Abstract

Recurrent waves of spreading depolarization (SD) occur in brain injury and are thought to affect outcomes. What triggers SD in intracerebral hemorrhage is poorly understood. We employed intrinsic optical signaling, laser speckle flowmetry, and electrocorticography to elucidate the mechanisms triggering SD in a collagenase model of intracortical hemorrhage in mice. Hematoma growth, SD occurrence, and cortical blood flow changes were tracked. During early hemorrhage (0–4 h), 17 out of 38 mice developed SDs, which always originated from the hematoma. No SD was detected at late time points (8–52 h). Neither hematoma size, nor peri-hematoma perfusion were associated with SD occurrence. Further, arguing against ischemia as a trigger factor, normobaric hyperoxia did not inhibit SD occurrence. Instead, SDs always occurred during periods of rapid hematoma growth, which was two-fold faster immediately preceding an SD compared with the peak growth rates in animals that did not develop any SDs. Induced hypertension accelerated hematoma growth and resulted in a four-fold increase in SD occurrence compared with normotensive animals. Altogether, our data suggest that spontaneous SDs in this intracortical hemorrhage model are triggered by the mechanical distortion of tissue by rapidly growing hematomas.

Keywords: Cerebral amyloid angiopathy, electrocorticography, intracerebral hemorrhage, laser speckle imaging, spreading depolarization

Introduction

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) accounts for approximately 20% of all strokes1 with a case fatality rate of 40% after one month.2 Mortality has not changed over time within the past few decades, and there is no effective treatment.2,3 Therefore, it is critical to better understand the pathophysiology of injury progression in this devastating disease to improve clinical outcomes.

Spreading depolarizations (SD) are intense depolarization waves akin to spreading depression. Recurrent SD waves erupt in apparently spontaneous fashion in injured brain in both experimental animals and humans regardless of the mode of injury.4,5 Once triggered, SDs slowly propagate with a speed of millimeters per minute throughout the injured brain far into the surrounding healthy tissue like a tsunami wave, imposing a tremendous metabolic burden, triggering large changes in blood flow, inducing neuroinflammation, and opening the blood–brain barrier.6–8 As such, SDs are believed to increase the severity of stroke-related injury.

The occurrence of SDs has been shown in swine models of ICH as well as in patients suffering from spontaneous ICH.9–16 However, how and why SDs are triggered in ICH are poorly understood. Common triggers include anoxic, hypoglycemic or ischemic failure of Na+/K+-ATPase, direct exposure to chemical depolarizing agents (e.g. high extracellular K+ or glutamate), or mechanical distortion of brain tissue.6,17–19 Blood breakdown products have been hypothesized as a potential trigger. Here, we undertook a comprehensive investigation of the natural history of SD occurrence and examined potential mechanisms triggering SDs in a mouse model of ICH. Our data show that hematoma growth rate, but not hematoma size or tissue oxygenation, is associated with SD occurrence, implicating mechanical pressure due to the growing hematoma as the main trigger for SDs in acute ICH.

Methods

Experimental animals

Experiments were approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee following the NIH Guide for Use and Care of Laboratory Animals, and data are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines. A total of 62 male and 4 female CD1 mice (2.6 months (IQR, 2.3-4.3 months); 36.1g (IQR, 34.2-38.1g); Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA) were allowed for food and tap water ad libitum. In control cohorts, male and female mice did not differ. Therefore, data of both sexes were pooled.

General surgical preparation

Mice were anesthetized using isoflurane (2.5% induction, 1–1.25% maintenance in 69% N2/30% O2) and allowed to breathe spontaneously. Rectal temperature was maintained at 37°C (IQR, 36.8-37.2°C) via a thermostatic heating pad (TC-1000 Temperature Controller, CWE, Ardmore, PA, USA). Blood pressure and heart rate were continuously monitored via a femoral artery catheter (PowerLab; ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, MO, USA). Animals were placed in a stereotaxic frame, local anesthetic (lidocaine gel 2%) applied, skull exposed by midline scalp incision, and connective tissue removed. Mineral oil was applied to maintain skull translucency. After obtaining baseline intrinsic optical signal (IOS) and laser speckle contrast images, two burr holes were drilled over the right hemisphere, one for electrophysiological recordings at a remote frontal site (1.5 mm anterior and 0.5 mm lateral from bregma), and one for ICH induction in the parietal cortex (2 mm posterior and 3 mm lateral from bregma). Experimental setup is shown in Figure 1(a). After surgical preparation, mice were allowed to stabilize for 20 min. A glass capillary microelectrode filled with 0.9% NaCl (tip diameter ∼10 µm) was carefully placed at a cortical depth of 300 µm through the anterior burr hole to record the electrocorticogram (ECoG) and extracellular steady (DC) potential (EX1; Dagan Corporation, Minneapolis, MN, USA; PowerLab; ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA). Arterial pH, pCO2, and pO2 were measured in 25 µl blood samples at 2 h and 4 h. Animals were sacrificed at the end of the experiment to quantify the hematoma volume (Figure 1(a)).

Figure 1.

Experimental design. (a) Experimental setup including the femoral artery catheter to monitor systemic physiology, the camera for intrinsic optical signal imaging (IOS), a second camera and a near infrared laser diode for laser speckle flowmetry (LSF). Horizontal line shows typical experimental timeline. Starting 0, 8, 24, or 48 h after collagenase injection, electrophysiology (ECoG,DC), arterial blood pressure (BP), IOS, and LSF were continuously recorded for 4 h. Representative electrophysiological (DC) and blood pressure (BP) tracings, and IOS and LSF images are shown. A typical slow negative extracellular potential shift of the SD wave is shown on the DC tracing recorded by a glass capillary microelectrode (e; 1.5 mm anterior and 0.5 mm lateral from bregma) visible on the IOS image along with the intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) around collagenase injection site (2 mm posterior and 3 mm lateral from bregma). All images are obtained through intact skull. LSF image shows CBF changes relative to baseline (%) as shown in the color bar. The field of view is similar to IOS. Representative 1-mm coronal sections were prepared at the end of the recordings to calculate ICH volume. (b) Hemorrhage volume measured using coronal sections correlates with hemoglobin content measured later in tissue homogenates (Spearman r=0.56, p<0.001; left panel). (c) The dorsal area of ICH prior to sacrifice (as seen in IOS) showed a tight and linear correlation with the ICH volume calculated post-mortem (Spearman r = 0.92, p<0.001; right panel). Each dot represents a single animal.

