Abstract

Objective:

How the introduction of new pharmaceuticals affects spending for treatment of children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is unknown. This study examined trends in use of pharmaceuticals and their costs among children with ADHD from 1996 to 2005.

Methods:

This observational study used annual cohorts of children ages three to 17 with ADHD (N=107,486 unique individuals during the study period) from Florida Medicaid claims to examine ten-year trends in the predicted probability for medication use for children with ADHD with and without psychiatric comorbidities as well as mental health spending and its components. Additional outcome measures included average price per day and average number of days filled for medication classes.

Results:

Overall, the percentage of children with ADHD treated with ADHD drugs increased from 60% to 63%, and the percentage taking antipsychotics more than doubled, from 8% to 18%. In contrast, rates of antidepressant use declined from 21% to 15%, and alpha agonist use was constant, at 15%. Mental health spending increased 61%, with pharmaceutical spending representing the fastest-rising component (up 192%). Stimulant spending increased 157%, mostly because of increases in price per prescription. Antipsychotic spending increased 588% because of increases in both price and quantity (number of days used). By 2005, long-acting ADHD drugs accounted for over 90% of stimulant spending.

Conclusions:

Long-acting ADHD drugs have rapidly replaced short-acting stimulant use among children with ADHD. The use of antipsychotics as a second-tier agent in treating ADHD has overtaken traditional agents such as antidepressants or alpha agonists, suggesting a need for research into the efficacy and side effects of second-generation antipsychotics among children with ADHD.

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most prevalent childhood mental disorders in the United States. Between 6% and 8% of children will have ADHD at some point (1–4), and the costs of treating it are comparable with other chronic childhood conditions, such as asthma (5,6).

Stimulant treatment for ADHD is well established and has proven superior to behavioral treatment for the core symptoms of ADHD; however, both have been shown to improve behavior from baseline (7,8). Alpha agonists and some antidepressants are used as adjunctive or second-tier medications for ADHD when symptoms remain despite stimulant therapy (9,10). Use of other types of psychotropic medication may also be clinically indicated among children with ADHD if they have comorbid psychiatric disorders. For example, children with ADHD and depression may be treated with both stimulants and antidepressants.

In the past two decades, the psychopharmacological landscape for children has evolved. Since 1999 multiple intermediate- and long-acting stimulant formulations for methylphenidate and amphetamine salts have been approved. For methylphenidate and dexmethylphenidate, several long-acting formulations have been introduced: Metadate ER in 1999, Concerta and Methylin ER in 2000, Metadate CD in 2001, Ritalin LA in 2002, Focalin XR in 2005, and Daytrana in 2006. For the amphetamine salts and lisdexamfetamine, long-acting formulations have included Adderall XR as of 2001 and Vyvanse as of 2007. In addition, the nonstimulant atomoxetine was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of ADHD in 2002. Many of these new formulations allow once-a-day dosing, which may increase compliance and thus overall effectiveness (11,12).

The introduction of second-generation antipsychotics in 1993 was widely believed to improve the safety and decrease neurological side effects of antipsychotic use. Second-generation antipsychotics opened the door for increased off-label use in a wider population, most notably elderly people and children (13). Finally, new concerns about a possible link between suicidality and antidepressants among children and adolescents have decreased both treated depression rates as well as antidepressant treatment of newly diagnosed children (14,15).

Despite the prevalence of ADHD, the introduction of long-acting ADHD therapy, and significant changes in our pharmacological approach to children, we have little information on how pharmacological treatment patterns and spending on such treatment for children with ADHD have changed over the past decade. Past studies have shown that increasing use of psychotropic medications is particularly acute for children insured by Medicaid as opposed to private insurance (16). To our knowledge, only one study has examined trends in medication treatment past 2001 for patients with ADHD, and that study focused only on stimulant use and not on other psychotropic medications and spending (17).

In this study we used a large, state Medicaid database to quantify trends in pharmaceutical treatment and spending for children with ADHD from 1996 to 2005. We sought to answer four questions. First, how did use of ADHD drugs (that is, stimulants and atomoxetine) and other medication classes change over this decade among children with ADHD with and without psychiatric comorbidities? Second, to what extent did trends in medication spending drive increased mental health spending for children with ADHD? Third, how did changing trends in utilization and price influence medication spending by medication class? Finally, among ADHD drugs, how did patterns of spending change between short-acting and long-acting medications?

Methods

Data and cohort selection

We used administrative data (eligibility and claims files) from Florida’s Medicaid program for fiscal years (FYs) 1996–2005 (Florida’s Medicaid fiscal year runs from July 1 to June 30). Because, beginning in FY 2006, Florida moved large numbers of Medicaid enrollees into prepaid mental health plans that do not reliably report encounter data, we could not construct reliable trends past 2005. Through FY 2005, Florida’s Medicaid was primarily a fee-for-service program, had enrollment ranging from 2.1 to 2.9 million people, and was the fourth largest in the United States. The study underwent institutional review board approval.

