5) and EXP (Model 6).

2.4.3. Moderation

RR and all covariates were mean-centered. An interaction term was calculated between age and the centered RR variable and entered into step 4 of regression models predicting all outcome variables and HW and EXP. Following Aiken, West, and Reno (1991), simple slopes were graphed for significant interactions.

3. Results

3.1. Missingness

All reported analyses relied on Mplus. Mplus allowed for use of all observations in each model and informed model estimates equivalently based on covariates used as missing data correlates, which was akin to imputation. Formal multiple imputation with 25 datasets was used for binary outcomes (CGI-I). To further probe missingness, little MCAR’s test and predictors of attrition (24% of the sample) were examined. Results of Little’s MCAR test suggested that all predictor variables included in the models were missing completely at random, χ2(15) = 16.04, p = 0.38. In addition, a binary yes/no adherence variable was created to indicate whether eligible youth completed all 16 sessions. A series of logistic regressions were conducted to examine whether any baseline predictor variable (i.e., age, sex, MFQ-C, CGAS, MASC-C, BAS) predicted treatment completion; none were significant. With regards to missingness on individual measures, in line with previous work (e.g., Palitz et al., 2019) youth who were missing more than 33% of data on a measure were excluded from analyses; for youth who had < 33% missing data, averages were calculated from the items that had responses.

3.2. Assumption testing

Descriptive information and correlations for all variables are presented in Table 1. Model assumptions were examined in ordinary least squares analyses. All plots of studentized residuals against predictors showed random scatter, indicating no non-linear relationships between dependent variables and predictors. Constant studentized residual bands were observed with no evidence of heteroscedasticity. No evidence of multicollinearity was found (all r < 0.8 and VIF < 10). Shapiro-Wilk (SW) tests were significant for three models [MFQ-C: SW = 0.95, p = 0.001; HW: SW = 0.92, p < 0.001; EXP: SW = 0.94, p = 0.001]. However, histograms and P-P plots showed adequate symmetry of residuals and skew fell within ±2 (MFQ-C skew = 0.97; HW: skew= −0.89; EXP: skew = 0.96; Gravetter, Wallnau, Forzano, & Witnauer, 2020). No consistently influential outliers were identified across studentized deletion residuals, leverage, Cook’s D, and DFBETA values.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, Ranges and Correlations Among Study Variables.

| Sex | Age | Pre MFQ | Pre CGAS | Pre MASC | BAS | Post MFQ | Post CGAS | Post MASC | CGI-I | HW | EXP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | 51% female | 12.18 | 0.50 | 53.47 | 1.41 | 2.08 | 0.35 | 64.51 | 0.95 | 0.70 | 0.77 | 1.76 |

| (SD) | – | 3.12 | 0.42 | 7.54 | 0.46 | 0.69 | 0.36 | 12.23 | 0.54 | 0.46 | 0.24 | 0.79 |

| Min | – | 7.01 | 0.00 | 36 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.43 |

| Max | – | 17.86 | 1.62 | 72 | 2.56 | 3.00 | 1.69 | 98 | 2.18 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 4.14 |

| Skew | – | 0.07 | 0.81 | 0.35 | −0.41 | −0.77 | 1.14 | 0.27 | 0.18 | −0.88 | −0.91 | 0.99 |

| Sex | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Age | 0.13 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Pre MFQ | 0.17* | 0.28** | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Pre CGAS | 0.01 | −0.14 | −0.30** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Pre MASC | 0.20* | 0.06 | 0.48** | −0.25** | 1.00 | |||||||

| BAS | 0.17* | −0.14 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Post MFQ | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.45** | −0.28** | 0.32** | −0.23* | 1.00 | |||||

| Post CGAS | 0.09 | 0.03 | −0.06 | 0.32** | −0.19 | 0.29** | −0.42** | 1.00 | ||||

| Post MASC | 0.13 | −0.04 | 0.24* | −0.29** | 0.42** | −0.11 | 0.56** | −0.56** | 1.00 | |||

| CGI-I | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.18 | −0.13 | 0.31** | −0.25* | 0.55** | −0.40** | 1.00 | ||

| HW | 0.19 | −0.14 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.23 | −0.20 | 0.36** | −0.14 | 0.30* | 1.00 | |

| EXP | 0.08 | −0.15 | −0.05 | 0.05 | 0.17 | 0.16 | −0.09 | 0.25* | −0.07 | 0.32** | 0.23* | 1.00 |

Note:

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01.

Pre MFQ = baseline Mood and Feelings Questionnaire, short version, child report. Pre CGAS = baseline Children’s Global Assessment Scale. Pre MASC = baseline Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children, child report. BAS = Behavioral Inhibition and Behavioral Activation System Scales for children, reward responsiveness subscale, child report. Post MFQ = post-treatment Mood and Feelings Questionnaire, short version, child report. Post CGAS = post-treatment Children’s Global Assessment Scale. Post MASC = post-treatment Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children, child report. CGI-I = Clinician Global Impressions-Improvement Scale. HW = average number of homework assignments completed. EXP = average number of exposure tasks completed.

