Abstract

In 1997 the Direction del la santé publique de Montréal-Centre initiated “Physicians Taking Action Against Smoking,” a 5-year intervention program to improve the smoking cessation counselling practices of general practitioners (GPs) in Montreal. Program development was guided by the precede-proceed model. This model advocates identifying factors influencing the outcome, in this case counselling practices. These factors are then used to determine the program objectives, to develop and tailor program activities and to design the evaluation. Program activities during the first 3 years included cessation counselling workshops and conferences for GPs, publication of articles in professional interest journals, publication of clinical guidelines for smoking cessation counselling and dissemination of educational material for both GPs and smokers. The program also supported activities encouraging smokers to ask their GPs to help them stop smoking. Results from 2 cross-sectional surveys, conducted in 1998 and 2000, of random samples of approximately 300 GPs suggest some improvements over time in several counselling practices, including offering counselling to more patients and discussing setting a quit date. More improvements were observed among female than male GPs in both psychosocial factors related to counselling and specific counselling practices. For example, improvements were noted among female GPs in self-perceived ability to provide effective counselling and in the belief that it is important to schedule specific appointments to help patients quit; in addition, the perceived importance of several barriers to counselling decreased among female GPs. A greater proportion of the female respondents to the 2000 survey offered written educational material than was the case in 1998, and a greater proportion of the male GPs devoted more time to counselling in 2000 than in 1998; however, among male GPs the proportion who discussed the pros and cons of smoking with patients in the precontemplation stage declined between 1998 and 2000, as did the proportion who referred patients in the preparation stage to community resources. Our experience suggests that an integrated, theory-based program to improve physicians' counselling practices could be a key component of a comprehensive strategy to reduce tobacco use.

The health benefits of smoking cessation are well established,1 and physicians are acknowledged as the health care providers of choice for provision of cessation counselling.2 Over the past decade several training programs have been developed in Canada to improve counselling practices among physicians, including the BC Doctors' Stop-Smoking Program,3 introduced in May 1990 by the British Columbia Medical Association; the Guide Your Patients to a Smoke-Free Future program,4 initiated in August 1992 by the Canadian Council on Smoking and Health and the College of Family Physicians of Canada;5 and the Mobilizing Physicians for Clinical Tobacco Intervention, developed by the Canadian Medical Association, Physicians for a Smoke-Free Canada, the BC Doctors' Stop-Smoking Program, and the medical associations of Ontario and Prince Edward Island.6

Physicians Taking Action Against Smoking is a 5-year program, initiated in 1997 by the Direction de la santé publique de Montréal-Centre, to improve cessation counselling practices among general practitioners (GPs) in Montreal. In addition to having features common to previous initiatives, the Montreal program is based on behaviour change models and therefore incorporates objectives to improve psychosocial precursors to behaviour change, including beliefs, attitudes and self-perceived ability to provide effective counselling. The program was developed as an integral component of a comprehensive province-wide initiative for smoking prevention, protection and cessation,7 which calls for health care professionals, physicians in particular, to deliver smoking cessation interventions.

This paper describes the theoretical model underlying the Physicians Taking Action Against Smoking program, as well as selected components of the program implemented during its first 3 years. The results of 2 cross-sectional surveys of independent random samples of GPs in 1998 and 2000, to monitor cessation counselling practices, are also reported.

