Abstract

Previous observational studies suggest associations between red blood cell (RBC) transfusion and risk for arterial or venous thrombosis. We determined the association between thrombosis and RBC transfusion in hospitalized patients using the Recipient Database from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Recipient Epidemiology and Donor Evaluation Study-III. A thrombotic event was a hospitalization with an arterial or venous thrombosis ICD-9 code and administration of a therapeutic anticoagulant or antiplatelet agent. Patients with history of thrombosis or a thrombosis within 24 hours of admission were excluded. A proportional hazards regression model with time-dependent covariates was calculated. Estimates were adjusted for age, sex, hospital, smoking, medical comorbidities, and surgical procedures. Of 657 412 inpatient admissions, 67 176 (10.2%) received at least one RBC transfusion. Two percent (12927) of patients experienced a thrombosis. Of these, 2587 developed thrombosis after RBC transfusion. In unadjusted analyses, RBC transfusion was associated with an increased thrombosis risk [HR = 1.3 (95% CI 1.23-1.36)]. After adjustment for surgical procedures, age, sex, hospital, and comorbidities, no association between RBC transfusion on risk of venous and arterial thrombosis was found [HR 1.0 (95% CI: 0.96-1.05)]. Thus, RBC transfusion does not appear to be an important risk factor for thrombosis in most hospitalized patients.

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Blood transfusion is one of the most common procedures among hospitalized patients with 12-16 million units of red blood cells (RBC) transfused in the United States annually.1 Exposure to blood from another human is associated with multiple risks, including transfusion reactions, infectious disease transmission, and alloimmunization. Previous observational studies have also suggested an association between red blood cell (RBC) transfusion and an increased risk for arterial and venous thrombosis.2–6 Understanding the potential risks associated with RBC transfusion is essential for appropriate management of patients requiring transfusion.

There are plausible biochemical mechanisms describing how RBC transfusion could increase the risk for thrombosis. The RBCs undergo structural and biochemical changes and hemolysis during storage at 4°C that may promote thrombosis following blood transfusion. After 2 weeks of storage, membrane structural proteins become fragmented and alterations in RBC shape occur, releasing microparticles that promote thrombin generation.7,8 The degree of hemolysis is influenced by age, sex, and ethnicity. Transfusion of free hemoglobin may further promote thrombosis as it scavenges nitric oxide, a potent vasodilator and inhibitor of platelet aggregation.9,10 Lastly, blood viscosity is primarily determined by RBCs, and elevated blood viscosity has been associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular events.11,12

In addition to potential biochemical plausibility, previous epidemiologic studies evaluated the relationship between RBC transfusion and arterial and/or venous thrombosis. A study based on the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database showed a dose-dependent increase in post-operative venous thrombotic events (OR 2.1, 95% CI 2.0-2.3) when combining patients transfused before, during, or after surgery.2 A study of colorectal surgery patients from 2005-2008 using the NSQIP database did not identify transfusion as a risk factor for thrombosis.3 In contrast, a subsequent study of patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer found a dose-dependent association of RBC transfusion with post-operative venous thrombotic events.4 A study using the University Health System Consortium discharge database observed an association between RBC transfusion and venous thrombosis in hospitalized cancer patients was observed (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.5-1.7).5 Other studies have found associations between RBC transfusion and risk for arterial graft thrombosis in patients undergoing lower extremity bypass surgery (OR 2.1 if 1-2 units RBC transfused and OR 4.8 if ≥3 units transfused),6 and risk for thrombosis in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage (OR 2.4, 95% CI 1.2-4.6).13 Although there is some variation in published studies, most have found that RBC transfusion increases risk for thrombosis.

The findings associating RBC transfusion with thrombotic events have limitations that warrant further investigation because the data available for analysis and methodological challenges may have influenced study outcomes. Several analyses did not account for the temporal sequence of thrombosis and transfusion to ensure that transfusion occurred prior to the thrombotic event.2,5 Logistic regression modeling does not account for the time elapsed between risk and outcome, and does not account for censoring (ie, when patients’ follow-up is terminated for some reason, such as hospital discharge). Several of the available databases also have limited information about comorbidities influencing thrombotic risk and could not adjust for them in analyses.4,13 The National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Recipient Epidemiology and Donor Evaluation Study III (REDS-III) recipient database provides detailed transfusion and clinical information on all patients admitted to 12 hospitals. Comprehensive medication, comorbidity, and procedural data, as well as accurate timing of transfusion and medication administration in the REDS-III database enabled study of the association between RBC transfusion and thrombosis.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. REDS-III database

