The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has major economic consequences across the USA.1 Along with heightened risk for severe COVID-19,2 older adults have less digital access which may be a barrier to mobilizing supports including grocery delivery.3,4 While people with lower incomes and from racial and ethnic minoritized groups have faced high levels of material hardship due to COVID-19,1 little is known about the experience of older adults. We aim to assess the prevalence and risk factors for material hardship and food insecurity among older adults in the USA.

METHODS

We used the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally representative cohort study of aging, to identify community-dwelling adults age ≥51. Beginning June 11th 2020, a COVID-19 subsample was randomly selected for telephone interviews. While HRS continues to collect data, this study reflects that available on November 12, 2020, with a response rate of 62%. Material hardship due to COVID-19 was defined as follows: receiving money or help paying bills from family/friends; missing payments on rent or mortgage, credit cards or other debt, utilities, insurance, or medical bills; not having enough money to buy food; or other material hardship. Food insecurity was defined as not having enough money to buy food and/or having difficulty buying food despite having money. Therefore, not having enough money to buy food was an indicator of both material hardship and food insecurity. Sociodemographic, household, and health characteristics were derived from the HRS. We assessed the prevalence of material hardship and food insecurity in the population and across sociodemographic, household, and health categories. Proportions were adjusted to account for survey design and response rate. This study was approved by the Mount Sinai Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

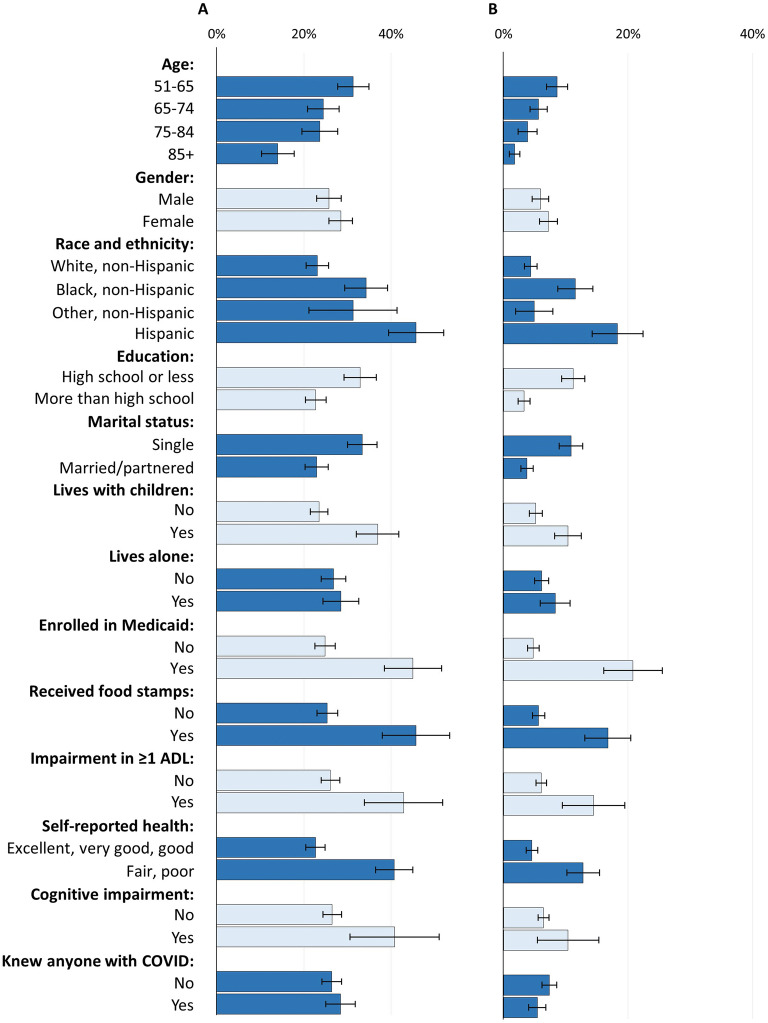

Of 3053 community-dwelling older adults, nearly half were >65 years, with 10.7% Black and 10.6% Hispanic (Table 1). Material hardships (reported by 27.2%) and food insecurity (reported by 6.6%) followed similar demographic patterns (Fig. 1). Material hardships decreased with age, and were more common among Hispanics (45.7% [39.4–52.0%]) and Black non-Hispanics (34.3% [29.4–39.2%] vs. White non-Hispanics (23.1% [20.5–25.7%]). Those who were unmarried vs. married, lived with children vs. not, and received Medicaid or food stamps vs. not were more likely to experience material hardships. Greater material hardship was reported by those with impairments in activities of daily living (ADLs) (42.9% [33.9–51.9%]) vs. without (26.1% [24.0–28.2%)], cognitive impairment (40.8% [30.6–51.0%]) vs. without (26.5% [24.3–28.6%]), and fair/poor health (40.7% [36.5–45.0%]) vs. good/excellent (22.7% [20.4–24.9%]).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Those in COVID-19 Survey (N=3053)

| Characteristic | % |

|---|---|

| Demographics and health | |

| Age: | |

| 51–65 | 48.5% |

| 65–74 | 31.2% |

| 75–84 | 15.4% |

| > 85 | 4.8% |

| Female | 52.9% |

| Race | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 73.1% |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 10.7% |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 5.7% |

