Abstract

Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) is a valuable tool for measuring molecular distances and the effects of biological processes such as cyclic nucleotide messenger signaling and protein localization. Most FRET techniques require two fluorescent proteins with overlapping excitation/emission spectral pairing to maximize detection sensitivity and FRET efficiency. FRET microscopy often utilizes differing peak intensities of the selected fluorophores measured through different optical filter sets to estimate the FRET index or efficiency. Microscopy platforms used to make these measurements include wide-field, laser scanning confocal, and fluorescence lifetime imaging. Each platform has associated advantages and disadvantages, such as speed, sensitivity, specificity, out-of-focus fluorescence, and Z-resolution.

In this study, we report comparisons among multiple microscopy and spectral filtering platforms such as standard 2-filter FRET, emission-scanning hyperspectral imaging, and excitation-scanning hyperspectral imaging. Samples of human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells were grown on laminin-coated 28 mm round gridded glass coverslips (10816, Ibidi, Fitchburg, Wisconsin) and transfected with adenovirus encoding a cAMP-sensing FRET probe composed of a FRET donor (Turquoise) and acceptor (Venus). Additionally, 3 FRET “controls” with fixed linker lengths between Turquoise and Venus proteins were used for inter-platform validation. Grid locations were logged, recorded with light micrographs, and used to ensure that whole-cell FRET was compared on a cell-by-cell basis among the different microscopy platforms. FRET efficiencies were also calculated and compared for each method. Preliminary results indicate that hyperspectral methods increase the signal-to-noise ratio compared to a standard 2-filter approach.

Keywords: Hyperspectral, Fluorescence, Spectroscopy, Microscopy, FRET, Spectral, Signature

1. INTRODUCTION

Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) is a distance-dependent process by which energy is nonradiatively transferred from an excited fluorescent molecule, called the donor, to another fluorescent molecule, called the acceptor.1 Several criteria must be met in order for this energy transfer to take place, such as a minimum distance between the fluorescent molecules (1–10 nm) and an overlap between the emission spectrum of the donor molecule and the excitation spectrum of the acceptor molecule.2–4 As the efficiency of this energy transfer is directly related to the distance between the donor-acceptor pair, FRET is often used as a molecular ruler to determine whether two molecules interact.

Many FRET microscopy techniques have been developed to take advantage of this phenomenon, each with their advantages and disadvantages. The simplest technique utilizes widefield microscopy and specially chosen filter sets. For example, one may make use of a well-established donor-acceptor pair and associated fluorescence filters to excite the donor molecule and compare emitted light captured using the donor’s emission filter compared to the acceptor’s emission filter.5 However, as with most widefield microscopy applications, out-of-focus light limits signal resolution and therefore data interpretation. Many labs, including ours, have taken advantage of confocal microscopy’s ability to select only in-focus light and segment the z-dimension, resulting in highly accurate FRET measurements across entire cells.6 Furthermore, we have used the confocal approach in conjunction with spectral imaging technologies originally created by NASA7 to isolate the individual fluorescent molecules by their spectral signatures.6 Doing so has allowed delineation of the fluorophores in the donor-acceptor pair from other labels and even autofluorescence, resulting in highly accurate FRET measurements. However, the major drawback of this technique is the time require to complete such a scan. A five-dimensional scan (x, y, z, λ, t) can take several minutes to acquire all necessary information to facilitate accurate FRET measurements.

We have recently developed a technique that greatly reduces the time needed for spectral scans. Our technique, called hyperspectral imaging fluorescence excitation-scanning (HIFEX) microscopy, scans the excitation spectrum of fluorescent molecules by varying excitation light from a Xe arc lamp in narrow bands using an array of thin-film tunable filters in a tunable filter assembly and collects all emitted light of wavelengths longer than our dichroic beam splitter.8 This method allows detection of appreciably more emitted light while simultaneously reducing the acquisition time required for data collection and has even shown a higher signal-to-noise ratio of unmixed spectral data when compared to similar emission-scanning systems.9,10 Initial studies utilizing this system’s approach to investigate FRET signals appear promising. Here, we present data comparing the spectral emission scanning confocal approach with the HIFEX approach on samples fixed on gridded coverslips which allowed us to compare the same set of cells across multiple microscopy platforms.

2. METHODS

2.1. Sample preparation

Human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells were cultured as described previously.6,11,12 Cells were grown to confluency on 28 mm round gridded glass coverslips (10816, Ibidi) and transfected with adenovirus encoding a cAMP-sensing FRET probe composed of a FRET donor (Turquoise) and acceptor (Venus). After confluency and transfection, the gridded coverslips were mounted on slides using ProLong Diamond Antifade Mountant (P36965, Invitrogen).