The domestic program of the NHLBI REDS-III program was structured as four hubs, each composed of a blood center and affiliated hospitals. The RTI International (Research Triangle Park, NC) served as the data coordinating center. Twelve hospitals (tertiary referral and community hospitals) contributed de-identified data into the REDS-III recipient database including all Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 codes associated with every hospitalization, laboratory results, medications and their time of administration, and detailed transfusion information including the time of product release from the blood bank. Institutional review board approval was obtained at each hub and the coordinating center.14

2.2 |. Study design

A study protocol outlining the analysis was developed prior to analysis. All inpatient hospital admissions from January 2013-September 2015 were analyzed. As children′s hospitals were not included in the REDS-III database, the limited admissions from patients <18 were excluded. Other excluded admissions were from outpatient transfusion or prevalent cases of thrombosis defined as anticoagulant administration at admission, admissions after a thrombotic event, history of thrombosis by diagnostic code, or thrombosis within 24 hours of admission. In the latter case, 24 hours was selected to avoid including thrombosis events prevalent already at admission. Time of blood product release from the blood bank was a reliable variable and present for all blood products across hospitals and was used as the surrogate for transfusion time. A thrombosis event was defined as the combination of a primary or secondary discharge diagnosis of arterial or venous thrombosis as a primary or secondary diagnosis at discharge (Table S1) and administration of a therapeutic anticoagulant or antiplatelet agent during that admission. Previous studies have shown the validity of using ICD codes to diagnose thrombosis.15,16 The timing of the thrombotic event was identified as the time of administration of therapeutic anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy because diagnosis codes apply to events throughout the admission. All anticoagulant medications in the database were reviewed and categorized as prophylactic or therapeutic based upon dose and/or route of administration (eg, enoxaparin >60 mg or intravenous unfractionated heparin). Only thrombotic events within the admission were considered.

2.3 |. Statistical analysis

A Cox proportional hazards regression model with transfusion as a time-dependent predictor was used to determine if transfusion increases the risk of thrombosis, adjusted for potential confounding variables. The hazard ratio for thrombosis comparing transfused and non-transfused patients was estimated from the Cox models, along with 95% confidence intervals and P values. The analysis used time since admission to hospital as the underlying time scale. Model variables included age, sex, study site, smoking, surgery, and comorbidity (metastatic cancer, liver disease, renal disease, congestive heart failure, diabetes, pulmonary disease, hypertension, and heart arrhythmia). Each comorbidity was evaluated individually. Obesity was evaluated by body mass index. The comorbidities were chosen to include clinical conditions known to increase thrombosis risk and were also present in comorbidity adjustment methods such as the Elixhauser index, a composite of 30 medical conditions that has outperformed other indices in predicting mortality and myocardial infarction.17,18 Procedure codes were grouped into clinically meaningful categories by the Clinical Classifications Software for Services and Procedures.19 Each category was manually reviewed and combined by surgical subspecialty. Patients were considered to be a current or previous smoker through the diagnosis codes 305.1 and V15.82. Body Mass Index was calculated from the recorded height and weight. Discharges from the hospital without thrombosis or in-hospital death were treated as competing events for in-hospital thrombosis. Cause specific hazards were calculated which treats the occurrence of a competing risk as a censoring event.

Logistic regression models were employed to emulate the methodology used in previous studies; the time interval between admission and either thrombosis, death, or discharge was assessed for whether an event occurred and whether any transfusions were administered.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Thrombosis and RBC transfusion occur frequently in hospitalized patients