Program description

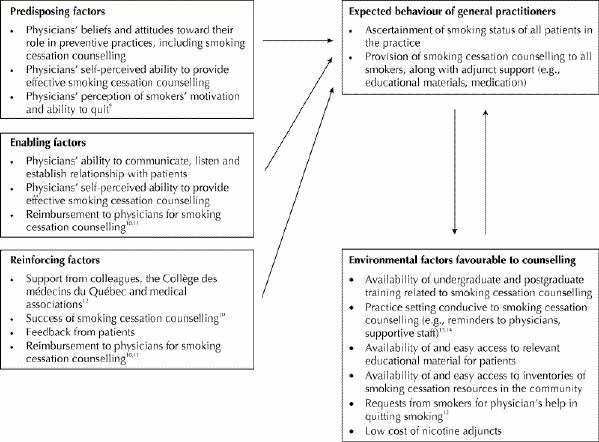

The Physicians Taking Action Against Smoking program was developed and implemented by a team of physicians (M.T., A.G. and C.L., representing one full-time equivalent position) at the Direction de la santé publique de Montréal-Centre. Program conceptualization and implementation were informed by the precede-proceed model8 and by the 5-year results of the BC Doctors' Stop-Smoking Program.3 A comprehensive literature review identified key predisposing, enabling and reinforcing factors for cessation counselling in medical practice9,10,11,12,13,14,15 (Fig. 1), each of which were targeted for intervention during the program.

Fig. 1: Theoretical model of factors affecting behaviour change in the Physicians Taking Action Against Smoking intervention program.

The target population for our program comprised all 2130 GPs practising in Montreal in 1997: 165 GPs in 29 local community health centres, 1062 GPs in group practices and 903 GPs in solo practices.

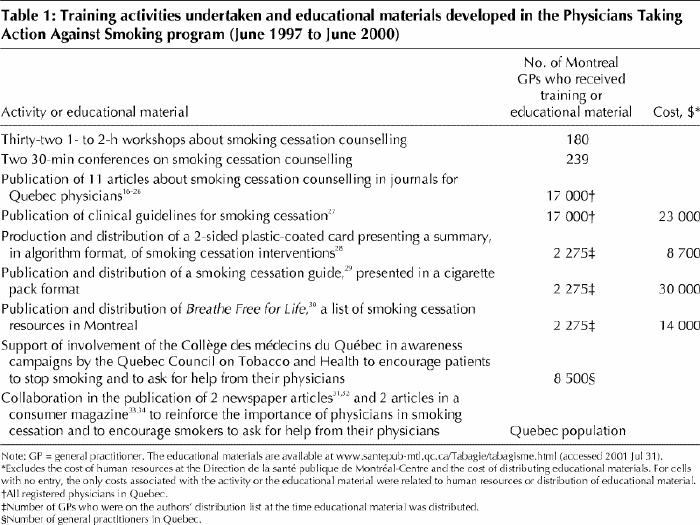

Nine distinct component activities have been developed and implemented since program inception in 1997 (Table 1), ranging in scope and intensity from collaboration with province-wide awareness campaigns to encourage smokers to quit, through a variety of publications for both physicians and the public,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34 to intensive training workshops for GPs to enhance their knowledge and skills related to smoking cessation counselling. These activities were selected to be complementary and to provide reciprocal reinforcement. Details on each activity are provided in the following paragraphs.

Table 1

Over the first 3 years of the program, 180 GPs, 37 specialists, 27 residents and 373 other health care professionals participated in a total of thirty-two 1- to 2-hour intensive training workshops designed to increase knowledge about and skills in smoking cessation counselling. Participants were recruited through word of mouth, mailings to physicians' offices and advertisements in professional interest journals, although the yield from the latter 2 recruitment strategies was low. Interest in the workshops intensified after the introduction of bupropion SR into the Canadian market in August 1998.

Workshops were moderated by trained physicians and were delivered to groups of 10 to 15 participants. Three to five clinical scenarios featuring smokers at different stages of readiness to quit were presented, and participants worked in groups of 4 or 5 to assess the cases and share their evaluations with the entire group. The moderator then described appropriate counselling interventions tailored to the smoker's stage of readiness to quit, including the use of nicotine replacement therapy and bupropion SR. During the workshops, participants were informed that billing for smoking cessation counselling is permitted by the Régie de l'assurance maladie du Québec.11 Take-home materials included a summary of the workshop, a list of smoking cessation resources in Montreal, an educational booklet to motivate smokers to stop smoking and an order form for more materials.

