Abstract

Background

Loss of mismatch repair (MMR) occurs frequently in endometrial carcinoma (EC) and is an important prognostic marker. However, the frequency of MMR deficiency (D-MMR) in EC remains inconclusive. This systematic review and meta-analysis addressed this inconsistency and evaluated related clinicopathology.

Methods

Electronic databases were searched for articles: PubMed, Science Direct, Web of Science, EMBASE, and the Wiley Online Library. Data were extracted from 25 EC studies of D-MMR to generate a clinical dataset of 7,459 patients. A random-effects model produced pooled estimates of D-MMR EC frequency with 95% confidence interval (CI) for meta-analysis.

Results

The overall pooled proportion of D-MMR was 24.477% (95% CI, 21.022 to 28.106) in EC. The Lynch syndrome subgroup had 22.907% pooled D-MMR (95% CI, 14.852 to 32.116). D-MMR was highest in type I EC (25.810) (95% CI, 22.503 to 29.261) compared to type II (13.736) (95% CI, 8.392 to 20.144). Pooled D-MMR was highest at EC stage and grades I–II (79.430% and 65.718%, respectively) and lowest in stages III–IV and grade III (20.168% and 21.529%). The pooled odd ratios comparing D-MMR to proficient MMR favored low-stage EC disease (1.565; 0.894 to 2.740), lymphovascular invasion (1.765; 1.293 to 2.409), and myometrial invasion >50% (1.271; 0.871 to 1.853).

Conclusions

Almost one-quarter of EC patients present with D-MMR tumors. The majority has less aggressive endometrioid histology. D-MMR presents at lower tumor stages compared to MMR-proficient cases in EC. However other metastatic parameters are comparatively higher in the D-MMR disease setting.

Keywords: Microsatellite instability, MMR-D, Endometrial carcinoma

Endometrial carcinoma (EC) is the most common cancer of the female genital tract [1]. The majority of endometrial cancers is sporadic (90%), while up to 5% are inherited cases such as Lynch syndrome. In the United States, there are approximately 60,000 new cases and 10,470 deaths per year [1]. The reason for the increasing worldwide trend of EC incidence is ill-defined. However, one possibility is an increase in aggressive uterine cancer subtypes. In 2013, the Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (TCGA) classified EC into four molecular subgroups that correlated with survival [2,3]. The subgroups were ranked from best to worse prognosis as (1) ultra-mutated (POLE-mutated), (2) hypermutator phenotype caused by mismatch repair deficiency (D-MMR) that also features microsatellite instability (MSI), and (3) either a copy number low, or (4) high phenotype. Tumors with D-MMR can have a more favorable prognosis [2], despite the advantages offered by a proficient MMR system.

Indeed, MMR plays a critical role during DNA replication by recognizing and fixing incorrectly paired nucleotides. This safeguarding of DNA integrity prevents mutagenesis and cancer development. Most sporadic EC cases are caused by genetic alterations that cause loss of MMR proteins (D-MMR) [4]. Tumors with D-MMR also feature the concordant molecular fingerprint of MSI. There are now up to seven identified human genes that function as a multi-subunit complex to facilitate MMR: hMLH1, hMLH3, hMSH2, hMSH3, hMSH6, hPMS1, and hPMS2. In sporadic endometrial cancers, deficient MMR typically arises from hypermethylation of the hMLH1 gene promoter region, as reviewed by Nojadeh et al. [5]. Furthermore, inherited Lynch syndrome cases are caused by a germline heterozygous mutation in one of the four MMR genes—hMLH1, hMSH2, hMSH6, and hPMS2 [4].

Disruption of MMR pathway genes in EC causes loss of key proteins (D-MMR) that is measurable using immunohistochemistry (IHC) and/or molecular approaches. However, there is a wide disparity in D-MMR frequency reported using IHC and molecular studies of EC—ranging from 6.612% to 43.351% [6-30]. This meta-analysis aimed to consolidate the conflicting estimates to report overall frequency of D-MMR in EC. In principle, the final estimate of D-MMR proportion in EC might be affected by inclusion of germline mutation cases. This possibility was investigated by subgroup analysis of Lynch syndrome cases. Furthermore, EC has been historically classified into estrogendependent (type I) cancer with a more favorable prognosis or as independent (type II) cancers that are typically less common and more aggressive [31]. Both D-MMR frequencies in type I and type II endometrial tumors were estimated by meta-analysis. Finally, the clinicopathologic characteristics were pooled to determine the prognostic value of the D-MMR subtype.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

