Summary

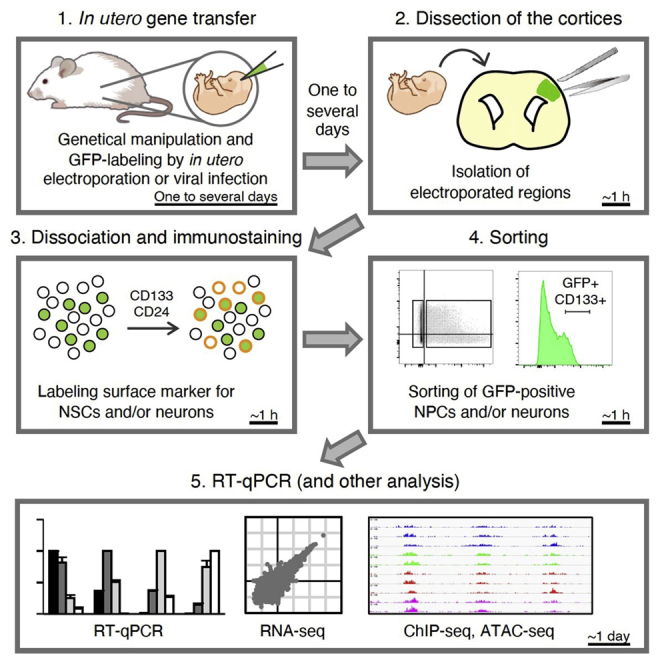

The embryonic mammalian neocortex includes neural progenitors and neurons at various stages of differentiation. The regulatory mechanisms underlying multiple aspects of neocortical development—including cell division, neuronal fate commitment, neuronal migration, and neuronal differentiation—have been explored using in utero electroporation and virus infection. Here, we describe a protocol for investigation of the effects of genetic manipulation on neural development through direct isolation of neural progenitors and neurons from the mouse embryonic neocortex by fluorescence-activated cell sorting.

For complete details on the use and execution of this protocol, please refer to Tsuboi et al. (2018) and Sakai et al. (2019).

Subject areas: Cell Biology, Cell isolation, Flow Cytometry/Mass Cytometry, Developmental biology, Molecular Biology, Gene Expression, Neuroscience, Stem Cells, Cell Differentiation

Graphical abstract

Highlights

Direct isolation of neural progenitors and neurons from the mouse embryonic neocortex

Purification of neural cells at various stages of differentiation using wild-type mice

Protocol enables biochemical analyses of neural cells genetically manipulated in vivo

Applicable for transcriptomic and epigenomic analyses

The embryonic mammalian neocortex includes neural progenitors and neurons at various stages of differentiation. The regulatory mechanisms underlying multiple aspects of neocortical development—including cell division, neuronal fate commitment, neuronal migration, and neuronal differentiation—have been explored using in utero electroporation and virus infection. Here, we describe a protocol for investigation of the effects of genetic manipulation on neural development through direct isolation of neural progenitors and neurons from the mouse embryonic neocortex by fluorescence-activated cell sorting.

Before you begin

In utero gene transfer

Timing: One to several days

The protocol is typically applied to mouse embryos that have been genetically manipulated by in utero electroporation or virus infection with a plasmid or viral vector encoding a protein or short hairpin RNA (shRNA) of interest as well as a fluorescent protein such as green fluorescent protein (GFP) (Gaiano et al., 1999; Kuwayama et al., 2020; Matsui et al., 2011; Tabata and Nakajima, 2001). It can also be applied to wild-type embryos as well as to transgenic embryos such as those that specifically express a Venus fluorescent protein in neural progenitors under the control of the rat Nestin enhancer (Nestin-d4Venus embryos) (Sunabori et al., 2008). For wild-type embryos, cell isolation is performed with antibodies to surface antigens of neural progenitors or of differentiated neurons, such as CD133 (a.k.a. prominin) and CD24, respectively (Pruszak et al., 2009; Uchida et al., 2000).

Note: We here describe the method to isolate neural cells from the mouse telencephalon at embryonic day (E) 8 or E9 or from the neocortex at E10 to 20 days postcoitus (dpc).

Note: For this protocol, we mainly use the ICR mouse strain, stage progression for which is slightly earlier compared with that for the C57BL/6 strain. For example, E12 of ICR roughly corresponds to E13 of C57BL/6.

Note: As described in the Limitations section, it is difficult to isolate neurons after they have elaborated neurites, given that enzymatic digestion of the elaborated neurites may impair the viability of or kill the cells.

Setup of FACS machine

Timing: ~1 h

-

1.

Set up the FACSAria instrument before dissection of embryos.

-

a.

Turn on the FACSAria, desktop computer, and lasers.

-

b.

Perform prime after tank refill and fluidics startup.

-

c.

Remove closed-loop nozzle and set the 100-μm nozzle.

-

d.

Turn on the stream and perform cytometer setup and tracking (CST) quality control.

-

e.

Set Accudrop delay and check the sorting line by Test Sort.

Note: Nozzle size should be ≥100 μm. The 85-μm nozzle may inflict more damage on neural cells.

Note: The neutral density (ND) filter should be >1.5.

Preparation of dissociation solutions

Timing: 30 min

-

2.

Thaw Neuron Dissociation Solutions (refer to Key Resources Table) in the indicated volume at step 5.

Note: We use thawed solutions that have been stored at 4°C for up to 1 month. For longer storage, we divide the solutions into smaller batches and refreeze them at −80°C.

