Abstract

Background & Aims:

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is associated with elevation of many cytokines particularly IL-6; however, the role of IL-6 in NAFLD remains obscure. The aim of this study was to examine how myeloid-specific IL-6 signaling affects NAFLD via the regulation of anti-fibrotic microRNA-223 in myeloid cells.

Approach & Results:

Patients with NAFLD or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and healthy controls were recruited, and serum IL-6 and soluble IL-6 receptor α (sIL-6Rα) were measured. Compared to controls, serum IL-6 and sIL-6Rα levels were elevated in NAFLD/NASH patients. IL-6 levels correlated positively with the number of circulating leukocytes and monocytes. The role of IL-6 in NAFLD was investigated in Il6 knockout (KO) and Il6 receptor A (Il6ra) conditional KO mice after high-fat diet (HFD) feeding. HFD-fed Il6 KO mice had worse liver injury and fibrosis, but less inflammation compared to WT mice. Hepatocyte-specific Il6ra KO mice had more steatosis and liver injury, whereas myeloid-specific Il6ra KO mice had lower number of hepatic infiltrating macrophages and neutrophils with increased cell death of these cells but greater liver fibrosis than WT mice. Mechanistically, the increased liver fibrosis in HFD-fed myeloid-specific Il6ra KO mice was due to the reduction of anti-fibrotic miR-223 and subsequent upregulation of the miR-223 target gene transcriptional activator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ), a well-known factor to promote NASH-fibrosis. In vitro, IL-6 treatment upregulated exosome biogenesis-related genes and subsequently promoted macrophages to release miR-223-enriched exosomes that were able to reduce pro-fibrotic TAZ expression in hepatocytes via exosomal transfer. Finally, serum IL-6 and miR-223 levels were elevated and correlated with each other in NAFLD patients.

Conclusions:

Myeloid-specific IL-6 signaling inhibits liver fibrosis via exosomal transfer of anti-fibrotic miR-223 into hepatocytes, providing novel therapeutic targets for NAFLD therapy.

Keywords: NAFLD, miR-223, TAZ, IL-6 receptor

Introduction

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most prominent cause of chronic hepatic disease worldwide.(1, 2) It represents a spectrum of disorders that ranges from simple steatosis to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.(3) Inflammation is generally believed to play a key role in the progression of NAFLD.(3–5) However, the exact effects of inflammation on NAFLD progression especially on liver fibrosis remain obscure.(4, 5)

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a pleiotropic cytokine with complex roles in inflammation, playing important roles in controlling the pathogenesis of all types of diseases, including NAFLD.(6–11) Elevated serum, hepatic, and adipose IL-6 levels in patients with NASH have been implicated in insulin resistance, steatosis, and liver injury.(6–12) IL-6 levels are also elevated in mice fed a high-fat diet (HFD), and genetic deletion of the Il6 enhanced HFD-induced steatosis and liver injury.(13) In contrast, deletion of the Il6 gene attenuated liver injury and inflammation in another model of NASH induced by feeding methionine and choline-deficient diet.(14) These contradictory data on the role of IL-6 in NAFLD were probably due to the different models used and widely expressed membrane bound IL-6 receptor α (mIL-6Rα) and its signaling chain gp130 as well as the existence of soluble IL-6R (sIL-6R) and soluble gp130 (sgp130).(15) Gp130 is ubiquitously expressed, while IL-6Rα expression is restricted largely to hepatocytes, megakaryocytes, and subsets of leukocytes.(15) Myeloid cells including macrophages and neutrophils express IL-6Rα and are key mediators of obesity-associated inflammation.(15) Although macrophages have been implicated in the pro-inflammatory phenotype in the early phase of NASH, they may adopt a restorative phenotype in the chronic resolution phases of liver disease to limit liver fibrosis.(16–18) The role of myeloid-specific IL-6 signaling in the control of NAFLD progression remains unknown.

IL-6 activates classic signaling via the binding of mIL-6Rα, resulting in gp130 dimerization and subsequent activation of Janus kinases (JAKs) and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3). Activated STAT3 leads to IL-6-dependent gene expression and cellular responses such as acute phase response, proliferation, migration, or metabolic changes.(15) IL-6 can also signals via the sIL-6R and gp130, which is known as trans-signaling and allows cells that do not express IL-6Rα to respond to IL-6.(19) IL-6-mediated trans-signaling has been shown to play a role in a variety of liver functions such as liver regeneration.(20) sIL-6R is previously considered as a systemic buffer system by promotingIL-6 trans-signaling via IL-6-sIL-6R.(19) However, a recent study suggests that IL-6-sIL-6R complex is formed much lower frequency than previously anticipated, suggesting that classic IL-6 signaling via the mIL-6R is active even under conditions where sIL-6R is in a high molar excess over IL-6.(21)

We have previously demonstrated that Il6 KO mice are more susceptible to liver injury and steatosis after 3-month HFD feeding.(13) However, liver fibrosis and hepatocarcinogenesis were not examined. In the current study, we subjected Il6 KO and WT mice to long-term (one year) HFD feeding and examined liver injury and cancer in these mice. The role of cell-specific IL-6 signaling in NAFLD was further examined in two lines of Il6 receptor a (Il6ra) conditional KO mice, including hepatocyte-specific (Il6raHep−/−) and myeloid-specific (Il6raMye−/−) KO mice. Of interest, Il6raMye−/− mice were more susceptible to liver fibrosis than WT mice after 3-month-HFD feeding despite less hepatic neutrophil and macrophage infiltration in the knockouts. We have identified a novel mechanism by which myeloid IL-6 signaling ameliorates HFD-induced liver fibrosis: IL-6 promoted macrophages to release miR-223 enriched exosomes that may get transferred into hepatocytes where they suppress the expression of several miR-223 target genes including transcriptional activator with PDZ-binding motif (Taz), NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (Nlrp3), C-X-C motif chemokine 10 (Cxcl10), which are known to promote NASH fibrosis.(22–26)

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are small membrane-bound vesicles released to the extracellular space by cells under both physiological and pathological conditions.(27) Based on their cellular biogenesis and sizes, EVs can be divided into three groups: exosomes (40 nm-150 nm diameter in size), microvesicles/microparticles (MPs, 50 nm-1,000 nm diameter), and apoptotic bodies (>500 nm in diameter).(28) Exosomes carry proteins, miRNAs, DNAs, and glycolipids, which upon delivery can affect the cellular functions of their recipient cells.(27) Recent studies have shown that lipotoxic hepatocytes produce exosomes, which can activate macrophages via the delivery of various contents including mitochondrial DNA and tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand.(29, 30) Hepatocyte-derived exosomes can also promote fibrosis resolution by inhibiting macrophage activation and cytokine secretion, by suppressing the activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), and by inducing extracellular matrix degradation and remodeling.(31) In addition, neutrophils and macrophages can also release exosomes that subsequently alter liver functions. For example, miR-223 is one of most abundant miRNAs expressed in neutrophils and macrophages, playing a key role in controlling inflammation in various types of diseases including liver diseases.(32) After activation, neutrophils can deliver miR-223 via exosomes into macrophages(33, 34) or hepatocytes,(35) thereby inhibiting NASH and liver fibrosis. Macrophages can also deliver miR-223 via exosomes into a variety of cells including hepatocytes where they subsequently affect the functions of these cells.(36, 37) In the current paper, we demonstrate that IL-6 can induce macrophages and also neutrophils, albeit to a lesser extent, to release miR-223-enriched exosomes, which are then transferred into hepatocytes to suppress liver fibrosis. Mechanistically, IL-6 promotes exosome biogenesis by upregulating exosome biogenesis-related genes without affecting pre-miRNA-223 expression.

Materials and Methods

Serum samples from NAFLD patients

A total of 40 patients with biopsy-proven NAFLD in this study were recruited from a well-characterized Prospective Epidemic Research Specifically Of NAFLD (PERSONS) cohort 1 from December 2016 to July 2019 (Supporting Table 1).(38) Forty age and sex matched healthy individuals were also enrolled as healthy controls (HCs). Cohort 2 patients include 50 NASH patients and 30 HCs (Supporting Table 2). The research protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University and Anhui Medical University. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject before the participation in the study.

Mice and HFD feeding mouse model

WT and Il6 global KO mice on a C57BL/6J background (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) at age 8–10 weeks were used. Hepatocyte-specific Il6ra KO (Il6raHep−/−) and myeloid-specific Il6ra KO (Il6raMye−/−) were generated by a few steps including crossing Il6raflox/flox mice with Albumin Cre and Lysosome Cre mice (Jackson Laboratory), respectively. The littermate Il6raflox/flox mice were used as WT controls. Mice were fed the HFD (60% kcal% fat; Research Diet, New Brunswick, NJ) or control diet (10% kcal% fat; Research Diet) for 3 months or 1 year. All mouse experiments were approved by the NIAAA Animal Care and Use Committee.

MiR-223 in situ hybridization

The detection of miR-223 in situ hybridization was performed as described previously.(35) Paraffin liver sections were hybridized with FAM-labeled miR-223 probe (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). U6 was used as for positive control, which suggested that the RNA was stable in the section (the image is not shown). Sheep anti-FAM-POD (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) was used after slide blocking. Tyramine signal amplification (TSA) kit (Perkin Elmer) was performed to amplify the signal. Meanwhile, the slides were stained with albumin (Novus Biologicals [catalog NBP1–32458], Centennial, CO) or F4/80 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology [catalog 70076], Danvers, MA), and DAPI. The images were obtained by using LSM 710 confocal microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the means ± SEM and were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software (La Jolla, CA). To compare values obtained from two groups, the Student t test was performed. To compare data from multiple groups, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was performed. Correlations between variables were assessed by linear regression analysis. The linear correction index R square and P values were calculated. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

Many other methods are described in supplemental materials.