We defined annual cohorts of children with ADHD consisting of children between the ages of three and 17 who had two or more outpatient or inpatient claims with ADHD (ICD-9 code 314) on different days during the fiscal year. The two-claim method has been used in multiple studies to define children who are actively receiving treatment (5,18,19). For other psychiatric disorders, a similar but less stringent method has been shown to have a low rate of incorrectly including a person who does not have a diagnosis (false positive) but a higher rate of excluding a person with a diagnosis (false negative) (20). This algorithm implies that our cohort was likely to have few false positives but that there may have been many children with ADHD who were not included. For these children, we cannot report on their pharmaceutical utilization or spending. To ensure accurate estimates of annual spending and utilization, we examined data only for children who had at least ten months of Medicaid coverage. Data were excluded if children were enrolled in a health maintenance organization program or prepaid behavioral health plan. We also excluded data of children with pervasive developmental disorders, mental retardation, or childhood schizophrenia or psychotic disorders because many of these children experience attentional difficulties labeled ADHD secondary to their primary intellectual impairment (21).

Measures

Demographic characteristics.

We used eligibility files from Florida Medicaid to identify children’s age, sex, race or ethnicity, and Medicaid eligibility.

Utilization and spending.

We classified claims as mental health if they met any of the following criteria: the procedure code was mental health specific, the place of service was mental health specific, a psychiatric diagnosis was present, or the provider was a mental health specialist. Claims were categorized into inpatient, outpatient, and pharmaceutical claims. Inpatient stays included hospital claims with a psychiatric primary diagnosis. Outpatient claims included medical or psychopharmacological visits, therapy visits (group and family), evaluation visits, case management services, and programs specific to mental health such as day or residential treatment. Mental health pharmaceutical claims included medications primarily used to treat psychiatric illnesses, such as antipsychotics, antidepressants, ADHD drugs (stimulants and atomoxetine), antianxiety medications, mood stabilizers, and alpha agonists.

For each category of spending, we summed the amount paid on the claims. For inpatient claims we included all claims that occurred during the period of hospitalization that were mental health specific. Using the Southern Cities medical care component of the consumer price index, we adjusted all dollar amounts to FY 2005 dollars. This approach estimated direct costs because enrollees in Florida Medicaid have no copayments.

Comorbidities.

We classified children with ADHD as having the following psychiatric comorbidities if there were claims within the fiscal year with the following disorders and ICD-9 codes: bipolar disorder (codes 296.1 and 296.4–8), externalizing disorders (conduct disorder, code 312; oppositional defiant disorder, code 313.81), depression (codes 296.2, 296.3, 311, and 300.4), adjustment disorder (code 309), and other mental health or substance use disorders (codes 290–315). In the case of multiple comorbid diagnoses, we applied a hierarchy (the order listed above) based on disease severity and treatment patterns used in other studies (13,22). For example, if a child had claims for both bipolar disorder and depression during a year, the child was classified as having bipolar disorder.

Analysis

Analyses were conducted separately within each FY for each child. We report descriptive data on the demographic trends of the population. We used a generalized estimating equation–based logistic regression clustered on the individual level to control for the effects of demographic characteristics and comorbidities to estimate the predicted probability of medication use among children with ADHD with and without psychiatric comorbidities in FYs 1996 and 1997 as well as FYs 2004 and 2005.

We report trends over ten years in mean±SE total spending, mental health spending, and mental health component spending. We calculated the percentage increase in spending after combining the first two and last two FYs to minimize the impact of year-to-year fluctuation. We present data at three time points—the first two years, the middle two years, and the last two years—to evaluate whether spending changes were roughly steady.

Given the large expansion in spending on pharmacotherapy, we described trends in mean spending as well as its components, price and quantity, by medication class. We calculated average price per day for each medication class by taking the mean of the amount paid divided by the days supplied per pharmaceutical claim for those claims without missing data (missing data accounted for less than 5% of the yearly claims). Our average price per day refers to the mix of medications purchased in each class and could go up if either the price for particular medications increased or the mix of medications shifted toward more expensive medications. We defined quantity by calculating the mean days of use per person, which was the sum of the number of days supplied by medication class. Last, we calculated the composition of spending for generic and branded short-acting ADHD drugs as well as generic and branded long-acting ADHD drugs for these periods.

