Abstract

Background

Given increasing numbers of people experiencing transitions in health insurance due to declines in employer-sponsored insurance and changes in health policy, the understanding and application of health insurance terms and concepts (health insurance literacy) may be important for navigating use of health care. The study objective was to systematically review evidence on the relationship between health insurance literacy and health care utilization.

Methods

Medline, SCOPUS, Web of Science, CINAHL, PsychInfo, Cochrane Library, and reference lists of published literature were searched in August 2019. Quantitative, qualitative, and intervention studies that assessed the association of health insurance literacy as the exposure and health care utilization as the outcome were identified, without language or date restrictions. Outcomes were independently assessed by 2–3 reviewers.

Results

Twenty-one studies including a total of 62,416 subjects met inclusion criteria: three interventional trials, two mixed-methods studies, and sixteen cross-sectional studies. Ten of thirteen preventive care studies suggested that higher health insurance literacy was associated with greater utilization of primary care and other preventive services. Eight of nine studies of care avoidance demonstrated that individuals with lower health insurance literacy were more likely to delay or avoid care. A few studies had mixed results regarding the utilization of emergency department, inpatient, and surgical care.

Discussion

The emerging literature in this area suggests that health insurance literacy is an important factor that can enable effective utilization of health care, including primary care and preventive services. However, the literature is limited by a paucity of studies using validated tools that broadly measure health insurance literacy (rather than testing knowledge of specific covered services). Improving health insurance literacy of the general public and increasing plain language communication of health insurance plan features at the point of health care navigation may encourage more effective and cost-conscious utilization.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-021-06819-0.

Key Words: health insurance literacy, health care utilization, delay or avoidance of care, medication adherence

INTRODUCTION

In the wake of insurance coverage reforms and recent marked declines in employment and employer-sponsored insurance associated with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, US families are undergoing transitions in health insurance at a rapid pace. Such transitions may include losing health insurance coverage or switching plans from employer-sponsored insurance to Medicaid, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplace, or other types of coverage. The diversity of plans available to the American consumer underscores the importance of assessing individuals’ understanding and navigation of plan features. Health insurance literacy (HIL) encompasses the knowledge of health insurance terms and the application of health insurance concepts. Numerous survey-based studies have found that HIL is low in the general population.1,2 Moreover, lower HIL is more prevalent amongst several populations with a high risk of unmet medical needs: those of lower socioeconomic status,3 racial/ethnic minorities,4 and older adults.5

Low HIL is problematic insofar as it could lead to ineffective and inefficient use of the health care system, resulting in financial and/or medical harm. Early work in the field of HIL has shown that individuals with lower HIL had greater difficulty choosing insurance plans than those with higher HIL,6 whereas those with higher HIL were found to be more capable of making choices on coverage provisions based on their personal values and medical history.7 Moreover, custom-made decision aids to guide plan selection that provided plan education, individualized cost estimates, and assessment of priorities led to increased HIL, decision self-efficacy, and confidence in plan selection when compared to unaided navigation of the health insurance Marketplace.8 However, understanding which insurance plan to purchase does not necessarily ensure effective utilization of the health care system. As one aspect of HIL is understanding how to apply insurance concepts, utilization is an important outcome measure to study.

Longstanding work in the related field of health literacy (which is distinct from HIL in its attention to knowledge about health, rather than health insurance) has demonstrated associations with health care utilization. A 2011 systematic review including 96 primary studies found that low health literacy was associated with suboptimal utilization: specifically, low health literacy was associated with greater emergency department utilization; more hospitalizations; lower utilization of preventative health care; and decreased adherence to prescription medications.9,10

HIL is a distinct form of literacy and self-efficacy from health literacy that may affect health care utilization in different and important ways. With its focus on patients’ understanding of health insurance and health care, HIL encompasses functional knowledge of health plans’ benefits, cost-sharing, and other details that could empower appropriate use of health care. Thus, studying the association between HIL and utilization can elucidate how (or whether) this functional knowledge impacts utilization. Given the increasing number of changes to health insurance and health care in the current era, the time is ripe to review the literature on HIL as an important factor in how, when, and why people utilize health care.

METHODS

We conducted a systematic review of the literature assessing the association between HIL and health care utilization. A search and extraction protocol was developed using guidelines from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)11 and made publicly available via PROSPERO prior to study initiation.12

Literature Search

The primary search was conducted in Medline (OVID). To develop the search strategy, the team examined relevant articles identified through team expertise and conducted exploratory searches on HIL and health care utilization in Medline. Since a MeSH term for “health insurance literacy” does not exist, the search combined literacy-related MeSH terms (e.g., health knowledge, attitudes, practice, health literacy) and keywords (e.g., confidence, attitude, understanding, ability, self-efficacy) with health insurance MeSH terms and keywords, to broadly capture the HIL literature. Additional database searches were translations of the core Medline search and included the following databases: Scopus (Elsevier), Web of Science (Clarivate), PsycINFO (EBSCOhost), CINAHL Complete (EBSCOhost), and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Wiley). Searches were run from database inception to the date of search: August 16, 2019. See Appendix 1 for further details of search terms. Reference lists of included documents were reviewed, and citation tracking of included documents took place in Scopus. Grey literature searching included conference proceedings. There were no restrictions on dates, language, country of origin, or patient population; intended subgroup analyses included the US vs. non-US and adult vs. pediatric populations.

Study Selection

The article titles and abstracts returned by the search were reviewed by three authors (BFY, JEL, MRF) in duplicate to determine if the studies appeared to contain any data on the association between HIL and health care utilization. Inclusion criteria were based on a broad definition of HIL: the knowledge and/or application of health insurance concepts, including laws, regulations, or policies governing health insurance. Any assessments of HIL were included, from validated measures such as the Health Insurance Literacy Measure (HILM)13 to author-created measures developed for specific studies. We also included measures of health literacy broadly so that full-text articles could be screened for potential secondary assessments of HIL.

