Abstract

Background

Although healthcare institutions receive many unsolicited compliment letters, these are not systematically conceptualised or analysed. We conceptualise compliment letters as simultaneously identifying and encouraging high-quality healthcare. We sought to identify the practices being complimented and the aims of writing these letters, and we test whether the aims vary when addressing front-line staff compared with senior management.

Methods

A national sample of 1267 compliment letters was obtained from 54 English hospitals. Manual classification examined the practices reported as praiseworthy, the aims being pursued and who the letter was addressed to.

Results

The practices being complimented were in the relationship (77% of letters), clinical (50%) and management (30%) domains. Across these domains, 39% of compliments focused on voluntary non-routine extra-role behaviours (eg, extra-emotional support, staying late to run an extra test). The aims of expressing gratitude were to acknowledge (80%), reward (44%) and promote (59%) the desired behaviour. Front-line staff tended to receive compliments acknowledging behaviour, while senior management received compliments asking them to reward individual staff and promoting the importance of relationship behaviours.

Conclusions

Compliment letters reveal that patients value extra-role behaviour in clinical, management and especially relationship domains. However, compliment letters do more than merely identify desirable healthcare practices. By acknowledging, rewarding and promoting these practices, compliment letters can potentially contribute to healthcare services through promoting desirable behaviours and giving staff social recognition.

Keywords: patient-centred care, communication, healthcare quality improvement, patient safety

Introduction

Compliment letters have been identified as a potential source of patient-generated data for improving healthcare quality and safety.1 A letter of compliment refers to unsolicited positive feedback on specific encounters that patients and their families (herein patients) send via post or email without expecting a response. Hospitals receive many such letters, ranging from personalised letters sent to front-line staff to lengthy letters sent to senior managers. Yet, there is no conceptualisation of their value or standardised procedures for receiving, analysing or benefiting from them.1 2 By contrast, other forms of patient-generated data, such as patient experience surveys,3 patient-reported incidents4 and healthcare complaints,5 are widely used to obtain patient-centred insights on healthcare quality and safety. The neglect of compliment letters is symptomatic of a tendency in healthcare research to focus on what goes wrong rather than what goes right.6 But, understanding how things go right is crucial to creating a resilient healthcare system.7 Compliment letters, we suggest, simultaneously provide insight into patients’ understanding of high-quality healthcare and also patients’ attempts to encourage good care.

It is widely agreed that patients should be involved in improving the quality and safety of healthcare (eg, due to unique insights, to ensure legitimacy).8 However, implementation often focuses on patient involvement in decision-making about their own care, and it remains unclear how to involve patients in broader issues such as improving services.9 Moreover, patient and public involvement in healthcare is generally service initiated,1 for example, by soliciting involvement from patient groups. A distinctive value of compliment letters is that they are patient initiated (ie, volunteered). The patients sending such letters are a self-selected group who expend considerable energy to do something; but exactly what they are attempting to do remains unclear.

The little research that has examined letters of compliment has tended to assume that compliments indicate patient satisfaction, juxtaposing them against healthcare complaints.10 11 But, there are important differences between complaints and compliments. Patients write complaints to communicate information that an institution is perceived to not possess, or to be ignoring, in order to correct an ongoing problem, prevent its recurrence or receive redress.12 By contrast, a compliment is an expression of gratitude that, according to psychological research, consists of acknowledging a good deed, rewarding it and promoting its future occurrence.13 Gratitude is elicited by feelings of thankfulness that emerge when people experience behaviours that are voluntary, beneficial to them and have a cost to the benefactor.14 Such voluntary acts are an essential feature of compliments because, according to the gratitude literature, they reveal people’s motivations.15

We conceptualise compliment letters as potentially making two contributions to improving healthcare. First, they can reveal patient perspectives on high-quality healthcare. While most safety research focuses on errors (safety I), safety itself is a dynamic non-event16 that occurs in the routine successes of everyday work (safety II) and thus is often overlooked.17 Compliment letters may further the goal of understanding high-quality and resilient healthcare7 by providing distinctive data on the everyday adaptations that, from a patient perspective, make care effective and thus underpin safety II.

Second, compliment letters can be analysed as expressions of gratitude whereby patients, unprompted and without incentive, attempt to acknowledge, reward and promote their priorities for high-quality healthcare. In effect, patients are encouraging and supporting the healthcare practices they most value (eg, rewarding the kindness of front-line staff, promoting patients’ priorities to hospital executives). Patient and public involvement in healthcare refers to the potential role of patients and the public in influencing decision-making about their own care, and about broader healthcare practices and priorities.9 18 Compliment letters may be an unrecognised resource that could be harnessed to increase patient and public involvement.19

The following analysis reports on a national sample of compliment letters submitted to English hospitals. Our aims were to: identify the practices being complimented in terms of clinical, relationship and management issues, with a focus on extra-role (ie, voluntary) behaviours in these domains; identify the gratitude aims in terms of acknowledging, rewarding and promoting practices; and test whether compliment authors have different aims with respect to recipient groups (front-line staff, patient experience teams and senior management).