3.3. Analyses

3.3.1. Model 1 (MASC-C)

The first model examined RR as predictor of post-treatment anxiety symptoms. As presented in Table 2, the final model accounted for 24% of the variability in post-treatment anxiety scores, with the inclusion of RR accounting for an additional 4% of outcome variance, Wald χ2(1) = 5.09, p = 0.02, ΔR2 = 0.04. More severe pre-treatment anxiety [b = 0.45, SE = 0.12, z = 3.75, p < 0.001] and lower RR [b = −0.16, SE = 0.07, z = −2.26, p = 0.02] were significant predictors of more severe anxiety at post-treatment.

Table 2.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression of Youth Post-Treatment Anxiety (MASC-C; Model 1).

| b | SE | z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step One | ||||

| Age | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.68 | 0.50 |

| Sex | 0.15 | 0.11 | 1.40 | 0.16 |

| R2 = 0.02 | p = 0.45 | |||

| Step Two | ||||

| Age | −0.02 | 0.02 | −1.12 | 0.26 |

| Sex | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.48 | 0.63 |

| Pre MFQ | 0.00 | 0.14 | −0.00 | 1.00 |

| Pre CGAS | −0.02 | 0.01 | −2.13 | 0.03 |

| Pre MASC | 0.39 | 0.12 | 3.28 | 0.00 |

| R2 = 0.20 | p = 0.003 |

Wald χ2(3) = 24.62

ΔR2 = 0.18 |

p<0.001 | |

| Step Three | ||||

| Age | −0.02 | 0.02 | −1.40 | 0.16 |

| Sex | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.66 | 0.51 |

| Pre MFQ | −0.02 | 0.14 | −0.13 | 0.89 |

| Pre CGAS | −0.01 | 0.01 | −1.99 | 0.05 |

| Pre MASC | 0.45 | 0.12 | 3.75 | 0.00 |

| BAS | −0.16 | 0.07 | −2.26 | 0.02 |

| R2 = 0.24 | p = 0.001 |

Wald χ2(1) = 5.09

ΔR2 = 0.04 |

p = 0.02 | |

Note: Pre MFQ = baseline Mood and Feelings Questionnaire, short version, child report. Pre CGAS = baseline Children’s Global Assessment Scale. Pre MASC = baseline Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children, child report. BAS = Behavioral Inhibition and Behavioral Activation System Scales for children, reward responsiveness subscale, child report.

3.3.2. Model 2 (MFQ-C)

The second model examined RR as predictor of post-treatment depressive symptoms. As presented in Table 3, the final model accounted for 27% of the variability in post-treatment depressive symptom scores, with the inclusion of RR accounting for an additional 6% of outcome variance, Wald χ2(1) = 7.58, p = 0.01, ΔR2 = 0.06. More severe pre-treatment depressive symptoms [b = 0.29, SE = 0.10, z = 2.99, p = 0.003] and lower RR [b = −0.13, SE = 0.05, z = −2.75, p = 0.01] were significant predictors of more severe depressive symptoms at post-treatment.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression of Youth Post-Treatment Depression (MFQ-C; Model 2).

| b | SE | z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step One | ||||

| Age | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.75 | 0.46 |

| Sex | 0.08 | 0.07 | 1.04 | 0.30 |

| R2 = 0.02 | p = 0.48 | |||

| Step Two | ||||

| Age | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.17 | 0.86 |

| Sex | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.28 | 0.78 |

| Pre MFQ | 0.30 | 0.10 | 3.10 | 0.00 |

| Pre CGAS | −0.01 | 0.01 | −1.58 | 0.11 |

| Pre MASC | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.73 | 0.47 |

| R2 = 0.22 | p = 0.003 |

Wald χ2(3) = 25.70

ΔR2 = 0.20 |

p<0.001 | |

| Step Three | ||||

| Age | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.51 | 0.61 |

| Sex | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.49 | 0.62 |

| Pre MFQ | 0.29 | 0.10 | 2.99 | 0.00 |

| Pre CGAS | −0.01 | 0.01 | −1.41 | 0.16 |

| Pre MASC | 0.11 | 0.08 | 1.32 | 0.19 |

| BAS | −0.13 | 0.05 | −2.75 | 0.01 |

| R2 = 0.27 | p<0.001 |

Wald χ2(1) = 7.58

ΔR2 = 0.06 |

p = 0.01 | |

Note: Pre MFQ = baseline Mood and Feelings Questionnaire, short version, child report. Pre CGAS = baseline Children’s Global Assessment Scale. Pre MASC = baseline Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children, child report. BAS = Behavioral Inhibition and Behavioral Activation System Scales for children, reward responsiveness subscale, child report.

