Abstract

Introduction

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic resulted in major disruption to hip fracture services. This frail patient group requires specialist care, and disruption to services is likely to result in increases in morbidity, mortality and long-term healthcare costs.

Aims

To assess disruption to hip fracture services during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

A questionnaire was designed for completion by a senior clinician or service manager in each participating unit between April–September 2020. The survey was incorporated into existing national-level audits in Germany (n = 71), Scotland (n = 16), and Ireland (n = 16). Responses from a further 82 units in 11 nations were obtained via an online survey.

Results

There were 185 units from 14 countries that returned the survey. 102/160 (63.7%) units reported a worsening of overall service quality, which was attributed predominantly to staff redistribution, reallocation of inpatient areas, and reduced access to surgical facilities. There was a high rate of redeployment of staff to other services: two thirds lost specialist orthopaedic nurses, a third lost orthogeriatrics services, and a quarter lost physiotherapists. Reallocation of inpatient areas resulted in patients being managed by non-specialised teams in generic wards, which increased transit of patients and staff between clinical areas. There was reduced operating department access, with 74/160 (46.2%) centres reporting a >50% reduction. Reduced theatre efficiency was reported by 135/160 (84.4%) and was attributed to staff and resource redistribution, longer anaesthetic and transfer times, and delays for preoperative COVID-19 testing and using personal protective equipment (PPE).

Conclusion

Hip fracture services were disrupted during the COVID-19 pandemic and this may have a sustained impact on health and social care. Protection of hip fracture services is essential to ensure satisfactory outcomes for this vulnerable patient group.

Keywords: Hip, Neck of femur, Fracture, COVID-19, IMPACT, Services, Survey, Mortality, Disruption, Redeployment, Orthogeriatrics, Frailty, Fragility

Introduction

The annual incidence of hip fracture is 75,000/year in the UK, where inpatient hospital costs are £1.1 billion/year, and the delivery of care is complex. The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic resulted in major disruption to hip fracture care processes.1 This frail patient group requires specialist care, and disruption to services is likely to result in increases in morbidity, mortality and long-term health and social care costs.2

Although there was a reduction in activity-related trauma during the COVID-19 pandemic, the incidence of fragility trauma was observed to increase or remained unchanged.3, 4, 5 Hospital services were reconfigured to meet the challenges of the pandemic, and the need to accommodate segregated inpatient areas, increase critical care capacity, and establish wards for COVID-19 patients all caused disruption to hip fracture services.6 , 7

This study reports findings of the International Multicentre Project Auditing COVID-19 in Trauma & Orthopaedics (IMPACT) Services Survey, which assessed disruption to hip fracture services in 185 centres across 14 nations and considers the possible unseen effects on this vulnerable patient group.

Methods

IMPACT is an emergency collaborative network that was established in March 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, with support from the Scottish Hip Fracture Audit (SHFA), Scottish Committee for Orthopaedics & Trauma (SCOT), and Scottish Government.8 IMPACT Services Survey was developed to investigate the effects of the pandemic on hip fractures services.

A questionnaire was designed for completion by a senior clinician or service manager in each participating unit between April–September 2020. Unit participation was facilitated by incorporation into existing national-level audits in Germany (n = 71), Scotland (n = 16), and Ireland (n = 16). Responses from a further 82 units were obtained via online survey (Survey Monkey, San Mateo, USA) from: UK (England, Wales, and Northern Ireland) (n = 40); Spain (n = 28); Italy (n = 4); New Zealand (n = 4); Sudan (n = 2); Mexico (n = 1); China (n = 1); Colombia (n = 1), and India (n = 1).

Quantitative data

Unit characteristics collected were: hospital trauma level, baseline hip fracture volume, change in hip fracture volume, and estimated COVID-19 prevalence. Measures of service change included redeployment rate (by staff group), access to theatre (percentage of normal), theatre efficiency (percentage of normal), and overall trauma service quality (‘improved’, ‘worsened’, or ‘unchanged’).