Results

Elevation of serum IL-6 and sIL-6Rα levels in NAFLD and NASH patients

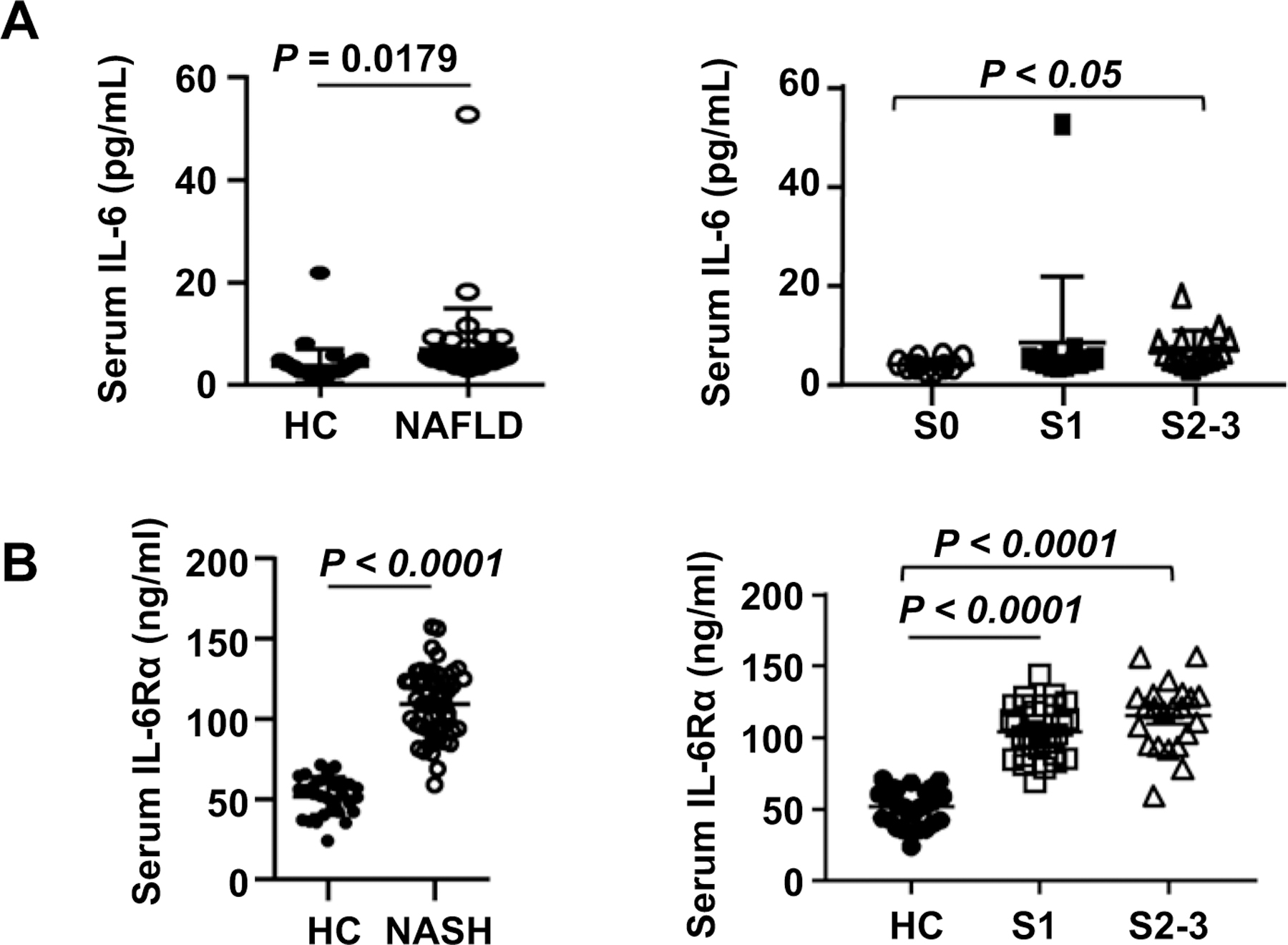

To investigate the role of IL-6 in the development of NAFLD, we first examined serum IL-6 levels in cohort 1 patients with NAFLD (Supporting Table S1) and heathy controls. As shown in Fig. 1A, serum IL-6 levels of NAFLD patients were significantly higher than those of heathy controls, and the patients with liver fibrosis (S1, S2–3) had higher serum IL-6 levels than did those without liver fibrosis (S0). Interestingly, IL-6 levels positively correlated with the number of circulating leukocytes and monocytes in NAFLD patients (Supporting Fig. S1A). There was a trend in the association between serum IL-6 levels and the number of neutrophils in NAFLD patients, but it did not reach statistical significance (Supporting Fig. S1A). IL-6 levels were independently associated with serum ALT and triglyceride levels in NAFLD patients (Supporting Fig. S1B).

Figure 1. Serum IL-6 and IL-6Rα levels in NAFLD patients.

(A) Serum samples of NAFLD patients (n=40) and healthy controls (n=40) were subjected to the measurement of IL-6. Serum IL-6 levels were compared between healthy controls and NALFD patients, and between those NAFLD patients without (S0) or with liver fibrosis (S1, S2–3). (B) Serum samples of NASH patients (n=50) and healthy controls (n=30) were subjected to the measurement of IL-6Rα levels. Serum IL-6Rα levels were compared between healthy controls and NASH patients, and between those NASH patients with liver fibrosis (S1, S2–3). Values represent means ± SEM.

We also used the cohort 2 patients with NASH to measure serum IL-6Rα levels (we were unable to measure serum IL-6 levels in this cohort due to limited amount of serum). As illustrated in Fig. 1B, NASH patients had significantly higher levels of serum IL-6Rα than healthy controls. Moreover, patients with grade S1 and S2–3 liver fibrosis had comparable levels of serum IL-6Rα, which were higher than those in healthy controls. IL-6Rα levels were independently associated with the number of circulating monocytes in NASH patients (Supporting Fig. S1C).

Il6 KO mice are more susceptible to long-term HFD-induced liver injury and fibrosis but are resistant to liver inflammation and tumor

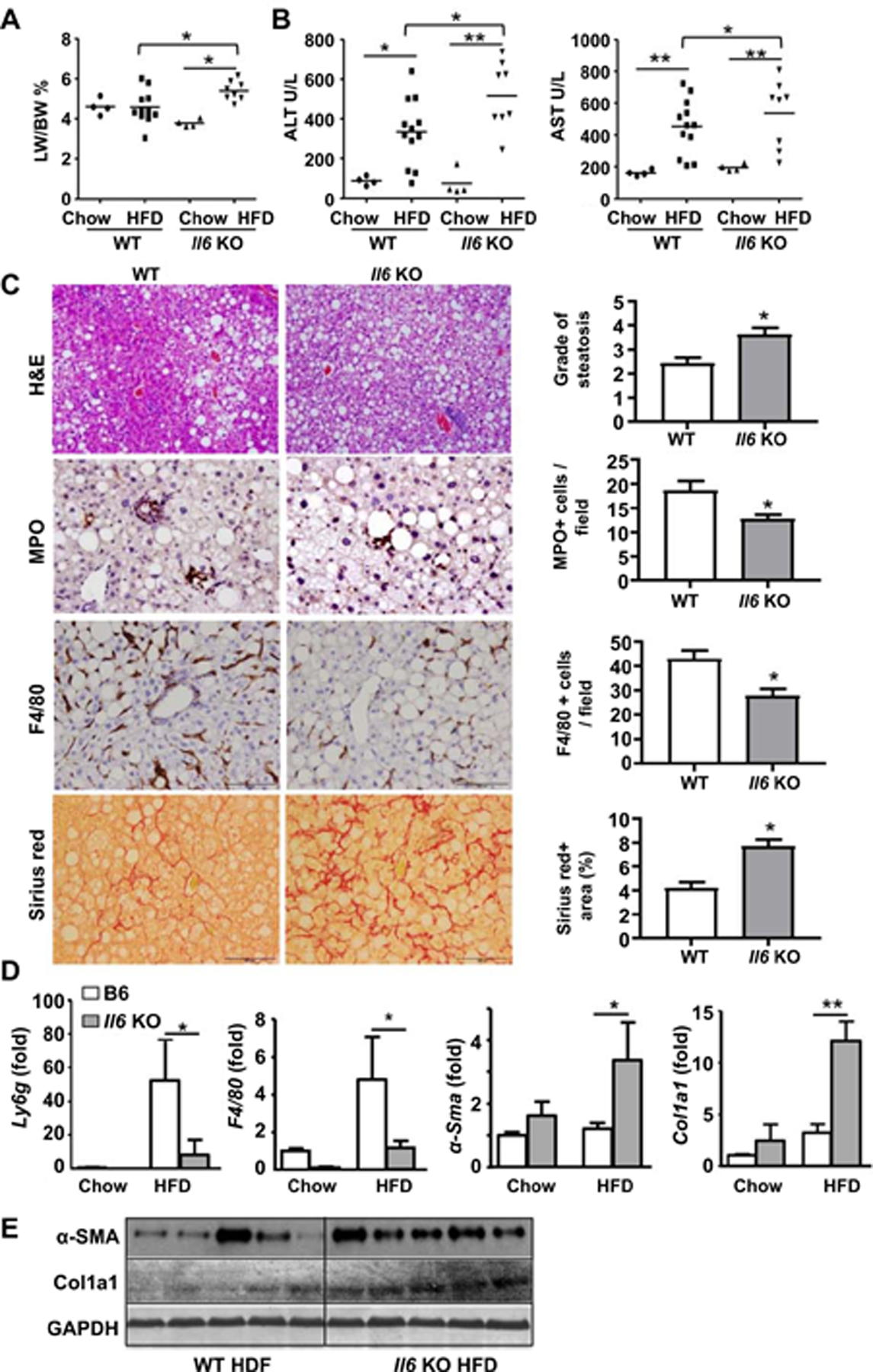

We have previously demonstrated that Il6 KO mice had greater liver injury and steatosis than WT mice after 3-month HFD feeding.(13) To further examine the role of IL-6 in long-term HFD-induced NASH, male Il6 KO and WT mice were fed an HFD and control diet for one year. Our data revealed that Il6 KO mice developed more severe phenotypes of NASH than WT mice after one-year HFD feeding, such as higher liver to body ratio, higher levels of serum ALT and AST (Fig. 2A and B, Supporting Fig. S2A), and greater steatosis (Fig. 2C). Despite greater liver injury, Il6 KO mice had decreased number of hepatic neutrophils and macrophages than WT mice (Fig. 2C), which was also confirmed by RT-qPCR analysis of hepatic Ly6g (neutrophil marker) and F4/80 (macrophage marker) mRNA levels (Fig. 2D). RT-qPCR analysis showed that compared to WT mice, Il6 KO mice had greater hepatic levels of steatogenic genes including acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase (Acc1), and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (Ppara) (Supporting Fig. S2B).