Utilization was broadly defined as the use of and access to services for the purpose of preventing and curing health problems, promoting health and well-being, or obtaining information about one’s health.14 All measures of health care utilization that met this definition were included (e.g., outpatient visits, emergency department visits, hospitalizations, avoidance of care, medication use/adherence, vaccinations). We did not include measures of health outcomes, health expenditures, quality of care, or medication management (as opposed to use). Disagreements regarding study inclusion or exclusion were resolved through discussion with a fourth reviewer (RT).

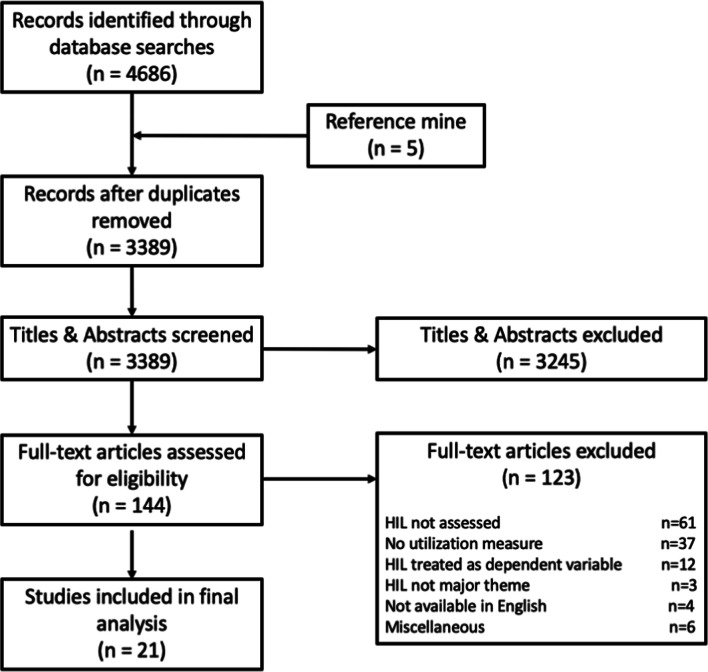

Full texts of the articles meeting the above selection criteria were uploaded into the DistillerSR15 online tool and reviewed by two authors (BFY, MRF) to determine if the studies met the inclusion criteria and reported on the appropriate exposure (HIL) and outcome (utilization). At this phase of review (see Fig. 1), qualitative studies (e.g., reports of focus groups) in which the relationship between HIL and utilization did not comprise a key theme or major finding were excluded. Studies in which HIL was treated as the outcome and not the exposure by the authors were excluded, as this was the reverse of the study objective. After full-text review, studies with measures of general health literacy (e.g., REALM, TOFHLA, NVS) but not including HIL were excluded. Studies with self-reported utilization were included, but studies that only assessed the intention or future plans to utilize health care were excluded. Disagreements regarding study inclusion at this phase of the review were resolved through discussion with a third or fourth reviewer (AMS, RT).

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram. Flow diagram of literature search, abstract screen, full article assessment for exclusion and inclusion criteria with most common reasons for exclusion detailed. Abbreviations: HIL, health insurance literacy.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data were extracted by two authors (BFY, MRF) using DistillerSR. Extracted variables included year, study type, data source, population (including sample size), country, how HIL was assessed, what type of utilization was assessed, how utilization was assessed, and the magnitude and significance of findings (Table 1). Studies were classified as a trial if there was an intervention with prospective randomization. HIL and health care utilization were considered significantly associated if p < 0.05 or if the confidence interval of the comparison measure did not include the null value. Studies that did not find a statistically significant association were included. Risk of bias review and quality assessment was conducted using principles outlined in the Appraisal Tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS), finding that the included studies met between 75 and 95% of the twenty indicators of quality (Appendix 2).16

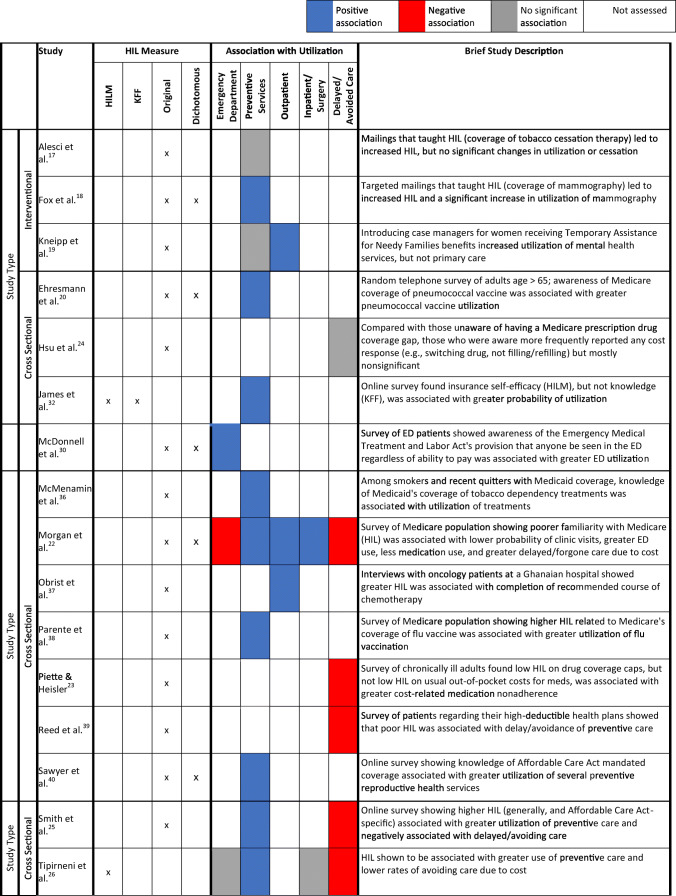

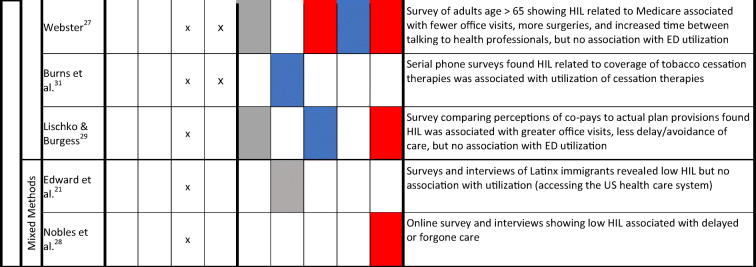

Table 1.