Method

Methodological approach

Our methodological approach was a retrospective analysis of compliment letters. The analysis entailed theoretically motivated systematic coding of the text of the compliments according to predefined categorisations20 based on the literature on compliments, complaints and gratitude.

To identify the practices being complimented, we followed previous research11 and adapted a taxonomy for analysing healthcare complaints.21 As with previous research, we expected the compliments to cover similar domains to complaints (ie, clinical care, relationships, management), but to focus more on relationship issues.10 11 Based on the gratitude literature, we expected a focus on behaviours described as voluntary or extra-role.14 15 Identifying the practices being complimented can shed light on a patient-centred view of high-quality healthcare (ie, safety II).

To identify compliment authors’ aims in expressing gratitude, we drew on gratitude research22 and examined the extent to which compliments acknowledged, rewarded and promoted. We operationalised these as textual classifications, with acknowledging referring to publicly stating a feeling of gratitude23; rewarding being an attempt to repay feelings of gratitude24; and promoting being an attempt to directly encourage increased engagement in the behaviours that led to the compliment.13 Our analysis examined whether patients went beyond acknowledging behaviours and to also rewarding and promote them, because this would indicate that the compliments were attempts at patient and public involvement aimed at improving services.

To test whether the practices identified and the gratitude aims were targeted towards different audiences, we analysed who the letters were addressed to (ie, front-line staff, patient experience teams, senior executives). All deliberate acts of communication have addressivity; they are oriented to (ie, tailor-made for) the intended recipients of the communication.25 26 Accordingly, identifying the intended recipient of communication can provide insight on the aim of the communication.27 For example, patients wanting to merely acknowledge behaviour might write directly to the staff concerned, while patients wanting to promote the behaviour might write to the managers and chief executive officers (CEO). If the issues raised (ie, clinical, relationship, management) and the gratitude aims (ie, acknowledging, rewarding, promoting) varied according to the addressee, it would provide further evidence that the written compliments were attempts at patient and public involvement, targeted at different audiences to achieve different effects.

Data collection

We sent Freedom of Information requests to 98 randomly selected National Health Service (NHS) trusts with acute hospitals, requesting the first 26 typed/digital letters of compliment they received after a randomly generated date between April 2011 and March 2012. Data were collected between November 2015 and July 2016. The rationale for avoiding recent compliments was to ensure that only letters substantial enough to be stored were included. ‘Thank you’ cards were excluded; the letters had to contain substantive content on healthcare practices. Our request was limited to 26 letters of compliment per trust because trusts advised us that this was a reasonable request under the Freedom of Information legislation. The rationale for requesting data from 98 trusts was to ensure that we hit a target of 1045 compliments with a 50% response rate—the target required for us to predict population means with a CI of 3% (with 95% confidence).

Seventy-three NHS trusts responded, and 54 provided redacted written compliments. The teams responsible for the compliments included the complaints department, patient experience teams and the chief executives’ office. Eleven trusts did not maintain a log of compliments (‘there is no requirement’), five only maintained a log of the number of compliments (‘once logged, the letters, cards or emails are destroyed’) and three declined to provide compliments. We received 1299 compliments, but 32 were excluded because they were handwritten (not typed). Accordingly, the final sample was 1267 compliments from 54 NHS acute trusts in England.

To obtain an estimate of the population of compliment letters, we asked 105 of 251 English NHS trusts about the number of compliments received in 2017. Forty-eight trusts reported a mean number of 299 (SD=210.3) compliment letters (ie, excluding compliments received by phone, face to face or via social media). Based on this information, we estimated there to be 52 710 formal letters of compliment submitted to English NHS trusts in 2017. Assuming the number of compliment letters received is relatively stable, this implies our sample was about 2% of the compliment letters received by English NHS trusts in 2011–2012.

Coding the compliment letters

Three classification schemes were developed to extract (1) descriptives, (2) complimented practices, and (3) gratitude aims. Each classification scheme was iteratively developed to identify textual classifications that addressed our research aims and were tractable in the textual data (ie, face validity, inter-rater reliability). The final classification schemes are available in online supplementary file 1.

bmjqs-2019-010077supp001.pdf (140.7KB, pdf)

Descriptives

The following descriptives were extracted: format (eg, paper, digital), addressee (eg, front-line staff, senior executive), author (eg, patient, family member), patient (eg, adult, child), type of care sought (eg, accident and emergency, planned procedure) and outcome (eg, positive, death).