Results

We identified 107,486 unique individuals with ADHD during our study period. The number of children identified with ADHD varied from 16,305 to 35,907 per year, with more identified or treated toward the end of our study period. This corresponds to an identified ADHD prevalence of 8% in FY 1996 and 10% in FY 2005. As expected, most children with ADHD were male and eligible for Medicaid via Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (Table 1). The number of Hispanic children grew rapidly over this period, reflecting more consistent identification of ethnicity within Medicaid data as well as an increase in Hispanic children in Florida during this period (from 16% to 21%–23%, according to U.S. census estimates). The percentage of children with ADHD and comorbid psychiatric disorders also grew. Particularly noteworthy is the increase in comorbid bipolar disorder and to a lesser extent other externalizing conditions. Many children had claims from both the primary care and mental health sectors; nonetheless, more children were seen in primary care alone over this ten-year period. Finally, the mix of children from different areas of the state changed in a way that reflects the stepwise implementation of Florida’s prepaid mental health plans.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of cohorts of children in Florida Medicaid with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), fiscal years (FYs) 1996–2005

| Characteristic | FYs 1996 and 1997 | FYs 2004 and 2005 | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Age group (years) | <.01 | ||||

| 3–8 | 6,810 | 40.6 | 8,800 | 32.2 | |

| 9–13 | 8,171 | 48.7 | 12,727 | 46.5 | |

| 14–17 | 1,813 | 10.8 | 5,842 | 21.3 | |

| Sex | <.01 | ||||

| Male | 13,175 | 78.4 | 19,997 | 73.1 | |

| Female | 3,619 | 21.6 | 7,372 | 26.9 | |

| Race or ethnicity | <.01 | ||||

| White | 8,412 | 50.1 | 10,962 | 40.1 | |

| Black | 5,196 | 30.9 | 6,562 | 24.0 | |

| Hispanic | 1,553 | 9.3 | 5,236 | 19.1 | |

| Other or missing | 1,633 | 9.7 | 4,609 | 16.8 | |

| Medicaid eligibility | <.01 | ||||

| AFDC or TANFa | 11,477 | 68.3 | 20,241 | 74.0 | |

| Supplemental Security Income | 5,241 | 31.2 | 7,038 | 25.7 | |

| Other | 76 | .5 | 70 | .3 | |

| Comorbid mental illnessb | |||||

| None | 11,058 | 65.8 | 14,635 | 53.5 | <.01 |

| Bipolar disorder | 369 | 2.2 | 1,834 | 6.7 | <.01 |

| Externalizing disorders | 2,409 | 14.3 | 4,379 | 16.0 | <.01 |

| Depression | 919 | 5.5 | 1,241 | 4.5 | <.01 |

| Adjustment disorder | 1,124 | 6.7 | 1,711 | 6.3 | .07 |

| Other | 915 | 5.5 | 3,569 | 13.0 | <.01 |

| ADHD treatment | <.01 | ||||

| Primary care physician only | 3,632 | 21.6 | 6,868 | 25.1 | |

| Mental health specialist only | 5,691 | 33.9 | 6,903 | 25.2 | |

| Both primary care and mental health sector | 7,093 | 42.2 | 12,773 | 46.7 | |

| District | <.01 | ||||

| 1 | 1,281 | 7.6 | 156 | .6 | |

| 2 | 1,186 | 7.1 | 2,703 | 9.9 | |

| 3 | 1,944 | 11.6 | 4,595 | 16.8 | |

| 4 | 1,955 | 11.6 | 4,630 | 16.9 | |

| 5 | 1,490 | 8.9 | 776 | 2.8 | |

| 6 | 286 | 1.7 | 472 | 1.7 | |

| 7 | 2,654 | 15.8 | 1,307 | 4.8 | |

| 8 | 1,216 | 7.2 | 1,466 | 5.4 | |

| 9 | 1,122 | 6.7 | 2,323 | 8.5 | |

| 10 | 1,117 | 6.7 | 2,496 | 9.1 | |

| 11 | 2,543 | 15.1 | 6,445 | 23.6 | |

AFDC, Aid for Families With Dependent Children; TANF, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

Hierarchical diagnostic groups are listed in descending order.

Trends in use of psychotropic medication by children with ADHD

The predicted probability that at least one prescription of ADHD drugs would be filled for a child with ADHD increased only slightly over the decade (from 60% to 63%) (Table 2). However, the predicted probability of filling at least one antipsychotic prescription approximately doubled in the overall sample (from 8% to 18%) and increased in all subsamples including children with ADHD alone (from 5% to 12%). In contrast, the predicted probability of a child’s receiving an antidepressant prescription decreased (from 21% to 15%), and an alpha agonist prescription remained constant (15% and 15%).

Table 2.