Intracortical hemorrhage induction

In pilot experiments, we tested various collagenase concentrations, volumes, injection rates, and depths to determine the optimal parameters to induce various sizes of intracortical hemorrhage. A 10 µl syringe (34-gauge, Small Hub RN Needle, point style 4, Hamilton Company, Reno, NV, USA) was filled with bacterial collagenase VII-S (0.2–0.6 U/µl; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The needle was lowered into the cortex via the posterior burr hole to a depth of 0.5 mm and 0.2 µl collagenase was injected at a rate of 0.67 µl/min over 3 min using a manual injection pump. To examine the propensity for developing SD across a range of ICH volumes, we varied the collagenase dose (0.04–0.12 IU). After collagenase injection the needle was left in place for 5 min to prevent backflow and then slowly removed. Three sham-operated mice received saline injection and did not develop any ICH during 4 h of monitoring identical to collagenase-injected mice (not shown).

Imaging

Intrinsic optical signal imaging and laser speckle flowmetry (LSF) were carried out simultaneously with cortical electrophysiological recordings to detect ICH growth, SD occurrence, and their impact on cerebral blood flow (CBF) (Figure 1(a)). Briefly, a camera (MU300, AmScope, Irvine, CA, USA) was positioned over the dorsal skull to image every 4 s the ICH growth that was conspicuously visible through the skull under diffuse white light illumination. The green channel of the same images was used to detect IOS changes associated with SDs, as previously described.20 Spatiotemporal changes in CBF were imaged using LSF as described previously.21,22 A near infrared laser diode (785 nm) with a penetration depth of ∼500 µm was used to diffusely illuminate intact skull and a CCD camera (CoolSnap cf, 1392 × 1040 pixels; Photometrics, Tucson, AZ) was positioned above the head. Raw speckle images were acquired at 15 Hz and processed using a sliding grid of 7 × 7 pixels to calculate speckle contrast, a measure of speckle visibility related to the velocity of scattering particles. Ten consecutive images were averaged to improve signal-to-noise ratio. Speckle contrast images were then transformed into images of correlation time values. The correlation time expresses the decay time of the light intensity autocorrelation function and is linearly and inversely proportional to the mean blood velocity.23 To monitor relative CBF changes over the time course of the experiment, baseline images were taken prior to any intervention. By calculating the ratio of a baseline image of correlation time values to subsequent images, the percentage of baseline CBF was computed and expressed as relative CBF image. Laser speckle perfusion images were taken every 3.5 s. Six animals were excluded from CBF analysis due to poor skull translucence.

ICH volume

At the end of the experiment, mice were transcardially perfused with 30 ml of phosphate-buffered saline under deep isoflurane anesthesia (5%) to clear intravascular blood. Brains were removed and cut into 1 mm coronal sections (Figure 1(a)). Hematoma volume was calculated using sections photographed under standardized conditions by integrating the hemorrhage areas manually outlined on each section along the anteroposterior axis. Tissue was then homogenized for photometric hemoglobin assay, as described previously.24

Experimental protocols in ICH experiments

Experimental timeline is shown in Figure 1(a). In early ICH (n = 51), electrophysiology, IOS, LSF, and blood pressure (BP) were continuously recorded starting immediately after collagenase injection for 4 h. A separate cohort of mice (n = 9) were monitored for SDs during the late phase of ICH (8–52 h). To minimize morbidity during the survival period after collagenase injection in this group, femoral artery was not catheterized, and scalp was sutured and local analgesic (Lidocaine gel 2%) applied after collagenase injection. Mice were allowed to recover from anesthesia, returned to their home cages for 8, 24, or 48 h, and then re-anesthetized for femoral artery catheterization, SD monitoring, and hematoma volume measurement as above. Hyperoxia (n = 8) was induced in a separate set of animals by switching inspiration air to 100% O2 15 min after collagenase injection; these animals were followed for the full 4 h as above, along with their time controls (n = 8). Hypertension (n = 10) was induced by a single intraperitoneal injection of phenylephrine (10 mg/kg) at the onset of ICH growth phase (49 min (IQR, 30-58 min) after collagenase injection) and animals were sacrificed 30 min after the last observed SD. The final ICH volume calculated by integrating the hematoma areas on coronal sections correlated with the hemoglobin content subsequently measured in tissue homogenates (Spearman r = 0.60, p < 0.001; Figure 1(b)). Moreover, the dorsal area of ICH prior to sacrifice showed a tight linear correlation with the ICH volume calculated post-mortem (Spearman r = 0.91 p < 0.001; Figure 1(c)), thus allowing us to use the ICH area to calculate ICH growth over time.

Focal cerebral ischemia

In a separate group of mice (n = 6), after general surgical preparation as above, instead of ICH, distal middle cerebral artery was occluded using a microvascular clip through a temporal burr hole as previously described.25 Mice were then monitored for 4 h as in ICH experiments above to detect SDs. After the experiment, animals were transcardially perfused with 30 ml of phosphate-buffered saline under deep isoflurane anesthesia (5%), brains were removed and snap frozen in −40°C isopentane, and 20 µm-thick cryosections were collected every 1 mm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Infarct areas on each section were integrated to calculate infarct volume.