Complimented practices

We used the Healthcare Complaints Analysis Tool’s (HCAT)21 hierarchical typology of seven problems nested within three domains: clinical (quality, safety), relationship (listening, communication, respect, rights) and management (environment, institutional processes). HCAT is a widely used reliable and valid tool for analysing complaints.28–31 Iterative testing with this typology led to two modifications. First, when patients referred to practices exceeding their expectations within any domain, this was classified as ‘extra’. Second, some compliments were too vague to fully classify; thus, we also added a ‘vague’ category within each domain.

Gratitude aims

Acknowledgement was classified in terms of: ‘thank you’, defined as expressions of thanks directed to the addressee (ie, ‘thank you’, ‘many thanks’, ‘grateful to you’); and ‘I/we thank them’, defined as expressions of thanks directed to a third party (ie, ‘I thank them’, ‘we thank them’, ‘we are grateful to them’). Rewarding was classified in terms of: ‘please thank them’, defined as requests for the addressee to personally thank a third party (ie, ‘please thank them’, ‘convey our gratitude’, ‘pass on my thanks’); ‘someone cc’d’, defined as an important third party (ie, manager, CEO, government minister, newspaper), being sent a copy of the compliment; and ‘gifts’ (ie, money, flowers, chocolates). Promoting was classified in terms of: ‘commending behaviour’, defined as commending specific behaviours as desirable; ‘NHS future’, defined as comments about the NHS, its future and what it ‘should’ be; ‘suggestions’, defined as suggestions for improvement.

Each compliment was coded once for each of the descriptive classifications (ie, each letter had to have exactly one addressee). However, each compliment letter could be classified more than once for each of the classifications of complimented behaviours and gratitude aims (ie, a letter could be classified as both acknowledging and promoting). The three classification schemes were applied to all the compliments by a trained master’s level psychology graduate. The lead author analysed 130 (10.26%) compliments to assess inter-rater reliability. Cohen’s kappa (unweighted, two coders) was calculated for each category (present vs not present). The guidelines used to interpret the kappa values were: 0–0.2 none, 0.21–0.39 minimal, 0.4–0.59 weak, 0.6–0.79 moderate, 0.8–0.9 strong and above 0.9 almost perfect.32 All variables had moderate to strong reliability, except for negative outcomes (0.393), unclear outcomes (0.289) and listening (0.325).

Data analysis

To identify the practices being complimented, we analysed the proportion of clinical, relationship or management practices reported. To identify the gratitude aims, we analysed the proportion of compliments that included an attempt to acknowledge, reward or promote complimented practices. Finally, to test the aims of compliment letters, we analysed whether the practices complimented and gratitude aims varied by addressee, using χ2 tests of independence for the presence/absence of each category cross-tabulated with addressee.

The statistical analyses were conducted using R V.3.5.1 (2018).33 Custom bar plots were created using ggplot2 V.3.1.0 (2018),34 with bar shading based on the Pearson residuals from the separate χ2 tests indicating more (residuals greater than 2 shaded dark grey) or less (residuals less than minus 2 shaded light grey) than expected (ie, residuals between 2 and minus 2 shaded medium grey). The numeric data are in online supplementary file 2 and the R script is in online supplementary file 3.

bmjqs-2019-010077supp002.xlsx (232.7KB, xlsx)

bmjqs-2019-010077supp003.pdf (137.2KB, pdf)

Results

The 1267 compliments contained 288 563 words. The mean letter length was 227.8 words (SD=157.9, range=12–1477). The majority of letters were submitted on paper (80%, n=1016) with the remaining sent digitally via email. Descriptive details are reported in table 1. All percentages pertain to the entire sample of compliments (except in figures 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Descriptive details of the compliment letters

| Letter details | % | n |

| Format | ||

| Paper letter | 80 | 1016 |

| Digital letter | 20 | 251 |

| Addressee | ||

| Front-line staff | 17 | 210 |

| Team/unit/department | 53 | 667 |

| Senior management | 31 | 390 |

| Author | ||

| Patient | 58 | 731 |

| Family or friend | 36 | 459 |

| Other (eg, staff, GP, private carer) | 6 | 77 |

| Patient age | ||

| Child | 7 | 86 |

| Adult (not described as elderly) | 60 | 754 |

| Elderly | 20 | 248 |

| Unclear | 14 | 179 |

| Type of care sought | ||

| Accident and emergency | 31 | 388 |

| Planned procedure | 27 | 346 |

| Chronic care | 24 | 308 |

| Maternity | 4 | 52 |

| Unclear | 14 | 173 |

| Outcome | ||

| Positive | 32 | 407 |

| Expected | 54 | 689 |

| Negative | 2 | 26 |

| Patient death | 11 | 135 |

| Indeterminate | 1 | 10 |

GP, general practitioner.