Predicted probability of use of psychotropic medication by children in Florida Medicaid with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) with and without a comorbid mental illnessa

| Medication and comorbid condition | Fiscal years 1996 and 1997 | Fiscal years 2004 and 2005 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | |

| ADHD drugs (all children with ADHD) | 60.1 | 59.9–60.2 | 62.9 | 62.7–63.0 |

| No comorbidities | 60.9 | 60.7–61.0 | 62.7 | 62.5–62.8 |

| Bipolar disorder | 57.3 | 57.1–57.4 | 65.4 | 65.3–65.5 |

| Externalizing conditions | 59.1 | 59.0–59.3 | 64.9 | 64.7–65.0 |

| Depressive disorders | 61.1 | 60.9–61.2 | 63.9 | 63.8–64.1 |

| Adjustment disorder | 58.4 | 58.3–58.6 | 59.9 | 59.8–60.0 |

| Antipsychotics (all children with ADHD) | 8.2 | 8.1–8.3 | 17.6 | 17.5–17.7 |

| No comorbidities | 5.0 | 5.0–5.0 | 12.3 | 12.2–12.3 |

| Bipolar disorder | 28.2 | 28.1–28.3 | 51.4 | 51.3–51.5 |

| Externalizing conditions | 10.6 | 10.6–10.7 | 23.1 | 23.0–23.1 |

| Depressive disorders | 11.2 | 11.1–11.2 | 20.6 | 20.5–20.7 |

| Adjustment disorder | 5.5 | 5.5–5.5 | 15.7 | 15.7–15.8 |

| Antidepressants (all children with ADHD) | 20.9 | 20.8–21.0 | 14.5 | 14.4–14.5 |

| No comorbidities | 15.5 | 15.5–15.6 | 10.5 | 10.4–10.5 |

| Bipolar disorder | 44.8 | 44.7–44.9 | 26.6 | 26.5–26.7 |

| Externalizing conditions | 25.0 | 25.0–25.1 | 18.0 | 17.9–18.0 |

| Depressive disorders | 37.0 | 36.9–37.1 | 29.9 | 29.8–30.0 |

| Adjustment disorder | 19.3 | 19.2–19.4 | 13.0 | 12.9–13.0 |

| Alpha agonists (all children with ADHD) | 15.4 | 15.4–15.5 | 14.6 | 14.6–14.7 |

| No comorbidities | 13.4 | 13.3–13.4 | 13.2 | 13.1–13.2 |

| Bipolar disorder | 25.7 | 25.6–25.8 | 19.4 | 19.3–19.5 |

| Externalizing conditions | 18.1 | 18.0–18.1 | 17.2 | 17.1–17.3 |

| Depressive disorders | 17.5 | 17.4–17.5 | 14.3 | 14.3–14.4 |

| Adjustment disorder | 14.2 | 14.1–14.2 | 12.3 | 12.3–12.4 |

Predicted probabilities are calculated based on generalized estimating equations clustered on the individual and adjusted for demographic variables, comorbidities, and geographic regions within Florida. Comorbidities are listed in hierarchical order.

Trends in medication spending for children with ADHD

The average health care costs for children with ADHD increased almost 60% over the period studied, rising from $3,258 to $5,187 (Table 3). Spending on mental health care constituted a little over 80% of total spending and increased at a similar rate over the study period. Inpatient spending and medication spending each accounted for 11% of mental health spending initially, which grew to 18% and 20%, respectively, by the end of the study period. In contrast, outpatient mental health spending fell from 77% of mental health spending to 62% during this time. Pharmaceutical spending increased more than other components—almost tripling.

Table 3.

Trends in health care spending per child with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in Florida Medicaid, fiscal years (FYs) 1996–2005a

| Cost category | FYs 1996 and 1997 | FYs 2000 and 2001 | FYs 2004 and 2005 | % change | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SE | M | SE | M | SE | ||

| Total health care | 3,257.5 | 46.7 | 3,923.2 | 52.5 | 5,186.7 | 78.4 | 59 |

| Mental health care | 2,702.1 | 40.2 | 3,153.9 | 45.3 | 4,350.9 | 73.8 | 61 |

| Inpatient | 307.9 | 25.8 | 419.5 | 28.5 | 764.4 | 49.9 | 148 |

| Outpatient | 2,093.6 | 26.2 | 2,101.9 | 26.8 | 2,708.9 | 42.3 | 29 |

| Medications | 300.7 | 4.3 | 632.5 | 8.7 | 877.5 | 11.2 | 192 |

Dollar amounts have been adjusted to the medical care component of the consumer price index of the Southern Cities from the Bureau of Labor Statistics for fiscal year 2005.

The growth in spending on ADHD drugs and antipsychotics largely accounted for the increase in pharmaceutical spending (Table 4). The increase in stimulant spending was primarily due to price increases but also reflects a 37% increase in use. Spending on antipsychotic medication increased sixfold because of large increases in both price and utilization. By FY 2004 and FY 2005, antipsychotic spending constituted 38% of psychotropic spending for children with ADHD. In contrast, spending on both antidepressants and alpha agonists remained relatively constant. Antidepressant spending peaked in FY 2003 (data not shown). The decreased spending on alpha agonists was a result of decreased price and increased use. By the end of our observation period, the average number of days that children with ADHD used antipsychotics was higher than that for antidepressants and alpha agonists (40 days versus 28 days).