Figure 2. Il6 KO mice are more susceptible to one-year HFD-induced liver injury, steatosis, and fibrosis but resistant to liver inflammation.

WT and Il6 KO mice were fed an HFD or chow for one year. (A) Liver-to-body ratio and was measured. (B) Serum ALT and AST levels were measured. (C) Liver tissues were subjected to H&E staining, MPO and F4/80 immunostaining, and Sirius red staining. The quantitation of grade of steatosis, MPO+ and F4/80+ cells per field, and fibrotic area per field was determined, respectively. (D) RT-qPCR analyses. (E) Western blot analyses of α-SMA and Col1a1 expression in the liver. Values represent means ± SEM (n=4–12). *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01.

Next, we examined the role of IL-6 in liver fibrosis and hepatocarcinogenesis. As demonstrated in Fig. 2C–E, Il6 KO mice developed greater liver fibrosis than WT mice after one-year HFD feeding as determined by Sirius red staining, RT-qPCR analysis of hepatic α-sma, Col1a1 mRNAs, and western blotting analyses of fibrotic markers. In addition, both the tumor number and tumor size were lower in Il6 KO than in WT mice after feeding the HFD for one year (Supporting Fig. S2C–D). Finally, no difference was observed in glucose tolerance between Il6 KO and WT mice (Supporting Fig. S3). Additionally, serum levels of soluble IL-6Rα were not elevated in WT mice after HFD feeding (Supporting Fig. S4).

Il6raMye−/−mice have reduced infiltrating macrophages but not Kupffer cells compared with WT mice after 3-month HFD feeding

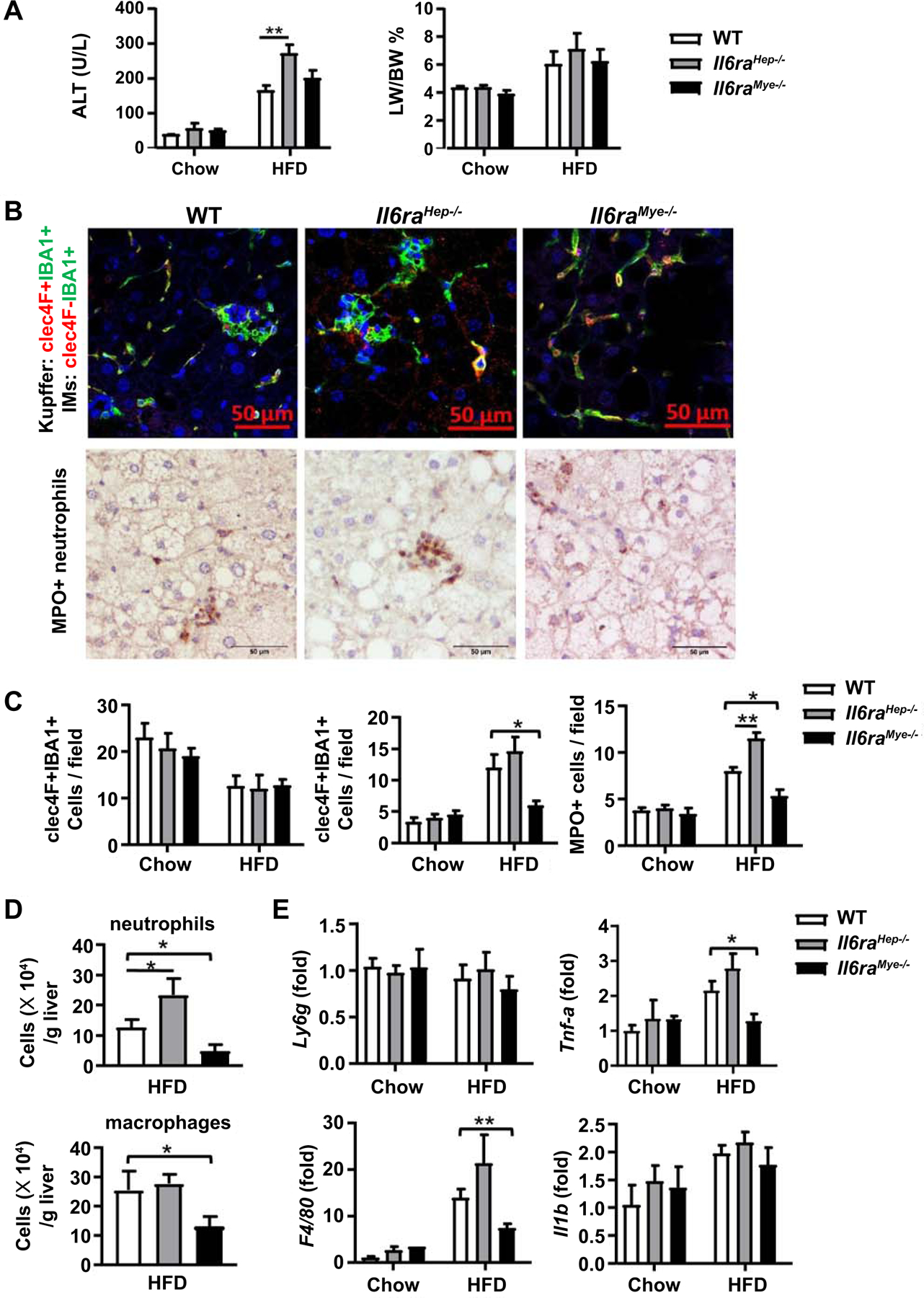

The above data show that Il6 KO mice are more susceptible to HFD-induced liver injury and steatosis but resistant to liver inflammation and cancer, suggesting that IL-6 signaling plays a protective role in hepatocytes but a detrimental role in immune cells. To further dissect the role of IL-6 in hepatocytes and myeloid cells, we generated Il6raHep−/−and Il6raMye−/−mice and fed these mice with the HFD and control diet for three months. As illustrated in Fig. 3A, Il6raHep−/−mice had higher serum levels of ALT compared to WT mice after HFD feeding. Similar to Il6 KO mice, Il6raHep−/−mice had a trend toward higher liver-to-body ratio than WT mice after HFD feeding although this did not reach statistical significance. H&E staining revealed that Il6raHep−/−mice had more hepatic steatosis than WT mice after HFD feeding (Supporting Fig. S5). Il6raMye−/− and WT mice had comparable levels of serum ALT, liver to body ratio, and hepatic steatosis after HFD feeding (Fig. 3A, Supporting Fig. S5).

Figure 3. Il6raMye−/− mice have a lower number of hepatic macrophages and neutrophils than WT mice after 3-month HFD feeding.

Il6raHep−/−mice, Il6raMye−/−mice, and WT mice were fed an HFD or chow for 3 months. (A) Serum ALT levels, and liver-to-body ratio were measured. (B) Immunofluorescence (top panels) and MPO staining in liver tissues from 3m-HFD-fed Il6raHep−/−mice, Il6raMye−/−mice, and WT mice. For immunofluorescence staining, anti-IBA-1 (green), anti-CLEC-4F (red) antibodies, and DAPI (blue) were used. (C) Quantification of CLEC-4F+IBA1+ Kupffer cells, CLEC-4F−IBA1+ infiltration macrophages, and MPO+ cells per field. (D) Flow cytometry analysis of hepatic neutrophils (CD45+CD11b+Ly6G+) and macrophages (CD45+CD11b+Ly6G−Ly6C+) numbers. (E) RT-qPCR analyses of hepatic Ly6g, F4/80, Tnfa, and Il1b expression. Values represent means ± SEM (n = 11–14). *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01 in comparison with WT HFD groups. IM: infiltrating macrophage.

