The COVID-19 pandemic has largely and rightly focussed on the acute needs of the population, however; as infection rates continue to fall the need for rehabilitation services continue to rise. Initially it was expected that people hospitalised with COVID-19, particularly those treated in intensive care and high dependency units would require rehabilitation to return to their usual activities but it has become clear that there is a demand for rehabilitation for those hospitalised and non-hospitalised-following infection [1], [2].

There have been a number of studies that have identified that symptoms of breathlessness, fatigue, generalised joint pain and reduced cognition persist long after the initial infection and can prevent return to work and reduced engagement in activities of daily living [3], [4]. Those experiencing symptoms 12 weeks after their initial infection, termed long COVID or long haulers, are in need of support and interventions to assist their recovery [5]. A number of specialist groups and governing bodies have identified the need for rehabilitation, and have suggested adaptive pulmonary rehabilitation services would be best place to meet the demands of the long COVID population [2], [6], [7]. However, current pulmonary rehabilitation services are overstretched with high demand from the chronic respiratory disease population. Therefore there is a need to enhance capacity of such rehabilitation services to support the needs of the post COVID population.

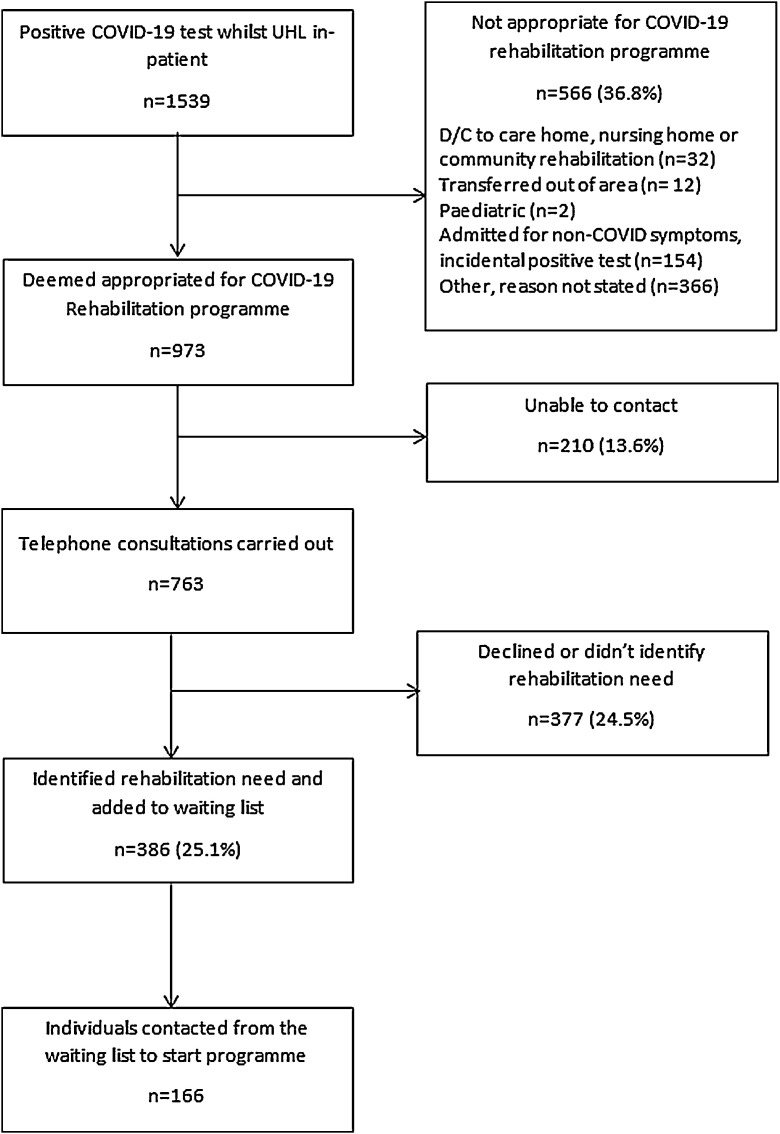

People discharged from the University of Leicester between March and December 2020 were followed up on a rehabilitation pathway, which included a phone call to identify any ongoing symptoms and rehabilitation needs. All individuals with a positive COVID-19 PCR test, or clinical diagnosis of COVID-19 were screened. One thousand five hundred thirty nine individuals were screened, of these, 566 (37%) were deemed not appropriate for an outpatient rehabilitation programme (reasons outlined in Fig. 1 ). Seven hundred sixty three individuals completed a telephone consultation, the mean [SD] age was 60 [16] years and average time from discharge to telephone consultation was 42 [22] days. Three hundred eighty six individuals identified rehabilitation needs (25% of all screened) and were added to a waiting list. One hundred sixty six individuals added to the waiting list had been contacted by end of January 2021 and offered the rehabilitation programme. The average length of time from hospital discharge to offer of rehabilitation was a mean [SD] of 192 days [72]. One hundred nine individuals (66%) accepted an appointment. Fifty seven individuals (34%) declined an assessment most commonly because their condition had improved (n = 22, 13%) or because they could not be contacted (n = 16, 10%). This data shows 25% of all individuals hospitalised with a positive test or clinical diagnosis of COVID-19 identified rehabilitation needs. This data suggests natural recovery with 24% declining rehabilitation at telephone consultation and a further four percent declining when offered an assessment for a COVID-19 rehabilitation programme.

Fig. 1.