Statistical analysis

The operator was blinded during surgery and hemorrhage induction. Because SDs were clearly discernible during imaging, blinding was not possible for image analysis although CBF analysis was automated using a Matlab script. Hematoma volume calculation using photometric hemoglobin assay was performed in a blinded fashion. Data in text are expressed as median along with interquartile range. Data in figures are expressed as whisker (full range) and box (interquartile range) plots (horizontal line, median; +, mean) or mean and 95% confidence interval. In the absence of prior experience, sample sizes in ICH experiments were chosen empirically to detect a 33% difference between means and a presumed standard deviation of 25% of the mean (a = 0.05, b = 0.10). Statistical tests were carried out using Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA), and indicated for each dataset along with sample sizes in the text or the figure legends. Spearman correlation, χ2-test, Mann–Whitney test, unpaired t-test, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons, two-way ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak multiple comparison, multiple linear regression, and two-way repeated-measures ANOVA were performed when appropriate. Data were tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Results

Cortical hematomas emerged approximately 20 min after collagenase injection and expanded at a variable rate. By the end of the 4-h recordings, hematoma expansion usually slowed down, approaching a plateau (Figure 2(a), Supplementary Movie 1). Consistent with this, hematoma volumes at 8, 24, or 48 h did not differ from those at 4 h after collagenase injection and did not change during these late recordings (Figure 2(b)).

Figure 2.

Spreading depolarizations occur during early but not late stages of intracortical hemorrhage. (a) Representative intrinsic optical signal (IOS) images (every 30 min), continuous electrophysiological recordings (ECoG and DC), and the coronal section at the end of the experiment from two animals in the early stage of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) (0–4 h). The first animal (top) has a slow growing, small hematoma, and did not develop any spreading depolarization (SD). The second animal (bottom) developed a large hematoma within 90 min. Two SDs occurred during this rapid growth phase (arrowheads). (b) Representative data from an animal studied at a later stage (48–52 h) of ICH. Despite the large hematoma, there was no change in hematoma size and no SD. (c) Time of SD occurrence during early stage of ICH in animals that developed at least one SD. Each line represents one animal and each circle represents one SD. Most SDs emerged between 30 and 120 min after collagenase injection. Animals with no SD are not shown. (d) SD frequency and ICH volume are shown for early and late stages. There was no SD detected during late stages of ICH (p=0.020 vs. early stage; Mann–Whitney test) despite nearly identical hematoma volumes (p=0.99 vs. early stage; Mann–Whitney test).

Only a subset of mice (17 out of 38; 45%) developed SDs during early ICH, which invariably and conspicuously originated from the region of ICH detected on IOS (Supplementary Movie 2) and LSF. These were confirmed by the characteristic slow negative extracellular potential shift when SD propagated to the remote electrophysiological recording site (Figure 2(a), arrowheads). Majority of SDs occurred between 30 and 120 min after collagenase injection, sometimes in couplets 8–19 min apart (Figure 2(c)). In contrast, we did not detect any SD in late ICH (Figure 2(b) and (d); n = 9; p = 0.012 vs. early stage, χ2) despite comparable hematoma volumes (7.3 mm3 (IQR, 3.6–15.6 mm3) vs. 6.4 mm3 (IQR, 5.1–15.5 mm3), respectively; p = 0.99; Mann–Whitney test; Figure 2(d)). These data suggested that neither the hematoma volume nor the blood constituents or breakdown products significantly influence SD occurrence in ICH.

Because ICH did not grow at all during the late stages (peak growth rate 0.0 mm3/10 min (IQR, 0.0–0.0 mm3/10 min) vs. 1.2 mm3/10 min (IQR, 0.6-2.8 mm3/10 min), late vs. early phase, n = 9 and 38, respectively; p < 0.001, Mann–Whitney test), we hypothesized that SD occurrence may relate to the hematoma growth rate. To examine this, we plotted the hematoma volume over time in animals that developed an SD and compared this to animals that did not (n = 17 and 21, respectively; Figure 3(a)). We found that the first SD always emerged when hematoma volume was still relatively small and nearly identical to the final hematoma volume in animals that did not develop an SD (4.8 mm3 (IQR, 3.6–6.9 mm3) vs. 4.0 mm3 (IQR, 1.9–6.8 mm3), respectively; p = 0.59, unpaired t-test; Figure 3(a), blue whisker-box plot). This confirmed our earlier conclusion that the amount of blood per se did not predict SD occurrence.

Figure 3.

Intracortical hemorrhage volume, growth rate, and occurrence of spreading depolarizations. (a) Volume of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) shown as a function of time in animals with spreading depolarization (SD) (left panel) and without spreading depolarization (right panel). Each line represents one animal. Filled circles mark the first SD, unfilled circles mark subsequent SDs. Average hematoma volumes at the time of first SD and at the end of the experiment are shown as whisker-box plots to the right of each time course graph. The mean time of first SD occurrence (t1st SD) is shown as dotted line on all graphs as a reference point. Hematoma volumes at the time of first SD (blue whisker-box plot) were nearly identical to the final hematoma volumes in animals that never developed an SD (gray whisker-box plot in no SD group; p=0.59, unpaired t-test). (b) Average ICH growth per 10-min intervals (see inset) is shown before and after the first SD in each animal that developed one, and the average of first SD time points (tSD) in animals that did not develop any SD. ICH growth accelerated and peaked right before an SD (left panel), whereas no acceleration was observed in animals that did not develop any SD (right panel). Moreover, ICH growth during the 10 min preceding the first SD was significantly higher than the ICH growth at an equivalent time point, as well as the peak growth rate at any time point, in animals not developing an SD (p<0.001 or p=0.014, respectively, Mann–Whitney test).

Instead, we noticed that in animals that developed an SD hematoma growth followed an early steep rise and SDs usually emerged during this rapid growth phase (Supplementary Movie 2). To test this statistically, we calculated the slope of the ICH growth curve preceding SDs (Figure 3(b) inset) and compared this to the peak slope in animals that did not develop an SD, as well as to the slope at 65 min, which was the average time point when SD occurred after collagenase injection. We found that the rate of ICH growth during the 10 min preceding, an SD (1.3 mm3/10 min (IQR, 0.9–2.4 mm3/10 min)) was significantly higher than both the peak growth rate at any time during the 4-h imaging (0.7 mm3/10 min (IQR, 0.3–1.3 mm3/10 min); p = 0.014, Mann–Whitney test) as well as the growth rate at 65 min (tSD, 0.2 mm3/10 min (IQR, 0.1–0.7 mm3/10 min); p < 0.001, Mann–Whitney test) in animals that did not develop an SD. These data indicated that hematoma growth rate is associated with SD occurrence in acute ICH.