3.3.3. Model 3 (CGAS)

The third model examined RR as predictor of post-treatment functional impairment. As presented in Table 4, the final model accounted for 26% of the variability in functioning, with the inclusion of RR accounting for an additional 11% of outcome variance, Wald χ2(1) = 13.84, p < 0.001, ΔR2 = 0.11. Increased baseline functioning [b = 0.50, SE = 0.16, z = 3.23, p = 0.001], less severe pre-treatment anxiety [b = −6.44, SE = 2.72, z = −2.37, p = 0.02] and higher RR [b = 6.08, SE = 1.63, z = 3.72, p < 0.001] were significant predictors of increased functioning at post-treatment (Table 4).

Table 4.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression of Youth Post-Treatment Functioning (CGAS; Model 3).

| b | SE | z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step One | ||||

| Age | 0.13 | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.74 |

| Sex | 2.13 | 2.37 | 0.90 | 0.37 |

| R2 = 0.01 | p = 0.61 | |||

| Step Two | ||||

| Age | 0.23 | 0.36 | 0.64 | 0.52 |

| Sex | 2.93 | 2.26 | 1.30 | 0.20 |

| Pre MFQ | 2.84 | 3.45 | 0.82 | 0.41 |

| Pre CGAS | 0.54 | 0.16 | 3.37 | 0.00 |

| Pre MASC | −4.34 | 2.80 | −1.55 | 0.12 |

| R2 = 0.16 | p = 0.02 |

Wald χ2(3) = 16.17

ΔR2 = 0.15 |

p = 0.001 | |

| Step Three | ||||

| Age | 0.40 | 0.35 | 1.12 | 0.26 |

| Sex | 2.33 | 2.18 | 1.07 | 0.29 |

| Pre MFQ | 3.54 | 3.36 | 1.05 | 0.29 |

| Pre CGAS | 0.50 | 0.16 | 3.23 | 0.00 |

| Pre MASC | −6.44 | 2.72 | −2.37 | 0.02 |

| BAS | 6.07 | 1.63 | 3.72 | 0.00 |

| R2 = 0.26 | p = 0.001 |

Wald χ2(1) = 13.84 ΔR2 = 0.11 |

p<0.001 | |

Note: Pre MFQ = baseline Mood and Feelings Questionnaire, short version, child report. Pre CGAS = baseline Children’s Global Assessment Scale. Pre MASC = baseline Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children, child report. BAS = Behavioral Inhibition and Behavioral Activation System Scales for children, reward responsiveness subscale, child report.

3.3.4. Model 4 (CGI-I)

The fourth model examined RR as predictor of binary responder status. As presented in Table 5, the final model accounted for 38% of the variance in CGI-I scores, with the inclusion of RR accounting for an additional 19% of outcome variance, Wald χ2(1) = 10.28, p < 0.001, ΔR2 = 0.19. Increased baseline functioning [b = 0.508, SE = 0.04, z = 1.98, p = 0.05], less severe pre-treatment anxiety [b = −1.60, SE = 0.72, z = −2.21, p = 0.03] and higher RR [b = 1.43, SE = 0.45, z = 3.21, p = 0.001] were significant predictors of responder status. For any one unit increase in RR, there was a 4.17-fold increase in the odds of responding to treatment (CI: 1.74 10.01).

Table 5.

Logistic Regression of Responder Status (CGI-I; Model 4).

| b | SE | OR | CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step One | ||||

| Age | 1.06 | 0.94 | 1.06 | (0.94–1.20) |

| Sex | 1.87 | 0.75 | 1.87 | (0.75–4.67) |

| R2 = 0.05 | p = 0.25 | |||

| Step Two | ||||

| Age | 1.06 | 0.93 | 1.06 | (0.93–1.21) |

| Sex | 2.13 | 0.78 | 2.13 | (0.78–5.83) |

| Pre MFQ | 1.8 | 0.45 | 1.80 | (0.45–7.10) |

| Pre CGAS | 1.08 | 1.01 | 1.08 | (1.01–1.15) |

| Pre MASC | 0.41 | 0.12 | 0.41 | (0.12–1.36) |

| R2 = 0.19 | p = 0.04 |

Wald χ2(3) = 6.61

ΔR2 = 0.14 |

p = 0.09 | |

| Step Three | ||||

| Age | 1.11 | 0.95 | 1.11 | (0.95–1.30) |

| Sex | 2.19 | 0.66 | 2.19 | (0.66–7.25) |

| Pre MFQ | 2.49 | 0.48 | 2.49 | (0.48–12.89) |

| Pre CGAS | 1.08 | 1.00 | 1.08 | (1.00–1.16) |

| Pre MASC | 0.2 | 0.05 | 0.20 | (0.05–0.84) |

| BAS | 4.17 | 1.74 | 4.17 | (1.74–10.01) |

| R2 = 0.38 | p<0.001 |

Wald χ2(1) = 10.28

ΔR2 = 0.19 |

p = 0.001 | |

Note: Pre MFQ = baseline Mood and Feelings Questionnaire, short version, child report. Pre CGAS = baseline Children’s Global Assessment Scale. Pre MASC = baseline Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children, child report. BAS = Behavioral Inhibition and Behavioral Activation System Scales for children, reward responsiveness subscale, child report.