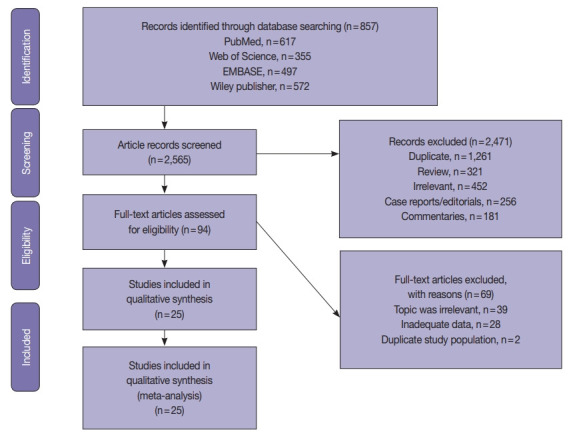

Systematic review

The systematic review was conducted according to the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [32]. The PRISMA flow chart for search strategy leading to meta-analysis is illustrated in Fig. 1. The following databases were searched independently by two reviewers (ASJ and HSAH): PubMed, Science Direct, Web of Science, EMBASE, and the Wiley Online Library from inception to March 1, 2020. The search terms included the following: “Endometrial cancer” OR “endometrial carcinoma” OR “uterine cancer” “Mismatch repair gene” OR “hMLH1” OR “hMSH2” OR “hMSH3” OR “hMSH6” OR “hPMSH1” OR “hPMSH2” OR MMR. The references within the included studies were screened to identify suitable publications. The search was not limited by date or language. Two reviewers (ASJ and HSAH) assessed the title and abstracts of the studies, and full texts were retrieved to determine eligible studies. The eligibility criterion was applied independently by the other two authors (AAY and MMS). Any disagreements in selection of studies were resolved by consensus under guidance of the senior author.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart for search strategy, leading to selection of 25 studies for meta-analysis.

Study inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria used were (1) diagnosed with EC, (2) expression of MMR-related genes was measured using IHC and/or molecular methods such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in the EC, (3) the proportion of MMR in EC was investigated, and (4) publication as a full paper. There were no limits applied for language, and any foreign papers were translated. When the same team reported several studies from the same patients, the most recent was included. Case reports, review articles, and studies published in abstract format only were excluded.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) did not sufficiently meet all of the abovementioned inclusion criteria, (2) duplicate publication or data, and (3) single case reports, commentaries, review articles, editorials, and unrelated articles or letters to the editor.

Data collection

Two authors extracted eligible study data of (1) first author name and year of publication, (2) study participant data (total number of cases, number of D-MMR mutant ECs, histological type (endometrioid vs. non-endometrioid), stage and grade of disease, and extent of myometrial and lymphovascular invasion [LVI]), and (3) MMR characteristic data (gene subtype test method and study country of origin). Articles that did not display the relevant data were recorded as ‘not reported.’ Any disagreements regarding collection and refinement of data were discussed between the two authors under direction of the senior author.

Study quality assessment

The Quality Assessment Tool for Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 (QUADAS-2) [33] was used to assess study quality. The tool comprises four domains of “patient selection,” “index test,” “reference standard,” and “flow and timing.” Each domain was considered in terms of risk of bias, and the first three domains were used to examine study applicability. Risk of bias and applicability were assessed with signaling questions as “yes,” “no,” or “unclear.” The final result categorizing risk of bias was “high,” “low,” or “unclear.”

Meta-analysis and statistical methods

Mismatch repair alterations were analyzed in both EC types. Type I included endometrioid and mucinous types, while type II included any other variants [34]. The meta-analysis was conducted using MedCalc statistical software [35] according to PRISMA [32]. The pooled proportion of D-MMR was calculated using the random effect model [36] for meta-analysis. The heterogeneity test used the inconsistency index (I2) [36,37] and Q statistic, for which a p-value less than .1 was considered to represent significant heterogeneity. The I2 represents the proportion of total variation contributed by between-study variations. The level of heterogeneity was considered low (I2=25%), medium (I2=50%), or high (I2=75%). The types and histological variants were pooled, and results were reported with 95% confidence interval. Publication bias was assessed using a visual method by funnel plot tests [38]. A subgroup analysis was performed according to detection method of (1) IHC alone or (2) molecular technique. A further subgroup analysis was performed according to the study country of origin—whether based in Western or Asian countries. In addition, subgroup analysis was performed for studies that included cases diagnosed with Lynch syndrome. Sensitivity analysis was performed by removing each result in turn and reestimating the pooled proportion to assess the influence of the data removed on final calculations and the robustness of observations.

RESULTS

Study characteristics and quality assessment

A total of 2565 EC studies were identified to clarify D-MMR, as shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1). Of the 2471 excluded, 1261 were duplicates, 452 were irrelevant based on title or abstract; 321 reviews, 256 case reports or editorials, and 181 commentaries were unsuitable. The remaining 94 articles were evaluated by reading the full-text, and further 69 were excluded (39 were irrelevant, 28 lacked data, and 2 had duplicate study populations). A final 25 eligible studies [6-30] were included for quantitative meta-analysis (Fig. 1). The studies comprised a total of 7,459 EC patients, of which D-MMR presented in 1783. The study characteristics, including individual D-MMR proportion (%) and clinicopathological features, are presented in Table 1. Quality assessment of studies was performed using QUADAS-2. Most studies showed low risk of bias and applicability concerns (Supplementary Figs. S1, S2).

Table 1.

The characteristics and clinicopathology of the included 25 studies for meta-analysis

| Study | Sample size | D-MMR EC (%) | Study site | Detection method and D-MMR marker | Clinicopathologic characteristics |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-MMR subjects Grade I-II EC | D-MMR Grade III EC | D-MMR Stage I-II EC | D-MMR Stage III-VI EC | D-MMR subjects with MI < 50%a | D-MMR subjects with MI > 50%b | D-MMR EC with positive LVI | |||||

| Buchanan et al. (2014) [6] | 702 | 24.501 | Australia | IHC amarkers: MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2 (protein loss or presence) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Stelloo et al. (2016) [7] | 834 | 26.259 | Nether-lands | IHC markers: MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2 proteins | NR | NR | NR | NR | 148 | 71 | 19 |

| An et al. (2007) [8] | 93 | 18.280 | South Korea | PCR | 12 | 5 | NR | NR | 7 | 10 | 7 |

| Arabi et al. (2009) [9] | 91 | 27.473 | USA | IHC markers: MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 proteins | NR | NR | 13 | 12 | 15 | 10 | 14 |