Next, we studied liver inflammation by performing immunohistochemistry analyses of liver macrophages using antibodies against calcium binding adaptor molecule 1 (IBA-1) and C-Type Lectin Domain Family 4 Member F (CLEC-4F), which can distinguish liver resident Kupffer cells and infiltrating macrophages. Kupffer cells express both IBA-1 and CLEC-4F, while IMs that only express IBA-1.(39) As illustrated in Fig. 3B, C, in WT mice, the number of Kupffer cells (CLEC-4F+IBA-1+) was reduced, whereas the number of infiltrating macrophages (CLEC-4F−IBA-1+) was elevated after HFD feeding. Interestingly, HFD-fed Il6raMye−/−mice had much lower numbers of infiltrating macrophages in liver tissues compared with HFD-fed WT mice; whereas the number of Kupffer cells was comparable between these two groups. Furthermore, the number of infiltrating macrophages and Kupffer cells was comparable between Il6raHep−/−and WT mice. The number of myeloperoxidase-positive (MPO+) neutrophils was also lower in Il6raMye−/−mice but higher in Il6raHep−/− mice than WT mice post HFD feeding (Fig. 3B, C). In addition, flow cytometric and RT-qPCR analyses also confirmed that HFD-fed Il6raMye−/−mice had a lower number of macrophages (CD11b+F4/80+) (Fig. 3D) and lower hepatic expression of macrophage marker F4/80 and its associated cytokine Tnfa expression (Fig. 3E). The number of neutrophils (CD11b+Gr-1+) was also lower in HFD-fed Il6raMye−/−mice than in HFD-fed WT mice (Fig. 3D); whereas the expression of neutrophil marker Ly6g was comparable between these two groups (Fig. 3E). The gating strategy and percentages of hepatic granulocytes (Gr-1+CD11b+) and monocytes (CD11b+F4/80+) are shown in Supporting Fig. S6A, B.

Il6raMye−/−mice have increased death of hepatic infiltrating macrophages and neutrophils compared with WT mice after 3-month HFD feeding

To understand the molecular mechanisms by which Il6raMye−/−mice had lower number of liver infiltrating macrophages and neutrophils than WT mice after HFD feeding, we first checked the number of circulating monocytes and neutrophils, and hepatic levels of chemokines that promote infiltrating macrophage recruitment. As illustrated in Supporting Fig. S7A, the total number of circulating monocytes and neutrophils were comparable between chow-fed and HFD-fed groups, and between three HFD-fed groups of mice. Hepatic expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (Mcp-1), a key chemokine for infiltrating macrophage recruitment, was equal between the three groups of mice (Supporting Fig. S7B). Hepatic expression of macrophage inflammatory protein (Mip)-1a and Mip-1b was higher in the HFD-fed Il6raMye-/ and Il6raHep−/−mice than in HFD-fed WT mice, but no difference was observed between KO groups (Supporting Fig. S7B). Next, we examined the death of liver infiltrating macrophages and neutrophils by flow cytometric analysis and found that HFD-fed Il6raMye−/−mice had a significantly higher number of dead neutrophils and infiltrating macrophages stained with Zombie dye compared with those in HFD-fed WT mice (Supporting Fig. S7C).

Il6raMye−/−are more susceptible to 3-month HFD-induced liver fibrosis

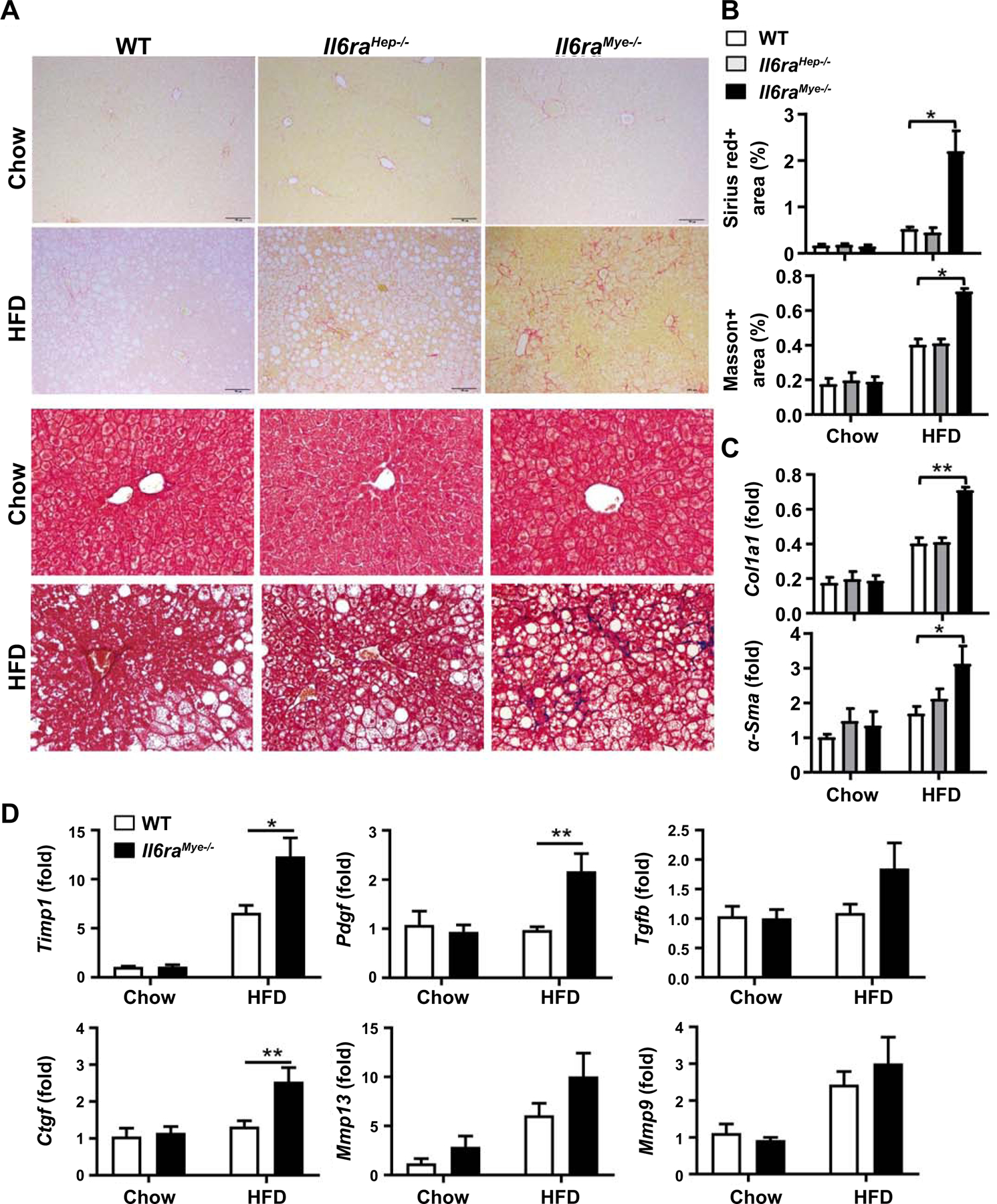

Previous studies showed that hepatic infiltrating macrophages promote steatosis and fibrosis in NASH,(40) which are mediated by producing pro-inflammatory genes, chemokines, and pro-fibrotic mediators.(17) Surprisingly, we found that despite of less liver inflammation, HFD-Il6raMye−/−mice developed greater liver fibrosis compared with WT mice, which was demonstrated by Sirius red staining, Masson staining (Fig. 4A and 4B), and RT-qPCR analyses of fibrogenic markers (Col1α1, α-Sma, Timp, Ctgf, and Ptgf) (Fig. 4C and 4D). In addition, we confirmed that mIL-6Rα expression was depleted on myeloid cells from Il6raMye−/−mice (Supporting Fig. S8).

Figure 4. Il6raMye−/− mice are more susceptible to liver fibrosis after 3-month HFD feeding.

Il6raHep−/−mice, Il6raMye−/−mice, and WT mice were fed an HFD or chow for 3 months. (A) Representative images of Sirius red staining (upper two panels) and Masson staining (lower two panels) of liver tissue sections are shown. (B) Quantification of fibrotic area per field. (C, D) RT-qPCR analyses of hepatic fibrogenesis genes. Values represent means ± SEM (n = 11–14). *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01 in comparison with WT HFD groups.

Il6raMye−/−mice have lower miR-223 levels in hepatocytes with elevated hepatic expression of miR-223 target genes than WT mice after 3-month HFD feeding