2.2. Image acquisition

Imaging was performed on two microscopy platforms: spectral FRET imaging using a Nikon A1R confocal microscope6 and a custom hyperspectral imaging fluorescence excitation-scanning (HIFEX) widefield microscope.8 All images were acquired with respect to grid locations of the coverslips, which were logged and recorded with light micrographs to allow data acquisition from the same cell clusters on each microscopy platform.

The Nikon A1R confocal microscope collected image stacks at excitation wavelengths of 405 nm (8% laser intensity) and 562 nm (6% laser intensity) and emission wavelengths from 412 nm to 698 nm in 6 nm increments. Spectral images were collected with a pinhole diameter of 2 airy disk units (AU). For this application, a 60X water immersion objective (Plan Apo VC 60X DIC N2 WI NA-1.3; Nikon Instruments) and 32 channel photomultiplier tube (PMT) spectral detector were used.

The HIFEX widefield microscope utilized a Xe arc lamp and thin-film tunable filter assembly for spectral excitation over the range of 340 nm to 485 nm and emission detection from 495 nm to 1000 nm. Filter cubes were used to separate excitation and emission light at 458 nm and 495 nm for donor and acceptor signals. These filter cubes consisted of dichroic beamsplitters (FF458-Di02 and FF495-Di03, Semrock, Inc.) and long-pass emission filters (BLP01-458R and FF01 496/LP-25, Semrock Inc.) Similar to the confocal platform, a 60X water immersion objective (Plan Apo VC 60X/1.2 WI ∞.0.15–0.18 WD 0.27, Nikon Instruments) was used. Emitted light was captured with an sCMOS camera (Prime 95B, Photometrics).

2.3. Image processing and analysis

Following image data collection, images were stitched using Fiji’s Grid/Collection Stitching plugin.13 Stitched images were opened in Fiji to ensure visual accuracy. The stitched HIFEX spectral image cube was then separated into respective spectral bands for unmixing, as described previously.14 Confocal spectral image cubes were also unmixed, as described previously.6 All calculations were performed using custom MATLAB scripts and previously acquired control library data for each fluorescent molecule. Unmixed HIFEX and confocal data were used to estimate FRET efficiencies and/or indices of manually selected cells as previously described.6,11,15–17

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Upon utilizing two microscopy platforms, confocal microscopy and hyperspectral imaging fluorescence excitation scanning (HIFEX) microscopy, the initial result yielded similar fields of view. This allowed confirmation that grid locations of each scan were well documented and that subsequent stitched images from each microscopy platform would be visually comparable. As Figure 1 shows, the same cell clusters from the fixed slide are readily identifiable between the two microscopy platforms. As expected, the confocal image is less hazy than the HIFEX image, as the HIFEX image was captured with widefield microscopy. It is worth noting that since factors such as detector type and scanning method vary between the two systems, the HIFEX and confocal images are slightly different sizes, both in terms of pixel count and viewing area.

Figure 1.

Stitched HIFEX and confocal fluorescence images. (Left) The HIFEX image shows all fluorescing molecules excited by the excitation-scanning system. (Right) The confocal image shows all fluorescing molecules excited by the lasers on the confocal system. Each image is a sum of the intensity through the spectral data cube.