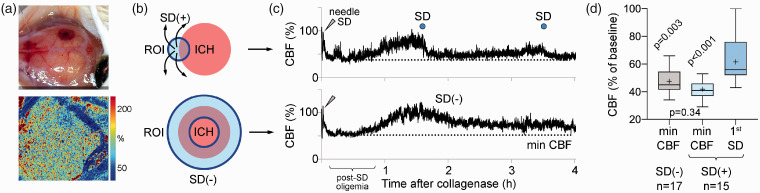

We considered possible mechanisms by which ICH growth might trigger SDs. First, rupture of multiple microvessels could lead to cortical ischemia, a well-known trigger for SD. To test this, we measured the CBF changes around the growing ICH (Figure 4(a)) by placing a region of interest (ROI, 0.8 mm diameter) at the origin of SD and compared this to average CBF in equivalent vicinity of hematoma in experiments without an SD (0.8 mm-thick ring ROI; Figure 4(b)). SDs were detected by the characteristic CBF changes.6 Although the needle insertion for collagenase injection inevitably caused an SD in all experiments, and consequently a post-SD oligemia that reduced CBF to ∼40–50% of baseline for ∼45 min, CBF never declined below this level (Figure 4(c)). Indeed, CBF recorded at the origin of an SD right before the SD emerged (56.0% (IQR, 52.0–76.0%)) was significantly higher than the minimum CBF ever reached throughout the experiments in both the group that developed SDs and the group that did not (41.0% (IQR, 37.0–46.0%) and 45.0% (IQR, 41.5-54.5%), p < 0.001 and p = 0.003, n = 15 and 17, respectively, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons; Figure 4(d)). CBF at the onset of first SD was never at levels known to trigger anoxic SD (<30% of baseline), arguing against ischemia as the immediate trigger for SDs after ICH in this mouse model. Importantly, blood on dorsal cortical surface did not interfere with the LSF signal unless it formed a thick clot (Supplementary Figure 1), the effect of which was to diminish the CBF signal, and therefore, did not affect our conclusions. To further strengthen our conclusion, we employed normobaric hyperoxia, which is known to suppress ischemic SDs.26 We hypothesized that if ischemia played a role in triggering SDs after ICH then normobaric hyperoxia should suppress SD occurrence. Switching inspired air to 100% O2 increased arterial pO2 by almost 4-fold (128 mmHg (IQR, 115–134 mmHg) vs. 482 mmHg (IQR, 429–486 mmHg), control and hyperoxia groups, respectively; p < 0.001, Mann–Whitney test), without altering other systemic physiological parameters (Supplementary Table 1). Normobaric hyperoxia did not affect the peak ICH growth rate (Figure 5(a)), the lowest CBF reached during the recording, the CBF level immediately preceding the SD (Figure 5(b)), the fraction of animals developing an SD or the frequency of SDs during acute ICH (Figure 5(c)), confirming our conclusion that ischemia is not a trigger for SDs in ICH.

Figure 4.

Cerebral blood flow and spreading depolarization occurrence. (a) Representative cortical hemorrhage in the right hemisphere (top) and simultaneous laser speckle flowmetry (LSF) showing relative cerebral blood flow (CBF) imaged through intact skull (bottom). CBF within the ICH is mildly reduced, while rest of the cortex shows normal CBF. (b) Region of interest (ROI, blue shaded) placement at the hemorrhage site is shown for CBF calculation. In animals that developed a spreading depolarization (SD) (top), a circular ROI (0.8 mm diameter) was placed where SD originated from to plot CBF changes in that ROI throughout the 4-h experiment. In animals that did not develop any SD (bottom), a ring ROI (0.8 mm-thick) was placed at the average distance of all SD origins to the center of ICH to capture the CBF in an equivalent perimeter of ICH. (c) Representative CBF tracings are shown from such ROIs in animals with or without SD (bottom and top, respectively). In both cases, CBF decreased to approximately 50% of baseline after the initial SD caused by needle insertion for collagenase injection (0 min), which is typical for post-SD oligemia in mice. An SD (top tracing, blue circle) emerged 100 min after collagenase when CBF was approximately 90% of baseline at its origin. A second SD occurred later around 210 min. The minimum CBF in each tracing is marked by a dotted line. (d) Minimum CBF in experiments that did not show an SD and minimum CBF as well as CBF at the onset of first spontaneous SD in animals that developed one are shown. Average CBF when and where SD originated was above 60% of baseline and significantly higher than the minimum CBF levels reached in either group (p<0.001 and p = 0.003 vs. 1st SD; one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test).

Figure 5.

Effects of normobaric hyperoxia on spreading depolarization occurrence. (a) Normobaric hyperoxia (NBO) was induced 10 min after collagenase injection and compared with normoxic controls (n=8 each). NBO did not affect final hemorrhage volume (p=0.410 vs. control, unpaired t-test) or peak hemorrhage growth rate (p=0.554, Mann–Whitney test). (b) NBO did not affect the minimum cerebral blood flow (CBF) reached during the experiment or the CBF immediately preceding the first spreading depolarization (SD) (p=0.986 and p=0.459, respectively; Mann–Whitney test). (c) NBO did not affect the fraction of animals developing an SD (p=0.590, χ2) or the frequency of SDs (p = 0.991, Mann–Whitney test).