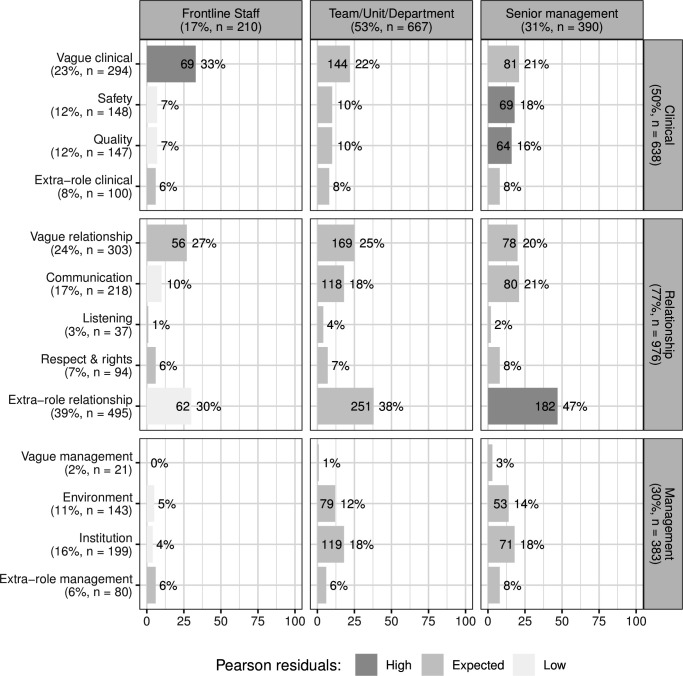

Figure 1.

Frequency of clinical, relationship and management practices complimented cross-tabulated with addressees. Shading indicates whether Pearson residuals from separate χ2 tests, performed along each row, were more (dark grey) or less (light grey) than expected. The numeric annotations refer to the total number of compliments and the percentage of compliments for the given addressee.

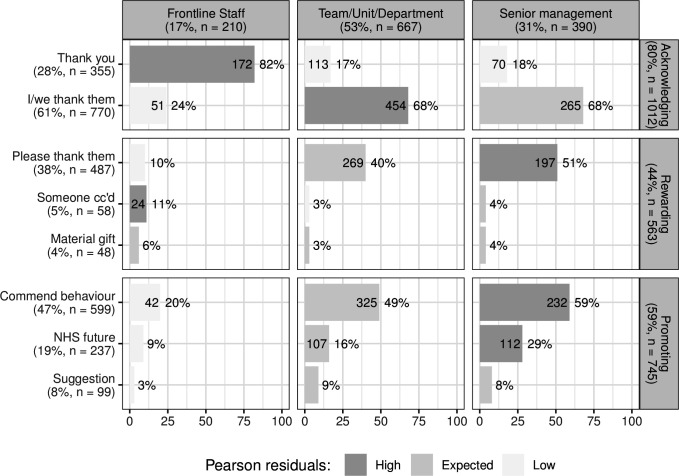

Figure 2.

Frequency of acknowledging, rewarding and promoting cross-tabulated with addressees. Shading indicates whether Pearson residuals from separate χ2 tests, performed along each row, were more (dark grey) or less (light grey) than expected. The numeric annotations refer to the total number of compliments and the percentage of compliments for the given addressee. NHS, National Health Service.

Complimented practices

Relationship (77%, n=976), clinical (50%, n=638) and management (30%, n=383) practices were complimented.

Relationship

Twenty-four per cent (n=303) of compliments reported vague relationship practices, such as describing staff as ‘caring’, ‘compassionate’, ‘kind’, ‘patient’, ‘sympathetic’ and ‘empathetic’. Three per cent (n=37) mentioned listening (eg, staff acknowledging information from patients). Seventeen per cent (n=218) mentioned communication (eg, patients were kept informed). Seven per cent (n=94) mentioned respect and rights, especially staff treating patients with dignity (eg, providing privacy). The most common relationship practice was extra-role behaviour (39%, n=495). Compliment authors stated that staff went ‘the extra mile’, ‘took extra time’, ‘went out of their way’ or ‘did everything they could’ to establish rapport, provide emotional security and quell anxieties. A common theme was small gestures by staff that were taken to reveal a caring attitude: ‘The following morning when she started work, she came onto the ward to see me and check I was OK even though she wasn’t looking after me that day and came to say goodbye when I was discharged!’

Clinical

Twenty-three per cent (n=294) of compliments provided vague references to clinical practices (eg, ‘great treatment’, ‘clinical capability’, ‘professionalism’, ‘technical ability’). Twelve per cent (n=148) mentioned good safety, such as making accurate diagnoses, prescribing appropriate medication and responding promptly to emergencies. Twelve per cent (n=147) mentioned good quality, specifically, monitoring, following care plans and hygiene procedures. Eight per cent (n=100) reported extra-role clinical practices (eg, time, skill, effort, care) that exceeded expectations. For example, staff ‘going the extra mile’ by staying late to ensure the accuracy of a test, conducting extra tests or tailoring care plans.