Qualitative data

Data were collected regarding staff and resource redistribution, patient-level management, effect of suspected/confirmed COVID-19 status on management, and overall effects of COVID-19 on hip fracture services.

Results

There were 185 units from 14 countries that returned the survey. Of these 45/185 (24.3%) were Level I Trauma Centres (equivalent to UK Major Trauma Centre),9 134/185 (72.4%) Level II or III Trauma Centres (UK Trauma Unit), and 6/185 (3.2%) hospitals that usually provide elective orthopaedic services (prior to the pandemic).

There were 91/173 (52.6%) units that reported an unchanged volume of hip fracture admissions, 74/173 (42.8%) that reported a reduction, and 8/173 (4.6%) an increased volume. Units that reported a reduction in volume completed the survey earlier in the study period, which coincided with the initial social lockdown measures.

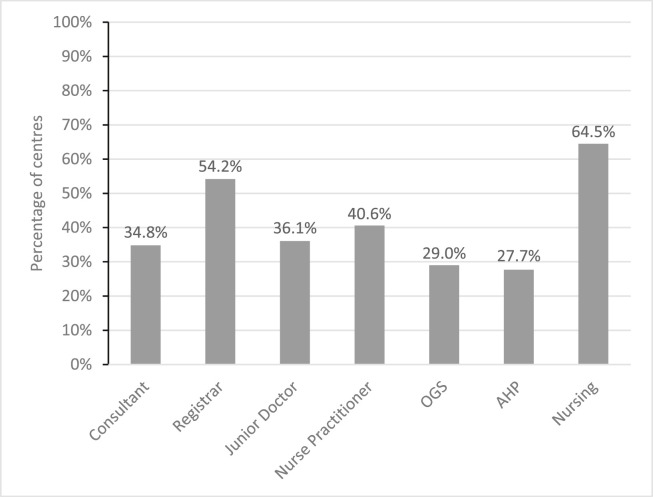

There were 102/160 (63.7%) units that reported a worsening of overall service quality, which was attributed predominantly to staff redistribution, reallocation of inpatient areas, and reduced access to surgical facilities. There was a high rate of redeployment of staff to other services: two-thirds lost specialist orthopaedic nurses, a third lost orthogeriatrics services, and a quarter lost physiotherapists (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Percentage of redeployment according to staff grade and discipline reported during the study period.

Reallocation of inpatient areas resulted in patients being managed by non-specialised teams in generic wards, which increased the transit of patients and staff between clinical areas. Some units reported the transfer of patients to separate ‘cold’ hospital sites for definitive orthopaedic management.

There was reduced operating department access, with 74/160 (46.2%) centres reporting a >50% reduction. Reduced theatre efficiency was reported by 135/160 (84.4%) and was attributed to staff and resource redistribution, longer anaesthetic and transfer times, and delays for preoperative COVID-19 testing and using personal protective equipment (PPE).

Discussion

Almost two-thirds (64%) of units who returned the survey reported a reduced overall quality of service during the study period. This was attributed predominantly to the redeployment of members of the hip fracture multidisciplinary team (MDT), a redistribution of inpatients areas, and a reduction in operating theatre access and efficiency.

High-quality hip fracture care delivered by an MDT according to evidence-based guidelines is associated with improved outcomes including length of hospital stay, post-discharge level of care, and mortality.10, 11, 12 Redeployment of specialist staff and the consequent disruption to acute services may result in poorer survival and functional outcome, increased care demands, and an increased burden on health and social care services.