Patterns of Association Between Health Insurance Literacy and Utilization

Abbreviations: HIL, health insurance literacy; ED, emergency department; HILM, Health Insurance Literacy Measure, a subjective measure of confidence in health insurance decision-making; KFF, Kaiser Family Foundation objective measure of health insurance knowledge

The 21 included studies are sorted by study type. The method of assessing HIL is denoted by Xs in the relevant cells. Dichotomous measures include assessments of HIL that asked a yes/no question about objective HIL knowledge or grouped respondents into high HIL/low HIL groups for analysis. Utilization measures were grouped into 5 categories: ED; preventive services (including primary care outpatient visits and use of specific services such as cancer screening, vaccinations, and tobacco cessation treatment); outpatient care (including subspecialty clinic visits and urgent visits); inpatient and surgical care, which were grouped together because of their higher costs and a paucity of studies; and delayed or avoidance of care

Legend: Blue = higher levels of HIL associated with increased utilization of the outcome measure; Red = higher levels of HIL associated with decreased utilization of the outcome measure (i.e., HIL is associated with fewer delays or avoidance of care, including medication use); Grey = no significant association between HIL and the outcome measure; White = association between HIL and the outcome measure was not assessed

Results

Study Characteristics

The initial search returned 3389 deduplicated results (Fig. 1). After reviewing the abstracts, 144 studies advanced to full-text review. Twenty-one studies ultimately met study criteria and were included in the final analysis. Of the twenty-one studies included in the final analysis (with publication dates from 2001 to 2019), three were prospective trials in which HIL was incorporated into an intervention, either as a direct objective of the study (e.g., sending participants reminders that a certain health care service is covered without any out-of-pocket costs)17,18 or as a consequence of the intervention (e.g., assigning case managers to high-risk patients to help them navigate their health insurance and health care).19 Table 1 provides a color-coded summary of results, stratified by the utilization measures; Table 2 provides more granular details on each study, including year, population, and a detailed summary of results. Two of the three interventional trials showed that increased HIL led to increased health care utilization. The remaining eighteen studies were cross-sectional analyses using surveys and/or semi-structured interviews. Most (18 of 21) of the included studies had multivariable adjustment incorporated into their analysis. Only one study was conducted outside of the USA (in Ghana),37 and only one study included a pediatric population,30 obviating the ability to perform subgroup analyses by country of origin or age of patient population. No purely qualitative studies met the final study inclusion criteria because their discussions of the relationship between HIL and utilization were ancillary, rather than constituting a major theme of the study. The most common reason for exclusion was that the study assessed health literacy, rather than HIL, or that it did not report utilization as an outcome (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Detailed Description of Included Studies

| Study | Year | Study type; variable adjustment in analysis | Population (including N) | HIL assessment | Type of utilization outcome | Mode of utilization assessment | Study findings | Magnitude of association/effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alesci et al.17 | 2004 | Intervention; multivariable adjustment | Smokers in Minnesota insurance plan (n=1930) | Self-reported knowledge of insurance plan’s smoking cessation benefit and 3-item questionnaire about benefit | Tobacco cessation treatment; tobacco cessation | Survey | -Knowledge of plan benefit greater in control vs. intervention group with targeted mailed communication but no significant differences in tobacco benefit utilization between two groups | Bupropion treatment in past 12 months 23.1% in control vs. 24.6% in intervention group (p=0.92); any nicotine replacement treatment use in past 12 months 25.9% vs. 26.9% in control vs. intervention group (p=0.26) |

| Fox et al.18 | 2001 | Intervention; multivariable regression | Women age > 65 in southern California (n=917, 922) | Knowledge that screening mammograms are covered by Medicare | Mammography in last 2 years | Survey | -Mailing to increase knowledge that Medicare pays for breast cancer screening led to increased mammogram use among minorities who received the intervention relative to control group. | -Black women (OR 1.97) |

| -Hispanic women (OR 2.33) | ||||||||

| -White women (OR 1.04) | ||||||||

| -However, the intervention did not increase screening amongst white women | ||||||||

| Kneipp et al.19 | 2011 | Intervention; multivariable regression | Women with chronic health conditions receiving TANF benefits in Florida (n=285) | 20-item questionnaire related to Medicaid coverage | New mental health visit, primary care routine, or preventive visit | Survey | -Subjects receiving intervention with public health nurse case manager who taught HIL and other topics were more likely to have a new mental health visit but not more likely to have preventive care visit | -New mental health visit (OR 1.92) |

| -Preventative care visit (OR 1.50) | ||||||||

| Ehresmann et al.20 | 2001 | Cross-sectional, quantitative; multivariable regression | Adults age > 65 in Minnesota (n=353) | Survey assessing awareness of Medicare coverage for pneumococcal vaccine | Pneumococcal vaccination | Survey | -Awareness that Medicare covers pneumococcal vaccine associated with receipt of pneumococcal vaccine | OR 5.1 |

| Hsu et al.24 | 2008 | Cross-sectional, quantitative; multivariable regression | Medicare Advantage beneficiaries (age>65) in Kaiser Permanente system, California (n=1040) | After defining coverage gap, participants were asked whether their drug plan included such a gap, at what amount their gap began and ended, and how much they paid before, during, and after the gap | Set of medication utilization behaviors, including cost-coping behaviors (e.g., switch to cheaper med) and decreased adherence (e.g., skip pills, didn’t fill) | Interviews | -Compared with beneficiaries unaware of having a Medicare prescription drug coverage gap, those who were aware more frequently reported any behavior change, including switching to a cheaper drug | -Any behavioral change: difference of 11.3% |