| Hispanic | 10.6% |

| More than HS education | 58.5% |

| Married | 59.3% |

| Any children | 90.6% |

| Lives with children | 27.6% |

| Lives alone | 25.5% |

| Medicaid | 11.4% |

| Received food stamps in last year | 9.7% |

| ADL impairment | 6.5% |

| IADL impairment | 9.9% |

| Fair/poor health | 25.1% |

| Cognitive impairment1 | 4.1% |

| COVID-19 experience | |

| Probably or definitely had COVID-19 | 2.0% |

| Known someone who had COVID-19 | 38.5% |

| Known someone who died of COVID-19 | 16.9% |

| Experienced any of the below material hardships due to COVID-19: | 27.2% |

| Receiving financial help such as money or others paying bills | 21.1% |

| Missed rent or mortgage payments | 2.8% |

| Missed payments on credit cards or other debt | 4.1% |

| Missed utility, insurance, other bill payments | 3.3% |

| Did not have money for food | 6.6% |

| Trouble buying food despite having money for it | 15.7% |

| Food insecurity: trouble accessing food, either due not having money or other trouble buying2 | 20.8% |

Data source: Health and Retirement Study (HRS), 2020. Survey conducted beginning June, 2020. Proportions adjusted to account for survey design and weighting. ADLs, activities of daily living (walking indoors, toileting, dressing, eating, transferring, bathing); IADLS, instrumental activities of daily living (meal preparation, grocery shopping, making phone calls, taking medications, managing finances). 1Cognitive impairment determined through self-report of memory problems and/or dementia. 2Not having money for food and trouble buying food even though had money were not mutually exclusive, as individuals may have experienced these at different times during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nationally representative of the community dwelling (non-nursing home) population age 51 and older in 2020

Figure 1.

Prevalence of material hardship and food insecurity due to COVID-19 across sociodemographic and health groups (N=3053). Legend: Data source: Health and Retirement Study (HRS), 2020. Survey conducted beginning June, 2020. Proportions adjusted to account for survey design and weighting. ADLs, activities of daily living (walking indoors, toileting, dressing, eating, transferring, bathing). Cognitive impairment determined through self-report of memory problems and/or dementia. Nationally representative of the community dwelling (non-nursing home) population age 51 and older in 2020.

DISCUSSION

This nationally representative survey demonstrates that 1 in 3 older adults reported material hardship as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. We identified both racial and socioeconomic disparities in hardship during COVID-19 as well as heightened vulnerability for older adults in poor health and with functional or cognitive impairments.

The high prevalence of food insecurity among those receiving food stamps is notable, given that nutrition benefits were increased during the pandemic.5 This may be because the assistance was insufficient, or because of limitations in how food stamps may be used (such as through online grocery shopping or paying for delivery fees). The lower prevalence of hardship for the oldest in the cohort may indicate their relative resilience and the protections of social security and Medicare.

Although dementia is likely underreported in this study, those with cognitive and functional (ADL) impairments have higher levels of material hardship, indicating a need for targeted supports for this population. This is consistent with prior work demonstrating heightened food insecurity among those with chronic conditions.6 The measure of material hardship was not validated, and so further assessments of it are needed. Further work is needed to assess the interplay and additive effects among factors.

While the response rate for this early data release is lower than the usual HRS survey, detailed information is known about non-responders, allowing survey weights to partially account for bias in non-response. This study examines the effects of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, and it will be important for future research to measure how access to supports such as food stamps has changed prior to, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

These findings signal an urgent need for targeted supports to older adults at highest risk for food and material hardships, such as those from minoritized groups and in poor health.

Funding

Dr. Ankuda is funded by the National Institute on Aging K76AG064427 and the American Federation for Aging Research. Dr. Kelley is funded by the National Institute on Aging K24AG062785 and R01AG054540. Dr. Byhoff is funded by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities K23MD015267.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Parker K, Minkin R, Bennett J. Economic Fallout from COVID-19 Continues to Hit Lower-Income Americans the Hardest. Pew Center Report: September 20, 2020. https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2020/09/24/economic-fallout-from-covid-19-continues-to-hit-lower-income-americans-the-hardest/. Accessed Dec 3, 2020.

- 2.Gupta S, Hayek SS, Wang W, Chan L, Mathews KS, Melamed ML, Brenner SK, Leonberg-Yoo A, Schenck EJ, Radbel J, Reiser J, Bansal A, Srivastava A, Zhou Y, Sutherland A, Green A, Shehata AM, Goyal N, Vijayan A, JCQ V, Shaefi S, Parikh CR, Arunthamakun J, Athavale AM, Friedman AN, SAP S, Kibbelaar ZA, Abu Omar S, Admon AJ, Donnelly JP, Gershengorn HB, Hernán MA, Semler MW, Leaf DE. STOP-COVID Investigators. Factors Associated with Death in Critically Ill Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 in the US. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(11):1–12. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts ET, Mehrotra A. Assessment of Disparities in Digital Access Among Medicare Beneficiaries and Implications for Telemedicine. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(10):1386–1389. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rummo PE, Bragg MA, Yi SS. Supporting Equitable Food Access During National Emergencies—The Promise of Online Grocery Shopping and Food Delivery Services. JAMA Health Forum. Published online March 27, 2020. 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2020.0365 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Dunn CG, Kenney E, Fleischhacker SE, Bleich SN. Feeding Low-Income Children During the Covid-19 Pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):e40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2005638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jih J, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Seligman HK, Boscardin WJ, Nguyen TT, Ritchie CS. Chronic Disease Burden Predicts Food Insecurity Among Older Adults. Public Health Nutrition. 2018;21(9):1737–1742. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017004062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]