Two 30-minute conferences on smoking cessation counselling were provided in conjunction with continuing medical education activities organized by the Université de Montréal; a total of 239 GPs participated in these conferences. Medical students at the Université de Montréal also received training in smoking cessation counselling.

For many physicians, reading is a preferred method for remaining current with medical knowledge,35 so we published 11 articles on smoking cessation counselling in the most widely read professional interest journals in Quebec.16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26 Several of these articles addressed cessation counselling in general, and others had a more specific focus such as pharmacotherapy for withdrawal symptoms and smoking cessation among women.

Using principally the evidence-based US clinical guidelines,10 the project team developed clinical guidelines for smoking cessation counselling in collaboration with the Collège des médecins du Québec, the body responsible for monitoring the quality of medical practice in the province.27 These guidelines were ratified by the Fédération des médecins omnipraticiens du Québec, by several associations of medical specialists and by the Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux du Québec. The objectives were to establish smoking cessation counselling as a norm of good medical practice, to encourage physicians to intervene using the stages-of-change model, to encourage physicians to recommend or prescribe medications to alleviate withdrawal symptoms, and to inform physicians of resources available to assist patients in their smoking cessation efforts. The guidelines were distributed in January 1999 to all 17 000 registered physicians (both GPs and specialists) in the province of Quebec.

Practice aids and educational materials to facilitate counselling were developed in French and English and were distributed free of charge to Montreal GPs. These materials included a 2-sided, plastic-coated card depicting an algorithm that summarized optimal cessation counselling practices, according to the patient's stage of readiness to quit;28 a smoking cessation guide for patients called Freedom, presented in a cigarette pack format;29 and Breathe Free for Life, a 2-sided handout for patients containing a list of smoking cessation resources available in Montreal.30 Educational materials designed specifically for pregnant women and teenagers were also distributed to GPs.

The Physicians Taking Action Against Smoking program supported existing public awareness stop-smoking campaigns by fostering new partnerships among health organizations. For example, in January of both 1999 and 2000 our program supported the involvement of the Collège des médecins du Québec in the annual smoke-free week organized by the Quebec Council on Tobacco and Health. Information packages, including a letter signed by the presidents of the Collège des médecins du Québec and the Quebec Council on Tobacco and Health, a poster and sample pamphlets for smokers, were distributed to all GPs in Quebec. Additional patient education materials from the Quebec Council on Tobacco and Health, for display in waiting rooms, were distributed to Montreal GPs in May 1999 and May 2000.

To promote public awareness, 2 articles31,32 were published in the health column of La Presse, a popular daily newspaper in Montreal. These articles described steps to stop smoking and resources available to help smokers quit. Smokers were advised to consult their physicians for help. Finally, 2 articles on smoking cessation were published in Protégez-vous,33,34 the most popular consumer magazine in Quebec, once again promoting the role of physicians in smoking cessation and encouraging smokers to request help from their physicians.

Monitoring the smoking cessation counselling practices of GPs

Two cross-sectional surveys were conducted to monitor trends in the smoking cessation counselling practices of Montreal GPs, as well as trends in psychosocial factors related to counselling. The first survey was conducted in the period April–July 1998 and the second in April–September 2000. Data were collected by means of self-administered mailed questionnaires and included sociodemographic characteristics, beliefs and attitudes related to cessation counselling, self-perceived ability to provide effective smoking cessation counselling, perceived importance of selected barriers to counselling and use of counselling behaviours relevant to smokers at each stage of readiness to quit. In 1998, of 440 GPs randomly selected from the 1997 Collège des médecins du Québec database for Montreal and eligible to participate, 337 (76.6%) completed the questionnaire. Detailed descriptions of subject selection, sampling, data collection and study variables, as well as the results of the 1998 survey, are reported elsewhere.36 The 2000 survey was completed by 316 (69.6%) of 454 randomly selected GPs.