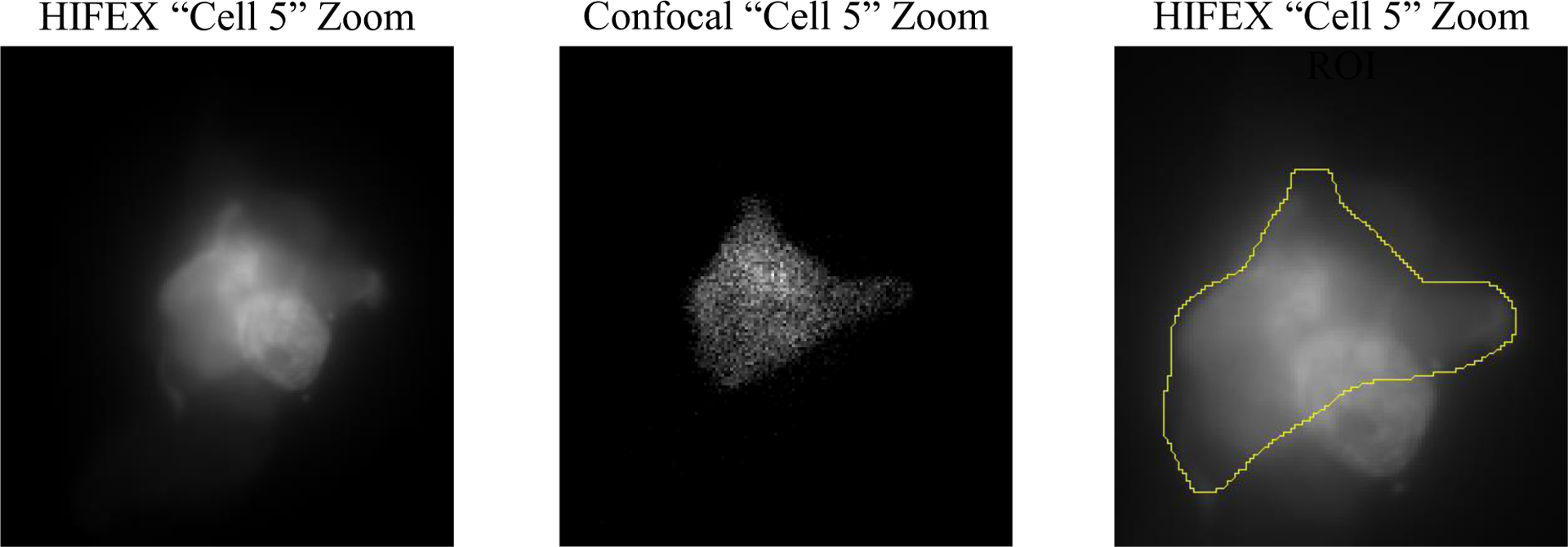

Regions of interest were chosen such that cells appearing to be abundantly bright were ignored. Extremely bright cells are often compromised in viability, increasingly the likelihood that any conclusions drawn from these cells would generate misleading data. Figure 2 shows the 5 cells selected for this initial study. The ovals in Figure 2 serve only to draw attention to the individual cells used to obtain data, while Figure 3 demonstrates two important points. First, that a high zoom is necessary to outline the individual features of each cell to ensure background, stray, out-of-focus, or otherwise inappropriate light is excluded from the region of interest. Second, that since the HIFEX data was acquired with widefield microscopy, regions of interest needed to be drawn with respect to the confocal microscopy image in order to maintain a direct comparison.

Figure 2.

Regions of interest selected for FRET estimation comparison among microscopy platform. (Left) The stitched confocal fluorescence image from Figure 1, provided as a reference for the selected cells. (Right) The same confocal fluorescence image with five cells highlighted for FRET estimation. The selected regions are color-coded for ease of identification. 1. Red. 2. Blue. 3. Green. 4. Magenta. 5. Yellow.

Figure 3.

Zoomed images of the fifth selected region from Figure 2. (Left) A zoomed image of “cell 5” from the HIFEX image. (Center) A zoomed image of “cell 5” from the confocal image. (Right) An image of the same “cell 5” captured using the HIFEX approach with a region of interest drawn to coincide with the cell shown in the confocal image. As the HIFEX method utilizes widefield microscopy, its images potentially include light from out-of-focus cells. By selecting only the regions which also appear in the confocal image, a more appropriate comparison may be made between FRET estimations.

As FRET approximation via fluorescence excitation-scanning is a newer concept, Figure 4 has been included to demonstrate the four scans necessary for FRET calculations. Figure 4 shows the scans acquired with the 458 nm dichroic filter cube and the 495 nm dichroic filter cube, unmixed into their respective fluorescence signals. For the sake of direct comparison, each image has had the maximum displayed value set to 30,000 (of the total available 65,535). As expected, unmixing the data collected using the 458 nm dichroic filter cube resulted in mostly donor signal, as the acceptor is difficult to excite with such short wavelengths. (The excitation and emission spectra of the donor and acceptor are shown in Figure 5.18–20) However, upon excitation of wavelengths longer than 475 nm, the acceptor is more easily excitable than the donor. Thus, it is unsurprising that the unmixed data from the 495 nm dichroic filter cube shows the acceptor as the most intense of all of the fields of view, as the acceptor molecules are not only directly excited by the light source, but are also potentially excited by any nearby donor molecules via FRET.

Figure 4.