3.3.5. Models 5 (HW) and 6 (EXP)

The fifth and sixth models examined RR as predictor of number of homework and exposure tasks completed throughout treatment. The first steps of Model 5 and 6 did not account for a significant amount of the variance in homework or exposure completion, and the inclusion of additional terms in steps 2 and 3 did not significantly increase the percentage of variance accounted for in either variable. No significant predictors of homework or exposure completion were identified.

3.3.6. Moderation

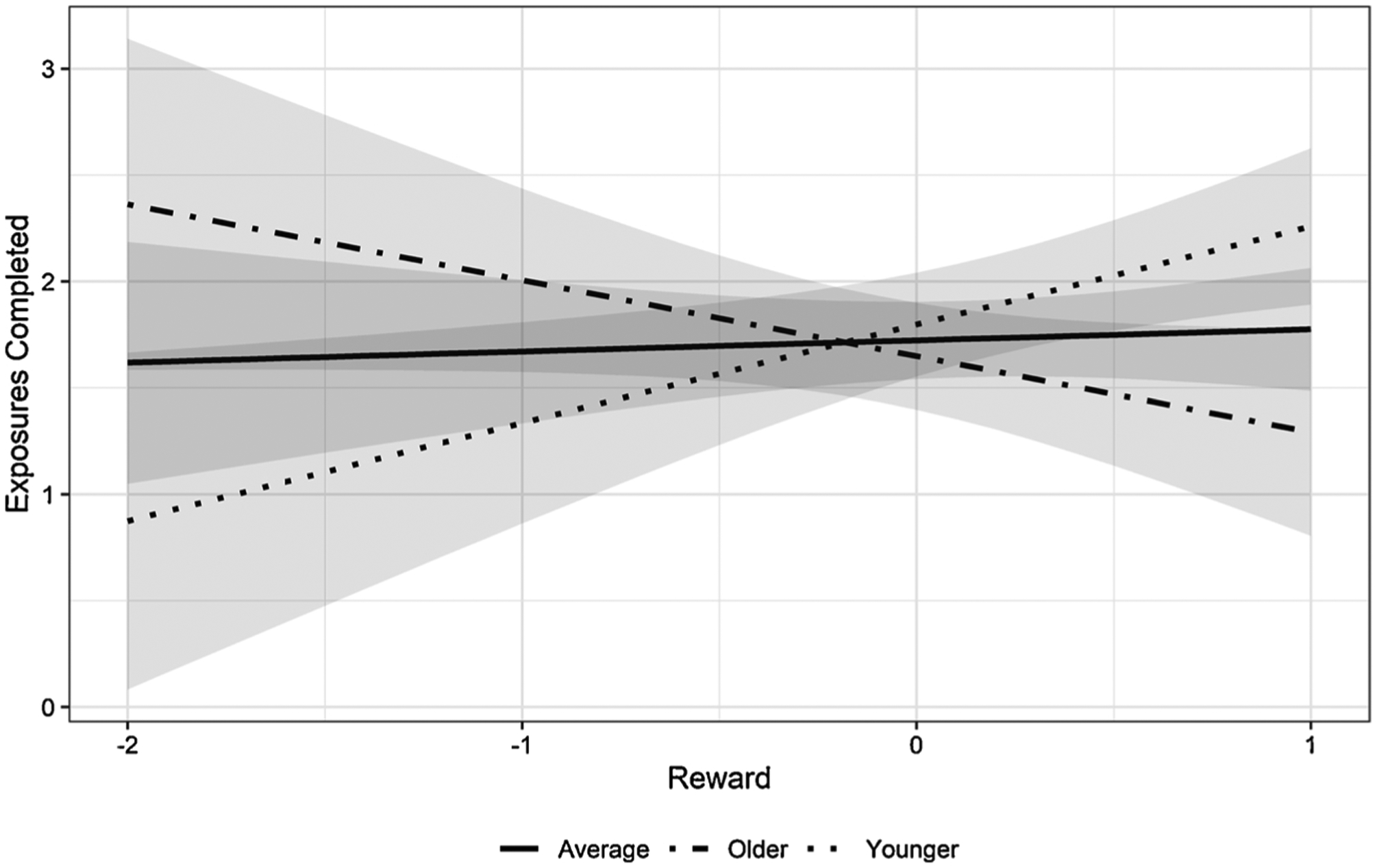

Finally, age was examined as a moderator of the relationship between RR and each dependent variable (anxiety, depressive symptoms, functioning, responder status, and homework and exposure completion). A comparison of models with and without the interaction term indicated that the full interaction effect was statistically significant only for exposure completion (Model 6), Wald χ2(1) = 9.33, p = 0.002, ΔR2 = 0.09; b = −0.14, SE = 0.04, z = −3.05, p = 0.002. The interaction effect is displayed in Fig. 1. For youth one standard deviation (SD) younger than the mean age, increased sensitivity to reward was associated with completion of more exposures, b = 0.46, SE = 0.18, z = 2.62, p = 0.01. For youth one SD higher than the mean age, reward sensitivity was not associated with increased exposure completion, b = −0.36, SE = 0.20, z = −1.82, p = 0.07.