| -Switching to cheaper drug: difference of 7.4% | ||||||||

| -No significant association with decreased med adherence | ||||||||

| James et al.32 | 2018 | Cross-sectional, quantitative; multivariable regression | College students at a public university in Florida (n=1450) | KFF knowledge scale and HILM | Number of visits to student health center, number of visits to a doctor’s office | Survey | -Knowledge (KFF) not significantly associated with utilization including the use of student health services | HILM score associated with overall utilization: OR 1.91 |

| -Higher insurance self-efficacy (HILM) was associated with greater probability of overall utilization but not with student health services | ||||||||

| McDonnell et al.30 | 2013 | Cross-sectional, quantitative; multivariable regression | ED visitors (or parents of pediatric patients) in Utah (n=4136) | Survey asking if respondents were aware of a law that ED must examine and treat, regardless of insurance status or ability to pay | ED visits in prior year | Survey | -Knowledge of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act associated with any ED utilization | -Any ED utilization: OR 1.44 |

| -High-frequency ED utilization: OR 1.69 | ||||||||

| -Knowledge of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act also associated with high-frequency ED utilization of at least 5 visits in last year | ||||||||

| McMenamin et al.36 | 2006 | Cross-sectional, quantitative; multivariable regression | Current smokers or recent quitters, ages 18–64 with Medicaid in the USA (n=820) | Questions regarding knowledge of coverage for several tobacco dependency treatments under their state Medicaid program | Use of tobacco dependency treatment | Survey | -Knowledge of Medicaid coverage associated with greater use of tobacco dependency treatments, including any medication and use of quitline | -Use of tobacco dependency treatments: OR 3.0 |

| -Use of quitline: OR 3.5 | ||||||||

| Morgan et al.22 | 2008 | Cross-sectional, quantitative; multivariable regression | Medicare beneficiaries in the USA (n=2997) | Subjects asked how familiar they were with Medicare and Medicare Advantage | Clinic visits, ED visits, hospital admissions in the past year | Survey | Lower familiarity with Medicare associated with: | -Clinic visits: OR 0.67 |

| -Prescription drug use: OR 0.58 | ||||||||

| -More frequent ED visits: 2.88 | ||||||||

| -Lower likelihood of clinic visits | ||||||||

| -Delayed clinic visits: OR 1.72 | ||||||||

| -Lower likelihood of prescription drug use | ||||||||

| -Delayed ED visits: OR 2.07 | ||||||||

| -Higher likelihood of more frequent ED visits | ||||||||

| -Delayed inpatient care: OR 2.60 | ||||||||

| -Non-significant association with greater inpatient care | ||||||||

| -Higher likelihood of delays due to cost for clinic visits, ED visits, and inpatient care | ||||||||

| Obrist et al.37 | 2014 | Cross-sectional, quantitative; multivariable regression | Breast cancer patients at medical center in Ghana (n=117) | Interview | Completion of medically recommended breast cancer treatment | Medical records | -Patients who completed treatment were significantly more likely to understand what their insurance covered regarding surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and other medications than those who did not complete treatment | -89.4% of patients who completed treatment understood coverage |

| -67.74% of those who did not complete treatment understood coverage | ||||||||

| -Awareness of coverage associated with completion of treatment: OR 11.859 | ||||||||

| -Those who were unaware of their insurance coverage policy for breast care had higher odds of not completing their prescribed breast cancer treatment protocol | ||||||||

| Parente et al.38 | 2005 | Cross-sectional, quantitative; multivariable regression | Medicare beneficiaries (age>65) in the USA (n=7473; with n=4296 women for mammogram analysis) | Medicare beneficiary survey with test of knowledge of Medicare coverage for flu shot and mammography | Obtaining flu shot, mammogram | Medicare claims data | -In both analytic models, individuals who had knowledge of the Medicare flu shot benefit had more flu shots in the 12-month period studied | -Model 1: 0.092 more flu shots per year |

| -Model 2: 0.182 more flu shots per year | ||||||||

| Piette and Heisler23 | 2006 | Cross-sectional, quantitative; multivariable regression | Adults age > 50 in the USA who had prescription drug coverage and at least one chronic condition (n=3119) | Survey questions assessing understanding of usual cost per prescription and knowledge about drug coverage's spending limits | Medication adherence (more specifically, cost-related) | Survey | -Low HIL regarding drug coverage caps associated with cost-related medication nonadherence | -Low HIL regarding drug coverage gaps: OR 1.7 |

| -Low HIL regarding usual out-of-pocket costs: OR 1.0 | ||||||||

| -Low HIL regarding usual out-of-pocket costs for medication not associated with cost-related medication nonadherence | ||||||||

| Reed et al.39 | 2012 | Cross-sectional, quantitative; multivariable regression | Adults (ages 18–64) with a high-deductible health plan/health savings account through Kaiser Permanente in California (n=456) | Questions assessing whether preventive office visits (e.g., annual physicals); non-preventive doctor’s office visits; preventive medical tests; and non-preventive medical tests applied toward deductible; general knowledge of deductible | Whether the amount they would have to pay caused them to delay or avoid any preventive office visits or screening tests | Survey | -Those who mistakenly thought that the deductible applied to all office visits were more likely to delay or avoid a preventive office visit because of cost than those who correctly understood the cost-sharing scheme | -23.8% of those who mistakenly thought that deductibles applied to all office visits delayed/avoided a preventative office visit, and |

| -18.1% of those who mistakenly thought that the deductible did not apply to either preventive or non-preventive visits were more likely to delay or avoid a preventive office visit, compared to | ||||||||

| -7.8% of those who knew that preventative office visits had no out-of-pocket costs delayed/avoided care | ||||||||

| -Those who mistakenly thought that the deductible did not apply to either preventive or non-preventive visits were more likely to delay or avoid a preventive office visit because of cost (18.1%) compared to those who correctly understood the cost-sharing scheme | ||||||||