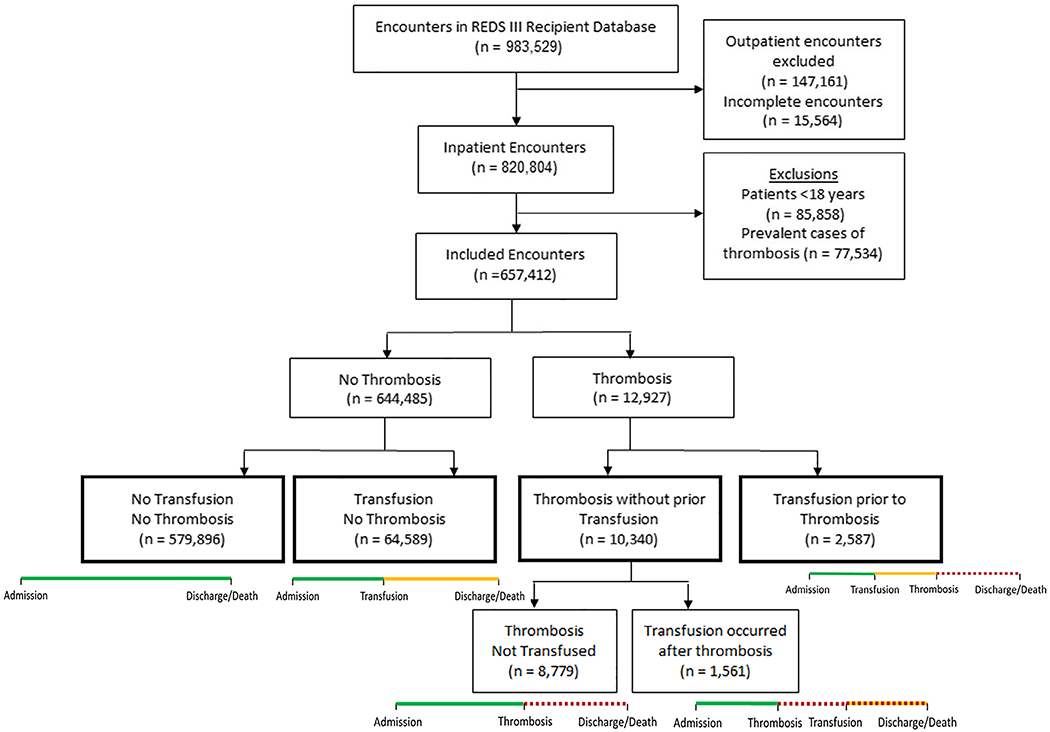

The REDS-III Recipient database contained 983 529 patient encounters of which 820 804 were inpatient admissions. After exclusion of children and prevalent cases of thrombosis, 657 412 admissions remained for analysis (Figure 1). Of these inpatient admissions, 67 176 (10.2%) received at least one RBC transfusion. At least one thrombotic event occurred in 12 927 (2%) of admissions; 6217 admissions (48%) had a venous thrombosis and 7344 admissions (57%) had arterial thrombosis. In 634 admissions, both an arterial and venous thrombosis occurred. Among the 12 927 admissions with a thrombotic event, 8779 (68%) had a thrombotic event and were never transfused, 2587 admissions (20%) had thrombosis after a RBC transfusion, and 1561 (12%) had a transfusion after the thrombotic event. Admissions with a transfusion after the thrombosis were combined with admissions that had thrombosis and were not transfused for analysis because both of these admissions had not been exposed to transfusion at the time of the thrombosis (thrombosis without prior transfusion group, n = 10 340, Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

Study flow diagram. The definition of thrombosis includes venous and arterial thrombosis

TABLE 1.

Demographics, surgical procedures, and comorbidities from hospital encounters within the REDS-III database

| No Transfusion No Thrombosis n = 579 896 |

Transfusion No Thrombosis n = 64 589 |

Thrombosis without prior transfusiona n = 10 340 |

Transfusion prior to Thrombosis n = 2587 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Median) | 57 | 63 | 66 | 64 |

| Male n (column %) | 267 448 (46.1%) | 30 666 (47.5%) | 5501 (53.2%) | 1354 (52.3%) |

| Lowest Hemoglobin Median (5th-95th percentile) | 11.1 (7.9-14.6) | 7.3 (5.5-9.3) | 9.7 (6.6-14.0) | 7.0 (5.4-9.1) |