An alternative mechanism by which rapid ICH growth could trigger an SD is physical distortion of tissue by the expanding hematoma. To test this hypothesis, we accelerated the hematoma growth by pharmacologically induced hypertension (n = 10). Intraperitoneal phenylephrine administered to coincide with the typical growth phase of ICH, elevated arterial pressure by as much as 70% within 10 min (Figure 6(a)), and slightly increased CBF around the hematoma (∼16%; p > 0.05; data not shown). This accelerated the ICH growth such that the average hematoma volume reached over 240 min in the control group (7.3 mm3 (IQR, 3.6–15.6 mm3), n = 38) was reached within 40 min after phenylephrine administration (7.5 mm3 (IQR, 5.0–16.2 mm3); p = 0.907, Mann–Whitney test; Figure 6(b)). Indeed, peak ICH growth rate was almost tripled compared with controls (3.7 mm3/10 min (IQR, 2.3–7.7 mm3/10 min) vs. 1.3 mm3/10 min (IQR, 0.8–2.8 mm3/10 min); p = 0.003, Mann–Whitney test; Figure 6(b)), which significantly increased the SD frequency compared with normotensive controls (0.6 SDs/h (IQR, 0.0–1.0 SDs/h) vs. 0.0 SDs/h (IQR, 0.0–0.5 SDs/h), n = 10 and 38, respectively; p = 0.05, Mann–Whitney test, Figure 6(c)). However, we noted that still only 60% of hypertensive animals developed SDs, which was only slightly higher than the controls (45%; p = 0.390, χ2; Figure 6(c)), and the peak ICH growth rate appeared to show a wider spread in the hypertensive group (Figure 6(b)). We, therefore, dichotomized the animals based on SD occurrence and found significantly higher ICH growth rates in animals that developed an SD in both controls and hypertensive animals (p < 0.001 SD vs. No SD, two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak multiple comparison; Figure 6(d)). In other words, hypertension led to higher SD occurrence only when it succeeded in accelerating hematoma growth. Moreover, among the animals that developed an SD, faster ICH growth rates in the hypertensive group corresponded to higher SD frequencies (0.9 SDs/h (IQR, 0.6–2.0 SDs/h) vs. 0.5 SDs/h (IQR, 0.5–0.5 SDs/h) in hypertensive and control group, respectively; p < 0.001, Mann–Whitney test). To further dissociate the contribution of ICH growth rate and final ICH volume, we performed a multiple linear regression (independent variables: peak ICH growth rate, final ICH volume; dependent variable: SD frequency) using the entire cohort (n = 48) and found that SD frequency correlated with the peak ICH growth rate (β = 0.122, p = 0.010) but not the final ICH volume (β = 0.008, p = 0.578). These data indicated rapid increase in hematoma volume as the main determinant of SD occurrence, supporting mechanical distortion of the tissue as the likely trigger.

Figure 6.

Accelerating hematoma growth triggers spreading depolarization in intracortical hemorrhage. (a) Intraperitoneal administration of phenylephrine 45 min after collagenase injection increased blood pressure (BP) by 70% compared to baseline within 15 min. (b) The surge in BP accelerated hematoma growth so that the volume of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) in the normotensive group after 240 min was reached in the hypertensive group within only 40 min after phenylephrine injection (p=0.945, Mann–Whitney test; left panel). Peak ICH growth rate was more than doubled in hypertensive animals (HTN) compared with normotensive controls (p=0.003, Mann–Whitney test), with a wider range of values (right panel). (c) Induced hypertension increased spreading depolarization (SD) frequency by fourfold compared with controls (p=0.050, Mann–Whitney test; left panel). In contrast, the percentage of animals developing SDs only increased from 45% to 60% (p=0.39, χ2; right panel). (d) We next dichotomized controls and hypertensive animals based on SD occurrence. In both groups, animals that developed an SD showed significantly higher ICH growth rates, than animals not developing an SD (p<0.001, two-way ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak multiple comparison). Moreover, hypertensive animals that developed SDs had faster ICH growth rates than controls that developed SDs (p<0.001, two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak multiple comparison), explaining the overall higher SD frequencies in the hypertensive group.

An additional mechanism that could lead to SD during ICH was exposure of brain tissue to plasma concentrations of glutamate (45 µM) and aspartate (5 µM). We examined this possibility by intracortical injection of saline with 50 or 100 µM glutamate (n= 5 each), or 45 µM glutamate with 5 µM aspartate (n = 6). We adjusted the injection rate to mimic the peak ICH growth rate in our study that triggered SDs (0.2 µl/min), and continued it for 20 min, which is the longest period such ICH growth rate was sustained in all the experiments. We did not observe a single SD during glutamate ± aspartate infusion in any of these animals.

Lastly, we noted that while ICH did trigger SDs, the overall SD frequency appeared to be lower than what has been reported in focal cerebral ischemia in mice, despite comparable lesion volumes and locations.25–29 We, therefore, sought to directly test this using a distal middle cerebral artery occlusion model in a separate set of animals (n = 6; Figure 7). All but one ischemic animal developed at least one SD during the 4-h monitoring period (83% of mice). Compared with ICH matching in size and location (12.4 mm3 (IQR, 6.6–17.4 mm3); n = 27), cortical ischemic lesions (13.8 mm3 (IQR, 7.2–17.2 mm3) resulted in more than 2-fold higher SD frequencies (0.4 SDs/h (IQR, 0.0–0.5 SDs/h) vs. 0.9 SDs/h (IQR, 0.4–2.0 SDs/h), respectively; p = 0.039; Mann–Whitney test). These data suggested that the propensity of primary ICH to trigger SDs is significantly lower than primary focal ischemic infarcts.

Figure 7.

Propensity of primary intracortical hemorrhage and primary focal ischemic infarcts to develop spreading depolarizations. Top panel shows a representative intracortical hemorrhage on 1-mm coronal section 4 h after injection of collagenase (left) and a representative focal ischemic lesion (arrowheads) on H&E-stained coronal section 4 h after distal middle cerebral artery occlusion (right). Despite nearly identical location and lesion volume (middle panel), ischemic lesions triggered more than twice the number of spreading depolarizations compared with hemorrhagic lesions (p = 0.039, Mann–Whitney test; bottom panel). For this comparison, we used 27 out of the 38 intracortical hemorrhage animals in control groups studied above with hematoma volumes matching the infarct volumes for a common denominator.