| -No significant association between HIL and delay or avoidance of tests | ||||||||

| Sawyer et al.40 | 2018 | Cross-sectional, quantitative; multivariable regression | Women (ages 18–44) MTurk online survey takers in the USA (n=1083) | Knowledge questions regarding covered essential health benefits under the Affordable Care Act, and level of certainty that each response was correct | Preventive reproductive health services | Surveys | Knowledge of Affordable Care Act mandated coverage was associated with greater utilization of: | -Well-woman exams: OR 1.109 |

| -Pelvic exams: OR 1.128 | ||||||||

| -Breast exams: 1.075 | ||||||||

| -STI testing: OR 1.106 | ||||||||

| -Well-woman exams | ||||||||

| -HPV vaccination: 1.088 | ||||||||

| -Pelvic exams | ||||||||

| -Breast exams | ||||||||

| -STI testing | ||||||||

| -HPV vaccination | ||||||||

| -No significant association with receiving a Pap smear | ||||||||

| Smith et al.25 | 2018 | Cross-sectional, quantitative; multivariable regression | MTurk online survey takers in the USA (n=470) | Knowledge of health insurance terms: true/ false questions; single item regarding Affordable Care Act coverage of preventive services without out-of-pocket costs | Delaying/avoiding any care, delaying/avoiding common health care services (3 preventive and 3 non-preventive services) in the past 12 months | Survey | -Those who delayed/avoided preventive care had less general knowledge about health insurance | -General knowledge about health insurance: 67% (those who delayed care) vs. 75% (those who did not delay care) |

| -Knowledge | ||||||||

| that preventative care is covered with no out-of-pocket costs: 24% (those who delayed care) vs. 42% (those who did not delay care) | ||||||||

| -Those who delayed/avoided care were less likely to know that preventive care is covered at no out-of-pocket cost | ||||||||

| -Knowledge that preventative care is covered with no out-of-pocket costs associated with less delaying/avoiding care: OR 0.444 | ||||||||

| -General knowledge about health insurance associated with less avoidance/delay in care: OR 0.989 | ||||||||

| -Those who knew that preventive care was covered at no out-of-pocket cost were less likely to delay/avoid any care | ||||||||

| -Individuals were more likely to avoid/delay preventive care if they had lower health insurance knowledge or did not know that preventive care is covered at no out-of-pocket cost | ||||||||

| Tipirneni et al.26 | 2018 | Cross-sectional, quantitative; multivariable regression | Adults with health insurance, MTurk online survey takers in the USA (n=506) | HILM | Use of preventive and non-preventive services; delayed or forgone care owing to perceived costs (questions about specific services) | Survey | -Those with lower HILM were more likely than those with higher HILM to avoid preventive services | -23.8% of those with lower HILM avoided preventative care vs. 11.4% of those with higher HILM avoided preventative care |

| -Those with lower HILM were more likely than those with higher HILM to avoid non-preventative services | ||||||||

| -19.3% of those with lower HILM avoided non-preventative care vs. 12.6% of those with higher HILM avoided non-preventative care -Each SD increase in HILM associated with less | ||||||||

| delayed/foregone preventative care due to cost: OR 0.61 | ||||||||

| -Each SD increase in HILM associated with less delayed/foregone non-preventative care: OR 0.71 | ||||||||

| -HILM score associated with utilizing preventative services: OR 1.57 | ||||||||

| -Each 12-point increase in HILM score (~1 SD) was associated with lower likelihood of delayed or forgone care owing to cost for preventive care | ||||||||

| -Each 12-point increase in HILM score (~1 SD) was associated with lower likelihood of delayed or forgone care owing to cost for non-preventive care | ||||||||

| -HILM score was associated with a higher likelihood of preventive services use, but not with non-preventive services use | ||||||||

| Webster27 | 2011 | Cross-sectional, quantitative; multivariable regression | Adults age >65 in the USA (N=30,002) from the National Health Interview Survey | Knowledge questions related to type of Medicare coverage, whether enrolled in Medicare Advantage or HMO, whether referrals needed for specialty care, and whether paying for supplemental coverage | Number of medical office visits, ED visits, time speaking with health professional, and surgeries in past 12 months | Survey | -Low HIL associated with: | -Number of office visits (3.6 vs. 3.3) |

| ---Greater number of medical office visits | -Time since last talked with health professional: 1.3 vs. 1.2 on time scale ranging from 6 months or less to never | |||||||

| -Likelihood of talking with a health professional: 44.1% vs. 47.1% | ||||||||

| ---More time since last talked with health professional | ||||||||

| -Likelihood of surgery: 18.0% vs. 20.5% | ||||||||

| ---Lower likelihood of talking with health professional | ||||||||

| ---Lower likelihood of surgery | ||||||||

| ---No association with ED visits in the past twelve months | ||||||||

| Burns et al.31 | 2005 | Cross-sectional, quantitative; adjusted for survey weights, no covariates | Wisconsin state employees in state-sponsored health plan (2001 n=5609; 2002 n=6518) | Yes no question on whether insurance covers list of specific tobacco cessation therapies | Use of tobacco cessation medications | Survey | -HIL related to coverage of tobacco cessation therapies associated with utilization of tobacco cessation therapies | -39.6% utilization among those aware vs. 3.5% among those unaware of benefit |

| Lischko and Burgess29 | 2010 | Cross-sectional, quantitative; multivariable regression | Massachusetts state employees (age <65) continuously enrolled in health plan for 3 years (n=1322) | Knowledge questions regarding co-pays for different services | ED or office visits | Claims data, Survey | -Greater knowledge of costs was associated with utilization of office visits | -0.0923 more office visits for those with the highest level of cost-sharing knowledge vs. no knowledge |

| -Those who overestimated or accurately knew co-pays were more likely to delay/avoid care than those who underestimated co-pays | ||||||||