| RBC units transfused (median, IQR) | 3(1-5) | 3 (2-6) | ||

| ICU admission | 1166 (0.2%) | 420 (0.7%) | 74 (0.7%) | 37 (1.4%) |

| ICU LOS Median (min-max) | 0 (0-33) | 0 (0-46) | 0 (0-38) | 2 (0-34) |

| Surgical Procedures n (column %) | ||||

| Vascular | 36 276 (6.3%) | 10 511 (16.3%) | 1714 (16.6%) | 706 (27.3%) |

| Thoracic | 23 999 (4.1%) | 5888 (9.1%) | 874 (8.5%) | 358 (13.8%) |

| General | 22 520 (3.9%) | 6650 (10.3%) | 703 (6.8%) | 425 (16.4%) |

| Ob/Gyn | 14 923 (2.6%) | 698 (1.1%) | 27 (0.3%) | 14 (0.5%) |

| Otolaryngology | 13 613 (2.4%) | 2719 (4.2%) | 890 (8.6%) | 240 (9.3%) |

| Orthopedic | 10 495 (1.8%) | 2084 (3.2%) | 132 (1.3%) | 78 (3.0%) |

| Cardiac | 8164 (1.4%) | 2248 (3.5%) | 716 (6.9%) | 266 (10.3%) |

| Neurosurgery | 7314 (1.3%) | 932 (1.4%) | 98 (1.0%) | 64 (2.5%) |

| Urology | 6012 (1.0%) | 1063 (1.7%) | 97 (0.9%) | 58 (2.2%) |

| Plastic | 4494 (0.8%) | 558 (0.9%) | 73 (0.7%) | 45 (1.7%) |

| Hematologic | 2805 (0.5%) | 1409 (2.2%) | 73 (0.7%) | 60 (2.3%) |

| Endocrine | 1881 (0.3%) | 48 (0.1%) | 11 (0.1%) | 3 (0.1%) |

| Ophthalmologic | 416 (0.1%) | 43 (0.1%) | 6 (0.1%) | 3 (0.1%) |

| Comorbidities n (column %) | ||||

| Hypertension (complicated or uncomplicated) | 269 733 (46.5%) | 35 215 (54.5%) | 6935 (67.1%) | 1575 (60.9%) |

| Diabetes Mellitus (complicated) | 121 705 (21.0%) | 16 972 (26.3%) | 3163 (30.6%) | 775 (30.0%) |

| Heart Arrhythmia | 115 620 (19.9%) | 21 018 (32.5%) | 4326 (41.8%) | 1309 (50.6%) |

| Pulmonary Disease | 124 529 (21.5%) | 13 767 (21.3%) | 2459 (23.8%) | 583 (22.5%) |

| Renal failure | 68 637 (11.8%) | 16 240 (25.1%) | 2014 (19.5%) | 708 (27.4%) |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 64 898 (11.2%) | 11 268 (17.5%) | 2282 (22.1%) | 612 (23.7%) |

| Liver Disease | 43 510 (7.5%) | 9011 (14.0%) | 769 (7.4%) | 342 (13.2%) |

| Metastatic cancer | 27 179 (4.7%) | 6467 (10.0%) | 875 (8.5%) | 326 (12.6%) |

| DM (uncomplicated) | 6785 (1.2%) | 1389 (2.2%) | 222 (2.2%) | 74 (2.9%) |

| Obesity | ||||

| BMI <25 (normal weight) | 216 304 (37.3%) | 35 321 (54.7%) | 5087 (49.2%) | 1645 (63.6%) |

| BMI 25-30 (overweight) | 120 874 (20.8%) | 18 612 (28.8%) | 2725 (26.4%) | 875 (33.8%) |

| BMI >30 (obese) | 57 614 (9.9%) | 8760 (13.6%) | 1271 (12.3%) | 439 (17.0%) |

| Smokers | 195 765 (34.1%) | 23 387 (36.3%) | 4340 (42.0%) | 1078 (41.7%) |

| Blood type | ||||

| Type O | 82 680 (14.3%) | 27 981 (43.3%) | 1578 (15.3%) | 1074 (41.5%) |

| Type A | 66 579 (11.5%) | 22 417 (34.7%) | 1553 (15.0%) | 997 (38.5%) |

| Type B | 24 822 (4.3%) | 8274 (12.8%) | 565 (5.5%) | 370 (14.3%) |

| Type AB | 7801 (1.3%) | 2771 (4.3%) | 208 (2.0%) | 107 (4.1%) |

Abbreviations: RBC, red blood cell; IQR, interquartile range; Ob/Gyn, obstetrics and gynecology; BMI, body mass index.

Combination of patients with thrombosis who were never transfused and patients who received a transfusion after their thrombotic event.

Demographics, transfusion information, surgical procedures, and comorbidities from the included hospital admissions are listed in Table 1. Median age varied between 57 to 66 years in the four analysis groups. The admissions with thrombosis had a higher percentage of males (admissions without transfusion: 46% males in the no thrombosis group vs 53% males in the thrombosis group; admissions with transfusion: 47.5% males in the no thrombosis group vs 52% in the thrombosis group). Median hemoglobin in transfused patients was 7.0 g/dL (range 5.4-9.1 g/dL) in patients with thrombosis and 7.3 g/dL (range 5.5-9.3 g/dL) in patients without thrombosis. A median of three units of RBC were given during admissions requiring red blood cell transfusion (Table 1). A third of admissions had only one unit transfused. Transfusions occurred throughout the admission and median time between hospitalization and transfusion was 33 hours (IQR 8-86 hours). For the 2587 encounters with thrombosis and transfusion, median time from last transfusion to thrombosis event was 49 hours (IQR 19-111 hours).