Respondents to the 1998 survey were younger than the respondents in 2000 (mean age 45.3 [standard deviation 9.5] v. 47.8 [standard deviation 10.4] years; p = 0.002), but the 2 groups of respondents were similar in terms of sex ratio (133 [39.5%] v. 132 [41.8%] female; p = 0.55) and language (259 [76.9%] v. 241 [76.3%] French-speaking; p = 0.86). Similar proportions had completed family medicine residency training (115 [38.6%] v. 132 [42.2%]; p = 0.37).

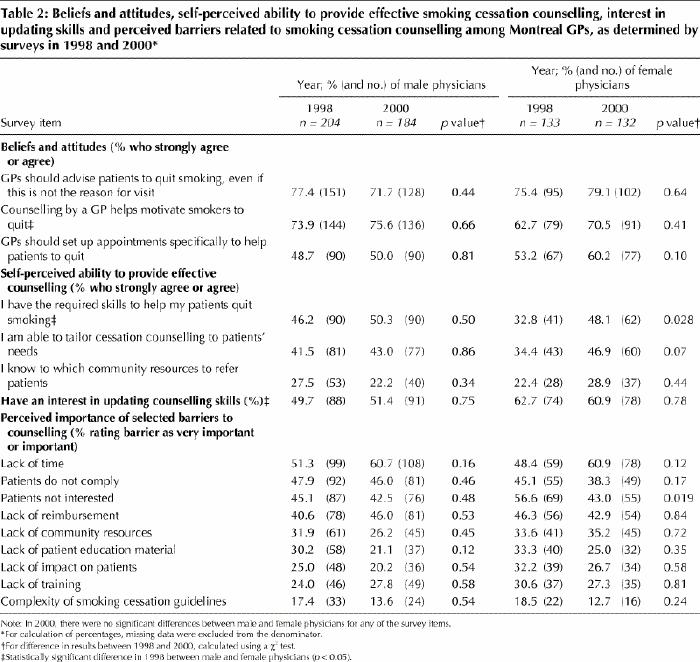

Beliefs and attitudes toward cessation counselling were generally favourable (Table 2). Self-perceived ability to provide effective counselling was low among both male and female GPs. About half of male GPs and two-thirds of female GPs were interested in updating their cessation counselling skills. Finally, GPs perceived many barriers to counselling, the most important of which was lack of time.

Table 2

There were more positive changes in psychosocial aspects of counselling among female GPs over time than among male GPs (Table 2). Specifically, the proportion of female GPs who felt that GPs should schedule specific appointments to help patients quit increased from 1998 to 2000, ratings for 2 of the 3 indicators of self-perceived ability to provide effective counselling improved among female GPs, and the perception of the importance of several barriers to cessation decreased. Notably, the perceived importance of lack of time as a barrier to counselling increased over time among both male and female GPs.