Management

Two per cent (n=21) of compliments reported vague management practices, such as the unit being ‘well organised’ and operating ‘efficiently’. Eleven per cent (n=143) mentioned the environment, such as the ‘brightness’ of the accommodation, having a TV or good food. Sixteen per cent (n=199) mentioned institutional processes, such as short waiting times, efficient handling of patient records, ease of booking appointments, service integration and successful complaint investigations. Six per cent (n=80) reported extra-role management issues, such as the ‘exceptional leadership’ of managers, and providing extra services deemed to be non-core or vulnerable to budget cuts (eg, services for counselling and autism). Compliments also mentioned the importance of extra courses and training for patients, social events and opportunities to socialise with other service users and staff.

Gratitude aims

The gratitude aims of acknowledging (80%, n=1012), rewarding (44%, n=563) and promoting (59%, n=745) were evident.

Acknowledging

‘Thank you’ aims were evident in 28% (n=355) of compliments. These cases were often precipitated by patient recovery, returning to work or moving to another service. Staff also received ‘thank you’ messages for positive outcomes and often from patients recovering from an accident. These messages tended to be short and mark a successful conclusion to the care episode. ‘I felt I couldn’t let another day go by without writing to thank you […] to tell you the massive difference you made to my life.’ A notable variant of the ‘thank you’ messages concerned patient death. These compliments tended to emphasise dignity, care and pain management, and provide closure to intense interaction with clinical staff. ‘I/we thank them’ aims were evident in 61% (n=770) of compliments, with gratitude often directed at ‘all staff’. After 2 years of treatment, one patient wrote: ‘My thanks also extend not only to doctors, consultants and nurses but to receptionists, cleaners, catering staff and in fact all those people who in various ways make one’s stay more tolerable.’

Rewarding

The most common reward was social recognition. ‘Please thank them’ aims were evident in 38% (n=487) of compliments. Reward also involved ensuring social recognition, for example, by cc’ing the CEO (5%, n=58). Material gifts were infrequently mentioned in the letters (4%, n=48) and most were monetary (other gifts were flowers, chocolates and wine). Monetary gifts were never intended for individuals and were most frequently earmarked for equipment or staff training. One family ‘decided that all monies collected after [a patient’s] funeral should be donated to a staff fund to go towards nursing training’.

Promoting

The most common type of promoting was commending specific practices (47%, n=599). Commendations often named specific members of staff, and the behaviours commended were broad and covered clinical (‘the audiologist quickly identified the issue’, ‘difficult manoeuvre with great speed and skill’), relationship (‘made her laugh’, ‘listened carefully’) and management (‘team leadership’, ‘greeted promptly by reception’) aspects. The NHS’s future was regularly mentioned (19%, n=237), usually in the context of reduced funding and public debate about the NHS. One patient wrote: ‘If ever there was a reason to keep the NHS going, then this is it.’ Suggestions for improvement were common (8%, n=99), and were often based on problems experienced (ie, admissions system, appointments, hygiene, staff time, equipment) during otherwise excellent treatment.

Addressees

The compliments were addressed to teams/units/departments (53%, n=667), senior management (31%, n=390) and front-line staff (17%, n=210).

Addressee and complimented practices

As shown in figure 1, front-line staff were most likely to receive compliments about vague clinical issues (p<0.01; χ2), positive outcomes (p<0.01; χ2) and death (p<0.01; χ2). Analysis of the letters suggests that these patterns reflected patients’ assumptions that staff understood the specifics of their case (‘as you know’), wishing to share good outcomes (‘thought you would like to know’), and the close emotional relationships formed during tragic cases in which patients wanted staff to know that the family did not assign any blame (‘nothing else you could have done’). Front-line staff tended not to receive compliments about environment (p<0.01; χ2) or institutional issues (p<0.01; χ2), indicating that assumed responsibility for this lies elsewhere. Senior management were most likely to receive letters about safety (p<0.01; χ2), quality of care (p<0.01; χ2) and extra-role relationship behaviours. This suggests that the compliment authors want management to ensure extra-role behaviours are valued.

Addressee and gratitude aims

As shown in figure 2, acknowledgements (ie, ‘thank you’) were more likely to be sent to front-line staff (p<0.01; χ2), often related to chronic conditions where a long-term relationship developed. For rewarding, senior management received proportionally more messages requesting staff to be thanked (p<0.01; χ2), with over half of their letters making this request. These ranged from general statements such as ‘pass on my thanks’ to more specific requests with staff names and details, asking addressees to ‘ensure’ recognition. Reward through social recognition (ie, cc’ing the CEO) was most common for front-line staff (p<0.01; χ2). In terms of promoting behaviours, senior management received far more such letters, whereas front-line staff received the fewest (p<0.01; χ2). The NHS’s future was mentioned in 19% (n=237) of compliments, and senior management received more of these letters (p<0.01; χ2). Front-line staff received the fewest suggestions for improvements (p<0.01; χ2). Thus, senior management received compliments targeted at more system-level changes and priorities.