The most common surgical procedures were vascular surgery, thoracic procedures, and general surgery. The most frequent comorbidities associated with the hospital admissions were hypertension, diabetes with complications, arrhythmias, and pulmonary disease (Table 1).

3.2 |. Surgery and medical comorbidities are associated with a risk for thrombosis

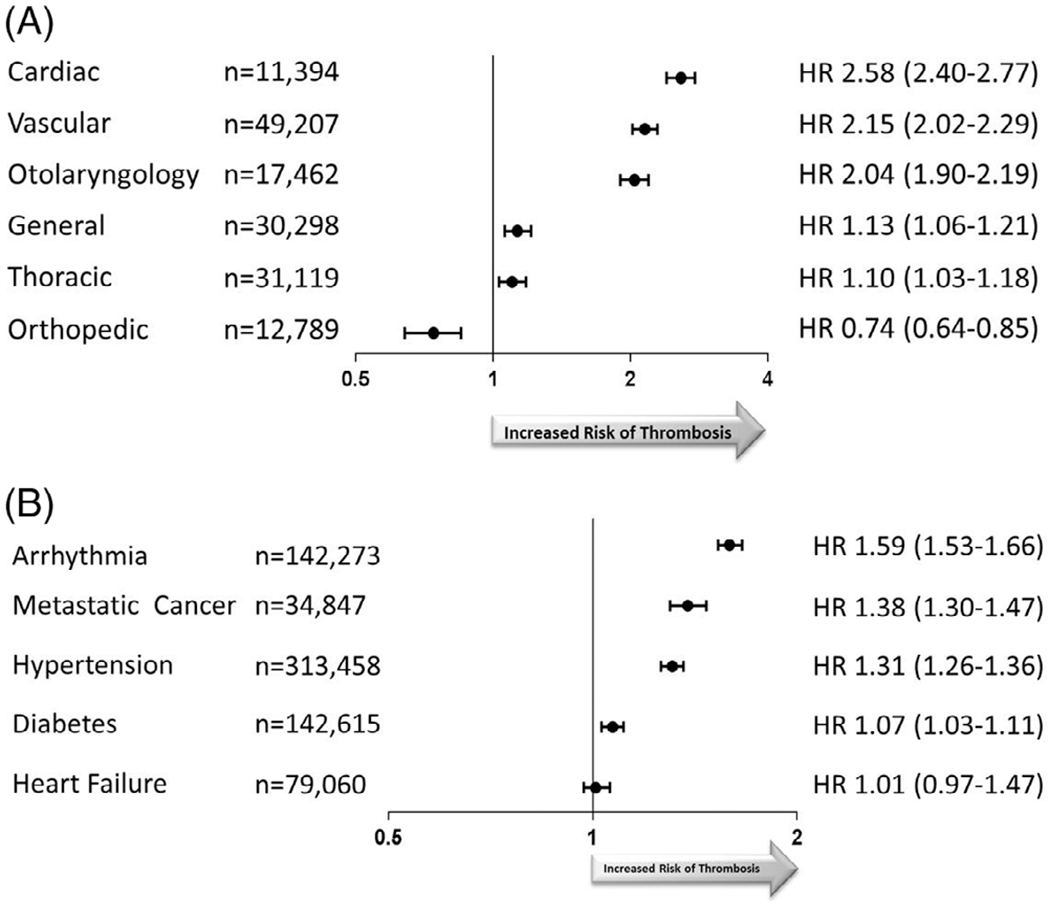

Many surgical procedures were associated with thrombosis (Figure 2A) including cardiac surgery [Hazard Ratio (HR) 2.58 (95% CI 2.40-2.77)] and vascular surgery, [HR 2.15 (2.02-2.29)]. Otolaryngology was also associated with thrombosis [HR 2.04 (1.90-2.19)], possibly due to inclusion of surgery for head and neck cancers in this category. Orthopedic surgery was associated with a reduced risk of venous or arterial thrombosis during the hospitalization [HR 0.74 (0.64-0.85)]. When venous and arterial thrombotic events were evaluated independently, orthopedic surgery was associated with an increased thrombotic risk for venous [HR 1.19 (1.01-1.41)] but not arterial events [HR 0.59 (0.47-0.76)]. Similarly, many medical comorbidities were associated with thrombosis risk (Figure 2B), including arrhythmias 1.59 (1.53-1.66), hypertension [HR 1.31 (1.26-1.36)], metastatic cancer [HR 1.38 (1.30-1.47)], and diabetes [HR 1.07 (1.03-1.11)].