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-CD133-PE (1:400) | BioLegend | Cat# 141204; RRID: AB_10722606 |

| Anti-CD24-PE (1:400) | BioLegend | Cat# 138504; RRID: AB_10578416 |

| Anti-CD133-APC (1:400) | BioLegend | Cat# 141208; RRID: AB_10896756 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| DMEM/F12 | Sigma | Cat# D8062 |

| Penicillin-streptomycin | Gibco | Cat# 15140-122 |

| Percoll | Sigma | Cat# P1644- |

| BSA | FUJIFILM Wako Chemicals | Cat# 013-15143 |

| NaCl | FUJIFILM Wako Chemicals | Cat# 191-01665 |

| KCl | FUJIFILM Wako Chemicals | Cat# 163-03545 |

| Na2HPO4-12H2O | FUJIFILM Wako Chemicals | Cat# 196-02835 |

| KH2PO4 | FUJIFILM Wako Chemicals | Cat# 169-04245 |

| NaOH | FUJIFILM Wako Chemicals | Cat# 194-18865 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| RNAiso plus | Takara | Cat# 9109 |

| ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Master Mix with gDNA Remover | Toyobo | Cat# FSQ-301 |

| THUNDERBIRD SYBR qPCR Mix | Toyobo | Cat# QPS-201T |

| Neuron Dissociation Solutions | FUJIFILM Wako Chemicals | Cat# 291-78001 |

| Experimental models: organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: Jcl:ICR | CLEA Japan, Inc. | N/A |

| Mouse: Jcl:ICR | Japan SLC, Inc. | N/A |

| Mouse: Nestin-d4Venus | RIKEN BRC | RBRC04058 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| RT-qPCR primers, see Table 1 | Eurofins Genomics | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| FACS DIVA | BD | https://www.bdbiosciences.com/ja-jp/instruments/research-instruments/research-software/flow-cytometry-acquisition/facsdiva-software |

| FlowJo | BD | https://www.flowjo.com/solutions/flowjo |

| LightCycler 480 Software, version 1.5.1 | Roche | https://lifescience.roche.com/global_en/products/lightcycler14301-480-software-version-15.html |

| Other | ||

| 5 mL Round Bottom Polystyrene Test Tube with Cell Strainer Snap Cap | Falcon | Cat# 352235 |

| FACSAria | BD | https://www.bdbiosciences.com/en-us/instruments/research-instruments/research-cell-sorters/facsaria-iii |

| LightCycler 480 | Roche | https://diagnostics.roche.com/global/en/products/systems/lightcycler-480-system.html#productInfo |

| NanoDrop | Thermo Fisher | https://www.thermofisher.com/jp/en/home/industrial/spectroscopy-elemental-isotope-analysis/molecular-spectroscopy/ultraviolet-visible-visible-spectrophotometry-uv-vis-vis/uv-vis-vis-instruments/nanodrop-microvolume-spectrophotometers/nanodrop-products-guide.html |

Table 1.

Primer sequences for RT-qPCR

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| Gapdh | ATGAATACGGCTACAGCAACAGG | CTCTTGCTCAGTGTCCTTGCTG |

| Nestin | TGAAGCACTGGGAAGAGTAG | TAACTCATCTGCCTCACTGTC |

| Sox2 | CATGAGAGCAAGTACTGGCAAG | CCAACGATATCAACCTGCATGG |

| Pax6 | CGGAGGGAGTAAGCCAAGAG | TCTGTCTCGGATTTCCCAAG |

| Eomes | CATGGACATCCAGAATGAGC | CAGGAGGAACTAATCTCTTCTTTAAC |

| Neurod1 | TACGACATGAACGGCTGCTA | TCTCCACCTTGCTCACTTT |

| Tubb3 | ACACAGACGAGACCTACT | GCAGACACAAGGTGGTT |

| Satb2 | GTCTCCTCTGCCTCTAGC | GCGCCGTCCACCTTAATA |

| Tbr1 | CCAAGGACCTGTCCGACTC | GCTCGTAAATCCCCGAGTC |

Materials and equipment

FACS

This protocol is based on the use of a FACSAria instrument (BD) for isolation of neural cells. Potential alternative machines are MoFlo (Beckman Coulter) and Cell Sorter SH800S (Sony), which we have confirmed to be suitable for sorting of neural cells.

qPCR system

This protocol describes the quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) procedure as performed in a 5-μl reaction volume with a LightCycler 480 system (Roche) and THUNDERBIRD SYBR qPCR Mix. Other qPCR machines, such as LC96 (Roche), and other reagents based on SYBR, such as a KAPA SYBR Fast qPCR Kit (KAPA Biosystems), LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master (Roche), and a QuantiNova SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen), can also be used.

10× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

| Reagent | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| NaCl | 1.37 M | 320 g |

| KCl | 26.8 mM | 8 g |

| Na2HPO4-12H2O | 101 mM | 145.2 g |

| KH2PO4 | 17.6 mM | 9.6 g |

| ddH2O | Up to 4 l | |

| Total | 4 l |

Store at 18°C–24°C, and do not store more than 1 year.

Note: Adjust the pH of the solution with NaOH to 7.3.

0.2% BSA/PBS

| Reagent | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Bovine serum albumin (BSA) | 0.2% (w/v) | 0.1 g |

| 10× PBS | 1× | 5 mL |

| ddH2O | Up to 50 mL | |

| Total | 50 mL |

Store at 4°C, and do not store more than 1 month.

DMEM/F12 containing 1% PS

| Reagent | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Penicillin-streptomycin (PS) | 1% (v/v) | 5 mL |

| DMEM/F12 | Up to 500 mL | |

| Total | 500 mL |

Store at 4°C, and do not store more than 1 month.