Linearly unmixed excitation-scanning (HIFEX) spectral images corresponding to the donor and acceptor molecules with respect to the dichroic filter cube used to obtain the images. All pixel intensities were scaled such that the maximum displayed value was 30,000 (of the total available 65,535) to provide a visual representation of the differences in fluorescence intensities among the unmixed images. (Top Left) The unmixed donor image acquired using the 458 nm dichroic filter cube. (Bottom Left) The unmixed acceptor image acquired using the 458 nm dichroic filter cube. (Top Right) The unmixed donor image acquired using the 495 nm dichroic filter cube. (Bottom Right) The unmixed acceptor image acquired using the 495 nm dichroic filter cube. The unmixed acceptor image acquired using the 458 dichroic filter cube is the dimmest image, as the acceptor is difficult to excite with wavelengths shorter than 475 nm. However, the unmixed acceptor acquired using the 495 dichroic filter cube is the brightest image, as the acceptor can potentially be excited directly or through FRET.

Figure 5.

The excitation and emission spectra of the donor and acceptor FRET molecules. Excitation spectra are shown as dashed lines. Emission spectra are represented by solid lines. The donor spectra are shown as blue and the acceptor spectra are shown as orange. Of particular interest for the HIFEX method are the excitation spectra at the 450 nm and 495 nm regions, as the intensities plotted demonstrate the difficulty of exciting the acceptor when using the 458 nm dichroic filter cube and the change in preferential molecule excitation around 475 nm.

Comparison of the overall fluorescence images, summed intensity images, and the unmixed intensity images indicated that the two datasets were a suitable platform to compare FRET measurements among systems. Interestingly, while the FRET measurements made with the confocal data adhere to the traditional FRET efficiency values between 0 and 1, the index created via analysis of the HIFEX images reported numbers between −1 and 1. Shown in Table 1, the five cells selected here had FRET efficiency values between 0.17 and 0.24 when the confocal images were analyzed, yet the HIFEX data yielded FRET indices of either about −0.06 or −0.20. Furthermore, there appear to be two relationships between the confocal data and the HIFEX data. To elucidate any possible connection between the two values, the HIFX FRET index values were divided by the confocal FRET efficiencies. Curiously, the ratio was either near −0.28 or −0.96.

Table 1.

FRET indices and efficiencies for two methods of calculating FRET. The second column reports the FRET indices per cell when estimated using the HIFEX method. The third column reports the FRET efficiencies per cell when calculated using the confocal method. The last column is a ratio of the HIFEX FRET index to the confocal FRET efficiency.

| Cell # | HIFEX FRET Index | Confocal FRET Efficiency | HIFEX/Confocal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell 1 | −0.212 | 0.221 | −0.957 |

| Cell 2 | −0.060 | 0.215 | −0.281 |

| Cell 3 | −0.203 | 0.208 | −0.978 |

| Cell 4 | −0.049 | 0.171 | −0.283 |

| Cell 5 | −0.062 | 0.234 | −0.264 |

There are a few potential reasons for the discrepancies between the FRET indices/efficiencies reported by the two methods shown here. First and most obviously, confocal microscopy allows for sectioning of the focal plane such that a single cell layer may be isolated for study. The cells used for this study (HEK293) are notorious for growing in clusters that often overlap. Some differences in FRET measurements may simply be inclusion of cells above of below the focal plane in the HIFEX image that were absent from the confocal image. Second, the FRET measurements reported from the confocal microscopy data are a result of rigorous and proven methods that account for factors such as the quantum yield of the individual fluorescent molecules in the FRET pair. The method used here to calculate FRET indices from the HIFEX data made several assumptions, including those of quantum yield of the fluorescent molecules, concentration of the probe in the sample, and the efficiencies of the measurement system.17 Third, the images used for unmixing the data acquired by the HIFEX microscopy system were not corrected for background light or wavelength-dependent illumination intensity.

4. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE WORK

FRET measurements among microscopy platforms is a relatively uninvestigated topic. It should be quite important to verify that FRET measurements made on one system agree with those made on another. Otherwise, conclusions drawn from one FRET experiment may directly disagree with that of similar experiment when, in fact, the only difference may be a scaling term that would adjust the values so that conclusions agree. Here, we have shown preliminary results that begin to approach that verification. However, it is clear that there are inconsistencies somewhere in our HIFEX results, as the values among indices do not have a clear correlation with those reported using confocal microscopy. Furthermore, manually selected regions in both images to ensure comparable cell geometries. It is possible that some or all of the selected cells were outliers.