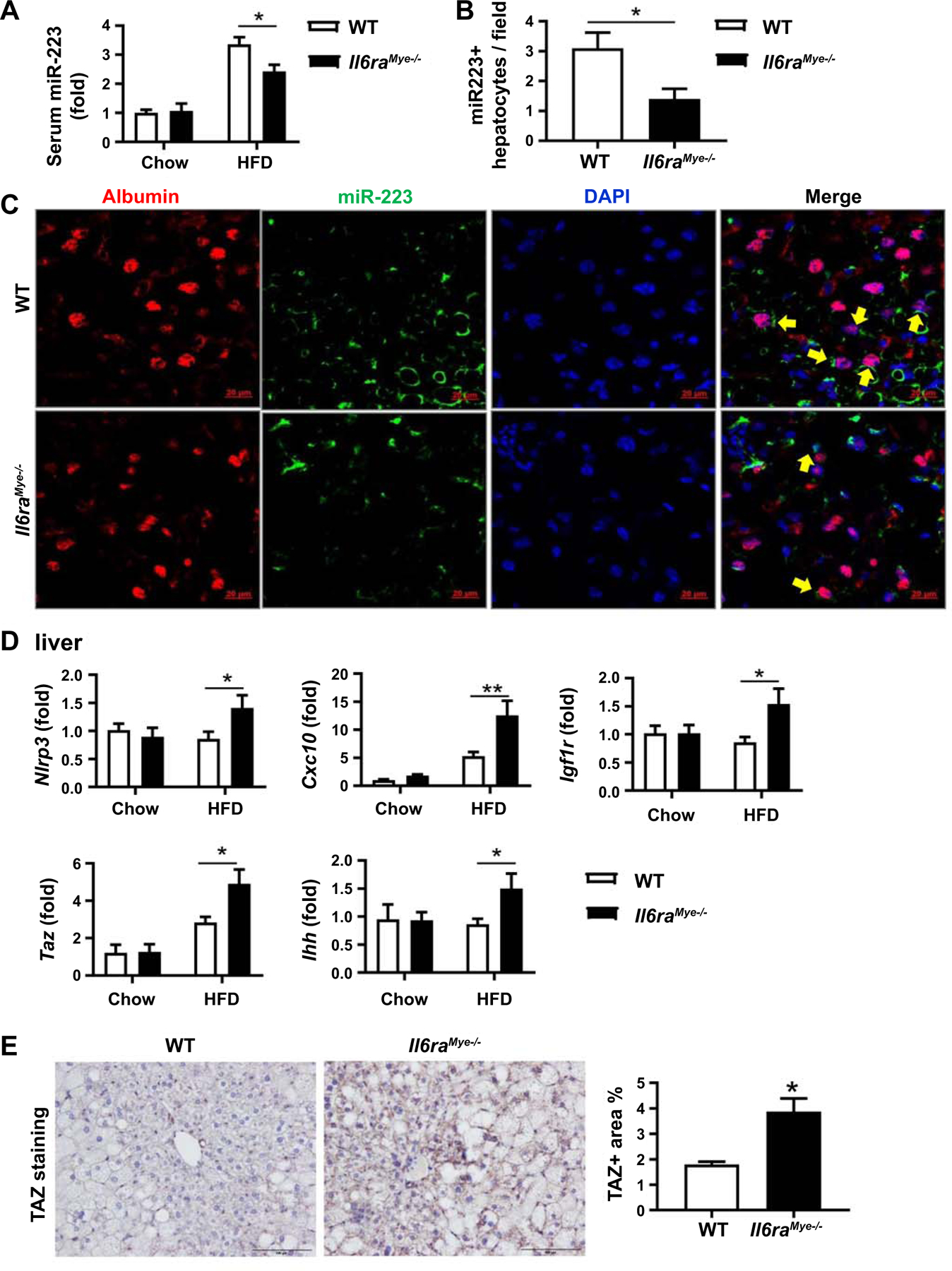

MiR-223 is a well-documented anti-fibrotic molecule that ameliorates liver fibrosis by inhibiting Cxcl10 and Taz expression in hepatocytes (35) and by inhibiting inflammasome NLRP3 in macrophages.(34) To explore the molecular mechanisms underlying the enhanced liver fibrosis in Il6raMye−/−mice, we examined serum and hepatic miR-223 levels in HFD-fed WT and Il6raMye−/−mice, and found that HFD feeding elevated serum miR-223 levels in both WT and Il6raMye−/−mice with much lower levels in the latter group than the former group (Fig. 5A). RT-qPCR analyses found that hepatic miR-223 levels were comparable between HFD-fed WT and Il6raMye−/− mice (Supporting Fig. S9). To better define miR-223 expression in the liver, we employed a more sensitive detection method by performing in situ hybridization analyses of miR-223 and immunofluorescent staining of the hepatocyte marker albumin or the macrophage marker F4/80. We found that the majority of F4/80+ macrophages were co-stained with miR-223, which was similar between HFD-fed WT mice and Il6raMye−/− (Supporting Fig. S10). In contrast, only 40% of albumin+ hepatocytes were co-stained with miR-223, which was further decreased in HFD-fed Il6raMye−/−mice (Fig. 5B–C). In agreement with the reduced hepatic miR-223 levels in Il6raMye−/−mice, hepatic expression of miR-223 targeted genes including Nlrp3, Cxcl10, Taz, and Igf1r was higher in HFD-fed Il6raMye−/−mice compared with HFD-fed WT mice (Fig. 5D). In addition, the Indian hedgehog (Ihh), which is a target of Taz that promotes the expression of pro-fibrotic genes,(22) was also upregulated in HFD-fedIl6raMye−/−mice compared to HFD-fed WT mice (Fig. 5D). Higher levels of hepatic TAZ in HFD-fed Il6raMye−/−mice versus WT mice were also confirmed by immunohistochemistry analysis (Fig. 5E).

Figure 5. Levels of miR-223 are lower while its targeted genes are higher in hepatocytes of Il6raMye−/−mice than those in WT mice after 3-month HFD feeding.

Il6raMye−/−mice and WT mice were fed an HFD for 3 months. (A) Serum samples were subjected to the measurement of miR-223 by RT-qPCR. (B, C) Frozen liver tissue sections were subjected to miR-223 in situ hybridization along with immunofluorescence staining of hepatocyte marker albumin. The percentage of miR-223+ hepatocytes is shown. (B). Representative images of albumin (red), miR-223 expression (green), and nuclei (blue) are shown (C). (D) RT-qPCR analyses of liver Nlrp3, Cxcl10, Taz, Igf1r, and Ihh levels in chow and 3-month HFD-fed mice. (E) Paraffin-embedded liver tissues were subjected to immunohistochemistry analyses. Representative TAZ staining of liver tissue sections and TAZ+ area per field was quantified. Values represent means ± SEM (n = 11–14). *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01 in comparison with WT HFD groups.

IL-6 promotes palmitic acid (PA) induction of miR-223 enriched exosomes by upregulating exosome biogenesis gene expression in mouse macrophages

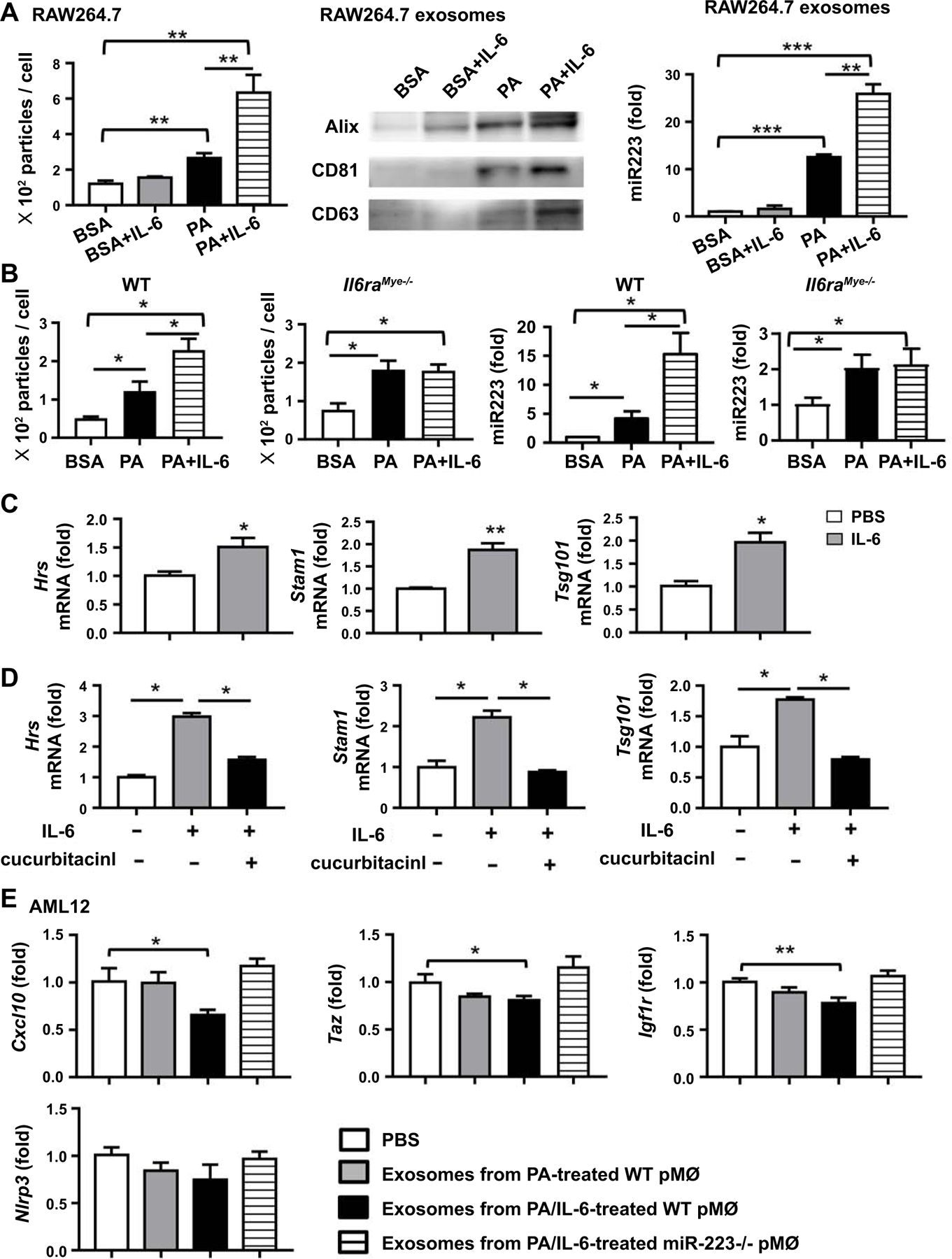

MiR-223 is the most abundant miRNA in neutrophils and macrophages but very low in hepatocytes.(41) miR-223 can be transported from myeloid cells to target cells though exomes and is functionally active.(37, 42) The above data revealed that serum miR-223 levels were lower in HFD-fed Il6raMye−/−mice compared to WT mice, suggesting that IL-6 signaling in myeloid cells stimulates miR-223 release from these cells. To confirm this notion, we first examined the effect of IL-6 on exosome release in RAW264.7 macrophages with or without PA stimulation. Exosomes in the supernatant from IL-6 and/or PA-treated myeloid cells were isolated using an exosome isolation kit and analyzed by nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) and western blot using antibodies against exosomal marker proteins. As shown in Fig. 6A, PA treatment markedly increased exosome secretion in RAW264.7 cells, which was further markedly enhanced by addition of IL-6. Without PA, IL-6 did not increase exosome release of RAW264.7 cells compared to BSA stimulation. Western blot analysis revealed that the amounts of exosome marker proteins, including CD63, ALIX, and CD81, were increased in the exosomes released from PA plus IL6-stimulated RAW264.7 cells compared with those from PA-stimulated RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 6A). Then we examined miR-223 levels in RAW264.7 cells released exosomes. We found that exosomes from PA+IL6-stimulated RAW264.7 cells had the highest levels of miR-223, which is about 25-fold higher than those from BSA-stimulated RAW264.7 cells, and about 2-fold higher than those from PA-stimulated RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, we examined exosome release and miR-223 levels in primary macrophages and neutrophils. In consistent with the findings in RAW264.7 cells, IL-6 treatment enhanced exosome release and miR-223 levels in these exosomes from PA-treated primary macrophages from WT mice but not from Il6raMye−/−mice (Fig. 6B). IL-6 also augmented exosome release from PA-treated neutrophils from WT mice but not from Il6raMye−/−mice (Supporting Fig. S11). Interestingly, IL-6 treatment did not affect miR-223 levels in exosomes from PA-treated neutrophils (Supplementary Fig. S11).