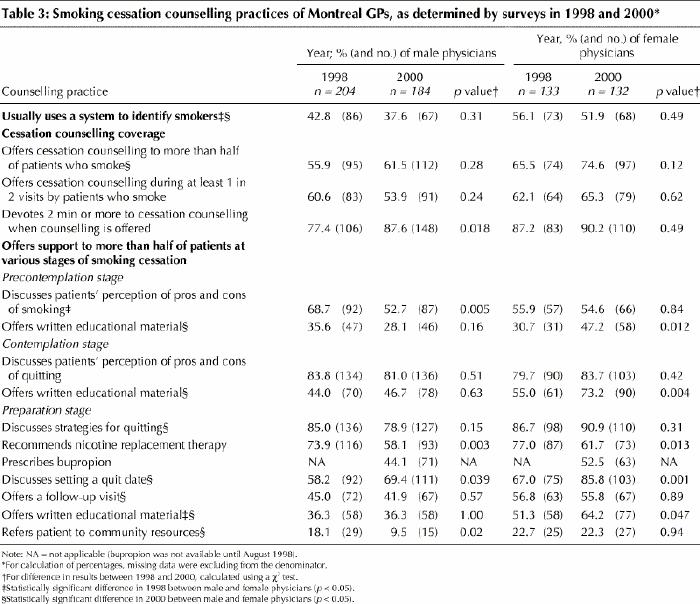

Among female GPs, several indicators of counselling behaviours improved (Table 3). For example, the proportion who offered written educational material and discussed setting a quit date increased from 1998 to 2000. The proportion of GPs, both male and female, recommending nicotine replacement therapy decreased over time, which might have been related to the introduction of bupropion SR into the market late in 1998; in 2000, 44.1% of male and 52.5% of female GPs prescribed this drug. Male GPs devoted more time to counselling and were significantly more likely to discuss setting a quit date in 2000 than in 1998. However, the proportion of male GPs who discussed the pros and cons of smoking with patients in the precontemplation stage and the proportion who referred patients in the preparation stage to community resources declined from 1998 to 2000.

Table 3

Many of the indicators of counselling behaviour suggest that female GPs' counselling practices are significantly better than those of their male counterparts, and that these differences were more pronounced in 2000 than in 1998. In 2000, a significantly greater proportion of female GPs than male GPs used a system to identify smokers, offered cessation counselling to more than half of their patients who smoked, discussed strategies for quitting, discussed setting a quit date, offered written educational material, referred patients to community resources and offered a follow-up visit.

Interpretation

Even though the implementation of the Physicians Taking Action Against Smoking program is still in progress, our experience so far suggests that it is feasible to implement a multidimensional program aimed at improving the smoking cessation counselling practices of GPs with limited resources (3 physicians working the equivalent of one full-time position and educational material estimated to cost $28 000 per year).

Although previous one-dimensional interventions aimed at physicians have failed to improve medical practice,37 our data suggest that targeting the predisposing, enabling and reinforcing factors, as suggested by our theoretical model, might potentiate the impact of the program on GPs' counselling behaviours. The absence of a control group precludes attribution of the observed positive changes to our program, but the data from 2 cross-sectional surveys conducted 2 years apart suggest improvements over time in some counselling behaviours and in several psychosocial precursors to behaviours, particularly among female GPs. The greater changes among female GPs and their greater involvement in smoking cessation counselling relative to male GPS is consistent with the results of previous research, which indicates that women are more likely to be involved in patient education.38 Although the proportion of male GPs devoting at least 2 minutes to cessation counselling and discussing setting a quit date with patients in the preparation stage increased from 1998 to 2000, fewer initiated a dialogue at the precontemplation stage in 2000 than in 1998. This may relate to the increase in perceived barriers, particularly lack of time. It is possible that male GPs focus attention on patients who are at a more advanced stage of readiness to quit. Because nicotine replacement therapy and bupropion SR are now covered by the Quebec drug insurance plan (since October 2000) and because reimbursement for medication requires a prescription, we can expect that more patients will ask physicians for cessation counselling and physicians may therefore become more responsive to educational efforts aimed at improving their skills.

Our program was implemented in a favourable social environment. Media coverage of the US lawsuits against tobacco manufacturers and of the resulting settlement, as well as reports of Canadian tobacco manufacturers' involvement in cigarette smuggling, might have helped to create a positive attitude toward stronger control of the tobacco industry. In 1998 the provincial government adopted the Quebec Tobacco Act, which sharply curtails the use of tobacco in public places. Also, province-wide mass media campaigns, including annual stop-smoking campaigns and a “quit and win” contest, have contributed to increasing public awareness of the importance of smoking cessation.