Table 4.

Trends in components of spending by psychotropic medication class per child in Florida Medicaid with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), by fiscal year (FY)a

| Measure | FYs 1996 and 1997 | FYs 2000 and 2001 | FYs 2004 and 2005 | % change | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ($) | SE | M ($) | SE | M ($) | SE | ||

| All mental health medications | |||||||

| Spending | 300.7 | 4.3 | 632.5 | 8.7 | 877.5 | 11.2 | 192 |

| Price per day | 1.7 | 7.6×10−3 | 2.7 | 8.2×10−3 | 3.1 | 8.3×10−3 | 110 |

| Days of use | 196.5 | 2.8 | 252.4 | 3.0 | 259.8 | 2.6 | 32 |

| ADHD drugsb | |||||||

| Spending | 179.7 | 2.1 | 302.5 | 3.1 | 461.9 | 4.5 | 157 |

| Price per day | 1.6 | 4.8×10−3 | 2.2 | .8×10−3 | 3.1 | 5.7×10−3 | 89 |

| Days of use | 115.4 | 1.6 | 135.1 | 1.4 | 152.2 | 1.4 | 32 |

| Antipsychotics | |||||||

| Spending | 43.9 | 2.2 | 178.3 | 5.3 | 302.0 | 7.3 | 588 |

| Price per day | 3.9 | .1 | 6.9 | .1 | 7.9 | 3.3×10−2 | 102 |

| Days of use | 12.9 | .6 | 27.5 | .8 | 40.3 | .9 | 212 |

| Antidepressants | |||||||

| Spending | 44.1 | 1.3 | 86.9 | 2.0 | 48.8 | 1.5 | 11 |

| Price per day | 1.5 | 1.4×10−2 | 2.3 | 1.1×10−2 | 1.8 | 1.0×10−2 | 17 |

| Days of use | 29.9 | .9 | 38.7 | .9 | 27.5 | .7 | −8 |

| Alpha agonists | |||||||

| Spending | 12.3 | .5 | 18 | .5 | 9.6 | .3 | −22 |

| Price per day | .6 | 3.0×10−2 | .6 | 4.3×10−3 | .4 | 3.6×10−3 | −40 |

| Days of use | 26.8 | 1.2 | 32.3 | .8 | 28.1 | .7 | 5 |

| Other mental health medicationsc | |||||||

| Spending | 27.7 | 1.2 | 54.9 | 2.1 | 58.2 | 2.6 | 110 |

| Price per day | 2.0 | 2.5×10−2 | 2.9 | 2.1×10−2 | 3.8 | 3.0×10−2 | 87 |

| Days of use | 15.0 | .7 | 20.0 | .7 | 15.9 | .6 | 5 |

Dollar amounts have been adjusted to the medical care component of the consumer price index of the Southern Cities from the Bureau of Labor Statistics for fiscal year 2005.