Fig. 1.

Interactive Effect of Age on Reward Responsiveness.

Note: Older youth were 1 SD above the average age; younger youth were 1 SD below the average age.

4. Discussion

RR was found to be a significant factor in CBT outcomes for youth anxiety. Consistent with hypotheses, higher youth self-reported RR was significantly associated with (a) lower anxiety symptom severity, (b) lower depressive symptom severity, (c) lower functional impairment, and (d) responder status, above and beyond youth baseline age, sex, anxiety/depressive symptom severity, and functioning. Inconsistent with hypotheses, RR was not associated with homework/exposure completion, and developmental status did not moderate the relationship between RR and most outcome variables, except number of exposures completed. Younger youth (1 SD below mean) who were more reward responsive completed more exposures; there was no significant relationship between RR and exposure completion for older youth (1 SD above mean). Thus, it appears that the relationship between RR and treatment outcomes holds broadly across age, but with differences for exposure use.

Study findings add to an emerging body of literature indicating that RR is a meaningful predictor variable for outcomes associated with youth treatments broadly (Schwartz et al., 2019), including CBT (Kujawa et al., 2019, Burkhouse et al., 2019; Forbes & Dahl, 2012 Sequeira et al., in press), and suggest that increased RR may be associated with both lower post-treatment anxious and depressive symptoms (Forbes et al., 2010; Kujawa et al., 2019) for youth with primary anxiety disorders. Results extend upon previous findings by showing that increased RR is also a predictor of lower post-treatment functional impairment and a widely used measure of responder status. In fact, RR was more strongly associated with these measures than post-treatment symptom severity, with RR accounting for an additional 11% of the variance in post-treatment functioning and a 4.17-fold increase in the likelihood of being a responder. This suggests that RR may be a particularly relevant factor in predicting more global outcomes (i.e., real-world functional impairment and broad responder status), which are arguably more meaningful outcome measures for youth and their caregivers (Swan and Kendall, 2016), although future more adequately powered studies should consider use of contemporary integrative modeling to explicitly test the relative strengths of the relationships between RR and each outcome variable examined.

Results also further probed how RR might be associated with post-treatment outcomes. Although rewards may be viewed as motivation for youth to complete homework and exposure tasks, it does not appear that RR was linked specifically to increased completion of these tasks, which was inconsistent with previous hypotheses (Forbes et al., 2010). In addition, although differential responsiveness to reward from childhood to adolescence has been documented (Galván, 2010; Somerville et al., 2010), the current results broadly suggest that age does not moderate the relationship between RR and treatment outcome. That said, age was meaningful in that younger youth who were more responsive to rewards engaged in more exposures, whereas RR was not associated with number of exposures completed for older youth. This may be due to heavier emphasis on reward use in child- versus adolescent-focused protocols (Kendall, 2002; Kendall et al., 2002; Kendall et al., 2006). The type of rewards typically used in treatment may also be a factor to consider in interpreting these findings. Adolescents may be more motivated by receipt of social rewards (Forbes & Dahl, 2012), but rewards used in treatment are typically material (e.g., toys from the prize shelf, food), perhaps due to difficulty associated with generating meaningful in-session social rewards for peer-focused adolescents. It is possible that type of reward may be important to account for in future analyses and to consider in future personalized treatment development (i.e., inclusion of more social-focused rewards for adolescent clients). It is also possible that the role of caregivers may need to be taken into account, particularly for caregivers who due to youth treatment refusal take a more heavy-handed approach to facilitate youth treatment involvement.