In the future, we will reevaluate the calculation of our FRET index from HIFEX datasets. Furthermore, we will collect data using multiple types of FRET probes, such as those with varied lengths between the donor and acceptor proteins which should allow us to more accurately relate FRET efficiency values. Finally, we plan to include other types of microscopy platforms, such as fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM) to better assess the variation among platforms.

5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the Abraham Mitchell Cancer Research fund as well as the American Heart Association grant 18PRE34060163, National Science Foundation grant NSF 1725937, and National Institutes of Health grants P01HL066299, R01HC137030, UL1 TR001417, S10RR027535, R01HL058506, and S10OD020149 for supporting this work. Drs. Leavesley and Rich also disclose financial interest in a start-up company, SpectraCyte LLC, formed to commercialize spectral imaging technologies.

REFERENCES

- [1].Sekar RB and Periasamy A, “Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) microscopy imaging of live cell protein localizations,” The Journal of cell biology 160(5), 629–633 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Förster T, “Zwischenmolekulare energiewanderung und fluoreszenz,” Annalen der physik 437(1–2), 55–75 (1948). [Google Scholar]

- [3].Clegg RM, “The history of FRET,” [Reviews in Fluorescence 2006], Springer, 1–45 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lakowicz JR, [Principles of fluorescence spectroscopy, 3rd ed.], Springer US; (2006). [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sun Y, Wallrabe H, Seo S-A and Periasamy A, “FRET microscopy in 2010: the legacy of Theodor Förster on the 100th anniversary of his birth,” ChemPhysChem 12(3), 462–474 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Annamdevula NS, Sweat R, Griswold JR, Trinh K, Hoffman C, West S, Deal J, Britain AL, Jalink K, Rich TC and Leavesley SJ, “Spectral imaging of FRET-based sensors reveals sustained cAMP gradients in three spatial dimensions,” Cytometry A 93(10), 1029–1038 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Goetz AFH, “Measuring the earth from above: 30 years (and counting) of hyperspectral imaging,” Photonics Spectra 45(6), 42–47 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- [8].Deal J, Britain A, Rich T and Leavesley S, “Excitation-scanning hyperspectral imaging microscopy to efficiently discriminate fluorescence signals,” J. Vis. Exp(150), e59448 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Favreau PF, Hernandez C, Lindsey AS, Alvarez DF, Rich TC, Prabhat P and Leavesley SJ, “Thin-film tunable filters for hyperspectral fluorescence microscopy,” J. Biomed. Opt 19(1), 1–11 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Favreau PF, Hernandez C, Heaster T, Alvarez DF, Rich TC, Prabhat P and Leavesley SJ, “Excitation-scanning hyperspectral imaging microscope,” J. Biomed. Opt 19(4), 046010 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Leavesley SJ, Britain AL, Cichon LK, Nikolaev VO and Rich TC, “Assessing FRET using spectral techniques,” Cytometry A 83(10), 898–912 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Rich TC, Fagan KA, Nakata H, Schaack J, Cooper DM and Karpen JW, “Cyclic nucleotide–gated channels colocalize with adenylyl cyclase in regions of restricted cAMP diffusion,” J. Gen. Physiol 116(2), 147–161 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S and Schmid B, “Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis,” Nature methods 9(7), 676 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Deal J, Britain A, Rich T and Leavesley S, “Excitation-Scanning Hyperspectral Imaging Microscopy to Efficiently Discriminate Fluorescence Signals,” JoVE(150), e59448 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rich TC, Britain AL, Stedman T and Leavesley SJ, “Hyperspectral imaging of FRET-based cGMP probes,” [Guanylate Cyclase and Cyclic GMP], Springer, 73–88 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Leavesley SJ, Nakhmani A, Gao Y and Rich TC, “Automated image analysis of FRET signals for subcellular cAMP quantification,” [cAMP Signaling], Springer, 59–70 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Griswold JR, [Detecting Fret Using Excitation-Scanning Hyperspectral Imaging], Mobile, AL: University of South Alabama; (2018). [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lambert TJ, “FPbase: A community-editable fluorescent protein database,” Nature methods 16(4), 277 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Goedhart J, Von Stetten D, Noirclerc-Savoye M, Lelimousin M, Joosen L, Hink MA, Van Weeren L, Gadella TW Jr and Royant A, “Structure-guided evolution of cyan fluorescent proteins towards a quantum yield of 93%,” Nature communications 3, 751 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kremers G-J, Goedhart J, van Munster EB and Gadella TW, “Cyan and yellow super fluorescent proteins with improved brightness, protein folding, and FRET Förster radius,” Biochemistry 45(21), 6570–6580 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]