FIGURE 2.

A, Hazard ratio of arterial and venous thrombosis in relation to type of surgery. Surgical procedures were grouped by surgical subspecialty. Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals from Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for age, sex, hospital, transfusion, and other surgical procedures. The reference groups are patients without that surgical procedure. B, Hazard ratio of arterial and venous thrombosis in relation to medical comorbidities. Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals from Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for age, sex, hospital, transfusion, and surgical procedures. The reference groups are patients without that comorbidity

3.3 |. RBC transfusion is not associated with a risk of venous and arterial thrombosis after adjustment

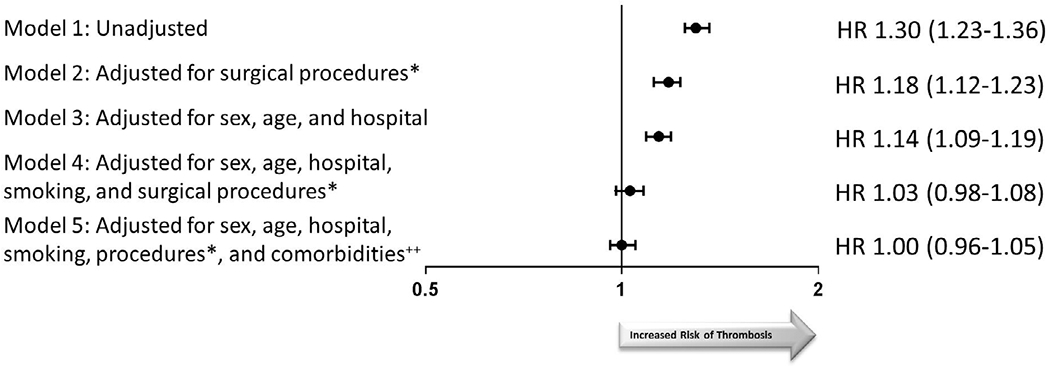

Note, RBC transfusion was associated with an increased risk of thrombosis [HR 1.30 (1.23-1.36)] in unadjusted analyses (Figure 3). This risk increased with the number of RBC units transfused (P < .001), However, after adjustment for surgical procedures, age, sex, hospital, and comorbidities, no statistically significant association remained between RBC transfusion and thrombotic risk [HR 1.00 (0.96-1.05)]. Adjusting for surgical procedures caused the largest change of point estimates. Evaluation of only arterial thrombotic events in the unadjusted analysis model also showed an association between RBC transfusion and thrombosis [HR 1.09 (1.03-1.17)], but there was no effect after adjustment for sex, age, hospital, and smoking [HR 0.96 (0.90-1.02)]. Similarly, an association between transfusion and venous thrombosis was found in unadjusted models [HR 1.58 (1.49-1.68)], but was not present after adjustment for sex, age, hospital, surgical procedures, comorbidities, smoking, and BMI [HR 0.99 (0.93-1.06)].

FIGURE 3.

Association between RBC transfusion and arterial and/or venous thrombosis. Hazard ratios and P values from Cox proportional hazards model. *Cardiac, Vascular, Orthopedic, General, Otolaryngology, and Thoracic Surgery. ++Comorbidities include arrhythmia, chronic heart failure, chronic lung disease, diabetes (complicated and uncomplicated), hypertension, liver disease, metastatic cancer, and renal failure

3.4 |. Logistic regression models including admissions with transfusion after thrombosis find an association between RBC transfusion and thrombosis

Since the time from transfusion to event is not implicitly taken into account in previous studies using logistic regression modeling, the 1561 admissions with transfusion after the thrombotic event were considered as having transfusion and thrombosis, in addition to the 2587 admissions with a transfusion prior to the thrombotic event. In an unadjusted logistic regression model, transfusion was associated with a significant thrombosis risk [OR 2.31 (2.21-2.41)]. Adjustment for sex, age, hospital, surgical procedure and comorbidities reduced this association [OR 1.47 (1.40-1.54)]. Additional adjustment for smoking and BMI further reduced the association, but it remained statistically significant [OR 1.16 (1.11-1.22)].