Findings should be considered in light of study limitations. Importantly, 79% of the present sample identified as Caucasian, limiting external validity of study findings. Tests of the Minorities’ Diminished Return theory (MDR; Assari, 2018a,b) have found higher RR in Black compared to White youth and that race moderates the relationship between RR and both youth age and parent education (Assari, 2020; Assari, Boyce, Akhlaghipour, Bazargan, & Caldwell, 2020). In line with MDR, findings suggest that the negative impacts of segregation, racism and discrimination experienced by Black youth likely extend to reward processing and thus generalizability of current study findings should not be assumed. Second, youth were not randomized to different treatment arms, so conclusions about the specificity of the relationship between RR and CBT outcome rather than treatment more broadly are tentative. Other issues of measurement warrant attention. Specifically, youth RR and homework and exposure completion were assessed via self-report. Other self-reported measures of RR should be considered in future studies, as the four-factor structure of the BIS/BAS has not always been upheld (e.g., Murris et al., 2005; Pagliaccio et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2011) and other conceptual problems with RST have been noted (see Van den Berg, Franken, & Muris, 2010). Additionally, although self-report measures may be more feasible for implementation in real-world clinics and may assess RR more broadly than monetary reward tasks, use of other easy to implement objective measures (e.g., an adapted probabilistic reward task for youth, Pizzagalli, Jahn, & O’Shea, 2005; a social iowa gambling task, Case & Olino, 2020) tapping various aspects of reward processing in conjunction with self-report is advised in future studies. In addition, number of homework assignments and exposure tasks completed does not necessarily correlate with intensity of tasks and should not be interpreted as such. For example, a single exposure task may have been completed during a full session and achieved the same habituation or mastery-learning experience as multiple in-session exposures. It is also important to consider that although reward use is recommended at every session in the Coping Cat and C.A.T. Project protocols and discussed specifically when the “R” step (“Results and Rewards”) of the Fear Plan is reviewed (Kendall and Hedtke, 2006), data were not available on how individual therapists used rewards in treatment (i.e., frequency of reward administration, specific rewards used, reliance on this strategy more broadly). Finally, a more nuanced examination of RR may be of interest. For example, RR as assessed by the BAS may be associated more with reward valuation, but not tap other aspects of reward processing, including reward anticipation, initial response to reward, reward satiation or reward learning (Insel et al., 2010). Findings may also have been driven more broadly by motivational processes, which have overlapping, but distinct, neural underpinnings to RR (Kim, 2013).

Although meaningful predictors of differential outcome have been difficult to identify (Compton et al., 2014; Knight et al., 2014; Nilsen et al., 2013), the present findings indicate that RR may be a predictor of CBT response. Taken together with other findings, the results may help to facilitate development of personalized intervention. For example, findings from the current study suggest that anxious youth who have low RR may respond less optimally to traditional reward-laden CBT. Other interventions may be appropriate for inclusion in CBT protocols or as a stand-alone treatment for individuals with low RR, including finding other ways beyond rewards to enhance motivation via introduction of a motivation manipulation (Pegg & Kujawa, 2020) or a motivation enhancement Unified Protocol module (Ellard, Fairholme, Boisseau, Farchione, & Barlow, 2010) before beginning treatment. If RR is indicative of positive valence system dysfunction more broadly, then youth low in RR may respond more optimally to a novel positive affect treatment (Craske et al., 2019). Finally, Burkhouse et al. (2016) found that lower RR was associated with better CBT response among adults with comorbid depression and anxiety, but not anxiety alone; perhaps youth with low RR might fare better in CBT focused on depressive symptoms. Findings also suggest for clinicians that more focused attention on reward use in treatment (i.e., selecting rewards particularly salient to youth, ensuring consistent use of rewards in session) might help increase outcomes, particularly for younger youth. Thus, continued work examining RR may lend itself to more precise treatments.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [F31MH123038].

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

Philip C. Kendall receives royalties, and his spouse has employment, related to publications associated with the treatment of anxiety in youth. Other authors had no disclosures to report.

Sample demographics were reported in line with explicit survey text to best capture participant responses, rather than using American Psychological Association’s bias-free language guidelines.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG, & Reno RR (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Albano A, & Silverman W (2016). Anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-5, child version. Child and parent interview schedules. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Assari S (2020). Age-related decline in children’s reward sensitivity: Blacks’ diminished returns. Research in Health Science, 5(3), 112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assari S (2018a). Unequal gain of equal resources across racial groups. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 7(1), 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assari S (2018b). Health disparities due to diminished return among black Americans: Public policy solutions. Social Issues and Policy Review, 12(1), 112–145. [Google Scholar]