Discussion

Mechanisms triggering SD in the setting of subarachnoid hemorrhage have been examined for over three decades,30,31 although they remain controversial.32–34 Yet, mechanisms triggering SD in the setting of ICH have rarely been investigated. Our data in this cortical ICH model show that hematoma growth rate predicts SD occurrence in acute ICH, suggesting mechanical distortion as the immediate trigger. The data also argue against a contribution by blood breakdown products to SD occurrence in our ICH model, because SD occurrence was independent of absolute hematoma volume and SDs occurred only during acute ICH (0–4 h) and never during the late stages (8–52 h) when blood breakdown is higher.35 Consistent with these, topical application of blood triggers SD only when hemolyzed.34

Mechanical distortion is a well-known trigger for SD.6,17,18 We found that SDs originate from the vicinity of the hematoma during rapid growth. Accelerating growth by hypertension also increased SD occurrence without altering the final hematoma volume. Taken together with the above findings, these data strongly suggest mechanical distortion as the trigger for SDs in this ICH model. Although we did not attempt to measure local pressures in order to avoid invasive instrumentation, mass effect and tissue distortion by expanding hematoma are characteristic of ICH36 and can even shear local arterioles causing secondary hemorrhage.37 Collagenase itself did not directly trigger SD because SDs occurred with a latency of 30 min or more and coincided with rapid hematoma growth. Moreover, perihematomal edema and inflammation occur many hours to days after ICH and are unlikely to have contributed to SD occurrence in our study. Of course, we cannot exclude the presence of a yet unknown blood-borne SD trigger that is present only during rapid hematoma growth and dissipates quickly thereafter.

Focal ischemia, either in the territory of the ruptured artery or by perihematomal pressure,36,38 is another potential SD trigger in ICH. Recurrent SDs occur in virtually all focal ischemic strokes and are triggered when reduced supply or increased demand transiently worsens supply-demand mismatch in moderately ischemic peri-infarct tissue.25 Our data argue against ischemia as a trigger for SDs in ICH because: (a) laser speckle imaging showed that CBF never dropped below levels associated with anoxic depolarization (i.e. <30%) in this ICH model, (b) SDs originated when and where CBF was relatively higher (i.e. >50% of baseline), (c) normobaric hyperoxia, which inhibits SD occurrence only in focal ischemic brain,26,39 did not affect SD occurrence in ICH, and (d) induced hypertension, which does not affect SD occurrence in focal ischemia,40 increased SD occurrence in ICH. The interference in our CBF measurements by the hematoma did not confound our conclusions because, if anything, this would have made the CBF values to appear lower than they actually were.

As an additional modulator, blood glutamate and aspartate could facilitate SD occurrence in ICH. However, they are unlikely to be a direct trigger in acute ICH because cortical exposure to whole blood does not induce SD,41 consistent with relatively low plasma levels (∼50 µM), and hemolysis starts only 24 h after ICH and continues slowly for several days.42–46 Consistent with this, intracortical infusion of glutamate with or without aspartate did not trigger SD.

The time of onset and frequency of SDs in our mouse model matched those in gyrencephalic swine where SDs appeared 20–40 min after collagenase injection,9 suggesting that the phenomenon is not species dependent. This study in swine added heparin in collagenase, used a wide craniectomy and created subcortical seated ICH. Nevertheless, SDs still originated from the hematoma boundary as we show here in mice. In human brain, SDs have only been examined in relatively late stages after ICH, since intracranial recordings were possible only when a craniectomy was needed for hematoma evacuation. Moreover, most cases were deep lobar and basal ganglia ICH. Such recordings show that SDs occur in about two-thirds of patients with large ICH and peak one to two days after ICH onset.12–16 Therefore, in case of massive subcortical ICH, other mechanisms such as perihematomal edema and hypoperfusion may play a role in triggering SDs.15,47 Hematoma evacuation may have altered the pathophysiology as well. Of note, SDs are more frequently observed after ICH secondary to arteriovenous malformations than hypertensive ICH.48 Indeed, transient focal neurological deficits, which often display a spreading pattern reminiscent of migraine aura, are characteristic of cerebral amyloid angiopathy.49,50 As such, at least a subset of transient focal neurological deficits might signify new onset, growing microbleeds.

Our study has limitations. First, we did not measure peri-hematomal tissue pressure directly. This was because any attempt to measure tissue pressure would be invasive and might have influenced the hematoma growth. Therefore, our conclusions are indirect. Second, some hematomas likely leaked into the subarachnoid space, judging by the transcranial appearance and the post-mortem findings. This, however, was most severe at later stages when hematomas were larger, growth slower, and SDs rare. Indeed, subacute recordings showed even larger amounts of subarachnoid blood when not a single SD was observed. Therefore, the amount of subarachnoid blood temporally did not match peak SD occurrence times. Nevertheless, presence of subarachnoid blood may have influenced SD occurrence. Third, LSF may have missed microheterogeneities in tissue perfusion within the ROI. However, the minimum critical volume of depolarization needed to trigger an SD in rodent brain is estimated to be ∼1 mm3,51 and given 10 µm/pixel resolution of our LSF system, any regional hypoperfusion that was not visible on LSF would be unlikely to trigger an SD. Fourth, we do not know whether collagenase-induced ICH stems from arterial or capillary disruption, although literature suggests a mixed effect.52–59 Collagenase injection into the brain parenchyma disrupts multiple microvessels including the capillary bed, and therefore may not be representative of clinical ICH, which is usually due to arteriole rupture and hemorrhage from a single source. Nevertheless, the source of bleeding in this model would not change our conclusions. Lastly, we cannot exclude the possibility of more severe ischemia in human ICH compared with our model. Clinical correlation is limited because measurements during the first few hours of ICH are not typically available from human brain.

