Abstract

African Americans (AAs) are 20% more likely to develop serious psychological distress compared to Whites but are less likely to use mental health services. The study objective was to evaluate the effectiveness of recruitment strategies to engage AA fathers in a mental health intervention.

Using the community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach, a community-academic partnership (CAP) developed and implemented direct and indirect referral strategies to engage AA fathers in a mental health intervention. Direct referral strategies focused on community partner identification of potentially eligible participants, providing information about the study (i.e., study flyer), and referring potential participants to the study. Indirect referrals included posting flyers in local businesses frequented by AA men, radio advertisements, and social media posts from community organizations.

From January to October 2019, 50 direct and 1388 indirect referrals were documented, yielding 24 participants screened and 15 enrolled. Of all participants screened, 58% were referred through indirect referral, 38% were referred directly by community partners, and 4% of the participants were referred through both direct and indirect referrals. Twenty percent of those exposed to the direct referral methods and 1% of those exposed to the indirect referral methods were enrolled. The indirect referrals accounted for 60% of enrollment, whereas the direct referrals accounted for 33.3% of enrollment.

Collaborating with the community partners to engage hard-to-reach populations in mental health studies allowed for broad dissemination of recruitment methods, but still resulted in low participant accrual. Additional focus on increasing direct referral methods appears to be a fruitful area of CBPR.

Keywords: mental health, African Americans, men, recruitment, community-based participatory research

Recruitment is an essential element of success in translational research studies. It is one of the most challenging steps, with only about 50% of clinical studies being able to achieve their recruitment targets without extensions or delays (Treweek et al., 2018; Walters et al., 2017). Over the last two decades, Cochrane Reviews reported no improvement in the success rates for reaching recruitment targets in clinical trials (Treweek et al., 2010, 2018). Other reviews have reported that less than half of clinical studies reported having achieved their recruitment goals (Charlson & Horwitz, 1984; Foy et al., 2003; Haidich & Ioannidis, 2001; McDonald et al., 2006; Sully et al., 2013). McDonald et al. (2006) identified that, out of 114 clinical trials, 65 needed an extension to achieve their original recruitment goal, while only 38 were able to reach the initial recruitment target. The main challenges investigators encountered included delays in initial timelines and early recruitment problems (Sully et al., 2013; Walters et al., 2017) such as completing contracts with organizational partners and paperwork related to the study, and weak institutional interest in clinical trials, which resulted in a lack of on-site personnel willing to implement the study (Claiborne et al., 2012). About 63% of clinical trials experience early recruitment problems, and 41% of studies described in the review (Sully et al., 2013) had their recruitment delayed.

In addition to the difficulties described by Cochrane and McDonald (Treweek et al., 2010, 2018), recruiting for mental health studies has been shown to be even more difficult. Claiborne et al. (2012) reported that many studies often fail to recruit enough participants, which can result in premature termination of the study (Gul & Ali, 2010). Investigators often encountered multiple concerns related to the patients’ safety, the stigma around mental illness, and demographic differences in mental disorder incidences (Mason et al., 2007; Woodall et al., 2011). Given that the etiologies of some mental illnesses are still not well understood (Liu et al., 2018), some patients and their families can develop skepticism over a new treatment or intervention and are reluctant to engage in clinical trials (Kinon et al., 2011; Rutherford et al., 2014; Walsh et al., 2002). Further, Claiborne and colleagues (2012) reported that patients could be reticent to participate in mental health studies during the consent process because some aspects of the study might appear complex, inconvenient, or irrelevant. Additionally, because of the stigma, patients may prefer to conceal their mental health status (Palmer et al., 2005).

It is well documented that these challenges can jeopardize access to mental health treatment and the likelihood to participate in research, especially for minority groups (Liu et al., 2018). In 2014, it was reported that less than 10% of participants enrolled in clinical research were minorities (Williams et al., 2013). Among those minorities, African Americans’ (AAs) underrepresentation in clinical trials was even more pronounced (Graham et al., 2018). Despite AAs’ underrepresentation in mental health studies, they are disproportionately affected by the burden of mental illnesses. In 2017, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services reported that AAs 18 and older are 40% more likely to report serious psychological distress compared to White non-Hispanics (Department of Health and Human Services, 2019). Suicide was identified as the second leading cause of death for AAs 15–24 years old (Department of Health and Human Services, 2019). Access to mental health services and treatment remains limited for AAs due to the fear of been stigmatized, the culture of perceived self-care sufficiency, and the lack of financial resources (National Alliance on Mental Illness, 2017). It is estimated that only 25% of AAs seek mental health care, compared to 40% of White non-Hispanics (National Alliance on Mental Illness, 2017). In 2017, it was reported that AAs diagnosed with a mental illness were 40% less likely to receive prescription medications when compared with their White counterparts (Department of Health and Human Services, 2019). The challenges of recruitment in clinical trials may sometimes lead to premature termination of some studies or loss in statistical power with the inability to draw relevant conclusions that can benefit the participants (Mahon et al., 2015). Studies will be abandoned before they show their true value and impact, and others may face some ethical problems due to the underpowered trials (Treweek et al., 2018). These missed opportunities and uncertainty may discourage investigators who want to avoid wasting time, funds, and resources (Mahon et al., 2015).

Studies reported multiple cost-effective strategies to improve recruitment in clinical trials (Provencher et al., 2014; Treweek et al., 2018). The Cochrane Reviews reported that sharing information with participants on the expectations of the treatment could increase the number of participants. Also, adding phone calls to the postal invitation is effective in improving recruitment (Treweek et al., 2018). Using targeted messaging can be beneficial for the recruitment of minorities. It is essential to monitor the recruitment process carefully with early detections of the need to add more recruitment settings or modify the inclusion and exclusion criteria in case of delays (Ramsey et al., 2016). Having multiple strategies implemented simultaneously, such as mass mailing, digital strategies, and social media, can also improve the recruitment rate (Treweek et al., 2018).

For minorities, the literature has described that successful recruitment strategies require longstanding trust-building, which will help alleviate the negative beliefs about health-care systems and research (Graham et al., 2018). Referrals from community organizations were reported to have the highest success in recruitment (Ramsey et al., 2016). The community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach has been proposed as an effective way to involve (Chadiha et al., 2011) and recruit minorities. A CBPR study on the mental health of AA men reported that a letter developed by community members in lay language targeted toward AA men led to an increase of more than 10% in the recruitment rate (Spence & Oltmanns, 2011). CBPR is an approach based on building equitable partnerships between the community and the research team (e.g., academia) that build on community strengths (Jones & Wells, 2007; Zimmerman et al., 2015).

Despite these successes, there is a scarcity of mental health studies on AA men, one of the hardest populations to engage in mental health trials. The recruitment strategies that have been reported to be effective with other populations are not necessarily sufficient for AA men (Chadiha et al., 2011). The purpose of this study is to analyze the feasibility of recruitment strategies for AA men into a mental health study (“Master Mind”) designed for AA fathers using the CBPR approach. We hypothesized that an equitable partnership between community partners and academia would yield successful recruitment strategies targeting AA men to participate in a mental health intervention.

Method

Master Mind Study Description

Data were collected from February 2019 to February 2020 as part of a larger trial, Master Mind, that was developed in response to the community need to improve access to mental health care for AA men. This study embedded a mental health intervention into an existing 12-week parenting education program for fathers, which provided parenting and co-parenting skills, linked fathers to community-based resources, and provided opportunities for positive interactions with their children. The main study objectives were (1) to examine the feasibility of implementing a mental health intervention using individual and group cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), and (2) to assess the mental health status and daily functioning of fathers participating in the intervention.

Eligible participants were fathers who self-identified as AA, were at least 19 years and older, resided in the study area, and had a mild mental health diagnosis (e.g., adjustment disorder). We focused on mild mental health diagnoses because they are more common and to prevent future severe mental illness diagnoses. The sessions were held once a week and composed of 1-hr parenting education curriculum followed by 1-hr group CBT intervention. Table 1 displays the topic description covered each week within each category. The study was conducted over a period of 12 months, with a total of three cohorts. The participants read through the written consent form with assistance from a study team member who answered any questions that arose. Once the participants’ questions were answered and agreed to participate, they signed the consent form, in which a copy of the signed consent was given to them. For cohorts 1 and 2, data were collected from study participants at the beginning and end of the 12-week intervention to determine the referral source, receive recommendations about other recruitment sites, and suggested strategies for subsequent cohorts (cohort 3). Demographic characteristics were also collected at baseline in each cohort. The study was approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) (#092-18-EP).

Table 1.

Intervention Weekly Topic Descriptions.

| Theme | Week | Contents | Duration (Hours) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personal responsibility | 1 | Parenting: Identify unique characteristics of parenting and how to best negotiate successful co-parenting relationships. | 2 |

| 2 | The child in you, exploring adverse childhood experiences: Obtain better understanding of impact life have on a man’s role as provider, father, husband/partner, community advocate, leader, and protector. | 2 | |

| 3 | Male sexuality: Owning your own stuff: Examine existing perceptions of sexuality, health risks and consequences associated with at-risk sexual behavior, myths of unprotected sex prevention methods, and overall men’s health. | 2 | |

| Responsibility for your child | 4 | Financial fitness: Learn and apply various techniques of managing basic personal finances, balancing child support payment, and importance of credit and budgeting. | 2 |

| 5 | Child abuse and neglect: Learn what happens when a child is taken from custodial parent, what constitutes child abuse and neglect, short- and long-term effect of child abuse, and status of a 2-offender. | 2 | |

| 6 | Every child deserves your support: Participate in an interactive discussion about intent and purpose of child support, legal and moral obligations of fathers, learn about Nebraska child support guidelines and calculations, and how to request child support modifications. | 2 | |

| Responsibility to your family and community | 7 | Know your rights: Develop a parenting plan, importance of negotiating a parenting plan, and how to utilize plan. | 2 |

| 8 | Communication: Examine the understanding of communication between sexes and identify strategies to identify opportunities to improve overall communication. | 2 | |

| 9 | Domestic violence: Learn warning signs of abuse relationships, examine impact of emotional and physical abuse. | 2 | |

| 10 | Anger management: Examine anger and what it means in the context of parenting and co-parenting. | 2 | |

| 11 | What it is to be a man: Examine manhood based upon race, economics, age, opportunity, family values; create a profile of manhood to guide decision-making. | 2 | |

| 12 | Graduation | 1 |

Community–Academic Partnership (CAP)

Master Mind was a CAP study that employed key principles of CBPR, which have been reported to be effective in recruiting underrepresented minorities (Chadiha et al., 2011). This approach has ten core principles which include: (1) recognizing the community as a unit of identity, (2) building on the strengths and resources of the community, (3) facilitating collaborative and equal partnerships, (4) promoting co-learning among research partners, (5) integrating and achieving a balance between research and action that mutually benefits both the researchers and the community, (6) emphasizing the relevance of community-defined public health problems, (7) employing a cyclical and iterative process to develop and maintain community/research partnerships, (8) disseminating knowledge gained from the CBPR project to and by all involved partners, (9) requiring long-term commitment on the part of all partners, and (10) addressing social inequalities and health disparities (Israel et al., 2017). The approach requires long-term trust-building with community partners (Graham et al., 2018). In this study, a CAP was developed between a Midwestern university medical center and a federally qualified health center. The goal of this manuscript was to report on targeted recruitment strategies that were relatable and culturally appropriate by using the CBPR key principle of shared leadership. The CAP was composed of staff and academic researchers who work or live in the community. The team met weekly to discuss and develop the study design, recruitment, implementation challenges, and dissemination strategies. The partners engaged in equitable and shared leadership and decision-making whenever changes were necessary to the study design and implementation procedures.

Procedure

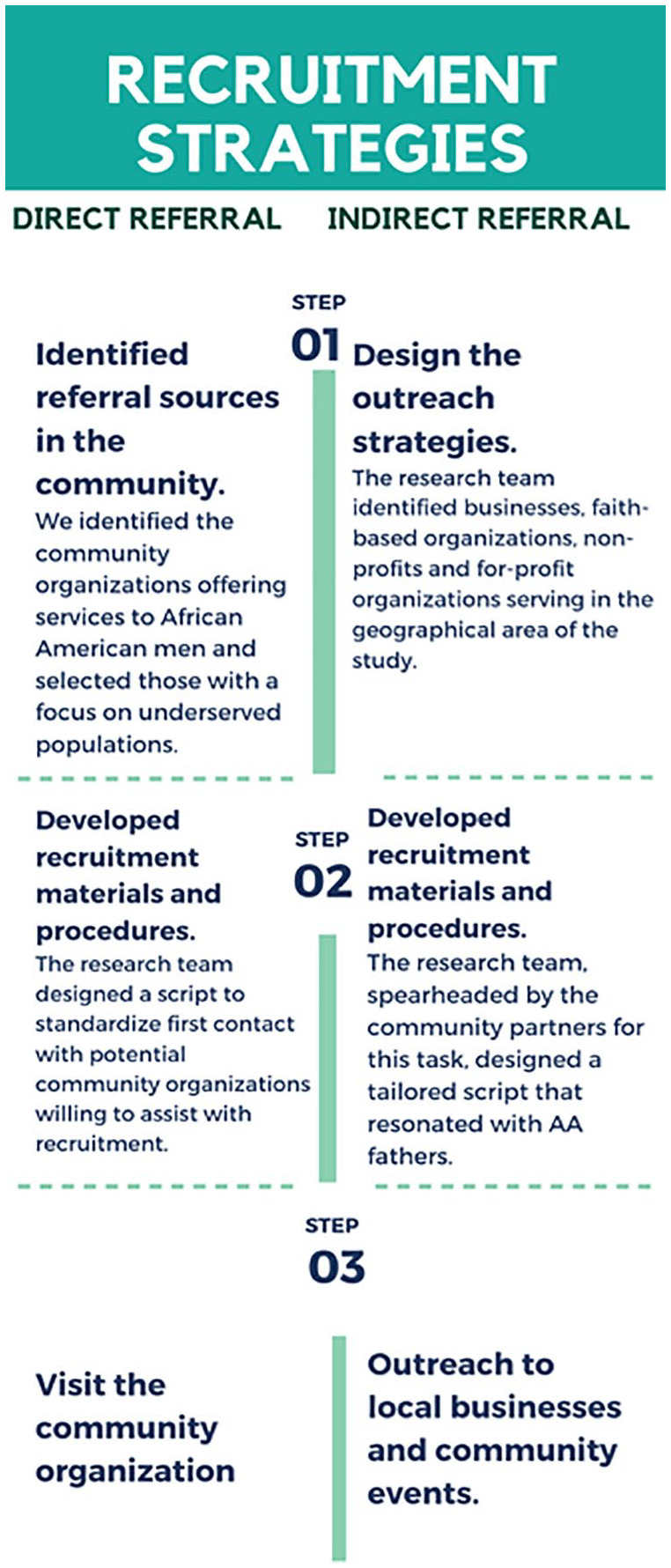

The primary study outcome was to determine the number of AA fathers screened and the number of AA fathers enrolled in the study. Recruitment strategies were collapsed into two overall types: direct referral and indirect referral. Direct referral was defined as a referral coming from community organizations who agreed to assist with recruitment. The community partners referred potential participants based on the inclusion criteria and provided them with information about the study (i.e., study flyer) including the benefits of participation. An indirect referral was defined as outreach (e.g., posting flyers in local businesses frequented by AA men) and media (e.g., radio station mentions, websites posts, and social media posts from community organizations) distributed in the community. Over 10 months, we completed specific recruitment steps (Figure 1) for both direct and indirect referral simultaneously.

Figure 1.

Recruitment strategy for the Master Mind study.

Direct Referral

Step 1: Identified Referral Sources in the Community

Following the second principle of CBPR (building on the strengths and resources of the community) (Chadiha et al., 2011), the CAP identified the community organizations offering services to AA men and selected those with a focus on underserved populations.

Step 2: Developed Recruitment Materials and Procedures

The CAP team designed a script to standardize first contact with potential community organizations willing to assist with recruitment. The script explained the purpose of contacting them, the study description, and how the selected organization can contribute to the recruitment process. In addition, a Frequently Ask Questions (FAQ) sheet was created to facilitate understanding of the study and respond to any common questions and concerns from community organizations or residents during the recruitment process. Lastly, we developed a recruitment database that was used in Step 3. We collected information about the direct referrals such as organization name, address, type of organization, the contact information of the appointed person, dates of visits, number of flyers distributed by the researcher per visit, number of flyers distributed by community partner, number of referrals, and additional comments.

Step 3: Visit the Community Organization

Once a community organization agreed to be a direct referral, the research coordinator added their organization to our recruitment database. The recruitment coordinator planned monthly visits and/or phone calls to receive recruitment updates (e.g., using the recruitment database) and ensured the community organization had a continued commitment to the study recruitment. For the first visit, the research coordinator instructed the community organization’s appointed contact person on the inclusion criteria and how to identify potential participants. The appointed person was given a short script to approach the potential participants and 10–30 flyers. The research coordinator sent a follow-up email after the first visit with details on the information needed for the database and the electronic version of the flyer. The appointed person documented the number of flyers distributed, the number of participants referred to the study, and challenges experienced in recruiting participants. After the first visit, the research coordinator followed up monthly with community organizations through emails, phone calls, or site visits on a regular basis or as needed until recruitment ended. These follow-up discussions consisted of collecting data on the number of flyers distributed, the number of referrals sent to the study, the willingness to continue the partnership, and potential recruitment challenges that need to be addressed. Any potential recruitment challenges were discussed at the weekly CAP team meetings, and a solution was provided to the community organizations. Additional flyers were given to the appointed contact person per their request.

Indirect Referral

Step 1: Design the Outreach Strategies

The CAP team identified businesses, faith-based organizations, non-profits, and for-profit organizations serving in the geographical area of the study. Intensive outreach in the community started at least 6 weeks prior to each cohort and ended the first week of the cohort. Outreach was continued during the cohorts with the intention of recruiting, screening, and enrolling fathers for the subsequent cohort. This process was repeated throughout the 10-month period of recruitment. Data from the first two cohorts were collected from study participants before and after the 12-week intervention to inquire about referral sources and recommendations about other recruitment sites or strategies.

Step 2: Developed Recruitment Materials and Procedures

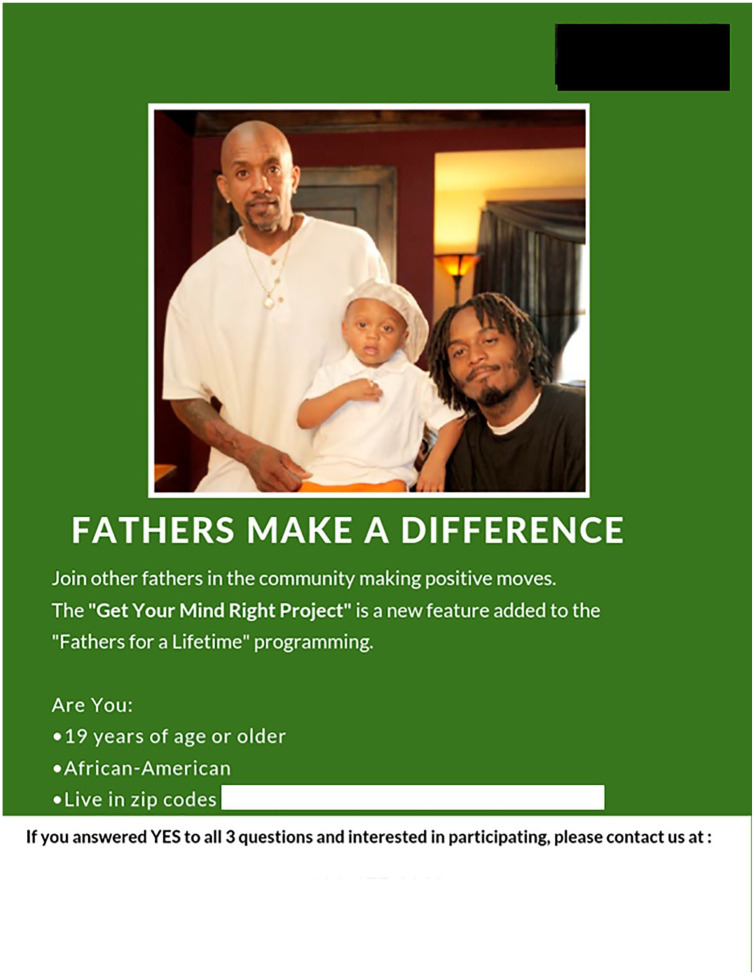

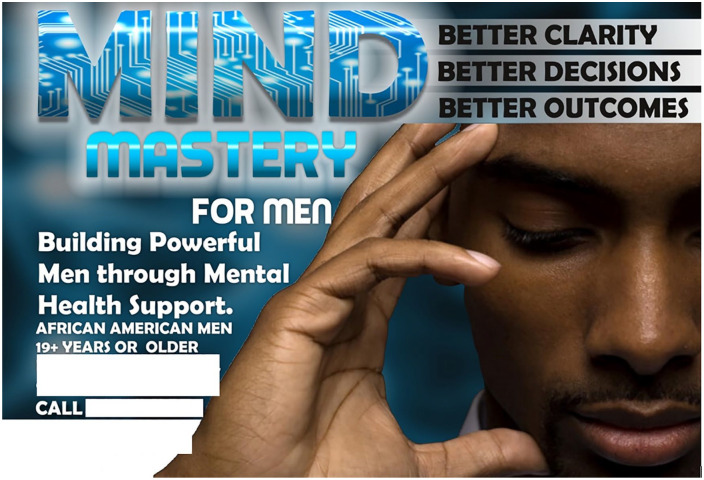

The CAP team, spearheaded by the community partners, designed a tailored script that resonated with AA fathers. The brief script was written using lay terms. It briefly explained the study, common challenges for AA fathers, and benefits of study participation. In addition, the research coordinator developed the original recruitment flyer (Figure 2). After unsuccessful attempts at recruitment, community members were engaged to review recruitment flyer and provide suggestions for changes. The CAP team partnered with a local community organizer who revised the study flyer based on feedback from AA men who lived in the geographical area of the study (Figure 3). Lastly, the CAP team created media messages for community organizations with a social media presence and for our respective CAP websites and social media platforms (e.g., Facebook). Community organizations that participated in direct and indirect referrals were asked to post the social media messages on their social media profiles and pages. The messages contained information about the study and contact information for questions, screening, and enrollment.

Figure 2.

Master Mind initial flyer.

Figure 3.

Revamped study flyer with community inputs.

Step 3: Outreach to Local Businesses and Community Events

The research coordinator and other CAP team members visited local businesses and community events to distribute flyers and promote the study. The CAP team also identified any interested individuals fitting the inclusion criteria or who might know potential participants in his or her social network. The CAP team provided short presentations with more background and rationale, further promoting the study as well as increasing indirect referral sources.

Analytic Plan

Descriptive statistics (e.g., mean, median, mode) were used to summarize the participants’ demographic characteristics and identify the reach of recruitment strategies. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare the median ratio of screened versus exposed and enrolled versus exposed between the direct and indirect referral. Community organizations and potential partners involved in the recruitment process were identified during weekly meetings of the community academic partnership (Chadiha et al., 2011), and qualitative data were gathered through field notes and interaction with community residents and representatives. We collected data on how the CAP related to the appeal of the recruitment strategies and perceptions of program implementation. A p value <.05 was considered statistically significant. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 26.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2019. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) was used to analyze the data.

Results

CBPR Approach, Community Collaboration

The community residents were excited to have a mental health program available in the community despite some reluctance due to mental health stigma and the fear of being seen in a clinic facility. However, community residents reported that the first promotional flyer (Figure 2) was unappealing. The community partners revamped the study flyer (Figure 3), which led to the community residents having a higher interest in the study. The seventh principle of CBPR is to employ a cyclical and iterative process to develop and maintain community/research partnerships (Chadiha et al., 2011). This principle contributed to having promotional materials that resonated more with the community and attracted more AA men to the study.

A total of 24 participants that identified as AA men were screened. Among the eligible participants, 62.5% (n = 15) were enrolled in the study. The mean age was 30 (19–53) years old. Out of the 15 participants enrolled, five (58.3%) had at least a high school diploma. Most of the participants were single (8, 66.7%), with an annual income of less than $20,000 (15, 100%). Of all the participants enrolled, half of the participants were employed (seven out of 14, 50%). The average number of people per household was 2 (range: 1–5).

Over the 10-month recruitment period, a total of 1438 flyers (electronic and hard copies) were distributed. The CAP team had eight direct referral sources (50 flyers distributed) and 91 indirect referral sources (1388). Table 2 gives a description of indirect referral sources that contributed to the recruitment efforts. Approximately 535 (38.5%) of the indirect referral sources came from community events (e.g., health fairs, community baby shower events, end of the year events) and 194 (14%) from community organizations such as fraternity organizations, social welfare organizations such as the Salvation Army, and food pantries. Additionally, 216 (15.6%) from local businesses such as convenience stores, 114 (8.2%) from barbershops, and 75 (5.4%) from grocery stores (5.4%) contributed to the indirect referrals.

Table 2.

Indirect Referral Sources.

| N | Percentage (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hard copies | Auto shop | 33 | 2.4 |

| Bar | 3 | 0.2 | |

| Barber shop | 114 | 8.2 | |

| Beauty shop | 10 | 0.7 | |

| Book store | 45 | 3.2 | |

| Church | 24 | 1.7 | |

| Clothes store | 10 | 0.7 | |

| Coffee shop | 6 | 0.4 | |

| Convenience store | 216 | 15.6 | |

| Community events | 535 | 38.5 | |

| Grocery stores | 75 | 5.4 | |

| Organizations | 194 | 14.0 | |

| Posted in neighborhood | 13 | 0.9 | |

| Public library | 22 | 1.6 | |

| Shelters (homeless) | 22 | 1.6 | |

| Other shops | 17 | 1.2 | |

| Soul food | 13 | 0.9 | |

| Supermarket | 8 | 0.6 | |

| Electronic copies | Social media clicks (community organization websites, Facebook, and Twitter pages) | 48 | 3.5 |

| Radio station | 3 | 0.2 | |

| Total | 1388 | 100 |

A total of 1438 potential participants were exposed to both direct and indirect referrals (Table 3). For the first cohort, 430 (96.4%) people were exposed to indirect referral sources, and 16 (3.6%) were exposed to direct referral sources. For cohorts 2 and 3, respectively, 570 (96.1%) and 388 (97.2%) people were exposed to the indirect referral sources, while 23 (3.9%) and 11 (2.8%) were exposed to the direct referral sources. Of all participants screened (24), nine (37.5%) were referred through direct referrals, 14 (58.3 %) through indirect referral sources, and one (4.2%) of the participants were referred through both direct and indirect sources. Fifteen of the 24 participants (62.5%) screened were enrolled in the study. The indirect referral efforts generated 14 participants screened, and nine enrolled (60% of enrollment), whereas the direct referral generated nine participants screened and five enrolled (33.3% of enrollment). Only one (6.7%) was referred via both sources. The ratios of screening versus exposure were 0.2 for the direct referral and 0.01 for the indirect referral. This means 20% of participants exposed to the direct referral were enrolled while only 1% of participants exposed to the indirect referral were enrolled in the study. There was a statistically significant difference between the direct and indirect referral on the number of participants exposed to the recruitment (Chi square = 6.01, p = .05, df = 2). However, there we no significant differences between the two types of referrals when comparing of the number of participants screened (Chi square = 4.03, p = .18, df = 2) and the number of participants enrolled (Chi square = 4.03, p = .18, df = 2).

Table 3.

Number of Participants Screened and Enrolled per Cohort by Type of Referral Source.

| Cohort | Total Number of Participants | Direct Referral (%) | Indirect Referral (%) | Direct and Indirect Referral (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Exposed | 446 | 16 | 430 | |

| Screened | 8 | 5 (62.5) | 2 (25) | 1 (12.5) | |

| Enrolled | 5 | 3 (60) | 1 (20) | 1 (20) | |

| 2 | Exposed | 593 | 23 | 570 | |

| Screened | 9 | 3 (33.3) | 6 (66.7) | 0 | |

| Enrolled | 6 | 1 (16.7) | 5 (83.3) | 0 | |

| 3 | Exposed | 399 | 11 | 388 | |

| Screened | 7 | 1 (14.3) | 6 (85.7) | 0 | |

| Enrolled | 4 | 1 (25) | 3 (75) | 0 | |

| Total | Exposed | 1438 | 50 | 1388 | |

| Screened | 24 | 9 (37.5) | 14 (58.3) | 1 (4.2) | |

| Enrolled | 15 | 5 (33.3) | 9 (60) | 1 (6.7) |

Discussion

The purpose of our study was to report on the process and feasibility of recruitment strategies for AA fathers to enroll in a mental health intervention, using the CBPR approach. Limited studies exist that explore recruitment strategies for AA men in mental health research (Bryant et al., 2014). This study aimed to fill this gap by exploring strategies to recruit AA men. A CBPR approach was used to engage communities throughout the study and to help create targeted messages that are effective at recruiting AA men for mental health studies (Coleman, 2013; Spence & Oltmanns, 2011); as a result, more AA men were interested in the study. The findings suggest that indirect referrals were the most effective to recruit a larger number of participants (60% of enrolled participants), but proportionally was considerably less effective (1% of those exposed to recruitment materials).

When considered in the context of two previous studies (Bryant et al., 2014; Spence & Oltmanns, 2011) that attempted to accrue AA men in mental health studies, our results suggest that a mix of direct and indirect methods may be necessary. For example, in 2014, Bryant et al. used indirect referrals such as distributing and posting flyers in local community clinics, businesses, churches, and events. After 9 months of recruitment, the research team decided to cease all recruitment efforts because they could not accrue participants. Similar to Bryant et al., our recruitment was initially expected to take 3–4 months and extended to 10 months. While we did not achieve the number of participants originally planned for the pilot study, the addition of direct methods contributed 40% of the study participants indicating that a mix of both indirect and direct methods improved the overall number of participants accrued.

A second generalization of our study is the need to use an iterative approach and engage community partners in the development of recruitment materials early in a project. Previous research on the recruitment of AA men in mental health intervention research reported that targeted messages for AA men that are culturally relevant yielded to an increase of AA men interested in participating (Spence & Oltmanns, 2011). A CAP that included community representatives and experts in psychology and AA studies shifted from traditional recruitment materials and developed a letter to AA men and study materials that included culturally sensitive messages with pictures of the lab members showing the diversity of the research team. The shift doubled the number of AA men expressing interest in participating in the study (Spence & Oltmanns, 2011). Similarly, we initiated recruitment with materials that were developed by research team members of the CAP to reduce the burden on community partners with a similar low accrual. Iterative development of relevant recruitment materials with community members helped to spark the interest in the study despite the reluctance related to mental health stigma.

Our results are also consistent with a study on recruitment strategies for mental health of hard-to-reach populations, which reported that outreach strategies (indirect referrals), such as social media (Facebook), were more effective than direct referrals from health-care professionals to accrue a larger number of participants (Kayrouz et al., 2016). The study focused on Arab immigrants rather than AAs. Given the differences in underlying cultures, but the relative success of indirect referral strategies, this suggests that these findings may generalize to other racial and ethnic groups. General recommendations on the recruitment of minorities in research studies encourage the use of CBPR (Chadiha et al., 2011; Graham et al., 2018; Lightfoote et al., 2014). As we were recognizing the uniqueness of a midwestern AA community (CBPR principle 1), we built a CAP with shared leadership (CBPR principle 3) where the community partners had the lead in various aspects of the recruitment process. It was a learning process for both the community and the research team. The expertise from the community helped us design better recruitment materials such as the culturally relevant script and the revamped flyer (CBPR principles 2, 4, and 5) that were useful in increasing participant interest of the study. The use of CBPR helped us design and implement culturally sensitive recruitment strategies for AA men which have been reported to be effective in previous studies on minorities (Areán et al., 2003; Lightfoote et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2018) and to address trust barriers by working with the community to provide culturally matched resources and partners.

Limitations

Although this study is an attempt to add to the scarcity of literature on recruitment of AA men in mental health research, there are several study limitations. First, this is a feasibility study with a relatively low sample size and a focus on AA fathers, which limit the generalizability of the findings. Therefore, we cannot guarantee the effectiveness of the strategies used in other minority communities or to AA men in general, though the approach does seem promising. However, this study provides valuable insight to the potential effectiveness of using CBPR to develop recruitment strategies while adjusting and working with communities to clarify messaging and incorporate the cultural strength of the community when exploring the access to mental health research and services for AA men. Additionally, the numerator (screened) is not as important as the denominator (enrolled) for our recruitment strategies. More people enrolled through indirect referrals, but the direct referrals required less promotional materials. The third limitation is related to the overlap between the direct and indirect referrals. Both referrals were offered throughout the recruitment period with difficulty to draw a clear distinction on which type of referral motivated the participants’ decision to contact the research team without being exposed to the other strategy. Despite this limitation, the research team was able to collect the self-reported referral type that the participants were exposed to before enrolling in the study. Finally, cost-effectiveness analysis was not performed of both recruitment strategies which limit the capacity to recommend the strategies with the least financial burden.

Conclusion

Our study findings are an addition to the scientific knowledge on the recruitment of hard-to-reach populations for clinical research. This study highlights the importance of using a CBPR approach in the design and implementation of recruitment strategies. It is also important to use both direct and indirect referrals sources to increase the chances of enrolling more participants. Future studies should explore the interdependence of both strategies in mental health research and analyze the cost effectiveness of each recruitment type.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our community partners, residents, and study participants for their commitment and support of this project. We would also like to thank Leo Louis II, Executive Director of the Malcolm X Memorial Foundation, for his consulting on marketing our study in the community of interest.

Footnotes

Credits: All authors participated in the material preparation, implementation, and data collection. Data analysis was performed by Tatiana Tchouankam and Keyonna M. King. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Tatiana Tchouankam and modified by Paul Estabrooks and Keyonna M. King. All authors commented on modified version of the manuscript, reviewed, and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences through the Great Plains IDeA-CTR [grant number 1U54GM115458].

ORCID iDs: Tatiana Tchouankam  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8511-2519

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8511-2519

Roland Thorpe  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4448-4997

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4448-4997

Keyonna M. King  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1951-8734

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1951-8734

Ethics: The study was approved by the University of Nebraska Medical Center Institutional Review Board (IRB) (#092-18-EP).

References

- Areán P. A., Alvidrez J., Nery R., Estes C., Linkins K. (2003). Recruitment and retention of older minorities in mental health services research. The Gerontologist, 43(1), 36–44. 10.1093/geront/43.1.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant K., Wicks M. N., Willis N. (2014). Recruitment of older African American males for depression research: Lessons learned. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 28(1), 17–20. 10.1016/j.apnu.2013.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadiha L. A., Washington O. G., Lichtenberg P. A., Green C. R., Daniels K. L., Jackson J. S. (2011). Building a registry of research volunteers among older urban African Americans: Recruitment processes and outcomes from a community-based partnership. The Gerontologist, 51(suppl_1), S106–S115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson M. E., Horwitz R. I. (1984). Applying results of randomised trials to clinical practice: Impact of losses before randomisation. British Medical Journal, 289(6454), 1281–1284. 10.1136/bmj.289.6454.1281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claiborne A. B., English R. A., Weisfeld V. (2012). Public engagement and clinical trials: New models and disruptive technologies: Workshop summary. National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman D. (2013). Immigration, population and ethnicity: The UK in international perspective. Migration observatory briefing. COMPAS, University of Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services. (2019, September 25). Mental and behavioral health - African Americans. Health, United States, 2017: With special feature on mortality. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=24

- Foy R., Parry J., Duggan A., Delaney B., Wilson S., Lewin-Van Den Broek N. T., Myres P. (2003). How evidence based are recruitment strategies to randomized controlled trials in primary care? Experience from seven studies. Family Practice, 20(1), 83–92. 10.1093/fampra/20.1.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham L. F., Scott L., Lopeyok E., Douglas H., Gubrium A., Buchanan D. (2018). Outreach strategies to recruit low-income African American men to participate in health promotion programs and research: Lessons from the men of color health awareness (MOCHA) project. American Journal of Men’s Health, 12(5), 1307–1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gul R. B., Ali P. A. (2010). Clinical trials: The challenge of recruitment and retention of participants. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19(1–2), 227–233. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03041.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidich A. B., Ioannidis J. P. (2001). Patterns of patient enrollment in randomized controlled trials. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 54(9), 877–883. 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00353-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel B. A., Schulz A. J., Parker E. A., Becker A. B., Allen A. J., Guzman J. R., Lichtenstein R. (2017). Critical issues in developing and following CBPR principles. Community-based participatory research for health: Advancing social and health equity (pp. 31–46). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Jones L., Wells K. (2007). Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. Jama, 297(4), 407–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayrouz R., Dear B. F., Karin E., Titov N. (2016). Facebook as an effective recruitment strategy for mental health research of hard to reach populations. Internet Interventions, 4, 1–10. 10.1016/j.invent.2016.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinon B. J., Potts A. J., Watson S. B. (2011). Placebo response in clinical trials with schizophrenia patients. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 24(2), 107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lightfoote J. B., Fielding J. R., Deville C., Gunderman R. B., Morgan G. N., Pandharipande P. V., Macura K. J. (2014). Improving diversity, inclusion, and representation in radiology and radiation oncology part 2: Challenges and recommendations. Journal of the American College of Radiology, 11(8), 764–770. 10.1016/j.jacr.2014.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Pencheon E., Hunter R. M., Moncrieff J., Freemantle N. (2018). Recruitment and retention strategies in mental health trials–a systematic review. PloS One, 13(8), e0203127. 10.1371/journal.pone.0203127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon E., Roberts J., Furlong P., Uhlenbrauck G., Bull J. (2015). Barriers to clinical trial recruitment and possible solutions: A stakeholder survey. https://www.appliedclinicaltrialsonline.com/view/barriers-clinical-trial-recruitment-and-possible-solutions-stakeholder-survey [Google Scholar]

- Mason V., Shaw A., Wiles N., Mulligan J., Peters T., Sharp D., Lewis G. (2007). GPs’ experiences of primary care mental health research: A qualitative study of the barriers to recruitment. Family Practice, 24(5), 518–525. 10.1093/fampra/cmm047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald A. M., Knight R. C., Campbell M. K., Entwistle V. A., Grant A. M., Cook J. A., Snowdon C. (2006). What influences recruitment to randomised controlled trials? A review of trials funded by two UK funding agencies. Trials, 7, 9. 10.1186/1745-6215-7-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance on Mental Illness. (2017, n.d.). African American mental health. https://www.nami.org/Your-Journey/Identity-and-Cultural-Dimensions/Black-African-American

- Palmer B. A., Pankratz V. S., Bostwick J. M. (2005). The lifetime risk of suicide in schizophrenia: A reexamination. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(3), 247–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provencher V., Mortenson W. B., Tanguay-Garneau L., Bélanger K., Dagenais M. (2014). Challenges and strategies pertaining to recruitment and retention of frail elderly in research studies: A systematic review. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 59(1), 18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey T. M., Snyder J. K., Lovato L. C., Roumie C. L., Glasser S. P., Cosgrove N. M., Still C. H. (2016). Recruitment strategies and challenges in a large intervention trial: Systolic blood pressure intervention trial. Clinical Trials, 13(3), 319–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford B. R., Pott E., Tandler J. M., Wall M. M., Roose S. P., Lieberman J. A. (2014). Placebo response in antipsychotic clinical trials: A meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(12), 1409–1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence C. T., Oltmanns T. F. (2011). Recruitment of African American men: Overcoming challenges for an epidemiological study of personality and health. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17(4), 377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sully B. G., Julious S. A., Nicholl J. (2013). A reinvestigation of recruitment to randomised, controlled, multicenter trials: A review of trials funded by two UK funding agencies. Trials, 14, 166. 10.1186/1745-6215-14-166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treweek S., Mitchell E., Pitkethly M., Cook J., Kjeldstrom M., Taskila T., Jones R. (2010). Strategies to improve recruitment to randomised controlled trials. Cochrane Database Systematic Review, (1), Mr000013. 10.1002/14651858.MR000013.pub4 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Treweek S., Pitkethly M., Cook J., Fraser C., Mitchell E., Sullivan F., Gardner H. (2018). Strategies to improve recruitment to randomised trials. Cochrane Database Systematic Review, 2, Mr000013. 10.1002/14651858.MR000013.pub6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh B. T., Seidman S. N., Sysko R., Gould M. (2002). Placebo response in studies of major depression: Variable, substantial, and growing. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 287(14), 1840–1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters S. J., Bonacho Dos Anjos Henriques-Cadby I., Bortolami O., Flight L., Hind D., Jacques R. M., Julious S. A. (2017). Recruitment and retention of participants in randomised controlled trials: A review of trials funded and published by the United Kingdom Health Technology Assessment Programme. BMJ Open, 7(3), e015276. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams M. T., Beckmann-Mendez D. A., Turkheimer E. (2013). Cultural barriers to African American participation in anxiety disorders research. Journal of the National Medical Association, 105(1), 33–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodall A., Howard L., Morgan C. (2011). Barriers to participation in mental health research: Findings from the Genetics and Psychosis (GAP) study. International Review of Psychiatry, 23(1), 31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman E. B., Woolf S. H., Haley A. (2015). Understanding the relationship between education and health: A review of the evidence and an examination of community perspectives. In Kaplan R. M., Spittel M. L., David D. H. (Eds.), Population health: Behavioral and social science insights (pp. 347–384). Rockville. [Google Scholar]