| Auguste et al. (2018) [10] | 102 | 20.588 | USA, Canada | IHC markers: MLH1, MLH2, MSH6, PMS2 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Basil et al. (2000) [11] | 229 | 30.568 | USA | PCR markers: BAT26, BAT25, D5S346, D2S123, D17S250 | NR | NR | 61 | 9 | NR | NR | NR |

| Bosse et al. (2018) [12] | 376 | 43.351 | USA, Canada, UK | IHC markers: MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMSU proteins | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Broaddus et al. (2006) [13] | 138 | 18.841 | USA | IHC markers: MLH1 and MSH2 (n = 50) sequencing of MLH1 and MSH2 genes | NR | NR | 16 | 10 | NR | NR | 14 |

| Cohn et al. (2001) [14] | 210 | 24.286 | USA | PCR markers: BAT-25, BAT-26, D5S346, D2S123, D17S250 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| de Jong et al. (2012) [15] | 463 | 33.477 | Netherlands | IHC markers: MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 proteins | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 98 |

| Hirai et al. (2008) [16] | 120 | 15.000 | Japan | Sequencing of MLH1, MLH2, MSH6 genes | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Huang et al. (2015) [17] | 42 | 28.571 | Taiwan | IHC (MLH1, PMS2, MSH6, and MSH2), PCR (BAT-25, BAT-26, NR-21, NR-24, and MONO-27) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Black et al. (2006) [18] | 473 | 19.662 | USA | PCR markers: BAT25, BAT26, D2S123M, D5S346, D17S250 | 72 | 21 | 77 | 16 | 67 | 25 | 30 |

| Nagle et al. (2018) [19] | 698 | 19.198 | Australia | IHC (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2), MLH1 methylation testing was conducted for all cases with MLH1/PMS2 loss | NR | NR | 125 | 17 | NR | NR | 47 |

| Kommoss et al. (2018) [20] | 452 | 28.097 | USA, Canada, Germany | IHC to detect MMR protein loss in markers PMS2 and MSH6 | 102 | 25 | NR | NR | 44 | 58 | 25 |

| Mackay et al. (2010) [21] | 163 | 19.632 | Canada | PCR testing of MSI, markers are BAT25/26 | 21 | 11 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Maruyama et al. (2001) [22] | 146 | 36.301 | Japan | IHC marker MSH2, MLH1 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Mills et al. (2014) [23] | 605 | 6.612 | USA | IHC of MLH1, MSHU, MSH6, PMS2 proteins, PCR confirmation of MLH1/PMS2 DNA methylation | 26 | 9 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Djordjevic et al. (2013) [24] | 186 | 24.731 | USA | IHC detection of MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2 proteins, PCR confirmation of MLH1 methylation to confirm loss of MLH1 protein | 28 | 8 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Okoye et al. (2016) [25] | 411 | 27.981 | USA | IHC to detect loss of MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, PCR confirmation of MLH1 methylation | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Ruiz et al. (2014) [26] | 212 | 30.189 | Spain | IHC of MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2 markers | 58 | 16 | 50 | 10 | 50 | 14 | 6 |

| Shikama et al. (2016) [27] | 221 | 28.054 | Japan | IHC of MMR proteins MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2 | NR | NR | 39 | 18 | NR | NR | 27 |

| PCR confirmation of MLH1 methylation | |||||||||||

| Stelloo et al. (2015) [28] | 116 | 16.379 | Europe | IHC of MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, PCR MLH1 methylation confirmation | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Promega (ver. 1.2) PCR testing of MSI markers | |||||||||||

| Talhouk et al. (2016) [29] | 57 | 31.579 | Canada, USA | IHC of MMR proteins MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2 | 10 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 7 |

| Talhouk et al. (2017) [30] | 319 | 9.718 | Canada | IHC for presence or absence MMR proteins MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 28 |

D-MMR, MMR deficiency; EC, endometrial carcinoma; MI, myometrial invasion; LVI, lymphovascular invasion; IHC, immunohistochemistry; NR, not reported; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; MMR, mismatch repair; MSI, microsatellite instability.

MI < 50%: MI is less than 50% of the total myometrial thickness;

MI > 50%: MI is greater than 50% of the total myometrial thickness.

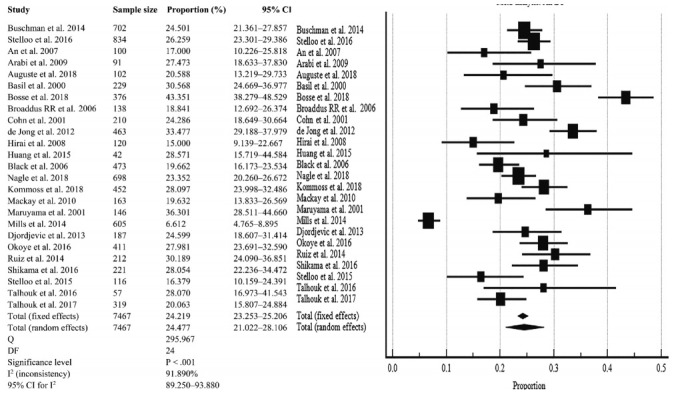

Meta-analysis of pooled D-MMR in EC

The pooled prevalence of D-MMR tumors in EC in 25 studies comprising the 7467 patients was calculated as 24.477% (95% confidence interval [CI], 21.022 to 28.106) (Table 2, Fig. 2). There was significant heterogeneity between all the studies (I2=91.890%; 95% CI, 89.250 to 93.880) (Fig. 2). To minimize heterogeneity, a conservative approach to the present meta-analysis was selected using the random effect model. Publication bias was investigated using the funnel plot [38] as depicted in Supplementary Fig. S3.