In summary, we present experimental data indicating that rapid hematoma growth predicts SD occurrence during early cortical ICH. Data also suggest that mechanisms likely involve mechanical distortion of gray matter by the expanding hematoma and argue against blood breakdown products and ischemia as other potential SD triggers. Whether these SDs impact the outcome of ICH remains to be tested.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jcb-10.1177_0271678X20951993 for Rapid hematoma growth triggers spreading depolarizations in experimental intracortical hemorrhage by Paul Fischer, Kazutaka Sugimoto, David Y Chung, Isra Tamim, Andreia Morais, Tsubasa Takizawa, Tao Qin, Carlos A Gomez, Frieder Schlunk, Matthias Endres, Mohammad A Yaseen, Sava Sakadzic and Cenk Ayata in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Funding: The author(s) disclose receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding was received by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke at the NIH (R01NS102969 to CA), Fondation Leducq (CA, ME), Ellison Foundation (CA), Andrew David Heitman Foundation (CA, DC), DFG under Germany’s Excellence Strategy – EXC – 2049 – 390688087 (ME), Federal Ministry of Education and Research Germany (ME), German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (ME), German Centre for Cardiovascular Research (ME), European Union (ME), Corona Foundation (ME), NIH (R25NS065743, KL2TR002542 and K08NS112601 to DC; R01AA027097 and R00AG042026 to MY), American Heart Association and American Stroke Association (18POST34030369 to DC), Aneurysm and AVM Foundation (DC), Brain Aneurysm Foundation (DC).

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: M.E. reports grants from Bayer and fees paid to the Charité from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Daiichi Sankyo, Amgen, GSK, Sanofi, Covidien, Novartis, Pfizer, all outside the submitted work. The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ contributions: PF and CA designed research; PF, KS, DC, AM, TT, QT, CG, MY and SS performed the experiments; PF, DC, IT, FS, ME and CA analyzed data; PF and CA wrote the manuscript; all authors critically reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content and approved the final manuscript.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iDs

Paul Fischer https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7673-8552

Kazutaka Sugimoto https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7666-2620

David Y Chung https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7149-5851