Figure 6. IL-6 promotes mouse macrophages to produce miR-223 enriched exosomes, which can inhibit miR-223-targeted genes in hepatocytes.

(A) RAW264.7 cells were stimulated with BSA (10%), BSA (10%)/IL-6 (100 ng/ml), PA (8 mM), or PA (8 mM)/IL-6 (100 ng/ml) for 24 hours. Exosomes isolated from supernatants were analyzed by nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) (left panel), western blot (middle panel), and RT-qPCR (right panel). (B) Peritoneal macrophages from WT mice and Il6raMye−/−mice were simulated with BSA (10%), BSA (10%)/IL6 (100 ng/ml), PA (8 mM), or PA (8 mM)/IL-6 (100 ng/ml) for 24 hours. Exosomes isolated from supernatants were examined by NTA and RT-qPCR. (C, D) RAW264.7 cells were treated with IL-6 (100 ng/ml) for 6 hours, and subsequently subjected to RT-qPCR analyses of the genes associated with exosome biogenesis (Hrs, Stam1, Tsg101). STAT3 inhibitor cucurbitacinl was included in the experiments in panel D. (E) AML12 cells were treated with exosomes from PA- or PA/IL-6-treated WT peritoneal macrophages or PA/IL-6-treated miR-223 KO peritoneal macrophages respectively. After 24 hours, AML12 cells were subjected to RT-qPCR analysis of Nlrp3, Cxcl10, Taz, and Igf1r.Values represent means ± SEM from three or four independent experiments. *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01 in comparison with PBS-treated group.

To determine the mechanism by whichIL-6 enhances exosome release, we examined the effect of IL-6 on the expression of several genes associated with intracellular vesicle trafficking (Rab5b, Rab7a, Rab27a, Rab11b, and Rab35) and genes associated with exosome biogenesis (Hrs, Stam1, Tsg101, Vta1, Ykt6, and nsmase2).(43) As illustrated in Fig. 6C, IL-6 treatment upregulated the expression of genes associated with exosome biogenesis, such as Hrs, Stam1, and Tsg101 but it did not affect the expression of Rab5b, Rab11b, Rab27a, Vta1, Nsmase 2 (Supporting Fig. S12A). Furthermore, we treated RAW264.7 cells with IL-6 in combination with the STAT3 inhibitor cucurbitacinl and found co-treatment with this inhibitor significantly reduced Hrs, Stam1, and Tsg101 expression levels (Fig. 6D), suggesting IL-6 upregulates the expression of exosome biogenesis genes dependent on STAT3, a key downstream signaling of IL-6. In addition, expression of miR-223 and primary miR-223 (pri-miR-223) in RAW264.7 cells were decreased after IL-6 treatment (Supporting Fig. S12B), suggesting that IL-6 does not increase rather than decreases miR-223 gene expression in mouse macrophages.

We next examined whether myeloid cell-derived miR233 enriched exosomes suppressed the expression of miR-223 targeted genes in hepatocytes. Exosomes from PA/IL-6-treatedWT peritoneal macrophages inhibited the expression of miR-223 targeted genes including Cxcl10, Taz, and Igf1r, in AML12 cells, while exosomes from PA/IL-6-treated miR-223−/−peritoneal macrophages did not (Fig. 6E).

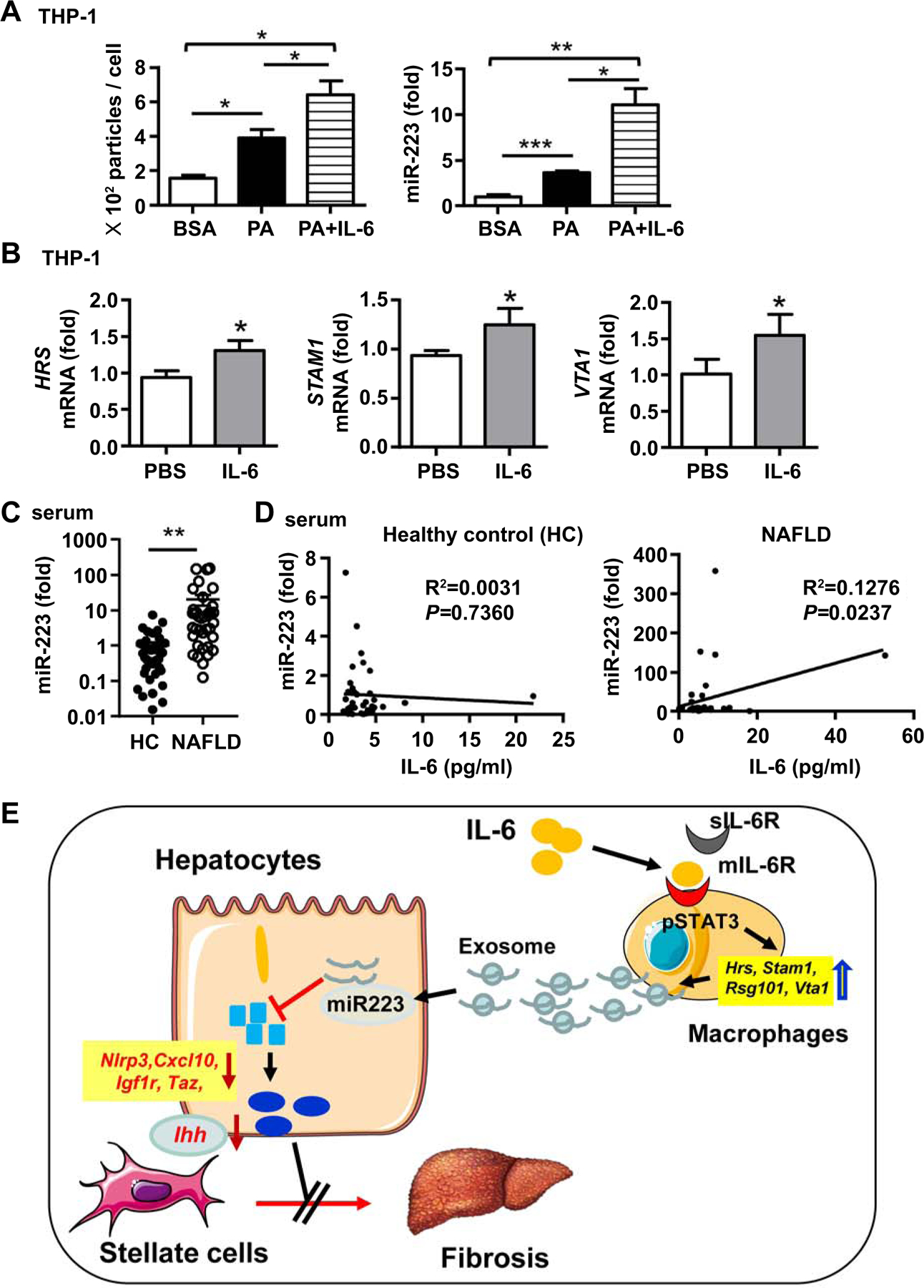

IL-6 promotes PA induction of miR-223 enriched exosomes in human macrophages, and its levels correlate positively with miR-223 levels in the serum of NAFLD patients

In consistent with the above findings, IL-6 treatment also enhanced human THP-1 monocytes to release exosomes and miR-223 with PA stimulation (Fig. 7A). In addition, IL-6 treatment increased the expression of genes associated with exosome biogenesis (Hrs, Stam1, and Vta1) (Fig. 7B) without affecting Tsg101, Nsmase2, Rab11b, Rab5b, and Rab27ain THP-1 cells (Supporting Fig. S12C). Next we examined the relationship between IL-6 and miR-223 in NAFLD patients and found that serum miR-223 levels were significantly higher in NAFLD patients than in heathy controls (Fig. 7C). Interestingly, serum IL-6 levels correlated positively with serum levels of miR-223 in NAFLD patients but not in healthy controls (Fig. 7D).

Figure 7. IL-6 promotes miR-223 enriched exosome production in human monocytic cells.

(A) THP-1 cells were simulated with BSA (10%), PA (8mM), or PA (8mM)/IL-6(100 ng/ml) for 24 hours. Exosomes isolated from supernatants were analyzed by NTA (left panel). miR-223 levels in exosomes were analyzed by RT-qPCR (right panel). (B)THP-1 cells were simulated withIL-6for 6 hours. The expression levels of genes associated with exosome biogenesis (Hrs, Stam1, Tsg101, Vta1) were examined by RT-qPCR. (C, D) Serum samples of NAFLD patients (n=40) from the cohort 1 and healthy controls (n=40) were subjected to the measurement of miR-223 (panel C). Correlation between serum IL-6 and miR-223 levels in NFLD patients and healthy controls (HC) (panel D). Values represent means ± SEM. *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01, **P< 0.001. (E) Model depicting the critical role of macrophage-specific IL-6 signaling in controlling of liver fibrosis by promoting macrophages to release miR-223-enriched exosomes that inhibit the expression of several miR-223-targeted genes in hepatocytes, thereby attenuating liver fibrosis.