Alternatives: This protocol uses Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM)–nutrient mixture F12 containing 1% PS for dissection of the embryonic brain. Other appropriate solutions such as PBS and artificial cerebrospinal fluid can also be used.

Step-by-step method details

Dissociation of embryonic mouse neocortex

Timing: 1–2 h

-

1.

Add DMEM/F12 containing 1% PS to a glass dish cooled with ice or an ice pack.

-

2.

Dissect the neocortex from embryos placed in the glass dish and isolate the region of interest with the use of a stereomicroscope.

Note: As a negative control, we isolate the neocortex of nonmanipulated embryos or nonmanipulated brain regions, such as the ventral area.

Note: When dissecting a neocortex subjected to electroporation with a fluorescent protein expression plasmid, it is possible to isolate only the electroporated region visible under a fluorescence stereomicroscope for efficient and fast cell sorting. However, for comparison of electroporated cells between neocortices transfected with test or control plasmids, the same neocortical region should be dissected to ensure the same CD133 distribution of the fluorescent protein–negative cell population. This is important for use of the fluorescent protein–negative population as an appropriate internal control (Figure 1C).

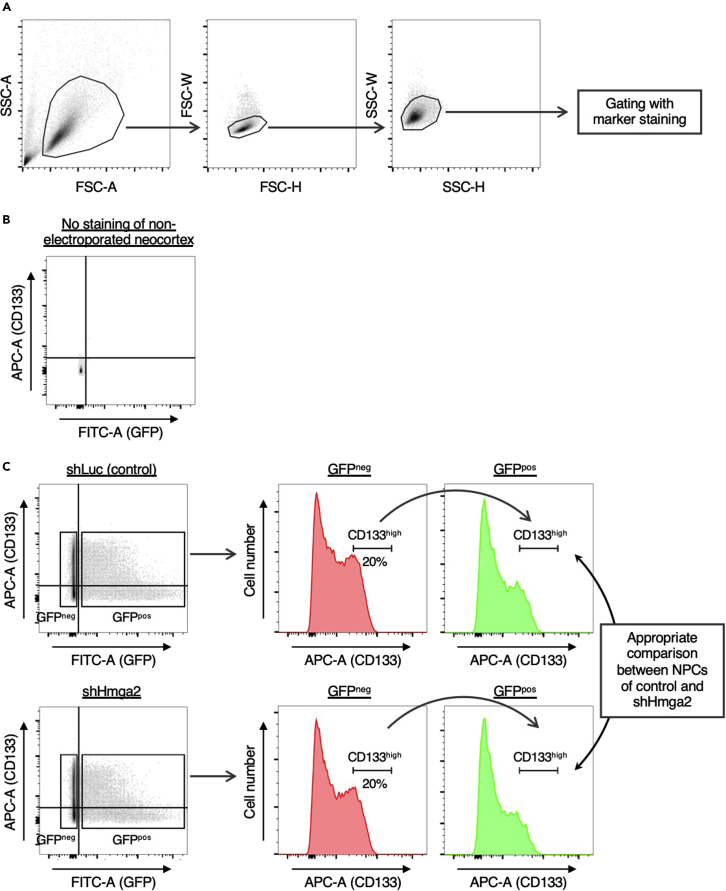

Figure 1.

Gating strategies for isolation of CD133high neural progenitors from the embryonic neocortex after in utero electroporation with a plasmid encoding GFP

Plasmids encoding GFP and either control (shLuc) or Hmga2 (shHmga2) shRNAs were introduced into neural progenitors of mouse embryos at E11 by in utero electroporation as described previously (Sakai et al., 2019). Neocortical cells were dissociated at E13, stained with APC-conjugated antibodies to CD133, and subjected to FACS.

(A) Debris and doublets were removed as described in steps 24a and 24b.

(B and C) GFP and CD133 profiles of negative control (B) and electroporated and stained (C) samples. For electroporated samples, the CD133high population (top 20% of CD133-expressing cells) was defined with the use of the GFPneg fraction, and the gating was then applied to the GFPpos fraction, as described in steps 24c to 24e. This approach allows appropriate comparison between neural progenitors of control and shHmga2 samples.

Note: For the dissection of cortical tissues from mouse embryos, Viesselmann et al. (2011) provided useful a visual protocol (Viesselmann et al., 2011).

-

3.

Transfer the neocortex into a 1.5-mL tube.

-

4.

Leave the tube briefly to let the neocortex sedimented and discard the medium.

-

5.

Add an appropriate volume of Enzyme Solution of Neuron Dissociation Solutions.

Note: The volumes of Neuron Dissociation Solutions are adjusted according to the stage and number of neocortices, as indicated in the following examples.

| Stage (ICR) | Number of neocortices | Volume of solutions (μl) |

|---|---|---|

| E8– E14 | 1 telencephalon or neocortex | 50 |

| E15–20 dpc | 1 neocortex | 100 |

| E8–E12 | 20–30 neocortices (1 pregnant mouse) | 100 |

| E13–E16 | 20–30 neocortices (1 pregnant mouse) | 200 |

| E17–20 dpc | 20–30 neocortices (1 pregnant mouse) | 300 |

-

6.

Incubate for 20 min in a heat block at 37°C.

-

7.

Mix with a pipette (~20 times) attached to a P200 or P1000 Pipetman (Gilson).

-

8.

Centrifuge at 600 × g for 2 min at room temperature (18°C–24°C).

Note: For steps 8 and 10, centrifugation should be performed at room temperature (not 4°C), given that Neuron Dissociation Solutions may include DNase that is inactivated at 4°C.

-

9.