Stimulants and atomoxetine

Anxiolytics and mood stabilizers

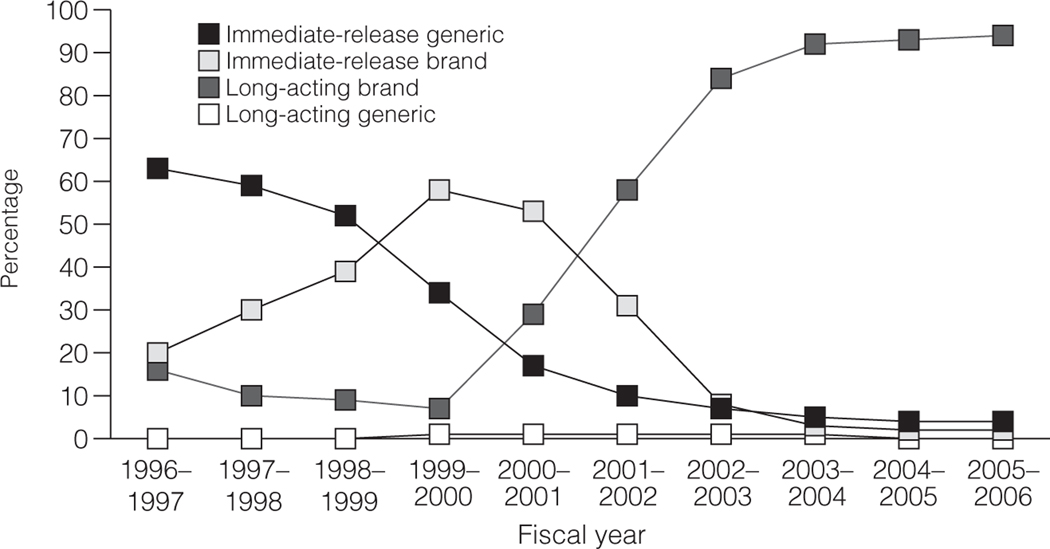

Two trends are evident from examining spending on ADHD stimulants (Figure 1). First, a temporary rise in the market share of branded, short-acting medications peaked in FY 1999 as a result of the introduction of amphetamine salts. More important, over the ten-year period, there is an almost complete shift to long-acting, brand-name ADHD drugs. By FY 2005, 94% of spending was for long-acting, brand-name ADHD drugs and 82% of ADHD drugs prescribed were long-acting, brand-name formulations.

Figure 1.

Spending on attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder medications for children, fiscal years 1996–2005a

a From Medicaid claims data. Comparisons of multiple means of amount spent for each category of stimulant medication were statistically significant at p<.01 for all fiscal years.

Discussion

Our data document substantial changes in patterns of pharmacological treatment of children with ADHD. Over a ten-year period, there was a mild increase in stimulant use (in both percentage of children treated and average number of days used), suggesting that the large increases seen in the previous decade have attenuated (23–25). In contrast, the use of antipsychotic medication by children with ADHD has rapidly expanded. This increased use was most prominent for children with both ADHD and bipolar disorder but also doubled for children with ADHD alone.

Even after correcting for inflation, we found that these new treatment patterns corresponded to an approximately 60% growth in overall health care spending and mental health care spending. Pharmaceutical spending (up 192%) was the fasting-rising component, followed by spending on inpatient care (148%). In contrast, spending on outpatient care remained roughly the same. The spending increase in inpatient care may be related to the increased severity and prevalence of comorbidities during this period, in particular the increase in bipolar disorder (26).

Spending on ADHD drugs and antipsychotics contributed most heavily toward pharmaceutical expenditure growth. Higher prices for new, long-acting ADHD drugs, as opposed to large increases in use, drove the growth in spending on ADHD stimulants. In contrast, a tripling of use as well as higher prices contributed to increased spending on antipsychotics. Multiple factors have contributed to increased pharmaceutical spending, including increased access to treatment via primary care, improved drug insurance coverage, decreased stigma, and new psychiatric medications (27). Still, these results raise two questions: are long-acting brand-name ADHD drugs worth the higher costs? And what is driving the high use of second-generation antipsychotics by children with ADHD?

The rapid uptake of long-acting ADHD drugs coincided with only a modest increase in overall use. Long-acting formulations have permitted once-a-day dosing and likely represent a significant improvement for children who are no longer required to visit a nurse during the school day. Children taking long-acting formulations stay on ADHD drugs for more days than those taking short-acting formulations and are less likely to change to short-acting formulations even if long-acting formulations require higher out-of-pocket expenses (28,29). Recent approaches to treating ADHD have encouraged the use of ADHD drugs for longer periods each day as well as into adolescence and young adulthood in order to minimize the negative academic and social consequences of ADHD. Given the benefits of once-a-day dosing, higher costs to Medicaid may be justified if such dosing consistently improves adherence and, as a result, outcomes.

The large increase in antipsychotic use reveals a tension between community prescribing patterns and the scientific evidence base. Second-generation antipsychotics have been shown in randomized, placebo-controlled trials to be effective for children with schizophrenia or other psychotic illness, bipolar disorder, Tourette’s syndrome, and behavioral disturbances because of pervasive developmental disorders, autism, or mental retardation (30–36). The use of second-generation antipsychotics to minimize aggressive behavior is common for adults; however, the evidence for adopting the same approach for children (and the geriatric population) is weak (37). Because both neurological and metabolic side effects are more substantial in a pediatric population (38,39) expansion of the off-label use of antipsychotics among children with ADHD not only drives up spending but also raises concerns about possible overtreatment. Current guidelines do not recommend using antipsychotics for ADHD and do not address the use of antipsychotics by children with ADHD and psychiatric comorbidities (9,10,40). Our study clearly shows that antipsychotic use has increased among children with ADHD alone and among children who have comorbid bipolar disorder and externalizing conditions. The development and dissemination of consensus guidelines for the appropriate use of antipsychotics by children with ADHD and its common comorbidities would help guide appropriate treatment.

Relatively few prior studies have focused on changes over time for overall patterns of drug treatment for ADHD in addition to stimulant use (17,23–25,41). Our findings regarding the attenuation of the rate of stimulant use (41), the uptake of long-acting ADHD drugs (17,42), and the increasing use of antipsychotics are consistent with prior studies (13,22,43–46). However, our study provides the most recent data available on these trends for all medication classes, including the recent surge in antipsychotic use, and describes how these trends have affected pharmaceutical spending for children with ADHD. Further, our study clearly distinguishes between the independent contributions of increased use and changes in price on escalating pharmaceutical expenditures.