Discussion

NASH patients are characterized by significant inflammation and steatosis in the liver with elevated plasma levels of many cytokines particularly IL-6.(6–12) Plasma IL-6 levels were reported to be increased in NASH patients, which correlated with the disease severity.(7, 12) However, the complex role of IL-6 in the progression of NAFLD is not fully understood. In the current study, we found that serum IL-6 levels were elevated and correlated positively with the number of leukocytes and monocytes in the blood of NAFLD patients but did not correlate with serum ALT and triglyceride levels. Moreover, we also found that NAFLD patients with fibrosis (S1, S2–S3) had a higher level of IL-6 than did those without fibrosis (S0). The elevated plasma IL-6 in NAFLD patients is likely derived from several cell types including fibroblasts, monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, and hepatocytes because all of them have been reported to produce IL-6.(6–12) Furthermore, we demonstrated that Il6 KO and Il6raMye−/−mice showed decreased inflammation but increased fibrosis after HFD feeding, suggesting that IL-6 signaling in myeloid cells acts as an anti-fibrotic signal. sIL-6R is mainly produced by hepatocytes and myeloid cells which are responsible for approximately 60% and 40% of circulating sIL-6R, respectively.(44) Specific deletion of Il6ra in myeloid cells (Il6raMye−/−mice) completely ablated mIL-6R expression in myeloid cells but only partially reduced circulating sIL-6R by 40%.(44) The remained sIL-6R is derived from hepatocytes and may still partially activate IL-6 trans-signaling in myeloid cells in Il6raMye−/−mice. Therefore, the real anti-fibrotic role of myeloid IL-6 signaling is probably more significant than the phenotype we observed in Il6raMye−/−mice. Additionally, we found that serum sIL-6Rα levels were approximately 2-fold higher in NASH patients compared to healthy controls although this elevation was not observed in mice with 3-m or 6-m HFD feeding. The elevated sIL-6Rα in NASH patients may increase IL-6 trans-signaling in myeloid cells and play an important role in controlling liver fibrosis. Mechanistically, we provided evidence suggesting that IL-6 promotes myeloid cells to release miR-223-enriched exosomes which are then transferred into hepatocytes to suppress hepatic expression of miR-223 target pro-fibrotic genes, including Taz, Nlrp3, Cxcl10, Igf1r, thereby inhibiting NAFLD-associated liver fibrosis (Fig. 7E).

Our data show that Il-6KO mice had reduced numbers of infiltrating macrophages and neutrophils than WT mice after HFD feeding, and that similar changes were observed in myeloid-specific Il6raMye−/−mice after HFD feeding. Increased death of infiltrating macrophages and neutrophils was observed in Il6raMye−/−mice compared to WT mice, which is not surprising because IL-6 is a well-known survival factor for immune cells.(15) However, it was unexpected and interesting that the number of infiltrating macrophages but not liver resident Kupffer cells was reduced in HFD-fed Il6raMye−/−mice. These data suggest that IL-6 signaling plays an important role in promoting the survival of infiltrating macrophages but not Kupffer cells. The molecular mechanisms behind this interesting difference are not clear. Because Kupffer cells are long-lived cells, they probably do not need IL-6 signaling for survival.

It is generally accepted that inflammation promotes fibrosis and liver disease progression.(5, 45) Interestingly, our data showed that Il6 KO and Il6raMye−/−mice had fewer hepatic infiltrating macrophages and neutrophils but increased liver fibrosis after HFD feeding. Macrophages have been shown to respond to lipid insults by producing pro-inflammatory mediators and matrix-degrading enzymes that putatively regulate NAFLD.(45) These mediators include TGF-β, MMP2, MMP7, MMP9, MMP12, and MMP13 etc. Interestingly, the hepatic expression of Tgfb, Mmp9, Mmp13 was comparable in HFD-fed WT and Il6raMye−/−mice, suggesting that these mechanisms may not contribute to the increased liver fibrosis in Il6raMye−/−mice after HFD feeding. Instead, we provided some evidence suggesting that decreased miR-223 in hepatocytes might contribute to the increased liver fibrosis in HFD-fed Il6raMye−/−mice. First, normal hepatocytes express miR-223 at very low levels, which are markedly elevated after HFD feeding, and such miR-223 elevation has been suggested to ameliorate liver fibrosis by inhibiting TAZ expression in hepatocytes. (35) Second, although RT-qPCR analyses of whole liver tissue revealed comparable levels of miR-223 expression between HFD-fed Il6raMye−/− and WT mice, which is likely due to high levels of miR-223 expression in macrophages in the liver, as sensitive in situ hybridization analyses demonstrated that miR-223 expression was markedly reduced in the hepatocytes from HFD-fed Il6raMye−/− mice compared to WT mice. Consistently, hepatic expression of miR-223 target genes including pro-fibrotic genes Taz, Nlrp3, and Cxcl10, (22–25) was upregulated in HFD-fed Il6raMye−/− mice compared to WT mice. Collectively, downregulation of miR-223 and subsequent upregulation of the pro-fibrotic genes targeted by miR-223 in hepatocytes likely contribute to the increased liver fibrosis in HFD-fed Il6raMye−/− mice compared to WT mice. This conclusion could be further supported by a rescue experiment to see whether overexpression of miR-223 in hepatocytes reverses the phenotype by reducing liver fibrosis in HFD-fed Il6raMye−/− mice. Although we did not perform this rescue experiment, an elegant study previously reported that injection of the synthetic miR-223 3p markedly ameliorated liver fibrosis in a mouse model of NASH,(46) and we also demonstrated that overexpression of miR-223 in the liver significantly reduced liver fibrosis induced by chronic CCl4 treatment (Supporting Fig. S13). Thus, it is plausible that rescuing miR-223 expression likely reduces liver fibrosis in HFD-fed Il6raMye−/− mice.

In the current study, we found miR-223 was decreased in the serum and hepatocytes of Il6raMye−/−mice compared with WT mice after HFD feeding. This reduction was likely due to decreased exosomal miR-223 transfer because pre-miRNA-223 expression was not decreased in hepatocytes of Il6raMye−/−mice (data not shown) and it is well-known that miR-223 can be transferred from macrophages and neutrophils to other types of cells.(33–37) Furthermore, our data showed that with the stimulation of PA, IL-6 promotes both macrophages and neutrophils to release miR-223 enriched exosomes with a lesser extent in neutrophils. Coculture of these exosomes from WT but not miR-223 KO macrophages attenuated miR-223 targeted genes including Taz, Cxcl10, and Igf1r in hepatocytes, suggesting that this exosome transfer with miR-223 is functional. Collectively, our data suggest that IL-6 signaling in macrophages and neutrophils play an important role in promoting the release of miR-223-enriched exosomes, which are subsequently transferred into hepatocytes and provide a protective mechanism in controlling NASH progression.

The release of exosomes involves three steps: the formation of intraluminal vesicles in multi vesicular bodies (MVB), the transport of these MVBs to the plasma membrane and their fusion with the plasma membrane.(43) The endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) machinery is important in exosome biogenesis, and contains ESCRT-0 proteins (HRS and TSG101), ESCRT-I protein (STAM1), ESCRT-III proteins (CHMP4C, VPS4B, VTA1 and ALIX), and the associated AAA ATPase Vps4 complex.(47) Besides ESCRT proteins, tetraspanins (Tspan8, CD9, CD82, and CD63), lipopolysaccharide induced TNF factor (LITAF), and neutral sphingomyelinase 2 (nSMase2) play a role in exosome formation. Several Rab GTPases (Rab2b, Rab5a, Rab9a, Rab11, Rab27a, and Rab27b) have been shown to play a role in transporting of MVBs to the plasma membrane and exosome release.(43) Our data show that IL-6 treatment upregulates the expression of several ESCRT-related genes in mouse and human macrophages without affecting exosome trafficking related proteins. Inhibiting STAT3, a major downstream signal of IL-6, abolished IL-6 upregulation of ESCRT-related genes in macrophages. These data suggest that IL-6 may enhance exosome biogenesis in an STAT3-dependent manner without affecting exosome release.

In summary, we have identified a protective role for myeloid specific IL-6 signaling in limiting NAFLD-associated liver fibrosis and have defined a previously unknown mechanism whereby IL-6 induces myeloid cells to release miR-223-enriched exosomes which are then transferred to hepatocytes. This may set the stage for investigating IL-6 signaling in myeloid cells as a therapeutic strategy for the treatment of NASH.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support:

This study was supported in part by the National Nature and Science Foundation of China grants (81770588 to HW) and by the intramural program of the NIAAA, NIH, USA (BG). Dr. Xin Hou was supported by the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University Training Foundation when she performed experiments of mouse models at the NIAAA during 2018–2019. Shi Yin was a participant in the NIH Graduate Partnerships Program and a graduate student in the Anhui Medical University when she worked on this project during 2008–2011, and was affiliated with the Anhui Medical University and the NIH Graduate Partnerships Program.