Discard the supernatant, add Dispersion Solution to the pellet, resuspend the pellet with the use of a pipette, and add Isolation Solution below the Dispersion Solution.

-

10.

Centrifuge at 600 × g for 2 min at room temperature.

-

11.

Discard the supernatant, add 200 μl of 0.2% BSA/PBS to the pellet, and resuspend with a pipette.

Note: We remove debris with the use of Percoll solution at steps 12 to 15 for neocortices at E15 to 20 dpc, given that such debris can cause clogging of the FACS machine. We skip steps 12 to 15 for neocortices at earlier stages.

-

12.

Prepare the following Percoll solution in another 1.5-mL tube.

Percoll solution

| Reagent | Final Concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Percoll | 22.5% (v/v) | 45 μl |

| 10× PBS | 5 μl | |

| 0.2% BSA/PBS | Up to 150 μl | |

| Total | 200 μl |

-

13.

Layer cell suspension on top of Percoll solution.

-

14.

Centrifuge at 600 × g for 2 min at 4°C.

-

15.

Discard the supernatant, add 200 μl of 0.2% BSA/PBS to the pellet, and resuspend with a pipette.

Immunostaining

Timing: 20–30 min

-

16.

Add fluorescent label–conjugated antibodies, such as phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated anti-CD133, allophycocyanin (APC)–conjugated anti-CD133, and PE-conjugated anti-CD24 at a 1:400 dilution.

Note: Prepare negative control samples for immunostaining.

Note: For immunostaining of surface antigen on neural cells, Menon et al. (2014) provided a useful visual protocol (Menon et al., 2014).

-

17.

Incubate for 10 min at 4°C.

Note: When staining with antibodies other than CD24 or CD133, it may be better to extend this time.

-

18.

Centrifuge at 600 × g for 2 min at 4°C.

-

19.

Discard the supernatant and add 300 μl of 0.2% BSA/PBS to the pellet for washing.

-

20.

Centrifuge at 600 × g for 2 min at 4°C.

-

21.

Discard the supernatant, add an appropriate volume of 0.2% BSA/PBS to the pellet, and resuspend with a pipette.

-

22.

Filter and transfer the suspension using 5 mL Round Bottom Polystyrene Test Tube with Cell Strainer Snap Cap.

Note: We usually prepare the cell suspension at a density of ~ 1 × 107 cells/mL or in a volume of >200 μl. Higher cell densities increase the speed of cell collection but result in a greater loss of marker-positive cells.

Cell sorting

Timing: 20–60 min

-

23.

Run control samples, including non-stained and single-stained samples, in order to check for potential spectral overlap. If necessary, set up compensation.

-

24.Run fully stained samples and set gates. The following is an example for neocortical cells expressing GFP and stained with APC-conjugated anti-CD133 (Figure 1).

-

a.Remove debris according to the plot of forward scatter (FSC)–A and side scatter (SSC)–A.

-

b.Remove doublets according to plots of FSC-W and FSC-H and of SSC-W and SSC-H.

-

c.Separate GFP-positive (GFPpos) and GFP-negative (GFPneg) populations on the basis of FITC-A signals.

-

d.Determine cell populations—such as CD133high cells using APC-A signals—with the use of GFPneg cells.

-

e.Apply gates determined with the GFPneg population to the GFPpos population.

-

a.

Note: For cells transgenic for Nestin-d4Venus or wild-type cells stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD133, high, medium, low, and negative fractions are determined as in Figures 2A and 2B.

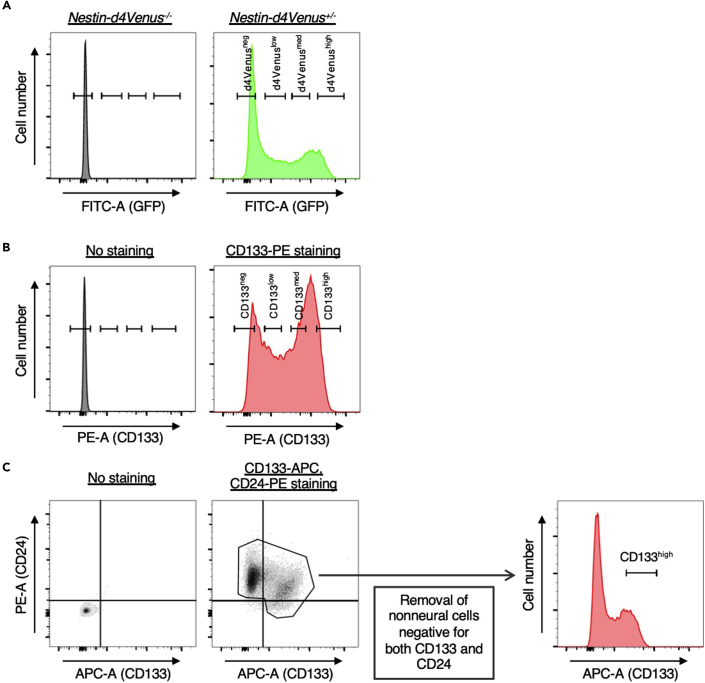

Figure 2.

Gating strategies for isolation of neural progenitors and neurons from the neocortex of Nestin-d4Venus or wild-type embryos

(A) Neocortical cells of Nestin-d4Venus–/– or Nestin-d4Venus+/– embryos at E14 were dissociated and subjected to FACS analysis as described previously (Sakai et al., 2019). The gates for dVenus-high, -medium, -low, and -negative cells are shown.

(B) Neocortical cells of wild-type embryos at E14 were dissociated, stained (or not) with PE-conjugated antibodies to CD133, and subjected to FACS analysis as described previously (Sakai et al., 2019). The gates for CD133-high, -medium, -low, and -negative cells are shown.

