Introduction

Rupioid skin lesions usually develop on a background of immunosuppression and are grossly hyperkeratotic cone-shaped plaques with thick, dark, adherent, and lamellate crusts resembling limpet shells.1 Relatively few etiologies, mainly infectious, are relevant to the differential diagnosis of rupioid presentations, including syphilis, HIV, scabies, histoplasmosis, rupioid psoriasis (RupP), or reactive arthritis.1

RupP is an uncommon condition resulting from a pronounced inflammatory response, leading to abnormal keratinized scale mixing with copious sero-exudate.2 The lesions exhibit classic histopathologic findings of psoriasis.1 Drug-provoked psoriasis (either drug-aggravated or drug-induced) is similarly infrequent, with lithium, beta-blockers, and antimalarials being the most common causative agents.3 Drug-induced RupP is extremely rare, with only a few reports in the literature (Table I).

Table I.

Summary of drug-provoked rupioid psoriasis (RupP) cases identified in PubMed

| Study | Drug | Age (years)/Sex | Refractory period (months)† | R/O∗ | Location | Other presenting symptoms | Psoriasis history | Type | Drug d/c | Treatment | Time to resolution (weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nascimento et al13 | Carbolithium | 38/M | 10 | O | Diss | Pain, pruritis | No | DNI | Yes | MTX (15 mg/week), urea (10%) emollient | 4 |

| Marti-Marti et al14 | Pembrolizumab | 67/M | 1.5 | R | Diss | Nail dystrophy, palmoplantar keratoderma | Yes | INLS | Yes | Acitretin (25 mg/day), SA (10%), triamcinolone acetonide (0.1%) |

NS |

| Gomez-Arias et al15 | Valproic acid | 42/M | 2.5 | R | Dorsal hands | NS | Yes | Agg | No | MTX (15 mg/week) | 8 |

| Bonciani et al16 | Prednisone | 54/F | NS | R | Diss | Fever, chills, rigors | Yes | Agg | NS | Acitretin (30 mg/day), urea (20%) ointment |

3 |

| Current case | Treprostinil, macitentan, tadalafil | 69/F | 12 | R | Diss | None | No | DNI | No | See above | 8 |

Agg, Aggravation of pre-existing lesion; d/c, discontinued; Diss, disseminated; DNI, de-novo induction; F, female; INLS, induction of non-lesional skin in patient with psoriasis history; M, male; MTX, methotrexate; NS, not specified; O, ostraceous; R, rupioid; SA, salicylic acid.

Some authors consider RupP and ostraceous psoriasis synonyms and use the terms interchangeably to describe the same hyperkeratotic psoriasis variant.13

Time to RupP onset since drug initiation.

Herein, we present a case of a patient who developed de-novo disseminated RupP 12 months after initiating a strong vasodilatory drug regimen for pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) and hypothesize on the possible pathogenic mechanisms underlying this unusual presentation.

Case report

A 69-year-old woman presented with a 3-month history of disseminated dark, confluent, squamous plaques with overlying, thick, sero-exudative crusts affecting trunk, extremities, flexures, genitalia, groin, and plantar feet. (Fig 1, A). She was diagnosed with PAH and placed on a strong vasodilatory regimen (treprostinil, macitentan, tadalafil) 12 months prior (therapeutic levels achieved 6 months previously) to lesion onset. There was no personal or family history for psoriasis. She denied any joint pain, stiffness, or other systemic symptoms. A close-up view of the lesions demonstrated prominent circular concentric layers of scale (Fig 1, B). Nails, scalp, face, palms, and mucosae were uninvolved. Laboratory testing was unremarkable, including nonreactive syphilis and HIV serologies. Biopsy findings were consistent with psoriasis, revealing hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, papillomatosis, and dilated dermal papillae with perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and exocytosis of neutrophils in the stratum corneum (Fig 2).

Fig 1.

Clinically representative images of presenting rupioid psoriasis lesions. A, Rupioid lesions on the anterior aspects of the lower extremities. B, Close-up view demonstrating well-demarcated plaques with conical circular concentric layers of adherent scale consistent with rupioid lesions.

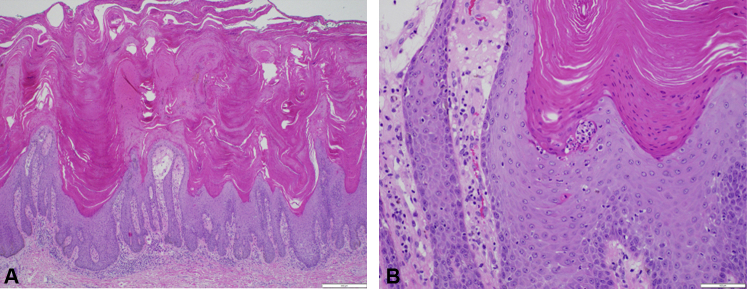

Fig 2.