Consort diagram of individuals discharged from UHL hospitals (April–December 2020) offered a telephone consultation for COVID-19 rehabilitation programme. % given is of all participants screened (n = 1539).

Current rehabilitation services could expect volumes of up to 25% of all those hospitalised with a positive COVID-19 swab. This places a huge demand on pre-exisitng services, or the development of new services. There may be a greater uptake of rehabilitation as waiting list time reduces, however, those identifying rehabilitation needs may reduce as acute treatment becomes more effective. The impact of lockdown easing and returning to usual activities may assist recovery, or on the contrary, identify areas in which individuals are struggling to manage their symptoms.

Recent data reports that 71% of hospitalised patients are not fully recovered at 5 months [4] suggesting an even more significant demand for rehabilitation services. However, we found 25% of hospitalised patients experience on-going symptoms that require support for recovery. The reasons for the disparity in the data may be twofold. Firstly, this data reports on everyone discharged from the hospital and provides a real world insight into those who are fully recovered that may not be captured by a research trial. Secondly, there may be ongoing symptoms in those who declined rehabilitation that are not addressed during a conventional rehabilitation programme addressing the previously highlighted symptoms and require different support, which may be captured in the PHOSP data e.g. taste/smell. That said; it is estimated that 1.1 million people in the UK are living with long COVID symptoms, many of which will not have been hospitalised and therefore not captured in these dataset and the requirements for recovery programmes are paramount [8].

COVID rehabilitation services have shown the potential of improving symptoms of long COVID however the ability for services to maintain this delivery will be difficult when usual services resume [9], [10]. Current services have modified or ceased their intervention during the pandemic due to shielding, lockdown restrictions and staff redeployment. Once routine services recommence there is likely to be a backlog of patients requiring conventional rehabilitation services, which will be exacerbated by the demand for COVID-19 rehabilitation services. Capacity of rehabilitation programme classes will be limited by social distancing and infection prevention measures. This will require services to be flexible in its delivery of programmes, and an option for face to face and digital interventions may help meet the demand of these people. It is important to consider the uncertainty surrounding the long term sequela expected in COVID-19 and services may need to rapidly adapt to keep up with the challenges of symptoms, and lockdown measures. Some patients may require minimal advice and support, rather than a comprehensive programme to return to usual activities, and therefore, lighter touch interventions or online resources could be beneficial such as Your COVID Recovery (www.yourcovidrecovery.nhs.uk) [7].

The need for COVID-19 rehabilitation programmes is clear, with 25% of all individuals admitted to our hospitals identifying rehabilitation needs. This presents a significant challenge for services providing rehabilitation which will continue after the pressure on acute services has eased. In order to meet the needs of those with long COVID there needs to be nationwide support for the development and implementation of COVID recovery programmes.

Ethical approval: None required. Funding: There is no funding to declare. This study is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Daynes E., Gerlis C., Briggs-Price S., Jones P., Singh S. COPD assessment test for the evaulation of COVID-19 symptoms. Thorax. 2021;76:185–187. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spruit M.A., Holland A.E., Singh S.J., Tonia T., Wilson K.C., Troosters T. COVID-19: interim guidance on rehabilitation in the hospital and post-hospital phase from a European Respiratory Society and American Thoracic Society-coordinated International Task Force. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(6):2002197. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02197-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saloner B., Parish K., Ward J., DiLaira G., Dolovich S. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. Am Med Assoc. 2020;324(6):603–605. [Google Scholar]

- 4.PHOSP-COVID Collaborative Group, Evans R., McAuley H. Physical, cognitive and mental health impacts of COVID-19 following hospitilisation—a multi-centre prospective cohort study. MedRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00383-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institute for Clinical Excellence. COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long term effects of COVID-19 2020. Available from www.nice.org.uk [NG188] [Accessed 26 April 2021]. [PubMed]

- 6.British Thoracic Society. Delivering rehabilitation to patients surviving COVID-19 using an adapted pulmonary rehbailitation approach- BTS guidance 2020. Available from www.brit-thoracic.org.uk [Accessed 26 April 2021].

- 7.NHS England Your COVID Recovery document 2020. https://smex12-5-en-ctp.trendmicro.com:443/wis/clicktime/v1/query?url=https%3a%2f%2fwww.england.nhs.uk%2fcoronavirus%2fwp%2dcontent%2fuploads%2fsites%2f52%2f2020%2f11%2fYour%2dCOVID%2dRecovery%2dguidance191120.pdf&umid=a01d1dbd-9420-42f8-9fe7-a2bb485d4fdb&auth=4b3e8984ae6d49f00c0caccd5db3f99bac9850df-af7c7fc93e994a141347e3988ab68f9800c54e31 [Accessed April 2021].

- 8.Office of National Statistics. Prevelance of ongoing symptoms following coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in the UK: 1 April 2021. Available from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/prevalenceofongoingsymptomsfollowingcoronaviruscovid19infectionintheuk/1april2021 [Accessed 26 April 2021].

- 9.Daynes E., Gerlis C., Chaplin E., Gardinder N., Singh S. Early experiences of rehabilitations for patients post-COVID to improve fatigue, breathlessness, exercise capacity and cognition. CRD. 2021;18(1):1–4. doi: 10.1177/14799731211015691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodwin V., Allan L., Bethel A., Morley N., Coon J., Lamb S. Rehabilitation to enable recovery from COVID-19: a rapid systematic review. Physiotherapy. 2021;111(1):4–22. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2021.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]