Several limitations to this analysis should be noted. First, the analysis examined administrative claims data with no information about clinical outcomes or symptoms. Identification of children with ADHD and other comorbidities depends on provider recognition. Therefore, the rates reported may understate or misstate a population-based case rate. Further, by requiring two diagnoses of ADHD to be included in our cohort, the results may be biased toward cohorts with more persistent or severe presentations of ADHD, as is suggested by the high percentage of children eligible for Medicaid through Supplemental Security Income. However, because this definition was consistently applied over time, it did not introduce bias to the longitudinal comparisons. For children with multiple psychiatric diagnoses in addition to ADHD, this study imposed a diagnostic hierarchy that may mask patterns due to multidiagnostic complexity. This study used Medicaid data and results may not generalize to privately insured children. Past studies have shown that children with Medicaid have lower rates of stimulant treatment, higher rates of mental illness, and higher rates of antipsychotic use (13).

Conclusions

In summary, between 1996 and 2005, patterns of psychotropic medication use changed for children with ADHD. As a result, spending on pharmaceuticals for children with ADHD doubled, driven primarily by increased spending for ADHD drugs and antipsychotics. New, long-acting ADHD drugs were integrated rapidly into this Medicaid population, suggesting good accessibility and likely leading to modest improvements in appropriate treatment. Although the use of antipsychotics increased rapidly as well, their use by children in the absence of good efficacy and safety data emphasizes the need for increased research on their efficacy and long-term side effects for children with ADHD.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by grant R01MH081819 from the National Institute of Mental Health and by the Norlien Foundation. The authors thank Bonnie T. Zima, M.D., M.P.H., for her careful reading and comments on a draft of this article and Alison Hwong, B.A., for her research assistance.

Contributor Information

Catherine A. Fullerton, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, 180 Longwood Ave., Boston, MA 02115 Department of Psychiatry, Cambridge Health Alliance, Boston..

Arnold M. Epstein, Department of Health Policy and Management, Harvard School of Public Health Division of General Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston..

Richard G. Frank, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, 180 Longwood Ave., Boston, MA 02115

Sharon-Lise T. Normand, Department of Biostatistics, Harvard School of Public Health. Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, 180 Longwood Ave., Boston, MA 02115

Christina X. Fu, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, 180 Longwood Ave., Boston, MA 02115

Thomas G. McGuire, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, 180 Longwood Ave., Boston, MA 02115