Discussion

The letters of compliment describe high-quality healthcare from the patients’ point of view. They emphasise personal relationships with individual members of staff and, to a lesser extent, clinical safety. The letters focusing on personal relationships were sent either to the members of staff concerned or their superiors. The letters focusing on clinical safety were most likely to be sent to senior managers. Extra-role behaviours (the hallmark of gratitude) were frequently reported (eg, staff staying late, checking up on patients, conducting extra tests, hosting social events). Such voluntary acts are particularly revealing about motivation.14 15 Perhaps patients, unsure about staff competence, use these voluntary acts to assess staff motivation and thus the potential quality of care.35

Research on safety has shown that staff skills and staff motivation are important for safe and resilient healthcare.36 Safety II depends on staff not merely following procedures and plans.17 There is invariably a mismatch (although usually small) between what has been planned for (based on the past) and what actually happens (the future).17 Underspecified and often discretionary staff action bridges the plans made at time 1 and the unexpected events of time 2, thus underpinning safety II. The compliment letters reveal that such extra-role behaviours are widespread, and highly valued by patients.

The letters of compliment also aimed to encourage high-quality healthcare. The letters addressed to front-line staff attempted to acknowledge exceptional practice and caring relationships. The letters addressed to senior management were often aimed at giving social recognition to front-line staff and encouraging senior management to publicly recognise extra-role behaviour. This finding reconceptualises healthcare compliments, beyond providing information,2 10 11 as patient-initiated interventions. This is important due to the rising rates of burnout among clinical staff37 and the association between burnout and poor patient safety.38 Research has shown that patient gratitude, when it is fed back to staff, can increase staff motivation22 and reduce burnout.39 Accordingly, letters of compliment that give staff social recognition, thereby bolstering motivation, may provide a route to increasing the resilience of healthcare systems.

Patient feedback data, despite vast amounts of data collection, have arguably had little impact on improving services.40 41 Barriers include patient feedback lacking legitimacy,42 organisational inertia,41 unclear pathways,43 defensiveness to critical feedback40 and lack of established procedures for analysing unstructured textual feedback.1 Patient and public involvement is more likely to have an impact if it is credible, specific and contains narrative accounts of actual events.44 Compliments are credible, specific and narrative, and positive, which might make them a relatively effective route to improve quality.

Implications

The gratitude aims of compliment letters, especially providing social recognition, require organisational support to be achieved. In the context of debates about how to involve patients in broader healthcare delivery,9 19 effective use of compliments can provide a simple, cost-effective and respectful route to increase the breadth and depth of patients’ involvement in healthcare. The letters can involve patients in motivating staff and inform decisions at both the individual (eg, revalidation and appraisal processes)44 and organisational (eg, senior management taking account of the priorities being promoted) levels.

Enabling compliments to fulfil their stated aims can improve patient and staff well-being. Interdependence combined with gratitude is the basis of human flourishing, whereby a sense of self arises through becoming aware of interdependence with others.45 Both receiving and expressing gratitude has been found to improve well-being.46 Thus, when compliments are analysed systematically and used to close the feedback loop between staff and patients (eg, CEOs passing on gratitude), they can strengthen the community of practice leading to ‘proactive relationships’.18

Although healthcare organisations could make better use of written compliments, we caution local managers and regulators against using them to monitor performance. Such use could lead to gaming (eg, eliciting compliments)47 or shape behaviour in unexpected ways.48 Instead of using compliment counts as a metric, local managers and regulators should ensure that staff have sufficient degrees of freedom for extra-role behaviour; and support the stated aims of compliments by passing on and acting on the information contained.

Limitations

The sample of written compliments comes from England’s acute NHS trusts. Future research is needed to determine the comparability to other NHS organisations (community care, mental health and primary care) and other national contexts. Despite anyone being free to submit a written compliment, it is not known how representative compliment authors are of the wider patient population. Patients are increasingly using digital channels of feedback that constitute a different, and possibly more asymmetrical,49 relationship to staff. Although compliments consistently emphasise relationship issues within healthcare,11 this should not be interpreted as minimising other issues. Patients might focus on relationship issues because they believe that the other aspects of the service are either adequate or outside their competence, or that communicating such priorities should be targeted elsewhere (ie, CEO).