Table 2.

The association between D-MMR EC and clinicopathological characteristics

| Clinicopathological characteristics in EC | Pooled % portion (95% CI) | No. of studies | I2 (95% CI, %) | p-value | Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall D-MMR mutation | 24.477 (21.022–28.106) | 25 | 91.890 (89.250–93.880) | < .001 | Random effect |

| D-MMR mutation in type I | 25.810 (22.503–29.261) | 14 | 80.440 (68.080–88.020) | < .001 | Random effect |

| D-MMR mutation in type II | 13.736 (8.392–20.144) | 10 | 77.320 (58.360–87.650) | < .001 | Random effect |

| Stage I–II | 79.430 (71.500–86.357) | 6 | 68.640 (25.980–86.710) | .007 | Random effect |

| Stage III–IV | 20.168 (13.746–27.469) | 6 | 61.850 (7.020–84.350) | .022 | Random effect |

| Grade I–II | 65.718 (52.602–77.714) | 10 | 91.700 (86.860–94.760) | < .001 | Random effect |

| Grade III | 21.529 (15.930–27.718) | 10 | 94.050 (90.97–96.08) | < .001 | Random effect |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 32.105 (21.371–43.896) | 10 | 91.380 (86.270–94.590) | < .001 | Random effect |

| MI less than 50% | 51.807 (38.514–64.971) | 8 | 89.860 (82.410–94.150) | < .001 | Random effect |

| MI more than 50% | 42.346 (28.576–56.750) | 8 | 91.360 (85.380–94.890) | < .001 | Random effect |

D-MMR, mismatch repair deficiency; EC, endometrial carcinoma; CI, confidence interval; MI, myometrial invasion.

Fig. 2.

The D-MMR gene proportions in each study are shown by forest plot [6-30]. D-MMR, mismatch repair deficiency; CI, confidence interval; EC, endometrial carcinoma.

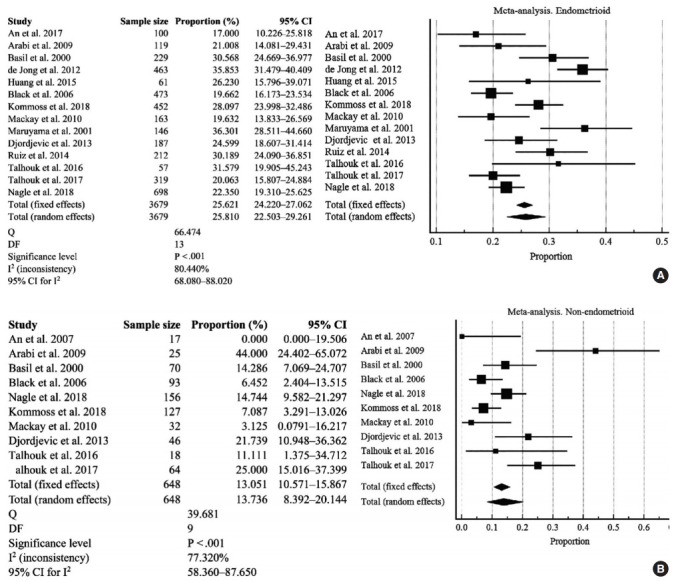

Analysis of EC type I and type II variants

There were 14 studies investigated for D-MMR alterations in type I EC, with a total of 3679 patients (Fig. 3A). The pooled proportion of D-MMR using the random effect model was 25.810% (95% CI, 22.503 to 29.261) (Table 2). The heterogeneity between the studies was significant (I2=80.440%; 95% CI, 68.080 to 88.020). There were 10 studies investigated for D-MMR alterations in type II EC, with a total of 648 patients (Fig. 3B). The meta-analysis determined a lower pooled D-MMR proportion of 13.736% (95% CI, 8.392 to 20.144) in type II EC (Table 2). The heterogeneity test was significant (I2=77.320%; 95% CI, 58.360 to 87.650). The pooled odds ratio of type I EC endometrioid histology in D-MMR versus MMR-proficient tumors was 1.389 (95% CI, 0.519 to 3.720) (Table 3). In contrast, the pooled odds ratio for the more aggressive type II non-endometrioid histology was 0.450 (0.349 to 0.579) (Table 3). These findings indicate that D-MMR EC tumors tend to present with less aggressive endometrioid histology compared to MMR-proficient tumors.

Fig. 3.

D-MMR EC: type I EC (A) and type II EC (B) [8,9,11-15,17-22,24,26,29,30]. D-MMR, mismatch repair deficiency; CI, confidence interval; EC, endometrial carcinoma.

Table 3.