4 |. DISCUSSION

The REDS-III recipient database is a unique dataset with detailed information about timing of transfusions and medications that allowed us to accurately define a thrombotic episode and its temporal relationship to RBC transfusion. Most patients were transfused within the first 1 to 2 days of hospitalization and for patients who experienced thrombosis, the events typically occurred days after the transfusion. Univariate analyses showed an association of venous or arterial thrombosis with surgical procedures and medical comorbidities, as well as RBC transfusion. After adjustment for these various risk factors, however, RBC transfusion was not an independent predictor of arterial and/or venous thrombosis. Our findings do not rule out the possibility of a patient subset where RBC transfusion increases risk for thrombosis, such as patients with an underlying genetic hyper-coagulable risk, but they do indicate that RBC transfusion does not appear to be an important risk factor for thrombosis in most patients.

There are four potential reasons why our study found results contrary to some previous reports. First, administrative datasets provide diagnostic and procedure codes for the hospitalization but the temporal sequence of transfusion and thrombosis during the hospitalization is not always known. Within the REDS-III dataset, there were 1561 admissions with transfusion occurring after the thrombotic event. If the temporal sequence was not known, these admissions would have been combined with the 2587 admissions in which transfusion occurred before the thrombosis, and 38% of thrombosis cases would have been misclassified as having ostensibly been caused by the transfusion. Some groups addressed this issue by evaluating preoperative and/or intraoperative transfusion with the risk of postoperative VTE and found variable results.2,3 Second, we excluded prevalent cases of thrombosis by excluding thrombosis in the first 24 hours of admission, a diagnostic code of history of thrombosis, and encounters after a thrombotic event. Third, the number of comorbidities available in a database can influence the ability to adjust for confounders. We included comorbidities associated with either the risk for transfusion or thrombosis individually instead of using combined scoring systems such as the Elixhauser index as a discrete score. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Class is a scoring system for physiologic status between one (healthy) and six (brain dead) and has been shown to predict post-operative mortality.20 Patients with higher ASA scores had higher incidence of postoperative medical complications,21 but prediction of individual outcomes have not been established. Lastly, prior studies used logistic regression modeling to evaluate the association between transfusion and thrombosis using only selected covariates as potential confounders, because of statistical significance of the association. We included clinically relevant covariates and potential confounders regardless if they had statistical significance. Additionally, we analyzed cause-specific hazards which are a measure of risk and not the cumulative effect of that risk. Overall, understanding the temporal relationship between RBC transfusion and thrombosis, appropriate adjustment for confounders, and use of cause-specific hazards are likely reasons why we did not find an association between RBC transfusion and thrombosis.

Our study has several important limitations. In order to provide an accurate assessment of a new thrombosis, three types of admissions with prevalent cases of thrombosis were excluded: admissions with diagnosis codes for history of thrombosis, patients with thrombosis within 24 hours of admission, and admissions after a thrombotic event. Consequently, this study does not address if transfusion would affect the risk of thrombosis in patients with a previous thrombotic event. Our definition of thrombosis includes a combination of diagnoses codes and medication administration. Deaths due to thrombosis may not be coded as such if thrombosis was not known or even suspected at the time of death. Still, underdiagnosis of thrombosis at the time of death is unlikely to have differed systematically between transfused and non-transfused patients and should thus only affect the precision of the risk estimates and not the point estimates. We also evaluated hospitalized patients without specific attention to higher-risk cohorts, such as those with underlying thrombophilia, sickle cell disease, or leukostasis. The widespread use of prophylactic anticoagulation in hospitalized patients could have mitigated the risk of thrombosis but was not considered in the analysis. Surgical procedures were grouped by surgical subspecialty based on CPT codes and Clinical Classifications Software for Services and Procedures categories and thus procedure duration or complexity not embodied by the procedure name could not be determined. Time of blood product release from the blood bank was used as the surrogate for transfusion time, but the actual transfusion, especially in surgical areas, may have occurred hours later. Lastly, other studies finding an association between RBC transfusion and thrombosis included thrombotic events up to 30-days post-operatively.2,3 Because the REDS-III dataset is admission-based and patients could not reliably be followed to other hospitals, our study evaluated only in-hospital events and would not be able to determine if an inpatient transfusion was associated with a risk of thrombosis that extended after hospital discharge, or if an outpatient transfusion was associated with subsequent thrombosis.