Caution is required when valorising extra-role behaviours. High levels of extra-role behaviour can indicate organisational problems, with staff having to ‘go the extra mile’ to compensate for institutional failings (ie, staff shortages). Even when healthcare staff feel unsupported, they maintain efforts towards immediate patient care because of strong professional values.50 Therefore, complimented, yet unrewarded, acts (ie, staying late) might mask inadequate resources51 and even perpetuate such exploited labour.52

Conclusion

Despite an absence of organisational support, or even dedicated email addresses, thousands of patients submit lengthy letters of gratitude to hospitals with no ostensible benefit to themselves. These patients often mention extra-role behaviours that indicate motivated and caring staff. But, these letters are themselves extra-role behaviours: they are unsolicited reciprocations aimed at recognising and motivating staff and thus improving healthcare. In short, written compliments identify and attempt to encourage a patient-centric vision for high-quality healthcare.

Footnotes

Contributors: AG produced the initial analysis and draft manuscript. TWR aided in the analysis and the write-up. The research design and conceptualisation was shared.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

All numeric data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. The coding schemes, numeric data and analysis scripts are available in the supplementary files.

References

- 1. Marsh C, Peacock R, Sheard L, et al. Patient experience feedback in UK hospitals: what types are available and what are their potential roles in quality improvement (Qi)? Health Expect 2019;22:317–26. 10.1111/hex.12885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ashton S. Using compliments to measure quality. Nurs Times 2011;107:14–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Flott KM, Graham C, Darzi A, et al. Can we use patient-reported feedback to drive change? the challenges of using patient-reported feedback and how they might be addressed. BMJ Qual Saf 2017;26:502–7. 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-005223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ward JK, Armitage G. Can patients report patient safety incidents in a hospital setting? A systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:685–99. 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reader TW, Gillespie A, Roberts J. Patient complaints in healthcare systems: a systematic review and coding taxonomy. BMJ Qual Saf 2014;23:678–89. 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. O'Hara JK, Lawton RJ. At a crossroads? key challenges and future opportunities for patient involvement in patient safety. BMJ Qual Saf 2016;25:565–8. 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-005476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Braithwaite J, Wears RL, Hollnagel E. Resilient health care: turning patient safety on its head. Int J Qual Health Care 2015;27:418–20. 10.1093/intqhc/mzv063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vincent CA, Coulter A. Patient safety: what about the patient? Qual Saf Health Care 2002;11:76–80. 10.1136/qhc.11.1.76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ocloo J, Matthews R. From tokenism to empowerment: progressing patient and public involvement in healthcare improvement. BMJ Qual Saf 2016;25:626–32. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burstein J, Fleisher GR. Complaints and compliments in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 1991;7:138–40. 10.1097/00006565-199106000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mattarozzi K, Sfrisi F, Caniglia F, et al. What patients' complaints and praise tell the health practitioner: implications for health care quality. A qualitative research study. Int J Qual Health Care 2017;29:83–9. 10.1093/intqhc/mzw139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gillespie A, Reader TW. Patient-Centered insights: using health care complaints to reveal hot spots and blind spots in quality and safety. Milbank Q 2018;96:530–67. 10.1111/1468-0009.12338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McCullough ME, Kilpatrick SD, Emmons RA, et al. Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychol Bull 2001;127:249–66. 10.1037/0033-2909.127.2.249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McCullough ME, Tsang J. Parent of the virtues? The prosocial contours of gratitude. : Emmons RA, McCullough ME, . The psychology of gratitude. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2004: 123–41. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Heider F. The psychology of interpersonal relations. London, UK: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weick KE. Organizational culture as a source of high reliability. Calif Manage Rev 1987;29:112–27. 10.2307/41165243 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hollnagel E. Safety-I and safety-II: the past and future of safety management. Surry, UK: Ashgate Publishing, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lalani M, Baines R, Bryce M, et al. Patient and public involvement in medical performance processes: a systematic review. Health Expect 2019;22:149–61. 10.1111/hex.12852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Coulter A, Ellins J. Patient-Focused interventions: a review of the evidence. London, UK: Health Foundation London, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Krippendorff K. Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. 4th. London, UK: SAGE Publications, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gillespie A, Reader TW. The healthcare complaints analysis tool: development and reliability testing of a method for service monitoring and organisational learning. BMJ Qual Saf 2016;25:937–46. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aparicio M, Centeno C, Robinson C, et al. Gratitude between patients and their families and health professionals: a scoping review. J Nurs Manag 2019;27:286–300. 10.1111/jonm.12670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Steindl-Rast D. Gratitude as thankfulness and as gratefulness. : The psychology of gratitude. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2004: 282–9. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Peterson BE, Stewart AJ. Antecedents and contexts of generativity motivation at midlife. Psychol Aging 1996;11:21–33. 10.1037/0882-7974.11.1.21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bakhtin M. Speech genres & other late essays. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Linell P. Rethinking language, mind, and world dialogically: Interactional and contetxtual theories of human sense-making. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gillespie A, Cornish F. Sensitizing questions: a method to facilitate analyzing the meaning of an utterance. Integr Psychol Behav Sci 2014;48:435–52. 10.1007/s12124-014-9265-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jerng J-S, Huang S-F, Yu H-Y, et al. Comparison of complaints to the intensive care units and those to the general wards: an analysis using the healthcare complaint analysis tool in an academic medical center in Taiwan. Crit Care 2018;22:335. 10.1186/s13054-018-2271-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mack JW, Jacobson J, Frank D, et al. Evaluation of patient and family outpatient complaints as a strategy to prioritize efforts to improve cancer care delivery. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2017;43:498–507. 10.1016/j.jcjq.2017.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Trbovich P, Vincent C. From incident reporting to the analysis of the patient journey. BMJ Qual Saf 2019;28:169–71. 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wallace E, Cronin S, Murphy N, et al. Characterising patient complaints in out-of-hours general practice: a retrospective cohort study in Ireland. Br J Gen Pract 2018;68:e860–8. 10.3399/bjgp18X699965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med 2012;22:276–82. 10.11613/BM.2012.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2017. https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. London, UK: Springer, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Reader TW, Gillespie A. Patient neglect in healthcare institutions: a systematic review and conceptual model. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:156. 10.1186/1472-6963-13-156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Griffin MA, Neal A. Perceptions of safety at work: a framework for linking safety climate to safety performance, knowledge, and motivation. J Occup Health Psychol 2000;5:347–58. 10.1037/1076-8998.5.3.347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Protection M. Breaking the burnout cycle: keeping doctors and patients safe. London: Medical Protection Society, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hall LH, Johnson J, Watt I, et al. Healthcare staff wellbeing, burnout, and patient safety: a systematic review. PLoS One 2016;11:e0159015. 10.1371/journal.pone.0159015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Converso D, Loera B, Viotti S, et al. Do positive relations with patients play a protective role for healthcare employees? effects of patients' gratitude and support on nurses' burnout. Front Psychol 2015;6:470. 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liu JJ, Rotteau L, Bell CM, et al. Putting out fires: a qualitative study exploring the use of patient complaints to drive improvement at three academic hospitals. BMJ Qual Saf 2019;28:894–900. 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sheard L, Peacock R, Marsh C, et al. What's the problem with patient experience feedback? A macro and micro understanding, based on findings from a three-site UK qualitative study. Health Expect 2019;22:46–53. 10.1111/hex.12829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sheard L, Marsh C, O'Hara J, et al. The Patient Feedback Response Framework - Understanding why UK hospital staff find it difficult to make improvements based on patient feedback: A qualitative study. Soc Sci Med 2017;178:19–27. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. van Dael J, Reader TW, Gillespie A, et al. Learning from complaints in healthcare: a realist review of academic literature, policy evidence and front-line insights. BMJ Qual Saf 2020;29:684–95. 10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Baines R, Regan de Bere S, Stevens S, et al. The impact of patient feedback on the medical performance of qualified doctors: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ 2018;18:173. 10.1186/s12909-018-1277-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mead GH. Mind, self & society from the standpoint of a social behaviorist. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pressman SD, Kraft TL, Cross MP. It’s good to do good and receive good: The impact of a ‘pay it forward’ style kindness intervention on giver and receiver well-being. J Posit Psychol 2015;10:293–302. 10.1080/17439760.2014.965269 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bevan G. Changing paradigms of governance and regulation of quality of healthcare in England. Health Risk Soc 2008;10:85–101. 10.1080/13698570701782494 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48. McGivern G, Fischer MD. Reactivity and reactions to regulatory transparency in medicine, psychotherapy and counselling. Soc Sci Med 2012;74:289–96. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.09.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Locock L, Skea Z, Alexander G, et al. Anonymity, veracity and power in online patient feedback: A quantitative and qualitative analysis of staff responses to patient comments on the 'Care Opinion' platform in Scotland. Digit Health 2020;6:2055207619899520:205520761989952. 10.1177/2055207619899520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hyde P, Harris C, Boaden R, et al. Human relations management, expectations and healthcare: a qualitative study. Human Relations 2009;62:701–25. 10.1177/0018726709103455 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Aronson J, Neysmith SM. “You’re not just in there to do the work”: depersonalizing policies and the exploitation of home care workers’ labor. Gend Soc 1996;10:59–77. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wood AM, Emmons RA, Algoe SB, et al. A dark side of gratitude? Distinguishing between beneficial gratitude and its harmful impostors for the positive clinical psychology of gratitude and well-being. : Wood AM, Johnson J, . The Wiley Handbook of positive clinical psychology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2016: 137–51. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjqs-2019-010077supp001.pdf (140.7KB, pdf)

bmjqs-2019-010077supp002.xlsx (232.7KB, xlsx)

bmjqs-2019-010077supp003.pdf (137.2KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All numeric data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. The coding schemes, numeric data and analysis scripts are available in the supplementary files.