Pooled odds ratio of clinicopathologic variables in D-MMR EC vs. wild type

| Clinicopathology D-MMR EC vs. wild type | Pooled odds ratio (95% CI) | No. of studies | I2 (95% CI, %) | p-value for I2 | Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage I–II EC | 1.565 (0.894–2.740) | 6 | 70.100 (30.040–87.220) | .005 | Random effect |

| Stage III–V EC | 0.936 (0.593–1.478) | 6 | 51.210 (0.000–80.580) | .068 | Random effect |

| Grade I–II EC | 0.706 (0.257–1.940) | 9 | 94.400 (91.360–96.370) | < .001 | Random effect |

| Grade III EC | 1.384 (0.806–2.375) | 7 | 69.430 (32.800–86.100) | .003 | Random effect |

| LVI | 1.765 (1.293–2.409) | 10 | 51.590 (0.530–76.440) | .028 | Random effect |

| MI less than 50% | 1.230 (0.849–1.782) | 8 | 65.900 (27.620–83.930) | .004 | Random effect |

| MI more than 50% | 1.271 (0.871–1.853) | 8 | 65.750 (27.250–83.870) | .004 | Random effect |

| Type I endometrioid histology | 1.389 (0.519–3.720) | 10 | 92.130 (87.630–95.000 | < .001 | Random effect |

| Type II non-endometrioid histology | 0.450 (0.349–0.579) | 10 | 31.500 (0.000–67.300) | .156 | Fixed effect |

D-MMR, mismatch repair deficiency; EC, endometrial carcinoma; CI, confidence interval; LVI, lymphovascular invasion; MI, myometrial invasion.

Subgroup analysis according to methodology, country, and Lynch syndrome

High heterogeneity was noted in the subgroup analysis (I2 >75%) (Supplementary Figs. S4, S5). The IHC method alone (Supplementary Fig. S4B) had the highest pooled proportion of D-MMR at 27.918% (95% CI, 22.608 to 33.558), whereas studies involving molecular approaches had less frequent DMMR (20.875%; 95% CI, 16.514 to 25.602) (Supplementary Fig. S4A). Studies from Asian countries had a slightly higher D-MMR proportion of 25.112% (95% CI, 17.675 to 33.370) in comparison to Western countries (at 23.666%; 95% CI, 19.519 to 28.080) (Supplementary Fig. S5A, B). Some studies included both sporadic EC and germline mutation (Lynch syndrome-associated) cases. Since the presence of germline mutation can affect the final estimate of D-MMR proportion in EC, a subgroup analysis was performed. All cases of D-MMR EC involving Lynch syndrome were grouped together and resulted in a proportion of 22.907% (95% CI, 14.852 to 32.116). Although subgroup heterogeneity was high, with I2 (inconsistency) of 95.970% (95% CI, 93.680 to 97.440) (Supplementary Fig. S6), inclusion of Lynch cases did not significantly affect overall DMMR estimates.

D-MMR and clinicopathological characteristics

The EC clinicopathological characteristics are shown in Supplementary Fig. S7–S14, and Tables 2 and 3 for D-MMR tumors. There was substantial heterogeneity in the majority of clinicopathologic findings.

EC tumor stage and grade

The pooled proportion of D-MMR presented at higher levels in earlier stages of EC (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. S7A, B). Stage I–II EC cases had high D-MMR level of 79.430% (95% CI, 71.500 to 86.357) that decreased to 20.168% (95% CI, 13.746 to 27.469) by stages III–IV. The pooled odds ratio of stage I–II D-MMR EC versus wild type was 1.565 (95% CI, 0.894 to 2.740), while that for stages III–IV was 0.936 (95% CI, 0.593 to 1.478) (Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. S8A, B). As shown in Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. S9A and B, the pooled proportion of D-MMR in grade I–II tumors was high at 65.718% (95% CI, 52.602 to 77.714) and decreased to 21.529% in more aggressive grade III tumors (95% CI, 15.930 to 27.718). However, the pooled odds ratio of grade I–II in D-MMR EC versus wild type tumors was 0.706 (95% CI, 0.257 to 1.940) (Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. S10A, B), with high heterogeneity (I2=94.400%; 95% CI, 91.360 to 96.370). These findings indicate that D-MMR EC tumors present with higher grades at lower tumor stages compared to MMR-proficient tumors.

Lymphovascular and myometrial invasion in D-MMR tumors

The pooled proportion of LVI in D-MMR EC was 32.105% (95% CI, 21.371 to 43.896), as shown in Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. S11. The pooled odds ratio of LVI in D-MMR EC versus proficient one MMR was 1.765 (95% CI, 1.293 to 2.409) (Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. S12). This implies that MMRproficient EC tumors have reduced the likelihood of LVI compared to D-MMR cases. The myometrial invasion (MI) data are shown in Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. S13. The pooled proportion of MI detected at less than 50% of the myometrium was 51.807% (95% CI, 38.514 to 64.971), and while that in >50% of myometrium was 42.346% (95% CI, 28.576 to 56.750). The pooled odds ratio of MI <50% in D-MMR EC versus proficient MMR EC was 1.230 (95% CI, 0.849 to 1.782), while that for MI > 50% in D-MMR EC versus proficient MMR EC was 1.271 (95% CI, 0.871 to 1.853) (Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. S14).

Sensitivity analysis

Selected data removal did not affect the final estimation of DMMR level by meta-analysis, indicating robustness of the final results. The meta-analysis was repeated after omitting studies with small sample size (< 100 and < 200). For sample sizes < 100, the pooled D-MMR level was 23.765% (95% CI, 19.604 to 28.194), and that for sample sizes < 200 was 24.454% (95% CI, 19.308 to 29.997) (Supplementary Fig. S15). Further sensitivity analysis was performed after omitting studies dealing with Lynch syndrome. The pooled proportion of D-MMR EC after exclusion of Lynch cases was 25.272 (22.089 to 28.594) (Supplementary Fig. S16). There was no significant difference from the estimated pooled proportion of D-MMR EC of any studies included in this meta-analysis (24.477%, 95% CI, 21.022 to 28.106) (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