Patients with hip fractures are particularly vulnerable to acquiring COVID-19 and the prevalence in this group has been reported to be 13%,13 many times greater than the general population. A positive COVID-19 status is independently associated with a three-times increased mortality risk in hip fracture patients, and hospital-acquired infection may account for a half of all COVID-19 cases within 30 days of admission.1 , 13, 14, 15 The survey found variation in the strategies for the management of patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19, which highlights the need for the development and continuous refinement of evidence-based methods to reduce in-hospital transmission, such as the use of patient pathways or ‘circuits’ to ensure the effective isolation or shielding of patients identified as being at risk of transmitting or acquiring the disease.15 , 16 Furthermore the retention of inpatient orthopaedic areas is required to reduce the movement of patients and staff between multiple clinical areas, which is known to be associated with increased psychological stress, delirium, increased length of stay, and mortality, and has been shown to be an effective strategy in the reduction of hospital-acquired COVID-19.17 , 18

The survey reported reduced operating department access and efficiency which resulted in delays to surgical management. Prolonged time to surgery is associated with higher complication rates, length of stay, and mortality in hip fracture, and safe early surgery remains the strategy of choice in the context of COVID-19.19, 20, 21

Conclusion

Hip fracture services have suffered disruption during the COVID-19 pandemic that may have a sustained impact on health and social care. Protection of hip fracture services is essential to ensure satisfactory outcomes for this vulnerable patient group.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Karen Adam (Scottish Government) who made rapid collaboration possible, and the important contributions of all participants of the International Multicentre Project Auditing COVID-19 in Trauma & Orthopaedics (IMPACT) Collaborative.