- Assari S, Boyce S, Akhlaghipour G, Bazargan M, & Caldwell CH (2020). Reward responsiveness in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study: African Americans’ diminished returns of parental education. Brain Sciences, 10(6), 391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association, A. P. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barch DM, Whalen D, Gilbert K, Kelly D, Kappenman ES, Hajcak G, … Luby JL (2019). Neural indicators of anhedonia: Predictors and mechanisms of treatment change in a randomized clinical trial in early childhood depression. Biological Psychiatry, 85(10), 863–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Boger KD, Auerbach RP, Pechtel P, Busch AB, Greenfield SF, & Pizzagalli DA (2014). Co-occurring depressive and substance use disorders in adolescents: An examination of reward responsiveness during treatment. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 24(2), 109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucher MA, Suzuki T, & Samuel DB (2019). A meta-analytic review of personality traits and their associations with mental health treatment outcomes. Clinical Psychology Review, 70, 51–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhouse KL, Kujawa A, Kennedy AE, Shankman SA, Langenecker SA, Phan KL, … Klumpp H (2016). Neural reactivity to reward as a predictor of cognitive behavioral therapy response in anxiety and depression. Depression and Anxiety, 33(4), 281–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhouse KL, Jimmy J, Defelice N, Klumpp H, Ajilore O, Hosseini B, & Phan KL (2019). Nucleus accumbens volume as a predictor of anxiety symptom improvement following CBT and SSRI treatment in two independent samples. Neuropsychopharmacology, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case JA, & Olino TM (2020). Approach and avoidance patterns in reward learning across domains: An initial examination of the Social Iowa Gambling Task. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 125, Article 103547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho E, Wood PK, Taylor EK, Hausman EM, Andrews JH, & Hawley KM (2019). Evidence-based treatment strategies in youth mental health services: Results from a national survey of providers. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 46(1), 71–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton S,N, Peris T,S, Almirall D, Birmaher B, … Rynn MA (2014). Predictors and moderators of treatment response in childhood anxiety disorders: Results from the CAMS trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(2), 212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper A, Gomez R, & Aucote H (2007). The behavioural inhibition system and behavioural approach system (BIS/BAS) scales: Measurement and structural invariance across adults and adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(2), 295–305. [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, & Angold A (1988). Scales to assess child and adolescent depression: Checklists, screens, and nets. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 27(6), 726–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Meuret AE, Ritz T, Treanor M, Dour H, & Rosenfield D (2019). Positive affect treatment for depression and anxiety: A randomized clinical trial for a core feature of anhedonia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 87(5), 457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellard KK, Fairholme CP, Boisseau CL, Farchione TJ, & Barlow DH (2010). Unified protocol for the transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Protocol development and initial outcome data. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 17(1), 88–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes EE, & Dahl RE (2012). Research review: altered reward function in adolescent depression: what, when and how? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(1), 3–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes EE, Olino TM, Ryan ND, Birmaher B, Axelson D, Moyles DL, … Dahl RE (2010). Reward-related brain function as a predictor of treatment response in adolescents with major depressive disorder. Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience, 10(1), 107–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franken IH, & Muris P (2005). Individual differences in decision-making. Personality and Individual Differences, 39(5), 991–998. [Google Scholar]

- Galván A (2010). Adolescent development of the reward system. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 4, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravetter FJ, Wallnau LB, Forzano L-AB, & Witnauer JE (2020). Essentials of statistics for the behavioral sciences. Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA (1982). Pŕecis of the neuropsychology of anxiety: An enquiry into the functions of the septo-hippocampal system. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 5(3), 469–484. [Google Scholar]

- Guy W (1976). ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology. US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service. [Google Scholar]

- Higa-McMillan CK, Francis SE, Rith-Najarian L, & Chorpita BF (2016). Evidence base update: 50 years of research on treatment for child and adolescent anxiety. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology : the Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53, 45(2), 91–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JL, & Kendall PC (2002). Showing you can do it: Homework in therapy for children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(5), 525–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide JS, Li HT, Chen Y, Le TM, Li CS, Zhornitsky S, … Li CSR (2020). Gray matter volumetric correlates of behavioral activation and inhibition system traits in children: An exploratory voxel-based morphometry study of the ABCD project data. Neuroimage, 220, Article 117085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, Heinssen R, Pine DS, Quinn K, & Wang P (2010). Research domain criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. Academic Psychiatry Association. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan ER, Frank Hannah E., Palitz Sophie A., Kendall Philip C. (Under Review). Targeting Parental Accommodation in the Treatment of Youth with Anxiety: A Comparison of Two Cognitive Behavioral Treatments.

- Kendall PC (2002). The CAT project workbook: For the cognitive behavioral treatment of anxious adolescents. Workbook Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall P, & Hedtke K (2006). The coping cat program workbook. Ardmore, PA: Workbook Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall P, Choudhury M, Hudson J, & Webb A (2002). The CAT project therapist manual. Ardmore, PA: Workbook. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Robin JA, Hedtke KA, Suveg C, Flannery-Schroeder E, & Gosch E (2005). Considering CBT with anxious youth? Think exposures. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 12(1), 136–148. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Hudson J, Gosch E, Flannery-Schroeder E, & Suveg C (2008). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disordered youth: A randomized clinical trial evaluating child and family modalities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 282–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SI (2013). Neuroscientific model of motivational process. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsbury A, Coplan RJ, Weeks M, & Rose-Krasnor L (2013). Covering all the BAS’s: A closer look at the links between BIS, BAS, and socio-emotional functioning in childhood. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(5), 521–526. [Google Scholar]