DISCUSSION

The integrity of the genome is maintained by the MMR system that recognizes and repairs base mismatches and insertion/deletion errors generated during DNA replication and recombination. A defective MMR system results in genome-wide instability and progressive accumulation of mutations. This mainly occurs at regions of simple repetitive DNA sequences known as microsatellites, causing MSI [39,40]. The risk of carcinogenesis is greatly increased when mutations occur in tumor suppressor genes [41], as evidenced by the incidence of EC worldwide [42]. The majority of sporadic cases is caused by defective MMR and the resultant MSI that leads to mutagenesis and carcinogenesis [43]. However, in the era of personalized medicine, knowledge of the MMR-related phenotype can provide invaluable prognostic information to protect patient health. The TCGA has classified endometrial cancers into four molecular subtypes that impact on prognosis—including an MSI hyper-mutated (D-MMR) genomic group [2]. Talhouk et al. [29] later showed that MMR assessment by IHC can accurately detect the related (TCGA) MSI molecular subtype. The IHC approach showed that defective MMR is confirmed by absence of MMR proteins (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2) after sequential immunostaining of the tumor specimen. MMR deficiency is typically evaluated using IHC to determine MMR protein expression levels and is confirmed by PCR assessment of MLH1 promotor methylation and MSI markers. This present meta-analysis pooled many studies [6-30] with D-MMR frequency variations (6.610% to 43.351%) to determine the overall frequency of D-MMR. Our meta-analysis consolidated the proportions of D-MMR in relation to clinicopathological markers of prognostic value for EC patients.

The meta-analysis concludes that 24.477% EC patients harbor tumors with D-MMR. The defective MMR pathway was most prevalent in EC type I (25.810%) compared to type II (13.736%). The D-MMR EC tumors tend to present with less aggressive endometrioid histology compared to MMR-proficient tumors (odds ratio, 1.389).

The clinicopathologic characteristics that present in EC tumors with D-MMR are variable and have implications for treatment. For instance, D-MMR EC tumors presented at lower tumor stages compared to MMR-proficient cases (odds ratio, 1.565) and grades I–II tumors at higher stages (65.718%). However, the pooled odds ratio of low grades (I–II) in D-MMR compared to wild type favors the intact MMR system (odds ratio, 0.706). The clinical parameter of LVI is a marker of metastatic potential in cancer patients and was noted in 32.105% of endometrial cancers with D-MMR. The pooled odds ratio of LVI in D-MMR EC versus proficient was 1.765, suggesting that metastasis is more likely in D-MMR tumors. Furthermore, 42.346% of D-MMR EC had deep myometrial involvement that was defined as invasion >50%. The pooled odds ratio of MI >50% in D-MMR EC versus that in proficient MMR EC was 1.271. This suggests that the opportunity for extrauterine disease is greater in EC tumors with mismatch repair deficiency. The literature reports that MSI tumors can progress quickly to the metastatic stage and respond poorly to chemotherapies [44,45]. Yet, D-MMR cancers can have a more favorable prognosis compared with MMR-proficient counterparts [46]. MSI EC tumors do have a protective immune phenotype and positively correlate with high immune infiltration. In theory, this protective immune phenotype can counteract the poor clinicopathological parameters that co-exist in DMMR tumors.

Overall, the value of the MMR-related phenotype in EC provides an impetus for developing treatment approaches that target its tumor-specific molecular characteristics. Further investigations to clarify the involvement of MMR in EC etiology are vital for improved clinical decision making and selecting optimal patient treatment options. In colorectal cancer [47], some chemotherapeutic regimens have demonstrated improved treatment efficacy and amelioration of drug toxicity in D-MMR tumors. These findings highlight the importance of this molecular subset of tumors harboring D-MMR and MSI and the potential translation into improved clinical management of EC.

There are several study limitations to discuss. First, the detection methods for D-MMR were different between studies—some used IHC alone and others used a molecular approach. The definition of aberrant MMR in studies was inconsistent with that in IHC testing. There are studies that consider MMR expression negative when there is aberrant MMR, while others regard MMR expression as absent with negative expression of hMLH1 or hMLH2. MSI testing (IHC and methylation) for endometrial cancer is used mostly for sporadic cases. However, studies in this meta-analysis used sequencing methods mainly for Lynch syndrome. This could be a source of potential bias or limitation. The studies including cases with Lynch syndrome might affect the final pooled proportion of D-MMR EC. To address this, a Lynch subgroup analysis was carried out, along with a sensitivity analysis by omitting cases with Lynch syndrome.

Second, there was significant heterogeneity across the meta-analysis that was unresolved by subgroup analysis.

The documented variation in D-MMR can be attributed to differences in ethnicity and geographical distribution. Again, our analysis showed significant heterogeneity between the selected studies for our analysis. This finding is expected and noted in other meta-analysis studies of different cancer types [45]. The heterogeneity is probably caused by differences in population characteristics, number of cases (sample size), and differences in the number of markers used to evaluate MMR. Our study also tried to evaluate the role of population characteristics cited in each scientific paper (e.g., racial and ethnic background) in regard to D-MMR. However, this objective was not possible because the parameters were not documented clearly for consideration in our study. To solve the problem of heterogeneity, a conservative approach using a random effect model was chosen. The sensitivity analysis omitted studies with small sample size (less than 100 and 200, respectively), and the re-estimated pooled proportions did not differ from the original calculations.

Furthermore, one of the pitfalls of any meta-analysis is publication bias or missed relevant articles during searches. To avoid this, we used strict criteria to limit missed papers. Any source of publication bias or non-significant findings were clarified using funnel plots. The scatter was located at the very top of the funnel, indicating absence of significant bias.