| -Those who overestimated (OR 2.47) or accurately knew co-pays (OR 1.87) were more likely to delay/avoid office visits | ||||||||

| -Knowledge of specific co-pays had no association with office visits or ED utilization | ||||||||

| Edward et al.21 | 2018 | Cross-sectional, mixed methods; unadjusted | Latinx (primarily Spanish speaking) adults attending health insurance enrollment event (n=139) | Subjects asked to define health insurance terms (copay, premium, deductible) | Whether participants had accessed health care in the USA | Surveys, semi-structured interviews | No association between HIL and time since last accessed health care | -N/A |

| Nobles et al.28 | 2019 | Cross-sectional, mixed methods; unadjusted | Undergraduate and graduate students at a single university in Virginia (n=455) | Knowledge of health insurance vocabulary and ability to apply knowledge to determine cost-sharing, self-rated understanding of insurance terminology | Delayed/forgone medical care because of confusion about health insurance plan | Survey | -Low HIL associated with delayed or forgone care | -24.4% indicated that lack of understanding of their health insurance stopped or delayed them from seeking medical care in the past |

Abbreviations: HIL, health insurance literacy; OR, odds ratio; TANF, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families; HILM, Health Insurance Literacy Measure, a subjective measure of confidence in health insurance decision-making; KFF, Kaiser Family Foundation objective measure of health insurance knowledge; MTurk, Amazon Mechanical Turk; STI, sexually transmitted infection; HMO, health maintenance organization; ED, Emergency Department

Included studies are sorted by study type and presented in the same order as in Table 1

Overall, HIL was significantly associated with various types of health care utilization, with 19 of the 21 included studies showing statistically significant findings (Table 1). As Table 2 highlights, there was significant variability across studies in terms of the effect size of these relationships. Significant differences when comparing high HIL individuals to lower HIL individuals ranged from 1.5 to 36.1% absolute differences in health care utilization or medication use, 0.42 to 0.99 odds of delaying or foregoing medical care, and 1.08 to 11.86 greater odds of utilizing health services. A wide variety of utilization outcomes were measured in these studies, ranging from specific services (e.g., pneumococcal vaccination,20 mammography18) to broad measures (e.g., time since last utilization of health care21).

HIL and Preventative/Primary Care

In general, higher levels of HIL were associated with greater utilization of outpatient and preventive care services. Of the 13 studies assessing the association between HIL and utilization of primary care or other preventive services, 10 showed a positive association between higher HIL and greater use of preventive services and 3 showed no significant difference.

HIL and Avoidance of Needed Care

Of the 9 studies assessing the association between HIL and delaying or avoiding care, 8 showed that low HIL was associated with delaying or avoiding care.21–28 For example, in a study of adults with high-deductible health plans in the Kaiser Permanente System, 24% of those who mistakenly thought that their deductible applied to all office visits (when, in fact, preventive care visits had no out-of-pocket costs) said they delayed or avoided a preventive office visit because of cost, while only eight percent of those who correctly understood the cost-sharing scheme did so (OR=3.00).39 Two of these studies also demonstrated a significant association between low HIL and lower rates of medication adherence.22,23

HIL and Acute Care Utilization

Studies assessing the association between HIL and emergency department utilization (n=5) had mixed findings, with three studies showing no significant association,26,27,29 one showing higher utilization,30 and one showing lower utilization.22 Of note, these five studies used five different assessments of HIL. One study, McDonnell et al., also assessed knowledge of broader health insurance policies by measuring participants’ awareness of the federal Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA), which requires emergency departments to care for patients regardless of insurance status or ability to pay; in this study, greater knowledge about the EMTALA policy was associated with higher levels of emergency department use.30 Two of three studies assessing utilization of inpatient or surgical care showed that HIL was associated with greater utilization,22,27 and one showed no statistical significance.26

Measures of HIL Used Across Studies

HIL was measured in a variety of ways in the included studies. We identified 21 different ways of measuring HIL across the 21 studies, 19 of which were novel measures created specifically for the study. To date, there is only one validated tool that measures HIL—the Health Insurance Literacy Measure—which assesses subjective confidence and behaviors associated with selecting and utilizing health insurance.13 Published in 2014, the Health Insurance Literacy Measure was used as a measurement tool in only two of the included studies. Most other studies used measures that were created by the authors for the specific purpose of the study. For example, Kneipp et al.19 created a 20-item questionnaire about whether Medicaid covers specific services. Some studies assessed HIL very granularly; for example, Burns, Rosenberg, and Fiore were interested in how tobacco users utilized certain tobacco cessation therapies and assessed subjects’ awareness of insurance coverage for those specific therapies.31

James et al. 32 used two assessments of HIL, an objective measure developed by the Kaiser Family Foundation that assessed fact-based knowledge about insurance coverage (e.g., the definition of a deductible)2 and the Health Insurance Literacy Measure, a more subjective measure described above. The authors found that insurance knowledge (as measured by the Kaiser Family Foundation scale) was not associated with utilization patterns; however, insurance self-efficacy (as measured by the Health Insurance Literacy Measure) was positively associated with utilization. The only other study that utilized the Health Insurance Literacy Measure, Tipirneni et al., found that lower HIL was associated with greater likelihood of delayed or forgone care owing to cost and a lower likelihood of utilizing preventive, but not non-preventive, services.26

Discussion

Our systematic review found that in most studies lower HIL was associated with lower health care utilization or greater avoidance of a wide variety of health care services. However, there is a dearth of literature in this area. Several studies demonstrated that low HIL was associated with underutilization of certain high-value services, including primary care visits, other preventive care visits, and adherence to prescription medication regimens for chronic conditions. Not surprisingly, greater specificity of the HIL measurement often had stronger associations with health care utilization patterns, though this was not consistent across studies. This highlights the need for HIL researchers to determine whether it is more useful to assess HIL in a context-specific way (e.g., knowledge of coverage of a specific service) or as a general skill or behavior that will be more likely to generalize across multiple health care contexts.