Skin biopsy of representative lesion from right thigh. A, Papillomatous epidermal hyperplasia with compact hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, hypogranulosis, and suprapapillary thinning with dilated dermal vessels and perivascular infiltrate composed of neutrophils and lymphocytes. B, Neutrophils present in the stratum corneum. (A and B, Hematoxylin-eosin stain; original magnifications: A, ×4; B, ×20.)

Cardiopulmonary consultation advised against modifying her PAH medications. The patient was started on weekly methotrexate of 15 mg, with 1 mg daily of folic acid supplementation as well as topical therapy of calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate (0.064%/0.005%) foam. Within two months, the patient had significant improvement in her skin lesions (Fig 3). Methotrexate was subsequently tapered for 1 month. She remains asymptomatic 3 months post-treatment.

Fig 3.

Full clinical resolution upon completion of a 2-month course of methotrexate. Mild post-inflammatory hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation were observed.

Discussion

RupP indicates extensive cutaneous inflammation and may be suggestive of immunosuppression, such as HIV infection.1 We describe the possible associations between our patient's new-onset RupP presentation and vasodilatory regimen consisting of an endothelin A and B receptor antagonist (macitentan), a prostacyclin analog (treprostinil), and a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor (tadalafil).

A laser Doppler investigation of blood vessels in psoriatic plaques found greater basal blood flow and significantly greater maximum flux after vasodilatory provocation relative to non-involved skin.4 These findings are likely a result of increased quantity, width, and length of superficial vessels, but may also be due to plaque-associated vascular abnormalities in deeper dermal arterioles.4,5 The vasodilatory effects resulting from the simultaneous intake of the aforementioned drugs conceivably contributed toward our patient's rupioid eruption. However, other medication-related mechanisms could also have played significant roles in disease precipitation, as described per each agent below.

Tadalafil exerts its potent vasodilatory effects by increasing cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) levels. Epidermal hyperplasia in psoriatic lesions is postulated to be associated with increased lesional cGMP levels6 and a decreased cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)/cGMP ratio, explaining the aggravation of psoriasis with common beta-blocking agents.7 Indeed, cAMP and cGMP have opposing effects on epidermal proliferation, with the latter likely being stimulatory.7

Treprostinil acts on the prostanoid receptor EP2,8 the downstream effects of which on lymphocytes enhance pathogenic Th17-mediated immune responses known to play critical roles in psoriasis pathogenesis and inflammation.9 Interestingly, treprostinil's vasodilatory effects are cAMP-mediated,8 implying possible anti-proliferative effects at the keratinocyte level through prostacyclin receptor activation. Therefore, if treprostinil played a role in our patient's eruption it could be a complex interaction of pro-psoriatic immunopathogenic and nonspecific vasodilatory effects outweighing the aforementioned cAMP-protective anti-psoriatic activity.

Lastly, macitentan, a mixed endothelin receptor antagonist with greater selectivity for endothelin A (ETA) than endothelin B (ETB) receptors,10 would be expected to have anti-psoriatic properties through antagonism of both the endothelin-1-mediated keratinocyte proliferation11 and pro-psoriatic inflammatory cascade stimulation.12 Psoriatic lesions have increased expression of endothelin 1, and topical application of a selective ETA receptor antagonist (ambrisentan) attenuates imiquimod-induced psoriasiform inflammation development.12 The strong vasodilating properties of systemic macitentan could have overcome its anti-proliferative and anti-inflammatory effects, as demonstrated during in-vitro experimentation. Interestingly, selective ETB receptor antagonism produces no therapeutic effect on imiquimod-induced psoriasiform dermatitis.12 Also, unlike ETA receptor blockade, ETB receptor antagonism enhances dendritic cell mediated immune responses.12 The differential degree of endothelin receptor inhibition by macitentan may produce complex interactions in various tissues resulting in psoriasis induction.