References

- 1.O'Donnell MJ, Xavier D, Liu L, et al. Risk factors for ischaemic and intracerebral haemorrhagic stroke in 22 countries (the INTERSTROKE study): a case-control study. Lancet 2010; 376: 112–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Asch CJ, Luitse MJ, Rinkel GJ, et al. Incidence, case fatality, and functional outcome of intracerebral haemorrhage over time, according to age, sex, and ethnic origin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol 2010; 9: 167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poon MT, Fonville AF, Al-Shahi Salman R.Long-term prognosis after intracerebral haemorrhage: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014; 85: 660–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartings JA, Shuttleworth CW, Kirov SA, et al. The continuum of spreading depolarizations in acute cortical lesion development: examining Leao's legacy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2017; 37: 1571–1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dreier JP, Fabricius M, Ayata C, et al. Recording, analysis, and interpretation of spreading depolarizations in neurointensive care: review and recommendations of the COSBID research group. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2017; 37: 1595–1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayata C, Lauritzen M.Spreading depression, spreading depolarizations, and the cerebral vasculature. Physiol Rev 2015; 95: 953–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sadeghian H, Lacoste B, Qin T, et al. Spreading depolarizations trigger caveolin-1-dependent endothelial transcytosis. Ann Neurol 2018; 84: 409–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takizawa T, Qin T, Lopes de Morais A, et al. Non-invasively triggered spreading depolarizations induce a rapid pro-inflammatory response in cerebral cortex. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2020; 40: 1117–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mun-Bryce S, Wilkerson AC, Papuashvili N, et al. Recurring episodes of spreading depression are spontaneously elicited by an intracerebral hemorrhage in the swine. Brain Res 2001; 888: 248–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mun-Bryce S, Roberts L, Bartolo A, et al. Transhemispheric depolarizations persist in the intracerebral hemorrhage swine brain following corpus callosal transection. Brain Res 2006; 1073–1074: 481–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orakcioglu B, Uozumi Y, Kentar MM, et al. Evidence of spreading depolarizations in a porcine cortical intracerebral hemorrhage model. Acta Neurochir Suppl 2012; 114: 369–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strong AJ, Fabricius M, Boutelle MG, et al. Spreading and synchronous depressions of cortical activity in acutely injured human brain. Stroke 2002; 33: 2738–2743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fabricius M, Fuhr S, Bhatia R, et al. Cortical spreading depression and peri-infarct depolarization in acutely injured human cerebral cortex. Brain 2006; 129: 778–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schiefecker AJ, Beer R, Pfausler B, et al. Clusters of cortical spreading depolarizations in a patient with intracerebral hemorrhage: a multimodal neuromonitoring study. Neurocrit Care 2015; 22: 293–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helbok R, Schiefecker AJ, Friberg C, et al. Spreading depolarizations in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: association with perihematomal edema progression. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2017; 37: 1871–1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schiefecker AJ, Kofler M, Gaasch M, et al. Brain temperature but not core temperature increases during spreading depolarizations in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2018; 38: 549–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Somjen GG.Mechanisms of spreading depression and hypoxic spreading depression-like depolarization. Physiol Rev 2001; 81: 1065–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dreier JP, Reiffurth C.The stroke-migraine depolarization continuum. Neuron 2015; 86: 902–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ayata C.Pearls and pitfalls in experimental models of spreading depression. Cephalalgia 2013; 33: 604–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung DY, Sugimoto K, Fischer P, et al. Real-time non-invasive in vivo visible light detection of cortical spreading depolarizations in mice. J Neurosci Methods 2018; 309: 143–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dunn AK, Bolay H, Moskowitz MA, et al. Dynamic imaging of cerebral blood flow using laser speckle. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2001; 21: 195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ayata C, Dunn AK, Gursoy OY, et al. Laser speckle flowmetry for the study of cerebrovascular physiology in normal and ischemic mouse cortex. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2004; 24: 744–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Briers JD.Laser Doppler, speckle and related techniques for blood perfusion mapping and imaging. Physiol Meas 2001; 22: R35–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foerch C, Arai K, Jin G, et al. Experimental model of warfarin-associated intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 2008; 39: 3397–3404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.von Bornstadt D, Houben T, Seidel JL, et al. Supply-demand mismatch transients in susceptible peri-infarct hot zones explain the origins of spreading injury depolarizations. Neuron 2015; 85: 1117–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shin HK, Dunn AK, Jones PB, et al. Normobaric hyperoxia improves cerebral blood flow and oxygenation, and inhibits peri-infarct depolarizations in experimental focal ischaemia. Brain 2007; 130: 1631–1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eikermann-Haerter K, Lee JH, Yalcin N, et al. Migraine prophylaxis, ischemic depolarizations, and stroke outcomes in mice. Stroke 2015; 46: 229–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eikermann-Haerter K, Lee JH, Yuzawa I, et al. Migraine mutations increase stroke vulnerability by facilitating ischemic depolarizations. Circulation 2012; 125: 335–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shin HK, Dunn AK, Jones PB, et al. Vasoconstrictive neurovascular coupling during focal ischemic depolarizations. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2006; 26: 1018–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hubschmann OR, Kornhauser D.Cortical cellular response in acute subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg 1980; 52: 456–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dreier JP, Ebert N, Priller J, et al. Products of hemolysis in the subarachnoid space inducing spreading ischemia in the cortex and focal necrosis in rats: a model for delayed ischemic neurological deficits after subarachnoid hemorrhage? J Neurosurg 2000; 93: 658–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hartings JA, York J, Carroll CP, et al. Subarachnoid blood acutely induces spreading depolarizations and early cortical infarction. Brain 2017; 140: 2673–2690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chung DY, Oka F, Ayata C.Spreading depolarizations: a therapeutic target against delayed cerebral ischemia after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Clin Neurophysiol 2016; 33: 196–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oka F, Hoffmann U, Lee JH, et al. Requisite ischemia for spreading depolarization occurrence after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rodents. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2017; 37: 1829–1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dang G, Yang Y, Wu G, et al. Early erythrolysis in the hematoma after experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. Transl Stroke Res 2017; 8: 174–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keep RF, Hua Y, Xi G.Intracerebral haemorrhage: mechanisms of injury and therapeutic targets. Lancet Neurol 2012; 11: 720–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schlunk F, Bohm M, Boulouis G, et al. Secondary bleeding during acute experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 2019; 50: 1210–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elijovich L, Patel PV, Hemphill JC, 3rd. Intracerebral hemorrhage. Semin Neurol 2008; 28: 657–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kudo C, Nozari A, Moskowitz MA, et al. The impact of anesthetics and hyperoxia on cortical spreading depression. Exp Neurol 2008; 212: 201–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shin HK, Nishimura M, Jones PB, et al. Mild induced hypertension improves blood flow and oxygen metabolism in transient focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke 2008; 39: 1548–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oka F, Hoffmann U, Lee JH, et al. Requisite ischemia for spreading depolarization occurrence after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rodents. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2017; 37: 1829–1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xi G, Keep RF, Hoff JT.Mechanisms of brain injury after intracerebral haemorrhage. Lancet Neurol 2006; 5: 53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thiex R, Tsirka SE.Brain edema after intracerebral hemorrhage: mechanisms, treatment options, management strategies, and operative indications. Neurosurg Focus 2007; 22: E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aronowski J, Zhao X.Molecular pathophysiology of cerebral hemorrhage: secondary brain injury. Stroke 2011; 42: 1781–1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wagner KR, Sharp FR, Ardizzone TD, et al. Heme and iron metabolism: role in cerebral hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2003; 23: 629–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qing WG, Dong YQ, Ping TQ, et al. Brain edema after intracerebral hemorrhage in rats: the role of iron overload and aquaporin 4. J Neurosurg 2009; 110: 462–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Herweh C, Juttler E, Schellinger PD, et al. Perfusion CT in hyperacute cerebral hemorrhage within 3 hours after symptom onset: is there an early perihemorrhagic penumbra? J Neuroimaging 2010; 20: 350–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hertle DN, Dreier JP, Woitzik J, et al. Effect of analgesics and sedatives on the occurrence of spreading depolarizations accompanying acute brain injury. Brain 2012; 135: 2390–2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Charidimou A, Peeters A, Fox Z, et al. Spectrum of transient focal neurological episodes in cerebral amyloid angiopathy: multicentre magnetic resonance imaging cohort study and meta-analysis. Stroke 2012; 43: 2324–2330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Charidimou A, Boulouis G, Gurol ME, et al. Emerging concepts in sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Brain 2017; 140: 1829–1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matsuura T, Bures J.The minimum volume of depolarized neural tissue required for triggering cortical spreading depression in rat. Exp Brain Res 1971; 12: 238–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosenberg GA, Mun-Bryce S, Wesley M, et al. Collagenase-induced intracerebral hemorrhage in rats. Stroke 1990; 21: 801–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Manaenko A, Chen H, Zhang JH, et al. Comparison of different preclinical models of intracerebral hemorrhage. Acta Neurochir Suppl 2011; 111: 9–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schlunk F, Greenberg SM.The pathophysiology of intracerebral hemorrhage formation and expansion. Transl Stroke Res 2015; 6: 257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barratt HE, Lanman TA, Carmichael ST.Mouse intracerebral hemorrhage models produce different degrees of initial and delayed damage, axonal sprouting, and recovery. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2014; 34: 1463–1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.MacLellan CL, Silasi G, Poon CC, et al. Intracerebral hemorrhage models in rat: comparing collagenase to blood infusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2008; 28: 516–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.James ML, Warner DS, Laskowitz DT.Preclinical models of intracerebral hemorrhage: a translational perspective. Neurocrit Care 2008; 9: 139–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kirkman MA, Allan SM, Parry-Jones AR.Experimental intracerebral hemorrhage: avoiding pitfalls in translational research. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2011; 31: 2135–2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hemorrhagic Stroke Academia Industry Roundtable P. Basic and translational research in intracerebral hemorrhage: limitations, priorities, and recommendations. Stroke 2018; 49: 1308–1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jcb-10.1177_0271678X20951993 for Rapid hematoma growth triggers spreading depolarizations in experimental intracortical hemorrhage by Paul Fischer, Kazutaka Sugimoto, David Y Chung, Isra Tamim, Andreia Morais, Tsubasa Takizawa, Tao Qin, Carlos A Gomez, Frieder Schlunk, Matthias Endres, Mohammad A Yaseen, Sava Sakadzic and Cenk Ayata in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.