- Knight A, McLellan L, Jones M, & Hudson J (2014). Pre-treatment predictors of outcome in childhood anxiety disorders: A systematic review. Psychopathology Review, 1(1), 77–129. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, & Agras WS (2002). Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59(10), 877–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujawa A, Burkhouse KL, Karich SR, Fitzgerald KD, Monk CS, & Phan KL (2019). Reduced reward responsiveness predicts change in depressive symptoms in anxious children and adolescents following treatment. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 29(5), 378–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo ES, Stoep AV, & Stewart DG (2005). Using the short mood and feelings questionnaire to detect depression in detained adolescents. Assessment, 12(4), 374–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Parker JD, Sullivan K, Stallings P, & Conners CK (1997). The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): Factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36 (4), 554–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Meesters C, de Kanter E, & Timmerman PE (2005). Behavioural inhibition and behavioural activation system scales for children: Relationships with Eysenck’s personality traits and psychopathological symptoms. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(4), 831–841. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen TS, Eisemann M, & Kvernmo S (2013). Predictors and moderators of outcome in child and adolescent anxiety and depression: A systematic review of psychological treatment studies. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 22(2), 69–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagliaccio D, Luking KR, Anokhin AP, Gotlib IH, Hayden EP, Olino TM, … Barch DM (2016). Revising the BIS/BAS Scale to study development: Measurement invariance and normative effects of age and sex from childhood through adulthood. Psychological Assessment, 28(4), 429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palitz SA, Rifkin LS, Norris LA, Knepley M, Fleischer NJ, Steinberg L, … Kendall PC (2019). But what will the results be?: Learning to tolerate uncertainty is associated with treatment-produced gains. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 68, Article 102146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegg S, & Kujawa A (2020). The effects of a brief motivation manipulation on reward responsiveness: A multi-method study with implications for depression. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 150, 100–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peris TS, Caporino NE, O’Rourke S, Kendall PC, Walkup JT, Albano AM, & Ginsburg GS (2017). Therapist-reported features of exposure tasks that predict differential treatment outcomes for youth with anxiety. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(12), 1043–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzagalli DA, Jahn AL, & O’Shea JP (2005). Toward an objective characterization of an anhedonic phenotype: A signal-detection approach. Biological Psychiatry, 57(4), 319–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz KT, Kryza-Lacombe M, Liuzzi MT, Weersing VR, & Wiggins JL (2019). Social and non-social reward: A preliminary examination of clinical improvement and neural reactivity in adolescents treated with behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 13, 177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sequeira SL, Silk JS, Ladouceur CD, Hanson JL, Ryan ND, Morgan JK … Forbes EE (in press) Function in neural reward circuitry is associated with psychological treatment response in youth with anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, Ambrosini P, Fisher P, Bird H, … Aluwahlia S (1983). A children’s global assessment scale (CGAS). Archives of General Psychiatry, 40(11), 1228–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman W, Albano A, & Barlow D (1996). Manual for the ADIS-IV-C/P. New York, NY: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Saavedra LM, & Pina AA (2001). Test-retest reliability of anxiety symptoms and diagnoses with the Anxiety Disorders Interview schedule for DSM-IV: Child and parent versions. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(8), 937–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville LH, Jones RM, & Casey B (2010). A time of change: Behavioral and neural correlates of adolescent sensitivity to appetitive and aversive environmental cues. Brain and Cognition, 72(1), 124–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan AJ, & Kendall PC (2016). Fear and missing out: Youth anxiety and functional outcomes. Clinical Psychology Science and Practice, 23(4), 417–435. [Google Scholar]

- Taubitz LE, Pedersen WS, & Larson CL (2015). BAS reward Responsiveness: A unique predictor of positive psychological functioning. Personality and Individual Differences, 80, 107–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thabrew H, Stasiak K, Bavin LM, Frampton C, & Merry S (2018). Validation of the mood and feelings questionnaire (MFQ) and Short Mood and feelings questionnaire (SMFQ) in New Zealand help-seeking adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 27(3), e1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg I, Franken IH, & Muris P (2010). A new scale for measuring reward responsiveness. Frontiers in Psychology, 1, 239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vervoort L, Wolters LH, Hogendoorn SM, De Haan E, Boer F, & Prins PJ (2010). Sensitivity of Gray’s behavioral inhibition system in clinically anxious and non-anxious children and adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 48(5), 629–633. [Google Scholar]

- Villabø M, Gere M, Torgersen S, March JS, & Kendall PC (2012). Diagnostic efficiency of the child and parent versions of the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 41(1), 75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walkup JT, Albano AM, Piacentini J, Birmaher B, Compton SN, Sherrill JT, … Kendall PC (2008). Cognitive behavioral therapy, sertraline, or a combination in childhood anxiety. The New England Journal of Medicine, 359(26), 2753–2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, Piacentini JC, Bergman RL, McCracken J, & Barrios V (2002). Concurrent validity of the anxiety disorders section of the anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV: Child and parent versions. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 31(3), 335–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu R, Branje SJ, Keijsers L, & Meeus WH (2011). Psychometric characteristics of Carver and White’s BIS/BAS scales in Dutch adolescents and their mothers. Journal of Personality Assessment, 93(5), 500–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]