(C) Neocortical cells of C57BL/6 embryos at E15 were dissociated, stained (or not) with both APC-conjugated antibodies to CD133 and PE-conjugated antibodies to CD24, and subjected to FACS analysis. Nonneural cells determined as those negative for both CD133 and CD24 were removed. The gate for CD133-high cells is shown.

-

25.Prepare 1.5-mL collection tubes.

-

a.Coat the inner wall of 1.5-mL tubes with 500 μl of 1% BSA/PBS.

-

b.Add 500 μl of 0.2% BSA/PBS to the coated 1.5-mL tubes as a cushion.

-

a.

-

26.

Sort the populations of interest into the prepared 1.5-mL tubes.

Note: Given that the volume of one drop is ~4 nano liter for FACSAriaII and III with 100 μm nozzle, we can collect 250,000 cells into one 1.5-mL tube.

-

27.

Invert and mix each tube immediately after sorting. Given that the sheath solution—in this case, FACS Flow (BD)—may contain a detergent, its dilution by mixing with the cushion solution helps to preserve cell viability.

-

28.

Centrifuge at 600 × g for 5 min at 4°C.

-

29.

Discard the supernatant.

-

30.For reverse transcription (RT) and qPCR and RNA-seq analyses, freeze the cell pellet with liquid N2 and store at −80°C. 10,000 cells are enough for RT-qPCR and usual RNA-seq analyses, and 1,000 cells are used for Quartz-seq analysis (Eto et al., 2020; Kuwayama et al., 2020; Sakai et al., 2019).

Pause point: Store the cell pellets at −80°C for more than 1 year.Note: For other types of biochemical analysis, proceed to the appropriate treatment as follows.

Pause point: Store the cell pellets at −80°C for more than 1 year.Note: For other types of biochemical analysis, proceed to the appropriate treatment as follows.-

a.For chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-seq, crosslink the cell pellet using 1% formaldehyde solution for 10 min at room temperature. After centrifugation, washing the cell pellets with PBS, store at −80°C. We used 100,000 cells for H3K27me3 ChIP-seq (Kuwayama et al., 2020).

-

b.For assay for transposase-accessible chromatin (ATAC)-seq, proceed to the ATAC reaction without freezing cells (Yamanaka et al., 2020). For freezing before ATAC reaction, cryopreservation can provide data with better quality (Milani et al., 2016). We used 20,000 cells for ATAC-seq (Yamanaka et al., 2020).

-

c.For cleavage under targets and tagmentation (CUT&Tag), cryopreserve the cell pellet using cell stock solution, such as CELLBANKER (Takara). We can also directly sort the cells into the 1.5 mL tube, including cell stock solution in step 26. We used 10,000 cells for H3K27me3 and 100,000 cells for Ring1B CUT&Tag (Eto et al., 2020).

-

a.

Checking the cell fractions by RT-qPCR

Timing: 1 day

-

31.

Extract total RNA from the frozen cells with the use of RNAiso Plus and measure its concentration with an absorption photometer such as NanoDrop.

-

32.

Subject the total RNA to RT with a ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Master Mix with gDNA Remover and dilute the generated cDNA 5- to 10-fold with water.

Note: We perform steps 31 and 32 under RNase-free conditions.

Note: 100 ng of total RNA are sufficient for the RT-qPCR analysis.

Alternatives: RNA extraction and RT can also be performed with other reagents or kits such as TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), respectively.

-

33.

Prepare the following premix for qPCR.

| Reagent | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| THUNDERBIRD SYBR qPCR Mix | 50% (v/v) | 2.5 μl/reaction |

| Forward primer (100 μM) | 1.6 μM | 0.08 μl |

| Reverse primer (100 μM) | 1.6 μM | 0.08 μl |

| ddH2O | 0.34 μl | |

| Total | 3 μl |

CRITICAL: Given that we usually quantify the amount of target cDNA by generating a calibration curve and run a negative control sample consisting of water, it is necessary to make a premix for these samples.

-

34.

Add 3 μl of the premix followed by 2 μl of diluted cDNA to 8-stripe tubes or a 96-well plate, mix, and centrifuge briefly.

-

35.

Perform the qPCR reaction in a LightCycler 480 instrument according to a protocol described by the manufacturer of the SYBR reagent (https://www.toyobo-global.com/seihin/xr/lifescience/support/manual/QPS-201.pdf).

-

36.

Calculate the concentration of the target cDNA with LightCycler 480 software by absolute quantification.

CRITICAL: We always check that the calibration curve is appropriate, that the amplification efficiency is ~2.0, that the signal of the water sample is negligible, and that the melting temperature (Tm calling) curve has only one peak.

-

37.

Calculate the expression levels of the target genes with normalization to an internal control gene such as Gapdh.

Note:Actb is another suitable internal control gene.