Another theme of our systematic review was that HIL may enable cost-conscious navigation of the health care system, and low HIL could be a barrier to effective care navigation. For example, eight of the nine studies that assessed delayed or forgone care found that lower HIL was associated with avoidance of needed care. This suggests that HIL is a key mediator of effective navigation of the many layers of the US health care system.

Our analysis of studies assessing HIL and health care utilization dovetails with other literature assessing the relationship between HIL and navigation of health insurance plan selection and affordability. Studies of factors influencing how people select insurance plans have shown that a lack of cost transparency33 and a perceived lack of reliable information about how to distinguish different insurance plans34 are significant barriers towards selecting a plan. One study found that individuals over the age of 50 with concerns about the affordability of health insurance were more likely to delay or avoid care.35 Thus, improving HIL may enable individuals to exhibit cost-conscious care navigation on two fronts: choosing an appropriately tailored insurance plan and accessing and utilizing the health care system after obtaining insurance. Ideally, this would be facilitated by laws regulating how insurance plans communicate to consumers about the details of their benefits and cost-sharing. The ACA included provisions to improve the transparency of health plans’ cost-sharing, but the implementation of these provisions has been thus far delayed.42

Our findings also beg the question: to improve the use of high-value care, should health care professionals aim to raise the level of HIL among all patients or focus on communicating health insurance terms and concepts in plain language? The intervention studies included in this review focused on the unique details of specific health insurance plans and specific covered services (e.g., education on Medicare’s coverage of the influenza vaccine), which may not translate to broader use of high-value care (e.g., use of primary care vs. the emergency department). In addition, changes in the availability and type of insurance, medication formularies, in-network providers, and out-of-pocket costs of various services may make the implementation of any HIL intervention to encourage specific types of high-value care challenging and short-lived. Further studies could delineate whether HIL performs similarly across all populations and insurance models, or if specific populations may benefit from targeted interventions aimed at increasing specific aspects of HIL.42

As noted earlier, despite the importance of the topic, our review found that research about HIL is limited, both by the number of studies conducted to date and by the number of validated tools available to assess HIL. The substantial majority of studies in the systematic review relied upon a HIL assessment tool that was created by the authors specifically for that study, making comparisons across HIL studies challenging. Several of the reported measures were narrow both in their assessment of HIL (e.g., knowledge of out-of-pocket costs for a specific therapy) and in their examination of health care utilization (e.g., utilization of that specific therapy). A recent study that was published after the date of our search compared two other HIL scales (likelihood of utilization vs. confidence in utilization) and found divergent results in individuals’ delaying care or reporting burdensome medical bills.41 This study highlights the difficulty of developing an assessment tool that captures both the broad concept of HIL and the specific applicability to health insurance plan selection and health care navigation. Even the validated Health Insurance Literacy Measure tool focuses on measuring confidence in HIL (a subjective measure) but lacks a knowledge-based/objective assessment. Development and validation of new comprehensive measures of HIL are needed to advance this emerging and valuable field. Despite these differences in measurement, 19 of the 21 studies reported a statistically significant outcome, although there may be a publication bias that has led other studies with negative or null results to remain unpublished.

Our systematic review was conducted with a pre-specified protocol, comprehensive review of the literature, and coding my multiple reviewers. However, our review was primarily focused on biomedical and health care databases; we did not conduct a search with other types of databases such as those used in legal literature.

CONCLUSION

In summary, the literature addressing the association between HIL and health care utilization is limited and lacks standardized measures to assess HIL. This review of the current literature suggests that low HIL is a barrier to effective utilization of important health care services such as primary care, preventive services, medication adherence, and minimizing delays or avoidance of care for urgent needs. Thus, improving HIL and increasing plain language communication of health insurance plan features at the point of care navigation may be effective strategies to encourage more effective and cost-conscious utilization.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 24 kb)

Author Contribution

All those who contributed to this manuscript are listed as authors.

Funding

The study was supported by the Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan. Dr. Tipirneni is additionally supported by a K08 Clinical Scientist Development Award from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Scherer is additionally supported by a K01 Mentored Research Scientist Award from the National Institute on Aging and a U01 Cooperative Agreement with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Loewenstein G, Friedman JY, McGill B, et al. Consumers’ misunderstanding of health insurance. J Health Econ. 2013;32(5):850–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norton M, Hamel L, Brodie M. Assessing Americans’ familiarity with health insurance terms and concepts. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2014. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/poll-finding/assessing-americans-familiarity-with-health-insurance-terms-and-concepts. Accessed August 24, 2020.

- 3.Feinberg I, Greenberg D, Tighe EL, Ogrodnick MM. Health Insurance Literacy and Low Wage Earners: Why Reading Matters. Adult Literacy Education. 2019;1(2):4–18. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams CB, Pensa MA, Olson DP. Health insurance literacy in community health center staff. J Public Health 2020:1-5.

- 5.McCormack L, Bann C, Uhrig J, Berkman N, Rudd R. Health insurance literacy of older adults. J Consum Aff. 2009;43(2):223–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6606.2009.01138.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ubel PA, Comerford DA, Johnson E.Healthcare.gov 3.0—Behavioral economics and insurance exchanges. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:695-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Politi MC, Kaphingst KA, Liu JE, et al. A randomized trial examining three strategies for supporting health insurance decisions among the uninsured. Med Decis Mak. 2016;36(7):911–22. doi: 10.1177/0272989X15578635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Politi MC, Kuzemchak MD, Liu J, et al. Show Me My Health Plans: Using a Decision Aid to Improve Decisions in the Federal Health Insurance Marketplace. MDM Policy Pract. 2016;1(1):2381468316679998. doi: 10.1177/2381468316679998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(2):97–107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walters R, Leslie SJ, Polson R, Cusack T, Gorely T. Establishing the efficacy of interventions to improve health literacy and health behaviours: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1040. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08991-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.PRISMA checklist. http://prisma-statement.org/. Accessed August 6, 2020.