Several challenges remain in regard to improving the Physicians Taking Action Against Smoking program, most notably in addressing physicians' lack of time, perceived by many respondents as a barrier to cessation counselling. However, the positive results we have achieved to date suggest that, when combined with supportive public policy, environmental changes and mass media interventions for the public, an integrated, theory-based program to improve physicians' counselling practices could be a key component in a comprehensive strategy to reduce tobacco consumption.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Direction de la santé publique de Montréal-Centre. We thank Véronique Déry for participating in the literature review and development of the questionnaire and following up by telephone with nonrespondents. We thank Garbis Meshefedjian for analyzing the data. We thank the Collège des médecins du Québec, the Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux du Québec and GlaxoWellcome for financial support of selected components of the program. Dr. O'Loughlin is a Chercheur-boursier of the Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Competing interests: Dr. Tremblay has received an educational grant and speaker fees from GlaxoWellcome and an honorarium and travel assistance from Pegasus Health Care International. Drs. Gervais and Lacroix have received speaker fees from GlaxoWellcome. None declared for Drs. O'Loughlin, Makni and Paradis.

Correspondence to: Dr Michèle Tremblay, Direction de la santé publique, Régie régionale de la santé et des services sociaux de Montréal-Centre, 1301, rue Sherbrooke Est, Montréal QC H2L 1M3; fax 514 528-2425; mtrembl1@santepubl-mtl.qc.ca

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services. The health benefits of smoking cessation: a report of the Surgeon General. Rockville (MD): US Government Printing Office; 1990. DHHS Publ no.: (CDC) 90-8416.

- 2.Fiore MC. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence. JAMA 2000;283:3244-54. [PubMed]

- 3.Bass F. Mobilizing physicians to conduct clinical intervention in tobacco use through a medical-association program: 5 years' experience in British Columbia. CMAJ 1996;154:159-64. Available: www.cma.ca/cmaj/vol-154/0159e.htm [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Wilson D, Wilson E. Guide your patients to a smoke-free future: a program of the Canadian Council on Smoking and Health. Ottawa: Canadian Council on Smoking and Health; 1992.

- 5.Coambs RB, Jarry JL, Wilson E, Pederson L, Wong ASC, Santhiapillai A, et al. A 12 month follow-up of a dissemination study to train physicians to help patients with smoking cessation [presentation]. American Society of Addiction Medicine meeting; 1995 Oct; Toronto.

- 6.Rowan MS, Toombs M, Kothari A. Mobilizing physicians for clinical tobacco intervention in Canada: evaluating a national and provincial partnership. EvalProgram Plann 1999;22(3):331-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux. Plan d'action de lutte au tabagisme. Quebec City; Le Ministère; 1994. p. 17.

- 8.Green WL, Kreuter MW. Health promotion today and a framework for planning. In: Health promotion planning: an educational and environmental approach. 2nd ed. Moutain View (CA): Mayfield Publishing Co.; 1991. p. 1-43.

- 9.Cummings KM, Giovino, G, Sciandra R, Koenigsberg M, Emont SL. Physician advice to quit smoking: who gets it and who doesn't. Am J Prev Med 1987; 3:69-75. [PubMed]

- 10.Smoking Cessation Clinical Practice Guideline Panel and Staff. The Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Smoking Cessation Clinical Practice Guideline. JAMA 1996;275:1270-80. [PubMed]

- 11.Sullivan P, Kothari A. Right to bill may affect amount of tobacco counselling by MDs. CMAJ 1997;156:241-3. Abstract available: www.cma.ca/cmaj/vol-156/issue-2/0241.htm [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Orlandi MA, Winickoff RN, Coltin KL. Promoting health and preventing disease in health care settings: an analysis of barriers. Prev Med 1987;16:119-30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Carter WB, Belcher DW, Inui TS. Implementing preventive care in clinical practice. II. Problems for manager, clinicians and patients. Med Care Rev 1981; 38:19-24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.McDonald CJ, Hui SL, Smith DM, Tierney WM, Cohen SJ, Weinberger M, et al. Reminders to physicians from an introspective computer medical record: a two-year randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 1984;100:130-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Hutchison BG, Abelson J, Woodward CA, Norman G. Preventive care and barriers to effective prevention. How do family physicians see it? Can Fam Physician 1996;42:1693-700. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Brochu D, Tremblay M. L'usage du tabac chez les adolescents : un choix contre-indiqué. Actual Med 1997;3(1):10-2.