Expected outcomes

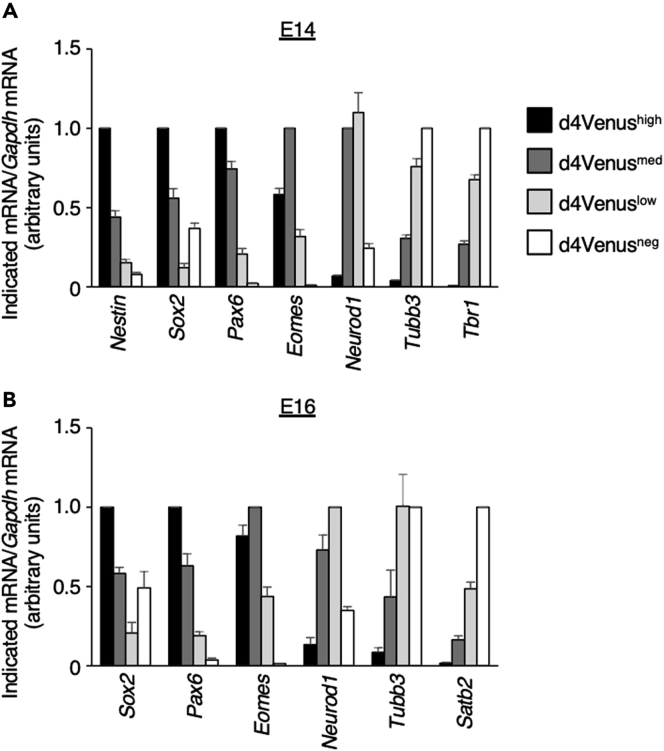

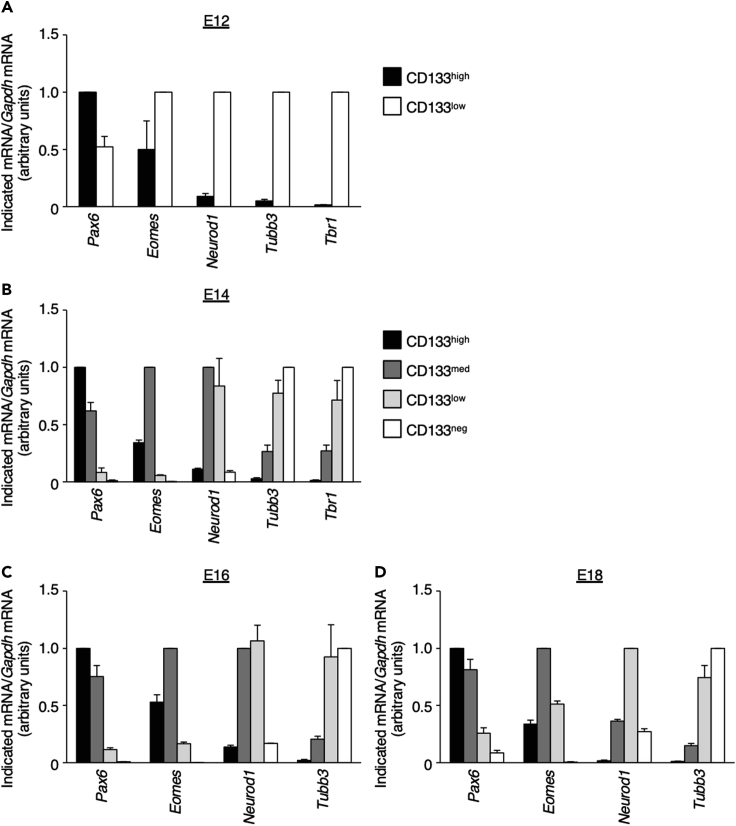

Successful cell sorting and RT-qPCR analysis should reveal the effect of an electroporated plasmid or changes in the expression of marker genes for neural progenitors or neurons at various differentiation stages. For example, introduction of a knockdown plasmid should result in an observed reduction in the amount of the target mRNA, such as was the case for knockdown of Hmga2 mRNA in a previous study (Sakai et al., 2019). Examples of results for neural progenitors and neurons isolated from the Nestin-d4Venus mouse neocortex or from the wild-type mouse neocortex stained with anti-CD133 at E12, E14, E16, or E18 are shown in Figures 3 and 4. Marker genes for neural progenitors—such as Nestin, Sox2, and Pax6—are highly expressed in d4Venushigh or CD133high fractions; those for immature neurons, such as Eomes and Neurod1, are highly expressed in d4Venus-medium (d4Venusmed) and d4Venuslow fractions or in CD133med and CD133low fractions; and those for neurons—such as Tubb3, Satb2, and Tbr1—are highly expressed in d4Venusneg or CD133neg fractions.

Figure 3.

Quality check for neural progenitors and neurons isolated from the neocortex of Nestin-d4Venus embryos

(A and B) Isolated d4Venus-high, -medium, -low, and -negative cells at E14 (A) or E16 (B) were subjected to RT-qPCR analysis of the indicated mRNAs. Data were normalized by the amount of Gapdh mRNA, expressed relative to the higher value for each mRNA, and are means + SEM from 11 (Sox2, Pax6, Eomes, Neurod1, Tubb3, and Tbr1 at E14) and four (E16 and Nestin at E14) independent experiments independent experiments with the exception of Nestin mRNA (four independent experiments).

Figure 4.

Quality check for neural progenitors and neurons isolated from the neocortex of wild-type embryos on the basis of CD133 staining

(A–D) Isolated CD133-high, -medium, -low, or -negative cells at E12 (A), E14 (B), E16 (C), or E18 (D) were subjected to RT-qPCR analysis of the indicated mRNAs. Data were normalized by the amount of Gapdh mRNA, are expressed relative to the higher value for each mRNA, and are means + SEM from three (E12, E18, and Pax6 and Tbr1 at E14) or four (E16 and Eomes, Neurod1, and Tubb3 at E14) independent experiments.