References

- 1.Barbaresi WJ, Katusic SK, Colligan RC, et al. : How common is attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? Incidence in a population-based birth cohort in Rochester, Minn. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 156:217–224, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rowland AS, Umbach DM, Stallone L, et al. : Prevalence of medication treatment for attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder among elementary school children in Johnston County, North Carolina. American Journal of Public Health 92:231–234, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harel EH, Brown WD: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in elementary school children in Rhode Island: associated psychosocial factors and medications used. Clinical Pediatrics 42:497–503, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Prevalence of diagnosis and medication treatment for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: United States 2003. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 54:842–847, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.dosReis S, Owens PL, Puccia KB, et al. : Multimodal treatment for ADHD among youths in three Medicaid subgroups: disabled, foster care, and low income. Psychiatric Services 55:1041–1048, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leibson CL, Katusic SK, Barbaresi WJ, et al. : Use and cost of medical care for children and adolescents with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA 285: 60–66, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abikoff H, Hechtman L, Klein RG, et al. : Symptomatic improvement in children with ADHD treated with long-term methylphenidate and multimodal psychosocial treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 43:802–811, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MTA Cooperative Group: A 14-month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:1073–1086, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pliszka S AACAP Work Group on Quality Issues: Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 46:894–921, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Academy of Pediatrics, Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Committee on Quality Improvement: Clinical practice guideline: treatment of the school-aged child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 108:1033–1044, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kripalani S, Yao X, Haynes B: Interventions to enhance medication adherence in chronic medical conditions. Archives of Internal Medicine 167:540–550, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saini SD, Schoenfeld P, Kaulback K, et al. : Effect of medication dosing frequency on adherence in chronic diseases. American Journal of Managed Care 15:e22–e33, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crystal S, Olfson M, Huang C, et al. : Broadened use of atypical antipsychotics: safety, effectiveness, and policy challenges. Health Affairs 28:w770–w781, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nemeroff CB, Kaladi A, Keller MB, et al. : Impact of publicity concerning pediatric suicidality data on physician practice patterns in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 64:466–472, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Libby AM, Orton HD, Valuck RJ: Persisting decline in depression treatment after FDA warnings. Archives of General Psychiatry 66:633–639, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zito JM, Safer DJ, dosReis S, et al. : Psychotropic practice patterns for youth: a 10-year perspective. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 157:17–25, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castle L, Aubert RE, Verbrugge RR, et al. : Trends in medication treatment for ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders 10:335–342, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mandell DS, Guevara JP, Rostain AL, et al. : Medical expenditures among children with psychiatric disorders in a Medicaid population. Psychiatric Services 54:465–467, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen C-Y, Gerhard T, Winterstein AG: Determinants of initial pharmacological treatment for youths with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 19:187–195, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spettell CM, Wall TC, Allison J, et al. : Identifying physician-recognized depression from administrative data: consequences for quality management. Health Services Research 38:1081–1102, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LeFever GB, Kawson KV, Morrow AL: The extent of drug therapy for attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder among children in public schools. American Journal of Public Health 89:1359–1364, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olfson M, Crystal S, Huang C, et al. : Trends in antipsychotic drug use by very young, privately insured children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 49:13–23, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olfson M, Gameroff MJ, Marcus SC, et al. : National trends in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:1071–1077, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zito JM, Safer DJ, dosReis S, et al. : Psychotherapeutic medication patterns for youths with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 153:1257–1263, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Safer DJ, Zito JM, Fine EM: Increased methylphenidate usage for attention deficit disorder in the 1990s. Pediatrics 98:1084–1088, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blader JC, Carlson GA: Increased rates of bipolar disorder diagnoses among US child, adolescent, and adult inpatients, 1996–2004. Biological Psychiatry 62:107–114, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frank RG, Goldman HH, McGuire TG: Trends in mental health cost growth: an expanded role for management? Health Affairs 28:649, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marcus SC, Wan GJ, Kemner JE, et al. : Continuity of methylphenidate treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 159:572–578, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huskamp HA, Deverka PA, Epstein AM, et al. : Impact of 3-tier formularies on drug treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:435–441, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Owen R, Sikich L, Marcus RN, et al. : Aripiprazole in the treatment of irritability in children and adolescents with autistic disorder. Pediatrics 124:1533–1540, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Findling RL, Nyilas M, Forbes RA, et al. : Acute treatment of pediatric bipolar I disorder, manic or mixed episode, with aripiprazole: a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 70:1441–1451, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Findling RL, Robb A, Nyilas M, et al. : A multiple-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of oral aripiprazole for treatment of adolescents with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 165:1432–1441, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DelBello MP, Schwiers ML, Rosenberg HL, et al. : A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of quetiapine as adjunctive treatment for adolescent mania. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 41:1216–1223, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCracken JT, McGough J, Shah B, et al. : Risperidone in children with autism and serious behavioral problems. New England Journal of Medicine 347:314–321, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snyder R, Turgay A, Aman MG, et al. : Effects of risperidone on conduct and disruptive behavior disorders in children with subaverage IQs. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 41:1026–1036, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scahill L, Leckman JF, Schultz RT, et al. : A placebo-controlled trial of risperidone in Tourette syndrome. Neurology 60:1130–1135, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Comparative Effectiveness of First and Second Generation Antipsychotics in the Pediatric and Young Adult Populations. AHRQ Effective Health Care Program Report. Rockville, Md, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2010. Available at www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/index.cfm/search-for-guides-reviews-and-reports/?pageAction=displayTopic&topicID=147. Accessed Feb 24, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shin L, Bregman H, Frazier J, et al. : An overview of obesity in children with psychiatric disorders taking atypical antipsychotics. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 16:69–79, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patel NC, Hariparsad M, Matias-Akthar M, et al. : Body mass indexes and lipid profiles in hospitalized children and adolescents exposed to atypical antipsychotics. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 17:303–311, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Medicaid Drug Therapy Management Program for Behavioral Health (MDTMP). ADHD Medication Guidelines for Children and Adolescents Age 6–17 Years., Jan 20, 2011. Available at medicaidmentalhealth.org/Guidelines/Child.aspx

- 41.Zuvekas SH, Vitiello B, Norquist GS: Recent trends in stimulant medication use among US children. American Journal of Psychiatry 163:579–585, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scheffler RM, Hinshaw SP, Modrek S, et al. : The global market for ADHD medications. Health Affairs 26:450–457, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Olfson M, Blanco C, Liu L, et al. : National trends in the outpatient treatment of children and adolescents with antipsychotic drugs. Archives of General Psychiatry 63:679–685, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cooper WO, Hickson GB, Fuchs C, et al. : New users of antipsychotic medications among children enrolled in TennCare. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 158:753–759, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aparasu RR, Bhatara V: Patterns and determinants of antipsychotic prescribing in children and adolescents, 2003–2004. Current Medical Research and Opinion 23:49–56, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patel NC, Crismon ML, Hoagwood K, et al. : Trends in the use of typical and atypical antipsychotics in children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 44:548–556, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]