The refractory period for drug-provoked psoriasis is variable, ranging from weeks to over a year.3 Reported drug-provoked RupP cases implicate pharmacologically unrelated drugs, suggesting that there are multiple molecular pathogenic mechanisms leading to development of rupioid lesions (Table I). While inflammation can be potentiated by lithium-mediated modulation of adenylyl cyclase and inositol monophosphatase pathways13 and immune check-point inhibition with pembrolizumab,14 our patient's presentation was more complex. We hypothesize that the immunopathogenic, hyperproliferative, and vasodilatory properties of our patient's recently initiated PAH drug regimen synergistically contributed toward her presentation.

Importantly, our claims are speculative. Assessing the relationship between the RupP eruption and drug regimen modifications was not possible. Nonetheless, discontinuation of culprit drugs inconsistently leads to drug-provoked psoriasis resolution.3 Further, it is necessary to underscore that it is similarly likely that the patient's RupP eruption was idiopathic, possibly triggered by the underlying inflammatory state of PAH or stress. Considering our patient's immunocompetent status, late-age acute RupP onset, lack of consumption of other medications associated with drug-provoked psoriasis, and negative family and personal history of psoriasis, we speculate that her recently initiated vasodilatory regimen played a significant role in the pathogenesis.

In conclusion, we present a case of RupP possibly associated with vasodilatory PAH medications. With rupioid lesions it is necessary to rule out infectious etiologies such as syphilis and HIV, especially in settings of systemic immunosuppression. Hence, we emphasize the importance of taking a thorough drug history in patients with rupioid lesions.

Conflicts of interest

None disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our appreciation to the patient for providing consent for the publication of this case.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

IRB approval status: Not applicable.

References

- 1.Steele C.E., Anderson M., Miedema J., Culton J. Rupioid psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in a patient with skin of color. Cutis. 2020;106(1):E2–E4. doi: 10.12788/cutis.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang J.L., Yang J.H. Rupioid psoriasis associated with arthropathy. J Dermatol. 1997;24(1):46–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1997.tb02738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim G.K., Del Rosso J.Q. Drug-provoked psoriasis: is it drug induced or drug aggravated?: understanding pathophysiology and clinical relevance. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3(1):32–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hern S., Stanton A.W., Mellor R., Levick J.R., Mortimer P.S. Control of cutaneous blood vessels in psoriatic plaques. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113(1):127–132. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hern S., Stanton A.W.B., Mellor R.H., Harland C.C., Levick J.R., Mortimer P.S. Blood flow in psoriatic plaques before and after selective treatment of the superficial capillaries. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152(1):60–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cantieri J.S., Graff G., Goldberg N.D. Cyclic GMP metabolism in psoriasis: increased activity of soluble epidermal cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase and its modulation by calcium. Br J Dermatol. 1981;104(3):301–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1981.tb00953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raab W.P. Cyclic nucleotides and prostaglandins in psoriasis. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 1980;18(5):212–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pedersen M.L., Krüger M., Grimm D., Infanger M., Wehland M. The prostacyclin analogue treprostinil in the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2019 doi: 10.1111/bcpt.13305. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee J., Aoki T., Thumkeo D., Siriwach R., Yao C., Narumiya S. T cell-intrinsic prostaglandin E2-EP2/EP4 signaling is critical in pathogenic TH17 cell-driven inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(2):631–643. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Correale M., Ferraretti A., Monaco I., Grazioli D., Biase M.D., Brunetti N.D. Endothelin-receptor antagonists in the management of pulmonary arterial hypertension: where do we stand? Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2018;14:253–264. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S133921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simeone P., Teson M., Latini A., Carducci M., Venuti A. Endothelin-1 could be one of the targets of psoriasis therapy. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151(6):1273–1275. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakahara T., Kido-Nakahara M., Ulzii D. Topical application of endothelin receptor a antagonist attenuates imiquimod-induced psoriasiform skin inflammation. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):9510. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66490-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.do Nascimento B.A.M., Carvalho A.H., Dias C.M., Lage T.L., Carneiro C.M.O., Bittencourt M.D.J.S. A case of generalized ostraceous psoriasis mimicking dermatitis neglecta. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(3 Suppl 1):197–199. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marti-Marti I., Gómez S., Riera-Monroig J., Carrera C., Mascaró J.M. Rupioid psoriasis induced by pembrolizumab. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86(5):580–582. doi: 10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_1067_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gómez-Arias P.J., García-Nieto A.J.V. Rupioid psoriasis on the hands. CMAJ. 2020;192(45):E1407. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.200517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonciani D., Bonciolini V., Antiga E., Verdelli A., Caproni M., Senetta R. A case of rupioid psoriasis exacerbated by systemic glucocorticosteroids. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54(4):e100–e102. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]