Abbreviations:

- Acc1

acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CLEC-4F

C-Type Lectin Domain Family Member F 4

- CXCL10

C-X-C motif chemokine 10

- ESCRT

endosomal sorting complexrequired for transport

- HC

healthy control

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- HFD

high-fat diet

- HSC

hepatic stellate cell

- IBA-1

ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1

- Ihh

Indian hedgehog

- IL6raHep−/−

hepatocyte-specific Il6ra KO

- Il6raMye−/−

myeloid-specific Il6ra KO

- IM

infiltrating macrophages

- KO

knockout

- MCP1

monocyte chemoattractant protein 1

- Mip

macrophage inflammatory protein

- miR-223

microRNA-223

- MMP

matrix-degrading metalloproteinase enzymes

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- NAFLD

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- NLRP3

NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3

- PA

palmitic acid

- PPARα

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha

- TAZ

transcriptional activator with PDZ-binding motif

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

No conflicts of interest exist for any of the authors.

References:

- 1).Loomba R, Sanyal AJ. The global NAFLD epidemic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;10:686–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Younossi Z, Tacke F, Arrese M, Chander Sharma B, Mostafa I, Bugianesi E, et al. Global Perspectives on Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2019;69:2672–2682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Machado MV, Diehl AM. Pathogenesis of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2016;150:1769–1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Gao B, Tsukamoto H. Inflammation in Alcoholic and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Friend or Foe? Gastroenterology 2016;150:1704–1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Schuster S, Cabrera D, Arrese M, Feldstein AE. Triggering and resolution of inflammation in NASH. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;15:349–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Tilg H The role of cytokines in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Dis 2010;28:179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Stojsavljevic S, Gomercic Palcic M, Virovic Jukic L, Smircic Duvnjak L, Duvnjak M. Adipokines and proinflammatory cytokines, the key mediators in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:18070–18091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Moschen AR, Molnar C, Geiger S, Graziadei I, Ebenbichler CF, Weiss H, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of excessive weight loss: potent suppression of adipose interleukin 6 and tumour necrosis factor alpha expression. Gut 2010;59:1259–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Min HK, Mirshahi F, Verdianelli A, Pacana T, Patel V, Park CG, et al. Activation of the GP130-STAT3 axis and its potential implications in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2015;308:G794–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Jorge ASB, Andrade JMO, Paraiso AF, Jorge GCB, Silveira CM, de Souza LR, et al. Body mass index and the visceral adipose tissue expression of IL-6 and TNF-alpha are associated with the morphological severity of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in individuals with class III obesity. Obes Res Clin Pract 2018;12:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Schmidt-Arras D, Rose-John S. IL-6 pathway in the liver: From physiopathology to therapy. J Hepatol 2016;64:1403–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Wieckowska A, Papouchado BG, Li Z, Lopez R, Zein NN, Feldstein AE. Increased hepatic and circulating interleukin-6 levels in human nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:1372–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Miller AM, Wang H, Bertola A, Park O, Horiguchi N, Ki SH, et al. Inflammation-associated interleukin-6/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 activation ameliorates alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver diseases in interleukin-10-deficient mice. Hepatology 2011;54:846–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Mas E, Danjoux M, Garcia V, Carpentier S, Segui B, Levade T. IL-6 deficiency attenuates murine diet-induced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. PLoS One 2009;4:e7929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Hunter CA, Jones SA. IL-6 as a keystone cytokine in health and disease. Nat Immunol 2015;16:448–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Tacke F Targeting hepatic macrophages to treat liver diseases. J Hepatol 2017;66:1300–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).McGettigan B, McMahan R, Orlicky D, Burchill M, Danhorn T, Francis P, et al. Dietary Lipids Differentially Shape Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Progression and the Transcriptome of Kupffer Cells and Infiltrating Macrophages. Hepatology 2019;70:67–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Guillot A, Tacke F. Liver Macrophages: Old Dogmas and New Insights. Hepatol Commun 2019;3:730–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Rose-John S The Soluble Interleukin 6 Receptor: Advanced Therapeutic Options in Inflammation. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2017;102:591–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Fazel Modares N, Polz R, Haghighi F, Lamertz L, Behnke K, Zhuang Y, et al. IL-6 Trans-signaling Controls Liver Regeneration After Partial Hepatectomy. Hepatology 2019;70:2075–2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Baran P, Hansen S, Waetzig GH, Akbarzadeh M, Lamertz L, Huber HJ, et al. The balance of interleukin (IL)-6, IL-6.soluble IL-6 receptor (sIL-6R), and IL-6.sIL-6R.sgp130 complexes allows simultaneous classic and trans-signaling. J Biol Chem 2018;293:6762–6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Wang X, Zheng Z, Caviglia JM, Corey KE, Herfel TM, Cai B, et al. Hepatocyte TAZ/WWTR1 Promotes Inflammation and Fibrosis in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Cell Metab 2016;24:848–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Wang X, Sommerfeld MR, Jahn-Hofmann K, Cai B, Filliol A, Remotti HE, et al. A Therapeutic Silencing RNA Targeting Hepatocyte TAZ Prevents and Reverses Fibrosis in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis in Mice. Hepatol Commun 2019;3:1221–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Wree A, McGeough MD, Inzaugarat ME, Eguchi A, Schuster S, Johnson CD, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome driven liver injury and fibrosis: Roles of IL-17 and TNF in mice. Hepatology 2018;67:736–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Zhang X, Shen J, Man K, Chu ES, Yau TO, Sung JC, et al. CXCL10 plays a key role as an inflammatory mediator and a non-invasive biomarker of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol 2014;61:1365–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26).Mridha AR, Wree A, Robertson AAB, Yeh MM, Johnson CD, Van Rooyen DM, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome blockade reduces liver inflammation and fibrosis in experimental NASH in mice. J Hepatol 2017;66:1037–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27).Tkach M, Thery C. Communication by Extracellular Vesicles: Where We Are and Where We Need to Go. Cell 2016;164:1226–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28).Hirsova P, Ibrahim SH, Verma VK, Morton LA, Shah VH, LaRusso NF, et al. Extracellular vesicles in liver pathobiology: Small particles with big impact. Hepatology 2016;64:2219–2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Garcia-Martinez I, Santoro N, Chen Y, Hoque R, Ouyang X, Caprio S, et al. Hepatocyte mitochondrial DNA drives nonalcoholic steatohepatitis by activation of TLR9. J Clin Invest 2016;126:859–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30).Hirsova P, Ibrahim SH, Krishnan A, Verma VK, Bronk SF, Werneburg NW, et al. Lipid-Induced Signaling Causes Release of Inflammatory Extracellular Vesicles From Hepatocytes. Gastroenterology 2016;150:956–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31).Chen L, Brenner DA, Kisseleva T. Combatting Fibrosis: Exosome-Based Therapies in the Regression of Liver Fibrosis. Hepatol Commun 2019;3:180–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32).Ye D, Zhang T, Lou G, Liu Y. Role of miR-223 in the pathophysiology of liver diseases. Exp Mol Med 2018;50:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33).Guillot A, Tacke F. The Unexpected Role of Neutrophils for Resolving Liver Inflammation by Transmitting MicroRNA-223 to Macrophages. Hepatology 2020;71:749–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34).Calvente CJ, Tameda M, Johnson CD, Del Pilar H, Lin YC, Adronikou N, et al. Neutrophils contribute to spontaneous resolution of liver inflammation and fibrosis via microRNA-223. J Clin Invest 2019;130:4091–4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35).He Y, Hwang S, Cai Y, Kim SJ, Xu M, Yang D, et al. MicroRNA-223 Ameliorates Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis and Cancer by Targeting Multiple Inflammatory and Oncogenic Genes in Hepatocytes. Hepatology 2019;70:1150–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36).Aucher A, Rudnicka D, Davis DM. MicroRNAs transfer from human macrophages to hepato-carcinoma cells and inhibit proliferation. J Immunol 2013;191:6250–6260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37).Ismail N, Wang Y, Dakhlallah D, Moldovan L, Agarwal K, Batte K, et al. Macrophage microvesicles induce macrophage differentiation and miR-223 transfer. Blood 2013;121:984–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38).Zhou Y YF, Li Y, Pan X, Chen Y, Wu X, et al. . Individualized risk prediction of significant fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease using a novel nomogram. United European Gastroenterology Journal 2019;doi: 10.1177/2050640619868352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39).Scott CL, Zheng F, De Baetselier P, Martens L, Saeys Y, De Prijck S, et al. Bone marrow-derived monocytes give rise to self-renewing and fully differentiated Kupffer cells. Nat Commun 2016;7:10321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40).Miura K, Yang L, van Rooijen N, Ohnishi H, Seki E. Hepatic recruitment of macrophages promotes nonalcoholic steatohepatitis through CCR2. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2012;302:G1310–1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41).Li M, He Y, Zhou Z, Ramirez T, Gao Y, Gao Y, et al. MicroRNA-223 ameliorates alcoholic liver injury by inhibiting the IL-6-p47(phox)-oxidative stress pathway in neutrophils. Gut 2017;66:705–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42).Neudecker V, Brodsky KS, Clambey ET, Schmidt EP, Packard TA, Davenport B, et al. Neutrophil transfer of miR-223 to lung epithelial cells dampens acute lung injury in mice. Sci Transl Med 2017;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43).Hessvik NP, Llorente A. Current knowledge on exosome biogenesis and release. Cell Mol Life Sci 2018;75:193–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44).McFarland-Mancini MM, Funk HM, Paluch AM, Zhou M, Giridhar PV, Mercer CA, et al. Differences in wound healing in mice with deficiency of IL-6 versus IL-6 receptor. J Immunol 2010;184:7219–7228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45).Koyama Y, Brenner DA. Liver inflammation and fibrosis. J Clin Invest 2017;127:55–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46).Jimenez Calvente C, Del Pilar H, Tameda M, Johnson CD, Feldstein AE. MicroRNA 223 3p Negatively Regulates the NLRP3 Inflammasome in Acute and Chronic Liver Injury. Mol Ther 2020;28:653–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47).Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J Cell Biol 2013;200:373–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.