Our meta-analysis of D-MMR frequency consolidates wide published variations and is reflective of the MSI status in EC. The D-MMR pathway is very important for development of MSI and the pathogenesis of EC; most significantly for type I tumors. Although D-MMR causes a mix of clinicopathological features, this molecular subtype is linked to improved survival prospects in women with endometrial disease. These findings have clinical relevance for guiding treatment of EC patients with D-MMR tumors. Lastly, further efforts are required to evaluate and characterize the hormonal and environmental factors in women diagnosed with D-MMR EC. Such studies are imperative to provide researchers insight into possible interactions between genetic and environmental factors that contribute to development of this devastating disease of the female reproductive system.

Footnotes

Ethics Statement

All procedures performed in the current study were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Kufa (IRB No.2019-01- 500) in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments and revision in 2013. Formal written informed consent was not required after a waiver by the University of Kufa Research Ethics Committee.

Availability of Data and Material

All data generated or analyzed during the study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

CConceptualization: ASJ, MMS. Data curation: ASJ. Formal analysis: ASJ, MMS. Methodology: ASJ, HSAH, MMS. Project administration: HSAH, MMS. Resources: HSAH. Software: ASJ, MMS. Supervision: ASJ, AAY. Validation: MMS, HSAH. Visualization: HSAH, MMS. Writing—original draft: ASJ, AAY, KAM. Writing—review & editing: AAY, ASJ, KAM, HSAH. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

No funding to declare.

Supplementary Materials

The Data Supplement is available with this article at https://doi.org/10.4132/jptm.2021.02.19.

Supplementary Fig. S1

Supplementary Fig. S2

Supplementary Fig. S3

Supplementary Fig. S4

Supplementary Fig. S5

Supplementary Fig. S6

Supplementary Fig. S7

Supplementary Fig. S8

Supplementary Fig. S9

Supplementary Fig. S10

Supplementary Fig. S11

Supplementary Fig. S12

Supplementary Fig. S13

Supplementary Fig. S14

Supplementary Fig. S15

Supplementary Fig. S16

References

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network; Kandoth C, Schultz N, et al. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013;497:67–73. doi: 10.1038/nature12113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Church DN, Stelloo E, Nout RA, et al. Prognostic significance of POLE proofreading mutations in endometrial cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:402. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell DW, Ellenson LH. Molecular genetics of endometrial carcinoma. Annu Rev Pathol. 2019;14:339–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020117-043609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nojadeh JN, Behrouz Sharif S, Sakhinia E. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. EXCLI J. 2018;17:159–68. doi: 10.17179/excli2017-948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchanan DD, Tan YY, Walsh MD, et al. Tumor mismatch repair immunohistochemistry and DNA MLH1 methylation testing of patients with endometrial cancer diagnosed at age younger than 60 years optimizes triage for population-level germline mismatch repair gene mutation testing. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:90–100. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stelloo E, Nout RA, Osse EM, et al. Improved risk assessment by integrating molecular and clinicopathological factors in early-stage endometrial cancer-combined analysis of the PORTEC cohorts. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:4215–24. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.An HJ, Kim KI, Kim JY, et al. Microsatellite instability in endometrioid type endometrial adenocarcinoma is associated with poor prognostic indicators. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:846–53. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213423.30880.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arabi H, Guan H, Kumar S, et al. Impact of microsatellite instability (MSI) on survival in high grade endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;113:153–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Auguste A, Genestie C, De Bruyn M, et al. Refinement of high-risk endometrial cancer classification using DNA damage response biomarkers: a TransPORTEC initiative. Mod Pathol. 2018;31:1851–61. doi: 10.1038/s41379-018-0055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basil JB, Goodfellow PJ, Rader JS, Mutch DG, Herzog TJ. Clinical significance of microsatellite instability in endometrial carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;89:1758–64. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001015)89:8<1758::aid-cncr16>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bosse T, Nout RA, McAlpine JN, et al. Molecular classification of grade 3 endometrioid endometrial cancers identifies distinct prognostic subgroups. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:561–8. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Broaddus RR, Lynch HT, Chen LM, et al. Pathologic features of endometrial carcinoma associated with HNPCC: a comparison with sporadic endometrial carcinoma. Cancer. 2006;106:87–94. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohn DE, Mutch DG, Herzog TJ, et al. Genotypic and phenotypic progression in endometrial tumorigenesis: determining when defects in DNA mismatch repair and KRAS2 occur. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2001;32:295–301. doi: 10.1002/gcc.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Jong RA, Boerma A, Boezen HM, Mourits MJ, Hollema H, Nijman HW. Loss of HLA class I and mismatch repair protein expression in sporadic endometrioid endometrial carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:1828–36. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirai Y, Banno K, Suzuki M, et al. Molecular epidemiological and mutational analysis of DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes in endometrial cancer patients with HNPCC-associated familial predisposition to cancer. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:1715–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00886.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang HN, Lin MC, Tseng LH, et al. Ovarian and endometrial endometrioid adenocarcinomas have distinct profiles of microsatellite instability, PTEN expression, and ARID1A expression. Histopathology. 2015;66:517–28. doi: 10.1111/his.12543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Black D, Soslow RA, Levine DA, et al. Clinicopathologic significance of defective DNA mismatch repair in endometrial carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1745–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagle CM, O'Mara TA, Tan Y, et al. Endometrial cancer risk and survival by tumor MMR status. J Gynecol Oncol. 2018;29:e39. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2018.29.e39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kommoss S, McConechy MK, Kommoss F, et al. Final validation of the ProMisE molecular classifier for endometrial carcinoma in a large population-based case series. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:1180–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mackay HJ, Gallinger S, Tsao MS, et al. Prognostic value of microsatellite instability (MSI) and PTEN expression in women with endometrial cancer: results from studies of the NCIC Clinical Trials Group (NCIC CTG) Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1365–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maruyama A, Miyamoto S, Saito T, Kondo H, Baba H, Tsukamoto N. Clinicopathologic and familial characteristics of endometrial carcinoma with multiple primary carcinomas in relation to the loss of protein expression of MSH2 and MLH1. Cancer. 2001;91:2056–64. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010601)91:11<2056::aid-cncr1232>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mills AM, Liou S, Ford JM, Berek JS, Pai RK, Longacre TA. Lynch syndrome screening should be considered for all patients with newly diagnosed endometrial cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:1501–9. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Djordjevic B, Barkoh BA, Luthra R, Broaddus RR. Relationship between PTEN, DNA mismatch repair, and tumor histotype in endometrial carcinoma: retained positive expression of PTEN preferentially identifies sporadic non-endometrioid carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:1401–12. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okoye EI, Bruegl AS, Fellman B, Luthra R, Broaddus RR. Defective DNA mismatch repair influences expression of endometrial carcinoma biomarkers. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2016;35:8–15. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0000000000000193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruiz I, Martin-Arruti M, Lopez-Lopez E, Garcia-Orad A. Lack of association between deficient mismatch repair expression and outcome in endometrial carcinomas of the endometrioid type. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;134:20–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shikama A, Minaguchi T, Matsumoto K, et al. Clinicopathologic implications of DNA mismatch repair status in endometrial carcinomas. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;140:226–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stelloo E, Bosse T, Nout RA, et al. Refining prognosis and identifying targetable pathways for high-risk endometrial cancer: a TransPORTEC initiative. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:836–44. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2015.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Talhouk A, Hoang LN, McConechy MK, et al. Molecular classification of endometrial carcinoma on diagnostic specimens is highly concordant with final hysterectomy: earlier prognostic information to guide treatment. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;143:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.07.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Talhouk A, McConechy MK, Leung S, et al. Confirmation of ProMisE: a simple, genomics-based clinical classifier for endometrial cancer. Cancer. 2017;123:802–13. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jumaah AS, Salim MM, Al-Haddad HS, McAllister KA, Yasseen AA. The frequency of POLE-mutation in endometrial carcinoma and prognostic implications: a systemic review and meta-analysis. J Pathol Transl Med. 2020;54:471–9. doi: 10.4132/jptm.2020.07.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:529–36. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC. Robbins and Contran pathologic basis of disease. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders-Elsevier; 2015. pp. 1014–8. [Google Scholar]