- 17.Lacroix C, Tremblay M. Le tabagisme au féminin. Actual Med 1997;3(1):13-8.

- 18.Lacroix C, Brochu D. Tabagisme et médicaments : un cocktail parfois interactif! Actual Med 1997;3(1):20-3.

- 19.Gervais A, Fortin M. L'intervention du médecin auprès du fumeur : comment réussir. Actual Med 1997;3(1):4-9.

- 20.Lacroix C, Ladouceur R, Tremblay M, Gervais A. «J'aide mon patient à cesser de fumer.» Omnipraticien 1999;3(8):5-18.

- 21.Tremblay M, Lacroix C. Controverses sur les traitements antitabagiques : des experts se prononcent. Clinicien 2000;15(4):124-40.

- 22.Lacroix C. Les femmes et la cigarette. Omnipraticien 2000;4(7):15-6.

- 23.Gervais A, Fortin M. Rôle du médecin et soutien pharmacologique. Actual Med 2000;21(8):33-7.

- 24.Tremblay M. Le point de vue du médecin et celui du fumeur face à l'abandon du tabac sont-ils différents? Actual Med 2000;21(6):12.

- 25.Lacroix C. L'aide aux patients fumeurs : mythes et réalités. Actual Med 2000; 21(8):13.

- 26.Gervais A. Treating tobacco use and dependence. Can J Contin Med Educ 2000; 12(8):45-65.

- 27.Clinical practice guideline: smoking prevention and cessation. Montreal: Collège des médecins du Québec, Direction de la santé publique de la Régie régionale de la santé et des services sociaux de Montréal-Centre; 1999.

- 28.Tobacco use. In: Prévention en pratique médicale. Montreal: Direction de la santé publique de la Régie régionale de la santé et des services sociaux de Montréal-Centre, Association des médecins omnipraticiens de Montréal; 1998.

- 29.Freedom: 25 pages of smoker information. Montreal: Direction de la santé publique de la Régie régionale de la santé et des services sociaux de Montréal-Centre; 1999.

- 30.Breathe free for life. Stop smoking resource guide — Montreal region. Montreal: Direction de la santé publique de la Régie régionale de la santé et des services sociaux de Montréal-Centre; 1998.

- 31.Collège des médecins du Québec. Pour cesser de fumer, mieux vaut se préparer. La Presse [Montreal] 1999 Jan 17;SectC:3.

- 32.Collège des médecins du Québec. Une période idéale pour arrêter de fumer. La Presse [Montreal] 1999 Jan 16;SectC:3.

- 33.Sabourin G. Comment écraser? Protégez-vous 1998 Jan. p. 29–34.

- 34.Frisko P. La pilule des accros. Protégez-vous 2000 May. p. 12-3.

- 35.Dongeois M. La formation continue au Québec. Actual Med 1997;18(14):2-23.

- 36.O'Loughlin J, Makni H, Tremblay M, Lacroix C, Gervais A, Déry V, et al. Smoking cessation counseling practices of general practitioners in Montreal. Prev Med. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Oxman AD, Thomson MA, Davis DA, Haynes B. No magic bullets: a systematic review of 102 trials of interventions to improve professional practice. CMAJ 1995; 153:1423-31. Available: www.cma.ca/cmaj/vol-153/issue-10/1423.htm [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Woodward CA, Hutchison BG, Abelson J, Geoffrey N. Do female primary care physicians practise preventive care differently from their male colleagues? Can Fam Physician 1996;42:2370-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed]