Dear Editor

COVID-19, caused by SARS-CoV-2, is affecting many people worldwide. Huge numbers of people are being killed due to the virus. Although many patients are recovering from COVID-19, it is important to keep in mind that there may be possible complications after convalescence, including unfavorable non-pulmonary effects. One of these complications is avascular necrosis (AVN), which may lead to negative outcomes and bone collapse if missed. AVN was seen frequently in SARS and may also be common in COVID-19 infection. It should be kept in mind that the threat of AVN still remains with patients recovered from COVID-19 infection, like SARS.

Some guidelines suggest corticosteroid use for various conditions of COVID-19.1 , 2 According to WHO, although corticosteroids are not advised to be given routinely, they are indicated in some occasions such as COPD or asthma exacerbation or septic shock.2 The Surviving Sepsis Campaign suggests (in the form of a weak recommendation) systemic corticosteroids use in patients on a ventilator who have Acute respiratory distress syndrome.1 On the other hand, to date, dexamethasone is the first drug found to be of great help in saving lives of COVID-19 patients. According to the RECOVERY clinical trial, which was one of the biggest studies about COVID-19 treatments, this medication decreased risk of death in hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19 who are on ventilator or receive oxygen, by 20%.3 Apart from steroids, the effects of the virus itself on the human body is another issue.

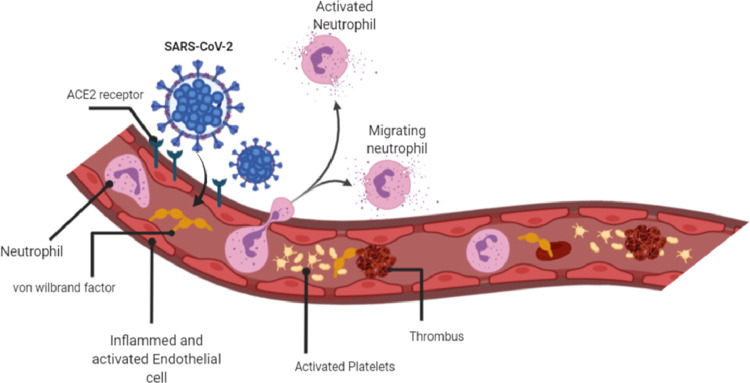

AVN may also happen due to microvascular thrombosis. Thrombi development could be a result of endothelial cell damage (Figure 1 ).4 AVN may occur distal to the site of arterial obstruction.4 Veyre et al. wrote a case report presenting a 24-year-old man with non-severe COVID-19 who had femoral arterial thrombosis.5 The patient was found to have a common femoral artery thrombosis with extension in the first third of profunda and superficial femoral arteries accompanied by thrombosis of tibial posterior and popliteal artery. Fortunately, the patient recovered by anticoagulation and antiaggregant therapy as well as thrombectomy. The only possible etiology was explained to be non-severe COVID-19.5 It is known that SARS-CoV-2 enters host cells via angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protein, which is expressed by endothelial cells as well as lungs and leads to vascular lesions via coagulopathy and inflammatory syndrome.6

Figure 1.

Effects of SARS-CoV-2 on endothelial cells and thrombus formation. Created with BioRender.com.

Endothelial activation and changes in endothelial cells were reported in severe COVID-19 infection. Escher et al. observed a man with COVID-19 infection who had a massive elevation of von Willebrand factor, which is presumed to arise from endothelial changes.7 Varga et al. have reported multiorgan vascular injury in endothelial cell and endotheliitis of COVID-19 patients in postmortem studies.8 Ackermann et al. found severe endothelial cell damage, widespread thrombosis and microangiopathy in lungs of COVID-19 patients.9 The inflammatory effects of cytokines induced by SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19 is another factor contributing to endothelial cell injury and the following thrombosis.10

Currently, in the absence of large data of patient follow-up, early diagnosis of AVN is important, because the consequent bone collapse may be prevented. Thus, it is recommended that large joint pain after COVID-19 should be taken seriously, in order to not miss AVN.

Footnotes

Financial support: None.

Declaration of Competing Interest: Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YM. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Intensive Care Med. 2020:1–34. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06022-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected. accessed on 21-11-2020. Availablefrom: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/clinical-management-of-severe-acute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected.

- 3.Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19 — Preliminary Report. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kerachian MA, Harvey EJ, Cournoyer D, Chow TYK, Séguin C. Avascular Necrosis of the Femoral Head: Vascular Hypotheses. Endothelium. 2006;13(4):237–244. doi: 10.1080/10623320600904211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veyre F, Poulain-Veyre C, Esparcieux A. Femoral Arterial Thrombosis in a Young Adult after Nonsevere COVID-19. Ann Vasc Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2020.07.013. S0890-5096(20)30604-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sardu C, Gambardella J, Morelli MB, Wang X, Marfella R, Santulli G. Hypertension, Thrombosis, Kidney Failure, and Diabetes: Is COVID-19 an Endothelial Disease? A Comprehensive Evaluation of Clinical and Basic Evidence. J Clin Med. 2020;9(5):1417. doi: 10.3390/jcm9051417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Escher R, Breakey N, Lämmle B. Severe COVID-19 infection associated with endothelial activation. Thromb Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet North Am Ed. 2020;395(10234):1417–1418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ackermann M, Verleden SE, Kuehnel M. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huertas A, Montani D, Savale L. Eur Respiratory Soc; 2020. Endothelial cell dysfunction: a major player in SARS-CoV-2 infection (COVID-19)? [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]