- 12.Luster J, Smith J, Yagi B, Farron M, Scherer A, Tipirneni R. Health insurance literacy and health care utilization: a systematic review. PROSPERO 2020 CRD42020147793 Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020147793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Paez KA, Mallery CJ, Noel H, et al. Development of the Health Insurance Literacy Measure (HILM): conceptualizing and measuring consumer ability to choose and use private health insurance. J Health Commun. 2014;19 Suppl 2(sup2):225-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Carrasquillo O. Health Care Utilization. In: Gellman MD, Turner JR, editors. Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine. New York: Springer New York; 2013. pp. 909–10. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Distiller-Systematic Review. Evidence Partners. https://www.evidencepartners.com/products/distillersr-systematic-review-software/. Accessed August 24, 2020.

- 16.Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean RS. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS) BMJ Open. 2016;6(12):e011458. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alesci NL, Boyle RG, Davidson G, Solberg LI, Magnan S. Does a health plan effort to increase smokers' awareness of cessation medication coverage increase utilization and cessation? Am J Health Promot. 2004;18(5):366–9. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-18.5.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fox SA, Stein JA, Sockloskie RJ, Ory MG. Targeted mailed materials and the Medicare beneficiary: increasing mammogram screening among the elderly. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(1):55–61. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kneipp SM, Kairalla JA, Lutz BJ, et al. Public health nursing case management for women receiving temporary assistance for needy families: a randomized controlled trial using community-based participatory research. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(9):1759–68. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ehresmann KR, Ramesh A, Como-Sabetti K, Peterson DC, Whitney CG, Moore KA. Factors associated with self-reported pneumococcal immunization among adults 65 years of age or older in the Minneapolis-St. Paul metropolitan area. Prev Med. 2001;32(5):409–15. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edward J, Morris S, Mataoui F, Granberry P, Williams MV, Torres I. The impact of health and health insurance literacy on access to care for Hispanic/Latino communities. Public Health Nurs. 2018;35(3):176–83. doi: 10.1111/phn.12385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morgan RO, Teal CR, Hasche JC, et al. Does poorer familiarity with Medicare translate into worse access to health care? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(11):2053–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piette JD, Heisler M. The relationship between older adults' knowledge of their drug coverage and medication cost problems. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(1):91–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsu J, Fung V, Price M, et al. Medicare beneficiaries' knowledge of Part D prescription drug program benefits and responses to drug costs. JAMA. 2008;299(16):1929–36. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.16.1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith KT, Monti D, Mir N, Peters E, Tipirneni R, Politi MC. Access is necessary but not sufficient: factors influencing delay and avoidance of health care services. MDM Policy Pract. 2018;3(1):2381468318760298. doi: 10.1177/2381468318760298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tipirneni R, Politi MC, Kullgren JT, Kieffer EC, Goold SD, Scherer AM. Association between health insurance literacy and avoidance of health care services owing to cost. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(7):e184796. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.4796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Webster NJ. Medicare Knowledge and Health Service Utilization Among Older Adults. In: Jacobs Kronenfeld J, ed. Access To Care and Factors That Impact Access, Patients as Partners In Care and Changing Roles of Health Providers. Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2011:273-97.

- 28.Nobles AL, Curtis BA, Ngo DA, Vardell E, Holstege CP. Health insurance literacy: a mixed methods study of college students. J Am Coll Heal. 2019;67(5):469–78. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2018.1486844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lischko AM, Burgess JF., Jr Knowledge of cost sharing and decisions to seek care. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(4):298–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McDonnell WM, Gee CA, Mecham N, Dahl-Olsen J, Guenther E. Does the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act affect emergency department use? J Emerg Med. 2013;44(1):209–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burns ME, Rosenberg MA, Fiore MC. Use of a new comprehensive insurance benefit for smoking-cessation treatment. Prev Chronic Dis. 2005;2(4). https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2005/oct/05_0007.htm [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.James TG, Sullivan MK, Dumeny L, Lindsey K, Cheong J, Nicolette G. Health insurance literacy and health service utilization among college students. J Am Coll Heal. 2020;68(2):200–6. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2018.1538151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.George N, Grant R, James A, Mir N, Politi MC. Burden associated with selecting and using health insurance to manage care costs: results of a qualitative study of nonelderly cancer survivors. Med Care Res Rev. 2018;1077558718820232. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Furtado KS, Kaphingst KA, Perkins H, Politi MC. Health insurance information-seeking behaviors among the uninsured. J Health Commun. 2016;21(2):148–58. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2015.1039678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tipirneni R, Solway E, Malani P, et al. Health insurance affordability concerns and health care avoidance among US adults approaching retirement. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1920647. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McMenamin SB, Halpin HA, Bellows NM. Knowledge of Medicaid coverage and effectiveness of smoking treatments. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(5):369–74. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Obrist M, Osei-Bonsu E, Ahwah B, et al. Factors related to incomplete treatment of breast cancer in Kumasi. Ghana Breast. 2014;23(6):821–8. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parente ST, Salkever DS, DaVanzo J. The role of consumer knowledge of insurance benefits in the demand for preventive health care among the elderly. Health Econ. 2005;14(1):25–38. doi: 10.1002/hec.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reed ME, Graetz I, Fung V, Newhouse JP, Hsu J. In consumer-directed health plans, a majority of patients were unaware of free or low-cost preventive care. Health Aff. 2012;31(12):2641–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sawyer AN, Kwitowski MA, Benotsch EG. Are you covered? associations between patient protection and affordable care act knowledge and preventive reproductive service use. Am J Health Promot. 2018;32(4):906–15. doi: 10.1177/0890117117736091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Call KT, Conmy A, Alarcón G, Hagge SL, Simon AB. Health insurance literacy: How best to measure and does it matter to health care access and affordability? Res Social Adm Pharm. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jenny HE, Jenny BE. A Healthy Dose of Price Transparency in US Health Care Services. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(7):544–545. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.0754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 24 kb)