Limitations

Neuronal differentiation is a multistep process. For example, immediately after neuronal fate commitment of neural progenitors, Neurog1 and Neurog2 are expressed, with this expression being followed by that of Eomes and subsequently by that of Neurod1. However, whereas cell sorting based on CD133 or on Nestin-d4Venus expression can distinguish between Nestin-positive neural progenitors and Neurod1-positive immature neurons, most Neurog1- or Neurog2-positive cells are present in the CD133high fraction, and Eomes-positive cells are present in both CD133high and CD133med fractions (Figures 3 and 4). Separation of these cells thus requires the use of specific transgenic mice expressing a fluorescent protein under the control of promoters or enhancers of Neurog1, Neurog2, or Eomes (Arnold et al., 2009; Berger et al., 2004; Gong et al., 2003; Kara et al., 2015). Intracellular immunostaining of crosslinked neural cells for Eomes/Tbr2, Satb2, Ctip2, and Tle4 is another option (Molyneaux et al., 2015; Sakib et al., 2021), although crosslinking restricts the types of subsequent experiments,

Given that mature neurons possess many processes, they are vulnerable to enzymatic dissociation and are easily killed. This protocol is therefore applicable only to cells whose differentiation from neural progenitors has been underway for a few days. We have found that neurons differentiated from neural progenitors that were electroporated at E12 can be recovered efficiently up to E16, but hardly at all after E17— even when the fluorescence of transfected cells was clearly observed with a fluorescence stereomicroscope before dissociation (data not shown). Deep-layer neurons that have been undergoing differentiation for >5 days thus cannot be recovered after dissociation. Other methods, such as isolation of labeled nuclei with transgenic mice or staining for a neuronal nuclear marker, such as NeuN (Mo et al., 2015; Rehen et al., 2005; Spalding et al., 2005), are necessary to recover mature neurons for biochemical experiments.

We have here described the isolation of the most differentiated neurons as d4Venusneg or CD133neg cells. However, these populations also include nonneural cells of the embryonic neocortex such as hematopoietic cells. Indeed, RNA-sequencing analysis of d4Venus-high, -medium, -low, and -negative fractions from Nestin-d4Venus embryos at E14 revealed that the d4Venusneg population expressed hematopoietic genes at high levels (data not shown) (Sakai et al., 2019). For removal of such nonneural cells, staining of the differentiated neuronal marker CD24 together with that of CD133 is useful (Pruszak et al., 2009; Uchida et al., 2000). The nonneural cells are then eliminated as those negative for both CD24 and CD133 (Figure 2C). The CD133high fraction also contains endothelial cells, which we can eliminate by discarding cells positive for isolectin B4 (IB4), a marker for endothelial cells.

Troubleshooting

Problem 1

Frequent clogging of the FACS machine at step 26

Potential solution

Most clogging of the FACS machine is caused by the stickiness of genomic material released from dead cells during cell dissociation and staining. We find that centrifugation through a Percoll solution is useful for removal of such material before cell sorting. If genomic material is still observed after resuspension of stained cells (step 21), it can be removed with a pipette tip. It is also important that the Neuron Dissociation Solutions are used at room temperature.

Problem 2

Taking much time for sorting at step 26

Potential solution

Generally, a shorter time for dissection, dissociation, immunostaining, and sorting provides better quality of the analysis. The dissection of the electroporated region under fluorescence stereomicroscope as noted at step 2 is valid for shortening the sorting time.

Problem 3

No obvious cell pellet after centrifugation at step 28

Potential solution

In general, it is possible to visualize a pellet containing >10,000 cells. Given that cells are readily trapped on the walls of tubes, coating of the inner surface of collection tubes with BSA before addition of the cushion buffer is necessary to ameliorate this problem. Although commercially available low-binding tubes can be used for this purpose, coating with BSA is the best choice for prevention of cell trapping by the tube wall.

Problem 4

Low yield of RNA at step 31 or low signals in the other analysis than expected

Potential solution

In general, it is difficult to fully recover the cell number counted by the FACS machine after cell pelleting since the cells that die or become unhealthy during the sorting process cannot make the pellet by centrifugation. For reducing those cells, it is useful to mix the sheath and cushion solution immediately after sorting at step 27. It is also valid to count the cell number recovered after cell pelleting for checking recovering rate in each case.

Problem 5

Reads mapped to both genomic regions and electroporated plasmids after sequencing analysis

Potential solution

If electroporated plasmids contain the sequences from the mouse genome, corresponding reads are mapped to the genomic regions after RNA-seq, ChIP-seq, CUT&Tag, or ATAC-seq analyses and should be removed from the subsequent analysis.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Yusuke Kishi (ykisi@mol.f.u-tokyo.ac.jp).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique materials.