References

- 1.Clement N.D., Hall A.J., Makaram N.S., Robinson P.G., Patton R.F.L., Moran M., et al. IMPACT-Restart: the influence of COVID-19 on postoperative mortality and risk factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection after orthopaedic and trauma surgery. Bone Joint J. 2020;102-B(12):1774–1781. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.102B12.BJJ-2020-1395.R2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farrow L., Hall A., Wood A.D., Smith R., James K., Holt G., et al. Quality of care in Hip fracture patients: the relationship between adherence to national standards and improved outcomes. J Bone Jt Surg - Am. 2018 May;100(9):751–757. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.00884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jenkins P.J. BOA; 2020. The early effect of COVID-19 on trauma and elective orthopaedic surgery. British Orthopaedic Association (BOA)https://www.boa.ac.uk/policy-engagement/journal-of-trauma-orthopaedics/journal-of-trauma-orthopaedics-and-coronavirus/the-early-effect-of-covid-19-on-trauma-and-elect.html [Internet] Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott C.E., Holland G., Powell-Bowns M.F., Brennan C.M., Gillespie M., Mackenzie S.P., et al. Population mobility and adult orthopaedic trauma services during the COVID-19 pandemic: fragility fracture provision remains a priority. Bone Jt Open. 2020;1(6) doi: 10.1302/2633-1462.16.BJO-2020-0043.R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luceri F., Morelli I., Accetta R., Mangiavini L., Maffulli N., Peretti G.M. Italy and COVID-19: the changing patient flow in an orthopedic trauma center emergency department. J Orthop Surg Res. 2020;15(1):323. doi: 10.1186/s13018-020-01816-1. [Internet] Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wright E.V., Musbahi O., Singh A., Somashekar N., Huber C.P., Wiik A.V. Increased perioperative mortality for femoral neck fractures in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): experience from the United Kingdom during the first wave of the pandemic. Patient Saf Surg. 2021;15(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s13037-020-00279-x. [Internet] Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flemming S., Hankir M., Ernestus R.-I., Seyfried F., Germer C.-T., Meybohm P., et al. Surgery in times of COVID-19—recommendations for hospital and patient management. Langenbeck’s Arch Surg. 2020;405(3):359–364. doi: 10.1007/s00423-020-01888-x. [Internet] Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall A.J. 2020. IMPACT: international Multicentre Project auditing COVID-19 in trauma & orthopaedics.https://www.trauma.co.uk/impact [Internet] Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen J. 2018. What is the difference between A level 1, level 2, and level 3 trauma center?https://hospitalmedicaldirector.com/what-is-the-difference-between-a-level-1-level-2-and-level-3-trauma-center/ [Internet] [cited 2021 Mar 5]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farrow L., Hall A., Aucott L., Holt G., Myint P.K. Does quality of care in hip fracture vary by day of admission? Arch Osteoporos. 2020 Mar 20;15(1) doi: 10.1007/s11657-020-00725-4. https://europepmc.org/articles/PMC7083802 [Internet] Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Metcalfe D., Zogg C.K., Judge A., Perry D.C., Gabbe B., Willett K., et al. Pay for performance and hip fracture outcomes: an interrupted time series and difference-in-differences analysis in England and Scotland. Bone Jt J. 2019 Aug 17;101 B(8):1015–1023. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.101B8.BJJ-2019-0173.R1. https://online.boneandjoint.org.uk/doi/suppl/10.1302/0301-620X.101B8.BJJ-2019-0173.R1/suppl_file/Farrow/etal/eLetter/reBJJ-2019-0173.R1.ed.pdf [Internet] Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel J.N., Klein D.S., Sreekumar S., Liporace F.A., Yoon R.S. Outcomes in multidisciplinary team-based approach in geriatric hip fracture care: a systematic review. JAAOS - J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28(3) doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-18-00425. https://journals.lww.com/jaaos/Fulltext/2020/02010/Outcomes_in_Multidisciplinary_Team_based_Approach.9.aspx [Internet] Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clement N.D., Ng N., Simpson C.J., Patton R.F.L., Hall A.J., Simpson A.H.R.W., et al. The prevalence, mortality, and associated risk factors for developing COVID-19 in hip fracture patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bone Jt Res. 2020;9(12):873–883. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.912.BJR-2020-0473.R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall A.J., Clement N.D., Farrow L., MacLullich A.M.J., Dall G.F., Scott C.E.H., et al. IMPACT-Scot report on COVID-19 and hip fractures: a multicentre study assessing mortality, predictors of early SARS-CoV-2 infection, and the effects of social lockdown on epidemiology. Bone Jt J. 2020;102-B(9):1219–1228. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.102B9.BJJ-2020-1100.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall A.J., Clement N.D., MacLullich A.M.J., White T.O., Duckworth A.D. IMPACT-Scot 2 report on COVID-19 in hip fracture patients. Bone Joint J. 2021:1–10. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.103B.BJJ-2020-2027.R1. [Internet] 0(0):Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ojeda-Thies C., Cuarental-García J., García-Gómez E., Salazar-Zamorano C.H., Alberti-Maroño J., Ramos Pascua L.R. Hip fracture care and mortality among patients treated in dedicated COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 circuits. Eur Geriatr Med. 2021:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s41999-021-00455-x. [epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McMurdo M.E.T., Witham M.D. Unnecessary ward moves. Age Ageing. 2013 Sep 1;42(5):555–556. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft079. [Internet] Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeng H., Li G., Weng J., Xiong A., Xu C., Yang Y., et al. The strategies of perioperative management in orthopedic department during the pandemic of COVID-19. J Orthop Surg Res. 2020;15(1):474. doi: 10.1186/s13018-020-01978-y. [Internet] Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klestil T., Röder C., Stotter C., Winkler B., Nehrer S., Lutz M., et al. Impact of timing of surgery in elderly hip fracture patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):13933. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-32098-7. [Internet] Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muñoz Vives J., Jornet-Gibert M., Cámara-Cabrera J., Esteban P., Brunet L., Delgado-Flores L., et al. Mortality rates of patients with proximal femoral fracture in a worldwide pandemic: preliminary results of the Spanish HIP-COVID Observational study. J bone Jt Surg. 2020;102(13):69. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.20.00686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morelli I., Luceri F., Giorgino R., Accetta R., Perazzo P., Mangiavini L., et al. COVID-19: not a contraindication for surgery in patients with proximal femur fragility fractures. J Orthop Surg Res. 2020;15(1):285. doi: 10.1186/s13018-020-01800-9. [Internet] Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]