Surgical procedures, medical comorbidities, and RBC transfusion are associated with a risk for thrombosis. In this patient cohort, after adjustment for age, sex, medical comorbidities, and surgical procedures, RBC transfusion was not associated with a risk for inpatient arterial and venous thrombosis. Thrombosis risk may be therefore driven by underlying comorbidities and surgical procedures and not RBC transfusion.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The study was funded through a contract from the NHLBI. The study investigators and scientists at NHLBI designed, conducted, and reported the study outcomes.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No support from any organization for the submitted work, no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years [G.E., R.G.H., D.Z., M.W., D.B.], Consultancy for CSL Behring and Quercetin Pharmaceuticals (L.B.K.); Haemonetics, Grifols, and Sanofi (J.K.); research grant funding and consultancy from Novo Nordisk (A.E.M.), and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

All authors were involved in the study design, analysis, and manuscript writing.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at https://biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/studies/reds_iii/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Garcia-Roa M, Del Carmen Vicente-Ayuso M, Bobes AM, et al. Red blood cell storage time and transfusion: current practice, concerns and future perspectives. Blood Transfus. 2017;15(3):222–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goel R, Patel EU, Cushing MM, et al. Association of perioperative red blood cell transfusions with venous thromboembolism in a North American registry. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(9):826–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleming FJ, Kim MJ, Salloum RM, Young KC, Monson JR. How much do we need to worry about venous thromboembolism after hospital discharge? A study of colorectal surgery patients using the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53(10):1355–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xenos ES, Vargas HD, Davenport DL. Association of blood transfusion and venous thromboembolism after colorectal cancer resection. Thromb Res. 2012;129(5):568–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khorana AA, Francis CW, Blumberg N, Culakova E, Refaai MA, Lyman GH. Blood transfusions, thrombosis, and mortality in hospitalized patients with cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(21):2377–2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan TW, Farber A, Hamburg NM, et al. Blood transfusion for lower extremity bypass is associated with increased wound infection and graft thrombosis. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2013; 216(5):1005–14.e2; quiz 31-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D′Alessandro A, D′Amici GM, Vaglio S, Zolla L. Time-course investigation of SAGM-stored leukocyte-filtered red bood cell concentrates: from metabolism to proteomics. Haematologica. 2012;97(1): 107–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouchard BA, Orfeo T, Keith HN, et al. Microparticles formed during storage of red blood cell units support thrombin generation. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;84(4):598–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanias T, Lanteri MC, Page GP, et al. Ethnicity, sex, and age are determinants of red blood cell storage and stress hemolysis: results of the REDS-III RBC-Omics study. Blood Adv. 2017;1(15):1132–1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore C, Tymvios C, Emerson M. Functional regulation of vascular and platelet activity during thrombosis by nitric oxide and endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Thromb Haemost. 2010;104(2):342–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lowe GD, Lee AJ, Rumley A, Price JF, Fowkes FG. Blood viscosity and risk of cardiovascular events: the Edinburgh Artery Study. Br J Haematol. 1997;96(1):168–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Byrnes JR, Wolberg AS. Red blood cells in thrombosis. Blood. 2017; 130(16):1795–1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar MA, Boland TA, Baiou M, et al. Red blood cell transfusion increases the risk of thrombotic events in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2014;20(1):84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karafin MS, Bruhn R, Westlake M, et al. Demographic and epidemiologic characterization of transfusion recipients from four US regions: evidence from the REDS-III recipient database. Transfusion. 2017;57 (12):2903–2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang MC, Fan D, Sung SH, et al. Validity of using inpatient and outpatient administrative codes to identify acute venous thromboembolism: the CVRN VTE study. Med Care. 2017;55(12):e137–e143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White RH, Garcia M, Sadeghi B, et al. Evaluation of the predictive value of ICD-9-CM coded administrative data for venous thromboembolism in the United States. Thromb Res. 2010;126(1):61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Southern DA, Quan H, Ghali WA. Comparison of the elixhauser and Charlson/Deyo methods of comorbidity measurement in administrative data. Med Care. 2004;42(4):355–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharabiani MT, Aylin P, Bottle A. Systematic review of comorbidity indices for administrative data. Med Care. 2012;50(12):1109–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Clinical Classifications Software for Services and Procedures 2018. [cited 2018]. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs_svcsproc/ccssvcproc.jsp.

- 20.Moreno RP, Pearse R, Rhodes A. American Society of Anesthesiologists Score: still useful after 60 years? Results of the EuSOS Study. Rev Bras Terap Intens. 2015;27(2):105–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hackett NJ, De Oliveira GS, Jain UK, Kim JY. ASA class is a reliable independent predictor of medical complications and mortality following surgery. Int J Surg. 2015;18:184–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at https://biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/studies/reds_iii/.