Data and code availability

The data in this paper are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Y. Harada for critical reading of the manuscript, H. Okano (Keio University) for Nestin-d4Venus transgenic mice, the One-Stop Sharing Facility Center for Future Drug Discoveries (The University of Tokyo) for performing FACS, and members of the Gotoh Laboratory for discussion. This research was supported by AMED-CREST (JP21gm1310004 to Y.G.), AMED-PRIME (JP21gm6110021 to Y.K.), MEXT/JSPS KAKENHI (JP16H06481, JP16H06479, and JP15H05773 to Y.G.; JP20H03179 and JP21H00242 to Y.K.) grants, the Uehara Memorial Foundation, Takeda Science Foundation, Daiichi Sankyo Foundation of Life Science, and SECOM Science and Technology Foundation.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Y.K. and Y.G.; methodology, Y.K.; investigation, Y.K.; writing, Y.K. and Y.G.; funding acquisition, Y.K. and Y.G.; supervision, Y.K. and Y.G.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Arnold S.J., Sugnaseelan J., Groszer M., Srinivas S., Robertson E.J. Generation and analysis of a mouse line harboring GFP in the Eomes/Tbr2 locus. Genesis. 2009;47:775–781. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger J., Eckert S., Scardigli R., Guillemot F., Gruss P., Stoykova A. E1-Ngn2/Cre is a new line for regional activation of Cre recombinase in the developing CNS. Genesis. 2004;40:195–199. doi: 10.1002/gene.20081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eto H., Kishi Y., Yakushiji-Kaminatsui N., Sugishita H., Utsunomiya S., Koseki H., Gotoh Y. The Polycomb group protein Ring1 regulates dorsoventral patterning of the mouse telencephalon. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:5709. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19556-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaiano N., Kohtz J.D., Turnbull D.H., Fishell G. A method for rapid gain-of-function studies in the mouse embryonic nervous system. Nat. Neurosci. 1999;2:812–819. doi: 10.1038/12186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong S., Zheng C., Doughty M.L., Losos K., Didkovsky N., Schambra U.B., Nowak N.J., Joyner A., Leblanc G., Hatten M.E. A gene expression atlas of the central nervous system based on bacterial artificial chromosomes. Nature. 2003;425:917–925. doi: 10.1038/nature02033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kara E.E., McKenzie D.R., Bastow C.R., Gregor C.E., Fenix K.A., Ogunniyi A.D., Paton J.C., Mack M., Pombal D.R., Seillet C. CCR2 defines in vivo development and homing of IL-23-driven GM-CSF-producing Th17 cells. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8644–8717. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwayama N., Kishi Y., Maeda Y., Nishiumi Y., Suzuki Y., Koseki H., Hirabayashi Y., Gotoh Y. In utero gene transfer system for embryos before neural tube closure reveals a role for Hmga2 in the onset of neurogenesis. bioRxiv. 2020;125 doi: 10.1101/2020.05.14.086330. 2020.05.14.086330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui A., Yoshida A.C., Kubota M., Ogawa M., Shimogori T. Mouse in utero electroporation: controlled spatiotemporal gene transfection. J. Vis. Exp. 2011 doi: 10.3791/3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon V., Thomas R., Ghale A.R., Reinhard C., Pruszak J. Flow cytometry protocols for surface and intracellular antigen analyses of neural cell types. J. Vis. Exp. 2014:e52241. doi: 10.3791/52241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milani P., Escalante-Chong R., Shelley B.C., Patel-Murray N.L., Xin X., Adam M., Mandefro B., Sareen D., Svendsen C.N., Fraenkel E. Cell freezing protocol suitable for ATAC-Seq on motor neurons derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:25474. doi: 10.1038/srep25474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo A., Mukamel E.A., Davis F.P., Luo C., Henry G.L., Picard S., Urich M.A., Nery J.R., Sejnowski T.J., Lister R. Epigenomic signatures of neuronal diversity in the mammalian brain. Neuron. 2015;86:1369–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molyneaux B.J., Goff L.A., Brettler A.C., Chen H.-H., Brown J.R., Hrvatin S., Rinn J.L., Arlotta P. DeCoN: Genome-wide analysis of in vivo transcriptional dynamics during pyramidal neuron fate selection in neocortex. Neuron. 2015;85:275–288. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruszak J., Ludwig W., Blak A., Alavian K., Isacson O. CD15, CD24, and CD29 define a surface biomarker code for neural lineage differentiation of stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2928–2940. doi: 10.1002/stem.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehen S.K., Yung Y.C., McCreight M.P., Kaushal D., Yang A.H., Almeida B.S.V., Kingsbury M.A., Cabral K.M.S., McConnell M.J., Anliker B. Constitutional aneuploidy in the normal human brain. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:2176–2180. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4560-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai H., Fujii Y., Kuwayama N., Kawaji K., Gotoh Y., Kishi Y. Plag1 regulates neuronal gene expression and neuronal differentiation of neocortical neural progenitor cells. Genes Cells. 2019;24:650–666. doi: 10.1111/gtc.12718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakib M.S., Sokpor G., Nguyen H.P., Fischer A., Tuoc T. Intranuclear immunostaining-based FACS protocol from embryonic cortical tissue. STAR Protocol. 2021;2:100318. doi: 10.1016/j.xpro.2021.100318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spalding K.L., Bhardwaj R.D., Buchholz B.A., Druid H., Frisén J. Retrospective birth dating of cells in humans. Cell. 2005;122:133–143. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunabori T., Tokunaga A., Nagai T., Sawamoto K., Okabe M., Miyawaki A., Matsuzaki Y., Miyata T., Okano H. Cell-cycle-specific nestin expression coordinates with morphological changes in embryonic cortical neural progenitors. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121:1204–1212. doi: 10.1242/jcs.025064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabata H., Nakajima K. Efficient in utero gene transfer system to the developing mouse brain using electroporation: visualization of neuronal migration in the developing cortex. Neuroscience. 2001;103:865–872. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuboi M., Kishi Y., Yokozeki W., Koseki H., Hirabayashi Y., Gotoh Y. Ubiquitination-Independent repression of PRC1 targets during neuronal fate restriction in the developing mouse neocortex. Dev. Cell. 2018;47:758–772.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida N., Buck D.W., He D., Reitsma M.J., Masek M., Phan T.V., Tsukamoto A.S., Gage F.H., Weissman I.L. Direct isolation of human central nervous system stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:14720–14725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viesselmann C., Ballweg J., Lumbard D., Dent E.W. Nucleofection and primary culture of embryonic mouse hippocampal and cortical neurons. J. Vis. Exp. 2011:e2373. doi: 10.3791/2373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka S., Kishi Y., Siomi H. ATAC-seq method applied to embryonic germ cells and neural stem cells from mouse: Practical tips and modifications. Epigenet. Methods. 2020;128:371–386. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-819414-0.00018-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data in this paper are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.