- 35.MedCalc . Ostend: MedCalc Software bvba; 2015. Statistical software version 15.8 [Internet] [cited 2020 Dec 10]. Available from: https://www.medcalc.org. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Riley RD, Higgins JP, Deeks JJ. Interpretation of random effects meta-analyses. BMJ. 2011;342:d549. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sterne JA, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JP, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d4002. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryan NA, Glaire MA, Blake D, Cabrera-Dandy M, Evans DG, Crosbie EJ. The proportion of endometrial cancers associated with Lynch syndrome: a systematic review of the literature and metaanalysis. Genet Med. 2019;21:2167–80. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0536-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lorenzi M, Amonkar M, Zhang J, Mehta S, Law KL. Epidemiology of microsatellite instability high (MSI-H) and deficient mismatch repair (dMMR) in solid tumors: a structured literature review. J Oncol. 2020;2020:1807929. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ryan NAJ, Blake D, Cabrera-Dandy M, Glaire MA, Evans DG, Crosbie EJ. The prevalence of Lynch syndrome in women with endometrial cancer: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. 2018;7:121. doi: 10.1186/s13643-018-0792-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jerzak KJ, Duska L, MacKay HJ. Endocrine therapy in endometrial cancer: an old dog with new tricks. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;153:175–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ashley CW, Da Cruz Paula A, Kumar R, et al. Analysis of mutational signatures in primary and metastatic endometrial cancer reveals distinct patterns of DNA repair defects and shifts during tumor progression. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;152:11–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sargent DJ, Marsoni S, Monges G, et al. Defective mismatch repair as a predictive marker for lack of efficacy of fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy in colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3219–26. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fujiyoshi K, Yamamoto G, Takenoya T, et al. Metastatic pattern of stage IV colorectal cancer with high-frequency microsatellite instability as a prognostic factor. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:239–47. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.11313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fountzilas E, Kotoula V, Pentheroudakis G, et al. Prognostic implications of mismatch repair deficiency in patients with nonmetastatic colorectal and endometrial cancer. ESMO Open. 2019;4:e000474. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2018-000474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Copija A, Waniczek D, Witkos A, Walkiewicz K, Nowakowska-Zajdel E. Clinical significance and prognostic relevance of microsatellite instability in sporadic colorectal cancer patients. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:107. doi: 10.3390/ijms18010107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig. S1

Supplementary Fig. S2

Supplementary Fig. S3

Supplementary Fig. S4

Supplementary Fig. S5

Supplementary Fig. S6

Supplementary Fig. S7

Supplementary Fig. S8

Supplementary Fig. S9

Supplementary Fig. S10

Supplementary Fig. S11

Supplementary Fig. S12

Supplementary Fig. S13

Supplementary Fig. S14

Supplementary Fig. S15

Supplementary Fig. S16

References